Research Article Open Access

Placenta Processing: Sociocultural Considerations and Impact on the Future of Child in Benin

Fiossi-Kpadonou É1,4, Kpadonou GT2-4*, Azon-Kouanou A3,4 and Aflya MG5

1Department of Psychiatry of National Teaching Hospital (CNHU) of Cotonou, Benin

2Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine of National Teaching Hospital (CNHU) of Cotonou, Benin

3Department of Internal Medicine of National Teaching Hospital (CNHU) of Cotonou, Benin

4Faculty of Health Sciences of Cotonou, Abomey Calavi University, Benin

5Liberal Psychologist Cotonou, Benin

- *Corresponding Author:

- Toussaint G Kpadonou

Department of Physical and Rehabilitation

Medicine of National Teaching Hospital

(CNHU) of Cotonou, Benin

Tel : 00229 97588926

E-mail: kpadonou_toussaint @yahoo.fr

Received Date: March 26, 2015; Accepted Date: July 16, 2015; Published Date: July 21, 2015

Citation: Fiossi-Kpadonou É, Kpadonou GT, Azon-Kouanou A, Aflya MG (2015) Placenta Processing: Sociocultural Considerations and Impact on the Future of Child in Benin. J Child Adolesc Behav 3:222. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000222

Copyright: © 2015 Fiossi-Kpadonou É, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

Background: In Benin, placenta requires a heavily symbolic meaning. It is handed over to the family immediately after delivery and becomes an object of special care, even before the first body care to the newborn. Objective: To study the sociocultural considerations variants of placenta processing and their influence on the future of children in Benin. Methods: It was a prospective cross-sectional and descriptive study, referred on families of children aged 0-15 days. 180 questionnaires administered on a purposive sampling method, 150 were actually exploited. Results: For 84.7% of the families, placenta has been handled in the traditional ritual unchanged and in 15.3% of cases placenta manipulations different from sociocultural norms were observed. Placenta was buried in 81.3%, including 39.3% without accessories, and immersed in 07.3% of families. Conclusion: There is a strong link between the child and/or his family and placenta seen in the role of conservation, protection, requiring caution to the place of processing, eye and bad intentions. For centuries, and in almost all traditions, sociocultural considerations and care to placenta also maintain a certain psychological and social balance, hence its interest in psychotherapy. Will these sociocultural considerations of placenta and its strong link with the future of the child resist a long time to the changes of the society?

Keywords

Placenta; Ritua l; Processing; Sociocultural considerations;Child; Benin

Introduction

Benin is a country with multiple habits and customs, where current traditions, modern or modernized, are woven at the end of old ones [1]. This country has about sixty ethnic groups that can be clustered into five major cultural-ethnic categories; 93.4% of the populations practice a religion [2,3]. Religion and traditions guide and strongly influence the life in Benin, since birth or even before. Special consideration is given to the placenta according to magical-religious and sociocultural representations.

Qualified of double, accompanying each human being to life, of 3rd leg of the baby, t placenta is recovered by the family soon after the delivery and becomes subject to a specific attention, a ritualized care, a "treatment". During our various internships and practices in maternity wards, we observed that the placenta is delivered to the family for treatment even before the first body care to the newborn. How is the treatment of the placenta carried out? What are the different variations? Is there a meaning or specific consideration to each aspect of the treatment ritual of this biologic product? The aim of our study was to analyze socio cultural considerations variants of placenta processing and their potential impact on the child or his family in Benin.

Materials and Methods

It was a prospective cross-sectional and descriptive study, referred on families of children aged 0-15 days. The survey was conducted in Benin during three months, from 1 February to 1st May 2013. On the basis of a birth daily, or 30 per month, per departmental health block, it was considered for the six departmental blocks, an investigative population of 180 families of newborns aged 0 to 15 days. In each departmental unit were involved in the survey, new mothers whose output was decided following a good evolution of their own health state and the baby’s one. First mothers meeting these criteria were selected in the maternity department of each block according the importance of attendance maternities. At the end of the survey, 150 questionnaires were found to have been complete and usable on the 180.

Ethical provisions have taken into account the strict anonymity questionnaires sheets, the fathers’ agreement, consent and unconditioned new mothers’ membership, verbal permission and guidance of health facility managers to target mothers.

