Perspective Article Open Access

Places of Transit the Entries to Addis Ababa

Anteneh Tesfaye*

Delft University of Technology, Mekelweg 2, 2628 CD Delft, The Netherlands

- *Corresponding Author:

- Anteneh Tesfaye

Delft University of Technology, Mekelweg 2, 2628 CD Delft

The Netherlands

Tel: +31 15 278 9111

E-mail: A.T.Tola@tudelft.nl

Received Date: June 22, 2016; Accepted Date: July 08, 2016; Published Date: July 15, 2016

Citation: Tesfaye A (2016) Places of Transit the Entries to Addis Ababa. J Archit Eng Tech 5: 166. doi:10.4172/2168-9717.1000166

Copyright: © 2016 Tesfaye A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Architectural Engineering Technology

Abstract

Addis Ababa is functioning both as the political and commercial capital of Ethiopia and the seat for the African Union. This fact, together with its escalating leap in growth in reference to the rest of the cities in Ethiopia, led to an ever-growing amount of influx of people from all over the country to Addis Ababa. These people attracted by the "promising" city, migrate to Addis Ababa looking mainly for education and better job opportunities.

This phenomenon through the past decades has shown itself as one of the major causes for the formation of informal structures and systems within the city of Addis Ababa. The city of Addis Ababa has now places in its tissue named after smaller cities, towns and villages around the country. These parts of the city play the main role in the rural-urban flow by being temporary places for the people who come from the farthest areas of the country. They serve as entry nodes into the main system of the city.

