Research Article Open Access

Qualitative Assessment of Community Education Needs: A Guide for an Educational Program that Promotes Emergency Referral Service Utilization in Ghana

Olokunde TL1, Awoonor-Williams J2,3,4*, Tiah JAY2, Alirigia R2, Asuru R2, Patel S1, Schmitt M1 and Philips JF11Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, NYC, NY, USA

2Ghana Health Service, Upper East Region, Ghana

3Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute Socinstrasse 57 4002 Basel, Switzerland

4University of Basel, Peterplatz 4003, Basel, Switzerland

- *Corresponding Author:

- Awoonor-Williams J

Ghana Health Service

Upper East Region, Ghana

Tel: +233208161394

E-mail: kawoonor@gmail.com

Received Date: July 28, 2015 Accepted Date: August 18, 2015 Published Date: August 23, 2015

Citation: Olokunde TL, Awoonor-Williams J, Tiah JAY, Alirigia R, Asuru R, et al. (2015) Qualitative Assessment of Community Education Needs:A Guide for an Educational Program that Promotes Emergency Referral Service Utilization in Ghana. J Community Med Health Educ 5:363. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000363

Copyright: © 2015 Olokunde TL, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: Ghana has a maternal mortality ratio of 380/100,000 live births and a neonatal mortality rate of 28/1,000 live births. Although most of these deaths could be prevented by timely access to quality care during medical emergencies, the country lacks a functional emergency referral care system. To test feasible means of addressing this need, the Sustainable Emergency Referral Care (SERC) Initiative was piloted in the Upper East Region of Ghana.

Objectives: This study was conducted to understand the role of and need for knowledge about emergencies on the utilization of emergency referral services in study setting. It describes community members’ ability to recognize and respond to signs of obstetric and neonatal emergencies with the goal of eliciting potential strategies for an effective community education component of the SERC program.

Methods: Seven focus group discussions were conducted among homogenous groups of community members in three districts. All discussions were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim, coded in NVivo 10.2 software and analyzed using framework analysis.

Results: Most respondents recognized emergencies as life threatening conditions that require urgent intervention but there were varying views about emergency types and the appropriate responses for each type. Some emergencies were considered to be “frafra issues”, which meant traditional issues peculiar to a specific tribe. Such misconceptions, certain cultural practices and social dynamics that influence the decision to seek and utilize referral services were elicited.

Conclusion: There were clearly mistaken beliefs and detrimental practices that merit specific focus in an educational program. For instance: the perceptions of certain emergencies as traditional or spiritual problems and consequently seeking spiritual, rather than medical, treatments for those, needed to be addressed. Dialogue generated practical recommendations for developing the content of educational materials and improving the appropriate utilization of emergency services.

Keywords

Northern Ghana; Community education; Emergency referral care; Qualitative study; Obstetric emergencies; Childhood emergencies; Medical emergency; Emergency transportation

Background

The problem

About 800 mothers die every day from preventable causes associated with pregnancy or delivery. 99% of these deaths occur in developing countries [1]. According to United Nations estimates, 6.3 million of the world’s children below five years of age died in 2013, but the risk of dying is 15 times higher for children living in Sub-Saharan Africa than in developed regions. Neonatal deaths account for about 44% of these deaths [2]. Ghana exemplifies this climate of maternal and childhood risk: Its maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is 380 maternal deaths/100,000 live births [3] and its neonatal mortality rate (NMR) is 28/1,000 live births [4]. Although most of these deaths could be prevented if timely quality medical care were available during medical emergencies, Ghana lacks a functional emergency referral care system [5]. This challenge is particularly evident in the Upper East Region (UER), which is not only one of the most impoverished regions in the country but where access to essential care is constrained by poor road networks, difficult terrains and harsh weather conditions. Common emergency transportation options available in the region are foot, bicycles, donkey carts and motorbikes [6]. These inadequate means of transport, in addition to poor communication systems for emergency response, incur untenable delays in reaching care when emergencies arise. In order to address this need, the Sustainable Emergency Referral Care (SERC) Initiative was launched in 12 rural sub-districts of the Upper East Region (UER) of Ghana in 2013 [7].

