Research Article Open Access

Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Anemia among Pregnant Women in Rural Part of JigJiga City, Eastern Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Study

Solomon Gebretsadik Bereka1*, Adunga Negussie Gudeta1, Melese Abate Reta2 and Lemessa Assefa Ayana1

1Department of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Jig-jiga University, Ethiopia

2Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Health Science, Woldia University, Ethiopia

- Corresponding Author:

- Solomon Gebretsadik Bereka

Department of Public Health

College of Medicine and Health Sciences

Jigjiga University, Ethiopia

Tel: 251949320147

E-mail: solomonbereka@gmail.com

Received date: June 07, 2017; Accepted date: June 19, 2017; Published date: June 24, 2017

Citation: Bereka SG, Gudeta AN, Reta MA, Ayana LA (2017) Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Anemia among Pregnant Women in Rural Part of JigJiga City, Eastern Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Study. J Preg Child Health 4:337. doi:10.4172/2376-127X.1000337

Copyright: © 2017 Bereka SG, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health

Abstract

Background: Anemia prevalence varies by place of residence ‒ a higher proportion of women in rural areas are anemic as compared to those in urban areas. The main objective of this study was to identify and analysis the prevalence and associated risk factors of anemia among pregnant women in rural part of Jigjiga city, eastern Ethiopia. Method: Among 417 pregnant women, a cross-sectional study was done from August to December 2015. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data related to socio-demographic characteristics, medical, obstetric and dietary practices. Haemoglobin levels of pregnant women were determined by applying HemoCue photometer. Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS-version 21. Result: Of the total respondent 63.8% were anemic. The multiple logistics regression analysis showed that gravidity (AOR=2.07; 95% CI: 1.30-2.91); mother’s age (AOR=2.4; 95% CI: 0.01-4.06); family size (AOR=2.12; 95% CI: 1.11-3.31); third trimester (AOR=2.1; 95% CI: 1.07-5.04); iron supplementation (AOR=1.30; 95% CI=1.01-4.01); mid-upper arm circumference of less than 23 (AOR=0.57; 95% CI: 0.20-0.89) and body mass index (AOR=2.03; 95% CI: 2.00-3.81) were significant predictors associated with anemia among pregnant women. Conclusion: Based on World Health Organization (WHO) in the study area anemia was a major public health problem (prevalence greater than 40%). Hence, we recommended that nutritional education and also education about risk factors of anemia should be done.

Keywords

Anemia; Logistic regression; Prevalence of anemia; Risk factors

Introduction

Anemia is a disease which characterized by a low level of haemoglobin in the blood. In turn haemoglobin is a bio-pigment found in red blood cells which used to transporting oxygen from lung to different organs of our body. Anemia in pregnant women may lead to different problems such as premature delivery and low birth weight [1].

Many studies found that anemia in pregnant women depend on many risk factors. For instance, mother’s age, number of pregnancy, soci-economics status and trimester as potential risk factors of anemia. In determining their anemia status haemoglobin (Hb) concentration in the blood is the most dependable pointer [2].

Anemia is worldwide disease Even though women and under-five children are mostly affected by anemia; it can also touch all individual at any stage of life. The prevalence among these two groups is high in developing and also in developed countries [3].

Anemia globally affected 1.62 billion people. Of these, 56 million anemia cases were found in pregnant women [4]. In relation to maternal mortality, anemia contributed to 115,000 deaths per year [5].

When we come to the developing world, anemia prevalence is estimated to be 43%. A 30% of total global cases were found in Sub- Saharan Africa [6].

Ethiopia in general, and in Somali region in particular anemia is a public health problem. This can be seen from Ethiopian demography and health survey [1] 17% of Ethiopian women and 44% of women from Somali region of age 15-49 are anaemic. The report further indicated that anaemia prevalence is high in rural area (18%) than in urban (11%).

