Reducing Health Disparities: A Pipeline Program to Increase Diversity and Cultural Competence.

Received: 03-Jan-2022 / Manuscript No. jcmhe-22-51609 / Editor assigned: 05-Jan-2022 / PreQC No. jcmhe-22-51609 (PQ) / Reviewed: 19-Jan-2022 / QC No. jcmhe-22-51609 / Revised: 24-Jan-2022 / Manuscript No. jcmhe-22-51609 (R) / Published Date: 31-Jan-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2168-9717.1000733

Abstract

Objective: In 2019, the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research in collaboration with the Baltimore community developed Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholars, a pipeline program focused on students underrepresented in health careers interested in HIV and/or hepatitis C health disparities. This program was established to diversify the workforce and promote cultural competence as a vehicle to decrease health and health care disparities in the United States. Pipeline programs of this nature are a major step toward achieving health equity.

Methods: Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholars seeks to achieve its aims through a multipronged approach. This includes a comprehensive, cultural humility focused curriculum that students are taught by qualified faculty and community members. The students are also paired with a mentor to complete an independent research project. Our students work with a local community partner, Sisters Together and Reaching, Inc. to get hands on experience working with local populations by providing HIV and hepatitis C testing and counseling. Additionally, the program provides health careers advising throughout the school year for students pursuing graduate or medical school.

Results: The leadership team spoke with the students at the conclusion of the program and uncovered several themes. Through community work, it was clear that cultural competency requires robust understanding of the community and barriers faced. The students also highlighted that cultural humility and empathy are critical for informed care. Consistent mentorship, beyond just the summer, was also critical for expanding diversity and cultural competence in the workforce.

Conclusion: Community engagement is crucial to developing a conceptual framework for helping students understand population level healthcare disparities. Active, long term student mentorship is of utmost importance. Although outcomes will have to continue to be measured in years to come, we believe this program can help students overcome significant barriers and achieve their goals.

Keywords

HIV; Hepatitis C; Cultural competence; Health disparities; Pipeline program; Community engagement; Mentorship

Introduction

Achieving health equity and eliminating health and healthcare disparities has been a priority for medical and public health professionals for decades. Despite efforts addressing these inequities, health and healthcare disparities remain in the United States healthcare system. According to the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, for approximately 40% of quality measures, Black and American Indians/ Alaska Natives received worse health care than White people [1]. Similarly, the Hispanic participants scored worse on one third of quality measures [1]. Defined as differential outcomes between groups, health disparities result in preventable harms to many and cost the US healthcare system $ 93 billion in excess medical care [2]. One particular area of focus is Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C (HCV), which exemplify preventable and treatable diseases that disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minority groups [3]. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents that Black/African American persons and Hispanic/Latino persons accounted for 42.1% and 21.7% of all new HIV infections in 2019, respectively, as compared to their percentages of 13% and 18.5% in the general population [4,5]. Moreover, the rate of HIV infections among Black women is 16 times that of white women in the United States [4]. The Non-Hispanic Black population also experiences disproportionately high HCV rates with prevalence twice that of non-Hispanic Whites [6].

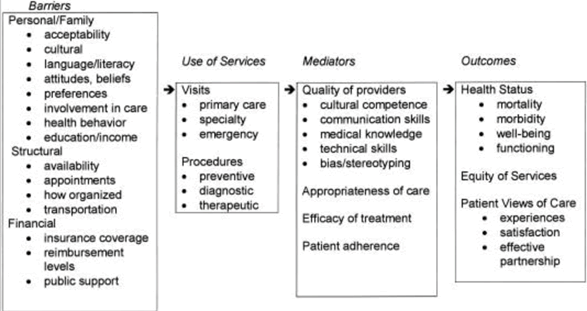

A multitude of underlying factors have been identified that contribute to health and healthcare disparities [7,8]. According to the Institute of Medicine’s model of access to health services there are personal, financial, and structural barriers that exist that prevent persons from accessing care [7]. Recent models of care highlight the importance of additionally improving quality of care as a means of reducing disparities [7]. These models show that quality of care can be improved by increasing cultural competence, addressing bias and stereotyping, and teaching communication skills [7]. Additionally, as population diversity grows within the United States, the medical field must also adapt to expand its diversity and cultural competency to meet the needs of this changing population landscape.

