Rebleeding from Cerebral Aneurysms during 3DCT Angiography

Received: 18-Sep-2017 / Accepted Date: 09-Oct-2017 / Published Date: 16-Oct-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2167-7964.1000275

Abstract

Background and purpose: Computed Tomographic Angiography (CTA) is commonly used for the non-invasive detection of cerebrovascular lesions responsible for subarachnoid hemorrhage, but rebleeding may occur during this procedure. We investigated imaging findings and related factors in patients who experienced rebleeding during CTA in our hospital.

Materials and methods: Participants comprised 112 patients who underwent CTA for ruptured cerebral aneurysm in our hospital between January 10 and December 2015. CTA was performed using a 64-row detector system.

Results: Rebleeding occurred during CTA in 5 of 112 patients, representing a rebleeding rate of 4.5%. Mean time from initial onset of hemorrhage to CTA was shorter in patients with rebleeding (median, 88 min) than in patients without rebleeding (median, 228 min; P=0.051), and blood pressure at the time of initial treatment tended to be higher for patients with rebleeding. Patients with rebleeding showed either: a) spiral or wave-shaped hemorrhage into the cistern in which the aneurysm was located; or b) tear-drop-shaped hemorrhage within the hematoma. Patients with rebleeding were all grades 5 according to the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) and underwent CTA within 3 h of onset.

Conclusion: CTA offers excellent performance for the diagnosis of cerebral aneurysm, but the use of intravenous contrast agent may carry some risk of rebleeding. History of recent severe subarachnoid hemorrhage also appears to represent a risk factor for rebleeding. As contrast agent injection may produce hemodynamic effects, management of fluctuations in blood pressure during CTA is crucial.

Keywords: Subarachnoid hemorrhage; Aneurysm; CT; CTA; Rebleeding; Intracerebral hemorrhage; Ruptured aneurysm

Introduction

Participants comprised 112 patients who underwent CTA for ruptured cerebral aneurysm in our hospital between January 10 and December 2015 [1]. Computed Tomographic Angiography (CTA) is a non-invasive test with high diagnostic performance that enables the detection of cerebrovascular lesions responsible for subarachnoid hemorrhage and is relatively simple compared with angiography, provided the patient has no restrictions regarding the use of contrast agent [2-4]. Although CTA is widely used, we have encountered cases in which rebleeding occurred from ruptured cerebral aneurysms during CTA. Numerous reports have described the risk of rebleeding from ruptured cerebral aneurysms during angiography if angiography is performed within the first 6 h after rupture, and prognosis after rebleeding is poor [5-8]. Although many studies have discussed the value of CTA, few reports have described rebleeding from ruptured cerebral aneurysms during CTA. We report herein an investigation of imaging findings and related factors in patients who experienced rebleeding during CTA, together with a discussion of the literature.

Experimental

Subjects comprised 112 patients who underwent CTA for ruptured cerebral aneurysm in our hospital between January 2010 and December 2015. Cranial Computed Tomography (CT) was carried out after the conclusion of initial treatment, and CTA was performed after subarachnoid hemorrhage had been confirmed and blood pressure control implemented with antihypertensive agents. CTA was carried out using a Toshiba Aquilion 64-row detector system, with imaging conditions according to the standard protocol below. Image processing of the source images acquired was performed using a workstation (Zio M900 workstation, Amin Co., Tokyo, Japan), on which CTA images and multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) images were produced. Patients for whom the use of contrast agent was contraindicated for reasons such as kidney dysfunction or history of allergy to contrast agents were excluded from this study.

Results

Rebleeding during CTA occurred in 5 of 112 patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured cerebral aneurysm, representing a rebleeding rate of 4.5%. Table 1 shows the clinical attributes of patients with and without rebleeding. Mean time from onset to CTA was shorter in patients with rebleeding (median, 88 min) than in patients without rebleeding (median, 228 min; P=0.051), and blood pressure at the time of initial treatment tended to be higher for patients with rebleeding.

