Research Article Open Access

Promoting Factors and Barriers to Participation in Early Phase Clinical Trials: Patients Perspectives

Patricia Chalela1, Lucina Suarez1, Edgar Muñoz1, Kipling J Gallion1, Brad H Pollock2, Steven D Weitman3, Anand Karnad3 and Amelie G Ramirez1*1Institute for Health Promotion Research, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, USA

2Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, USA

3Cancer Therapy & Research Center, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Amelie G Ramirez

Institute for Health Promotion Research

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

7411 John Smith Dr., Suite 1000, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

Tel: 210-562-6500

Fax: 210-562-6545

E-mail: ramirezag@uthscsa.edu

Received Date: October 19, 2013; Accepted Date: April 21, 2014; Published Date: April 24, 2014

Citation: Chalela P, Suarez L, Munoz E, Gallion KJ, Ramirez AG, et al. (2014) Promoting Factors and Barriers to Participation in Early Phase Clinical Trials: Patients Perspectives. J Community Med Health Educ 4:281. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000281

Copyright: © 2014 Chalela P, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: Inclusion of minorities in clinical research is an essential step to develop novel cancer treatments, improve health care overall, understand potential differences in pharmacogenomics and address minorities’ disproportionate cancer burden. However, Latinos and other minority groups continue to be critically underrepresented, particularly in EPCTs. The objective of the present study was to explore barriers and promoting factors influencing patients’ decisions to enroll or not in early phase clinical trials (EPCTs) and identify areas for intervention to increase minority enrollment into clinical research.

Methods: An interviewer-administered survey was conducted with 100 cancer patients in the predominantly Latino region of South Texas. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify underlying dimensions, and multiple logistic regressions assessed significant factors that promote or deter patients’ enrollment to EPCTs. In addition, a separate subgroup mean analysis assessed differences by enrollment status and race/ethnicity.

Results: For one standard deviation increase in the importance given to the possibility of symptoms improvement, the predicted odds of refusing enrollment were 3.20 times greater (OR=3.20, 95% CI=1.06-9.71, p 0.040). Regarding barriers, among patients who considered fear/uncertainty of the new treatment a deterrent to enrollment, one standard deviation increase in agreement with these barriers was associated with a 3.60 increase (OR=3.60, 95% CI=1.30-9.97, p 0.014) in the odds of not being enrolled in an EPCT. In contrast, non-enrolled patients were less likely (OR=0.14, 95% CI=0.05-0.44, p 0.001) to consider fatalistic beliefs as an important barrier.

Conclusion: This study, one of the first to identify South Texas patients’ barriers to enroll in EPCTs, highlights potential focal areas to increase participation of both minority and non-minority patients in clinical research. Culturally tailored interventions promoting patient-centered care and bilingual, culturally competent study teams could solve language barriers and enhance Latinos’ likelihood of joining clinical trials. These interventions may simultaneously increase opportunities to involve patients and physicians in clinical trials, while ensuring the benefits of participation are equitably distributed to all patients.

Keywords

Clinical trials; Barriers; Promoters; Cancer patients; Early phase; Enrollment

Introduction

Adequate inclusion of minorities in clinical research is an essential step to develop novel cancer treatments, improve health care overall, understand potential differences in pharmacogenomics [1,2], and address minorities’ disproportionate cancer burden [3-5]. Without adequate minority representation in early-phase clinical trials (EPCTs; referring to trials in Phase I or II), researchers cannot assess differential effects among groups or ensure the generalizability of trial results [3,5,6]. However, inclusion of underrepresented groups in clinical trials has proven a significant challenge. Almost two decades after the National Institutes of Health (NIH) mandate to ensure inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research, Latinos and other minority groups continue to be critically underrepresented [3,5]. Of all patients enrolled in publicly funded National Cancer Institute (NCI) clinical trials, only 8% were African American and 5% were Latinos [5,7]. These populations experience disparities in cancer incidence, mortality, survival, and other cancer care issues [4,8-10].

Barriers to the participation of minorities in clinical trials include study design (e.g., protocol length and complexity, patient exclusion criteria), healthcare system barriers (e.g., lack of cultural competence among staff, lack of minority staff), and physician- (e.g., lack of referrals and misconceptions about patients’ compliance) and patient-related factors [11-17].

Patients’ most frequently cited barriers to EPCTs participation include lack of awareness of available clinical trials, lack of knowledge about disease and treatment options, and lack of understanding about the trial process, including randomization, and treatment preference [11,12,14,17-20]. Potential trial participants raise additional fears related to unknown reactions and side effects, the possibility of sacrificing quality of life, fear of being a guinea pig, and feelings of lost control [3,11-14,17,19,21]. The most frequently cited barriers to clinical trial participation were mistrust of research and the medical system [3,12]. Practical barriers, such as lack of transportation, lack of health insurance, financial constraints, lack of family support, trial duration, and high frequency of office visits also have been found to deter patients from participating in clinical research [3,11,12,14,17]. In addition, language, acculturation, health literacy, attitudes, beliefs, and lack of knowledge regarding clinical research pose additional barriers to participation [12,17-19]. Other barriers include lack of physician referrals, comorbidities that may limit provider referrals, recruitment criteria or investigator recruitment bias (e.g., investigator feels the case is too complex), trials not always available at the patient have designated treatment sites, and provider-patient communication issues [11,12,14-20].