The intervention

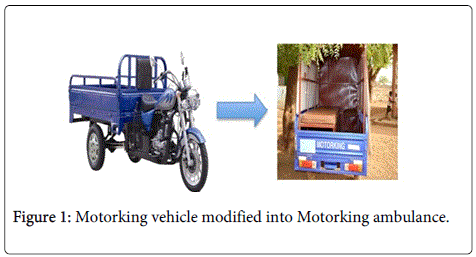

Local three-wheeled vehicles, locally called “Motorkings”, were modified into special ambulances and placed at strategic stations within the communities (Figure 1). Although they do not resemble conventional ambulance, they were found to be suitable on rough terrains during a preliminary plausibility trial. In order to facilitate communication and coordinate Motorking utilization during emergencies, mobile phones were provided to community health workers at the Motorking stations, to volunteer drivers and to community health volunteers in non-Motorking stations.

The SERC initiative is part of a larger health systems strengthening initiative known as The Ghana Essential Health Interventions Program (GEHIP). A collaborative team of researchers and health workers from the Ghana Health Service (GHS) and the Mailman School of Public Health (MSPH) developed GEHIP. GEHIP seeks to add missing interventions to the GHS’s primary health care program; provide training and technical assistance to strengthen the capacity of the leadership; and provide support to health system structures in order to enhance their effectiveness, especially at community level [6]. SERC is the core strategy that GEHIP employs to address the need for an intervention focused on the overall goal of reducing the second level of delay [7], as described by Maine and Thaddeus [8]. Three levels of delay have been identified as critical points for emergency obstetric care interventions: i) delay in seeking medical care, ii) delay in arriving at a health facility, and iii) delay in receiving quality care at the health facility [7].

Although the second level of delay is a well-documented and apparent barrier to utilizing and benefiting from emergency medical services [9-13], the first level delay is also of paramount significance in most rural settings in Sub-Saharan Africa [9,14,15]. Timyan et al. highlighted the role of informational barriers to health services utilization as a cause of the first level delay [16], attesting to the need to provide information for encouraging the utilization of emergency referral services thereby reducing first level delay.

The implementation gap

Community members usually play a key role in initiating the first step in the process of emergency referral due to their influence on decision-making. Hence, they need to be able to promptly identify signs of emergencies and facilitate decision to seek medical care [17]. At the time of this study, a community education component to address information barriers was yet to be formalized as part of SERC. This implementation gap, together with documentation indicating low utilization of SERC services, motivated the development of a community education program (CEP).

Study objectives and significance

This qualitative study sought to describe community members’ ability to recognize and respond to signs of medical emergencies — particularly obstetric and neonatal emergencies, and to elicit community education strategies that would be effective to address knowledge gaps identified. Findings were to guide the development of SERC’s CEP. Several studies have revealed poor knowledge about signs of obstetric, neonatal and other medical emergencies among community members in rural parts of developing countries [18-25]. However, some studies have also reported good knowledge of these signs in similar settings [26]. While some authors have shown a positive influence of increased knowledge of these signs on health seeking decisions and actual utilization of medical services [15,27], other studies could not provide sufficient evidence to show a significant relationship between knowledge of signs and service utilization [28]. The variation in research findings across studies done in similar settings is a warrant for this study. Different findings have been documented within Northern Ghana where SERC operates. Although a study by Aborigo et al. demonstrated that rural community members have knowledge of a wide range of obstetric danger signs [26], Yidana et al. showed that most women in another rural district exhibited poor knowledge of danger signs and complications associated with pregnancy [29].

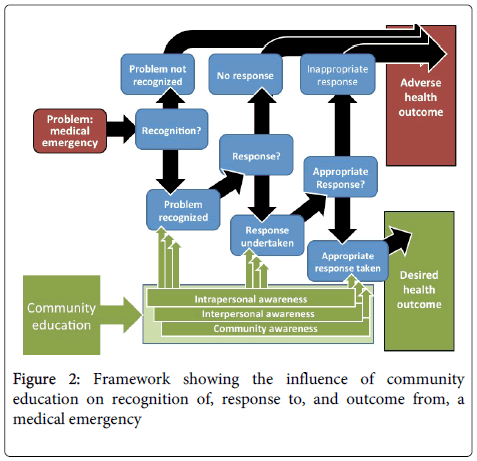

This study was pursued to clarify the context in which SERC operates, in terms of knowledge of obstetric and neonatal complications and how these influence utilization of referral services. Pathways for decision-making and the possible impact of community education are specified in Figure 2. The study also sought to elicit potential effective strategies to be implemented within SERC. Highlights of this paper include (i) employing theory to understand problem and analyse data; and (ii) generating data to inform action by identifying acceptable and contextual strategies that can address the gaps which the study identifies.

