Short Communication Open Access

Prevention of Preterm Birth Redux: Progesterone Works

Tony S Wen and John C Morrison*Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- John C Morrison, M.D.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Mississippi Medical Center

2500 North State Street, Jackson

Mississippi 39216, USA

Tel: 601-984-5376

Fax: 601-984-6904

E-mail: jmorrison@umc.edu

Received date: April 22, 2016; Accepted date: May 22, 2017; Published date: May 29, 2017

Citation: Wen TS, Morrison JC (2017) Prevention of Preterm Birth Redux: Progesterone Works. J Comm Pub Health Nurs 3:173. doi:10.4172/2471-9846.1000173

Copyright: © 2017 Wen TS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

Introduction

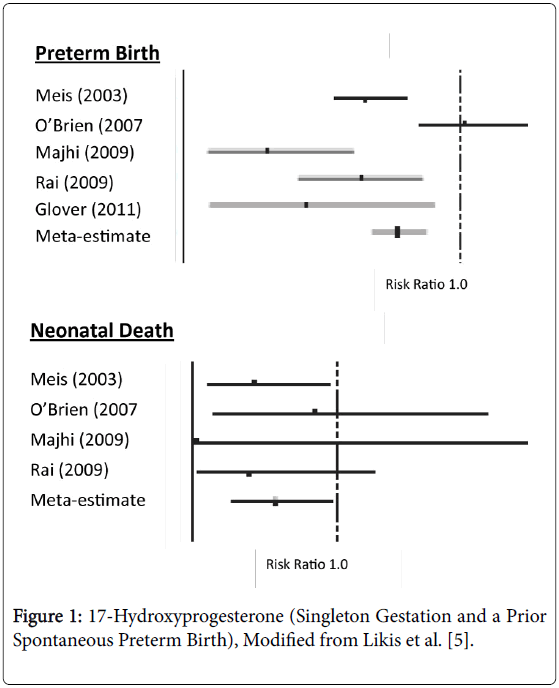

Preterm birth (<37weeks gestation) occurs in approximately 12% of births in the United States and results in 26,000 infant deaths leading to our unenviable rank of 55th in the world for infant mortality [1,2]. Preterm birth is also extremely expensive with an economic cost (2007) of $26.2 billion accounting for approximately 50% of all pregnancy costs [3]. The diagnosis of preterm labor is controversial. Thus acute tocolytic management of uterine contractions once labor has started is difficult and, even if successful, such treatment is not continued long-term [4]. Complicating matters further is that many variables, such as race, age, socioeconomic standing, bleeding, genetics, etc., are not modifiable risk factors. All this has left obstetricians, as well as obstetric nurses/nurse mid-wives, in a difficult position in their attempt to reduce preterm births. However, we have one thing that has been shown to decrease early delivery 17- Hydroxyprogesterone Caproate (17P). The use of 17P (250 mg injected weekly) in women with a singleton pregnancy who have had a prior spontaneous early delivery, revealed a diminution in preterm births in every study (Figure 1) [5]. All of these reports showed a reduction in preterm births (<37 weeks gestation) averaging 22%. Two of the studies also reported a reduction in deliveries below 32 weeks gestation while four of the investigations noted a significant reduction in the neonatal deaths by 42%. Likewise for the studies which reported birthweights among treated patients, they noted neonates were 214-512 g heavier than control off-spring. Progesterone appears to have its salutary effects by several mechanisms. First, progesterone decreases the number of myometrial oxytocin receptors and increases gap junctions. The drug also counteracts prostaglandin production by the amniochorion while enhancing the structural integrities of the cervix [6].

While the idea dose of progesterone is unknown, the lowest percentage of preterm births were seen when the median severe concentration exceeded 6.4 ng/ml [7]. Finally genetic variations also may effect responsiveness to progesterone as noted by Manuck et al. [8].

However, there are certain situations where progesterone treatment is not useful. Schuit et al. [9] showed that the administration of 17P in patient with twins was not helpful in reducing neonatal mortality or morbidity. Briery et al. [10] demonstrated that weekly 17P was not of assistance in prolonging pregnancy or decreasing neonatal morbidity in research subjects who had preterm premature rupture of membranes. In contrast, vaginal progesterone used in patients with a short cervix has demonstrated a reduction in preterm births as well as composite neonatal morbidity [11]. Also, it appears that 17P injections may be helpful in prolonging pregnancy in women who have arrested preterm labor and then are treated with weekly injections after discharge [12]. What we discuss in this commentary is the use of weekly 17P injection in women with a singleton gestation who have had a prior spontaneous preterm birth.

