Pharmacovigilance and Clinical Safety: Comparison between India, US and Europe-A Review

Received: 01-Apr-2023 / Manuscript No. ijrdpl-23-90309 / Editor assigned: 03-Apr-2023 / PreQC No. ijrdpl-23-90309 / Reviewed: 17-Apr-2023 / QC No. ijrdpl-23-90309 / Revised: 21-Apr-2023 / Manuscript No. ijrdpl-23-90309 / Accepted Date: 27-Apr-2023 / Published Date: 28-Apr-2023 QI No. / ijrdpl-23-90309

Abstract

Pharmacovigilance (PV) is a crucial component of the system for regulating pharmaceuticals. PV is essential for the detection, evaluation, and dissemination of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) using a variety of channels. ADRs cause significant harm to patients and can possibly increase morbidity and mortality. The public health safety and promotion of responsible drug use are both aided by the PV databases. In order to broaden the scope of the current PV structure in India, this essay analyzes the PV systems in the USA, Europe, and India while underlining the difficulties and potential solutions. In comparison to other nations, PV schemes in India are still in their infancy.

Keywords

Pharmacovigilance; PV; Clinical trials; Kidney failure

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines pharmacovigilance as "the science and actions relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drugrelated concern [1].

Need of pharmacovigilance

For a product to be successfully introduced to the market, clinical trial data should be able to potentially reflect the safety and effectiveness of a drug. Clinical trials are often conducted on a small, carefully selected sample, allowing only the detection of common side effects. However, the reaction that takes place in a certain person over an extended period of time goes unnoticed. This calls for the need of Pharmacovigilance [2].

a. AIMS

1. Early detection of unknown adverse drug reactions & interactions

2. Detection of an increase in the frequency of (known) adverse reaction

3. Identification of risk factors & possible mechanisms underlying adverse reaction

4. Estimation of benefit/risk analysis

5. Patient care & safety

6. Products considered under pharmacovigilance are herbal medicines, conventional medicines, vaccines, medical devices, blood products, biologicals & other traditional & complementary products.

Evolution of pharmacovigilance [3-5]

1747: James Ling presented a clinical research that demonstrated the value of lemon juice in scurvy prevention

1937: Sulphonamide catastrophe of 1937,Sulphonamide was dissolved in diethylene glycol, causing kidney failure in over 100 persons.

1938: The FDA mandated preclinical toxicology and pre-marketing clinical evaluations.

1950s: Aplastic anaemia was brought on by the use of chloramphenicol

1960: The FDA launched a programme for hospital-based medication monitoring.

1961: Thalidomide disaster.

1963: The 16th World Health Assembly emphasised the significance of taking swift action on ADR

1968:WHO launches the International Drug Monitoring Program

1970s: Clioquinol was discovered to be associated with Subacute Myelo Optic Neuropathy

1980s and 1990s: there were numerous medications that had severe side effects.

1996: India began conducting international clinical trials

1997: India joined ADR Monitoring Program.

1998: PV activity started in India

2002: Establishment of India's 67th National Pharmacovigilance Center.

2005: India began organizing clinical trials

2009-2010: India's PV strategy was launched and put into action.

