Pregnancy and Dental Treatment

Received: 19-Sep-2016 / Accepted Date: 17-Oct-2016 / Published Date: 14-Oct-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000268

Abstract

Background: Pregnancy is accompanied with numerous physiological changes that present oral health consequences. Oral disease during pregnancy has been linked to pre- eclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm birth, low birth weight and stillbirths. Despite evidence-based recommendations regarding the need for dental treatment and counselling of pregnant women, many dentists retain misconceptions regarding dental care during pregnancy and are reluctant in providing necessary dental preventive and curative services. Aim: To assess the beliefs and practices of Lebanese dentists with respect to the dental care of pregnant women. Methods: Self-administered questionnaires were answered by a sample of 195 dentists. Dentists’ knowledge of oral disorders associated with pregnancy in addition to their practices with respect to the administration of radiographs and prescriptions of medications were assessed. Chi-square tests were used to test the association between selected demographic variables and pregnancy-related knowledge outcomes. Results: Fifty-two percent of dentists believed anesthesia was risky for pregnant women and only 55% would take a radiograph when necessary. Only 56% recognized gingivitis as a consequence of pregnancy and 76% recognized the presence of gingival bleeding as a symptom. The majority prescribes analgesics, specifically acetaminophens (90.3%), 73.5% prescribe antibiotics and only 9.2% are willing to prescribe an anti-inflammatory drug. Female dentists (p=0.05) and dentists with greater years of experience (p=0.04) were more aware of the risk of gingival bleeding during pregnancy. Those holding degrees from Lebanese universities were more aware of the association between gingivitis and pregnancy (p=0.03). Conclusion: The knowledge and practices of Lebanese dentists with respect to pregnant women are suboptimal. There is a need to re-assess the dental curriculum and consider the incorporation of training and re-training courses into continuing dental education programs.

Keywords: Pregnancy; Health; Oral health; Dental Treatment

253365Introduction

Oral health is a basic human right that is integral to general health and well-being [1]. Oral diseases such as dental caries, gingivitis and chronic periodontitis are common in all age groups and in vulnerable individuals, particularly in pregnant women who experience numerous physiological changes that present oral health consequences [2-4]. Common symptoms such as gastro-intestinal reflux (acidity), nausea and vomiting result in an acidic oral environment that promotes acid demineralization of tooth enamel and the growth of dental caries pathogens [5-8]. Rising circulation levels of estrogen and progesterone elicit an inflammatory response that predisposes women to a spectrum of pregnancy-related gingival manifestations, including gingivitis, periodontitis, gingival hyperplasia and pyogenic granuloma [5,7]. In fact, pregnancy gingivitis is recognized as a clinically proven reversible manifestation of pregnancy and is estimated to occur in 30 to 100 percent of pregnant women [9-11]. Moreover, the increased susceptibility to infections and reduced ability to repair soft tissue caused by hormonal fluctuations increases the risk of developing periodontitis [12]. Believed to affect 5 to 20 percent of pregnant women, untreated periodontitis results in the loss of alveolar bone and supporting structures and ultimately in tooth loss [13]. Finally, research is increasingly implicating oral disease during pregnancy in the development of complications beyond the pregnant woman’s oral cavity. Periodontal disease, in particular, has been linked to preeclampsia (pregnancy hypertension that poses risk to mother and foetus), gestational diabetes, preterm birth, low birth weight and still births [14-23].

Rather than being a state of disease, pregnancy presents a normal physiological phase in a woman’s lifetime and warrants – at the least – the routine preventive and emergency oral health care provided to other members of the general population.24 Beyond routine dental treatment, the particular relationship between pregnancy and oral health warrants for additional pregnancy-specific preventive care and oral health education [24]. The provision of dental treatment during pregnancy is not only safe, it is also an integral aspect of antenatal care and is advised by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academies of Periodontology and Pediatrics [25-30].

Research consistently highlights the fact that, globally, dentists remain to show hesitation and reluctance towards providing dental treatment to pregnant women despite the availability of detailed evidence-based guidelines [24,25,31-33]. Although there is reason to believe that dental attendance by pregnant women in Lebanon is deficient, there has been no investigation into the attitudes of Lebanese dentists with respect to providing dental care during pregnancy. The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge and attitudes of Lebanese dentists towards the provision of oral health care to pregnant women.

