Prevalence and Characteristics of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Among Pregnant Women Seeking Antenatal Care, Solomon Islands (2016)

Received: 18-Sep-2017 / Accepted Date: 25-Sep-2017 / Published Date: 28-Sep-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000558

Abstract

Introduction: Violence against women by partners during pregnancy is a major public health concern. As there is no studies done in the Solomon Islands to date on the prevalence of Intimate partner violence (IPV) specifically in the pregnant population, this study is aimed to understand the prevalence and characteristics of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) among pregnant women seeking antenatal care, Solomon Islands (2016).

Methodology: This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at the National Referral Hospital (NRH) in Solomon Islands. Data was collected in 2016 using a valid questionnaire. A purposive sampling was used. An interviewer administered structured questionnaire was used in health facilities after participants approval. Participants were given an open invitation and those who volunteered to take part in the study were provided with a participant information sheet. Written informed consent was obtained before administration of the questionnaire. Data were analysed using SPSS and the results were shown in table and graph.

Results: 242 women met the study criteria. Participants’ age ranged from 16 to 44 years with a mean of 28 years. 55% have had one or more pregnancy and 222 (92%) had their antenatal booking in the second or third trimester. Out of the total participants, 136 (56%) reported experiencing IPV in pregnancy. The prevalence of emotional, sexual and physical IPV was 45%, 33% and 17% respectively. The results also showed that 92% of women who reported experiencing violence in the current pregnancy didn’t received any form of counseling.

Conclusion: Demographic characteristics of participants and also high prevalence of IPV as shown in this study highlight this issue as an urgent health priority for the policy makers and health decision makers. Using the results of this study to develop an interventional study can be suggested.

Keywords: Prevalence; Intimate partner violence; Pregnant women; Solomon Islands

8598Introduction

One of the most common forms of violence against women is that performed by a husband or an intimate male partner [1]. Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship [2,3].

Violence against women by partners during pregnancy is a major public health concern [4]. It can cause physical and psychological harm to women, and lead to pregnancy complications and poor outcomes for babies [5]. In addition, evidence from prevalence studies that the ‘high prevalence of IPV in pregnancy has made it more common than some maternal health conditions routinely screened for in antennal care’ is really a concern [6,7]. The prevalence of IPV in pregnancy ranged from 1%-20%, depending on the way IPV is assessed and the population studied [8]. The WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women has found the prevalence of physical IPV in pregnancy was ranged between 1% in Japan to 28% in Peru, while the majority of the other countries surveyed showed a range between 4% and 12% [9].

Population studies 2-4 carried out in the Pacific found Solomon Islands (SI) to be one of the countries with a high prevalence rate of IPV [10-12]. As part of the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women, the Solomon Islands Family Health and Safety Study (SIFHSS) that was carried out by the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) showed that 64% of ever partnered women aged 15-49 have reported experiencing physical or sexual violence, or both by an intimate partner. Of women who have ever been pregnant, 11% reported being beaten during pregnancy [12].

It is well documented that women’s experience of IPV during pregnancy is associated with both maternal and fetal adverse health outcomes. As there is no studies done in the Solomon Islands to date on the prevalence of IPV specifically in the pregnant population, this study is aimed to understand the prevalence and characteristics of Intimate Partner Violence among pregnant women seeking antenatal care, Solomon Islands (2016).

Methodology

This is a cross-sectional descriptive study which is conducted at the National Referral Hospital (NRH) in Solomon Islands. The NRH currently has an annual total of 5,800 deliveries and this captures women from Honiara’s antenatal population as well as referrals from other provinces. Data was collected from 2nd May to 31st May 2016. All pregnant women irrespective of their gestational age and the number of visits to each clinic were eligible for the study. Women who did not volunteer to participate were excluded from the study.

A structured questionnaire has been developed by WHO was used in this study. The questionnaire was translated into pidgin, the commonly used local language. A pilot study was conducted after translating the questionniare engaging 15 participants who met the study inclusion and exclusion criteria to measure the face validity of the questionnaire. It helped us to find the readability and understandability of the questionnaire by the participants. The data collection instrument included variables related to social and demographic characteristics of the pregnant women, maternal reproductive history and the women’s history of their experience of IPV. Participants were given an open invitation and those who volunteered to take part in the study were provided with a participant information sheet. Written informed consent was obtained before administration of the questionnaire. Interviews were conducted in private within the health facilities by a trained interviewer.

Data were analysed using SPSS (version 22) and descriptive analysis of variables was done to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the women. Prevalence of women reporting the different forms of IPV in pregnancy was calculated. Approval to do the study was sought from the College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences’ (CMNHS) Health Research of Fiji as well as the Solomon Islands National Health Research Ethics committee.