Even though anemia in pregnant women well studied, they mainly focused on urban areas. Since prevalence is high in rural that in urban areas, investigation of anemia determinants is paramount important. Moreover, the Somali region is characterized by high prevalence of anemia (p=44%) [1]. Thus, the main objective of this study was to identify and analysis the prevalence and associated risk factors of anemia among pregnant women in rural part of Jigjiga city, eastern Ethiopia.

Methods

Area of study

The rural parts of Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia district have three Health Center namely Harorese, Dadi and Kochara. Of these Harorese Health Center which is 30 km far from the town was selected for this study. It was selected due to the only health center which diagnosis anemia fully.

Study period and design

Facility based survey was conducted from 1st of August to 31st of December, 2015.

Sample size

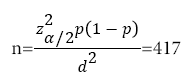

The required number of pregnant women for study was obtained as:

where anemia prevalence (p)=44% [1], α=5% (z_(α/2)^2=3.8416), d=5%, NNR=10%.

Study subject

The study subjects were pregnant women in the rural area of Jigjiga town that fulfil the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Pregnant women of all trimesters, who were able and voluntary to provide information, were included.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant women have anaemia diagnose of anaemia and severely ill.

Data collection method

Socio-demographic and clinical data

Structured questionnaires were used to obtained information related to socio-demographic characteristics, medical, obstetric and dietary practices. The questionnaire was initially developed in English and then translated into the local language (i.e., Somali language). To ensure validity, the questionnaire was retranslated back to English. The data collectors were BSc holder health professionals. Before proceeding to data collection, training was given to the collectors for quality assurance purposes. The principal investigator had supervised the data collection process.

Method for Anaemia diagnosis and status determination

The methods that are generally recommended to determine the anemia status in rural surveys with insufficient infrastructure are the cyanmethemoglobin method and the HemoCue system. In determining the concentration of haemoglobin in the blood HemoCue system is more preferable and reliable method. Anaemia status of pregnant women is determined by measuring haemoglobin level in the blood.

Data quality assurance

To ensure data quality, the questionnaire was pre-tested and two day long training was given to data collectors. Closer supervision was undertaken during data collection.

Operational definitions

If prevalence of anemia greater than 40% ? major public health problem [7].

If prevalence lies between 20 and 40% ? medium-level public health problem [7].

If prevalence less than 20% ? mild public health problem [7].

Description of variables under study

The response variable

Pregnant women are classified as non-anemic if Hb>11.0 g/dl, mild anemic if the range is 10 to 11 g/dl, moderate anemic if the range is 7 to 10 g/dl and severly anemic if Hb is below 7.0 g/dl [7]. The response variable for this particular study was:

Predictor (explanatory) variables

The explanatory variables to be analysed in this study were grouped as socioeconomic, demographic, dietary, obstetric and gynaecological history related factors (Table 1).

| S/n | Variables and Description | Categories | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Socio-economic | Level of instruction | 0=No formal education; 1=Primary and above |

| Occupation | 0=Housewives; 1=Employed; 2=Farmers/pastoralist/agro-pastoralist; 3=Others | ||

| Marital status | 0=Married; 1=Unmarried | ||

| Water source | 0=Pipe;1=others | ||

| 2 | Demographic | Age | 0=<18; 1=19-24; 2=25-29; 3=30-34; 4= ≥ 35 |

| Last child birth | 0=2 years or less; 1=More than 2 years | ||

| Age at first pregnancy | 0=<20; 1= 20-25; 2= ≥ 30 | ||

| 3 | Dietary and obstetric | Body mass index | 0=Low; 1=Normal; 2=High |

| Red meat/poultry/fish consumption | 0=Yes; 1=No | ||

| Fruit/vegetable consumption | 0=Yes; 1=No | ||

| Iron supplementation before pregnancy | 0=Yes; 1=No | ||

| 4 | Gynecological | Parity | 0=<2; 1=2-4; 2= ≥ 5 |

| Gravidity | 0=<3; 1= 3-5; 2= ≥ 6 | ||

| Gestational age | 0=First trimester; 1=Second trimester; 2=Third trimester | ||

Table 1: Detail description of variables under study.