By 2043, it is estimated that the US will become a majority minority nation [9]. Currently, among active physicians, 56.2% identify as White, 17.1% identify as Asian, 5.8% identify as Hispanic, and 5.0% identify as Black or African American [10]. These statistics represent a stark contrast to the overall U.S. population which is 76.3% White, 5.9% Asian, 18.5% Hispanic, and 13.4% Black 5. As such, Blacks and/or African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, as well as Native Americans, Pacific islanders and mainland Puerto Ricans are considered underrepresented in medicine by the American Medical Association (AAMC), as are individuals who come from otherwise disadvantaged backgrounds [11]. The Flexner Report, published in 1910, was a major catalyst for this disparity as it resulted in five of the seven Black medical schools closing and created long lasting racial biases in medicine [12]. If the health field does not change to reflect shifting demographics, existing health disparities may stagnate or worsen.

On the provider level, having a more diverse and more culturally competent group of health care professionals can help to decrease, or even eliminate, health and healthcare disparities that widely exist across the United States. Physician patient racial concordance minimizes the presence of implicit biases and stereotyping that may exist when a provider is not culturally informed [13]. Furthermore, to help decrease health disparities, it is critical for providers of all races and ethnicities to understand the various dimensions of patient’s health including values, beliefs, and behaviors. Increased provider cultural competency may enable providers to prevent biases from altering clinical judgment while increasing patient trust, engagement, and adherence [14-16].

One means of increasing diversity with the aim of decreasing health disparities in the healthcare field are pipeline programs. These programs intend to target, enroll and support underrepresented students, specifically minority and low income, with the goal of increasing representation. These programs are a proposed solution to the lack of diversity in healthcare professions and can also promote cultural competence broadly amongst all participants. Multiple conceptual models of pipeline programs have been shown to be successful at promoting diversity in the health field [17-19]. Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparities Scholars was launched in 2019 and is a summer program for undergraduate students from across the United States interested in HIV and/or HCV health disparities and their intersection with substance use (addiction and overdose), violence, mental health, and the social determinants of health. The program aims to promote comprehensive care of individuals impacted by HIV and HCV infections, create a pipeline to health careers for diverse applicants and enhance the cultural competence of all participants. The program was launched in conjunction with Sisters Together and Reaching, Inc. (STAR), a community based organization focused on HIV and HCV outreach. This paper describes the development of Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholars and initial lessons learned.

Objectives

The generation tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholars Program includes the following aims:

• To establish a pipeline to assist individuals from underrepresented and/or disadvantaged backgrounds in gaining mentorship and research in health careers professions including nursing, medicine, and public health with a focus on HIV and HCV health disparities

• To enhance cultural competence and humility by promoting respect for the patient, their values/beliefs, and lived experiences.

• To promote comprehensive care of individuals impacted by HIV and HCV infections with a recognition of the importance of the intersection with substance use (addiction and overdose), violence, mental health, and the social determinants of health

Methods

Program establishment and overview

Generation Tomorrow was established in October 2013 by the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) in collaboration with community partners. This program was designed to be a training and field experience for Johns Hopkins University students, undergraduate and graduate, and community based health workers with the aim of increasing awareness and detection of HIV and HCV infections in Baltimore. Students and peers have the opportunity to participate in HIV and HCV testing and counseling training and are paired with a testing location in Baltimore to utilize their newly learned skillset. Additionally, the program has a weekly lecture series and hosts large scale community event to increase access to HIV and HCV testing. As of 2020, 148 students and 31 peers have been trained and placed in Generation Tomorrow. The program has partnered with 12 organizations in the Baltimore community all with the common goal to aid in the treatment and prevention of HIV and HCV. The program was deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

