Psychosocial Wellbeing of Black Youth in the Age of Hip-Hop: From Theory to Practice

Received: 01-Dec-2017 / Accepted Date: 13-Dec-2017 / Published Date: 15-Dec-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000573

Abstract

Introduction: Throngs of young people are disengaging from public “schooling”, opting instead for an alternate reality depicted in popular youth culture (PYC) and popular youth music multimedia (PYMM), in particular. This alternative reality is disturbingly real with images, messages, and stereotypes that may be perceived as promoting highly risky, problem behaviors, while often failing to present the consequences of these behaviors. Adolescents most at risk for negative outcomes in public schools are also most at-risk for negative health and social outcomes, both in and out of school. Clinicians and practitioners concerned with improving health outcomes by promoting healthy lifestyles must address the psychosocial wellbeing of these vulnerable youth. Leveraging the ubiquitous appeal of PYMM for health-enhancing, prosocial learning offers key stakeholders culturally-relevant and culturallyresponsive options that require critical thinking about prevailing themes and messages in popular music.

Objective: Two research questions were explored: 1) What are students’ perceptions about the potential influences that PYMM may have on their self-image and identity development, values, communication norms, and coping skills? and 2) What are students’ perceptions about the potential influences that faith, hope, love, and optimism may have in facilitating self-awareness, personal responsibility, social awareness, and social responsibility?

Method: Students completed an onsite post-intervention survey that consisted of thirteen questions graded on a nominal scale (i.e., yes/no) indicating the degree of agreement with the statements.

Results: Findings suggest black youth in Baltimore are aware of the potential influences that PYMM has on their attitudes, beliefs, values, and behaviors and welcome the opportunity to have critical discussions about the role of PYMM in their lives.

Discussion: This study and its results offer additional evidence supporting use of PYMM for culturally-relevant and culturally-responsive teaching and learning to promote health, and specifically address the psychosocial wellbeing for urban youth.

Keywords: Black youth; Psychosocial wellbeing; Youth engagement; Youth development; Health education; Social emotional learning; Music media literacy; Health literacy; Culturally-relevant; Culturallyresponsive; Popular youth music multimedia; Urban youth

Introduction

There are significant gaps in the literature about empirically validated strategies to improve student engagement, promote health and prosocial behaviors, and purposefully use select features of popular youth culture (PYC) as context and popular youth music multimedia (PYMM) as content and “text” for pedagogically-driven teaching and learning. Most studies that offer evidence of improved youth engagement do not specifically address the mechanisms by which improvements were achieved and what youth engagement looks like. Discovering and understanding the mechanism to engage young people and what drives their willingness to discuss and consider prohealth, prosocial behaviors could be a significant contribution to the literature for practitioners and researchers. Young people are clearly embedded in culture that has normalized and commodified risky and problem behaviors. The need to address this issue may be especially important for vulnerable black youth living at the intersection of race and poverty, with limited socialization beyond their own race or class.

Today, the school dropout rate is slowing down [1] as many school districts across the United States have found alternative ways of helping students earn a high school diploma [2]. The negative consequences of disengaging from school, or “dropping out”, remain a concern, particularly as competition for gainful employment remains stiff. While researchers have focused their inquiries on the predictors of dropout to develop effective dropout prevention programs [3], most education-based dropout prevention programs have focused on quantitative outcome measures, such as grades, state test scores, absenteeism, and disciplinary records. These factors were found to be significant predictors of dropout [4,5]; knowledge of these predictors has helped identify target groups for prevention efforts. This knowledge, however, has not shed much light on the bigger issueunderstanding motivation to complete school and the process preceding a student’s decision to “drop out” of school.

For this reason, many researchers now focus on the concept of school engagement to better understand what is believed to be a gradual process of disengagement, culminating in a student leaving school before completing the public “schooling” process [6,7]. Many researchers agree that, by the time a student completely disengages from traditional schooling, it is the end of a long process where the student has progressively become disengaged over time [5,8]. School engagement is necessarily the first topic on which to focus.