Conceptual framework

A conceptual framework was synthesized from two models and a theory, and grounded in relevant evidence, to improve understanding of the role of community education in the SERC implementation framework. They are i) the extended parallel process model (EPPM), ii) the communication theory and iii) the ecological model [30]. These were deemed to be appropriate for exploring relationships implied by our data.

The EPPM describes two main concepts: threat and efficacy. The first concept describes perceived susceptibility and perceived severity while the second describes response efficacy and self-efficacy [30]. Recognition of medical emergencies speaks to the perception of the threat that the condition poses; whether or not it is considered life threatening; and whether an adverse outcome is considered imminent without medical intervention. On the other hand, response to emergencies is a function of the perceived effectiveness of available services and the perception of their ability to use the appropriate services in emergency situations. Evidence shows that perceived threat is linked with response efficacy. For instance, Dako-Gyeke et al. showed that beliefs, perceptions and knowledge about threats associated with pregnancy and delivery influenced utilization of services, hence, expected to affect outcome [31]. EPPM has been successfully used to demonstrate how perceived threat and efficacy influences the intention and behaviour of physicians to utilize laboratory services [32].

The Communication theory seeks to address questions such as ‘Who says what? Through which channels should education be delivered? To whom should education be targeted? When and how often? And, with what effects?’ [30]. It is therefore appropriate for exploring the recommended strategies for community education. While EPPM and the Communication theory facilitate understanding of the education needs and strategies, the ecological model facilitates explanation of the different levels of influence that can modify those needs and recommendations [30]. The intra-personal and inter-personal characteristics of a person and their social networks, respectively, such as their personality traits; knowledge; perceptions; and efficacy influence the way emergencies are perceived and addressed. The environmental levels of influence, such as cultural norms; community resources; and relevant policies also determine responses to emergencies. Each level cannot solely influence perception and response to emergencies, rather interactions across levels to produce behaviors [30].

The logic model posits a linear relationship starting with the problem — medical emergency — to a potential outcome. The framework illustrates how the three main levels of influence of the ecological model interact with other variables to modify the outcome. This can be supported by evidence that cultural and socio-economic barriers interact in ways that profoundly influence the utilization of health services for obstetric complications around the world [33].

Community education strategies may target any one or combinations of the three levels of influence, and through these levels modify people’s ability to recognize and respond to emergencies. Udofia et al. discussed how the awareness of danger signs of obstetric, neonatal and childhood emergencies play a significant role in how community members respond to emergencies [34]. Opoku et al. have described the positive impacts of community education on utilization of emergency obstetric services in Ghana [18]; as utilization increased, positive outcomes of emergencies increased and utilization improved.

Evidence consistently shows that the quality of emergency care services affects health outcomes and health service utilization [35]. Quality services can also impact on the effectiveness of community education activities through confidence levels in the health system. However, this framework does not feature the functionality of health facilities and its relationship with other variables in the model because that is outside the scope of this study.

Methods

Data were collected through seven focus groups conducted in June 2014 among homogenous groups of community members in SERC’s implementation districts in Ghana’s Upper East Region. Groups comprised of pregnant women and mothers of infants; male household heads; and grandmothers. All discussions were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim, coded using NVivo 10.1.2 software and analysed using framework analysis. Informed consent was received from each participant and participants were compensated for their time. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Columbia University and the Navrongo Health Research Centre Institutional Review Board (NHRCIRB) reviewed and approved the study.

Study setting

The study was conducted among selected rural communities of three districts with an estimated total population of about 123, 750 people. Purposive sampling was used to select the six study sites; communities where the Motorking stations are situated were selected as these stations serve neighbouring communities. Community health officers and volunteers directly recruited ten to twelve community members to participate in the discussions. Discussions lasted 60-90 minutes and were facilitated in the local languages by two male moderators who were native speakers of the local language of their assigned district and were trained in qualitative data collection. The moderators also translated the semi-structured FGD guide to the local languages and three research assistants transcribed the audio-recorded discussions into English.

The analytical approach

The qualitative data were analysed using framework analysis. The main themes in the conceptual framework displayed in Figure 2 above were used to develop the codebook. The codebook included succinct definitions of each code; notes on when to use and not use each code; and examples of correct application of codes. Examples of incorrectly applied, but likely, codes were also included. Using version 10.1.2 of NVivo software, the data were labelled appropriately with codes and labelled data were organized into conceptually ordered and checklist type matrices.