Pharmacovigilance program in India

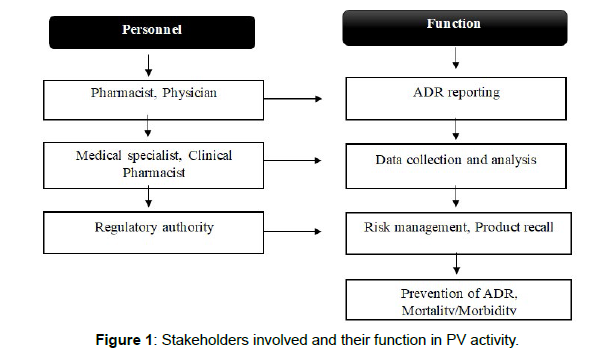

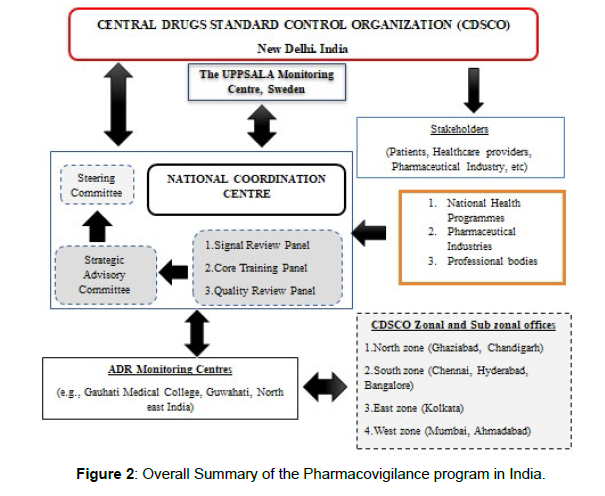

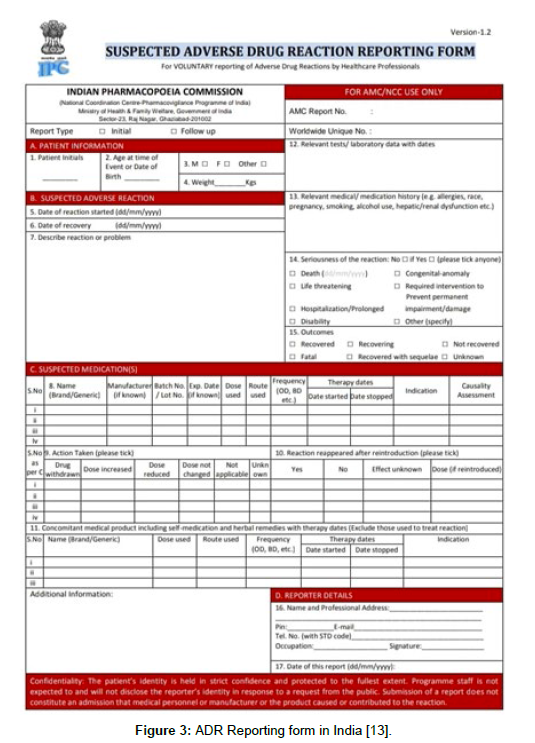

At Uppsala, Sweden, in 1997, India combined its PV system (Figure 1) with the WHO ADR Monitoring Program. Monitoring centres were subsequently set up, including 2 WHO special centres in Mumbai and 1 in New Delhi. These centres were unable to accomplish their goals due to a lack of financing and adequate counselling regarding the necessity of reporting ADRs [6]. The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization's National Pharmacovigilance Advisory Committee developed the National Pharmacovigilance (Figure 2) Program in January 2005. The Uppsala Monitoring Center and the committees of the South-West and North-East zonal centres were to receive evidence of incidents around the nation. The development of a national Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI), which was overseen by the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, in 2010 was prompted by the requirement for increased ADR (Figure 3) surveillance in India. The National Coordination Center (NCC) had been operating out of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi until it was later given to the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission (IPC), a self-governing organisation under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, as of April 15, 2011[7].

Figure 3: ADR Reporting form in India [13].

What to report? [8]

• Death or a life-threatening situation

• The patient's hospitalization

• Congenital defect

• Significant medical event (If the event is considered serious by the physician)

• A medicine or medical device's use is associated with a lack of efficacy.

• Every possible medication interaction

When to report?

• Within 10 days, all spontaneous cases must be recorded.

• All suspected ADRs should be reported as soon as feasible because it's always better to report more than you should.

• All major ADRs and events must be notified within 7 days of the event, with the exception of deaths, which must be reported as soon as feasible.

• Within 30 days, all minor instances must be reported.

Who can report?

The preferred source of information in PV is a healthcare team member, such as

• a medical specialist,

• a pharmacist,

• a dentist,

• Or a midwife.

• Patients, patients' loved ones, witnesses, or any regular person may report along with HCPs after receiving medical confirmation [9, 10].

How to report?