School engagement

Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris [9] found that engagement is comprised of three key components: behavior, affect (or emotion), and cognition. They describe the behavioral component as referring to a student’s participation in school activities (i.e., academic, social, and extracurricular activities); the affective component referring to a student’s feelings associated with school (i.e., a student’s positive attitudes and reactions toward school, teachers, learning, and peers); and the cognitive component referring to a student’s efforts toward tasks requiring thought and mental mastery (i.e., how students feel about themselves and their work, their skills, and the strategies they employ to master their work) [10].

Other researchers have expanded the definition of school engagement asserting that it includes social and academic components that impact school completion or failure to complete school [7]. Social aspects, known as “school membership”, include a student’s attachments to peers and adults in the environment. Academic aspects address a student’s need to believe the efforts the student is being asked to exert or expected to expend on learning-related tasks are worthy of their time and energy. Additionally, students need to see value in the tasks and behaviors expected and required in school. According to Wehlage and colleagues [7], high levels of engagement along the academic and social dimensions contribute positively to a student’s decision to complete school. Conversely, without these types of engagement, a student is more likely to become disengaged in the “schooling” process and, eventually, leave school before graduating.

School disengagement

In addition to the theoretical perspectives on engagement, empirical studies have investigated the relationship between engagement and school dropout [5,11]. Most of these studies focus on a student’s negative behaviors, interpreted as a lack of engagement [9]. In most cases, a student’s decision to “drop out” is attributed to deficiencies within the student; however, this is not always the case. Key stakeholders may attribute this lack of engagement to young people without considering all the facts, most notably the fact that some schools lack clarity about the goals and objectives for black children.

Researchers often measure the behavioral aspects of disengagement, because this component is the most conducive to quantitative measurement. More research is needed, however, that considers cultural engagement with students growing up in the age of digital media and hip-hop. Specifically, more research is needed to assess how prevailing themes and messages in hip-hop may influence behavior.

Importantly, there is more than one form of disengagement. Emotional disengagement, for example, has been shown to be related to a student’s decision to dropout [9], as studies have found that feelings of alienation at school [8] and negative feelings about school are significant predictors of a student’s emotional disengagement and decision to dropout [4,12]. Cognitive engagement is another way a student may disengage. Few empirical studies have been conducted on cognitive engagement’s relationship to school dropout [9]; however, academic competence and cognitive engagement are inter-related. When used as a guide for interventions to improve school engagement, these studies suggest the importance of cultivating a student’s sense of belonging at school and helping a student see the value of school. Social and emotional engagements are also forms of engagement, and the lack thereof may lead to disengagement. Therefore, it is important to cultivate both, particularly for young people who are already at higher risk for negative school outcomes.

Cultivating school engagement

While the preceding research provides a foundation to understand engagement and its relationship to preventing school disengagement or dropout, it fails to address the question: “How does one cultivate engagement?” According to Fredericks et al. [9], studies responding to this question have highlighted autonomy, relatedness, and competence as key factors in engaging youth. Autonomy includes students having a sense of choice in the activities they pursue [13]. In this context, choice is contrasted with being told what to do, without presenting young people with options or giving the perception of having options. Additionally, students need to see that what they are being asked to do to accomplish the learning-related objectives is worthy of their time and effort. Young people must see value in what they are being asked to do in school. It is important to review the known risk factors for school dropout and consider the reasons strongly held traditions in many American schools do little to engage some students.

Some students are at higher risk for withdrawing from school or “dropping out”, based on race and class. These same factors contribute to why some youth are at higher risk for negative health and social outcomes resulting in health disparities.

Triple jeopardy: Race, class, and disease

Data from the National Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBSS) [14] are reported based on race and can be grouped into six categories of health risk behaviors and related health outcomes: 1) alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs; 2) media use; 3) interpersonal conflict; 4) sexual health and responsibility; 5) violence, aggression, and trauma; and 6) suicide and other mental health issues. Unintentional injury and safety are two additional topics of interest to this research team, based on the study being initiated in Baltimore, following the tragic death of Freddie Gray, a young man from Baltimore who was fatally injured while in police custody [15].

Students from low socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to attend underfunded schools with high student-to-teacher ratios. Morale in poorly-funded schools with limited resources tends to be lower than morale in well-funded schools with fewer resource limitations [16]. Negative perceptions about achievement, achievement gaps, and low morale can negatively impact a student’s academic performance [17]. This is likely the case in many large urban school districts. Baltimore City Public Schools is among the largest urban school districts with high rates of low literacy.