In 2019, this program was expanded to include a summer program called Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholars. Previously, the program had been mainly focused on Johns Hopkins students Program leadership decided to expand this experience and bring undergraduate students from across the country to Johns Hopkins for the training opportunity. The program was conceived and designed to support and attract undergraduate students nationwide that are interested in HIV and/or HCV health disparities and their intersection with substance use (addiction and overdose), violence, mental health, and social determinants of health. In 2019, the cohort consisted of 10 students. Of these students, 6 were considered underrepresented in medicine, 3 were first generation college students, and 3 were considered economically disadvantaged. The 2020 cohort consisted of 5 students. Due to COVID-19, the 2020 cohort was hosted virtually, and some students decided to defer participation. Of the 5 students hosted, 4 were considered underrepresented in medicine and 3 were first generation college students.

The generation tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholar’s program is focused on disseminating equitable healthcare practices by training and introducing more diverse and culturally competent providers into the field. A modified version of the Institute of Medicine’s Health Access Model was used as the paradigm upon which the program was built (Figure 1) [7]. The program encourages cultural competence by exposing a diverse array of learners to diverse populations, topics and experiences, fostering both transformative and experiential learning theory based opportunities. Through HIV and HCV training, as well as weekly lectures, enhanced communication is emphasized with a particular focus on non-judgmental care. The students also improve their medical knowledge and technical skills which lay the groundwork for future careers in medicine. Lastly, students are required to attend lectures focused on reducing bias and stereotyping. Addressing all of these mediators in Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholars, in addition to other interventions, will help to improve health outcomes for racial and ethnic groups and thus reduce health and health care disparities.

The key program components include mentorship and training in HIV and HCV education, testing, and counseling as well as informing students about health disparities, cultural competence, and harm reduction. The program focuses on undergraduate students that are underrepresented in nursing, public health, and medicine with an emphasis on first generation college students and individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds. In the summer of 2019, 10 students participated in the program and were hosted at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Maryland. In 2020, the program was hosted virtually due to COVID-19 and included 5 students from across the country (while the additional students deferred to the next year due to COVID-19).

Our community partner, Sisters Together and Reaching, Inc., is a non-profit, community and faith based organization that was created in 1991 in Baltimore. This organization was founded to address inequities in services to African American women and their families living with HIV/AIDS. They have been providing resources and support services to HIV infected women in their families since 1991 and to HIV infected men since 1997. The partnership between STAR and Generation Tomorrow allowed the students to participate in community outreach by providing testing in their mobile clinic, hosting testing events and block parties throughout Maryland. The partnership with this community based organization began in 2015 and continues to remain in both programs Generation Tomorrow and Generation Tomorrow: Health Disparity Scholars.

Program components

Lecture series: During the summers of 2019 and 2020, the Generation Tomorrow lecture series was presented on Tuesday and Thursday mornings or early afternoons. The guest lecturers included leaders from the CFAR, health professionals from Baltimore City, and other content experts. The goal of the lecture series was to provide additional knowledge about the relationship between HIV and/or HCV in Baltimore communities and the social determinants of health. Additionally this curriculum focused on promoting non-judgmental, compassionate, and culturally competent care. Some of the topics included: HIV/HCV Clinical Testing and Care, Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Career Profiles in Infectious Diseases, Social Determinants of Care, Trauma Informed Care, Violence Prevention, Motivational Interviewing, HIV Disparities in Men Who Have Sex with Men, Harm Reduction 101, Medical School Admissions, HIV and Sex Workers and International HIV Work.