A recent study by Iams et al. [13] revealed that in clinics of 20 large hospitals in Ohio, over 2500 women eligible for 17P were tracked for almost two years and there was a 13% reduction in births before 32 weeks, which is exactly the group where most of the neonatal morbidity and mortality would occur. The foundation of this successful program emphasizes early access to prenatal care, consistent counselling regarding early recognition of preterm labor, adopting a cervical length sonography screening program as well as expediting weekly progesterone supplementation and customizing the start of such treatment in each case. Although 17P is almost universally available for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients, as well as patients with commercial insurance, many appropriate candidates do not receive 17P therapy for a variety of reasons. For example, Orsulak et al. [14] found in Louisiana that while 9.9% of pregnant women covered by Medicaid in that state were eligible (prior spontaneous preterm birth) only 7.4% of that group received weekly 17P. In addition, only half of them received ≥ 10 weekly injections of 17P. Similarly, Stringer et al. [15] noted that in two large hospitals in North Carolina over a two-year period, 627 women had a history of a prior spontaneous preterm birth but only 296 were treated (47%) and many of those only received one or two doses of 17P. In Mississippi, despite universal availability of 17P, patients receiving weekly injections is estimated to be around 15% [16].

There are a myriad of reasons why patients requiring 17P to prevent preterm births are not effectively treated. Recently, Turitz et al. [17] studied this question in 243 women who were candidates for 17P injections. They noted the women (74.7%) attending their preterm birth clinic, staffed by nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, and obstetricians, who received the drug were more likely have a history of a second trimester loss, a short cervical length, or a recent preterm birth. Those women with a prior full-term birth (particularly if it followed their early delivery) were less likely to accept 17P treatment. In this study, race, obesity and insurance status did not impact 17P usage. Nurse and physician providers who counseled patients on each prenatal visit about the importance of preterm birth and universal access to 17P were the most consistent predictors of appropriate treatment for eligible women.

Another issue that thwarted the 17P initiative was the type of 17P used. Initially 17P was compounded by local pharmacies. Once the FDA approved Makena® (2011, manufactured by KV Pharmaceuticals and marketed by Ther-Rx) the issue was the high cost ($1500 per dose) [18]. This predatory pricing eventually resulted in bankruptcy for these companies. More recently, Makena™ has been marketed by AMAG Pharmaceutical company. Commercial insurance payors as well as Medicaid plans, have accepted this AMAG structure as cost effective. Compounded 17P products, while less expensive, have significant safety issues. (Table 1) as noted after the several deaths after epidural steroid injections [19]. Accordingly, the FDA Advisory Committee has recommended that “The FDA product, Makena®, should be used instead of a compounded drug except when there is a specific medical need (e.g. allergy) that cannot be met by the approved drug” [20]. In summary, the issue of cost effectiveness and reliability of the type of 17P to be used for such patients have become a moot point.

| FDA Drugs | Compounded Drugs |

|---|---|

| Proven efficacy/safety | Not tested for efficacy/safety |

| Assayed for purity/quality | Tests for purity/quality inconsistent |

| Standard labeling/prescribing information | Absent standard labeling/prescribing information |

| Adverse event reporting required | Adverse events not collected or reported |

| Manufactured in FDA-regulated and GMP*-complaint facilities | Exempt from GMP*, no facility inspections required |

Table 1: Manufacturer of pharmaceuticals, *GMP: Good Manufacturing Practices.