Reliability and validity of instruments and procedures

The semi-structured FGD guide was reviewed with the local SERC team and translators for cultural appropriateness and clarity in order to increase internal validity. The FGD guide was translated without back translation a procedural problem that may compromise the internal validity and reliability of the study. A pre-test FGD was conducted among rural community women in one of the districts. The recorded pre-test discussion was transcribed for review before conducting the main FGDs, to ensure that discussion was focused as desired and that participants’ responses demonstrated sound understanding of questions.

Respondents were recruited from the communities in which SERC services had been launched, hence a threat to external validity of the study. Participants’ responses, thus findings, may be dissimilar if FGDs were conducted in communities without access to the services.

Results

A total of 76 community members participated and they were asked about their general perception of emergencies; whether they thought members of their communities were able to recognize signs of medical emergencies; how decisions to seek care are usually made; and factors that influence care-seeking decisions. They were also asked how they would implement an effective educational program on emergency signs for their communities. Although obstetric and childhood emergency signs were the primary concern of this study, discussions around general medical emergencies were also facilitated to minimize the influence of social desirability on the data. Themes that emerged from discussions with their supporting quotes are tabulated below, and highlighted thus:

Recognition of emergencies

Participants’ descriptions of emergencies were mostly correct, although incorrect and unclear accounts existed. Emergencies appeared to be categorized into types such as medical conditions and traditional problems; one participant classified a particular type of emergency as ‘frafra issues’, which meant peculiar traditional issues. However, the discussion about emergencies was mainly around the perception of severity relating to a condition, regardless of their classifications and whether or not their descriptions of conditions were correct. The following quote portrays this.

Probe: Why do you think malaria is an emergency?...

Male respondent: I say this because it can kill faster especially in young children. (Direct quote).

The discussions also touched on efficacy. Most participants thought that community members either possess the ability to recognize emergency signs or the ability to learn how to recognize them. They made reference to acquiring knowledge and skills for such recognition. A male respondent said:

If they see someone in an emergency they can make reference to the teachings of the health workers and identify the emergency. (Typos edited).

A few participants, however, expressed doubt about people’s capacity to recognize emergencies. Additionally, many participants described how recognition of emergencies guided individual and/or corporate actions during medical emergencies.

Decision to respond to emergencies

Many participants described their capacity to make decisions in response to emergencies in terms of perceived severity and self-efficacy. They also discussed the various actors in the communities and households who play a role in shaping decisions to respond to emergencies and when these are made; whether promptly or delayed. A young mother noted:

When there is an emergency and I see that my baby’s body is very hot. I can decide myself to send the child to the health facility. (Direct quote)

Actual response

Participants described how threats arising from emergencies drive response to utilize emergency services, or otherwise. They also discussed their response to emergencies as it relates to individual or community level knowledge, skills or attitude around emergencies. They described actions, or practices, that are related to the response to seek medical care, or not, during emergencies. Some of these actions reflect timeliness of response; delay is an important theme that emerged.

Outcome

Participants described their motivation for responding to emergency in light of the threat posed by the emergency, their response being aimed at favourably modifying health outcomes. Most of them expect the utilization of the emergency services to convert fatal outcomes to good ones. Thus they discussed actions they carry out to modify the outcomes of emergencies. A man advised thus:

If your child is having a headache and his body is very hot and you can get to the doctor, get there quick… five minutes can kill a person (Direct quote)

Discussion suggested that respondents did not think their personal knowledge and skill could modify outcome of emergencies directly. Some respondents were fatalistic believing that outcomes could only be modified to the extent that the type of emergency allows. This quote highlights this belief.

I have seen that there is a certain emergency sickness if you are there the sickness is (local name) in frafra (local culture) they call it (local name) if it gets you, you have to get leaves for them to be drinking and if you send it to the doctor, that one, it doesn’t want injection. If the doctors don’t know and use the injection it will lead to death (Grandmothers; edited for clarity)

Recommendation on education message

Participants recommended ways that the message about emergency signs could be presented. They include use of examples, case studies, explanations and severity (threat). They also discussed the use of community education to correct misconceptions about emergencies and response to them.