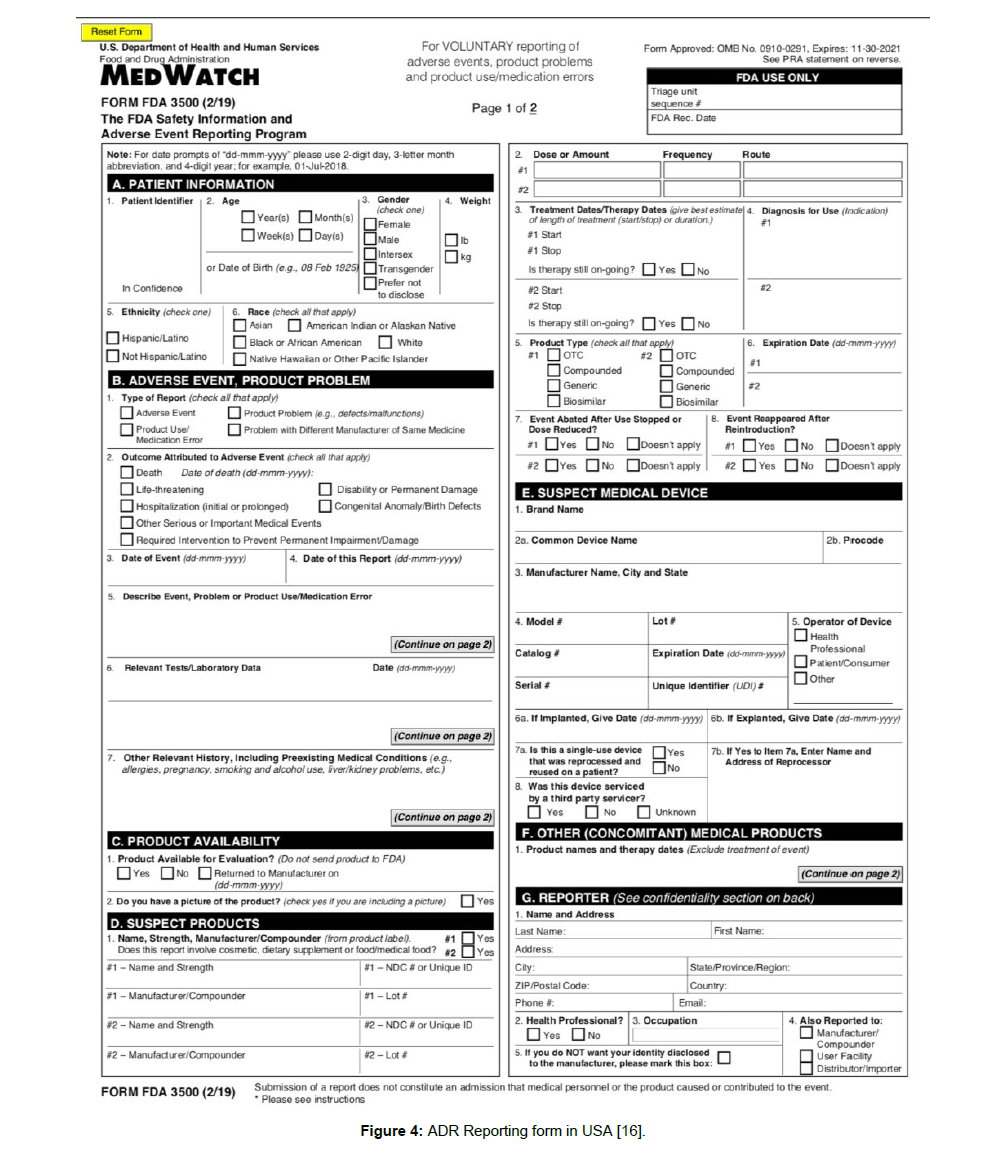

ADR reporting forms must be properly completed and sent to the NCC or the nearest AMC. To report ADRs, call the 1800 180 3024 tollfree helplines. Directly mailing the completed ADR reporting (Figure 4) form to pvpi@ipcindia or pvpi.ipcindia@gmail.com. Visiting the websites http://www.ipc.gov.in and http://www.ipc.gov.in/ PvPI/pv home.html to find a list of India's authorised AMCs [11].

Figure 4: ADR Reporting form in USA [16].

Where to report?