To gather the information, we used individual interview with the mother and the father or a family member present during the investigation. Interviews were conducted with 9 people 3rd and 4st ages, men and women, respondents having extensive knowledge of traditional practices.

The processing and the analysis of the data were performed with the Windows version of the software SPSS.

There is no conflict of interest concerning this article.

Results

Socio-demographic data

All ethnic groups in Benin were found among the families surveyed.

They were 48.3% boys and 51.3% of girls, with a sex ratio of 0.94. The average age of mothers was 25.8 years and 34 years for fathers. Place and Person in charge of welcoming the placenta. The survey found that the treatment of the placenta is very delicate and is made according to a whole ritual led almost entirely by the father and/or his family (98.7%), rarely by the mother or her family. We found some localities where the participation of the maternal family is culturally established, as it is the case with two families in wama ethnic group in the North Benin. The respondents unanimously revealed that access to the child's placenta is limited to privileged persons. Because any mishandling will be detrimental to the parents, to the mother, and particularly to the child.

Orthodox or modified traditional character of the ritual and knowledge of the ritual of the placenta.

The treatment of the placenta has been declared made according to the traditional ritual without modification in 84.7% of families (N=127), even if the details of the treatment were not given for 7.3% of the children (N=11).

An unusual change consisting in the use of Plastic bags for the placenta of 3 children Placenta was found in 2% of cases.

They did not answer to the question in 13.3% (N=20). Table 1 reports the details.

| Container | Accessories | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burial or Burying | Clay pot or Pot breakage | Without accessories | 59 | 39,3 |

| Leaves | 6 | 4,0 | ||

| Grains | 6 | 4,0 | ||

| Ashes to seal the pot | 3 | 2,0 | ||

| Palm oil with or without leaves | 3 | 2,0 | ||

| cowries with or without leaves | 2 | 1,3 | ||

| Cowries and traditional soap | 1 | 0,7 | ||

| Bean and banana | 1 | 0,7 | ||

| Monkey skin | 1 | 0,7 | ||

| Calabash | Calabash without accessory | 4 | 2,7 | |

| Leaf | Leaves without other accessories | 11 | 7,3 | |

| Plastic bag (nontraditional) | Plastic bag without accessories | 3 | 2,0 | |

| Without container | Without container and without accessories | 10 | 6,7 | |

| Cowries and loincloth worn by the mother during the birth | 1 | 0,7 | ||

| Details unknown | 11 | 7,3 | ||

| Immersion | Inside calabash | 8 | 5,3 | |

| No reply | 20 | 13,3 | ||

| Total | 150 | 100,0 |

Table 1: Various methods of placenta treatments observed.

Specific aspects of processing and sociocultural concepts and considerations

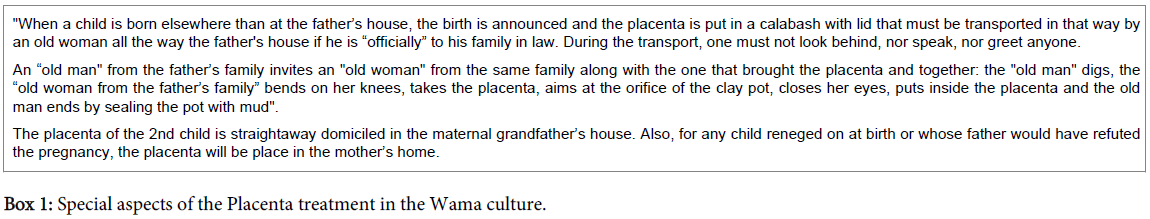

Details on the rituals and conceptions of the placenta in the wama culture are mentioned in Box 1.

"When a child is born elsewhere than at the father’s house, the birth is announced and the placenta is put in a calabash with lid that must be transported in that way by an old woman all the way the father's house if he is “officially” to his family in law. During the transport, one must not look behind, nor speak, nor greet anyone.

An “old man" from the father’s family invites an "old woman" from the same family along with the one that brought the placenta and together: the "old man" digs, the “old woman from the father’s family” bends on her knees, takes the placenta, aims at the orifice of the clay pot, closes her eyes, puts inside the placenta and the old man ends by sealing the pot with mud".