Introduction

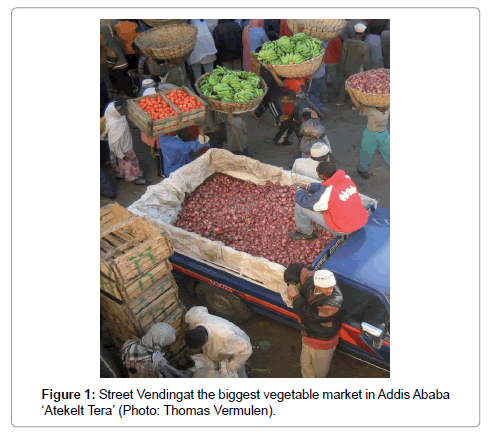

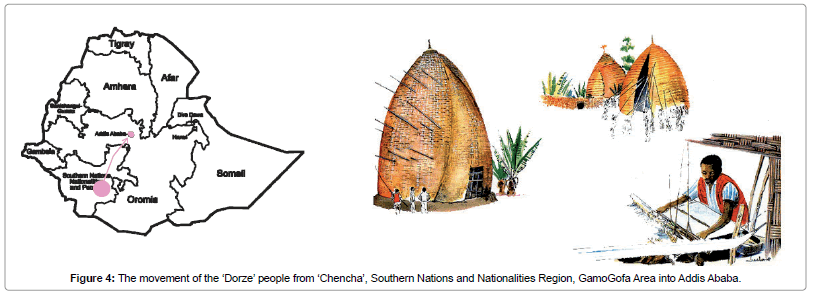

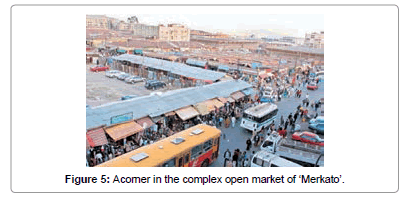

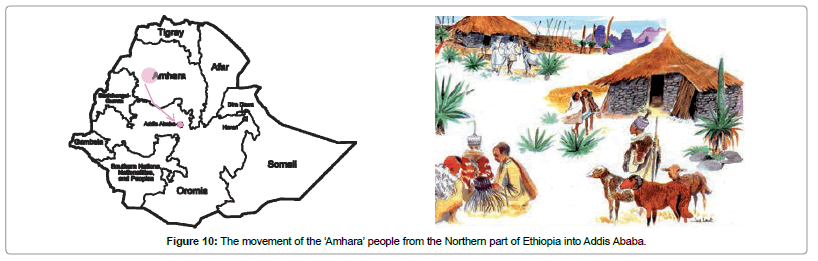

This article presents these areas in the city of Addis Ababa, which resulted from the overlapping of the urban system and the rural trend, and that are now informal "slums". This will lead to an understanding of how the two sides of the city are feeding each other. With this study, we take two sample areas ├ó┬?┬?Shiro Meda├ó┬?┬? and Merkato. ├ó┬?┬?Shiro Meda├ó┬?┬? is mainly inhabited by the ├ó┬?┬?Dorze├ó┬?┬? people, which migrated from the Southern part of Ethiopia. Merkato is the biggest open market in Africa from within which this paper takes only two case areas. The ├ó┬?┬?Kolkole Tera├ó┬?┬?, dominantly inhabited by the Guraghe People of Central Southern Ethiopia and ├ó┬?┬?Gojam Berenda├ó┬?┬?, whose main dwellers are the ├ó┬?┬?Amhara├ó┬?┬? people from the Northern Ethiopia (Figures 1 and 2).

The phenomenon of interdependence of the formal city and these islands of informality, which is evident mainly interms of activities and functions, can be enhanced by maximizing the surface of contact between them to create a sustainable and efficient urban system.

Background

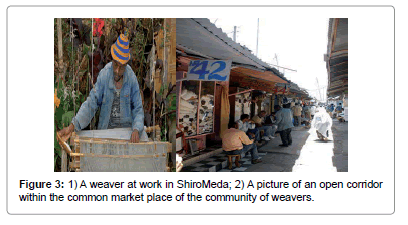

Informal Urbanism is usually understood as uncontrolled and constantly increasing density of living in a rather rapidly urbanized world which transforms depending on the needs of the collective and defying the over shading law and order of the place. This phenomenon was subject to marginalization and less attention was given to it until authors like Turner, Stokes and Mangin started studying and developing new urban theories that valued the process in which it was created (Figure 3).

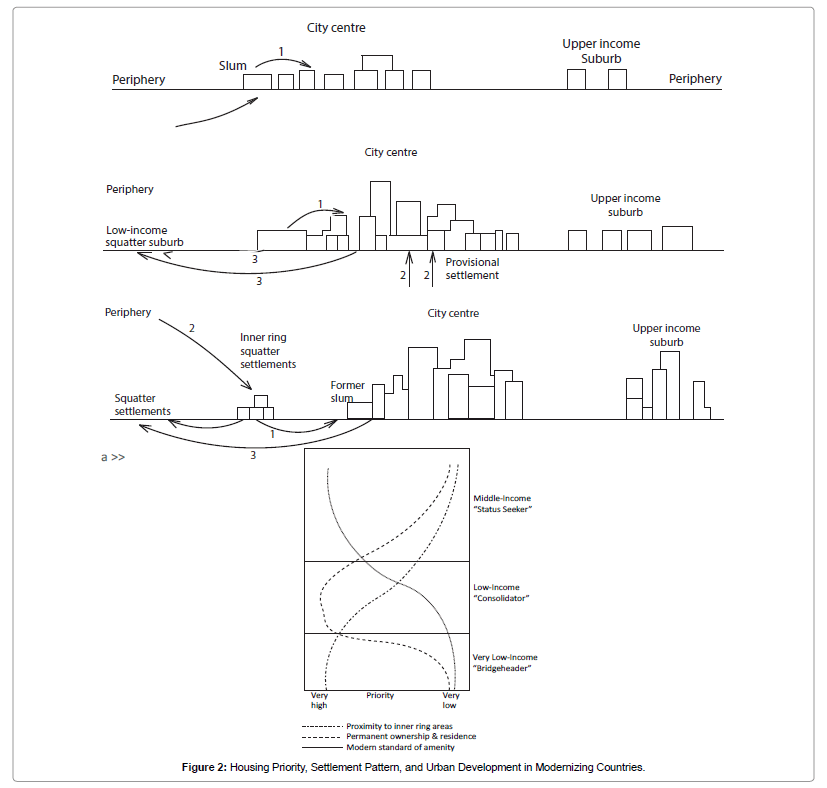

Different issues and facts can be pointed out as reasons for the creation of informal areas in big cities nowadays. But migration of people into urban areas stands out as the strongest and most historical factor. The temporal lifestyle that results from the movement of people into and within urban areas is one characteristic of informal settlements. In the diagram below, Turner formulates three housing priorities and shows how they sway through three categories of urban low-income migrants. From this diagram one can see that a new comer (usually from the category of very low income) gives high priority to proximity to the inner city to maximize opportunities and minimize commuting expenses, whereas ownership, permanence and quality of life are far coming priorities. This explains well the visual appearance of this informal settlements formed by the temporal and emergence needs of the collective [1].