Children from low-income families display more emotional and behavioral problems than children from middle-class families [18]. In addition, children from low-income families experience more chronic stress than children born to middle and high-income families [19]. Frequent and sustained exposures to interpersonal conflict, crime, and violence can lead to feelings of depression, fear, anxiety, and hostility [20-22].

Referenced studies illustrate the need for employing innovative prevention-oriented approaches, as well as revisiting the curriculum and instruction currently considered “schooling”. One approach to addressing the need for more culturally-relevant schooling is to extend learning opportunities beyond the traditional school day, via afterschool or summer enrichment programs.

Such programs, when structured and cognitively stimulating, act as a protective factor in improving low-income students' academic performance [23]. Additionally, offering students a socio-cultural and psychosocial lens, through which they may view the intersection of race and class, may prove to be a culturally relevant and culturally responsive approach to teaching and learning, both in formal and informal learning spaces.

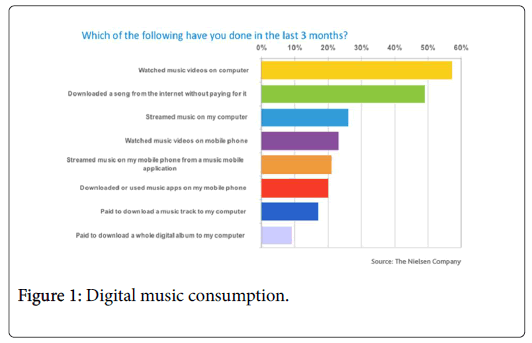

Popular Youth Music Multimedia (PYMM) will likely have broad appeal among adolescents, given documented media trends among younger consumers [24]. A study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2010 [24] tracked changes in children’s recreational media consumption from their childhood years, through their transitional period referred to as the ‘tween’ years, and into their late teenage years.

According to this study, youth in this age range spend more time engaged with media than any other activity, besides (maybe) sleeping. Music and digital media dominate the lives of youth growing up in the age of hip-hop, as shown in Figure 1 [25].

In a recent study assessing the prospect of using PYMM, Owens and Smith [26] found MusicsEnergy: The Message in the Music (ME-MIM) to be acceptable to 100% of rising 9th graders.

These students indicated that they would recommend this program to their best friends and that the use of popular youth music for critical thinking is an engaging approach to teaching and learning. Owens and Smith [26] also reported that students indicated ME-MIM was helpful in reflecting on their behaviors in and out of school, as well as their attitudes and beliefs about school.

Positive youth development and promoting competence in youth

Promoting competence

Based on a thorough review of the literature, positive youth development (PYD) often takes the form of programs and approaches that seek to address many of the developmental concerns occurring during adolescence. PYD model programs seek to promote competence, specifically, academic, behavioral, emotional, moral, and social competence [27]. In recent years, there has been greater emphasis on competence, especially in relation to skills required to thrive in the 21st century [28]. Importantly, there is research suggesting the enhancement of competence can help to prevent other negative academic and social outcomes [29]. Perhaps of even greater importance for research purposes, competence can be specified and measured independently, serving as its own outcome and indicator of positive development.

Many competence promotion efforts have worked toward developing skills that integrate feelings (emotional competence) with thinking (cognitive competence) and actions (behavioral competence). This integration is thought to help children achieve specific goals; these same three competencies serve as indicators of engaged learning.

Thus far, the literature on reasons some youth disengage from school and eventually leave before completing the schooling process has been reviewed. A definition of engagement has been provided, along with examples of what school engagement looks like. Some of the factors that foster engagement have been addressed. A definition of positive youth development (PYD) has been provided, as well as a list of the five core competencies linked to PYD. The case will now be made for reasons some students living at the intersection of racial stigma and poverty, who spend many hours in the gaze of recreational media, may be particularly vulnerable to negative influences therein. These same students may be more likely to disengage from an education that fails to address real and significant issues impacting them daily.

Why Baltimore?

Regional differences in adolescent risk behaviors reveal that 1 out of every 4 males attending high school in Baltimore City carried a weapon, such as a gun, knife, or club to school. In addition, nearly 1 out of every 8 female high school students carried a weapon to school [30].

