Review Article Open Access

Persistence of ‘Survival Skills’ as a Risk Factor for Suicide in Severely Traumatised Individuals

Vito Zepinic, PhD*Psychclinic P/L, London, UK

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

Although suicidality is not a diagnostic criterion for PTSD, in clinical practice this condition is often present in particular with those patients who had experienced prolonged or repeated traumatisation. Severely traumatised patients might find suicide as an ‘emergency solution’ in order to escape from the ‘persistence of trauma environment’ that continues into the post-trauma time. Chronic trauma causes identity diffusion, fragility and a feeling of discontinuity, with severely disrupted/shattered self-cohesion, interpersonal relationships and existence. In this study among 24 severely traumatised patients (prisoners of war) it was found evidence of the persistence of five ‘survival skills’: betrayal/detachment, untrustworthiness of perception, traumatic moment, mobilisation for danger, and non-aliveness/vitality which could be a risk factor for the suicidality.

Keywords

Suicide, torture, ‘self-at-worst’, ‘survival skills’

There is only one serious philosophical problem: that is suicide.

Albert Camus (1942): Myth and Sisyphus

Suicide as a phenomenon which remains among the most tragic consequences of any mental state or disorder and the assessment of suicidal potential (suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, self-harm, etc.) should be of the highest clinical priority to treat. Identifying the individuals of a high risk for attempting or committing suicide expands the clinician’s reference in assessing and treating suicidal patients and their risk in life more seriously than any other mental problem. We can conceptualise suicidality as a disturbance of self-cohesion and continuity which is caused by an individual’s broken spirit and will to thrive, making the affective state flat and non-expressive – inert, lifeless, empty, worthless, and vacuous. Although suicidality is not a diagnostic criterion for PTSD, in severe and complex cases of the psychological trauma this problem appears quite frequently. The psychological trauma consequently impacts all aspects of selfstructure – one’s image of the body; the internalised images of others; and one’s values and ideals – and leads to a sense that self-coherence and self’s goals are invaded, assaulted and systematically broken down (Zepinic, 2004).

Traumatic events overwhelm ordinary human adaptations to life and generally involve threat to life or bodily integrity. A close personal encounter with severe violence, threat and death, confronts trauma victims with the extremities of hopelessness and helplessness, terror, disconnection, disempowerment, and evoke the response of inescapable catastrophe (Zepinic, 2008). Restoring feelings of the self-cohesiveness is not an easy task, especially with the victims of a human-designed aggression and violation. The vulnerable selfstructure of the traumatised individuals could be evidenced in the following aspects (1) difficulties in self-regulation, such as self-esteem maintenance, affect tolerance, a sense of self-cohesion and continuity, or the sense of personal agency; (2) appearance of symptoms, such as frequent upsurges of fears and anxiety, depression, or irritability; and (3) the individual’s reliance on primitive or less-developed forms of the self-object relatedness with attachment figures.

When the basis of self-structure and its organisation are damaged by the trauma, the aftermaths of the trauma may occur in various forms and degrees of the self-dissolution, fragmentation, disintegration, and self-destructiveness. Trauma survivor with a severely disordered or depleted sense of self may find suicide as an ‘emergency solution’ in order to escape from the vulnerable and unhealthy self. This prolonged trauma-related condition we emphasise as a distal exposure to an event(s) and consequences which manifest most clearly in the aftermaths of a disaster. Traumatised individual who is suicidal presents his ‘self-at-worst’ state comprised without a safety net or access to the emotional resources. In terms of practical reality and given the complexities in the ways trauma unfolds over time, we assume that the perceived-life-threat aspects of the trauma are often one of the strongest predictors in the risk of suicide for a trauma survivor.

Depleted or shattered self has been afflicted with a sense of emptiness in painful intensity of traumatic memories, leading to suicide as desperate attempt to ‘fill a gap’, which imprints even further destructions of the self as it has ‘nothing inside’ (Baumeister, 1990; Yufit & Lester, 2005). It is also evidenced that the individual’s coping strategies are impaired due to his/her inability to discharge tension and the drives of the inner conflicts finding suicide as the only way out from underneath the burdens of tension and inner impulses (‘Everything is worthless, killing myself is the only option out of a misery’ – is a common comment made by severely traumatised individuals).