Statistical models

A logistic regression model was good to fit when the dependent variable has categories outcomes [8,9]. Logistic regression analyses were fitted at bivariate and multivariate level to find out factors associated with anemia status of pregnant women.

Ethical approval

This research was operationalized after obtaining ethical clearance from Jigjiga University, research and ethical review committee and district health bureau. In addition, informed consent obtained from each participant after they informed the aim of the study and tell them they have the right to terminate the interview at any time. All information’s and results was be kept secret/confidential.

Results

Socio-economic, demographic and environmental characteristics of respondents

The ranges of the respondents age was 15 to 39 years, with a mean of 22.9 and a standard deviation of 3.9 years. The mean ages of the mothers currently and at first marriage were 22.9 and 16.5, respectively. The majority of the women in the sample (96.7%) were married. Regarding mothers’ educational level, 301 (72.2%) had no formal education while the remaining (116) were had educational level of primary and above. Of 417 respondents, 113 (27.1%) obtained drinking water from pipe and 398 (95.4%) had agricultural farm land. The average family size, number of pregnancies and number of children of the households were 6.8, 5.91 and 4.21, respectively. About 22% of the women were engaged in agro-pastoral and pastoral activities. Moreover, 36.5% of the responding women were house-wives and 32.2% of them were milk and fuel wood sellers (Table 2).

| Covariates | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of the mother | ||

| <18 | 25 | 6 |

| 18-24 | 251 | 60.2 |

| 25-29 | 121 | 29 |

| 30-34 | 9 | 2.2 |

| ≥ 35 | 11 | 2.6 |

| Mean (SD) | 22.9 ± 3.9 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 403 | 96.6 |

| Unmarried | 16 | 3.4 |

| Educational status | ||

| No formal education | 301 | 72.2 |

| Primary and above | 116 | 27.8 |

| Main activity of the women | ||

| Pastoral | 63 | 15.1 |

| Agro-pastoral | 29 | 7 |

| Milk and fuel wood seller | 134 | 32.2 |

| Housewife | 152 | 36.5 |

| Others | 39 | 9.4 |

| Family Size | ||

| ≤ 2 | 134 | 32.1 |

| 3-4 | 211 | 50.6 |

| ≥ 5 | 72 | 17.3 |

| Age at first marriage (years) | ||

| <16 | 147 | 35.2 |

| 16-18 | 240 | 57.5 |

| ≥ 18 | 30 | 7.2 |

| Land that can be used for agriculture | ||

| Yes | 398 | 95.4 |

| No | 19 | 4.6 |

Table 2: Baseline characteristics of pregnant women in rural part Jigjiga city, eastern

Obstetric, dietary habits and nutritional status of respondents

Majority (87.3) of the pregnant women took rice and spaghetti during pregnancy, whereas 11.8% took maize and sorghum. Of the total studied pregnant women, 134 (32.1%) took food three times a day, whereas 197 (47.2%) took food twice per day. Almost all (98.8%) of the pregnant women drank tea. Of these, 52.9% of them took the same before meal. About 9% of the pregnant women took fruits once a week during pregnancy, whereas 72.9% of them did so less than once per month. Of the total studied pregnant women, 8.4% and 72.9% of them took egg once a week and less than once per month during pregnancy, respectively. Majority (86.3%) of the pregnant women used milk and milk products once per day, whiles 1.2% of them used the same once per week. Regarding iron supplementation, 73.8% of the women used it during their current pregnancy. Nutritional status was evaluated by MUAC. 48 (11.5%) of the pregnant women had MUAC of less than 21cm, 40 (9.6%) had MUAC between 21 and 23 cm and the remaining 329 (78.9%) had MUAC within normal limits (>23 cm). Finally, of the total participants of this study, 135 (32.4%) had a BMI of less than 18.5, 274 (65.7%) had between 18.5 to 24.5 and 8 (1.9%) of them had a BMI of above 25 (Table 3).