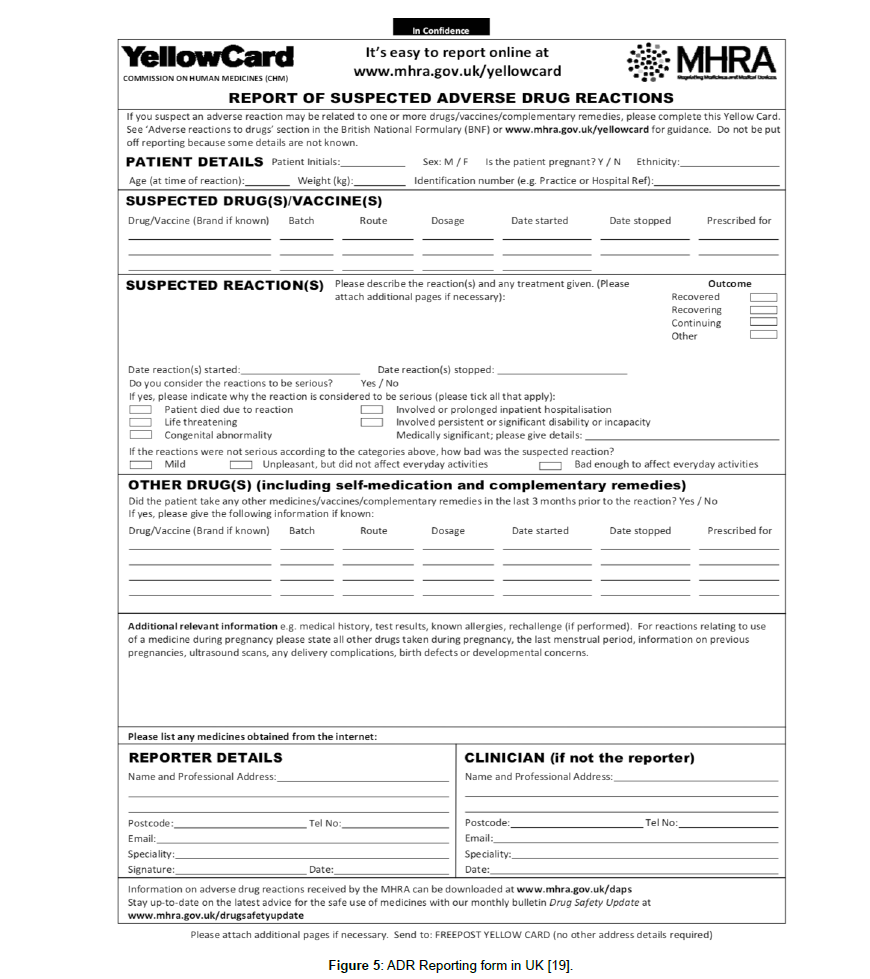

Peripheral PV centre: It serves as the main ADR information hub. Small medical facilities, independent medical centres, dispensaries, nursing homes, and pharmacies are all included. RPCs or ZPCs are in charge of identifying and synchronising ADRs. This peripheral centre is present in every state, every union territory, and some of India's top medical schools (Figure 5).

Figure 5: ADR Reporting form in UK [19].

Regional PV centre: It is considered a secondary PV Center. The greater. By means of zonal centres, they are located and managed. India has five of these regional hubs.

Zonal PV centres:It is thought of as a Tertiary PV Center. Usually found in a medical college in a major city with adequate attachments. It is recognised by CDSCO and serves as the first location for collecting ADR data. AIIMS serves as the zonal centre for the north and east [12].

Pharmacovigilance program in Us

To facilitate postmarket surveillance in the USA, (Table 1) the FDA created the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS; formerly known as Adverse Event Reporting System), which enables producers, medical management experts, and subjects to present adverse event reports. The database contains data on adverse events, medication errors, product quality concerns, and patient demographics [13,14].

| Parameters | India | USA | EU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory authority | CDSCO | FDA | EMA |

| Authority responsible for PV | National Coordination Centre-IPC | CDER or CBER | European Commission, EudraVigilance Data Analysis System (EVDAS) |

| Online ADR reporting | Vigiflow | MedWatch | EudraVigilance |

| ADR forms | One ADR form | 1. 3500A: Mandatory reporting for regulated industries and facility users 2. 3500B: Voluntary reporting for consumers and healthcare professionals |

Individual Case Safety Report (ICSR) form Three ICSR forms are available: Level 1, Level 2a, and Level 3. These three forms adhere to the same guidelines and have the same structure, but they differ in the ICH-E2B(R3) data items they use to satisfy the Eudra vigilance access policy. |

| Guidelines | PSUR, Schedule Y, Pharmacovigilance Guidance Document for MAHs of Pharmaceutical Products | Good PV Practices and Pharmacoepidemiologic Assessment | Good Pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) |

| PV database | Vigibase | FAERS Sentinel System |

European Database of Suspected Adverse Drug reactions Reports, EudraVigilance Data Analysis System (EVDAS), EudraVigilance WEB trader (EVWEB) |

| Periodic safety reports | Periodic Safety Update Report (PSUR) | Periodic adverse drug experience reports (PADERs) | Periodic Benefit Risk Evaluation Report (PBRER) |

| Spontaneous case reports (serious AEs) | Within 15 d | Within 15 d | Within 10 d |

| Risk management system | Pharmacovigilance guidance document for all MAHs of Pharmaceutical Products effective from 2018 | Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) | European Risk Management Strategy |

Table 1: Contrasts between Indian pharmacovigilance, the US, and Europe [25].