Frequently cited factors that promote participation in clinical trials include expectations for health improvement, the opportunity to access the latest and best treatment, the potential to control the disease or improve chances for a cure, the benefit to other future patients, and feelings of hope. Additional factors include family and social influences, recommendations from one’s own doctor, and provision of transportation and incentives [3,11,12,18,21-28].

While researchers have focused on later-phase clinical trials, very little is known about the factors that impact enrollment of patientsparticularly Latinos and other minorities-into EPCTs. Although laterphase trial research provides insight on improving accrual into EPCT, differences in EPCTs-eligibility criteria, expected clinical outcomes, and limited geographic availability-inferences from later stage trials may not be generalizable. In contrast to later-phase trials, EPCT patients usually have no known effective treatment options, have had multiplerelapses or were refractory, and have exhausted nearly all conventional options without success, and thus face unique concerns, including end-of-life issues [19]. Unfortunately, there is limited knowledge about how to design effective interventions that would increase minority enrollment in EPCTs.

This study aimed to explore barriers and promoting factors influencing patients’ decisions to enroll or not in early-phase clinical trials (EPCTs) and identify areas for intervention to increase minority enrollment into clinical research at the Cancer Therapy and Research Center (CTRC). The CTRC, a National Cancer Institute (NCI)- designated cancer center at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, is the only cancer center in South Texas, a 38-county region that is predominantly Hispanic (69%).

Materials and Methods

Participants and data collection

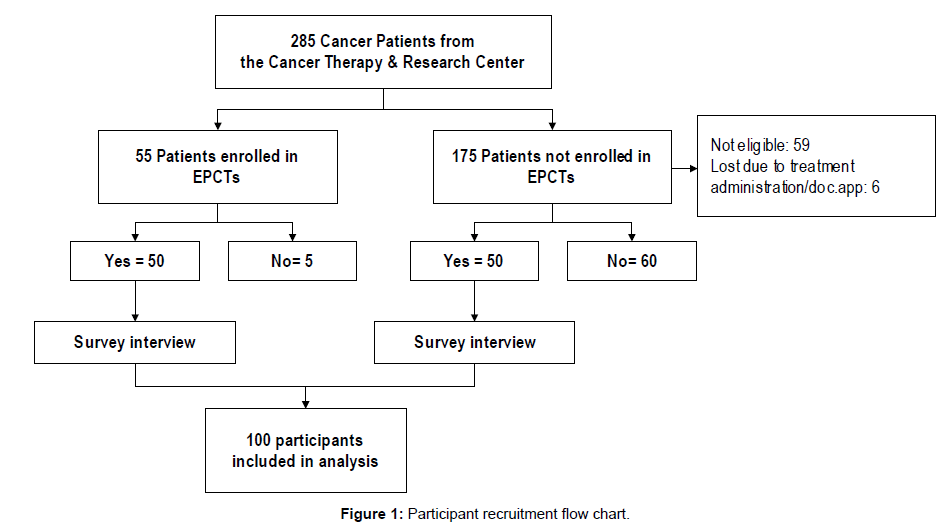

Participants were patients receiving treatment at the Cancer Therapy and Research Center (CTRC). An interviewer-administered survey was conducted with 100 cancer patients identified through medical records to explore barriers and promoting factors associated with EPCT enrollment decisions. Among the 100 patients, 50 were enrolled in EPCTs and 50 were not enrolled in an EPCT and would decline if invited. These latter patients were asked about their hypothetical participation in an EPCT if given that option. Patients who responded that they would not enroll in a clinical trial were invited to take the survey. This method of selecting a comparison group to EPCT enrollees was chosen because of the difficulties recruiting participants who had already rejected the invitation to be in an EPCT, given that there was no information of their refusal in their medical records. All participants were informed of the survey’s anonymity, purpose (identify promoters/ barriers patients face in EPCT participation decisions) and use of study results (guiding an intervention to reduce barriers and increase EPCT participation among minorities, particularly Latinos). Patients were approached at the clinic by a member of the research team and invited to participate in the study. Those who agreed to participate were interviewed while they were receiving or waiting for their clinical trial treatment. The study was approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Board and all participants received a thank-you note and a $25 gift certificate for their effort (Figure 1).

Survey instrument

The questionnaire was developed based on information obtained from patient telephone interviews, a careful review of the literature, the research team’s own experience [15,16], questionnaires received from external researchers [18,22,25-31], and discussion with CTRC oncologists. The instrument then was reviewed by the research team and pre-tested with 10 CTRC cancer patients. The research team analyzed pre-test results, made necessary modifications, and finalized the survey. The survey took approximately 20 minutes to administer and was conceptualized on four general modules: information preferences, promoting factors, barriers to participation, and background/ demographic information.