| No Rebleeding | Rebleeding | All | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 35 | 1 | 36 | P=0.551 |

| Female | 72 | 4 | 76 | ||

| Age | 57.4 ± 14.2 (30-82) | 57.7 ± 10.5 (39-74) | 60.2 (30-82) | - | |

| Aneurysm site | ACA | 31 | 2 | 33 | P=0.468 |

| MCA | 24 | 2 | 26 | ||

| PcomA | 28 | 0 | 28 | ||

| ICA | 9 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Posterior circulation | 15 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Aneurysm size | <7mm | 75 | 4 | 79 | P=0.634 |

| ≥ 7mm | 32 | 1 | 33 | ||

| WFNS scale | 1 | 15 | 0 | 15 | P<0.001 |

| 2 | 35 | 0 | 35 | ||

| 3 | 24 | 0 | 24 | ||

| 4 | 19 | 0 | 19 | ||

| 5 | 14 | 5 | 19 | ||

| Fisher grade | 1 | 11 | 0 | 11 | P=0.379 |

| 2 | 30 | 0 | 30 | ||

| 3 | 55 | 4 | 59 | ||

| 4 | 11 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Interval time between initial bleeding and CTA (min) | - | 228 (30-1440) | 88 ± 53.5 (50-180) | 218 (30-1440) | - |

Table 1: Clinical data of patients with aneurysmal SAH.

Two patterns of imaging findings were observed in patients with rebleeding. These comprised spiral or wave-shaped hemorrhage into the cisterna in which the aneurysm was located, or a tear-drop-shaped hemorrhage within the hematoma.

Although no significant differences were seen between patients with and without rebleeding in terms of clinical attributes such as sex, age, or blood pressure at an initial correspondence patients with rebleeding were all grade 5 according to the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) and underwent CTA within 3 h of onset.

Rebleeding Cases

The cases of rebleeding encountered at our hospital between January 2010 and December 2015 are described below. Table 2 shows rebleeding patients in our series were summarized.

| Case | Age (Year/Sex) | Rebleeding interval (min) | Aneurysm site | Size (mm) | WFNS grade | Fisher group | Therapy | GOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54/F | 180 | MCA | 2 | 5 | 3 | Clip | 2 |

| 2 | 39/F | 60 | ICA | 2 | 5 | 3 | Coil | 4 |

| 3 | 58/F | 90 | ACA | 5 | 5 | 3 | (-) | 1 |

| 4 | 63/M | 50 | MCA | 10 | 5 | 4 | Clip | 1 |

| 5 | 66/F | 60 | ACA | 3 | 5 | 3 | Coil | 1 |

ICA: Internal Carotid Artery; WFNS: World Federation of Neurological Surgeon Scale

Table 2: Clinical data of rebleeding patients with aneurysmal SAH.

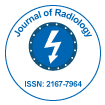

Case 1 (Figure 1)

A 54-yr-old woman presented with onset marked by sudden impairment of consciousness (grade 5). Cranial CT showed a thick subarachnoid hemorrhage in the right Sylvian fissure, and CTA revealed aneurysm of the right Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA). Contrast agent was observed leaking from the aneurysm into the cistern. Craniotomy and clipping of the ruptured aneurysm and hematomectomy of the intracerebral hematoma were performed on Day 0, but no improvement in consciousness was obtained, and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score after 1 month was Vegetative State (VS).

Figure 1: A 54-year-old woman presented with onset marked by sudden impairment of consciousness. A) CT before CTA. B) CT after CTA C) CTA source image. White arrow indicated rebleeding from right middle cerebral aneurysm. D) MPR sagittal section. White triangle indicated rebleeding manifesting like Cock-Screw. E) CTA F) Right CAG. Black arrow indicated right middle cerebral aneurysm.