Severely traumatised individuals describe their loss of the selfstructure in different ways: they feel they are falling apart, losing their bearings, or ‘treading water in the middle of the ocean with nothing to hang on to’, they may feel lost in space, or even feel non-existing. For the clinicians it is significant to recognise the patient’s use of negative terms when describing an experience of the fragmentation of the mind-body-self (van der Hart, O., et al. 1993). In some extreme cases of dissociation caused by trauma, the patients would report dissociated parts of the body and that their body has become ‘strange’ or ‘foreign’ to them. Trauma may lead to a sense of de-centering of the self, loss of groundedness and a sense of sameness, continuity of the ego-fragility, leaving scars on the one’s ‘inner agency’ of the psyche (Zepinic, 2012). Fragmentation of the self-identity has consequences in the patient’s psychological stability, well-being, and psychic integration resulting in proneness to disintegrated personality as a whole (Ulman & Brothers, 1988; van der Kolk et al., 1996; Wolf, 1988; Zepinic, 2008). In many cases it is apparent that fragmentation of the self-identity is a fracture of the soul and spirit of the person, like a broken connection in the patient’s existential sense of the meaning and existence.

Discontinuity of the self-cohesion shows a loss in strength, energy, and autonomy. Moreover, the destruction of self-structure results in self disunion, and/or disjoining of the interrelated dimensions of the self. The traumatised individual is unable return to the pre-trauma adaptive capacities, values, and goals due to unresolved and powerful inner conflicts. There is a ‘broken system’ for a new relationship, and coping style still rely on the mechanisms that have been used during the traumatic experience – ‘survival skills’. Keeping trauma-related coping mechanisms (‘survival skills’), the individual develops ‘broken relations’ – a here-and-now circumstances and the orderliness of daily living which is profoundly altered in ways associated with a sense of psychic disequilibrium. As the self is unadjusted to new life circumstances, trauma ‘survival skills’ become the essential and powerful factor in formatting individual’s personality changes. The longer the individual has been exposed to traumatic experience, the stronger his/her needs are for the ‘survival skills’. This damages the self-cohesion and trauma survivor feels insecure, helpless, and inadequate, hateful and hostile towards his/her own self. Without ability for the self-continuity and continuum of trauma survival skills, the survivor is fearful, uncomfortable, horrified, vulnerable, and self-destructive (Zepinic, 2009).

In pathogenic environment, the attachment is disturbed and instead of bringing psychic gain and equilibrium, the post-trauma time brings an aversive result with no posttraumatic growth. The experience and expression of the core affective phenomena face with disruptive, non-facilitating responses from attachment figures. Authentic self-expression meets with the other’s anger or ridicules which elicit a second wave of the trauma survivor’s emotional reactions: fear and shame. Disrupted attachment ties and compromise self-integrity, leading to an unbearable emotional state: experience of helplessness, loneliness, confusion, emptiness and despair.

The damage to self-identity and integrity results in a person’s ‘self-at-worst’ state scenario: at this point the individual is at the most depleted level of the sense of self, with no safety net and thus no access to the emotional resources. Unable to impose ‘survival skills’, he attempts to escape the excruciating experience of this unbearable emotional state, and is overwhelmed by the deadly and dangerous seeds of the development of psychopathological condition – commitment of the suicide. The traumatised individual comes to a conclusion that any responses other than suicide will catastrophically threaten to the self-integrity and/or the attachment ties. Suicide can be emphasised as a conscious act of self-inflicting, self-intended cessation; an act of the self-induced annihilation. Whatever else suicide is, it is a conscious act, but on the other hand, the driving force is an unconscious process. The patient’s unconsciousness is an important construction in the understanding a complicated human act, as suicide is imposed by mental constriction of existing emotional pain, hopelessness, and distortion (Shneiden, 1985).

The empty and shattered sense of self consists of one’s passivity, depressiveness and evident depletion in energy. Chronic trauma causes an identity diffusion, fragility and feeling of discontinuity, with severely disrupted/shattered interpersonal relationships and existence. As a response to the trauma circumstances, many survivors have a cluster of specific symptoms: ‘survivor’s syndrome’ which shows its existence even long after the trauma is over. Trauma experience can lay dormant in the deeply unconscious state of the psyche for many years until a trigger event(s) awakens it. In the post-trauma time, the patient’s relatedness and aliveness may still be based on ‘survival skills’, acquired during the traumatic experience. The patient’s behaviour, thoughts, and emotions are still attached to the traumatic past, without an existing ‘here-and-now’ state (Zepinic, 2001).