Materials and Methods

This survey was conducted between January and March 2016. It focused on the knowledge attitude and practices of Dentists in treating pregnant women. This methodology had a quantitative character. Based on a review of the literature, a self-administered questionnaire was developed and adopted after being tested on 15 dentists. The selfadministered questionnaire used to collect data was composed of 14 questions organized into 4 categories:

• Demographic variables of the study sample

• Knowledge of dentists about the treatment of pregnant women

• Practices of dentists regarding the treatment of pregnant women

• Prescription of medicines related to dental treatments for pregnant women

The questionnaires were hand-distributed to a convenience sample of 215 dentists and 195 questionnaires were collected and included in the study. The approached dentists were given a choice of either and English or French language questionnaire and were asked to return the questionnaire after answering individually in order to avoid collective answers and peer influence. The questionnaires were anonymous to maintain confidentiality.

Statistical Analysis

Data entry was performed using the software Access (Microsoft Office). Descriptive statistics of the main exposure and outcome variables were generated for the data. The percent distributions of the demographic characteristics of the responding dentists, in addition to the outcomes assessing pregnancy-related knowledge and practices, were generated to present numbers and proportions. Bivariate analysis was used to test the association between selected demographic variables and pregnancy-related knowledge outcomes using Chi Square tests of association. The IBM® SPSS® version 20.0 statistical package was used to carry out all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study sample

The sample included 195 dentists. Out of a total of 215 distributed questionnaires, 195 were returned and were included in the study leading to a response rate of 90%. The sample of dentists was almost equally distributed between genders (51.3% females and 48.7% males). The majority had 10 years of experience or less (56.7%) and held local dental degrees (79.4%; Table 1).

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 100 | 51.30% |

| Male | 95 | 48.70% |

| Total | 195 | 100.00% |

| Years of experience | ||

| 10 years or less | 110 | 56.70% |

| 11- 20 Years | 40 | 20.60% |

| > 20 Years | 44 | 22.70% |

| Total | 194 | 100.00% |

| Origin of diploma | ||

| Lebanon | 150 | 79.40% |

| West Europe | 15 | 7.90% |

| East Europe | 14 | 7.40% |

| Arab World | 10 | 5.30% |

| Total | 189 | 100.00% |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of dentists.

Of all responding dentists, 69% reported to have ever received a pregnant woman in their practice and the majority of responding dentists (86.5%) selected the second trimester as the period of choice to provide dental interventions for pregnant women (Table 2). Opinions regarding the risk of anesthesia and radiographs during pregnancy were contradictory. Around half of the sample (52%) considered anesthesia risky for pregnant women and only 55% would take a radiograph when necessary. Although 76% recognized gingival bleeding as a consequence of pregnancy, only 56% acknowledged gingivitis as a symptom (Table 2).

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Months of choice to treat a pregnant woman | ||

| 1st trimester | 12 | 6.50% |

| 2nd trimester | 160 | 86.50% |

| 3rd trimester | 13 | 7.00% |

| Total | 185 | 100.00% |

| Is anaesthesia risky for pregnant women? | ||

| Yes | 101 | 51.80% |

| No | 94 | 48.20% |

| Total | 195 | 100.00% |

| Do you do X-rays for pregnant women when necessary? | ||

| Yes | 105 | 55.00% |

| No | 86 | 45.00% |

| Total | 191 | 100.00% |

| Oral manifestations during pregnancy* | ||

| Caries risk | 59 | 30.10% |

| Gingival bleeding | 149 | 76.00% |

| Pregnancy gingivitis | 110 | 56.10% |

| Epulisgravidic | 41 | 20.90% |

| Dental fractures | 11 | 5.60% |

| Canker (Aphthous ulcers) | 18 | 9.20% |

| Dental sensitivity | 15 | 7.70% |

*Percentages in the manifestations during pregnancy may add to morethan 100 % because more than one option is allowed

Table 2: Knowledge and practice of dentists during pregnancy.

