Research Article Open Access

Reactive Attachment Disorder in Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) Affected by HIV/AIDS: Implications for Clinical Practice, Education and Health Service Delivery

Paul Narh Doku*

Department of Psychology, University of Ghana, Box LG 84, Legon – Accra, Ghana

- *Corresponding Author:

- Paul Narh Doku

Department of Psychology

University of Ghana, Box LG 84

Legon – Accra, Ghana

Tel: 00233543903139

E-mail: pndoku@ug.edu.gh

Received Date: January 22, 2016; Accepted Date: February 16, 2016; Published Date: February 23, 2016

Citation: Doku PN (2016) Reactive Attachment Disorder in Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) Affected by HIV/AIDS: Implications for Clinical Practice, Education and Health Service Delivery. J Child Adolesc Behav 4:278. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000278

Copyright: © 2016 Doku PN. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

Background: Orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) affected by HIV/AIDS frequently experience placement/ residential changes, inconsistent caregivers, abuse, neglect, disruptions in their lives and several mental health problems. This may lead to a disorder of emotional functioning, reactive attachment disorder (RAD), where the child exhibits wary, watchful, and emotionally withdrawn. Despite its clinical importance, nothing is known about RAD among OVC. This study investigated: (1) whether RAD symptoms can occur in children affected by HIV/AIDS; (2) association between RAD and other psychiatric symptoms; (3) possible aetiological or contextual factors for high RAD symptom; and (4) any interactive, cumulative effects between the aetiological or contextual factors (both risks and protective) for higher RAD symptoms. Method: In a cross-sectional survey, caregivers of 191 OVC and 100 non-OVC completed questionnaires on mental health problems including RAD and contextual variables. Results: The results demonstrated that RAD is present in OVC and that RAD symptoms may be as a result of environmental factors. The study also found high levels of RAD comorbidity with other disorders including depression, conduct problems and hyperactivity. Finally, the results indicate that experiencing more neglect and psychological abuse among OVC increases their likelihood of exhibiting RAD symptoms five-fold. Conclusion: The paper discusses the clinical implications of these findings for service development for this vulnerable group in the community and concluded that among children affected by HIV/AIDS, RAD was not rare.

Keywords

Orphans; HIV/AIDS; Community

Background

Previous studies have shown that within the context of HIV/AIDS, compared to other children, orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) were at increased risk for numerous developmental, emotional and behavioral problems including depression, self-esteem, suicide ideation, anxiety, conduct problems, post-traumatic stress disorder delinquency problems [1-6]. A great majority of OVC has also been maltreated/abused, neglected, experiences placement instability and lives in less socially supportive households [1,5,7].

Maltreated and abused children are noted to have difficulty expressing their feelings and appreciating the distress of others [8-11]. Yet there has been no attention given to relationship difficulties among these children. Reactive attachment disorder (RAD) is an APA and DSM-IV-TR psychiatric malady that affects one’s ability to form connections with others or develop appropriate social relatedness [12,13]. RAD closely resembles internalizing disorders and so children with RAD exhibit watchful, wary and emotionally withdrawn behaviours [14-16].

There are 2 subtypes of RAD, namely inhibited RAD which is marked by frozen watchfulness, contradictory communication, extreme isolation, hypervigilance and highly ambivalent responses [12,13,17], and disinhibited RAD which results in excessive/ inappropriate social familiarity, diffuse attachment or lack of discriminate attachment [18]. Although RAD has been little researched, it is a condition that is suggested to be associated with multiplacement experiences, institutional upbringing or with highly neglectful and abusive family rearing [12,13,15,19].

Other researchers noted that RAD affects children living in harsh conditions such as orphanages where nutritional, physical and emotional care are not adequately provided [9,10,11,20]. Gilbert and colleagues [17] also found that child maltreatment increases the risk for psychological disorders including RAD. Children diagnosed with RAD are more likely to have multiple comorbidities with other disorders including hyperactivity, aggression, and attention deficit, as well as emotional problems including depression and lack of empathy [19,21].

No data exists on the presence of RAD symptoms among children affected by HIV/AIDS and its co-existence with other psychiatric disorders. This vulnerable subset of society may be at increased risk for RAD because maltreatment, inconsistent caregivers, multiplacement and disruptions in their lives are common than for the general population. Certainly, issues surrounding RAD may be helpful in understanding psychiatric detrimental behaviours in these children. The present study therefore aimed to investigate: (1) whether RAD symptoms can occur in children affected by HIV/AIDS; (2) association between RAD and other psychiatric symptoms; (3) possible aetiological or contextual factors for higher RAD symptoms; and (4) any interactive, cumulative effects between the aetiological or contextual factors (both risks and protective) for higher RAD symptoms.