Results

We recruited a total of 242 women from which the final analysis was based on. Of the total participants, 71 (36%) were interviewed while they were attending antenatal clinic at the National Referral Hospital and 171 (64%) were interviewed while they were attending antenatal clinic at the other feeder facilities namely Kukum, Mataniko and Rove clinics. Participants’ age ranged from 16 to 44 years with a mean of 28 years. Table 1 shows participant’s socio-demographic characteristics. 221 (91%) were currently or ever married, 205 (85%) have attended secondary and lower education and 156 (64%) were unemployed. A further 134 (55%) have had one or more pregnancy and 222 (92%) had their antenatal booking in the second or third trimester.

| Variable | Total (%) | IPV reported (n, %) | No IPV reported (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age (years) | |||

| Less than 20 | 15 (6) | 8 (53) | 7 (47) |

| 20 or more | 227 (94) | 128 (56) | 99 (44) |

| Marital status | |||

| Currently/Ever married | 221 (91) | 130 (59) | 91 (41) |

| Single | 21 (9) | 6 (29) | 15 (71) |

| Woman’s education level | |||

| Secondary and lower | 205 (85) | 115 (56) | 90 (44) |

| Higher education | 37 (15) | 21 (57) | 16 (43) |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 156 (64) | 86 (55) | 70 (45) |

| Employed | 86 (36) | 50 (58) | 36 (42) |

| History of smoking | 39 (16) | 27 (69) | 12 (31) |

| Contraceptive use | 57 (24) | 34 (25) | 23 (22) |

| Planned pregnancy | 139 (57) | 84 (62) | 55 (52) |

| Parity | |||

| Multipara | 134 (55) | 74 (55) | 60 (45) |

| Primi/nullipara | 108 (45) | 62 (57) | 46 (43) |

| Booking gestation | |||

| First trimester | 20 (8) | 8 (6) | 12 (11) |

| Second/third trimester | 222 (92) | 128 (94) | 94 (89) |

Table 1: Frequency for socio-demographic variables for women reporting violence in pregnancy and those not reporting violence in pregnancy (N=242).

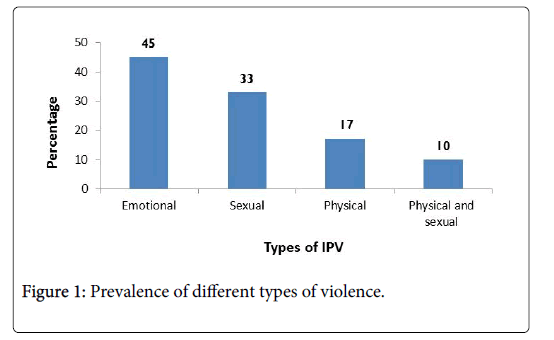

Out of the total participants, 136 (56%) reported experiencing IPV in pregnancy, while 106 (44%) did not report any violence from a partner when they were pregnant. Among women with a history of IPV in pregnancy (n=136) the prevalence of overall, emotional, sexual, and physical IPV was 56%, 45%, 33% and 17% respectively. A further 10% had reported experiencing both physical and sexual IPV (Figure 1).

Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of the different forms of violence reported. Emotional abuse (45%, n=109) was the most common form of IPV during pregnancy followed by sexual abuse (33%, n=79), physical abuse (17%, n=41) and a combination of physical and sexual abuse (10%, n=24). Women who reported experiencing violence in the current pregnancy were asked if they have received any form of counseling, and the majority (92%) said that they did not. When the same women were further asked about the reasons why they did not receive any counseling, almost ¾ of them (74%) mentioned that they were not aware of the availability of such services. A good proportion (19%) had other reasons and interestingly some have given the reason that ‘it did not bother them’ even though they were aware that such services are available.

Discussion

The results of the study highlighted that more than half of participants (56%) reported experiencing IPV in pregnancy and the prevalence of emotional, sexual and physical IPV was 45%, 33% and 17% respectively. The results also revealed that 92% of women who reported experiencing violence in the current pregnancy didn’t received any form of counseling.

The Solomon Islands Family Health and Safety Study (SIFHSS) reported only physical IPV during pregnancy that was 11% which is considerably lower than that found during the period of this study (56%). This rate is more consistent with that found in the general population (64%) according to the SIFHSS [12]. The rate of IPV in pregnancy from our study is also higher than that found in other Pacific population studies [10,12,13] which similarly to the SIFHSS have only measured physical violence during pregnancy.