Channel for education delivery

Various media through which effective community education can be carried out were elicited and they included use of radio jingles, illustrations, mobile announcement vans and videos. See quotes in table 1.

| Categories | Themes | Quotes |

| Recognition of emergencies | Threat: Perception of severity | The high fever is one of the diseases that can easily kill. The person behaves insane and can hit himself against things and dies [Men] |

| Cerebrospinal Meningitis… There were some who died and the lucky ones survived [PWMI [1]] | ||

| Self-efficacy for recognition | I feel that those community members who can really detect the signs of emergency are very few. [PWMI] | |

| It is not all the emergencies that the community members know the signs and can tell. I feel that just few people can tell what emergency signs. [Men] | ||

| Decision to respond to emergencies | Efficacy for recognition | I have been taught the signs of danger in children…If there is no one at home I will go to the hospital without waiting for permission. If they are there but do not give me the permission to go, I would have to disobey them and go. [PWMI] |

| Actors in households and communities | We also have some women in the community who help women deliver (TBAs). They monitor the labor and assess if it is time for the woman to deliver. If she cannot help the woman to deliver. She will come to the health facility to inform them that there is a woman who is finding it difficult to deliver. We will then make request for them to allow the Motorking send the woman to (health facility name) [Men] | |

| When there is an emergency, it is the house head who gives the go ahead for the person to be sent to the health facility. If it is my wife who is the victim of the emergency, I have to give the go ahead before they can go to the health facility. [Men] | ||

| Actual response to emergencies | Threat leads to actual desired response | Cholera affected someone and we had to rush the person to the hospital because we felt that he could die. [Men] |

| Actions or practices influence timeliness of response | They normally send the person to the soothsayer first. When they return they will pour libation. When they realize that the victim is complaining of so much pain they will then send the person to the health facility. When they know that the spiritual solution in not working they will then go to the hospital. [Men] | |

| Outcome or Expectations from response | Belief in the outcomes associated with utilizing services influence behavior | If I hear emergency sickness I have to hurry up and get to doctor and see what made the sickness to do that for him to save us”[Grandmothers] |

| Type of emergency determines outcome from utilizing medical services | Cerebrospinal Meningitis… There were some who died and the lucky ones survived…Some people died immediately the ambulance arrived to send them to the hospital. [PWMI] | |

| Recommendations about education messages | Use examples, case studies and explanations | Apart from (mentioning) the signs, I will give (an) example (of a scenario) [PWMI] |

| Highlight threats | I will emphasize that it is one of the diseases that can easily kill an individual. [PWMI] | |

| Correct misconceptions | I will tell them the practice of waiting to make spiritual consultation before sending laboring pregnant women to the health facility to deliver is past so all should try to deliver at a health facility. [Men] | |

| Channels of education delivery | Announcements using mobile vans, radio jingles | I will use the information van. [Men] |

| Use of illustrations; pictorial presentations | I will show them pictures of the signs of some of the diseases considered emergencies. [PWMI] | |

| Use of videos | The health workers could come along with video clips of some of the emergencies signs to show to the participants. [PWMI] | |

| Discussions, lectures and word of mouth | Anywhere two or three people are gathered including market places, the message will be said to them. We will tell them about health emergencies and how to detect them. At traditional dance and entertainment, we can also teach them. [Men] | |

| We go from house to house to disseminate information or stand on top of the roof and call the name of the nearest house. If someone responds then we will pass on the information. But if the message is long then we have to walk to the house. [Grandmothers] | ||

| Facilitator characteristics | Who should be eligible? | I agree with (R1) that the health workers should be included. [PWMI] |

| Credible community member or professional | If I want to do this, I will include the health workers that the communities are aware of… if the people get to know that the health workers are involved in it, they will come in their numbers. [PWMI] | |

| Desirable personality | There is the need for the presenter to be calm and friendly to the attendants… If you are friendly, like you started cracking jokes and we all laughed before starting, the people will be attentive to listen. [Grandmothers] | |

| Undesirable characteristics | If you are someone who is not sociable to the people then they will not listen to you. [Grandmothers] | |

| The process | Gatekeepers | Before the meeting can be held, there is the need to first brief the chief what it is that will be discussed at the meeting. We will then ask him to send a message to the various household heads to tell their house members to attend the meeting that the whole community will be attending. [Men] |

| Considerations about timing and frequency | We also do communal farming. During these activities, we can also educate, share with them the signs of emergencies when we break to rest. This is the rainy season and we are most likely to meet ourselves including the elderly during communal farming. [Men] | |

| To enhance their understanding, the meeting should not be once. It could be repeated after two weeks to see if they understood what was taught... If the meeting is done once and not repeated the people will forget. [Grandmothers] | ||

| PWMI: Pregnant women and mothers of infants [1] |

Table 1: Results showing themes and quotes.

Facilitator characteristics

Participants discussed the attributes or characteristics that the person who will deliver the message should have in order to ensure effective communication, and discouraged the use of certain facilitators for community education. They noted that the facilitator should be a credible health professional or community member, and one who is tolerant, respectful and funny.