Method

Research design and setting

The study was given ethical approval by the Institutional Research Ethics Review Boards of the University of Glasgow and the Research Unit of the Ghana Health Service. The details of the study’s methodology including the study settings, participants and sampling have been described elsewhere [7]. But briefly, the present study was designed and conducted as a community based cross-sectional survey design utilizing questionnaires. The study was conducted in the rural and urban areas of the Lower Manya Krobo District of Ghana.

Measure

Mental health problems: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used. The SDQ is a brief behavioural and emotional screening questionnaire for 3-16 years olds [22,23]. It contains 25 items, covering 5 subscales: emotional symptoms; conducts problems; hyperactivity/inattention; peer relationship problems; and prosocial behaviour. It can be completed by children themselves, caregivers, or teachers. In this study, the caregivers completed the SDQ.

Relationship problems questionnaire (RPQ): The RPQ is a 10-item parent and teacher-report screening instrument for RAD symptoms [18,24]). In large general population twin sample, the RPQ had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.85), and factor analysis identified that 6 items describe inhibited RAD behaviours and 4 items describe disinhibited RAD behaviours [25].

Perceived socioeconomic status: Youth perceived SES was assessed using the MacArthur Subjective SES ladder scale. The ladder comprised of 10 geographical rungs. The youth were asked to place themselves on the rung (level) where they think they stand (in terms of money, jobs and good schooling) relative to other people in the Manya Krobo Districts.

Stigma, discrimination and social exclusion: This measured using an adapted version of items taken from the Rwandan Survey Scale. The items were found to have good consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76. The measure captures sense of community stigma and discriminatory attitudes by exploring both the childand caregiver’s perception and experiences of stigma and social exclusion [26].

Child abuse: Items were taken from two previously validated measures (Conflict Tactics Scale and South African Demographic and Health Survey) to assess these variables. The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) was originally developed by Strauss to provide a measure of conflict resolution events that involve violence by obtaining data on possible dyadic combinations of family members [27]. It has since been used in over 70,000 empirical studies and thoroughly evaluated in over 400 of them [27]. The present study utilized the version of the parentto- child scales to assess the child’s exposure to and experience of violence (direct and indirect), abuse and maltreatment corporal punishment within the household.

Child labour: These variables were measured using the Survey of Activities of Young People (SAYP) developed by the Statistics South Africa Services to collect data on work-related activities among children [28]. It was used to measure and distinguish common child work roles to more critical at-risk activities of being absence at school to undertake household responsibilities or engage in begging, selling and other related child labour duties.

Social support: This was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) scale that consists of 12 items measuring perceived social support from the family, friends and significant others. The original MSPSS internal reliability were 0.91, 0.87 and 0.85 Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for support from significant others, family and friends respectively [29]. The present study found similarly high Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of 0.80, 0.86, 0.91 and 0.88 for support from family, friends, significant others and total (full scale) respectively.

Procedure

There was a pilot preceding the present study to validate the study instruments in the research setting. The main survey worked with four categories of households: ‘AIDS orphaned households’ (families that contained AIDS orphans), ‘other orphans households’ (families containing orphans from causes other than AIDS), “HIV/AIDSinfected caregiver households” (those containing a caregiver infected with HIV/AIDS) and ‘non-affected households’ (those containing neither an orphaned child nor HIV/AIDS-infected caregiver). The latter group is interchangeably referred to as “intact families”

An orphan in the present study refers to a child between 10 and 17 years who is bereft of at least one parent to death. OVC is used to identify a child who is 17 years or below and has either lost at least a parent or is living with HIV/AIDS-infected caregiver whilstAIDSorphans is defined as children who have lost at least one parent to AIDS. The latter term is used interchangeably as children orphaned by AIDS or AIDS-orphaned children. ‘Caregiver’ is defined as the adult in the household who primarily cares for the child participant and was not necessarily a biological parent. Caregiver is used interchangeably as parent in this study. To identify whether children lost one or both parents from AIDS, verbal autopsy (VA) was used because caregivers were often unaware of or did not wish to disclose the parental cause of death and there was difficulty in obtaining accurate death certificates [30].