Furthermore, Turner developed an ecological model shown in the diagram above that puts three clear phases to the development of such informal settlements in a city. Turner├ó┬?┬?s theory of intra-urban migration and the formation of informal areas took South American cities as a case. In different steps this theory seems to generalize and summarize the complex phenomenon and factors that result in these informal neighborhoods. In the priority theory he takes the optimist assumption that the urban immigrant passes through the three stages of social ladder, somehow neglecting the possibilities for either failure or change of direction. It also takes the mere assumption that, ├ó┬?┬?bridge headers├ó┬?┬Ł (as he calls the starters in the urban realm), tend to get to the city centre and through financial growth they tend to move into the outskirts, forming squatting satellites (Figures 4-6).

Taking this theory and testing the case in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, a city which somehow misses a clear centrality and instead emerged as a multi-central city, one can see that the ecological model of J. C. Turner needs a horizontal duplication factor of at least ten fold. This is the reason why Addis Ababa has quite a number of informal neighborhoods, which strongly display the transitional, temporality that Turner discusses in his theories [2].

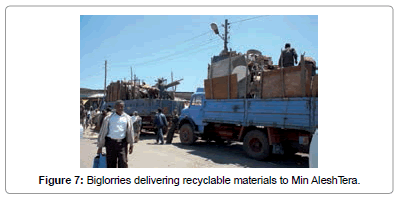

Migration

Ethiopia has primarily been an agriculture led economy for more than hundreds of years. Different regimes and governments have constantly worked to maintain this by keeping the working force in the rural places to their localities and maintain the labor balance accordingly. UNDP (2004) reported that about seventeen percent of the total population of Ethiopia lives in urban areas and this is expected to reach twenty-nine percent by the year 2020. Compared to most African countries, the urban population in Ethiopia is considerably small, but its growth rate is considered among the highest (about 3 percent). This figure did not take the late development plan [3] into consideration, which intends to strengthen the rural-urban linkage and focuses on the development of small towns and growth poles. Thus, migration is the most responsible factor for the growth of urban population (Figure 7).

The rural areas of Ethiopia are generally characterized by agriculture and craftsmanship. Non-sophisticated and traditionalvernacular systems are functioning as means of livelihood, whereas urban areas are experiencing an extremely fast transformation. This polarity, through time, has created curiosity and interest on the rural population into moving to these urban areas (Figure 8).

A research report by ESRC WeD [3] says the main reasons for the majority of urban migrations are lack of sufficient food, shortage of rural farmland, landlessness, and imposition of heavy land tax and the inability of farmers to pay their agricultural debts. The pull factors for the influx to the cities are mainly job opportunity and education. Employment opportunities such as daily laboring, loading and unloading of goods, street vending, shoe shining, urban farming, weaving, blacksmith, lottery ticket selling and begging are typical examples. Unmarried women are reported to engage in domestic work as housemaids, waitresses and commercial sex workers in bars; and in informal sector as petty traders [4].

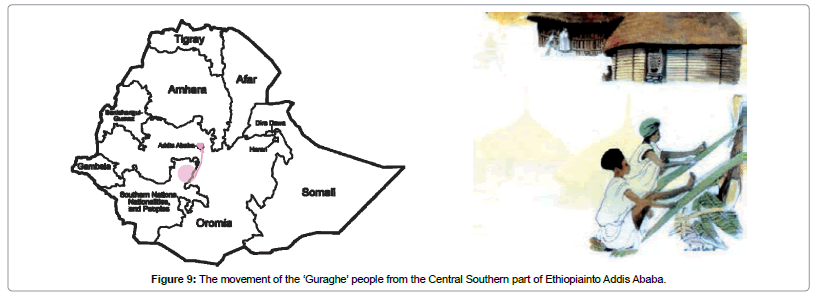

The other interesting characteristic of urban informal and transitory places is the specialization of each one towards a single kind of life style. This happens with the type of migration, which is based on ethnic groups and related people of similar places of origin. ├ó┬?┬?Ruralto- Urban migration in Sub-Saharan Africa, however, is not an aimless and spontaneous process: people who migrate to the city generally have well defined plans, contacts and destinations. Migration is structured by the extended family. Migrants who have more urban experience and who are well integrated in the urban economy give support to the new comers. They provide initial free accommodation and use their contacts and relations to find more stable accommodations and jobs for their ├ó┬?┬?bridge holder├ó┬?┬? relatives. Migrants from the same local or regional background often tend to cluster spatially. ├ó┬?┬?The clusters formed contribute a specific character both as social entities and economic inputs in the whole city scene (Figures 9-11).