Prescription of medication

The vast majority of responding dentists would prescribe analgesics to a pregnancy woman (90.3%), the preference clearly being for acetaminophens (Paracetamol; 90.4%) (Table 3). Greater caution was apparent regarding the prescription of antibiotics (73.5%), but, when prescribed, the preferred antibiotic was a Betalactamin or Aminopenicillin (79%). The avoidance of anti-inflammatory drugs was clear, with only 9.2% willing to prescribe them during pregnancy (Table 3).

| Medications | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| GeneralFamilies | ||

| Antibiotics | 144 | 73.50% |

| Analgesics | 177 | 90.30% |

| Anti-Inflammatory | 18 | 9.20% |

| Antibiotics subtypes* | ||

| Betalactamine/Aminopenicilline (with or wihoutclavulonic acid) | 114 | 79.20% |

| Other Antibiotics | 17 | 11.80% |

| Based on gynecologist prescription | 21 | 14.60% |

| Analgesics subtypes* | ||

| Acetamenophene/Paracetamol | 160 | 90.40% |

| Based on gynecologist prescription | 6 | 3.40% |

*The percentage of subtypes in both antibiotics and analgesics refers only to the dentists who prescribe the medicine in each category

Table 3: Prescription of medicines.

Bivariate analysis

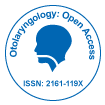

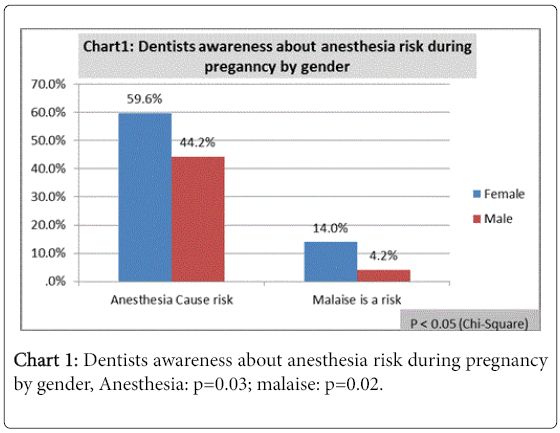

3When compared to male dentists, a higher proportion of female dentists reported that they would mention to a pregnant woman the risks of anesthesia (p=0.03), especially the risk of malaise (p=0.02; Chart 1). They were also more aware of the risk of gingival bleeding during pregnancy (p=0.05; Chart 2).

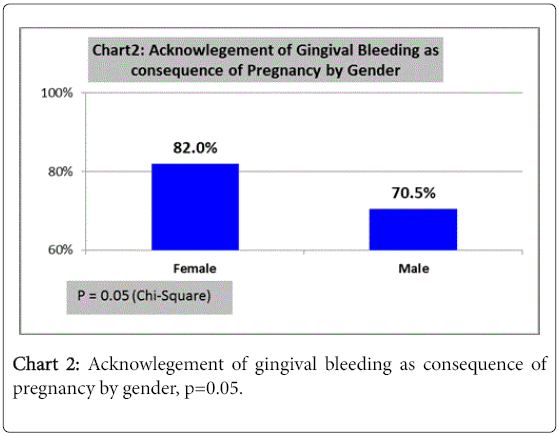

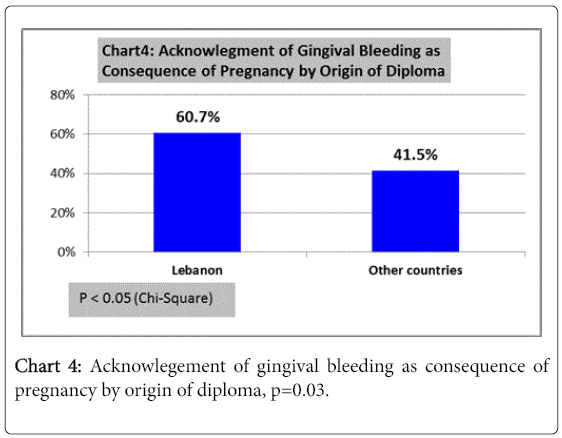

Experience was a significant predictor of the recognition of gingival bleeding as a consequence of pregnancy, dentists with greater years of experience being more likely of this recognition (p=0.04; Chart 3). With respect to the acknowledgement of gravidic gingivitis, dentists holding diplomas from Lebanese dental universities were more likely to recognize the association between with pregnancy than those holding degrees from other countries (p=0.03; Chart 4).