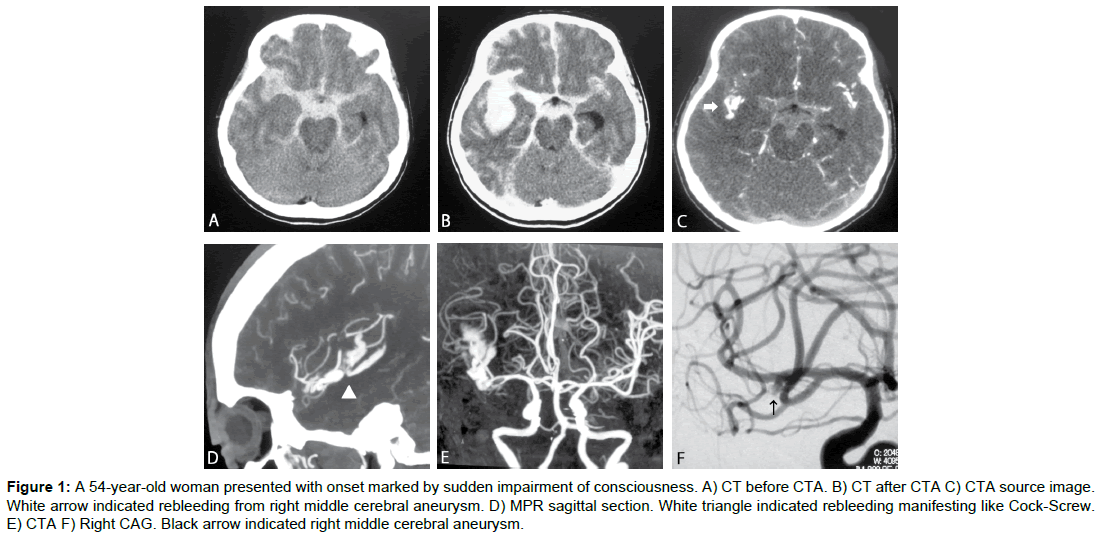

Case 2 (Figure 2)

A 39-yr-old woman presented with onset marked by sudden impairment of consciousness (grade 5). Cranial CT showed subarachnoid hemorrhage centered on the basal cistern. CTA revealed an aneurysm at the branching point of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the anterior choroid artery, with contrast agent leaking in a spiral shape from the tip of the aneurysm into the basal cistern. Coil embolization of the ruptured aneurysm was performed on Day 0. GOS score after 1 month was moderate disability (MD).

Figure 2: A 39-year-old woman presented with onset marked by sudden impairment of consciousness (grade 5). A) CT before CTA. B) CT after CTA C) CTA source image. White arrow indicated rebleeding from right internal carotid artery-anterior choroidal artery aneurysm manifesting like Cock-Screw. D) MPR coronal section. White triangle indicated rebleeding manifesting like Cock-Screw. E) CTA F) Right CAG. Black arrow indicated right internal carotid artery-anterior choroidal artery aneurysm.

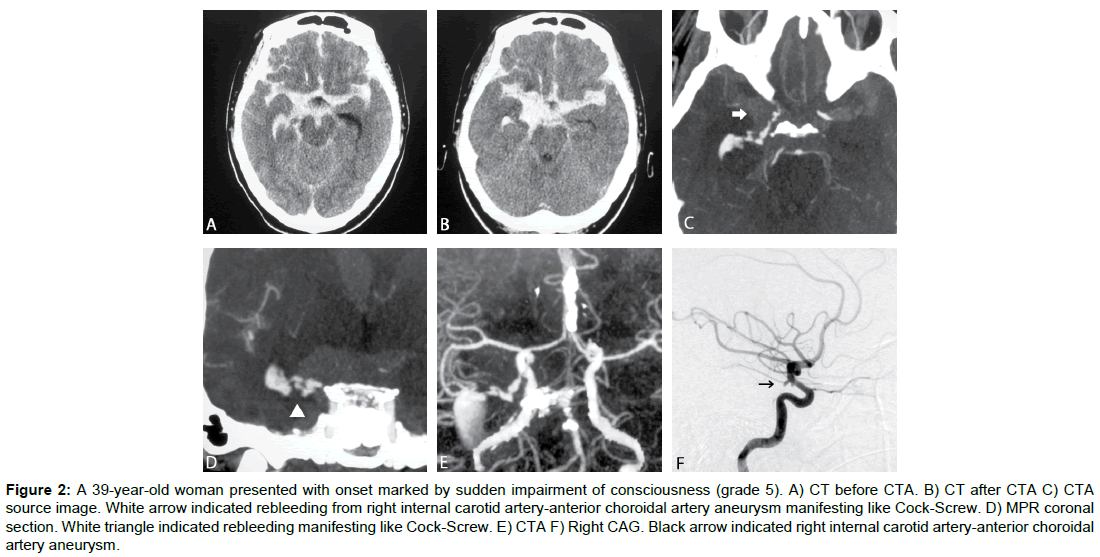

Case 3 (Figure 3)

A 53-yr-old woman presented with onset marked by seizure (grade 5). Cranial CT showed subarachnoid hemorrhage, mainly in the basal cistern. CTA revealed aneurysm of the left anterior cerebral artery. Contrast agent was pooled in the basal cistern. After rebleeding, the patient showed a sudden drop in blood pressure, and died on Day 16 without having undergone curative surgery for the source of hemorrhage.