The placenta of the 2nd child is straightaway domiciled in the maternal grandfather’s house. Also, for any child reneged on at birth or whose father would have refuted the pregnancy, the placenta will be place in the mother’s home

The suitable place to host the placenta is the bathroom, which can be the mother’s bathroom or that of the family. Otherwise, the placenta is buried next to the hut, but essentially in the backyard, so that people can shower at the site of the burying for a while in order to give it some freshness. Bath time on the buried placenta varies. A common variant is 7 or 9 days depending on the sex of the child. The site of the burying should not be stepped on or otherwise desecrated by humans or animals; which is why it is buried in the bathroom or in a corner of the house.

In some areas of central Benin, the bedroom of the mother is now the preferred location; an altar is sometimes erected there (sometimes under the bed) for all the placentas of the same mother’s children, as an equivalent of a family vault, such that at the end of the mother’s reproduction cycle, when she becomes post-menopausal, a ritual can be carried out for the placentas of all her children

When a child has lost many older siblings, the Holli tie the placenta up after a whole set of ritual, mark the placenta and subsequently the child with distinctive signs of Abiku.

The placenta is coated with palm oil, and then buried in a clay pot, covered with leaves and cowries in a place where fire is regularly made. The nursing mother must shower at the site of the burying for 8 days.

While some key respondents declared that the placenta is buried in silence, some parents affirmed they pronounced prayers or wishes or "condensed" words (as incantations) during the ritual.

According to the explanations of the Wama grandmothers encountered during the survey: The calabash used to transport the placenta is filled with grain and sent (back) to the new mother. It will be used in the preparation of porridge for her. A consultation of the oracles is made before the delivery, allowing to know which ancestor is incarnated in the child. With this revelation, the "old man from the father’s family" who welcomed the placenta names the child. A chick is sacrificed on the representation of the tutelary ancestor and is subsequently hanged to the roof of the hut with a rod; a stone is sealed next to the ancestor who is now seconded.

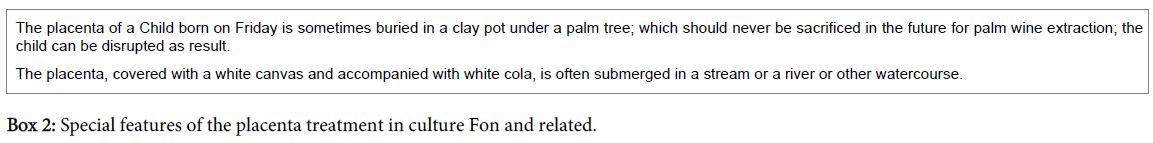

Some Fon people from Abomey and surroundings as well as some communities from the Mono-Couffo have a specific treatment for the placenta of the child born on Friday (Box 2).

In Ouémé/Plateau, in localities where live the Holli (ethnic group remained quite close to the nature), one massages the mother’s abdomen and lower abdomen while kneeling at the place where the placenta has just been buried.

Discussion

Sociocultural considerations and placenta manipulation

Delivery cannot be considered completed until the placenta has not been expulsed. One should wait for the complete expulsion of placenta before cutting the umbilical cord. It is only at that moment that the child can be raised. In many countries, matrons and midwifes still follow the traditions and hand the placenta over to the child’s family, sometimes even before installing the new mother [4-6]. In North Cameroon, results of a study reveal that cultural acceptability of biomedical services is impaired by a series of requirements such as a too early first prenatal visit; use in common of delivery rooms, wards and obstetrical tools; the absence of traditional healing like massage after delivery; refusal to hand over the placenta and umbilical cord to the family; and hindering the presence of family members during delivery. These evidences support a transition from normative medical system to an efficient and flexible medical system related to the expectations of the population established with its participation. This is commonly called patient-centred care [7].