Patients and healthcare professionals can voluntarily report severe adverse events and other problems they believe are related to the use of an FDA-regulated product through the FDA's MedWatch web-based reporting system. Patients and healthcare professionals can voluntarily report severe adverse events and other problems they believe are related to the use of an FDA-regulated product through the FDA's MedWatch web-based reporting system. The FDA or the manufacturers can be informed in detail of the adverse events. Information on both required and optional reporting is available from MedWatch [14-16]. The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research or the Center for Biologics Evaluation reviews the ADR reports submitted online via 2 form 3500As or 3500Bs. Under the US FDA Amendments Act of 2007 for the mandatory submission of adverse events by the makers, the FDA launched the Sentinel Initiative [15].

Pharmacovigilance program in Uk

The EudraVigilance system compiles, manages, and analyses suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with medications licenced in the European Economic Area. The European Medical Agency was established in 1995 to assess pharmaceuticals [17]. Patients and healthcare professionals report suspected ADRs to EudraVigilance or MAHs. The Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee assesses all potential risks and oversees drug supervision. The aforementioned committee takes into account the conclusions, evaluation, reduction, and announcement regarding the risks of adverse responses while keeping the therapeutic benefit of the drug in mind [18]. In the UK, Pharmacovigilance continues to fall under the purview of the MHRA.

You, as a Marketing Authorization Holder (MAH), will be expected to report pharmacovigilance data to the MHRA in accordance with UK regulations for medicines that are authorised nationally in the UK, including:

• Reports on individual cases of safety in the UK and abroad (ICSRs)

• Reports on recurring safety updates (PSURs)

• Plans for managing risks (RMPs)

• Final research reports and Post-Authorisation Safety Studies (PASS) protocols

In order to best promote patient safety in the UK, they will be evaluated while taking into consideration all pertinent facts, and decisions will be made using UK clinical practice. Abbreviations: CBER, Centre for Biologics Evaluation; CDER, Centre for Drugs Evaluation and Research; CDSCO, Central Drugs Standard Control Organization; FAERS, FDA Adverse Event Reporting System; MAHs, Market Authorization Holders.

The challenges

The underreporting of ADRs is India's main PV problem. There are a number of reasons for this, including a lack of qualified medical personnel, insufficient national PV awareness, and inadequate available resources [20]. Only 250 of India's more than 450 medical schools and hospitals that have been authorised by the Medical Council of India are currently AMCs. Lack of a reliable system for reporting and analysing different ADRs, prescription errors, patient compliance, and drug interactions is another issue the PV system in India is dealing with. It would be sage to work with them and create a system rather than adopting a WHO-based ADR reporting system because India has a sophisticated IT sector [21]. The most recent PvPI database available for ADR, drug Consumption and treatment results are insufficient to accurately represent the Indian population, thus all healthcare professionals—including those in rural areas—should be made aware of PV [22]. Physicians reported ADRs at a higher rate than pharmacists and other healthcare professionals. Due to a lack of assistance from the government and a small PV budget, PV reporting is difficult and timeconsuming [23].

Future goals

To raise awareness of ADR reporting and ensure that all Medical Council of India-approved institutions are covered by PvPI, all health care staff should receive advanced training at AMC. A strong system should be in place that can identify novel ADRs and produce data that will aid patients and healthcare professionals in making the best decisions. Patients themselves should be used as the source of information to determine the traits and risk factors of a patient. To improve regulatory compliance and clinical trial safety, good PV practises should be introduced as needed. The efficiency of PV systems should be increased using new and better technologies and procedures. Maintaining open communication with consumers also requires manufacturers to identify ADR correctly and to disclose it promptly [24, 25].