Participants were first screened for study eligibility after which written informed assents and consents were then obtained from the caregivers. Upon assenting/consenting, participants completed the survey questionnaires privately with the researcher that followed the steps described by Thomas [31]. The presence of other family members was completely avoided. The entire assessment inventory took about 30 to 45 minutes to complete.

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Participants (Table 1)

Approximately 58% of caregivers had no more than senior secondary level education. Majority of caregivers (62%) worked mainly in farming, driving, trading or as artisans whilst 13% of them were unemployed. There were 51% female, and ethnic origin was 63% krobos. There was an average of 4.3 people living in the household. Overall, 62% of all children had moved between 2 or more times. The majority of the children (81.8%) were currently attending school. The proportion of households with unemployed parents was higher among children living with HIV/AIDS-infected parents (38%) than AIDSorphans (9.5%), other-orphans (9%) and non-orphaned children (7%). The socio-demographic statistics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

| Non-orphaned and vulnerable children (n=100) | AIDS-orphaned vulnerablechildren(n=74) | Other-orphans (n=67) | Children with HIV/AIDS infected parent/caregiver (n=50) | P-value(t-test/chi-square) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11.53 (2.683) | 13.78 (2.624) | 13.09 (2.673) | 14.84 (2.324) | F=21.131c |

| Gender: Girls | 52 | 50 | 50.7 | 48 | |

| Boys | 48 | 50 | 49.3 | 52 | n. s. |

| aEthnicity: Dangme/Krobo | |||||

| 63.00% | 59.50% | 73.10% | 56.00% | X=40.051c | |

| Household size | 4.98 (0.995) | 3.73 (0.969) | 4.27 (1.226) | 3.96 (1.068) | F=22.604c |

| No. of changes in residence | 1.35 (1.336) | 2.76 (1.524) | 3.09 (1.685) | 1.72 (1.471) | F=23.844c |

| No. of siblings | 1.21 (0.946) | 1.95 (0.935) | 2.22 (1.277) | 2.44 (1.198) | F=19.807c |

| aLocation where child lives: urban | 50.00% | 60.80% | 59.70% | 58.00% | n. s. |

| bAge child first bereaved | 6.27 (4.339) | 8.81 (3.456) | |||

| Parental educational level: > Junior Secondary | |||||

| Parental unemployment | 7.00% | 9.50% | 9.00% | 38.00% | X=39.695c |

| Parental Loss:Mother | - | 33.80% | 34.30% | - | |

| Father | - | 37.80% | 41.80% | - | n. s. |

| Both | - | 28.40% | 23.90% | - | |

| Religion: Christianity | 69.00% | 48.70% | 44.80% | 56.00% | X=36.271c |

aDenotes significance at the 0.05 level, bdenotes significance at the 0.01 level, cdenotes significance at the 0.001 level.

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

Association between socio-demographic factors, contextual factors and RAD

Bivariate Pearson correlations indicate that higher RAD scores were related to increased age (r=0.278, p=0.001), frequent changes in residence/placement instability (r=0.310, p < 0.001), higher scores on domestic violence (r=0.226, p=0.001), child abuse (r=0.287, p=0.001) and child labour (r=0.230, p=0.001), AIDS related stigma (r=0.294, p=0.001), higher depression (r=0.299, p=0.001) and more number of siblings/children living in household (r=0.209, p=0.001).

Similarly higher RAD scores were associated with lower social support (r=0-.316, p=0.001), lower household size (r -0.174, p=0.001) and lower socioeconomic status (r=-0.291, p=0.001).Children who are presently out of school reported higher RAD than those in school (t=2.986, p < 0.01). Gender, type of orphanhold and age at first bereavement showed no significant association with RAD.

Association between RAD and other psychiatric symptoms

Children who scored high on the RAD scale were also likely to score high on the SDQ and all its subscales. The Pearson correlation between the RAD Scale and SDQ total difficulties score was 0.394 (p < 0.001), the SDQ emotional problems subscale 0.351 (p < 0.001), the SDQ conduct problems subscale 0.209 (p < 0.001), the SDQ peer relations subscale 0.279 (p < 0.001), the SDQ hyperactivity subscale 0.172 (p < 0.001) and the SDQ prosocial subscale - 0.014 (p=n. s.).