Method

Participants

The study was conducted with 24 patients who were reported for an assessment and treatment following their history of the ‘treatment-resistant PTSD’. Although, the term ‘resistance to treatment’ may vary widely, we emphasised that the ‘treatment resistant PTSD’ applies to those patients who did not show progress in their condition, in spite of being adequately treated (pharmacological, non-pharmacological, or combined) for more than 12 months (Zepinic, 2004). All subject involved in this study reported of being imprisoned or detained, tortured and interrogated during the war in former Yugoslavia1.

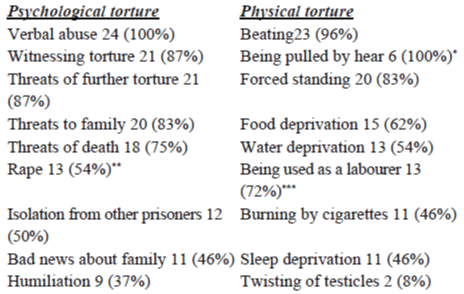

Despite being already diagnosed of suffering PTSD, all participants were re-assessed in regard to the type of their traumatic experience (psychological and physical torture), and suicidality (suicidal attempt(s), ideation, and/or self-harm). The group subjects mean age was 45 years (SD=8, range 24-66) and all of them have already been prescribed with medication in response to the diagnosis of PTSD, and other trauma-related disorders (depression, personality disorders, psychosis). There was no reported history of the alcohol abuse or drugs dependency prior to the imprisonment, however, 17 patients reported heavy drinking problems since their release from the prison. Participants reported no prior history of any crime, prosecution or imprisonment, and there was no history of any mental problems before the war. The medium duration of the time spent in prison was 1.3 years (range between 1-37 months), and 80% of the subjects reported having experience a mean of 18 different types of torture experience. The most commonly reported methods were psychological torture (threat, swearing, being forced to witness others being tortured), and physical torture (beating, falanga, cold-water shower, cutting a wound with a knife, and burning with cigarettes).

Measures

All participants were screened (in spite of already being diagnosed with a chronic PTSD) by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID), translated and standardised MMPI, and Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS), in an attempt to identify as much as possible the circumstances of traumatic experiences, the profile of PTSD diagnosis, symptoms complexity and severity, and levels of the personality impairments. To assess the patients’ suicidality, alongside a clinical interview, we administered Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation. Assessment and diagnosis had been made by trained clinicians (clinical psychologists or registrars in psychiatry) on the basis of structured clinical interview, without the involvement of an interpreter (clinicians were multilingual speaking).

Procedure

Psychometric testing and clinical interviews were performed in order to examine the presence and severity of PTSD symptoms, despite the already provided pharmacological treatment for such conditions, but without evidence of improvement and treatment resistance. Clinical interviews, as well as subsequent therapy sessions provided, have focused attention on the personality disturbances (thoughts, emotions, behaviour), and distorted relationships and the attachment with the others. In particular, we targeted the levels of ‘survival skills’ during the traumatic experience of torture and the presence of such skills at the present time. We hypothesise that still existing ‘survival skills’ is a factor for treatment resistant state and construct of the ‘self-at-worst’ which might cause suicidal ideation, attempt, and/or self-harm. We define the most simplistic definition of treatment resistance as a failure to achieve targeted goals and sustain a mental equilibrium what our patients did not achieve despite being treated for chronic PTSD more than 12 months (in medicine, the phrase ‘resistance to treatment’ is used to define the patient’s failure to respond to a standard form of treatment).

The chronicity of the symptoms in complex trauma may appear as a protracted syndrome or unremitted condition that makes a constant state of negative affective and physiological activity. These coexist with a high level of betrayal and a destructive sense of value in ideas, ambitions and activity of daily living (Zepinic, 1997). The trauma experience persists as a relievable nightmare, and consciousness remains fixed upon it. The quality of reality drains from the ‘here-and-now’ and death seems more realistic than living. Alongside with the administration of the psychometric instruments, during the clinical interview every patient was asked about his/her suicidality either of the self-harming, suicidal ideation or attempts. The survivors of severe trauma are often in a stage of severe depressed mood characterised by a chronic and fluctuating state of depression, hopelessness, loss of self-respect, and loss of energy for living (sense of meaninglessness).

