Research Article Open Access

Qualitative Analysis of Third Year Medical Students Reflections on Loss

Deborah Morris*, Lauren Mazzurco, Mily Kannarkat and Marissa Galicia-CastilloDepartment of Medicine, The Glennan Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Virginia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Deborah Morris, MD, MHS

Assistant Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine

The Glennan Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology

Eastern Virginia Medical School, 825 Fairfax Ave

Suite 201, Norfolk, VA-23507-2007, Virginia, USA

Tel: 757-446-7040

E-mail: morris01@evms.edu

Received date: October 21, 2016; Accepted date: November 08, 2016; Published date: November 12, 2016

Citation: Morris D, Mazzurco L, Kannarkat M, Galicia-Castillo M (2016) Qualitative Analysis of Third Year Medical Student’s Reflections on Loss. J Palliat Care Med 6:288. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000288

Copyright: © 2016 Morris D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Medical students face professional experiences of death and loss during their formative training years. Personal experiences of death and loss are unique to each individual student. Surprisingly little is known about how medical students conceptualize loss or death. We sought to explore the responses of third year medical students to a selfreflection exercise focused on loss. We conducted a qualitative analysis of 127 third year medical school students responses to identify common and uncommon themes and language used by medical students to discuss and conceptualize loss. These findings may allow educators to tailor education programs on end of life care and mindfulness in a real and relevant manner. In addition, the wide breadth of student perspectives will inform appropriate support and resources required as physicians-in-training face loss during their training.

Keywords

End-of-life care; Palliative medicine; Pain; Cancer; Dementia

Introduction

Medical students face professional experiences of death and loss during their formative training years. Personal experiences of death and loss are unique to each individual student. Medical schools are beginning to incorporate end-of-life topics and mindfulness training into curricula. Students often rely on behaviors and attitudes modeled by attending physicians and house staff to develop skills and selfefficacy in caring for dying patients [1].

However, many practicing physicians are not comfortable discussing death and many new physicians feel ill prepared to care for dying patients [2,3]. Surprisingly little is known about how medical students conceptualize loss or death [4]. Understanding how medical students view loss will allow educators to tailor education programs on end of life care and mindfulness in a real and relevant manner.

In addition, the wide breadth of student perspectives will inform appropriate support and resources required as physicians-in-training face loss during their training [5]. This study explores the responses of third year medical students to a self-reflection exercise focused on loss. We identify common and uncommon themes and language used by these learners to discuss and conceptualize loss and coping.

Methods

As part of a mandatory Palliative Medicine course in 2014, all 127 third year medical school students at Eastern Virginia Medical School were required to respond to the following self-reflection statement after participation in panel discussions and lectures:

Write about your own experience and feelings in dealing with the loss of a patient or a loved one (either professional or personal experience). What type of support would have been helpful?

The responses were not intended for research purposes and research exemption from the IRB. Responses were de-identified and compiled into text files for analysis by the course coordinator prior to distribution to investigators. Text responses were entered into qualitative analysis software designed specifically for use in qualitative data analysis and mixed methods research. We conducted a qualitative thematic content analysis using open coding and theme matrix techniques [6-8].

Investigators reviewed textual data of 30 subjects for common and recurrent themes, and developed an initial codebook. When possible, codes utilized subjects’ own words and the text itself served as source of concepts and constructs rather than from preconceived hypotheses or lists [6,7].

Subsequently, two separate investigators reviewed 10% of the transcripts. Blinded evaluation revealed five discrepancies in code application. Investigators reconciled differences to achieve consensus, and two additional codes were developed. After refinement, codes were then applied to all transcripts and reviewed for emergence of additional themes through an iterative process.

Throughout the coding process, codes and themes were reviewed for agreement and disagreement, and discussed for consensus. Qualitative content analysis of textual data was primarily performed, however we included quantitative frequency of thematic responses across the full sample in attempts to describe the common and diverse nature of responses.

Results

Defining Loss - Most often death

127 text responses were analyzed. More students related personal losses (N=98) than professional losses (N=28), with more stories related to death of family members and friends, than death of patients.