Among large urban school districts, Baltimore City high school students lead the nation in the number of youth who carried a weapon on school property. Baltimore City Schools are in the top five school districts with students who had a weapon on school property, were in a physical fight, or were injured in a physical fight [30]. Among large urban school districts, Baltimore City high school students were among the top ten who were in a physical fight on school property and who have not attended school because of safety concerns. Additionally, these youth were among the top ten who attempted suicide and whose suicide attempt resulted in an injury, poisoning, or overdose that required medical treatment [30]. These youth were among the top ten who had ever used marijuana, tried marijuana for the first time before the age of 13 years, currently use marijuana, used cocaine or heroin, injected illegal drugs, and were offered, sold, or given an illegal drug by someone on school property [30]. Among large urban school districts, Baltimore City high school students were among the top five school districts in the nation who ever had sexual intercourse and who had sexual intercourse for the first time before age 13 years [30]. These statistics highlight health behaviors and health concerns tracked by the CDC. They also spotlight targeted behaviors reflected or correlated with prevailing themes and messages in PYMM, thereby presenting an opportunity to address if there is an interaction via primary data collection.

Based on the extensive research presented, black students attending Baltimore City schools may be at risk for the following four adverse outcomes: 1) school dropout; 2) school disengagement; 3) risky behaviors resulting in poor health outcomes; and 4) negative influences linked to media. Consequently, key stakeholders responsible for promoting school completion, health education, and prosocial behavior may find answers to the following questions helpful in their respective roles: 1) What are the potential influences that PYMM has on students’ self-image and identity development, values, communication norms, and coping skills? and 2) What potential influences does embracing faith, hope, love, and optimism have on facilitating self-awareness, personal responsibility, social awareness, and social responsibility?

The reviewed literature provides a theoretical framework to ask youth about the role PYMM plays in their identity, values, coping strategies and communication norms and the role personal attributes, such as faith, hope, love, and optimism, play in their self- and socialawareness. The following two research questions guided this study: 1) What are students’ perceptions about the potential influences that PYMM may have on their self-image/identity development, values, communication norms, and coping skills? and 2) What are students’ perceptions about the potential influences that faith, hope, love, and optimism may have in facilitating self-awareness, personal responsibility, social awareness, and social responsibility?

Methods

This was action research, as defined by Bradbury and Reason [31], building upon previous research following the Deployment-Focused Model (DF Model) of Intervention Development and Testing [32]. The DF-Model, as adapted by Molina, Smith, and Pelham [33], consists of six steps: 1) Assessment and Planning; 2) Staff Training; 3) Supervised Implementation; 4) Monitoring Implementation; 5) Two Way Feedback with Program Revisions; and 6) Ongoing Data Collection. This model, a multi-phase approach, starts with the assessment of the interventions’ feasibility and acceptability for practitioners in natural settings. The cycle consists of three steps [34]: 1) a pre-step which is to understand context and purpose; 2) six main steps to gather feedback, analyze data, plan, implement, and evaluate; and 3) a meta-step to monitor. Completing Step 1 in both research approaches (action research and DF-Model) was the focus of the present study.

Action research was appropriate, because it gave voice to Baltimore youth living at the intersection of race and class, with neither race nor class currently working in their favor. This is not because they are black and poor. Rather, this is because they are black, poor, and the targets of an industry that exploits them as consumers of risk behaviors commodified and promulgated as recreational entertainment, wreaking havoc among those most vulnerable. The voices of these black youth are often not included in the research process, other than for statistical reporting. Their perspectives, however, are of vital importance in this study about the psychosocial wellbeing of black youth in the age of hip-hop.

Two theories frame this research and help interpret the results: 1) the Social Cognitive Theory and 2) The Cultivation Theory. The Social Cognitive Theory [35] emphasizes that learning occurs in a social context; learning is primarily through observation. This theory has been applied extensively by researchers seeking to understand social behavior in schools. The Cultivation Theory [36] claims that persistent long-term exposure to media content has small but measurable effects on the perceptual beliefs, or “worlds”, of audience members [37].

The information generated by the limited number of participants was sufficient to adequately satisfy the purpose of this pilot study.

Research questions

The following two research questions guided this study: 1) What are the potential influences that PYMM has on students’ self-image and identity development, values, communication norms, and coping skills? and 2) What potential influences does embracing faith, hope, love, and optimism have on facilitating students’ self-awareness, personal responsibility, social awareness, and social responsibility?