Figure 3: A 53-year-old woman presented with onset marked by seizure (grade 5). A) CT before CTA. B) CTA source image. White arrow indicated rebleeding from left anterior cerebral artery aneurysm manifesting like Tear Drop. C) MPR coronal section. White triangle indicated rebleeding manifesting like Tear Drop. D) CTA E) Left CAG. Black arrow indicated left anterior cerebral artery aneurysm.

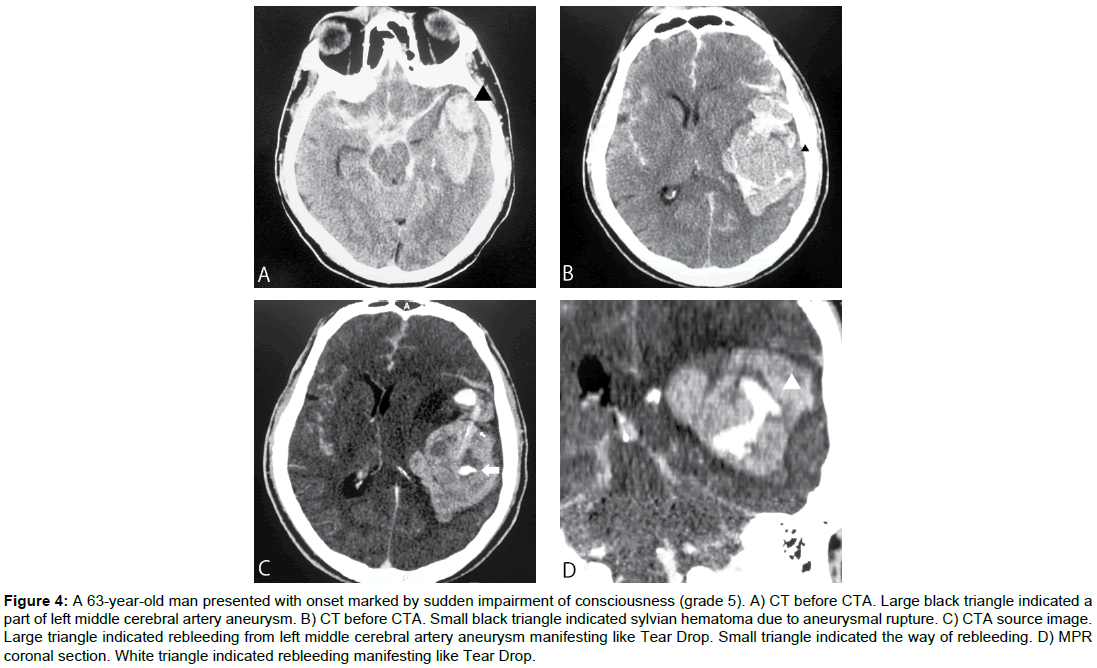

Case 4 (Figure 4)

A 63-yr-old man presented with onset marked by sudden impairment of consciousness (grade 5). Cranial CT showed intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage, mainly in the left Sylvian fissure and temporal lobe. CTA revealed aneurysm of the left middle cerebral artery, with contrast agent leaking into the intracerebral hematoma. Craniotomy and clipping of the ruptured aneurysm and hematomectomy of the intracerebral hematoma were performed on Day 0, but the intracerebral hematoma enlarged and worsened and the patient died from concomitant heart failure on Day 2.

Figure 4: A 63-year-old man presented with onset marked by sudden impairment of consciousness (grade 5). A) CT before CTA. Large black triangle indicated a part of left middle cerebral artery aneurysm. B) CT before CTA. Small black triangle indicated sylvian hematoma due to aneurysmal rupture. C) CTA source image. Large triangle indicated rebleeding from left middle cerebral artery aneurysm manifesting like Tear Drop. Small triangle indicated the way of rebleeding. D) MPR coronal section. White triangle indicated rebleeding manifesting like Tear Drop.