Measures

Relevant demographic and background variables included information about the participant’s country of origin, age, gender, ethnic identification, marital status, health insurance status, educational level, occupation, income, and previous participation in a clinical trial. The survey also included two items about how the participant first heard about EPCTs (for clinical trial participants only) and the most effective ways to inform cancer patients about EPCTs (for all participants).

Promoters that encourage patients to participate in EPCTs included items about direct therapeutic benefit of new treatment (i.e., “Possibility that experimental treatment would control cancer”), high-quality medical care and follow-up (e.g., “Possibility of obtaining high-quality medical care), patient desire to try something new, encouragement by family and friends to join, not having a better option available, desire to be part of a research study and help future cancer patients, hope, and clarity or information received made easy to decide to participate. Barriers included items about the decisionmaking process (e.g., “Lack of understanding of trial process/purpose due to communication problems”), socioeconomic factors (e.g., “Cost/ lack of health insurance), distance and time expected to travel to the trial center, trial-related factors (e.g., “Having blood samples taken”), and beliefs and attitudinal factors (e.g., “Belief that disease is a death sentence”).

Data analysis

Twenty four cases had missing income data, an important variable widely known to be associated with enrollment. Cases with missing income data were compared with those with complete data and no significant differences were found in any key study variables. After conducting a Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test, imputation of missing values was performed using the Expectation Maximization algorithm provided by SPSS 20 [32-34], to improve efficiency of the regression analyses.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sociodemographic items and prior participation in clinical trials. Contingency table analysis was used for categorical variables (exact Chi-square test for nominal variables and Chi-square test for trend for ordinal variables) and comparison of means with t-tests for continuous variables was also used to assess differences between enrolled and non-enrolled participants.

Given the relatively small sample size and the number of promoter and barrier items, an exploratory factor analysis with the alpha factoring extraction method, based on maximizing the reliability of factors, was conducted to identify correlated items that could represent one or more underlying dimensions of promoters and barriers [35]. Anderson-Rubin and simple sum methods were used to obtain factor scores for each dimension, and were evaluated using means testing [36].

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the association between predictor variables (including sociodemographic factors, promoter- and barrier-related dimensions) and enrollment on EPCTs. Variables were recoded as needed for logistic regression, and standardized scores for predictor variables were used to place the predictors on a common scale so that each had the same mean and standard deviation [37,38]. Magnitude of associations were represented with the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A step-wise process was used to remove non-significant items, and the most parsimonious model explaining the data was selected based on the log-likelihood statistic.

Finally, a separate subgroup mean analysis was conducted to assess differences by enrollment status and race/ethnicity. All statistical tests were two-sided and a p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS statistics version 20 [33].

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of participants. The mean age of participants was 55.2 years (SD=12.7). Most were born in the US (87%), with a similar distribution by gender (49% males). Forty seven percent were non-Hispanic whites, 39% were Hispanics and only 3% were of other race/ethnicity. Two-thirds were married/living with a significant other (65%), more than half had a high school or less education (57%) and almost two thirds had a family income of $25,000 or lower (64%). Only 16% had previously participated in a clinical trial. There was not a significant difference between the groups-those enrolled in clinical trials and those who were not enrolled and would decline the invitation to do so-by age, gender and insurance. However, significantly more respondents in the group that would not participate were Latinos (p<0.001), married/living with partner (p<0.028), had lower educational levels (p<0.001), had lower family income (p<0.001) and had not participated in a clinical trial before (p<0.001).

| EPCT Enrollment | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled(n= 50) | Non-Enrolleda(n= 50) | (N=100) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | N | % | pb | ||

| Patient's age: mean, (SD) | 56.14 (11.5) | 54.24 (13.9) | 55.19 (12.7) | 0.457 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 28 | 56.0 | 21 | 42.0 | 49 | 49.0 | 0.161 | |

| Place of birth | ||||||||

| United States | 47 | 94.0 | 40 | 80.0 | 87 | 87.0 | 0.026 | |

| Mexico | 1 | 2.0 | 9 | 18.0 | 10 | 10.0 | ||

| Other | 2 | 4.0 | 1 | 2.0 | 3 | 3.0 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 39 | 78.0 | 8 | 16.0 | 47 | 47.0 | <0.001 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 8 | 16.0 | 31 | 62.0 | 39 | 39.0 | ||

| Other | 3 | 6.0 | 11 | 22.0 | 14 | 14.0 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/Living with a significant other | 39 | 78.0 | 26 | 52.0 | 65 | 65.0 | 0.028 | |