There are other challenges. Many Medicaid patients who need 17P, register late for prenatal care. Although 17P used in women with prior preterm birth is recommended to start treatment between 16–20 weeks; earlier than some women begin prenatal care. However, there are several studies supporting the initiation of such treatment in appropriate patients as late as 28 weeks [21,22]. In these studies, women so treated had a reduction in births <35 weeks in 26.4% compared to 41.7% in the control group as long as treatment was initiated by 28 weeks’ gestation [22]. Also, the AMAG Pharmaceutical Company has a “quick start program” which, in women who must qualify for Medicaid (which can take 4-6 weeks), covers the injections until Medicaid approval. There is also has a robust patient assistance program that covers Makena® injections for those unable to obtain it any other way. A case management program that provides a higher level of patient compliance in health care areas lacking discreet preterm birth prevention programs is key. Lucas et al. [23] revealed in Centene’s managed program developed for women at risk for preterm delivery (which involved patient education, weekly home visits and 24-7 telephone nurse access) that almost 60% of 790 patients initiated 17P early in prenatal care (16-20 weeks). Of the 10,583 injections administered 97.5% were given within the recommended injection intervals of 6 to 10 days. Most recently Rittenberg [24] have expanded their experience comparing patients without case management (2004-2006, n=1979) and women in a case management system (2007-2010, n=10,695). There were fewer spontaneous preterm births (p-0.001) and the elective discontinuation rate between 34-36 weeks was significantly decreased (26.9% vs. 16%, p=0.001) [24]. Finally, since child care and transportation among other issues are challenges for weekly injections in the medical clinic, a home administration program would be helpful. These initiatives will require the involvement of nurse providers of every type. Accordingly, nurse participation in several studies has shown better results compared to treatment in physician offices or even in university specialty clinics. For example, Gonzalez-Quintero et al. [25] found that there was an earlier registration, increased compliance with injections, more injections administered and less early termination of weekly treatments (before 34 weeks) when injections were given by the home nurse. A comparison of results underscored fewer preterm birth, greater gestational age at delivery and less neonatal morbidity in those who had home injections compared to the control group [26].

In addition to the pharmaceutical industry’s contributions, medical providers can offer specific education programs to enhance patient participation. An alignment of physician’s offices with best practice guidelines and common protocols could be helpful in assisting consistent nursing practice in the administration of 17P. Likewise, telemedicine can offer expert consultation as well as sonographic interpretation. Education of physicians, nurse practitioners and nurse midwives through programs on a state or regional basis could establish the validity of the management protocols regarding 17P, as well as other strategies for preterm birth prevention. A campaign to highlight the advantages of 17P by presenting at local, state and regional meetings, as well as national meetings for nurses and physicians could be helpful. Finally, we need to consider other novel solutions. One such effort which Orsulak et al. [14] begin in Louisiana is a pay-forperformance strategy where managed care organizations do not receive their full payment for delivery unless 17P is administered to appropriate women. A national initiative has been proposed by the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine where national organizations such as the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology might partner with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to support similar same pay-for-performance strategies for 17P. Also, professional liability may play a role as malpractice suits against physicians, nurses and hospitals, related to the failure to administer 17P when a preterm birth does occur, are becoming more common. Medial liability insurers in many areas are providing education for their members and in some cases, reducing premiums for compliance.

It is critical for all of us (physicians, nurses, nurse mid-wives educators and payors) to be consistent in prenatal care ensuring that women with a singleton pregnancy who have had a prior spontaneous preterm birth receive weekly 17P injections at the earliest possible times (preferably 16–20 weeks) continue them up to 36 weeks. For over 50 years we have looked for something that will help decrease the incidence of preterm births (particularly those <32 weeks) and now we have found such a tool in 17P. Our challenge is to make certain all appropriate women receive this treatment as they deserve nothing less than the best care we have to offer.

References

- Hamilton BE, Marin JA, Osterman MJK, Curtin CS, Matthews TJ (2014) Births: Final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep 64: 1-64.

- American College of Nurse-Midwives, Division of Standards and Practice, Clinical Standards and Documents Section. ACNM position statement on preterm labor and preterm birth.

- Schoen CN, Tabbah S, Iams JD, Caughey AB, Berghella V (2015) Why the United States preterm birth rate is declining. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213: 175-180.

- Haram K, Mortensen JH, Morrison JC ((2015) Tocolysis for acute preterm labor: Does anything work. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 28: 371-378.

- Likis FE, Edwards DR, Andrews JC, Woodworth AL, Jerome RN, et al. (2012) Progestogens to prevent preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 120: 897-903.

- Di Renzo GC, Rosati A, Mattei, Gojnic M, Gerli S (2005) The changing role of progesterone in preterm labour. BJOG 112: 57-60.

- Caritis SN, Venkataramanan R, Thom E, Harper M, Klebanoff MA, et al. (2014) Relationship between 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate concentration and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210: 128-126.

- Manuck TA, Watkins S, Moore B, Esplin MS, Varner MW et al. (2014) Pharmacogenomics of 17-alph hydroxyprogesterone caproate for recurrent preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210: 321.e1-321.e21.