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Stable diet | ||

| Rice and spaghetti | 394 | 87.3 |

| Maize and sorghum | 18 | 11.8 |

| Others | 5 | 0.9 |

| Meal frequency | ||

| Three times | 134 | 32.1 |

| Two times | 197 | 47.2 |

| One time | 86 | 20.6 |

| Drinking tea | ||

| Yes | 410 | 98.8 |

| No | 7 | 1.2 |

| Time for drinking tea | ||

| Before meal | 221 | 52.9 |

| After Meal | 196 | 47 |

| Fruit frequency | ||

| Once a week | 37 | 8.9 |

| Twice a week | 16 | 3.8 |

| Once per month | 60 | 14.4 |

| Less than once per month | 304 | 72.9 |

| Egg frequency | ||

| Once a week | 35 | 8.4 |

| Twice a week | 8 | 1.9 |

| Once per month | 70 | 16.7 |

| Less than once per month | 304 | 72.9 |

| Milk and milk product frequency | ||

| More than two times per day | 52 | 12.5 |

| Once per day | 360 | 86.3 |

| Once per week | 5 | 1.2 |

| Iron supplementation | ||

| Yes | 308 | 73.8 |

| No | 109 | 26.1 |

| Nutritional status (MUAC) | ||

| <21 cm | 48 | 11.5 |

| 21-23 cm | 40 | 9.6 |

| ≥ 23 cm | 329 | 78.9 |

| BMI | ||

| ≤ 18.5 | 135 | 32.4 |

| 18.5-25 | 274 | 65.7 |

| 25-30 | 8 | 1.9 |

Table 3: Obstetric, Dietary practice and maternal characteristics of pregnant women rural part of Jigjiga city, eastern Ethiopia, 2016.

Anaemia prevalence of the respondents

A according to World Health Organization pregnant women were considered as anemic if hemoglobin <11.0 g/dl.

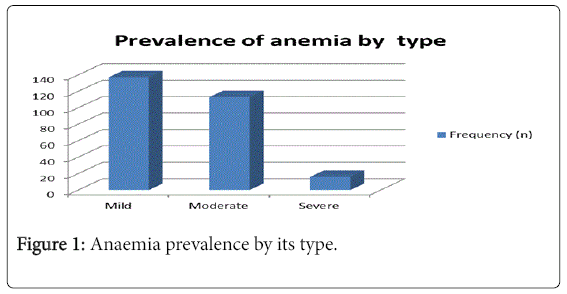

Of the total respondents, 63.8% were anemic. Among this 137 (32.9%), 113 (27.1%) and 16 (3.8%) were mild, moderate and severe anemic, respectively (Figure 1).

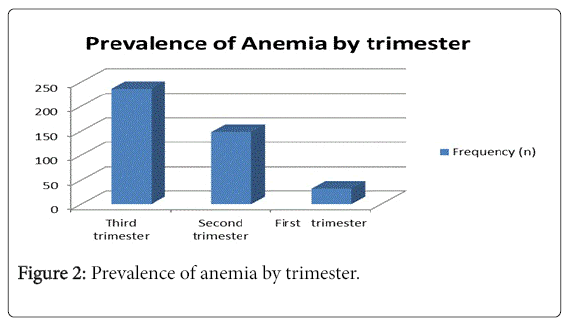

Anemia prevalence was increased as gestational age.

The prevalence in each trimester was obtained as 7.8% in the first, 35.4% in the second and 56.7% in the third trimester, respectively (Figure 2).