Transport of the placenta from the Maternity at its final manipulation is secured by strict prohibitions preventing the wearer look back or talk, not even greeting. The tap of the primary living body of the child by the father or paternal family certify the recognition of paternity. In Goun ethnic group in south Benin, the umbilical cord is called “kukan” (line cord, cord or death). In Fon ethnic group (Center Benin), they talk about “nouzizan” that represent important things, having served previously in utero, and perhaps in another life to come? Death-life is an inseparable tandem for eternity. The child was born. The placenta that nourished in utero must disappear; although it will be then buried. This manipulation confirmed by culture is seen as a sign of good treatment and openness to life for the newborn. The placenta must not be buried in a din atmosphere, but almost in silence; it is not a popular jubilation, but a grave and serious ritual because the life of the child is thereby engaged.

Manipulation or care of the placenta is in almost all traditions. Beninese rituals overlap with others in Africa. The placenta is called in some Moroccan regions "Khout benadem" that is to say, the brothers of the newborn or "thimarten" meaning the baby sister [8]. It is then carefully protected and preserved eye wizards/witches, "bad people" who could use it to harm the child or parental couple. Also, it should not be dug, carried away or eaten by a dog or a pig? If this happens, affix a bad spell on the child. The placenta is then buried in a secret location, to allow a peaceful development of the child. Desecration is detrimental to the future of the child, perhaps on his life.

The search for security measures explains the fact that the bedroom of the mother may be the preferred location in some areas of Benin Center. Sometimes an altar is erected, under the bed, for all the placentas of the children of the same mother, as an equivalent of family vault. At the end of reproduction of the mother, when she will be menopausal, is performed a ritual for the placentas of all the children. And all children are reviewed and supposed to enjoy good and even protection.

We can understand why the placenta is often buried in the shower: the child whose placenta is refreshed daily, will receive much freshness in his life, even many blessings. The shower is the place reserved for family members and limited to a few people close to the parents it is "the back of the box," which anybody can not access. It is often a protected place from prying eyes.

By committing to wash the landfill by the fire of the child's placenta born after several infant deaths, the mother put the fire burning for some time (repeated death of children), to save the life to her newborn.

The placenta should be protected from evil eye or bad people because reaching the placenta and reach the baby is like. This is why some communities pack the placenta into the skin of the chimpanzee. The latter is a protective shield that the wizard symbolically meet in the place of the child. Thus, the child would remain protected despite a possible attack sorcerer or witch.

In place of relative silence that accompanies the ritual of placenta handling, they prefer to use some words "condensed" and strong, marked incantatory words to invoke God's blessing on the child.

In Benin, as in Morocco the subsequent reproduction depends on how the child's placenta is buried It is legitimate that the newborn has a sibling in which it will grow and make their experiences for better socialization. A major importance is placed on the person taking care of the treatment of this element; he must inspire confidence. Bettich [8] talks about the possibility available to the Moroccan mother who no longer wishes to have a child, to bury" the placenta with a big needle and salt". While this measure is deemed culturally reversible in Morocco because the mother can "re-open this secret space and recover the needle" for hope conceive again, in Benin, any "mishandling" during the treatment of the placenta is considered unrecoverable. A poorly buried placenta, whether intentionally or not, removes from the mother any chance of new conception and therefore reduces the father's offspring, hence one of the reasons of his full power on the treatment of hid children placenta.

In Benin, this role primarily falls to the father and the paternal family; the father's place is capital, "to every child a father is due" [9]. In cultures with a patrilineal system, the father (or his family) certifies his fatherhood from the moment he agrees to take the newborn’s placenta or delegates voluntarily and without coercion this power to someone else. Elsewhere, the father has the right to raise the baby, attested in the approval of the first bath to newborn; the enrollment in the paternal lineage is then established. The father has responsibilities, privileges, and rights over the child, to the child [10], that cultures in Benin confirm.

There is a ritual of the umbilical cord in some Arab cultures: it is knotted, "with nigella and cumin seeds in a piece of satin fabric. A specific day of the week, on early Thursday, the whole is put under the child's pillow ... for him to have affection for his father” wrote Ateya [11]. The same author reported that the dried cord is carefully preserved by the mother. Care descriptions made mention of a white cloth covering the placenta. Various grains (maize, millet, sorghum, cowpeas) accompany the placenta as a provision allowing it not to succumb from the 1st day of its journey through the cosmos. Coins or cowry shells (which have value of money in traditional societies), associated with the various elements would play the same role.