Conclusion

India's PV industry must overcome numerous obstacles in the coming years in order to develop and advance. India is the world's largest manufacturer of pharmaceuticals and a centre for clinical research;demands a PV setup that is more strict. Compared to the US and EU regulations,the Indian PV system currently lacks robustness and has to be improved. PvPI was a significant shift in the Indian PV sector,and it intends to broaden the breadth and reach of its operations in the years to come.The common causes of under reporting were a lack of understanding and awareness of the Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI), as well as laziness, indifference, insecurity, complacency, busyness, and a lack of training. In order to harmonise PV practises beyond regulation, it is necessary to define and put into effect "best suited practises" for the industry, regulatory agencies, and health-care practitioners. It calls for better communication mechanisms and formal training for PV professionals. Health care providers, manufacturers, customers, and various regulatory organisations all exchange safetyrelated information.

References

- Amale PN, Deshpande SA, Nakhate YD, Arsod NA (2018) Pharmacovigilance process in India: An overview. J Pharmacovigil 6:259.

- World Health Organization (1984) World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring, Geneva.

- Kim JH, Scialli AR (2011) Thalidomide: The tragedy of birth defects and the effective treatment of disease. Toxicol Sci 122: 1-6.

- Begaud B, Chaslerie A, Haramburu F (1994) Organization and results of drug vigilance in France. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 42: 416-423.

- Routledge (1998) 150 years of Pharmacovigilance. Lancet 351: 1200-1201.

- Sandeep B Bavdekar, Sunil Karande (2004) Protocol for National Pharmacovigilance Program. CDSCO Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India.

- Pharmacovigilance Program of India (2013) Guidance Document for Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting. 1:1-69.

- Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission Pharmacovigilance Program of India.

- Srivastava P, Kumar P, Sharma A, Upadhyay Y (2011) A review Pharmacovigilance importance and current regulations. Pharmacol Online 2: 1417-1426.

- Kalaiselvan V, Prasad T, Bisht A, Singh S, Singh GN, et al. (2014) Adverse drug reactions reporting culture in pharmacovigilance programme of India. Indian J Med Res 140:563-564.

- http://www.ipc.gov.in/PvPI/adr.html.

- Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission Pharmacovigilance Program of India.

- https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/export/sites/CDSCO_WEB/Pdf-documents/Consumer_Section_PDFs/ADRRF_2.pdf

- Fouretier A, Malriq A, Bertram D (2016) Open access pharmacovigilance databases: analysis of 11 databases. Pharm Med 30: 221-231.

- Craigle V (2007) MedWatch: The FDA safety information and adverse event reporting program. Journal of the Medical Library Association 95:224.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/76299/download

- (2018) European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency policy on access to EudraVigilance data for medicinal products for human use. Accessed.http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2016/12/WC500218300.pdf.

- Pacurariu AC, Coloma PM, van Haren A, Genov G, Sturkenboom MC, et al. (2014) A description of signals during the first 18 months of the EMA pharmacovigilance risk assessment committee. Drug safety 37:1059-1066.

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/403710/Healthcare-Professional-Yellow-Card-Reporting-Form_1_.pdf

- Lawrence Gould A (2003) Practical Pharmacovigilance analysis strategies. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety 12:559-574.

- Tandon V, Mahajan V, Khajuria V, Gillani Z (2015) Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a challenge for pharmacovigilance in India. Indian J Pharmacol 47:65-71.

- Khattri S, Balamuralidhara V, Pramod KTM, Valluru R, Venkatesh MP, et al. (2012) Pharmacovigilance regulations in India: a step forward. Clin Res Regul Aff 29:41-45.

- Biswas P, Biswas AK (2007) Setting standards for proactive pharmacovigilance in India: the way forward. Indian J Pharmacol 39:124-128.

- Businaro R (2013) Why we need an efficient and careful pharmacovigilance? Journal of pharmacovigilance.

- Jose J, Rafeek NR (2019) Pharmacovigilance in India in comparison with the USA and European Union: Challenges and perspectives. Therapeutic innovation & regulatory science 53:781-786.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Tom A, Joseph R, Pingat P, Harinarayanan (2023) Pharmacovigilanceand Clinical Safety: Comparison between India, US and Europe-A Review. Int JRes Dev Pharm L Sci, 9: 151.

Copyright: © 2023 Tom A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed underthe terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricteduse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author andsource are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 1404

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Nov 25, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1261

- PDF downloads: 143