| Separated/Divorced | 5 | 10.0 | 7 | 14.0 | 12 | 12.0 | ||

| Widowed | 2 | 4.0 | 10 | 20.0 | 12 | 12.0 | ||

| Single/Never married | 4 | 8.0 | 7 | 14.0 | 11 | 11.0 | ||

| Educational level | ||||||||

| High School or less | 19 | 38.0 | 38 | 76.0 | 57 | 57.0 | 0.001 | |

| Technical/Some College | 12 | 24.0 | 6 | 12.0 | 18 | 18.0 | ||

| College Degree or higher | 19 | 38.0 | 6 | 12.0 | 25 | 25.0 | ||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Employed | 19 | 38.0 | 10 | 20 | 29 | 29.0 | 0.002 | |

| Retired | 17 | 34.0 | 7 | 14 | 24 | 24.0 | ||

| Disabled | 10 | 20.0 | 19 | 38.0 | 29 | 29.0 | ||

| Unemployed | 4 | 8.0 | 14 | 28.0 | 18 | 18.0 | ||

| Have healthcare plan | ||||||||

| Yes | 46 | 92.0 | 41 | 82.0 | 87 | 87.0 | 0.137 | |

| Yearly Household Income | ||||||||

| $25,000 or less | 21 | 42.0 | 43 | 86.0 | 64 | 64.0 | <0.001 | |

| $26,000 - $50,000 | 9 | 18.0 | 6 | 12.0 | 15 | 15.0 | ||

| $51,000 and above | 20 | 40.0 | 1 | 2.0 | 21 | 21.0 | ||

| Have participated in clinical trials before | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 | 30.0 | 1 | 2.0 | 16 | 16.2 | <0.001 | |

bTwo-sided p-value from Chi-square tests for comparison of proportions and independent t-test for comparison of means.

Table 1: Characteristics of Study Participants by Enrollment Status.

Table 2 shows the dimensions identified through exploratory factor analysis for promoter and barrier items included in the survey.

| Dimension | Original surveyitems |

|---|---|

| Promoters-treatmentsoutcomeexpectationa | |

| Symptomsimprovement | • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwouldnot cause adverse/severesideeffects • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwoulddecreasehospitalization • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwouldimprovecurrentsideeffects • Possibilitythat experimental treatment is betterthanstandardtreatment • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwouldincreaseyourabilityto be active |

| Disease control | • Possibility of diseaseimprovement • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwould control cancer • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwouldextendlength of life • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwould cure cancer |

| High Quality Medical Care | • Possibility of obtainingcareful medical care and follow-up • Possibility of obtaininghigh-quality medical care • Possibilitythat experimental treatmentwouldimprovequality of life |

| Hopefulness | • Nothaving a bettertreatmentoption available • Desireto try something new • Desireto be part of a researchstudy • Joining the studygives hope |

| Medical teaminfluence | • Advicereceivedfromown doctor tojoin • Trial informationreceivedwasveryclear • Desiretohelpfuturecancerpatients |

| Social influences | • Encouragementfromfriendstojoin • Encouragementfromfamilytojoin • Trust in the Center conducting the trial |

| Barriersb | |

| DecisionMakingProcess | • Lack of understanding of trial processes/purposesduetocommunicationproblems • Lack of knowledgeabout the disease and treatmentoptions • Lack of knowledge/informationabout available trials • Doctors do notdiscuss trial optionwithpatients • Beingtoointimidatedtoaskquestions • Relianceon doctor as the mosttrustedsource of informationtomake the decision |

| Trial related | • Havingbloodsamplestaken • Number of times expectedfortreatment or evaluation • Duration of trial |

| Socio-economic | • Travelcost • Cost/Lack of healthinsurance • Time expectedtotravelto the center • Distancefrom trial center • Lack of family/social support |

| Distrust of the medical system | • Distrust of researchersdueto prior personal/familyexperience • Distrust of the medical system • Languagebarriers |

| Fear/uncertainty | • Fear of being a guinea pig • Fear of sacrificingquality of life • Fearthatresearchersconsider the scientificexperiment more importantthan the patients’ health • Fear of unknownreactions/sideeffects |

| Fatalistic/spiritual beliefs | • Feelings of hopelessness • Beliefsthatdisease is God’swill and nothing can be done • Beliefthatdisease is a deathsentence • Religious and spiritual beliefs |

Table 2: Dimensions Identified through Exploratory Factor Analysis and Original Survey Items.

Promoter and barrier differences between enrolled and nonenrolled EPCT participants using dimension summary scores are shown in Table 3. Mean differences between the two groups were significant for one dimension (symptoms improvement) within treatment expectations. There were no significant differences between the two groups for dimensions related to social and personal factors. Non-enrolled patients placed greater importance on symptoms improvement than those who were enrolled in EPCTs. In addition, non-enrolled patients were more likely to rank factors related to the possibility of disease control, high quality medical care and followup, and the influence of the medical team higher than their enrolled counterparts.