For now, the Beninese is still very attached to his child’s placenta. This element is considered as the child’s third leg or the child's double or "effects" that the father will be responsible for fixing, for rooting, quite often, in the paternal family home. Thus, from his first day, the newborn integrates his father’s home through his placenta, even before his release from the maternity ward.

We see that in many African countries, cultures work to treat the placenta to avoid any errors or mistakes, every curse, negligence or any sign of abandonment detrimental to the future of the child.

Specific features and other considerations in placenta processing

The Wama Culture has also thought of the mother for the domiciliation of the couple’s children placenta. That of the second child is assigned to the mother’s home. What fairness! It is like a (another) recognition of the mother and her family in the begetting work that could help prevent or clean up some frustration on the mother’s side. Co-parenting is thus attested and enjoyed on both sides in the entire lineage when the latter is not unique. Rooting a child’s placenta in a house gives him the right to call it home. He has the right and also the duty to come to that house, to stay or return without being worried.

Handling placenta allows the place of each family, both paternal and maternal, and requires both families collaboration around the placenta and around the child and his parents.

Massage practice of the abdomen and lower abdomen of the mother, kneeling at the place where the placenta has been buried, certify motherhood and helps the mother to take her maternality. The child is supposed to be better mothered.

The calabash used to transport the child’s placenta from the site of the birth to the father’s house returns to the new mother filled with grain. It symbolizes the acceptance of the baby and of his mother by the father’s family.

For a younger child who has lost many older a sibling, the Holli people from Benin attach the placenta up after a whole set of ritual; then distinctive signs of Abiku are marked on both the baby and the placenta. The placenta is coated with palm oil; it is subsequently buried in a clay pot and covered with leaves and cowries at a site where fire is regularly done.

Having the placenta close to the fire offers a deep meaning: only he who does not make fire or who has never eaten or will never eat a food cooked with fire can kill this child.

Placenta from children born on Friday is deemed to have a "hot" temperament. Their placenta must be submerged in order to give them some freshness.

Sometimes the placenta is buried by a woman (post-menopausal, born from the clan entitled to the placenta, or spouse of one of its members) and a man of the clan. The latter digs the hole, the first puts inside the placenta and the man completes the burial. It's like a beautiful work of procreation, of co-procreation that represents the support to the biological parents and the child from an older symbolic couple, as a prevention of conflicts within the conjugal couple of the parents, or difficulties in the life of this child.

Socio-cultural representations of the various elements

The palm tree or other tree planted at the placenta burying site must be maintained. That becomes a requirement for the parents and later for the child himself, since it is believed that the health of the child depends on the good growth of the tree. If it is a palm tree, it must not be sacrificed for palm wine production; this would be very detrimental to the child. One can perceived there a strategy to protect the palm tree, a tree that generates a long term income through many of its products and therefore should not know a vile end.

The young fruit or palm tree planted at the site of the burying, and sometimes (also) grains buried free with the placenta are intended to grow. They represent vegetal element of life. In a first phase, nutrients from the placenta and care including watering by parents and children will help them grow. In a Second phase, the trees (or grains) will bring benefits through their fruits, but they essentially symbolize life and hope.

Traditional thinkers have certainly observed that the texture of the placenta is very reminiscent like a tree.

The leaves used in the ritual bear a specific name: "leaves of the blood" (Hounman in fon language of Benin). A newborn is considered to have just come out of blood. One can therefore refer to these leaves at this moment. It is possible to be in presence of leaves named secondarily, after they have started being used.

The massage of the abdomen and lower abdomen at the site of the burying seems to be a sign to make symbolically acceptable the separation of the placenta carried so long in that womb by that mother at the same time as the fetus.

The placenta seals a link between the living and the ancestors: the elderly ("old man") of the paternal family that welcomed the placenta provides the name. A chick is sacrificed on the representation of the incarnated ancestor, and then hung to the roof of the hut with a rod. A stone is sealed next to the ancestor. Thus this ancestor is now seconded. It is supposed to better care for the baby, protecting against all evil and better accompany his destiny.

The burial of the placenta in Benin requires the same consideration as that of a human being. It is accompanied with food and money (coins and cowries), traditional soap and palm oil. It is given freshness, protection and marker. It is buried with a linen (leaves...) after washing it as a dead human being ... It is sometimes well washed before being burying, sometimes knotted in a canvas, often white.