Factors associated with anaemia

A fitted logistics regression model showed that pregnant women with age 35 and above were 2.4 (AOR=2.4; 95% CI: 0.01-4.06; Pvalue< 0.007) time more likely to be anemic as compared with those age 18 and less. Pregnant women in third and second trimester were 2.1 (AOR=2.1; 95% CI: 1.07-5.04; P-value<0.009) and 1.2 (AOR=1.2; 95% CI: 1.00-301; P-value<0.005) times more likely to be anemic as compared to those in the first trimester. Pregnant women parity 5 and above were 2.07 (AOR=2.07; 95% CI: 2.00-4.01; P-value<0.003) and 1.07 (AOR=1.07; 95% CI: 1.00-301; P-value<0.001) times more anemic compared to those mothers 1. A pregnant women in a family of size 5 and above and 3-5 were 2.12 (AOR=2.12; 95% CI: 1.11-3.31; Pvalue< 0.004) and 1.50 (AOR=1.50; 95% CI: 1.27-4.01; P-value<0.030) times more likely to be affected by anemia as compared to pregnant women with family size 2 and less. Moreover, pregnant women who were lack of iron supplementation during pregnancy were 1.30 (AOR=1.30; 95% CI=1.01-4.01; P-value<0.000) times likely to develop anemia. In addition, pregnant women who had 3–5 pregnancies were 2.07 (AOR=2.07; 95% CI: 1.30-2.91; P-value<0.002) and 2.00 (AOR=2.00; 95% CI: 1.90-2.91; P-value<0.001) times more likely to be anemic, as compared with those who had less than 3 pregnancies. Similarly, pregnant women with MUAC greater than 23 and between 21 and 23 were 57% (AOR=0.57; 95% CI: 0.20-0.89; P-value<0.000) and 45% (AOR=0.45; 95% CI: 0.09-0.81; P-value<0.000) less likely to developed anemia as compared with those with MUAC<23. Final, pregnant women with BMI less than or equal to 18.5 and 18.5-25 were 2.03 (AOR=2.03; 95% CI: 2.00-3.81; P-value<0.001) and 3.07 (AOR=3.07; 95% CI: 2.90-5.01; P-value<0.000) times more to develop as compared with those with BMI<23 (Table 4).

| Variables | COR (95% CI) | P-value | AOR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||

| <18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 18-24 | 1.9 (0.87-2.01) | 0.874 | 1.8 (0.30-2.07) | 0.761 |

| 25-29 | 2.1 (1.00-5.01) | 0.004 | 1.7 (1.30-2.07) | 0.001 |

| 30-34 | 0.2 (0.01-1.01) | 0.465 | 0.7 (0.30-2.07) | 0.561 |

| ≥ 35 | 1.4 (0.01-1.09) | 0.008 | 2.4 (0.01-4.06) | 0.007 |

| Trimester | ||||

| First | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Second | 0.6 (0.04-0.95) | 0 | 1.2 (1.00-301) | 0.005 |

| Third | 1.4 (1.00-2.09) | 0.01 | 2.1 (1.07-5.04) | 0.009 |

| Parity | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2-4 | 1.8 (1.00-2.01) | 0.05 | 1.07 (1.40-3.01) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 5 | 1.5 (1.00-2.01) | 0.002 | 2.07 (2.00-4.01) | 0.003 |

| Family size | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3-5 | 1.47 (1.02-3.01) | 0.037 | 0.03 | |

| ≥ 5 | 2.10 (1.97-4.76) | 0.005 | 2.12 (1.11-3.31) | 0.004 |

| Iron supplementation during pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1.07 (1.00-2.01) | 0 | 1.30 (1.01-4.01) | 0 |

| Gravidity | ||||

| <3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 03-May | 1.87 (1.30-2.91) | 0.004 | 2.00 (1.90-2.91) | 0.001 |

| ≥6 | 1.03 (1.01-2.06) | 0.005 | 2.07 (1.30-2.91) | 0.002 |

| MUAC | ||||

| <23 cm | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 21-23 cm | 0.17 (0.00-0.81) | 0.032 | 0.45 (0.09-0.81) | 0 |

| ≥ 23 | 0.07 (0.01-0.91) | 0.021 | 0.57 (0.20-0.09) | 0 |

| BMI | ||||

| ≤ 18.5 | 1.47 (1.00-2.01) | 0.047 | 2.03 (2.00-3.81) | 0.001 |

| 18.5-25 | 2.07 (2.00-4.08) | 0.045 | 3.07 (2.90-5.01) | 0 |

| 25-30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 4: Factors associated with anemia among pregnant women in rural part of Jigjiga city, eastern Ethiopia, 2016.