This paper takes three cases from the city of Addis Ababa and discusses the phenomenon of urban transitional places as informal settlements. It analyses the relevance of these places of transit to the city and concludes with possible projections as to what the relationship between the two could be.

├ó┬?┬?Shiro Meda├ó┬?┬?: The Community of Weavers

This neighborhood was founded on the lower part of ├ó┬?┬?Entoto├ó┬?┬? mountain during the reign of Emperor Menelik II (1887-1941), by servants and workers of the royal palace located at the top of the mountain. Today, this area is dominantly inhabited by the ├ó┬?┬?Dorze├ó┬?┬? people migrating into the city from ├ó┬?┬?Chencha├ó┬?┬?, Gamo Gofa area in the region of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP). The ├ó┬?┬?Dorze├ó┬?┬? people are known for their craft skills, especially weaving. Their rural social system is known for its elaborate cooperative system.

Having these two main characteristics as rural cultural background, the ├ó┬?┬?Dorze├ó┬?┬? people have plugged and molded themselves into the city fabric of Addis Ababa. Right now the informal settlers of ├ó┬?┬?Shro Meda├ó┬?┬?, whose population size can be estimated in thousands, are the sole suppliers of authentic traditional garment to the city markets. This production and commerce, which was at the beginning their means for survival is now becoming a big cooperative franchise. Thus, letting the community stabilize itself in the formal economy of the city. Starting from the workshops at the household level, up to the communal traditional cloths markets of the neighborhood, there are now strong and visible urban and architectural spaces in these settlements (Figure 12).

MerkatoMerkato

Founded in 1936-37, during the time of the Italian occupation of Addis Ababa, Merkato is now the biggest open market in Africa. From this big and complex production and marketing hub this paper takes two sectors where these informal temporal places are witnessed.

Minalesh TERA├ó┬?┬?: recycling

This section of Merkato is predominantly inhabited by the ├ó┬?┬?Guraghe├ó┬?┬?people from the Central Southern part of Ethiopia. Similar to the ├ó┬?┬?Dorze├ó┬?┬? people, the ├ó┬?┬?Guraghes├ó┬?┬? also have a strong ethnic support system for migration into Addis Ababa. The ├ó┬?┬?Guraghe├ó┬?┬? are known for their skills and hardworking culture. They have a strong custom of technical production and entrepreneurship.

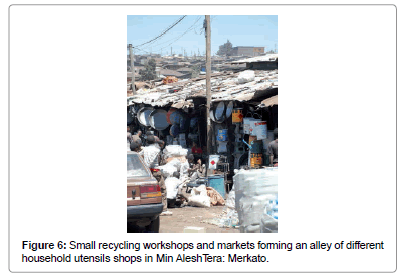

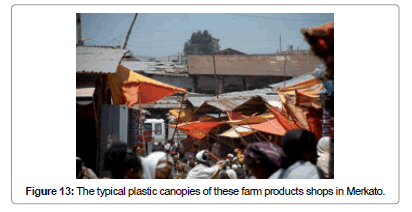

├ó┬?┬?Minalesh TERA├ó┬?┬?: recycling

This section of Merkato is predominantly inhabited by the ├ó┬?┬?Guraghe├ó┬?┬? people from the Central Southern part of Ethiopia. Similar to the ├ó┬?┬?Dorze├ó┬?┬? people, the ├ó┬?┬?Guraghes├ó┬?┬? also have a strong ethnic support system for migration into Addis Ababa. The ├ó┬?┬?Guraghe├ó┬?┬? are known for their skills and hardworking culture. They have a strong custom of technical production and entrepreneurship (Figure 13).