The clay pot, the calabash, would constitute a kind of coffin. Its grave is marked by a stone, a specific fruit tree, and an altar with a thanksgiving ritual the following days.

There is a strong link between the child and the placenta perceived, among others, in the role of conservation, protection, requiring caution, in relation to the site of treatment, to bad eyes and bad intentions. A confusion child-placenta sometimes occurs. One can then understand the marking of both when the child is in a situation of abiku; this situation of multiple losses of children in the family, imposes other strong rituals such as the covering with a piece of chimpanzee skin, the burying at a site where fire is made. Indeed, by covering the placenta with the solid skin of a strong enough animal, the child will become protected, well protected.

The addition of cowries in the container (the coffin, the casket) of the placenta suggests the assurance of a life without lack, because the cowrie symbolizes money, wealth. At the end of life on earth, fon people, goun people and other ethnical group in Benin also cover the body with a specific shroud and, among others, place coins in the coffin so that the dead does not lack anything during his trip, before he meets and is welcomed by his ancestors. The analogy is quite striking.

Still on the preservation, the fear of cannibalistic wizards is more and more forcing to a change in the selection of the burying site of the placenta, the bedroom of the mother, for example. Just like the condensed remains of a deceased contained in its appendages, the placenta is buried at a hidden site, not accessible to everyone.

The burial of the placenta is thought to restore or maintain the fertility of women both in number and European African countries (Benin, Ghana, Sweden in the 19th century in pagan called then) [4]. One perceives and that there is considerable link between the placenta and the future siblings (brothers and sisters).

Precautions in relation to the mother who must not see the placenta if she wants to have more children;

Precaution in relation to the position of the fetal umbilical cord: it must remain towards the top for the proper order of events to come;

Precaution in relation to the person in charge of burying the placenta: it must be an authorized person, a well-minded person; he may otherwise become a risk for both the child and the siblings to be born.

The placenta of the child who was born alive but died subsequently and that of the stillborn are psychologically difficult to manage, for the main component no longer exists and one must dwell on the accessory. We may think that there is no longer any direct benefits associated with it, but it still needs to be processed in order to give the mourning mother a chance to have another child.

At the end of his life on earth, the human being will be buried as was his placenta. Ancestor might have thought that the dead is going to meet his placenta to (re)do the road him, which could partially justify the persistence with which we wish sometime that the deceased be buried in the same land as his placenta. The Beninese is often strongly attached to that place throughout his existence, as long as he does not encounter any major obstacle.

Thus, positive relationships between the placenta and the child are well known and raised. However, there are also negative or even harmful aspects and role of the placenta that need to be stressed.

Negative aspects, recent scientific considerations and cultural analogies

When parents own their homes, they do not face free decision issues; but it is becoming more and more difficult for tenants to obtain their landlord’s agreement in order to bury the placenta where they live. Some Fathers have been forced to go back to their native village for the treatment of their newborn’s placenta, even before inquiring about the first needs of the new mother, whether she was assisted or not. Resentments and frustrations may therefore appear from the problematic of the placenta, not to mention the predestination that the child to that organ.

Several authors have built bridges between cultural and symbolic representations of the placenta with scientific and/or modern consideration [11]. Studies have recently shown in the United States that sudden death may be associated with a thin placenta (study conducted on a cohort of 13,345 men and women, with p = 0.006) [12]. Some particular placental phenotypes could predict certain diseases in adulthood (heart disease, metabolic and even psychiatric diseases) [13]. It is estimated that more growth is a process that begins from life in utero and certified by placental weight and anthropometric values of the baby and the mother [14].

They need additional researches on the links between the processes of placentation and the morphology of the placenta at birth in order to better to decide.

Therefore, the association of the child's fate to that of the placenta that nourished in the uterus does not seem illogical; from both a beneficial and an evil stand point.

Ecological vision of the placenta processing

An ecologic look allows us to notice that the treatment of the placenta introduces a number of solid materials, not always of rapid degradation, in the bathroom and other places invested by the ritual, in homes or waterways.