Mediating effects of contextual variables on associations between OVC and RAD (Table 2)

Linear regression analyses performed on the caregivers’ reports indicated that orphanhood by AIDS, orphanhood by other causes and living with an HIV/AIDS-infected caregiver were individually, independently associated with higher RAD symptom in models that controlled for relevant socio-demographic factors. The independent significant associations between orphanhood by AIDS, orphanhood by other causes and RAD remained significant but weaken (partial mediation) after controlling separately for contextual factors such as SES (model 3), stigma (model 4), social support (model 5), child abuse (model 6) and child labour (model 7). However, these associations with more RAD symptoms were completely eliminated (full mediation) in subsequent models that controlled for both sociodemographic factors and all contextual factors (model 8). With regard to living with HIV/AIDS-infected caregivers, its association with RAD was completely eliminated (full mediation) in the models that controlled independently for contextual factors (models 3-7) as well as the one the adjusted for combined contextual effects (model 8).

| Source | Unadjusted Model1 | Socio-demographic factors1 | Socioeconomic factors2 | AIDS Stigma3 | Social Support3 | Child Abuse3 | Child Labour1 | Sociodemographicand all contextual factors4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | |

| Orphaned by AIDS | ||||||||

| 0.559c | 0.363c | 0.129a | 0.174b | 0.165b | 0.146a | 0.162b | 0.102 | |

| Orphaned by other causes | 0.576c | 0.396c | 0.136a | 0.153b | 0.109 | 0.135a | 0.108 | 0.086 |

| Living with HIV/AIDS infected parent | .499c | .326c | -0.013 | -0.027 | -0.061 | 0.039 | 0.029 | 0.063 |

| R-Square | 0.161 | 0.241 | 0.253 | 0.133 | 0.264 | 0.267 | 0.143 | 0.153 |

| F/F- Change | 54.388c | 5.918c | 5.705c | 4.944c | 5.783c | 3.395a | 6.598c | 3.404a |

aDenotes significance at the 0.05 level, bDenotes significance at the .01 level,cDenotes significance at the 0.001 level

Table 2: Multivariate associations between orphanhood by AIDS, orphanhood by other causes, living with an HIV/AIDS-infected parents, and RAD controlling for relevant socio-demographic and contextual factors.

Interaction effects between identified contextual variables (risk and protective factors) for RAD (Tables 1 and 2)

In a pattern-seeking and interaction effects exploration using loglinear analyses, three two-way interaction effects were identified concerning scoring above the mean for likely RAD. First, interaction effect showed that perceived stigma was associated with likelihood of exhibiting RAD symptoms. More than half (56%) of children who reported more stigma showed RAD symptoms while only 32% of those who reported less stigma showed RAD symptoms (χ2=15.302, p < 0.001). Approximately 90%, 85%, 61% and 38% of children living with HIV/AIDS-infected parents, AIDS-orphaned, other-orphans, and nonorphaned children respectively reported been stigmatized (χ2=58.766, p < 0.001). Secondly, engagement in child labour and RAD symptoms showed a two-way interaction effect, with 51% of child labourers exhibiting RAD symptoms, compared to 45% of non-child labourers.

Significantly, more OVC are child labourers compared to comparison children (χ2=51.846, p < 0.001). The third two-way interaction effect showed that OVC status was related to RAD symptoms (64%, 65%, 61% and 16% of children living with HIV/ AIDS-infected parents, AIDS-orphaned, other-orphans, and nonorphaned children respectively exhibited RAD symptom;χ2=59.268, p < 0.001).