Discussion

Of the total respondents who participated in this study 63.8% were anemic. This result based on WHO [7] anemia is a major public health problem (P>40%). The overall prevalence of anemia obtained in this study was higher than a study conducted in in Arsi, Ethiopia (36.6%) [9], Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (33%) [10] and in Gilgel Gibe, Ethiopia (53.9%) [11]. But it nearly equal with study conducted in Gode, eastern Ethiopia (56.8%) [12], Nigeria (54.5%) [13]. This discrepancy may raise from the current study were considered only pregnant women from the rural side.

Age was found as risk factor of anemia. In this study women age above 35 for first pregnancy highly positively related with anemia. A study conducted by Banerjee [14] in India was also showed that a direct association between age and anemia. This may be as age increase there is chance of losing micronutrient which leads to be less nutrient and be anemic.

The study revealed that age at current pregnancy (trimester) were found to be important variables. As trimester increased the chance for developing anemia was also increased. This result was supported by a study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Rasheed [15] and India by Banerjee [14], which both showed that a high prevalence in the second and third trimester. This may be gestational age increases pregnant women shared their resource with fetus which may expose to decreasing iron.

This study revealed that as parity increased the chance of developing anemia among the respondents increased. For instance, pregnant women with parity 5 and above were highly to be anemic as compared with those with 1. Studies conducted in Kenya [16], Ethiopia [17], Tanzania [18], Egypt [19] and Nigeria [20] in line with this finding. This would be at each delivery there is a loss of blood and which may lead to decrease iron reservation.

In this study family size and anemia revealed a positive relation. For instance, pregnant women with family 4 and above were more likely to be anemic as compared with those with 2 and less. This finding is in opposite when we come to a study conducted in Jordan [21]. The latter showed that, there were no a significant variation between family size and anemia.

The study also revealed that iron supplementation significantly associated with anemia during pregnancy. The chance to be anemic was found to be higher among pregnant women with lack of iron supplementation during pregnancy. Different studies conducted in Ethiopia [12,22], Uganda [23], Nigeria [24], Vietnam [25] and India [14] showed similar finding. This may be for those who taken iron supplementation have a chance to increase a hemoglobin level.

The finding from this study revealed that number of pregnancies (gravidity) was associated with anemia. The odds of developing anemia were higher among women with 5 and above pregnancies as compared with those who had 3 pregnancies. A number of studies Gode [12], Saudi Arabia [15] and India [14] found that a positive relationship between gravidity and anemia. This could be as number of pregnancies and deliveries increased there may be a loss of iron and others basic nutrients increased which lead them to develop anemia.

MUAC and anemia has a negative relationship. For instance from the current study pregnant women with MUAC greater or equal to 23 and between 21 and 23 were less by 57% and 45% risk of developing anemia as compare with less 23. This result is also consistent with a study conducted in Gode [12]. The finding can explained as MUAC less 23 could be less micronutrient and have a higher chance to develop anemia.

The study revealed that pregnant women with less than18.5 body mass index (BMI) were highly exposed to be anemic. Different studies conducted in Ethiopia [17], Tanzania [18] and Egypt [19] which showed that BMI as a significant factors of anemia. The result may be explained as those who had less BMI exposed to be under nutrition, which will lead to develop anemia.

Limitation of the Study

The study was institutional based study. Further study should be conducted based on community level to make this finding stronger.

Conclusion

Based on World Health Organization (WHO) in the study area anemia was a major public health problem (prevalence greater than 40%). Hence, we recommended that nutritional education and also education about risk factors of anemia should be done.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to Jigjiga university and all respondent for their participation this study.