And what if animals (mammals and herbivores) had the best formula (at least more ecological) consisting in eating the placenta used to feed their child in the uterus, without mentioning its symbolic and/or fantastical link of attachment?

Humans found in turn the placentophagy [15]; thus, in some cultures, the placenta is cooked and eaten as a family, to celebrate the birth and strengthen family ties. Indeed, if the word placenta originally means cake or wafer in Latin [16], one can understand that the organ so called is connected to ingestion fantasies. Some authors have spoken about its energizing and de-stressing properties [17].

The placenta-art has been around for a while, allowing to artistically materializing the organ of the mother-child initial link. This permits a long term preservation of the placenta without any more the need to keep other link through a ritual and the use of a number of elements that are not easily degradable.

The placenta contains rich nutrients, whose virtues were exploited in the cosmetics industry. Some cultures have finally abandoned the ritual, now using technologies for a "more hygienic reduction" of what was once very valuable to the family. With the advent of AIDS, the placenta is nowadays treated as a (suspect) waste in industrialized countries; it is therefore neutralized and burnt.

Time, degree of development and level of science play their partition. What is or will be at stake?

Conclusion

The placenta requires a heavily symbolic meaning at several levels, for centuries and in many cultures. It is present early in the life of the human being, to whom it allows a development in the Uterus. It permeates the life of the human being from beginning to end, actually and symbolically. The placenta is treated with considerations based on observation, experience, sense, resentments and expectations of humans, which affixes a certain mental balance, hence its interest in psychotherapy.

Will these sociocultural considerations of the placenta and the strong commitment of the future of the child assigned to it resist a long time to the changes experienced by our societies? Subsequent studies will provide answers in the coming years.

References

- FiossiKpadonou E (2003) The new rope braid after the former or the role of paternal transmission in the mental well-being in adolescence in Benin? In Enfances Adolescences, SBPDAEA 5: 55-65.

- (2002) Insae rgph-3 third general census of population and housing.

- (2013) Insae rgph-4 fourth general census of population and housing.

- Hallgren R (1983) West African childbirth traditions. Jordemodern 96: 311-316.

- O'Driscoll T, Payne L, Kelly L, Cromarty H, St Pierre-Hansen N, et al. (2011) Traditional First Nations birthing practices: interviews with elders in Northwestern Ontario. J ObstetGynaecol Can 33: 24-29.

- Pizzi M, Fassan M, Cimino M, Zanardo V, Chiarelli S (2012) Realdo Colombo's "De Re Anatomica": the renaissance origin of the term "placenta" and its historical background. Placenta 33: 655-657.

- Beninguisse G, De Brouwere V (2004) Tradition and modernity in Cameroon: the confrontation between social demand and biomedical logics of health services. Afr J Reprod Health 8: 152-175.

- Bettich IM (1995) Cultural representations of perinatal care in Morocco in the notebooks of Afree, Montpellier 9 Cultural Identity and Birth 102-120.

- Naouri A (1985) A place for the father Threshold Parispp: 9-12.

- JulienPh (1991) The mantle of Noah DescléeBrouwer Parispp: 73-77

- Ateya M (1995) Kids and parents from here and elsewhere in the notebooks of Afree, Montpellier, 9 Cultural Identity and Naissance pp: 81-83.

- Barker DJ, Larsen G, Osmond C, Thornburg KL, Kajantie E, et al. (2012) The placental origins of sudden cardiac death. Int J Epidemiol 41: 1394-1399.

- Barker DJ, Thornburg KL (2013) Placental programming of chronic diseases, cancer and lifespan: a review. Placenta 34: 841-845.

- Soliman AT, Eldabbagh M, Saleem W, Zahredin K, Shatla E, et al. (2013) Placental weight: relation to maternal weight and growth parameters of full-term babies at birth and during childhood. J Trop Pediatr 59: 358-364.

- Cremers GE, Low KG (2014) Attitudes toward placentophagy: a brief report. Health Care Women Int 35: 113-119.

- Proust C (2012) Why women eat the placenta after childbirth.

- Edding C (2007) Placenta: The Gift of Life pp: 17-22.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16023

- [From(publication date):

August-2015 - Jul 06, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11399

- PDF downloads : 4624