Discussion

The importance of maintaining good oral health during pregnancy is irrefutable. Early detection of oral pathology in pregnant women may contribute to the restriction of associated systemic diseases and thus the reduction of pregnancy and childbirth-related Complications [22,23]. Furthering the importance of maternal oral health care are the observations that preserving the expecting mother’s oral health during pregnancy may promote the establishment of a solid foundation for maintaining good oral health for her child after birth and may reduce the risk of early childhood caries [34-36]. The significance of maternal prenatal dental care is therefore increasingly being recognized, with recommendations for preventive, routine and emergency dental care in addition to pregnancy-specific counselling and oral health education [24,25,37]. Unfortunately, there is substantial evidence that as many as half of pregnant women around the world do not seek dental assistance during their gestational period, even when experiencing oral problems [12,25,34,38-41]. While numerous factors are implicated in reducing the utilization of dental health care by pregnant women, poorly informed or unprepared dental healthcare professionals often pose an additional barrier to the provision of dental health care services to pregnant women [33].

The results of our study suggest that both the beliefs and the practices of Lebanese dentists are suboptimal with respect to the oral health care of pregnant women. Despite gingivitis being the most common oral change during pregnancy [3], a quarter of the responding dentists did not consider gingival bleeding a consequence of pregnancy, slightly less than half acknowledged gravidic gingivitis and only about one fifth acknowledged pregnancy epulis. These proportions are strikingly low when compared to various international reports from different countries, where the proportions of dentists acknowledging the association between pregnancy and bleeding gums, gingivitis or periodontal pathology exceeds 90% [42,43]. It is interesting to note that female dentists were more likely to be aware of the risk of gingival bleeding during pregnancy and were also more likely to mention the risks of anesthesia, especially malaise, to pregnant women. A similar observation of greater knowledge among female dentists has previously been reported [44], although in another study no differences in the level of knowledge were observed between male and female dentists [24]. It is positive to note that with greater years of experience, dentists in our sample were more likely to acknowledge the association between gingival bleeding and pregnancy. Interestingly, dentists holding diplomas from Lebanese dental universities were more likely to recognize the association between gravidic gingivitis and pregnancy than those holding degrees from other countries. However, it is impossible to say whether this association is truly related to the country of education or is confounded by another factor, for example gender or years of experience.

Dentist practices regarding the use of local anesthesia and radiology were below recommended standards. Even though the use of local anesthetics with vasoconstrictors is considered safe throughout pregnancy [45], 51.8% of the responding Lebanese dentists believed that local anesthesia poses a risk during pregnancy and 61% believed the major risk from anesthesia is due to the presence of vasoconstrictors. The reluctance to administer anesthesia with or without vasoconstrictor observed in our sample supports the presence of similar misconceptions in several other countries. In another study in the region, 48% of dentists practicing in Saudi Arabia either considered epinephrine to be unsafe or were unsure about its safety [46]. Similarly, results from several studies of dentist practices across Europe and South America suggest that between 41 and 46% of dentists avoid the use of vasoconstrictors in pregnant women [45-49].

Despite the fact that diagnostic radiographs are believed to be safe during pregnancy when used with the recommended neck (thyroid) collar and abdomen shields, 45% of the responding dentists reported not to use radiographs even when needed [50]. A similar perception has been reported in Saudi Arabia, with 42.5% of dentists refusing to take a radiograph even when needed for diagnosis [46]. Data from international research is more heterogeneous, the proportions of dentists believing radiographs to be unsafe ranging between 18.4% [44] and 56.7% [51,52] in the USA and between 10.7% and 71.5% of dentists refusing to take x-rays during pregnancy in various countries [5,24,53,54].