Ethical protection of the participants

The procedures to ensure ethical protection of participants are outlined in the sponsoring University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) application. This study took place with IRB approval from the sponsoring University, as well as from the Baltimore City Public Schools (BCPS).

Participants

During the summer of 2017, data were collected from student’s participating in the Baltimore City Youth Leadership Institute (BCYLI)-a multi-site summer enrichment program, co-sponsored by a consortium of local philanthropists, the Center for Adolescent Health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, and BCPS. Participant recruitment was based on guidance in identifying a diverse population of students demonstrating a minimum level of academic strength and facing academic, attendance, and school engagement challenges resulting from obstacles within their homes and communities.

Ten high school students (n=10) from the BCYLI’s Academy of College and Career Exploration site participated in a customized pilot version of MusicsEnergy: Messages in Music (ME-MIM) over the course of five weeks. Eight (n=8) of these students completed a postintervention survey responding to 13 questions that were a subset of the two guiding research questions. Participants ranged in age from 15 to 19 years old, including a mix of rising 9th graders and graduating seniors. All participating students were black, most of whom did not read at grade level. The sample consisted of approximately an even number of males and females. The majority of these youth were from the East Baltimore neighborhood near the school, one of numerous low-resources, high-needs schools in Baltimore City. One hundred percent of the students in this study qualified for free or reduced lunch.

Setting

The physical setting for this study was in a classroom located within a Baltimore City public high school in East Baltimore. The study took place during the summer of 2017. ME-MIM was offered over the course of five weeks and consisted of seven sessions. All sessions were held before lunch.

Post-intervention survey

Students completed an onsite post-intervention survey that consisted of thirteen questions graded on a nominal scale (i.e., yes/no) indicating whether participants agreed with the statements. The survey was developed by a team consisting of two research scientists, one doctoral student and one undergraduate student. Results were analyzed via simple reporting.

Results

Study results are presented as Table 1.

| ME-MIM Responses from music energy BCYLI survey | (n=8) |

|---|---|

| Students who indicated ME-MIM did help them understand the link between their music preferences and: | Strongly Agreed |

| Communication norms in their environment. | 8 (100%) |

| Improving their sense of individual and group identity. | 7 (89%) |

| Improving their sense of values. | 7 (89%) |

| Improving their sense of coping skills. | 7 (89%) |

| Improving their sense of communication norms among peers. | 7 (89%) |

| Their attitudes about themselves. | 6 (75%) |

| Their attitudes about their community | 6 (75%) |

| Their attitudes about their peers. | 6 (75%) |

| Their attitudes about others. | 6 (75%) |

| Students who indicated ME-MIM did help them | |

| Improve their self-awareness about the potential role of F/H/L/O as personal attributes they may want to possess when dealing with moral dilemmas or stressful situations. F/H/L/O: Faith/Hope/Love/Optimism | 5 (63%) |

| Understand the link between their musical preferences and their attitudes about risky behavior. | 4 (50%) |

| Understand the influence music has on their attitudes about problem behaviors. | 3 (38%) |

| Students who indicated ME-MIM did not help them | |

| Think critically about healthy vs. risky vs. problem behaviors. | 5 (63%) |

| Understand the link between exposure to problem behavior and their perceptions of problem behavior or its consequences. | 5 (63%) |

Table 1: Participant survey responses.

Discussion

The following two research questions prompted this study: 1) What are the potential influences that popular youth music multimedia (PYMM) has on students’ self-image and identity development, values, communication norms, and coping skills? and 2) What potential influences does embracing faith, hope, love, and optimism have on facilitating students’ self-awareness, personal responsibility, social awareness, and social responsibility?

The perspectives of student participants are highly regarded in action research, because they hold important information. The researcher’s job is to seek a deeper understanding of the phenomenon and to serve more in the role of facilitator, working with stakeholders to peel back the layers comprising a phenomenon.

This is done in an attempt to discover and/or confirm core issues under investigation. In this study, the primary inquiry was about the potential influences of PYMM on students’ self-awareness in relationship to their identity development and formation, their values, their coping strategies, and their communication norms.