Several studies were done in the Pacific which utilised the WHO multi-country study methodology [12,13]. The SIFHSS showed that 64% of ever partnered women aged 15-49 reported experiencing physical or sexual violence, or both by an intimate partner [12]. Of women who have ever been pregnant, 11% reported being beaten during pregnancy [12]. Similar studies 3,4 carried out in Samoa and Kiribati showed the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy to be 10% and 23% respectively [14,15], whereas in Vanuatu it was found to be 15% [16]. In Fiji according to a survey done by the Fiji Women’s Crisis Centre, 64% of women who have ever been in an intimate relationship have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a husband or intimate partner in their lifetime and 15% have been beaten during pregnancy [17].

The pattern of occurrence of the different types of violence as shown in this study is consistent with that found among the general population of women according to the SIFHSS with emotional violence being the commonest, followed by sexual and physical violence [12]. Although we did not specifically measure past IPV to compare violence in pregnancy and outside pregnancy in our study, it can be seen that physical violence is less common compared to emotional and sexual violence. The SIFHSS revealed women had reported that violence was less severe during pregnancy, indicating it may be a protective time. It is worth noting that the poor use of contraceptives generally in Solomon Islands women needs further work to explore whether women resort to pregnancy as a protective mechanism from partner violence. The high rates of non-physical forms of violence and lower rate of physical violence according to Shamu et al. ‘may be an indication of men reducing this type of abuse during pregnancy because of the value they place on the unborn child whilst forcing sex and emotional abuse are not perceived in the same way’ [18].

We have asked women experiencing violence in the index pregnancy whether they received any form of counseling at any stage during their pregnancy, and the majority (92%) mentioned that they did not receive any counseling. Almost three fourth of the women (74%) gave the reason that they were not aware of the availability of such services. This shows a general lack of women’s knowledge of support services available for IPV victims even among urban women, which is the likely reason for their poor utilization. The SIFHSS also found that one of the reasons why women with IPV don’t seek help is because they ‘don’t know’ [12].

Conclusion

However, this study is the first study conducted in Solomon Islands, it had some limitations such applying purposive sampling which may not be fully representative of the antenatal population studied and there is a high chance of researcher bias due to lack of randomisation.

References

- Heise L, Moreno CG (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization. Geneva. 87-121.

- AlfonsoP, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburúa E, et al. (2006) The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women's mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. J Womens Health15: 599-611.

- Jewkes R (2002) Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. Lancet359: 1423-1429.

- Sarkar N (2008) The impact of intimate partner violence on women's reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J ObstetGynaecol28: 266-271.

- Jahanfar S, Janssen PA, Howard LM, Dowswell T (2013) Interventions for preventing or reducing domestic violence against pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev28: CD009414.

- Devries KM, Kishor S, Johnson H, Stöckl H, Bacchus LJ, et al. (2010) Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reprod Health Matters18: 158-170.

- Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, Tancredi DT,Levenson RR, et al (2010) Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contracept81: 316-322.

- Bailey BA (2010) Partner violence during pregnancy: Prevalence, effects, screening, and management. Int J Womens Health2: 183.

- Moreno GC, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C (2005) WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (2013) Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva.

- FuluE, Jewkes R, Roselli T, Moreno CG (2013) Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health1: 187-e207.

- Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2009) Solomon Islands family health and safety study: A study on violence against women and children. Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) report.

- Pallitto CC, GarcÃa-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Heise L, Ellsberg M, et al. (2013) Intimate partner violence, abortion, and unintended pregnancy: Results from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Int J GynecolObstet120: 3-9.

- Pacific WomenShaping Pacific Development (2006) The Samoa family health and safety study. Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC).

- Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2010) Kiribati family health and support study.A study on violence against women and children.

- Vanuatu Women’s Centre (2011) Vanuatu national survey on women’s lives and family relationships.

- Fiji Women’s Crisis Center (2013) National research on women's health and life experiences in Fiji (2010/2011). Pacific WomenShaping Pacific Development.

- Shamu S, Abrahams N, Zarowsky C, Shefer T, Temmerman M (2013) Intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Zimbabwe: A cross?sectional study of prevalence, predictors and associations with HIV. Trop Med Int Health18: 696-711.

Citation: Koete B, Nusair P, Mohammadnezhad M, Khan S (2017) Prevalence and Characteristics of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Among Pregnant Women Seeking Antenatal Care, Solomon Islands (2016). J Community Med Health Educ 7: 558. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000558

Copyright: © 2017 Koete B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5425

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Jul 05, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4518

- PDF downloads: 907