With respect to the prescription of drugs, the practices of Lebanese conformed to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines. Almost three quarters of Lebanese dentists reported willingness to prescribe antibiotics, of whom around 80% would select Betalactamine/Aminopenicillin. These results fall in the range reported by regional and international studies where between 58 and 96 percent of dentists in various countries would prescribe penicillin or amoxicillin [5,46,49,53-56]. The vast majority of surveyed dentists would also prescribe an analgesic when needed and the first choice for more than 90% would be acetaminophen, with less than 10% willing to prescribe the less favourable option of NSAIDS [5]. Although most international studies report that more than 75% of dentists would prescribe acetaminophen or paracetamol [5,46,53-55], few studies report that about 50% of dentists would not [24,56]. The literature also confirms the reluctance of dentists towards the prescription of NSAIDs, with only 11-31 percent of dentists willing to prescribe aspirin, ibuprofen or NSAIDs in general [24,49,55,56]. Despite some limitations inherent to the study design and data collection method, the results of our study demonstrate that both the knowledge and the practices of Lebanese dentists with respect to pregnant women are lacking. It must be noted that the questionnaire used was not formally validated and was rather tested for face validity and ease of understanding in a focus group discussion followed by pilot testing in 15 individuals. Additionally, the nature of our convenience sample prevents the ability to generalize our results to include all practicing dentists in Lebanon. On the other hand, the high response rate and moderate sample size provide strength to our results and suggest that, although the exact percentages cannot be generalized to the entire population of Lebanese dentists, our study does capture a truly existing and previously unreported phenomenon of misinformation and incorrect practices among dentists in Lebanon with regards to pregnant women. Our findings demonstrate a need to broaden the knowledge of dentists in Lebanon regarding the care of pregnant women. This may require curriculum changes in undergraduate courses in Lebanon, but also practical training in order to empower graduating dentists and ensure the translation of knowledge into clinical practice. The high proportion of Lebanese dentists receiving degrees abroad may suggest the need to involve the Lebanese Dental Association in developing regulations that ensure that the knowledge of these dentists is either assessed or reinforced through training courses prior to enrollment in the association. The results also emphasize the importance of continuing education in the form of training courses and pregnancy-specific conferences, especially in the presence of a significant proportion of currently practicing dentists with incorrect beliefs and concepts. Additionally, in a culture where a physician’s opinion may sometimes be more valued by lay people than the opinion of a dentist, the importance of a multidisciplinary approach must be emphasized [38]. This requires the insurance that general physicians, gynecologists, obstetricians and midwives pose no barrier to the utilization of health care by pregnant women and that they become integral to the pathway of referral to dental care and counseling in early during pregnancy rather than a source of dissemination and strengthening of already existing misconceptions regarding dental care during pregnancy [38].

Conclusion

Our study illustrates clear deficiencies in the beliefs and the practices of Lebanese dentists with respect to the oral health care of pregnant women. While practices regarding the prescription of antibiotics, analgesics and NSAIDs conform to international guidelines, evidence-based knowledge regarding the association between pregnancy and gingivitis, in addition to the safe use of local anesthesia and radiology are all lacking. The data support the need for a comprehensive approach to strengthen the knowledge of all dentists practicing in Lebanon with respect to the oral health care and treatment of pregnant women.

This may necessitate a re-assessment of the dental curricula in local dental schools and/or the introduction of mandatory training courses into continuing dental education programs.

References

- World Health Organization (2005) The liverpool declaration: Promoting oral health in the 21st century. A call for action. Geneva: WHO.

- Azofeifa A, Yeung LF, Alverson CJ, Beltrán-Aguilar E (2014) Oral health conditions and dental visits among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004.Prev Chronic Dis 11: E163.

- Healther J, Boggess KA (2008) Periodontal diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A review of the evidence and implications for clinical practice. J Dent Hyg 82: 24.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2000) Oral health in America: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, (MD): U.S. Department of health and human services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health

- Naidu GM, Ram KC, Kopuri RK, Prasad SE, Prasad D, et al. (2013) Is dental treatment safe in pregnancy? A dentist’s opinion survey in South India. J Orofac Res 3:233-239.

- Turner M, Aziz SR (2002) Management of the pregnant oral and maxillofacial surgery patient.J Oral MaxillofacSurg 60: 1479-1488.

- Kloetzel MK, Huebner CE, Milgrom P (2011) Referrals for dental care during pregnancy.J Midwifery Womens Health 56: 110-117.

- Shamsi M, Hidarnia A, Niknami S, Rafiee M, Zareban I, et al. (2014) The effect of educational program on increasing oral health behavior among pregnant women: Applying health belief model. Health Education & Health Promotion 1:21-36.

- Silk H, Douglass AB, Douglass JM, Silk L (2008) Oral health during pregnancy.Am Fam Physician 77: 1139-1144.

- Barak S, Oettinger-Barak O, Oettinger M, Machtei EE, Peled M, et al. (2003) Common oral manifestations during pregnancy: Areview.ObstetGynecolSurv 58: 624-628.