| Factors/(min-maxvalues) | EPCT Enrollment | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled (n=50) | Non-Enrolled (n=50) | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| TreatmentExpectationsPromoters | |||||

| Symptomsimprovement (5-25) | 18.84 | 5.32 | 22.98 | 2.58 | <0.001 |

| Disease control (12-20) | 18.92 | 1.95 | 18.82 | 1.78 | 0.789 |

| High quality medical care (5-15) | 13.80 | 2.05 | 14.20 | 1.26 | 0.243 |

| Personal/Social Promoters | |||||

| Hopefulness (6-20) | 15.22 | 3.84 | 15.50 | 4.17 | 0.727 |

| Medical teaminfluence (7-15) | 13.50 | 2.43 | 13.60 | 1.80 | 0.815 |

| Social influences (6-15) | 12.54 | 2.53 | 12.94 | 2.39 | 0.418 |

| Barriers | |||||

| Decisionmaking (6-24) | 19.52 | 4.16 | 19.82 | 3.20 | 0.687 |

| Trial related (3-12) | 7.62 | 2.52 | 8.20 | 2.35 | 0.237 |

| Socioeconomic (8-20) | 17.18 | 3.15 | 16.92 | 2.49 | 0.648 |

| Distrust of the medical system (3-12) | 7.10 | 2.88 | 8.90 | 2.84 | 0.002 |

| Fear/uncertainty of new treatment (4-16) | 11.32 | 3.68 | 12.66 | 3.12 | 0.053 |

| Fatalistic/Spiritual beliefs (4-16) | 11.36 | 3.06 | 8.66 | 3.21 | <0.001 |

Table 3: Means Comparison of Summary Scores of Promoters and Barriers by Enrollment Status (N=100).

Regarding barriers to enrollment, both groups tended to agree or strongly agree with decision-making processes, trial-related factors and socioeconomic barriers as important deterrents to participation in clinical trials.

There were significant differences between the two groups for three barrier-related dimensions. Non-enrolled patients tended to give higher score to distrust of the medical system and fear/uncertainty of new treatment, considering them important barriers that would keep them from enrolling in an EPCT, compared to enrolled patients. Interestingly, enrolled patients considered fatalistic and spiritual beliefs important barriers to enrollment while non-enrolled patients tended to neither agree nor disagree with these barriers.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios from the logistic regression model and corresponding to a change in one standard deviation in summary scores are presented in Table 4.

| Factorsa | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | P | |||

| Symptomsimprovement | 3.81 | 1.95 | 7.48 | <0.001 | 3.20 | 1.06 | 9.71 | 0.040 |

| Distrust of the medical system | 1.92 | 1.24 | 2.96 | 0.003 | 1.83 | 0.83 | 4.05 | 0.134 |

| Fear/Uncertainty | 1.50 | 0.99 | 2.28 | 0.056 | 3.60 | 1.30 | 9.97 | 0.014 |

| Fatalistic/Spiritual beliefs | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.65 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.001 |

bORs adjusted by ethnicity, education, income, and marital status.

Table 4: Unadjusted and Adjusted Odd Ratios for Selected Dimensions Associated with Enrollment in EPCT.

For one standard deviation increase in the importance given to the possibility of symptoms improvement, the predicted odds of refusing enrollment were 3.20 times greater (OR=3.20, 95% CI=1.06-9.71, p<0.040) holding any other variables in the model constant. Regarding barriers, among patients who considered fear/uncertainty of the new treatment a deterrent to enrollment, one standard deviation increase in agreement with these barriers was associated with a 3.60 increase (OR=3.60, 95% CI=1.30-9.97, p<0.014) in the odds of not being enrolled in an EPCT. In contrast, non-enrolled patients were less likely (OR=0.14, 95% CI=0.05-0.44, p 0.001) to consider fatalistic beliefs as an important barrier to participation.

Subgroup analysis

To assess differences by enrollment status and race/ethnicity, a subset of the data was selected including only white and Latino patients (N=86) (Table 5). Enrolled patients were mostly white (83%) while non-enrolled patients were mostly Latinos (80%). Among promoters to enrollment, even though not large, mean differences between the enrolled and non-enrolled groups were significant for symptoms improvement. Considering potential motivators/promoters to enrollment in EPCTs, Latino patients were more likely than white patients to give great importance to factors related to the possibility that the experimental treatment would: 1) not cause adverse/severe side effects; 2) decrease hospitalization; 3) improve current side effects; 4) increase their ability to be active; and 5) be better than the standard treatment.

| Factors/(min-maxvalues) | Enrollment Status byEthnicity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled(n= 47) | Non Enrolled(n= 39) | |||||||

| Whites (n=39 | Latinos (n=8) | White(n=8) | Latinos(n=31) | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Symptomsimprovement (5-25) | 18.54 | 5.47 | 21.13 | 3.31 | 22.00 | 2.14 | 22.97 | 2.93 |

| Distrust (3-12) | 6.90 | 2.91 | 6.88 | 2.48 | 9.38 | 3.16 | 8.90 | 2.83 |

| Fear/Uncertainty (4-16) | 11.49 | 3.63 | 9.88 | 3.80 | 10.25 | 3.73 | 12.61 | 2.90 |

| Fatalism/Spiritual beliefs (4-16) | 11.39 | 3.21 | 11.13 | 2.59 | 7.50 | 2.62 | 9.26 | 3.53 |

Table 5: Means Comparison of Summary Scores of Promoters and Barriers by Enrollment Status and Race/Ethnicity (N=86).