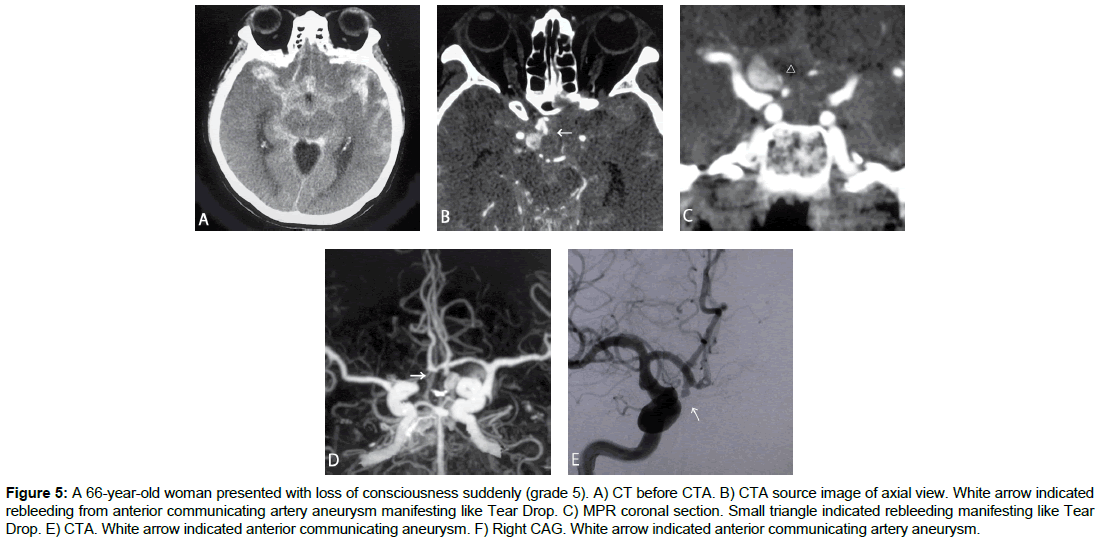

Case 5 (Figure 5)

A 66-yr-old woman presented with loss of consciousness suddenly (grade 5). Cranial CT showed intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage, mainly in the right frontal lobe. CTA revealed anterior communicating artery aneurysm, with contrast agent leaking into lamina terminalis cistern. Coil embolization for ruptured anterior communicating aneurysm was performed on Day 0, but heart failure due to catecholamine cardiomyopathy was complicated and died on Day 7.

Figure 5: A 66-year-old woman presented with loss of consciousness suddenly (grade 5). A) CT before CTA. B) CTA source image of axial view. White arrow indicated rebleeding from anterior communicating artery aneurysm manifesting like Tear Drop. C) MPR coronal section. Small triangle indicated rebleeding manifesting like Tear Drop. E) CTA. White arrow indicated anterior communicating aneurysm. F) Right CAG. White arrow indicated anterior communicating artery aneurysm.

Discussion

To establish treatment strategies in cases of subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured cerebral aneurysm, detailed investigation of the source of hemorrhage and consideration of options to prevent rebleeding are required. Cerebral Angiography, Cranial Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA), and CTA are all diagnostic procedures that can be used for this purpose.

Although cranial angiography is a vital test with high diagnostic performance for the diagnosis of cerebral aneurysm, performance of this test within 6 h of the onset of subarachnoid hemorrhage increases the risk of rebleeding, with a reported frequency of 3.3% to 4.8% [5,6,8]. Rebleeding is particularly common in patients at severe grades or with aneurysms of the ICA or MCA [5-8].

Cranial MRA offers inferior diagnostic performance to CTA with respect to the detection of cerebral aneurysm on some points [9,10] but is regarded as a valuable screening method. As MRA also provides less surgical information compared with CTA and the diagnostic concordance rate between different doctors is poor compared with angiography, the technique is most often only used as a supplementary method of diagnosis [11].

CTA offers excellent performance for the diagnosis of cerebral aneurysm, and numerous reports have described its value [6,12]. The capacity of CTA for the detection of cerebral aneurysm is reportedly equivalent to that of angiography, and this modality provides more information for performing surgical procedures, and can be performed non-invasively within a short period of time, making it useful for the diagnosis of cerebral aneurysm [13,14].

Nakatsuka et al. performed CTA on 28 patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and reported a rebleeding rate of 17.9% [15], while Hashiguchi et al. reported rebleeding in 2 of 61 patients (3.3%) [16]. As rebleeding also occurred in 4 patients (6.7%) in our own series, occurrence during CTA is far from infrequent.