- Steinberg BJ (1999) Women's oral health issues.J Dent Educ 63: 271-275.

- Gaffield ML, Gilbert BJ, Malvitz DM, Romaguera R (2001) Oral health during pregnancy: An analysis of information collected by the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system.J Am Dent Assoc 132: 1009-1016.

- Laine M (2002) Effect of pregnancy on periodontal and dental health.ActaOdontolScand 60: 257-264.

- RashidiMaybodi F, Haerian-Ardakani A, Vaziri F, Khabbazian A, Mohammadi-Asl S (2015) CPITN changes during pregnancy and maternal demographic factors 'impact on periodontal health. Iran J Reprod Med 13:107-112.

- Han YW (2011) Oral health and adverse pregnancy outcomes-what's next?J Dent Res 90: 289-293.

- Clothier B, Stringer M, Jeffcoat MK (2007) Periodontal disease and pregnancy outcomes: Exposure, risk and intervention.Best Pract Res ClinObstetGynaecol 21: 451-466.

- Xiong X, Buekens P, Fraser WD, Beck J, Offenbacher S (2006) Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review.BJOG 113: 135-143.

- Dasanayake AP1, Gennaro S, Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Chhun N (2008) Maternal periodontal disease, pregnancy, and neonatal outcomes.MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 33: 45-49.

- Vt H, T M, T S, Nisha V A, A A (2013) Dental considerations in pregnancy-a critical review on the oral care.J ClinDiagn Res 7: 948-953.

- Ruma M, Boggess K, Moss K, Jared H, Murtha A, et al. (2008) Maternal periodontal disease, systemic inflammation, and risk for preeclampsia.Am J ObstetGynecol 198: 389.

- Morgan MA, Crall J, Goldenberg RL, Schulkin J (2009) Oral health during pregnancy.J MaternFetal Neonatal Med 22: 733-739.

- Boggess KA, Edelstein BL (2006) Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: Implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health.Matern Child Health J 10: S169-174.

- López NJ, Smith PC, Gutierrez J (2002) Periodontal therapy may reduce the risk of preterm low birth weight in women with periodontal disease: A randomized controlled trial.J Periodontol 73: 911-924.

- Radha G, Sood P (2013) Oral care during pregnancy: Dentists knowledge, attitude and behaviour in treating pregnant patients at dental clinics of Bengaluru, India. Journal of Pierre Fauchard Academy (India Section) 27:135-141.

- George A, Shamim S, Johnson M, Dahlen H, Ajwani S, et al. (2012) How do dental and prenatal care practitioners perceive dental care during pregnancy? Current evidence and implications. Birth 39:238-247.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2011) Guideline on perinatal oral health care. Chicago, Illinois: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

- Kumar J, Samelson R(2006) Oral health care during pregnancy and early childhood: Practice guidelines. Albany.

- California Dental Association Foundation (2010) Oral health care during pregnancy and early childhood: Evidence-based guidelines for health professionals. J Calif Dent Assoc 28: 391-403.

- Achtari MD, Georgakopoulou EA, Afentoulide N (2012) Dental care throughout pregnancy: What a dentist must know.Oral Health Dent Manag 11: 169-176.

- The american academy of pediatrics and the american college of obstetricians andgynecologists (2007) Guidelines for Perinatal Care 6: 123-124.

- Lee RS, Milgrom P, Huebner CE, Conrad DA (2010) Dentists' perceptions of barriers to providing dental care to pregnant women.Womens Health Issues 20: 359-365.

- Pina PM, Douglas J (2011) Practice and opinions of connecticut general dentists regarding dental treatment during pregnancy. Gen Dent 2011;59:e25e31.

- Vieira DR, de Oliveira AE, Lopes FF, Lopes e Maia Mde F (2015) Dentists' knowledge of oral health during pregnancy: A review of the last 10 years' publications.Community Dent Health 32: 77-82.

- National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center (2008) Access to Oral Health Care During the Perinatal Period: A Policy Brief. Georgetown University.

- Gussy MG, Waters EG, Walsh O, Kilpatrick NM (2006) Early childhood caries: Current evidence for aetiology and prevention.J Paediatr Child Health 42: 37-43.