With their technical and business skills, the ├ó┬?┬?Guraghes├ó┬?┬? contribute to Addis Ababa in a rather tremendous manner. In ├ó┬?┬?Minalesh Tera├ó┬?┬?, almost every kind of waste the city of Addis Ababa is producing is reproduced into either similar or completely different materials. Steel materials are recycled into household stoves, sieves, troughs, dishes, trays and so on: car tires are either maintained for the same purpose or become shoes, chords, rubber ropes and the like.

As a result of the integration of these production spaces with housing and commerce this neighborhood has attained a very amorphous urban and architectural form. All spaces and building elements serve more than one function.

ATIKILT TERA├ó┬?┬?and ├ó┬?┬?Gojam Berenda├ó┬?┬?: urban agricul ture

In this section of Merkato, the predominant inhabitants are the ├ó┬?┬?Amhara├ó┬?┬? People from the Northern part of Ethiopia. This area is where most of the Ethiopian fertile highlands exist, thus the main source of livelihood is Agriculture. Either through strong professional chains connecting the rural farms to the city of Addis Ababa or by acquiring small agricultural plots within the city for farming, the ├ó┬?┬?Amhara├ó┬?┬? people are the main suppliers of agricultural products for Addis Ababa. Poultry, sheep herding, vegetable farming, spice and cereal farming are the main agricultural productions that this community is engaged in. These activities have led to the maximized use of outdoor spaces for production and commerce.

Perceptive Summary

├ó┬?┬?Places of Transit├ó┬?┬Ł are parts of the urban fabric where people emigrating from rural areas in to the city live temporarily. In addition to temporality these places show three main behaviors.

1. Invention born out of frustration: In these places, ruralvernacular life style confronts with the fast and competitive urban life style. The generous use of space, which is a character of rural areas, is challenged by the crowded and greedy urban space use. Due to this confrontations, most new comers experience beginners├ó┬?┬?shock. This in certain cases results in inventions that are born out of frustration.

2. Cooperative Systems: The extended family support system helps in dealing with the shocking confrontations. Even if the whole process of formation of these informal urban spaces is complex, the cooperative system that results from the ethnic similarity and practice, keeps it running rather smoothly (Figure 14).

3. Consistent Functional Performance: In all the three cases one can see that even if the members of the community keep changing due to reasons related with change of economic status these places of transit keep offering the same function to the whole city for a long duration of time.

Design Implications

It goes without saying that these ├ó┬?┬?Places of transit├ó┬?┬? play an undeniably strong role in the whole urban setup of Addis Ababa. However, physically segregated the formal and informal parts of the city might look, the functional interdependence is strong. The existence of these places has added a significant value of diversification, thereby reducing livelihood risks and vulnerability of the migrants in the city. Urban planning should therefore be directed towards maximizing the surface of contact between the formal parts of the city and these ├ó┬?┬?Places of Transit├ó┬?┬?. Urban design should create transitional or interactive spaces that which can accommodate the derived programs, which are neither urban nor rural, per say. Architecture should come up with new or grafted typologies, both specific and adaptable at the same time.

References

- Turner JC (1968) Housing Priority, Settlement Pattern, and Urban Development in Modernizing Countries. Journal of American Instituteof Planners, p: 358.

- Tadele F, Pankhurst A, Bevan P, Lavers T (2006).Migration and Rural-Urban Linkage in Ethiopia: Case Studies of five rural and two urban sites in Addis Ababa, Amhara, Oromia and SNNP Regions and Implication for Policy and Development Practice, prepared for Irish Aid-Ethiopia, FinalReport,Research Group on well being in Developing Countries Ethiopia Program, ESRSWeD Research Program University of Bath, United Kingdom, June 2006.

- Accelerated and Sustainable Development to End Poverty (2005) PASDEP, FDRE.

- Research Program, University of Bath, United Kingdom, June 2006 with the title Migration and Rural-Urban Linkages in Ethiopia.

Relevant Topics

- Architect

- Architectural Drawing

- Architectural Engineering

- Building design

- Building Information Modeling (BIM)

- Concrete

- Construction

- Construction Engineering

- Construction Estimating Software

- Engineering Drawing

- Fabric Formwork

- Interior Design

- Interior Designing

- Landscape Architecture

- Smart Buildings

- Sociology of Architecture

- Structural Analysis

- Sustainable Design

- Urban Design

- Urban Planner

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11296

- [From(publication date):

September-2016 - Apr 20, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10417

- PDF downloads : 879