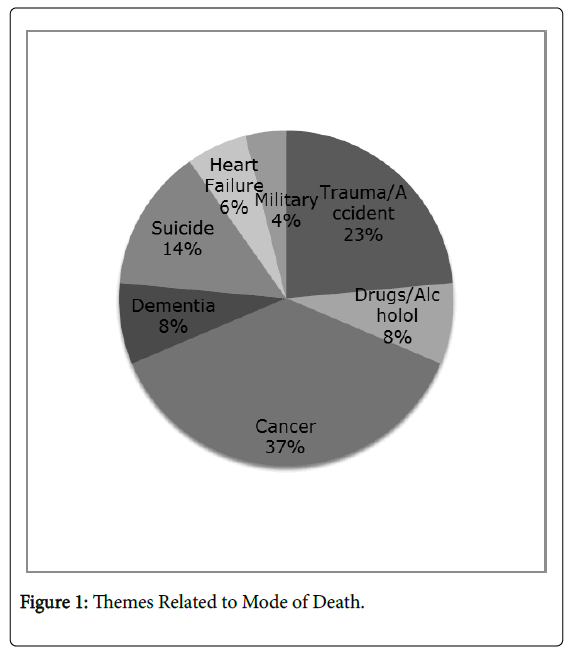

Students described specific mode of death in over a third of responses. Themes related to deaths from cancer (N=19), dementia (N=4), suicide (N=7), trauma (N=12), substance abuse (N=4), heart failure (N=3) and military (N=2) (Figure 1).

The descriptions of mode of death often included medical jargon even when describing personal accounts of loss.

“I watched my Grandfather pass away in the ICU. He received 37 minutes of Advanced Cardiac Life Support. When I arrived at his room he had already received 7 doses of Epi, and I knew. My family didn't really know, they were afraid, but they didn't know. I knew. I knew he wasn't coming back.”

Defining Loss: More than Death

Students frequently equated loss with death but some referenced loss of meaningful relationships. These respondents focused on loss and grief in relationships unrelated to mortality.

“The biggest loss that I have recently experienced was a breakup. . . I grieved for our relationship and the future we had planned. It took me 8 months to feel like a normal person again. . . .”

“I am lucky that I have not yet had to deal with a 'major' loss in my life. All of my immediate family members are living. One experience that seems appropriate to talk about, however, is losing touch with my brother due to his drug addiction. . . ”

While some respondents related personal experience with loss other than death, one individual verbalized experiencing no losses.

“I can't recall an experience in dealing with loss of the same caliber that our guest panel shared. The closest thing I can imagine is if I lost my husband someday. . . I can only imagine how devastating it would be if he were to be gone one day.”

Despite not describing a personal loss, the respondent was able to imagine potentially meaningful losses in her own life, and reflect on the deep emotion that might result.