Regarding factors that would deter their enrollment, there were no differences by ethnicity among enrolled or non-enrolled patients. However, non-enrolled Latinos were more likely than enrolled white patients to agree with barriers related to distrust of the medical system, including distrust of researchers due to prior personal/family experience and language barriers that hamper their communication with their doctor and keep them from clearly understanding the trial purpose and process.

There were no major differences by ethnicity within the enrolled or non-enrolled groups regarding fear and uncertainty of the trial treatment. Despite the similar scores between enrolled and nonenrolled patients, Latinos in the latter group tend to have higher mean scores and agree more that fear and uncertainty of the new treatment is an important barrier in the patients decision to enroll in EPCTs, including: 1) fear of being a guinea pig; 2) fear of sacrificing quality of life; 3) fear of unknown reactions and side effects; and 4) fear that researchers consider the scientific experiment more important than the patient’s health.

Regarding fatalistic attitudes and spiritual beliefs, there were no major differences by ethnicity within enrolled or non-enrolled patients. However, non-enrolled Latino patients were less likely to agree that fatalistic and spiritual beliefs were important barriers to enrollment in an EPCT, compared to their white-enrolled counterparts.

Discussion

Cancer clinical trials are essential to develop new effective treatments and improve cancer patient outcomes and survival. However, the rates of minority patient enrollment in trials, specifically into early-phase clinical trials (EPCTs), continue to be unacceptably low. It has been widely documented that participation of minorities— particularly Latinos—in clinical research is disproportionately low [3,5,7]. In concordance, our study shows that non-enrolled patients were more likely to be Latinos, with lower education and income than the mostly white enrolled patients. This may have implications in terms of message development for traditionally underrepresented groups, which may require clear and easy-to-understand information, with more visual materials, lower reading levels, and more information about financial and other support resources available. It also stresses the importance of a culturally competent medical team with a patientcentered approach to deliver the highest-quality care to every patient regardless of race, ethnicity, culture, or language proficiency.

When enrolled patients were asked how they heard about the EPCT they were participating in, most (86%) responded that their own physician told them about the trial. In addition, all patients responded that the best way to inform patients about available clinical trials was their own physician. This supports prior research [15] and reinforces the vital role that physicians play in successfully recruiting patients to cancer clinical trials, given that they can introduce clinical trials as a treatment option to patients and they are considered a trusted source of health information and advice, particularly for Latinos [15,16]. In addition, patients might be more open to enrollment if physicians are willing to talk with them about clinical research in simple terms and provide clear and easy to understand educational materials in their preferred language preference [39].

Although in the present study both groups tended to strongly agree or agree with all promoting factors and barriers to enrollment, there were significant differences (between white and Latino patients) for one promoter-symptoms improvement-and three barriers related to distrust of the medical system, fear and uncertainty of the trial treatment, and fatalistic attitudes.

Research has shown that while patients understand that personal therapeutic benefit is not the focus of EPCTs, the potential for such therapeutic benefit is one of the most important motivators for participation [19,21]. The present study demonstrates that patients may be motivated to enroll if they perceive that the trial treatment may give them the capacity to control cancer, extending length and quality of life, and obtaining high-quality medical care and follow-up. Good communication about the purpose, potential risks, and benefits of EPCTs with patients who often have exhausted all conventional cancer treatments is difficult [40]. Many patients and their families may have unrealistic expectations about the therapeutic intent of EPCTs, highlighting the importance of developing strategies to aid physicians and patients with these vital conversations [40]. These may include training physicians to enhance their self-efficacy and communication skills to provide clear information about the purpose and process of the EPCT, discuss risks of unknown side effects, provide prognostic information, and verify patients’ understanding of the information provided.

Programs aimed at increasing participation of Latinos in EPCTs need to pay special attention to creating a trusted doctor/patient relationship with a non-intimidating atmosphere, presenting clear and easy-to-understand information about the EPCTs, and the potential risks and benefits for patients and society, as well as the importance of involving the family from the beginning of the recruitment process, preferably in the patient’s language of choice. Socioeconomic barriers are highly important, and some traditionally underrepresented patients may need special assistance with finding financial aid, facilitating access to treatment locations, and making treatment delivery as easy as possible. Patient navigation, as an integral part of a culturally competent healthcare team, is an effective strategy in providing equal access to clinical trials and facilitating patient recruitment and retention by reducing common barriers faced by minority and other underserved cancer patients. Patient navigation may serve as a bridge between the patient and the medical team, addressing communication, cultural and health system issues, and ensuring patients understand the information received to make an informed decision, and won’t get lost in the system.