If I call the whole community at a meeting to do this presentation to them they will ask that since when I became a nurse to teach them of signs of emergencies. If you want to call people to a place and tell them of signs of emergencies, they will say, “What do you even know about emergencies and want to share with us”. [PWMI; Direct quote].

The process

Participants elaborately provided insight into the processes and considerations that should be carried out for effective community education.

Before that can happen, the chief has to be informed. He will then also call all the house heads in the community and inform them about the presentation. You will then educate the house heads first and the chief before the community’s education. [PWMI; Direct quote].

Discussion

The data provided insight into how community members recognize and respond to emergencies, and their advice on appropriate strategies for developing educational materials for an effective community education. The conceptual framework applied was appropriate for analysis. Responses suggest that there were no important difference between the three participating groups; responses did not differ based on gender or age of participants. Participants described their recognition of emergencies in terms of their perceived severity. Community members labelled health conditions as emergencies based on how they perceived its severity and their susceptibility to it or a related adverse outcome. Most medical conditions that were correctly identified as emergencies were perceived so because they threaten a person’s life. Respondents varied in their perception of susceptibility to emergencies: while most participants understood that emergencies are usually sudden and unpredictable, a few thought that some individuals are particularly more susceptible than others. Generally, these perceptions informed the way people responded to emergencies. Thus, discussions about responses to emergencies revolved around perceived efficacy. For example, a participant, talking about obstetric complications, mentioned how some particular women are susceptible to complications that threaten their lives and how caesarean section is the only way they can be saved, suggesting that such women should utilize emergency services in order to avert death. It appeared that some community members might respond differently to warning or danger signs of an emergency depending on whether or not they perceive themselves, or those around them, to be susceptible to the emergency or its potential impact.

The link between recognition and response, as displayed in the conceptual framework (Figure 2), demonstrates a relationship that should be considered for developing educational materials and programs. An effective educational material would need to facilitate an understanding of susceptibility to, and also severity of, medical emergencies in order to stimulate self-efficacy in terms of promptly deciding to seek care and utilizing the emergency referral services. There is evidence to support the notion that perceived threat motivates behaviour change starting with a changed attitude. A study, which investigated how distance affected the utilization of health services in rural Nigeria, showed that utilization of health services was closely tied to people’s perception of the threat of a particular disease as well as to their perception of the effectiveness of the available health services [36].

Another finding from this study is that participants thought that community members either have the ability to recognize or to learn to recognize emergency signs. They made reference to acquiring knowledge and skills for such recognition, which is positive self-efficacy. A few participants expressed doubt about people’s capacity to recognize emergencies. This provides a background for understanding the community members’ attitude to education for improving their capacity to recognize and respond to emergencies. Overall, findings lend support to policies calling for educational messages and activities that will increase knowledge, and required for enhancing prompt decisions about emergency medical care. The concern of the minority of participants, who doubt the ability of lay men to acquire knowledge and skills for recognizing emergency signs, should also be addressed by designing an easy-to-understand and easy-to-remember educational messages.

Lastly, recommendations generated by participants covered the aspects required to develop culturally relevant educational materials and addressed all the guiding questions of the communication theory. Their responses were useful for guiding the content and scope of an educational curriculum. For instance, they suggested that misconceptions should be addressed. Such misconceptions include perception of certain emergencies as traditional or spiritual problems and consequently seeking spiritual treatments, rather than medical attention, for those. Some others are claims that certain interventions like caesarean sections were for certain weak women or that medical treatments of certain emergencies worsen the problem, or even lead to death. Yidana’s findings, that educational messages can nudge community members to modify traditional practices, support this suggestion [37]. Respondents suggested the use of narratives in the form of case studies and live stories, or testimonies, in conveying educational messages. They desired thorough explanations through fun channels such as radio jingles, illustrations, mobile announcement vans and videos. Some of their desired attributes for persons who would facilitate educational activities were friendliness, patience, respect from the community, and skill in the subject. Study participants also provided information about important gatekeepers and community protocols needed for an effective community education program.

Application of Findings

This study fostered partnership of stakeholders at the districts with those at community levels. Guided by study findings, educational messages were created in form of stories, lyrics and concepts for illustrations. These messages were transformed into educational materials including jingles, videos, posters and flip charts, which were field-tested and used for SERC’s education program. The educational program developed is expected to improve how community members define problems related to medical emergencies and empower them to become more active in managing emergency conditions within their families and communities. Ciccone et al. view that people are central to defining their health-related problems, which enables them to comply with treatment options and maintain continuous relationships in health care, supports this expectation [38]. They also noted that a program that informs and involves patients empowers them to solve problems, be confident and gain self-efficacy [39].