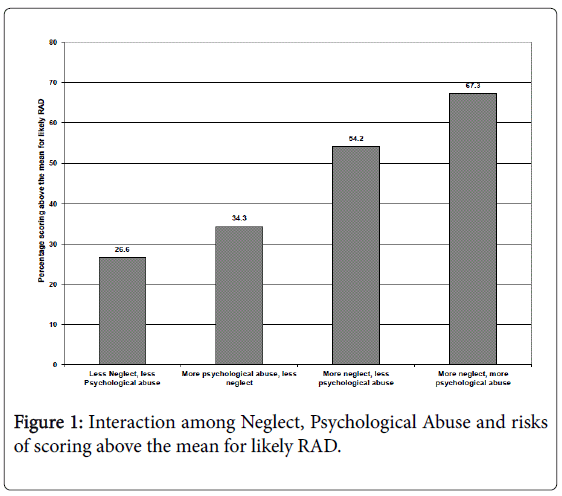

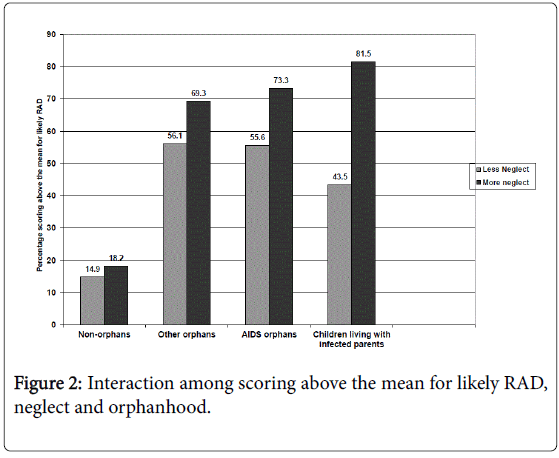

Log-linear analyses also identified two three-way interaction effects related to likelihood for RAD symptoms. First, there was an interaction between neglect, psychological abuse and RAD symptoms (χ2=9.106, p < 0.01). The interaction indicates that children who were less psychologically abused and less neglected form the group showing the lowest likelihood for RAD symptoms (27%). When children experience more psychological abuse and more neglect, the likelihood of exhibiting RAD symptoms was heightened more than two-fold to 67%. Second, there was interaction effect between neglect, OVC and likelihood for RAD symptoms. Non-orphans who were less neglected are those displaying the lowest likelihood for RAD symptoms (14.9%). Children who are living with HIV/AIDS-infected parents and are frequently neglected are the group showing the highest likelihood for RAD symptoms (81.5%). For children orphaned by AIDS and other orphans, the likelihood for RAD symptoms was remarkably, significantly high (approximately 56%) even with low neglect, and this increased to 69.3% and 73.3% for other orphans and children orphaned by AIDS respectively with frequent neglect (Figures 1and 2).

Discussion

The results of the present study confirm the findings of previous researches that children affected by HIV/AIDS are at significantly increased risk for mental health problems compared to children from non-affected, intact families [1-6]. In the OVC sample, over 65% caregivers reported enough symptom scores to suggest that their children were suffering from mental health problems and they were significantly more likely to have symptoms of conduct disorder, hyperactivity, emotional problems (depression and anxiety) and problems with peer relations.

With regard to the first aim of this study to investigate whether RAD symptoms can occur in children affected by HIV/AIDS, the results showed that the OVC sample in this study had significantly more symptom scores for RAD reported for them compared to children from intact families. This study is the first to have demonstrated heightened symptoms of RAD among children affected by HIV/AIDS. Although RAD is considered a unique, rare relationship disorder in the general population [29], it appears that among children affected by HIV/AIDS, RAD is not a rare condition. The fact that RAD has mostly been found in institutionalized children suggests, speculatively that these children (OVC) may be living under conditions similar to those of orphanages, perhaps being maltreated. The prevalence rate for RAD among OVC are two to three times higher than those found among other vulnerable clinical and community samples elsewhere [19], highlighting the worrying nature of the present finding for Ghanaian OVCs. This high prevalence of RAD raises clinical and therapeutic challenges for the caregivers of these children as there is little known empirical and evidence-based treatment for RAD. The limited available treatments are mainly untested and hugely controversial [32,33].

With regard to the second aim to investigate the association between RAD and other psychiatric symptoms; the findings shows that, within the sample of children affected by HIV/AIDS, RAD symptoms were highly associated with higher conduct problems, emotional problems, hyperactivity and peer relationship difficulties. It has been consistently shown that children diagnosed with RAD had a range of comorbid diagnoses, some of which may have been previously unrecognised by services [15,19,21,34]. The third aim was to investigate possible aetiological factors for RAD symptoms. The present study have shown that, among the OVC, higher RAD symptoms were associated with increased age, frequent changes in residence/placement instability, domestic violence, child abuse, child labour, AIDS related stigma, number of siblings/children living in household, lower social support, lower household size, lower socioeconomic status and not presently attending school [14,20]. Just as shown in previous research, this finding indicates that RAD symptoms may be as a result of mainly environmental factors [9,15,25].