Fears related to being a research subject were also very important, as well as concerns about sacrificing quality of life. This also highlights the need for physicians to develop a trusting relationship with potential participants and to give them confidence that the treating researchers will respect them and provide the best care possible, regardless of their research interest.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting study results. Non-enrolled patients were patients who rejected a hypothetical invitation to enroll and not actual patients who were invited and refused participation in an EPCT, and therefore may not be comparable. However, their responses provide insight into the minds of people not inclined to participate in EPCTs. Participating patients may not comprise a nationally representative sample, and their responses may differ from those who did not respond to the survey. The small sample size may have limited the power of the study to detect statistically significant differences and associations between the selected predictors and the outcome variable and limited the assessment of interaction effects between enrollment status and ethnicity. In addition, study findings cannot be generalized to the broader community of cancer patients who are enrolled or denied enrollment in EPCTs.

This study also consistently highlighted the importance of physicians documenting whether eligible patients have declined participation in an EPCT and why. This information will help identify where gaps are in trial access and the recruitment process, and determine what strategies to implement to enhance patient enrollment in clinical research.

It has been documented that minority patients, including Latinos, are as willing to participate in clinical research as non-Hispanic whites when eligible and invited to participate [41]. This suggests that efforts to increase accrual of minorities into clinical trials should also focus on ensuring equal access by offering clinical trials as treatment option to eligible patients, while addressing barriers that prevent their participation [41]. Understanding patients’ attitudes might encourage healthcare professionals to willfully approach more of their eligible patients and also help refine the way they discuss relevant trial-related issues that are of most importance to patients, particularly minority patients [42].

The present study, one of the first to identify patients’ barriers to enroll in EPCTs in the predominantly Latino region of South Texas, highlights potential focus areas to increase participation of both minority and non-minority patients in clinical research. More research is necessary to elicit the experiences and opinions of patients who have either agreed or declined to participate in EPCTs to better understand patients’ attitudes and beliefs regarding clinical research, and examine specific factors that promote or hinder their participation. Culturally tailored interventions promoting a patient-centered care and the creation of bilingual culturally competent study teams could solve common barriers and enhance the ability of Latinos to participate in clinical trials. These may simultaneously increase opportunities to involve patients and physicians in clinical trials, while ensuring that the benefits of participation are equitably distributed to patients.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. R21CA101717), the Cancer Therapy & Research Center (Grant No. 2 P30 CA054174-17) and Redes En Acción: The National Latino Cancer Research Network (Grant No. U54CA153511). The authors wish to thank all patients who participated in the survey for sharing their thoughts and experiences with the research team. Special thanks to Drs. Meropol, Pentz, Chamberlain, and Cox for kindly sharing their study questionnaires with us, and to Cliff Despres for his assistance editing the manuscript.

References

- Weissglas-Volkov D, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Nikkola E, Deere KA, Cruz-Bautista I, et al. (2013) Genomic study in Mexicans identifies a new locus for triglycerides and refines European lipid loci. J Med Genet 50: 298-308.

- Weitzel JN, Clague J, Martir-Negron A, Ogaz R, Herzog J, et al. (2013) Prevalence and Type of BRCA Mutations in Hispanics Undergoing Genetic Cancer Risk Assessment in the Southwestern United States: A Report from the Clinical Cancer Genetics Community Research Network. J ClinOncol 31: 210-216.

- Ford JG, Howerton MW, Bolen S, Gary TL, Lai GY, et al. (2005) Knowledge and access to information on recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

- Institute of Medicine (1999) The unequal burden of cancer: An assessment of NIH research and programs for ethnic minorities and the medically underserved. National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

- Institute of Medicine (2010) A national cancer clinical trials system for the 21st century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. National Academies Press.

- Ford E, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Stuart N, Farewell D, et al. (2011) Clinicians’ attitudes towards clinical trials of cancer therapy. Br J Cancer 104: 1535-1543.

- Coalition of Cancer Cooperative Groups (CCCG) (2006) Baseline study of patient accrual onto publicly sponsored trials: an analysis conducted for the Global Access Project of the National Patient Advocate Foundation. Coalition of Cancer Cooperative Groups, Philadelphia, MA.

- Howe HL, Wu X, Ries LA, Cokkinides V, Ahmed F, et al. (2006) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2003, featuring cancer among US Hispanic/Latino populations. Cancer 107: 1711-1742.

- Vélez LF, Chalela P, Ramirez AG (2008) Hispanic/Latino health and disease: An overview. In M. Kline and R. Huff (eds), Health Promotion in Multicultural Populations: A Handbook for Practitioners and Students. (2nd edn). SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh GK, Cardinez C, et al. (2004) Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 54: 78-93.

- Fayter D, McDaid C, Eastwood A (2007) A systematic review highlights threats to validity in studies of barriers to cancer trial participation. J ClinEpidemiol 60: 990-1001.

- Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, et al. (2008) Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer 112: 228-242.