- Schuit E, Stock S, Rode L, Rouse DJ, Lim AC, et al. (2014) Effectiveness of progestogens to improve perinatal outcome in twin pregnancies: An individual participant data meta-analysis. BJOG 122: 27-37.

- Briery CM, Veillon EW, Klauser CK, Martin RW, Magann EF, et al. (2011) Women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes do not benefit from weekly progesterone. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204: 54.e1-5.

- Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee (2012) Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am Obstet Gynecol 206: 376-386.

- Briery CM, Klauser CK, Martin RW, Magann EF, Chauhan SP, et al. (2014) The use of 17-hydroxy progesterone in women with arrested preterm labor: A randomized clinical trial. J Maternal Fetal Neonatal Med 27: 1892-1896.

- Iams JD, Applegate MS, Marcotte MP, Martha R, Michael AK, et al. (2017) A statewide progestogen promotion program in Ohio. Clinical practice and quality. Obstet Gynecol 129: 339-346.

- Orsulak MK, Block-Abraham D, Gee RE (2015) 17 alpha-hydroxprogesterone caproate access in the Louisiana medial population. Clinical Therapeutics 37: 727-732.

- Stringer EM (2016) 17-Hydroxprogesterone Caproate (17P) Coverage among eligible women delivering at two north Caroline hospitals in 2012 and 2013: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 215: 105.e1-105.e12.

- Bofill JA, Collier CH, Pearson M, Shwayder JM, Morrison JC (2016) Reducing barriers to 17-hydroxprogestrone caproate (17P) injections to prevent recurrent preterm birth in Mississippi. J MSMA 57: 350-353.

- Turitz AL, Bastek JA, Purisch SE, Elovitz MA, Levine LD (2016) Patient characteristics associated with 17-apha hydroxprogesterone caproate use among a high-risk cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214: 536.e1-5.

- Cohen AW, Copel JA, Macones GA, Menard MK, Riley L, et al. (2011) Unjustified increase in cost of care resulting from U.S. food and drug administration approval of Mekana (17P). Obstet Gynecol 117: 1408-1412.

- Gudeman J, Jozeiakowski M, Chollet J, Randell M (2013) Potential risks of pharmacy compounding. Drugs RD 13: 1-8.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2012) January 20, 2012: Reproductive health drugs advisory committee meeting announcement.

- Gonzales-Quintero VH, Istwan NB, Rhea DJ, Smarkisky L, Hoffman MC, et al. (2007) Gestational age in initiation of 17P and recurrent preterm delivery. J Mat Fetal Neonat Med 220: 249-252.

- Mason MV, Poole-Yaeger A, Krueger CR, House KM, Lucas B (2010) Impact of 17P usage on NICU admissions in a managed medicaid population-A five year review. Manag Care 19: 46-52.

- Lucas B, Poole-Yaeger A, Istwan N, Stanziano G, Rhea D, et al. (2012) Pregnancy outcomes of managed Medicaid members prescribed home administration of 17 a-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. AM J Perinatol 27: 489-496.

- Rittenberg C (2011) Improvement in appropriate use of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate in the community setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol 104: S56.

- Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Istwan N, Tudela FJ, Rhea D, Romary LM, et al. (2011) Conformity with treatment standards and pregnancy outcomes in patients receiving 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) for preterm birth prophylaxis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 176: S81.

- Gonzales-Quintero VH, Tudela FJ, Cordova Y, Romary L, Rhea D, et al. (2012) Rates of preterm delivery in women receiving nurse administered 17P in a home vs. office setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol 157: S82.

Relevant Topics

- Chronic Disease Management

- Community Based Nursing

- Community Health Assessment

- Community Health Nursing Care

- Community Nursing

- Community Nursing Care

- Community Nursing Diagnosis

- Community Nursing Intervention

- Core Functions Of Public Health Nursing

- Epidemiology

- Epidemiology in community nursing

- Health education

- Health Equity

- Health Promotion

- History Of Public Health Nursing

- Nursing Public Health

- Public Health Nursing

- Risk Factors And Burnout And Public Health Nursing

- Risk Factors and Burnout and Public Health Nursing

Recommended Journals

- Epidemiology journal

- Global Journal of Nursing & Forensic Studies

- Global Nursing & Forensic Studies Journal

- global journal of nursing & forensic studies

- journal of community medicine& health education

- journal of community medicine& health education

- Palliative Care & Medicine journal

- journal of pregnancy and child health

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3830

- [From(publication date):

May-2017 - Jul 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 2938

- PDF downloads : 892