Emotions

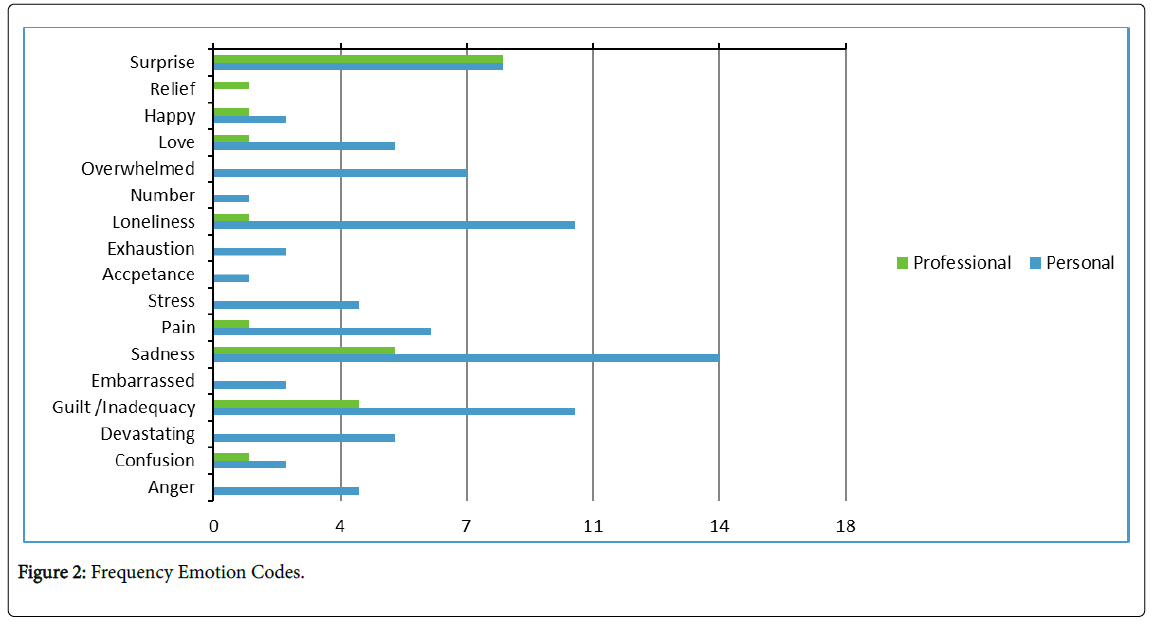

Nearly half of the text responses referenced emotions-47 in personal accounts and 15 in professional accounts of loss. Emotional themes were more often negative relating sadness, confusion, overwhelming stress, or pain (Figure 2).

Reflections also referenced positive emotions including joy and love in the face of loss. These accounts typically related lives well lived, shared experiences and legacy of loved ones.

“In the end it was a happy story, there was life to be celebrated. We did not attend the funeral of a hermit who met his unforeseen and untimely demise. Instead the church was filled with people who shared in the joy of his long and fulfilling life. He was a consummate family man, and one I will forever strive to be like. I did my best to cultivate a sentiment of joy and happiness at the thought of having known him despite normal human reaction to loss wanting us to do differently. I think about him daily and a smile always finds a way to manifest on my face. He made me a better human just by being him, and that is a legacy I can only wish to have on my future generations as he did his.”

Texts describing professional experiences of loss provided few accounts of positive emotions. Professional losses referenced families’ emotions separate from the student’s own feeling of surprise, guilt, inadequacy, and pain.

“When the first patient I knew well died, I changed. Seeing death for the first time in a person you've come to know over a few weeks is jarring. He was in hospice, but I didn't expect him to die while I was part of his care. I felt guilty, responsible”

“I was shocked... how had I not known? I had been in surgeries all morning, and hadn't heard any codes called, but I wasn't there for her death. In fact, I did not even know it had happened. I felt simultaneously left out, sad and guilty, thinking that I should have fought harder for the antibiotic course, or that I at least should have checked on Ms. P sooner... I should not have read about her death on a computer screen; that is not the type of provider I want to be.”

Students did find positive emotions among grieving family members, but were left with their own feelings of sadness:

“During my third year of medical school, I helped care for an older gentleman who passed away very unexpectedly. Because his family members had come to terms with his illness and had discussed what had happened when he would pass, they dealt with his loss very briefly and in a healthy manner. It was only a few minutes after his death that I heard laughter coming from the room, as his family began reminiscing the happy memories they cherished with my patient. But with this being my first real experience with death, I did not have such an easy time dealing with it. I felt sad, shocked, and I kept thinking about how hard he fought to continue living. I realized that there must have been many goals that he wished he accomplished, that he wasn't given the chance to do. It seemed as though his life was cut short, and that it was undeserved”.

Accounts of personal loss were laden with emotions. Respondents who discussed being in medical school or college during time of personal loss, often referenced feelings of stress, ambivalence and guilt brought on by distance and competing priorities.

“It was devastating when I learned of her passing away last year. I felt even worse because she had been in the hospital for two weeks, and because of school, I didn't go see her before she passed. It still makes me tear up when I think about how she is gone, but I always remember that she is watching over me.”

“I visited her every summer and we grew closer despite being geographically the farthest we had ever been from one another. Since starting medical school, however, my trips to Lebanon stopped and I went for three years without seeing my grandmother. Her passing was a shock to me. I never realized how ill she had become, and being overtaken with the stress and responsibilities of medical school prevented me from staying in touch with her as much as I would've liked to. The guilt from this is something I have yet to overcome.”

“At the time, I wish I'd had more academic support from my friends. I wish someone had offered to study with me or let me borrow their notes. I had to make sure I sought out what I needed entirely on my own when I went to his funeral (a reasonably far distance of 5 hours away). It was exhausting on top of the already exhausting task of bereavement. “

The theme of regret was evident in the use of “I wish” statements that students used to convey their desire for more knowledge or different actions for themselves, for their loved ones, or for the healthcare team.

“I wish I had known more about life and death.”