The rate of rebleeding in our hospital in the present study was almost the same as that reported elsewhere, and one characteristic of all the patients with rebleeding was the previous presence of grade 5 subarachnoid hemorrhage. Table 2 shows a summary of reported cases [16-21] Rebleeding was more common in patients with severe subarachnoid hemorrhage and tended to be more frequent in those who underwent CTA within 3 h of initial bleeding, but no consistent findings were seen with respect to aneurysm location. Outcomes were poor for patients who experienced rebleeding. In addition to the performance of testing, other factors indicating a high risk of rebleeding include early period after onset, with many cases reported 2 h after onset [22] and as short duration after onset has been reported as an independent risk factor for rebleeding [11] the risk entailed in the early performance of this test after onset must be kept in mind, and efforts must be made to adjust the timing of this test in accordance with circumstances.

To determine a treatment policy for ruptured cerebral aneurysm with intracerebral hemorrhage, however, some cases require identification of the source of hemorrhage at an early stage and consideration of surgical procedures to prevent rebleeding, so whether CTA should be performed must be considered according to the individual situation of the patient.

In imaging findings from CTA in cases of rebleeding, contrast agent was visualized in a spiral shape in some cases and as a teardrop- shaped mass in others. This difference was due to the location of rebleeding in the aneurysm, and whether the contrast agent was diluted by cerebrospinal fluid was also a contributing factor [19]. Rebleeding into a cerebral cistern, as in Cases 1 and 2, was visualized as a spiral shape on CTA, whereas rebleeding into a hematoma cavity, as in Cases 3, 4 and 5, appeared as a mass (daughter aneurysm). Because these findings are easily identified as signs of contrast agent leakage on the CTA source image, whether rebleeding has occurred must be confirmed immediately after CTA scanning. Presence or absence of rebleeding should be ascertained on the source image during CTA for severe-grade patients and patients in the early phase of subarachnoid hemorrhage in particular.

Many points regarding the mechanisms of onset for rebleeding during CTA remain unclear. During angiography, arterial injection of contrast medium may cause a localized rise in blood pressure, which has been reported as contributing to rebleeding [21]. CTA utilizes intravenous injection, which does not contribute to a transient rise in blood pressure, and is therefore believed to not increase the risk of rebleeding [15,21,7]. As contrast agent is used intravenously during the performance of CTA, however, the possibility of some involvement in rebleeding cannot be ruled out. Contrast agent injection reportedly produces hemodynamic effects, resulting in a temporary rise in systemic blood pressure [23-25] and fluctuations in blood pressure during CTA may contribute to rebleeding. Management of fluctuations in blood pressure during the performance of CTA is therefore crucial.

Conclusion

We investigated cases of rebleeding from ruptured cerebral aneurysms during the performance of CTA at our hospital. Although CTA is an extremely useful examination when considering treatment for ruptured cerebral aneurysm, rebleeding can occur during scanning in some patients and care is therefore required.

References

- Sankhla SK, Gunawardena WJ, Coutinho CMA, Jones AP, Keogh AJ (1996) Magnetic resonance angiography in the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: A study of 51 cases. Neurorad 38: 724-729.

- Chappell ET, Moure FC, Good MC (2003) Comparison of computed tomographic angiography with digital subtraction angiography in the diagnosis of cerebral aneurysms: A meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 52: 624-631.

- Karamessini MT, Kagadis GC, Petsas T, Karnabatidis D, Konstantinou D, et al. (2004) CT angiography with three-dimensional techniques for the early diagnosis of intracranial aneurysms: Comparison with intra-arterial DSA and the surgical findings. Eur J Rad 49: 212-223.

- Tipper G, U-King-Im JM, Price SJ, Trivedi RA, Cross JJ, et al. (2005) Detection and evaluation of intracranial aneurysms with 16-row multislice CT angiography. Clin Rad 60: 565-572.

- Komiyama M, Tamura K, Nagata Y, Fu Y, Yagura H, et al. (1993) Aneurysmal rupture during angiography. Neurosurg 33: 798-803.

- Kusumi M, Yamada M, Kitahara T, Endo M, Kan S, et al. (2005) Rerupture of cerebral aneurysms during angiography: A retrospective study of 13 patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir 147: 831-837.