Limitations

All analytical steps were logically reasonable and justifiable within the context of the study objectives and conceptual framework. One major limitation of this study is purposive sampling of participants from communities where the emergency referral service interventions are situated. Participants who seemed to demonstrate a sound understanding of an emergency might not be true representatives of their districts. They might have been exposed to information about emergencies by virtue of their proximity to intervention stations. This might have a negative impact on the materials that will be developed for use in many other communities where the Motorking is not stationed.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to express special gratitude to the community members who participated in the study; the community leaders and their people who supported them; and the members of the district health management teams who recruited participants and hosted discussions. A special thanks is expressed to funders of the Ghana Health Intervention Program (GEHIP) and the Sustainable Emergency Referral Care (SERC): The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and Comic Relief UK. Godwin Tamakloe; Dominic Achinkok; Margaret Azure; Winnard Agbeko; Mathias Adoba and the entire GEHIP team are thanked for their immense field and logistical support.

Conclusion

Community members who participated in this study mostly recognized emergencies as life threatening conditions that require urgent intervention but there were varying views about emergency types and the appropriate responses for each type. Misconceived views remarkably influence the decision to seek and utilize medical referral services, which culminate in avoidable delays. Other misconceptions were about susceptibility to emergencies and self-efficacy to identify signs of emergencies. Cultural practices and social dynamics also emerged as strong determinants of the decision to utilize emergency referral services.

Clearly, there were mistaken beliefs and practices that merit specific focus in an educational program. Recommendations elicited for developing such a program were practical; they were context-specific, focused on all parties involved in decision-making, and included delivery methods that have the potential to address misconceptions in a non-threatening manner. SERC community education program has been developed and tailored accordingly using these findings. Similar research should be conducted in other locations in order to tailor education programs to the context and needs of the target population.

References

- World Health Organization (2014) Maternal mortality: to improve maternal health, barriers that limit access to quality maternal health services must be identified and addressed at all levels of the health system: fact sheet.

- World Health Organization (2014) Children: reducing mortality.

- World Health Organization (2014) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Countdown to 2015. Maternal, Newborn & Child Survival (2014) Fulfilling the Health Agenda for Women and Children: The 2014 Report.

- Hussein J, Kanguru L, Astin M, Munjanja S (2012) The effectiveness of emergency obstetric referral interventions in developing country settings: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine 9: e1001264.

- Awoonor-Williams JK, Bawah AA, Nyonator FK, Asuru R, Oduro A, et al. (2013) The Ghana Essential Health Interventions Program: a plausibility trial of the impact of health systems strengthening on maternal & child survival. BMC Health Services Research 13: S3.

- Helibrunn Department of Population and Family Health. “Sustainable Emergency Referral Care Initiative.” Advancing Research on Comprehensive Health Systems.

- Thaddeus S, Maine M (1994) Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Social Science & Medicine 38: 1091-1110.

- Maine D, Rosenfield A (1999) The Safe Motherhood Initiative: why has it stalled? American Journal of Public Health 89: 480-482.

- Gabrysch S, Cousens S, Cox J, Campbell OMR (2011) The influence of distance and level of care on delivery place in rural Zambia: a study of linked national data in a geographic information system. PLoS Medicine 8: e1000394.

- Kitui J, Lewis S, Davey G (2013) Factors influencing place of delivery for women in Kenya: an analysis of the Kenya demographic and health survey, 2008/2009. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 13: 40.

- Wilson A, Hillman S, Rosato M, Skelton J, Costello A, et al. (2013) A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on maternal emergency transport in low-and middle-income countries. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 122: 192-201.

- Munjanja SP, Magure T, Kandawasvika G (2012) Geographical Access, Transport and Referral Systems. In: Maternal and Perinatal Health in Developing Countries 139.

- Gazmararian JA, Dalmida SA, Merino Y, Blake S, Thompson W, et al. (2014) What New Mothers Need to Know: Perspectives from Women and Providers in Georgia. Maternal and Child Health Journal 18: 839-851.

- Doctor HV, Findley SE, Cometto G, Afenyadu GY (2013) Awareness of Critical Danger Signs of Pregnancy and Delivery, Preparations for Delivery, and Utilization of Skilled Birth attendants in Nigeria. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 24: 152-170.