Finally, with regard to the fourth aim to investigate any interactive, cumulative effects between the aetiological or contextual factors (both risks and protective) for higher RAD symptoms, the results highlighted the interactive and cumulative effects of identified risks and protective factors for RAD symptoms. The results demonstrated strong interaction effects between neglect, psychological abuse, stigma and orphanhood status for heightened RAD symptoms among OVC. Experiencing of more neglect and more psychological abuse increased the risks for symptoms of RAD from 26.6% to 67.3%. Similarly, experience of neglect and living with HIV/AIDS-infected parents increased the likelihood of RAD symptoms five-fold. Furthermore, experiencing neglect heightened the proportion of likely RAD symptoms three-fold for children orphaned by AIDS and orphans of other causes. Consistently RAD is thought to be associated with maltreatment in the literature [19,21] and in the ICD-10 & DSM-IV psychiatric classification systems [12,13]. These findings indicate that compared with non-orphans, OVC affected by HIV/AIDS form a vulnerable group for RAD symptoms. Specifically, children who are living with HIV/AIDS-infected parents and are often psychologically abused and neglected are at the highest risk for RAD symptoms. This finding demonstrates that abuse and neglect may be more important than orphanhood per se for RAD symptoms.

Implications of the results

The results of this study demonstrate that reactive attachment disorders are present in children affected by HIV/AIDS. This study also demonstrates the high levels of comorbidity with other disorders including depression and conduct problems. This has implications for the assessment, intervention, and education of this group of children when they present with difficulties.

The important clinical implications of the findings for service delivery, as noted by Pritchett et al. [21], is that aspects of the RAD presentation such as indiscriminate friendliness may be overlooked in a child who presents from children affected by HIV/AIDS. This has potential implications for targeting the most appropriate and effective intervention for the child especially as there is lack of awareness of RAD presenting within these children.

The findings underscore the need to reach out to the caregivers of OVC considering that children with RAD may develop into peer relationship difficulties and disruptive behavioural disorders in later years. Caregivers of OVC with RAD symptoms may have a special challenge providing the appropriate warm and tender care as these children may be unwilling to receive it. For the OVC that are presently in school, this may be problematic for teachers as these children who have RAD symptoms may not be easily identifiable and may therefore not be considered in an “at risk” group. These caregivers and teachers must be well trained and well-resourced/supported to strengthen their caregiving capabilities to deliver in respect. It is particularly important that teachers encourage OVC to feel a part of the class and the wider school community with inclusion being even more vital for those neglected or abused. There is also the urgency to develop community interventions that address both specific risk factors of HIV/AIDS (e.g. stigma) and contextual risk factors (such as socio-economic provisions, educational support systems, family/community support networks, alleviation of child labour and child maltreatment) within which children affected by HIV/AIDS find themselves. Such interventions, it is suggested will effectively alleviate these risks factors and enhance the mental health of children.

Conclusion

This is the first study to demonstrate that children affected by HIV/ AIDS in the community, are at heightened risk for psychiatric disorders including RAD and that experiencing more neglect and psychological abuse among OVC increases the likelihood of RAD symptoms five-fold. This is interesting because most previous research on RAD has been in institutionalized samples [9,10,11,12,25]. Future research should examine whether RAD symptoms precede and are a risk factor for other mental health problems or whether comorbidity between RAD and other mental health problems is common in children affected by HIV/AIDS.

Authors’ Contributions

PND designed, conducted and drafted the study under the supervision of HM. Both PND and HM read, edited and approved the manuscript for submission.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the Glasgow-Strathclyde Universities Scholarships and the Overseas Research Scholarship for sponsoring the studies, the Parkes Foundation and Brian Rae, former NHS Manager, Glasgow for funding the research fieldwork project. Prof. Brae, God bless you for the unmerited help.

References

- Cluver L, Gardner F, Operario D (2007) Psychological distress amongst AIDS-orphaned children in urban South Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 48: 755-763.

- Doku PN (2010) Psychosocial adjustment of children affected by HIV/AIDS in Ghana. J Child AdolescMent Health 22: 25-34.

- Doku PN (2009) Parental HIV/AIDS status and death, and children's psychological wellbeing. Int J Ment Health Syst 3: 26.

- He Z,Ji C (2007) Nutritional status, psychological wellbeing and the quality of life of AIDS orphans in rural Henan Province, China. Trop Med Int Health 12:1180-1190.

- Nyamukapa C, Gregson S, Lopman B, Saito S, Watts, et al. (2008) HIV-associated orphanhood and children’s psychological distress: Theoretical framework tested with data from Zimbabwe. Am J Public Health, 98:133-141.