- Saitoh H, Hayakawa K, Nishimura K, Okuno Y, Teraura T, et al. (1995) Rerupture of cerebral aneurysms during angiography. Am J Neurorad 16: 539-542.

- Yasui T, Kishi H, Komiyama M, Iwai Y, Yamanaka K, et al. (1996) Very poor prognosis in cases with extravasation of the contrast medium during angiography. Surg Neurol 45: 560-564.

- Okahara M, Kiyosue H, Yamashita M, Nagatomi H, Hata H, et al. (2002) Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance angiography for cerebral aneurysms in correlation with 3D–digital subtraction angiographic images. Stroke 33: 1803-1808.

- Schwartz RB, Tice HM, Hooten SM, Hsu L, Stieg PE (1994) Evaluation of cerebral aneurysms with helical CT: correlation with conventional angiography and MR angiography. Radiology 192: 717-722.

- Ohkuma H, Tsurutani H, Suzuki S (2001) Incidence and significance of early aneurysmal rebleeding before neurosurgical or neurological management. Stroke 32: 1176-1180.

- Zaehringer M, Wedekind C, Gossmann A, Krueger K, Trenschel G, et al. (2002) Aneurysmal re-rupture during selective cerebral angiography. Eur Rad 12: S18-S24.

- Matsumoto M, Sato M, Nakano M, Endo Y, Watanabe Y, et al. (2001) Three-dimensional computerized tomography angiography-guided surgery of acutely ruptured cerebral anuerysms. J Neurosurg 94: 718-727.

- Villablanca JP, Martin N, Jahan R, Gobin YP, Frazee J, et al. (2000) Volume-rendered helical computerized tomography angiography in the detection and characterization of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 93: 254-264.

- Nakatsuka M, Mizuno S, Uchida A (2002) Extravasation on three-dimensional CT angiography in patients with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage and ruptured aneurysm. Neuroradiol 44: 25-30.

- Hashiguchi A, Mimata C, Ichimura H, Morioka M, Kuratsu JI (2007) Rebleeding of ruptured cerebral aneurysms during three-dimensional computed tomographic angiography: report of two cases and literature review. Neurosurg Rev 30: 151-154.

- Holodny AI, Farkas J, Schlenk R, Maniker A (2003) Demonstration of an actively bleeding aneurysm by CT angiography. Am J Neurorad 24: 962-964.

- Josephson SA, Dillon WP, Dowd CF, Malek R, Lawton MT, et al. (2004) Continuous bleeding from a basilar terminus aneurysm imaged with CT angiography and conventional angiography. Neurocrit Care 1: 103-106.

- Nagai M, Koizumi Y, Tsukue J, Watanabe E (2008) A case of extravasation from a cerebral aneurysm during 3-dimensional computed tomography angiography. Surg Neurol 69: 411-413.

- Nakada M, Akaike S, Futami K (2000) Rupture of an aneurysm during three-dimensional computerized tomography angiography. J Neurosurg 93: 900.

- Ryu CW, Kim SJ, Lee DH, Suh DC, Kwun BD (2005) Extravasation of intracranial aneurysm during computed tomography angiography: mimicking a blood vessel. J Comput Assist Tomogr 29: 677-679.

- Fujii Y, Takeuchi S, Sasaki O, Minakawa T, Koike T, et al. (1996) Ultra-early rebleeding in spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 84: 35-42.

- Lasser EC, Lamkin GE (2002) Mechanisms of blood pressure change after bolus injections of x-ray contrast media. Acad Rad 9: S72-S75.

- Morcos SK, Dawson P, Pearson JD, Jeremy JY, Davenport AP, et al. (1998) The haemodynamic effects of iodinated water soluble radiographic contrast media: A review. Eur J Rad 29: 31-46.

- Morcos SK (2003) Effects of radiographic contrast media on the lung. Br J Rad 76: 290-295.

Citation: Yoshida K, Suzuki K, Ueki Y, Higo T (2017) Rebleeding from Cerebral Aneurysms during 3DCT Angiography. OMICS J Radiol 6: 275. DOI: 10.4172/2167-7964.1000275

Copyright: ©2017 Yoshida K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4834

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Apr 06, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4031

- PDF downloads: 803