Based on the results, youth in this study were very aware of the potential influences that PYMM has on them, specifically, their selfimage and identity development, values, communication norms, and coping skills. When asked if ME-MIM, which uses PYMM, helped them understand if there is a link between their musical preferences and communication norms in their home, school, neighborhood, and community, all students surveyed indicated ME-MIM helped them understand there is a link. Most students surveyed also indicated that ME-MIM helped them understand the link between their musical preferences and improving their sense of self-awareness, specifically: 1) their own identity; 2) their values; 3) their attitudes about themselves; 4) their attitudes about their community-including their peers and others; 5) how they cope; 6) how they view traditional gender roles; and 7) how they typically communicate with others.

When asked if ME-MIM helped them understand of there was a link between their musical preferences and their attitudes about risky behaviors, at least half of those surveyed indicated that ME helped them understand there is link. Additionally, at least half of students surveyed indicated ME-MIM helped improved their self-awareness about the potential role of faith, hope, love, and optimism as personal attributes they may embrace when dealing with moral dilemmas or stressful situations. Interestingly, most of the students surveyed indicated that ME-MIM did not help them see any relationship between their exposures to problem behaviors, either in real life or via music multimedia, and their perceptions about problem behaviors and the consequences.

These results reflect a few important takeaways that may be useful for clinicians, practitioners, and school personnel currently looking for culturally-relevant, evidence-based strategies to encourage pro-health and prosocial behaviors among adolescents.

Lack of an evidence-based intervention that uses PYMM for pedagogically-driven teaching and learning, and that measurably improves school, health and youth development outcomes presents a unique and timely opportunity for ME-MIM, and similar research approaches. Outcomes linking engaged learning, and school connectedness with pro-health, pro-social, and competencies would provide considerable insight into the dilemma of growing numbers of youth disengaging from traditional “schooling”.

We need to know what motivates young people to consider prohealth, pro-social behaviors, given they are embedded in a culture that promotes the risky, anti-social behaviors. Understanding what motivates young people to consider pro-health, pro-social behaviors is critically important, given they are embedded in a culture that promotes the opposite. The knowledge gleaned from this study may be especially useful to scholars and practitioners who work with vulnerable black youth.

Context matters. Understanding what motivates a student to complete school and stay engaged in the schooling process may differ based on race and class, which are quite likely co-factors in a students’ decision to stay in school or “dropout”. Engagement students consists of being engaged affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively. While this much is well known, theories about school disengagement or engagement do not account for the lack of clarify about the goals and objectives that are unique to black students living in poverty. This clarification is needed based on the intersection of race and class and the known impact among poor, black youth.

A European, patriarchal standard, which presumes white superiority, is problematic for growing numbers of disengaged students who bring with them greater diversity and multicultural perspectives. Since we know that cultivating a sense of community or “belonging” in school is key to students staying engaged in the “schooling” process, it is important to cultivate social and emotional learning for all students. Cultivating social and emotional learning may be more important for those already at higher risk for disengaging from school or traditional “schooling”.

Concerned stakeholders should be careful not to mistake the behaviors of a “disengaged” youth as deficiencies within the student. Those sincerely looking for solutions must not ignore the facts regarding the convergence of digital media and the plethora of unsavory content available to both young and old consumers. In March 2017, weekly on-demand audio streaming soared past 7 billion, and the first six months of 2017 alone, on-demand audio and video streams was near 286 billion. That represents a 36% increase over the first six months of 2016 and a 74% increase compared to just three years ago [38]. Most of the streaming data reflects younger users, as streaming is most popular among these consumers.

YouTube is the first choice to access music among adolescents [39]. Younger listeners are the highly-prized targets. This study included discovering and discussing the musical preferences of young people in Baltimore. The content, context, and ‘text’ was used to prompt rich discussions about health, hope, and healing and music’s role in their young lives. Today’s young people are quite engaged in an alternative reality that has become their very own “reality”. That alternative reality is one filled with images and messages promoting highly risky, problem behaviors. Today, many young people and their parents struggle to discern what is “real” and what is truth. Those most “at-risk” for negative school outcomes in our public schools are also “at-risk” for negative health and social outcomes, such as early substance use, early entrance into the criminal justice system, early exposure to violence and trauma, early sexual activity, and unhealthy relationships. All of this is reinforced by the statistics reported previously in this manuscript.