Research and mentorship: The Health Disparity Scholars interests were assessed through a brief survey and then they were paired with a mentor for their summer research project during the 10 week program. The mentors are typically Johns Hopkins faculty members with ongoing research. The projects focus on health disparities related research which can be clinical, health services, or biomedical. The students present a poster as well as a presentation highlighting what they worked on throughout the summer. These projects are presented at the University wide C.A.R.E.S. (Career Academic and Research Experience for Students) Symposium. These mentorships are a focal point of the summer program and many mentors continue to collaborate with students’ post the formal program and some students have published with their mentors. Some of the research projects were: Substance Use Disorder and Access to Treatment Among Latinx in Baltimore City, Examining the Overlap of Alcohol Use and HCV Among People Who Inject Drugs, An Examination of the Relationship Between Homicide Rates and the Use of Deadly Force, and Substance Use and Addiction Curriculum.

Community outreach: The program includes the opportunity for the students to have an internship focused on outreach either through community based organizations or Johns Hopkins affiliated programs. The 2019 Scholars underwent mandatory training in HIV and HCV counseling and testing at the beginning of their program period. The HIV training consisted of 2 days Level 1 HIV Counseling and Testing training through the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The HCV training consisted of a one day HCV counseling and testing training conducted by the Johns Hopkins Division of Infectious Diseases. After each of the trainings, participants received testing and counseling certifications. Additionally, the students received hands on training with supervisors at their field assignments before engaging in education, testing and counseling. The 2020 cohort was unable to participate in community outreach due to the Coronavirus Pandemic.

Career advising from program leadership: The Generation Tomorrow program leadership has expertise in HIV and HCV health disparities as well as the other relevant topics discussed during the program. The leadership provides career advising to students through measures such as interview prep, as well as continues to work with students throughout the year on various projects.

Results

During close out sessions at the conclusion of the program, leadership spoke with the students about their time in the program. In discussions with the 2019 and 2020 cohorts, the following themes emerged.

Cultural competency requires that individuals attempt to fully understand the community and barriers faced

The students noted that through their community engagement work with STAR that they were able to more fully understand and appreciate the complex barriers that individuals in the Baltimore community face at the intersection of HIV/HCV health disparities, substance use, mental health, violence, and other social determinants of health. The students believed that this would make them better health professionals and researchers.

Cultural humility and empathy are critical for informed care

The students also recognized that while they may not know everything about every particular group that by showing cultural humility and empathy could help patients and community members feel empowered to share their stories and lives. Thus, this open exchange of information could enhance the care process.

Mentorship is of utmost importance and these relationships must continue beyond the program as the summer program alone will not change the students’ trajectory

Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparity Scholars continues to mentor students beyond the summer experience through interview prep, check in phone calls, and continued mentorship. Through the process, it has become evident that a 10 week summer program is not enough as students need mentors to reinforce their greatness and aptitude (dispel the myth of the imposter syndrome), and to provide guidance as the students go through the health professional school process.

Specific predictors of future success remain unclear

While the cohorts of students chose have been academically talented, it will be important to characterize the longitudinal impact of the curriculum over the course of the program. This information along with data about the students’ experiences navigating higher levels of education would be helpful to refine the curriculum of the program in future years.

Discussion

Insights from community partner

Rev. Debra Hickman, CEO and Founder of our community partners, STAR, provided insights into Baltimore’s healthcare ecosystem and how health disparities can be ameliorated in this area through community work. Baltimore residents experience a multitude of barriers to achieving health care, both preventative and curative. She explained that one of the chief issues is the misalignment between the socioeconomic resources of community members and the expectations of the medical system in which we live. For example, most doctors’ offices, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, are offering telehealth services and require the use of phones and computers. Many of these patients have phones with limited minutes or no phones at all. Rev. Hickman elaborated on this concern further by emphasizing the issues of transportation. Some transportation services are available, but they are limited and often hard to schedule. Additionally, if they do get the office, oftentimes people feel judged by their providers due to stigmatization around substance use or other perceived differences. With all of this considered, community and health care workers have to focus on meeting the community members where they are at; this begins with communicating with and developing an awareness of the struggles that pose barriers to people achieving optimal health. STAR has helped address this through various programs and events such as providing emergency financial assistance, contacting doctor’s offices, delivering medications, and hosting health education events. Rev. Hickman highlighted the importance of having the Generation Tomorrow Scholars participate with STAR’s events as it gives the next generation of healthcare workers an opportunity to go into the community and learn about varying groups of people. She spoke about how receptive the community is to the efforts of the Scholars and that the students have expressed the value in seeing the community first hand. Community engagement promotes cultural competency and allows the students to see the social determinants of health from their own eyes.