- Timyan J, Griffey Brechin SJ, Measham DM, Ogunleye B (1993) Access to care: more than a problem of distance 217-234. In: The health of women: a global perspective. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado.

- Susan FM, Pearson SC (2006) Maternity Referral Systems in Developing Countries: Current knowledge and future research needs. Social Science & Medicine 62: 2205-2215.

- Opoku SA, Kyei-Faried S, Twum S, Djan JO, Browne ENL, et al. (1997) Community education to improve utilization of emergency obstetric services in Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 59: S201-S207.

- Hailu D, Berhe H (2014) Knowledge about obstetric danger signs and associated factors among mothers in Tsegedie district, Tigray region, Ethiopia 2013: Community based cross-sectional study. PloS One 9: e83459.

- George SO, Yisa IO, Alawode G (2014) Knowledge of obstetric danger signs amongst women of reproductive age in paths2 Zaria cluster, Kaduna Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine 23: 26-32.

- Hoque M, Hoque ME (2011) Knowledge of Danger Signs for Major Obstetric Complications Among Pregnant KwaZulu-Natal Women Implications for Health Education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 23: 946-956.

- Dunn A, Haque S, Innes M (2011) Rural Kenyan men’s awareness of danger signs of obstetric complications. Pan African Medical Journal 10: 39.

- Mesay H, Gebremariam A, Alemseged F (2010) Knowledge about obstetric danger signs among pregnant women in Aleta Wondo district, Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences 20: 25-32.

- Kabakyenga JK, Östergren P, Turyakira E, Pettersson KO (2011) Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness practices among women in rural Uganda. Reproductive Health 8: 33.

- Killewo J, Anwar I, Bashir I, Yunus M, Chakraborty J (2006) Perceived delay in healthcare-seeking for episodes of serious illness and its implications for safe motherhood interventions in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition 24: 403.

- Aborigo RA, Moyer CA, Gupta M, Adongo PB, Williams J, et al. (2014) Obstetric danger signs and factors affecting health seeking behaviour among the Kassena-Nankani of northern Ghana: a qualitative study: original research article. African Journal of Reproductive Health 18: 78-86.

- Mbalinda, SN, Annettee N, Kakaire O, Osinde MO, Kakande N, et al. (2014) Does knowledge of danger signs of pregnancy predict birth preparedness? A critique of the evidence from women admitted with pregnancy complications. Health Research Policy and Systems12: 60.

- Radoff KA, Levi AJ, Thompson LM (2013) A radio-education intervention to improve maternal knowledge of obstetric danger signs. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 34: 213-219.

- Yidana A, Kuganab-Lem R (2014) ‘Falling on the Battlefield in the Line of Duty’is not an Option: Knowledge as a Resource for the Prevention of Pregnancy Complication in Rural Ghana. Public Health Research 4: 120-128.

- World Health Organization (2012) Health education: theoretical concepts, effective strategies and core competencies: a foundation document to guide capacity development of health educators.

- Dako-Gyeke P, Aikins M, Aryeetey R, Mccough L, Adongo PA (2013) The influence of socio-cultural interpretations of pregnancy threats on health-seeking behavior among pregnant women in urban Accra, Ghana. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 13: 211.

- Roberto AJ, Goodall CE (2009) Using the extended parallet process model to explain physician’s decisions to test their patients for kidney disease. Journal of Health Communication 14: 400-412.

- Ensor T, Cooper S (2004) Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy and Planning 19: 69-79.

- Udofia EA, Obed SA, Calys-Tagoe BNL, Nimo KP (2013) Birth and emergency planning: a cross sectional survey of postnatal women at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health 17: 27-40.

- Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, Mavalankar D, Malay K, et al. (2006) Going to scale with professional skilled care. The Lancet 368: 1377-1386.

- Stock R (1983) Distance and the utilization of health facilities in rural Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine 17: 563-570.

- Yidana A, Mustapha I (2014) Contextualising Women Decision Making during Delivery: Socio-Cultural Determinant of Choice of Delivery Sites in Ghana. Journal of Public Health Research 4: 92-97.

- Ciccone, MM, Aquilino A, Cortese F, Scicchitano P, Sassara M, et al. (2010) Feasibility and effectiveness of a disease and care management model in the primary health care system for patients with heart failure and diabetes (Project Leonardo). Vascular health and risk management 6: 297-305.

- Lorig K (2003) Self-management education: more than a nice extra. Medical Care 41: 699-701.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15274

- [From(publication date):

August-2015 - Apr 03, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10624

- PDF downloads : 4650