Regrettably, these young people are not learning the skills necessary to fully participate in or benefit from a public education and often enter the labor market ill-prepared to thrive. They are increasingly disengaged in the status quo and increasingly engaged in social media and popular (youth) culture. Many of today’s youth are the children of millennial parents, meaning their parents were born between 1982-2004 [40]. This period was when media entertainment and online access converged via the World Wide Web. The Internet emerged and exists today with few restrictions on content, resulting in even more blurred lines regarding family values, healthy coping, communication norms, and a healthy sense of self. This is especially an issue for adolescence, a critical period of development during which young people are becoming more self-aware and forming their identity, clarifying their values, learning commination norms, and grasping for healthy coping strategies.

Clearly, there is a dilemma. However, the question is: Should “engagement” be viewed solely as the personal responsibility of each student or is the growing trend toward disengagement among young people more evidence of the need for a different type of “schooling”?

The future direction of this research is to partner with school and community-engaged stakeholders to create learning opportunities using ME-MIM and assessing its impact on school, health, and youth development outcomes. These discussions will also allow trained facilitators to probe further into the potential roles that faith, hope, love, and optimism may have on facilitating awareness and responseability linked to attitudes, beliefs, values, norms, and choices.

Prior to this study, ME-MIM was heavily focused on health and media literacy, without lessons or activities to facilitate self- and social awareness. Prompting young people to analyze their musical preferences and declare their intentions to avoid known risks proved to be more contextualized than anticipated and highlighted the need for four additional units of instruction. These are: 1) self-awareness; 2) social awareness; 3) relationship skills; and 4) self-management; in addition to 5) media literacy/advertising; and 6) responsible decisionmaking.

In addition to adding fidelity measures and integrating evidencebased practices and strategies, the future direction of this research includes moving on to Step 2 of the Deployment Focused Model (DF Model) of Intervention Development and Testing [32], initially developed by Weisz and adapted by Molina and colleagues [33]. This multi-phase/stage model begins with the development of an intervention that is assessed to determine its feasibility and acceptability to practitioners in their natural settings. The DF Model ends with an efficacy trial based on manualized procedures. The best outcome of the intervention development and refinement process is to have an effective and acceptable intervention in a manualized format that practitioners or Para-professionals can implement with minimum training and support. ME-MIM has been assessed to be both acceptable and feasible to key stakeholders, under certain conditions [26,41-43]. The next step in this process is to train facilitators and assess the effectiveness of these trained facilitators via fidelity monitoring and observing their interactions with participants.

Conclusion

In conclusion, concerned stakeholders must acknowledge that strongly held traditions in many American schools serving poor children do little to help young people understand the benefits of crossing cultural boundaries. The research is inconclusive on the topic of Ebonics; however, there are clear advantages and benefits to cultural code-switching [44], which would be in line with facilitating a student’s sense of attachment to others at school, and could potentially, bolster a sense of cultural competence for young people not inspired to speak the King’s English. Code-switching is the practice of alternating between two or more languages or dialects in conversation. It allows students to maintain kindred connections and familiar networks while also acquiring and practicing communication and social skills necessary to reap the full rewards and benefits in and out of school.

Deconstructing the origins of black inferiority is necessary to address social determinants of health such as race, class, and education. Such a dialogue may go a long way toward validating the psycho-social wellbeing, the emotional pain and struggle for hope that some black people, especially traditionally marginalized youth, may experience. We must explore new pathways to health, hope, and healing.

Grant Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Prevention Research Centers (PRC) Program at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Adolescent Health. The PRC Program is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) (CA# 1U48DP005045-01).

References

- Stetser MC, Stillwell R (2014) Public high school four-year on-time graduation rates and event dropout rates: School years 2010-11 and 2011-12. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Battin-Pearson S, Newcomb MD, Abbott RD, Hill KG, Catalano RF, et al. (2000) Predictors of early high school dropout: A test of five theories. J edu psychol 92: 568-582.

- Ekstrom R, Goertz M, Pollack J, Rock D (1986) Who drops out of high school and why? Findings from a national study. The Teachers College Record 87: 356-373.

- Rumberger RW (1987) High school dropouts: A review of issues and evidence. Review of edu research 57: 101-121.

- Archambault I, Janosz M, Fallu JS, Pagani LS (2009) Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. J adolesc 32: 651-670.