- Houlihan RH, Kennedy MH, Kulesher RR, Lemon SC, Wickerham DL, et al. (2010) Identification of accrual barriers onto breast cancer prevention clinical trials. Cancer 116: 3569-3576.

- Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, Griffith L, Wu P, et al. (2006) Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol 7: 141-148.

- Ramirez AG, Chalela P, Suarez L, Munoz E, Pollock BH, et al. (2012) Early Phase Clinical Trials: Referral Barriers and Promoters among Physicians. J Community Med Health Educ 2.

- Ramirez AG, Wildes K, Talavera G, Nápoles-Springer A, Gallion K, et al. (2008) Clinical trials attitudes and practices of Latino physicians. ContempClin Trials 29: 482-492.

- Tournoux C, Katsahian S, Chevret S, Levy V (2006) Factors influencing inclusion of patients with malignancies in clinical trials. Cancer 106: 258-270.

- Cox K, McGarry J (2003) Why patients don’t take part in cancer clinical trials: an overview of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 12: 114-122.

- Ho J, Pond GR, Newman C, Maclean M, Chen EX, et al. (2006) Barriers in phase I cancer clinical trials referrals and enrollment: five-year experience at the Princess Margaret Hospital. BMC Cancer 6: 263.

- Lara PN, Paterniti DA, Chiechi C, Turrell C, Morain C, et al. (2005) Evaluation of factors affecting awareness of and willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials. J ClinOncol 23: 9282-9289.

- Catt S, Langridge C, Fallowfield L, Talbot D, Jenkins V (2011) Reasons given by patients for participating, or not, in Phase 1 cancer trials. Eur J Cancer 47: 1490-1497.

- Daugherty C, Ratain MJ, Grochowski E, Stocking C, Kodish E, et al. (1995) Perceptions of cancer patients and their physicians involved in phase I trials. J ClinOncol 13: 1062-1072.

- Ellis PM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Dunn SM, Houssami N (2001) Randomized clinical trials in oncology: understanding and attitudes predict willingness to participate. J ClinOncol 19: 3554-3561.

- Kass NE, Sugarman J, Medley AM, Fogarty LA, Taylor HA, et al. (2009) An intervention to improve cancer patients' understanding of early-phase clinical trials. IRB 31: 1-10.

- Meropol NJ, Weinfurt KP, Burnett CB, Balshem A, Benson AB, et al. (2003) Perceptions of patients and physicians regarding phase I cancer clinical trials: Implications for physician-patient communication. J ClinOncol 21: 2589-2596.

- Pentz RD, Flamm AL, Sugarman J, Cohen MZ, Ayers GD, et al. (2002) Study of the media’s potential influence on prospective research participants’ understanding of and motivations for participation in a high-profile phase I trial. J ClinOncol 20: 3785-3791.

- Tomamichel M, Jaime H, Degrate A, De Jong J, Pagani O, et al. (2000) Proposing phase I studies: Patients', relatives', nurses' and specialists' perceptions. Ann Oncol 11: 289-294.

- Weinfurt KP, Castel LD, Li Y, Sulmasy DP, Balshem AM, et al. (2003) The correlation between patient characteristics and expectations of benefit from phase I clinical trials. Cancer 98: 166-175.

- Chamberlain RM, Winter M, Kathryn A, Vijayakumar M, Porter M, et al. (1998) Sociodemographic analysis of patients in radiation therapy oncology group clinical trials. Int J RadiatOncolBiolPhys40: 9-15.

- Cox K (2002) Informed consent and decision-making: patients’ experiences of the process of recruitment to phases I and II anti-cancer drug trials. Patient EducCouns 46: 31-38.

- Lee MM, Chamberlain RM, Catchatourian R, Hiang J, Kopnick M, et al. (1999) Social factors affecting interest in participating in a prostate cancer chemoprevention trial. J Cancer Educ 14: 88-92.

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB (1977) Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 39: 1-38.

- IBM Corporation (2011) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0. IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY.

- Schafer JL, Graham JW (2002) Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 7: 147-177.

- Kaiser HF, Caffrey J (1965) Alpha factor analysis. Psychometrika 30: 1-14.

- Harman HH (1976) Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

- Mayer LS, Younger MS (1976) Estimation of standardized regression coefficients. J Am Stat Assoc 71: 154-157.

- Menard S (2002) Applied logistic regression analysis.Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Avins AL, Goldberg H (2007) Creating a culture of research. ContempClin Trials 28: 557-562.

- Fallowfield LJ, Solis-Trapala I, Jenkins VA (2012) Evaluation of an educational program to improve communication with patients about early-phase trial participation. Oncologist 17: 377-383.

- Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, Van Wye G, Christ-Schmidt H, et al. (2006) Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoSMed 3: e19.

- Jenkins V, Farewell D, Batt L, Maughan T, Branston L, et al. (2010) The attitudes of 1066 patients with cancer towards participation in randomised clinical trials. Br J Cancer 103: 1801-1807.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 17182

- [From(publication date):

June-2014 - Apr 07, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12549

- PDF downloads : 4633