Conclusion

The lessons learned through student participant and community partner insights have proven critical for informing the current iteration of the program for our 2021 summer cohort (8 participants) which will remain virtual due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our experience has highlighted the importance of community engagement in building a framework to help train health professionals to understand the communities and individuals they serve. The community based HIV/HCV testing conducted by our students with STAR and the involvement of STAR in the development of the program allowed students to understand the barriers that are often faced among our patient population in Baltimore. We believe this will enrich their cultural competence as they move forward in their careers and be applicable to many of the communities they will work with moving forwards.

An additional key component of our program is mentorship. Students that have been traditionally underrepresented in medicine, disadvantaged populations, and first generation college students often have barriers in navigating complex systems in their pathway to health careers. Our program provides continual advising and direct mentorship to support students. The experience also provides the students with access to individuals that work directly in admissions so that they can understand what is needed to make them a competitive applicant to health professional schools. Again, we believe this ongoing mentorship and exposure to research will allow the students to overcome significant barriers and achieve their goals. Outcomes will be explored in years to come.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the participants, mentors, and community members involved in Generation Tomorrow: Summer Health Disparities Scholars as well as Sisters Together and Reaching, Inc. leadership and staff; The Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research leadership and staff; The Johns Hopkins Division of Infectious Diseases and the Viral Hepatitis Center.

Funding

Support for this project was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research [1P30AI094189]), the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and the Gilead Foundation. Additional support was provided to the senior author by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [R01DA013806].

References

- National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. AHRQ Pub. No. 20(21)-0045-EF.

- Turner A (2018) The business case for racial equity: A strategy for growth. W.K. Kellogg Foundation and Altarum.

- Jackson CS, Gracia JN (2014) Addressing health and health-care disparities: The role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep 129 Suppl 2: 57-61.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- HIV Surveillance Report (2021) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report No.: 32.

- QuickFacts: Baltimore City, Maryland [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2020.

- Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, et al. (2006) The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med 144(10): 705-714.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR (2002) Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 17(6):477-486.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams DR, Cooper LA (2019) Reducing racial inequities in health: Using what we already know to take action. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(4): 606.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vespa J, Medina L, Armstrong DM (2020) Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau 25-1124.

- Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020

- The business case for racial equity: A strategy for growth. W.K. Kellogg Foundation and Altarum

- Duffy TP (2011) The Flexner Report-100 years later. Yale J Biol Med 84(3):269-276.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A (2020) Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(35): 21194- 21200.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mullins CD, Blatt L, Gbarayor CM, Yang HK, Baquet C (2005) Health disparities: A barrier to high-quality care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 62(18):1873-1882.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wasserman J, Palmer RC, Gomez MM, Berzon R, Ibrahim SA, et al. (2019) Advancing health services research to eliminate health care disparities. Am J Public Health 109:S64-S69.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L (2001) Increasing racial and ethnic diversity among physicians: An intervention to address health disparities? National Academies Press (US).

- Bouye KE, McCleary KJ, Williams KB (2016) Increasing Diversity in the health professions: Reflections on student pipeline programs. J Healthc Sci Humanit 6(1): 67-79.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Katz JR, Barbosa LC, BenavidesVS (2016) Measuring the success of a pipeline program to increase nursing workforce diversity. J Prof Nurs 32(1): 6-14.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Betancourt JR (2003) Cross-cultural medical education: Conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad Med 78(6):560-569.

[Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2486

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Apr 05, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2002

- PDF downloads: 484