- Rotheram-Borus M J,WeissR, Alber S, Lester P (2005) Adolescent Adjustment Before and After HIV-related Parental Death. J Consult ClinPsychol73: 221-228.

- Doku PN, Dotse JE, Mensah KA (2015) Perceived social support disparities among children affected by HIV/AIDS in Ghana: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 15: 538.

- Zeanah CH, Gleason MM(2015) Annual research review: attachment disorders in early childhood – clinical presentation, causes, correlates and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry56: 207 -222.

- Gleason MM, Fox NA, Drury S , SmykeA, Egger HL, et al. (2011) Validity of evidence-derived criteria for reactive attachment disorder: indiscriminately social/disinhibited and emotionally withdrawn/inhibited types. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50: 216-231.

- Minnis H, Green J, O’Connor T, Liew A, Glaser D, et al. (2009) An exploratory study of the association between reactive attachment disorder and attachment narratives in early school-age children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 50: 931-942.

- Skovgaard AM (2010) Mental health problems and psychopathology in infancy and early childhood. An epidemiological study. Dan Med Bull 57: B4193.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (5th edn.) American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.

- World Health Organization (2002) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva 2002: World Health Organisation.

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, et al. (2009) Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373: 68-81.

- Minnis H, Macmillan S, Pritchett R, Young D, Wallace B, et al. (2013) Prevalence of reactive attachment disorder in a deprived population. Br J Psychiatry 202: 342-346.

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Fox NA, et al. (2012) A randomized controlled trial comparing foster care and institutional care for children with signs of reactive attachment disorder. Am J Psychiatry 169: 508-514.

- Hornor G (2008) Reactive attachment disorder. J Pediatr Health Care 22: 234-239.

- Minnis H, Rabe-Hesketh S,Wolkind S (2002) A brief, clinically effective scale for measuring attachment disorders. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 11: 90-98.

- Millward R, Kennedy E, Towlson K, Minnis H (2006) Reactive attachment disorder in looked-after children, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 11:273-279.

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Carlson E (2005) Bucharest Early Intervention Project Core Group Attachment in institutionalized and community children in Romania. Child Dev 76: 1015-1028.

- Pritchett R, Pritchett J, Marshall E, Davidson C, Minnis H (2013) Reactive Attachment Disorder in the General Population: A Hidden ESSENCE Disorder.

- Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40: 1337-1345.

- Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V (2003) The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Int Rev Psychiatry 15: 173-177.

- Minnis H, Pelosi AJ, Knapp M, Dunn J (2001) Mental health and foster carer training. Arch Dis Child 84: 302-306.

- Minnis H, Reekie J, Young D, O'Connor T, Ronald A, et al. (2007) Genetic, environmental and gender influences on attachment disorder behaviours. Br J Psychiatry 190: 490-495.

- Boris N, Thurman T, Snider L, Spencer E, Brown L (2006) Infants and young children living in Youth-headed households in Rwanda: Implications of emerging data. Infant mental health journal: Culture and Infancy special issue 27: 584-602.

- Gershoff ET (2002) Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull 128: 539-579.

- Budlender D, Bosch D (2002) South Africa Child Domestic Workers: A National Report. Geneva International LabourOrganisation. Internationalprogramme on the elimination of child labour.

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment 52: 30-41.

- Lopman B, Cook A, Smith J, Chawira G, Urassa M, et al. (2010) Verbal autopsy can consistently measure AIDS mortality: a validation study in Tanzania and Zimbabwe. J Epidemiol Community Health 64: 330-334.

- Thomas F (2006) Stigma, fatigue and social breakdown: exploring the impacts of HIV/AIDS on patient and carer well-being in the Caprivi Region, Namibia. SocSci Med 63: 3174-3187.

- Minnis H, Fleming G, Cooper S (2010) Reactive Attachment Disorder Symptoms in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 23: 398-403.

- Hanson RF, Spratt EG (2000) Reactive Attachment Disorder: what we know about the disorder and implications for treatment. Child Maltreat 5: 137-145.

- Rushton A, Minnis H (2002) Residential and foster family care, in: Rutter M, Taylor E,Hersov L.Child and adolescent psychiatry: modern approaches.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14364

- [From(publication date):

February-2016 - Apr 21, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 13216

- PDF downloads : 1148