- Yost J, Li Y (2008) Promoting oral health from birth through childhood: Prevention of early childhood caries. Am J Matern Child Nurs 33: 17-23.

- Ojeda JC (2013) A literature review on social and economic factors related to access to dental care for pregnant women. The Journal 1:25.

- Alves RT, Ribeiro RA, Costa LR, Leles CR, FreireMdo C, et al. (2012) Oral care during pregnancy: Attitudes of Brazilian public health professionals.Int J Environ Res Public Health 9: 3454-3464.

- Hwang SS, Smith VC, McCormick MC, Barfield WD (2011) Racial/ethnic disparities in maternal oral health experiences in 10 states, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2004–2006. JMatern Child Health 15: 722-729.

- Thomas NJ, Middleton PF, Crowther CA (2008) Oral and dental health care practices in pregnant women in Australia: A postnatal survey.BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 8: 13.

- George A, Ajwani S, Bhole S (2010) Promoting perinatal oral health in South-Western Sydney: A collaborative approach. J Dent Res89:142301.

- Strafford KE, Shellhaas C, Hade EM (2008) Provider and patient perceptions about dental care during pregnancy.J MaternFetal Neonatal Med 21: 63-71.

- Tarannum F, Prasad S, Vivekananda L, Jayanthi D, Faizuddin M (2013) Awareness of the association between periodontal disease and pre-term births among general dentists, general medical practitioners and gynecologists. Indian journal of public health 57:92.

- Da Costa EP, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Zeldin L (2010) Dental care for pregnant women: an assessment of North Carolina general dentists.J Am Dent Assoc 141: 986-994.

- Zanata RL, Fernandes KB, Navarro PS (2008) Prenatal dental care: Evaluation of professional knowledge of obstetricians and dentists in the cities of Londrina/PR and Bauru/SP, Brazil, 2004.J Appl Oral Sci 16: 194-200.

- Al-Sadhan R, Al-Manee A (2008) Dentist’s opinion toward treatment of pregnant patients. Saudi Dent J 20:24-30.

- Pertl C, Heinemann A, Pertl B, Lorenzoni M, Pieber D, et al. (2000) Aspects particuliers du traitementdentaire chez la femme enceinte. Rev Men Suisse Odontostomatol42-46.

- Luc E, Coulibaly N, Demoersman J,Boutigny H, Soueidan A (2012) Dental care during pregnancy.SchweizMonatsschrZahnmed 122: 1047-1063.

- Navarro PSL, Dezan CC, Melo FJ, Alves-Souza RA, Sturion L, et al. (2008) Prescription medications and local anaesthesia for pregnant women:practices of dentists in Londrina, PR, Brazil]. Revista da Faculdade de Odontologia de Porto Alegre49: 22-27.

- The American academy of pediatrics and the american college of obstetricians and gynecologists (2011) Guidelines for Oral Health Care in Pregnancy.

- Da Costa EP, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Zeldin L (2010) Dental care for pregnant women: an assessment of North Carolina general dentists.J Am Dent Assoc 141: 986-994.

- Huebner CE, Milgrom P, Conrad D, Lee RS (2009) Providing dental care to pregnant patients: a survey of Oregon general dentists.J Am Dent Assoc 140: 211-222.

- Umoh AO, Azodo CC (2013) Nigerian dentists and oral health-care of pregnant women: Knowledge, attitude and belief. Sahel Med J 16:111.

- Caneppele TMF, Yamamoto EC, Souza AC, Valera MC, Araújo MAM (2011)Dentists’ knowledge of dentists of the care of special patients: Hypertension, diabetes and pregnant women. J Biodentistry Biomaterials 1: 31-41.

- Enabulele J, Ibhawoh L (2015) Knowledge of Nigerian dentists about drug safety and oral health practices during pregnancy. Indian J Oral Sci 6:55.

- Patil S, Thakur R, Madhu K, Paul ST, Gadicherla P (2013) Oral health coalition: Knowledge, attitude, practice behaviours among gynaecologists and dental practitioners. J Int Oral Health5: 8-15.

Citation: Lamia AAA, Daou DJ (2016) Pregnancy and Dental Treatment. Otolaryngol (Sunnyvale) 6:268. DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000268

Copyright: © 2016 Lamia AAA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 12636

- [From(publication date): 10-2016 - Apr 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 11573

- PDF downloads: 1063