“I think it would have been nice if the idea of concept/comfort care had been broached with us. My mom had a very bleak prognosis so such an arrangement would likely have been best for my mom and our family. Instead, she endured very challenging treatments which the doctors admitted were likely not doing a lot for her, especially in light of the side effects. I wish we had had this option on the Table 1 when we were deciding how to proceed.”

“In retrospect I wish I'd had more information on his progress at the time. That way I could have been better prepared for him to go downhill quickly and ultimately to die. While my family was extremely supportive of each other after he was gone, I wish I had known more about what was going on along the way. In a way, it would have been nice to be included.”

Support and Coping

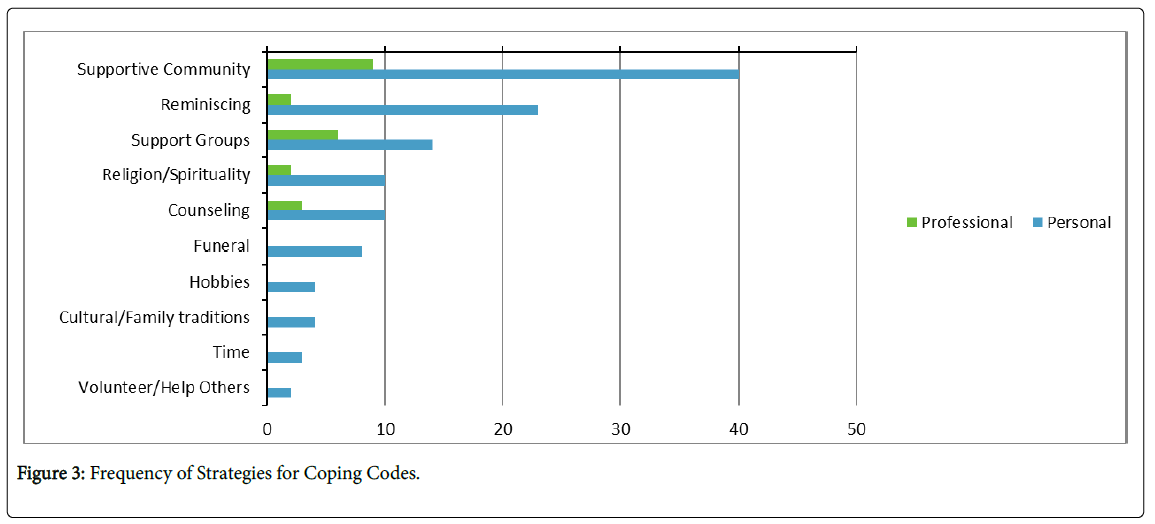

68% of respondents referenced specific strategies for coping with their loss (Figure 3). Themes of individuality were described as students reflected on the unique experience of grief and coping.

“With lecture today and reflecting on some of my own experiences, I realize that there is a huge “human element” to medicine and as physicians we are in a unique position to help patients through death, dying and grieving, keeping in mind that each person's journey will be unique and different.

“I have a large family, and it was therapeutic just being with all of them. Everyone deals with loss differently”

Most often, supportive family and community were cited as helpful.

“Even though none of this can take away the pain of losing a loved one, I felt that it definitely helped to talk about what we were going through with social workers, teachers/counselors and even each other.”

In addition to supportive communities, it was important to respondents to share their experience of loss with others who had been through similar experiences- to talk, share, and learn.

“Being able to talk with other students that have lost loved ones and been unable to be with them before or after medical school helped somewhat, but meeting up with more people and hearing their coping mechanisms may have helped more. They might have a unique strategy that helps them cope with the loss or focus on their work better. I could at least learn better ways to deal with a similar situation if it should happen again”.

“It was extremely comforting to me to have someone to confide in and commiserate with that DID know how I felt. I think talking to someone who had never lost a grandparent would not have been as comforting and would not have met my needs”.

Individuals valued support from those who had been through similar loss.

“You need to know to understand.”

“Dealing with the loss of a loved one is particular horrible when you don't feel like there's anyone you can turn to and that no one understands your pain. But I think what is most helpful is talking to someone who has had a similar loss, not because they'll “get it”; but because they won't say stupid things because they have at least an idea of what you went through.”

Superficial support vs. genuine empathy

Many respondents reflected on behaviors in friends, family members, and healthcare providers that were not helpful during their experience of loss. Many students contrasted superficial communication with demonstrations of genuine empathy

“Those responses felt very superficial--transient curtesies that honestly conveyed more of a sense of my classmate's discomfort with death than true sincerity.”