References

- Central Statistical Agency ORC Macro (2012) Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central statistical agency and ORC macro.

- Nik Rosmawati NH, Nazri MS, Ismail M (2012) The rate and risk factors for anemia among pregnant mothers in Jerteh Terengganu, Malaysia. J Community Med Health Educ 2: 5.

- World Health Organization (2008) Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV (2011) Anaemia in low-income and middle income countries. Lancet 378: 2123–2135,

- Sudha S, Vrijesh T, Rajvir S, Harsha S.Gaikwad (2011) Evaluation of haematological parameters in partial exchange and packed cell transfusion in treatment of severe anaemia in pregnancy.

- Demmouche A, Khelil S, Moulessehoul S (2011) Anemia among pregnant women in the Sidi Bel Abbes region (West Algeria): An epidemiologic study.

- World Health Organization (2001) Iron deficiency anemia, assessment, prevention and control. A guide for programme managers Geneva: WHO.

- Hosmer D, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression 2nd ed: NY: Wiley.

- Niguse O, Mossie A, Gobena T (2013) Magnitude of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Shalla woreda, west Arsi zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 23: 165-173.

- Jufar AH, Zewde T (2014) Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. J Hematol Thromb Dis p: 2.

- Getachew M, Yewhalaw D, Tafess K, Getachew Y, Zeynudin A (2012) Anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women in gilgel gibe Dam area, southwest Ethiopia. Parasites Vectors 5: 296.

- Alene KA, Dohe AM (2014) Prevalence of anaemia and associated factors among pregnant women in an urban area of eastern Ethiopia. Anemia.

- Olatunbosun OA, Abasiattai AM, Bassey EA, James RS, Ibanga G, et al. (2014) Prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women at booking in the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria. BioMed Res Int.

- Banerjee B, Pandey GK, Dutt D, Sengupta B, Mondal M (2009) Teenage pregnancy. A socially inflicted health hazard. Indian J Commun Med 34: 227-231.

- Rasheed P, Koura MR, Al-Dabal BK, Makki SM (2008) Anemia in pregnancy: A study among attendees of primary health care centers. Ann Saudi Med 2008, 28: 449-452.

- ufar AH, Zewde T (2014) Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. J Hematol Thromb Dis p: 2.

- Gebremedhin S, Enquselassie F, Umeta M (2014) Prevalence and correlates of maternal anemia in rural Sidama, Southern Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health 18: 44-53.

- Ondimu KN (2000) Severe anaemia during pregnancy in Kisumu district of Kenya: Prevalence and risk factors. Int J Healthc Qual Assur 13: 230-235.

- Morsy N, Alhady S (2014) Nutritional status and socio-economic conditions influencing prevalence of anaemia in pregnant women, Egypt. Int J Sci Technol Res 3.

- Adinma JIB, Ikechebelu JI, Onyejimbe UN, Amilo G, Adinma E (2002) Influence of antenatal care on the haematocrit value of pregnant Nigerian igbo women. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol 19: 68-70.

- L.Al-Mehaisen Y, Khader O, Al-Kuran F, Issa A, Amarin Z (2011) Maternal anemia in rural Jordan: Room for improvement. Anemia, p. 7.

- Hinderaker SG, Olsen BE, Bergsj P, Lie RT, Gasheka P, et al. (2001) Anaemia in pregnancy in the highlands of Tanzania. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 80: 18-26.

- Gebre A, Mulugeta A (2015) Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in north western zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J Nutr Metabol.

- Nwizu EN, Iliyasu Z, Ibrahim SA, Galadanci HS (2011) Socio-demographic and maternal factors in anaemia in pregnancy at booking in kano, northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 15: 33-41.

- Ononge S, Campbell O, Mirembe F (2014) Haemoglobin status and predictors of anaemia among pregnant women in Mpigi, Uganda. BMC Res 7: 712.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 7213

- [From(publication date):

June-2017 - Nov 22, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 5769

- PDF downloads : 1444