- Wehlage G, Rutter R, Smith G, Lesko NR, Fernandez (1989) Reducing the risk: School as communities of support. NASSP Bulletin 73: 50-57.

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH (2004) School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev Edu Res 74: 59-109.

- Metallidou P, Vlachou A (2007) Motivational beliefs, cognitive engagement, and achievement in language and mathematics in elementary school children. Int J Psychology 42: 2-15.

- Connell JP, Spencer MB, Aber JL (1994) Educational risk and resilience in African American youth: Context, self, action, and outcomes in school. Child develop 65: 493-506.

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD (1994) Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our time. Cambridge University Press.

- Ryan RM, Connell JP (1989) Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. J Pers Soc Psychol 57: 749-761.

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, et al. (2014) Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2013. MMWR 63: 1-163.

- Wear D, Zarconi J, Aultman JM, Chyatte MR, Kumagai AK (2017) Remembering Freddie gray: Medical education for social justice. Acad Med 92: 312-317.

- Kozol J (1991) Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools. Crown Publishers, New York.

- Adams CD, Hillman N, Gaydos GR (1994) Behavioral difficulties in toddlers: Impact of socio-cultural and biological risk factors. J Clin Child Psychol 23: 373-381.

- McLoyd VC (1990) The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev 61: 311-346.

- Attar BK, Guerra NG, Tolan PH (1994) Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events and adjustments in urban elementary-school children. J Clin Child Psychol 23: 391-400.

- Kotlowitz A (1991) There are no children here: The story of two boys growing up in the other America.

- Richters JE, Martinez PE (1993) Violent communities, family choices, and children's chances: An algorithm for improving the odds. Dev Psychopath 5: 609-627.

- Posner JK, Vandell DL 0(1994) Low-income children's after-school care: Are there beneficial effects of after-school programs. Child Dev 65: 440-456.

- Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF (2010) Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8 to 18-year-olds: A Kaiser family foundation.

- Owens JD, Smith BH (2016) Health education and media literacy: A culturally-responsive approach to positive youth development; J Health Edu Res Dev.

- Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JA (2004) Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann Ame Acad of Polit Soc Sci 59: 198-124.

- Botvin GJ, Schinke SP, Epstein JA, Diaz T, Botvin EM (1995) Effectiveness of culturally focused and generic skills training approaches to alcohol and drug abuse prevention among minority adolescents: Two-year follow-up results. Psychol Addict Behaviors 9: 183.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2013. Surveillance summaries 36: 1-4

- Bradbury H, Reason P (2003) Action research: An opportunity for revitalizing research purpose and practices. Qualitative social work 2: 155-175.

- Weisz JR (2004) Psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Evidence-based treatments and case examples. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Molina BS, Smith BH, Pelham WE (2005) Development of a school wide behavior program in a public middle school: An illustration of deployment focused intervention development, stage 1. J Atten Disord 9: 333-342.

- Coughlan P, Coghlan D (2002) Action research for operations management. Int J Operat Prod Manag 22: 220-240.

- Bandura A, National Inst of Mental Health (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice- Hall, Inc.

- Gerbner G, Gross L (1973) Cultural indicators: The social reality of television drama. ERIC.

- Ferguson LE (2016) Examining generational and gender differences in parent-young adult child relationships during co-residence. Portland state University Library.

- Owens JD (2015) Can popular youth music and media be a culturally-informative approach to address health education, media literacy and diversity in schools? J Edu Soc Policy 2: 120-129.

- Owens JD (2015) Adolescence in the digital entertainment age: A learner-centered, culturally-engaging approach to health and media literacy. University of South Carolina, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing 3704381

- Owens JD, Weigel DA (2017) Addressing minority student achievement through service learning in a culturally-relevant context. J Service LearnHigher Edu.

- Thompson FT (2000) Deconstructing ebonic myths: The first step in establishing effective intervention strategies. Interchange 31: 419-445.

Citation: Owens JD, Harper PTH, Reynolds SD (2017) Psychosocial Wellbeing of Black Youth in the Age of Hip-Hop: From Theory to Practice. J Community Med Health Educ 7: 573. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000573

Copyright: ©2017 Owens JD, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 8474

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Apr 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 7649

- PDF downloads: 825