“For me, in my situation, I found that I didn't want people to tell me that it was going to be alright, or that they know how I feel, what I needed was just someone to be there with me. I found that the most comfort I got was just sitting with a couple of my friends. They didn't need to say anything and I didn't want them too, but just to have someone there, knowing that they supported me and were there for me was all I could ask for. Again, this relates to the unique nature of every person's grief. For me all I needed was the physical presence of two of my friends sitting next to me with one of them having a hand on my shoulder and nothing needed to be said.”

Supportive listening was often cited as a frequent useful strategy to demonstrate empathy.

“In general, it's helpful for people just to empathize and be supportive either by listening to your thoughts or helping you take your mind off of them. Sometimes just knowing someone is willing to listen is comforting on its own.”

In both personal and professional accounts, respondents describe lack of clear communication from healthcare providers as detrimental.

“It seemed that the doctors knew early on that her prognosis was very poor but failed to mention that to us, her family. None of us thought that she could die from cancer in the space of a few weeks. Communication, or lack thereof was paramount in the devastation that occurred after her death. “

Respondents had clear expectations of healthcare providers to be able to provide support to patients and family members experience loss:

“It is a doctor's responsibility to not approach death, dying and grieving as cookbook medicine, but rather act as caring, compassionate, empathetic humans that respond and tailor our support to each patient and their need.”

Discussion

Encounters with death and dying are inevitable for physicians during the course of their career. There is a lack of recognition, let alone formal process, for training our future physicians to cope with the death of patients who are under their care. Curricula are already strained for time and concepts not formally tested on licensing exams are given lower priority. Additionally, the “hidden” curricula, particularly in the clinical years of undergraduate medical education, can serve to unintentionally reinforce deprioritization of coping strategies that may be developed in the pre-clinical years. Unfortunately, the belief that “death is failure” is still prevalent and can significantly affect a medical student’s personal perspective of themselves and their role in patient care.

In this study, we found that many medical students have already experienced some type of loss, many personal, some professional. These learners have already developed a sense of empathy and a need for genuine communication. From the standpoint of professional loss, there are few resources to help medical students process, debrief and reinforce positive effects on personal impact [3]. Using students own words to share perceptions of loss, may have tremendous impact on their peers. Future research will examine the use of group debriefing to reframe medical student’s negative perceptions of loss.

Clearly medical students’ emotional response to loss varies by individual however, we need to provide a supportive structure in which learners can develop skills to articulate their feelings and common coping strategies [4]. Developmental models should focus also on positive aspects – such as reward of a relationship, appropriate laughter, and finding meaning. As students learn to identify and balance competing priorities, we must emphasize value in relationships, both personal and professional. Medical school policies and resources should reflect the importance of addressing loss in the development of professional behavior.

Today’s physicians face an environment filled with a myriad of new and different stresses such that many have taken the Institute for HealthCare Improvement (IHI) triple aim: better care, better health and lower costs and modified it with the addition of the importance of the physician wellness. Self-care and preservation are skills that need to be taught early in training to ensure physician well-being in a setting of high burnout [9]. Curricula should be structured to empower students to draw upon their own narratives to develop empathetic communication skills.

References

- Ratanawongsa N, Teherani A, Hauer KE (2005) Third-year medical students' experiences with dying patients during the internal medicine clerkship: a qualitative study of the informal curriculum. Acad Med 80: 641-647.

- Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, Baum SK, Virnig BA, et al. (2010) Physician factors associated with discussions about endâ?ofâ?life care. Cancer 116: 998-1006.

- Gibbins J, McCoubrie R, Forbes K (2011) Why are newly qualified doctors unprepared to care for patients at the end of life? Med Educ 45: 389-399.

- Williams CM, Wilson CC, Olsen CH (2005) Dying, death, and medical education: student voices. J Palliat Med 8: 372-381.

- Rebecca W, Quince T, Benson J, Wood D, Barclay S (2013) Medical students’ experience of personal loss: incidence and implications. BMC Med Educ 13: 36.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J (1994) Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

- Anselm S, Corbin J (1990) Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15: 1277-1288.

- Blackwelder R, Watson KH, Freedy JR (2016) Physician Wellness across the Professional Spectrum. Prim Care: Clinic Offic Prac 43: 355-361.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 10419

- [From(publication date):

November-2016 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9630

- PDF downloads : 789