The patients were encouraged writing about their traumatic event(s) and their resistance (self-defensive responsiveness) not to give up a life during the torture imposed. They were also asked to describe their vivid memories of the traumatic experience and current persistence of their ‘surviving skills’ including distortion of perceptions and judgement, persistence of the untrustworthiness of the perceptions, and difficulties in adjustment to the normal life and safe environment. Albeit the traumatic experience was over, being severely traumatised, they lost desire for aliveness and vitality with hostile and mistrustful attitudes towards the own self and others, a chronic feeling of being on the edge (Allen, 2005; van der Hart, & Dorahy, 2009).

Results

The participants (six women and eighteen men) reported exposure to eighteen different forms of torture during their imprisonment. Overall, they reported a total of 309 exposures ranging from 11% (twisting of testicles) to 100% (verbal abuse, and being pulled by hear).

*This torture was reported by all female subjects included in the study.

**Six women were included in study (five of them reported of being raped), however eight men also reported of being raped describing profound guilt and shame regarding the matter/event.

***All prisoners who reported being used as a labourer were male.

Sex comparisons across the reported type of torture showed significant differences between the genders:

• men were mostly exposed to physical torture (beating) accompanied with a verbal abuse, had been used as a labourer, were injured, or exposed to food, water and sleep deprivation, forced to witness torture, saw injured or killed person.

• women were exposed to the sexual assaults, traumatic news about a family member, threatened to further rape, pulled by their hear, or have been interrogated about husband or family member. Women also spent much less time imprisoned - maximum reported was 2 ½ months.

There were 17 patients (71%) who reported thoughts (ideation) of committing suicide during their imprisonment, but no suicidal attempt was reported. However, eight of them (47%) admitted of having at least one post-trauma suicidal attempt. Patients reported that hopelessness and life meaninglessness were key variables in their suicidality which we have conceptualised as a system of cognitive schemata having a common element of negative expectations for the future and maladaptive attitudes towards the post-trauma time. Patients described their expectations for the future with a focus on the anticipation of darkness, not obtaining good things, things not working out, their future being uncertain, and a general lack of enthusiasm, happiness, good times or anything related to hope (Zepinic, 2011). Loss of motivation included absence of all positive thinking, deciding not to want anything, and not trying to get something that was wanted.

Patients reported beliefs that they would not get better, nor solve personal problems, would have nothing to look forward to, would fail to achieve personal goals, and viewed the future with pessimism. In addition using MMPI2, patients showed a typical D-Pt personality profile (depression-psychosthenia), a syndrome characterised by fears, sadness, decreased emotional pain and working energy, low level of spontaneity and impulse control, disposition to self-accusation and self blame, worthlessness, hopelessness, high level of anxiety with severe psychosomatic and/or physical reactions, difficulty concentrating, insomnia, libido problems, loss of appetite, dichotomy in diagnosis (neurotic-psychotic, endogenic-reactive), fatigue and restlessness.

The patients included in this study reported persistence of numerous attitudes from their traumatic past into the ‘here-and-now’ circumstances, which had caused clinically significant impairments in their social, occupational, emotional and other areas of functioning. The persistence of the ‘survival skills’ illustrates that trauma victim does not have any stream of consciousness other than experiencing the sense of alienation from the ‘here-and-now’ environment and surroundings. As a part of the patient’s traumatic system, the ‘survival skills’ can be quickly re-activated by triggering factor, reminding the individual of failure, despair, emptiness, and worthlessness. Failures and feelings of being adrift in life create frustration and a depleted desire to live, which almost totally pervade the individuals’ life, characterised by pronounced sense of the emptiness - a lack of purpose or goals. Thoughts of self-destruction were more about a desire not to live, rather than a desire for committing suicide.

We recognised persistence of five main ‘survival skills’, a few of them had been in combined effect during the exposure to the traumatic experience, which overwhelmed the traumatised individual’s relatedness, emotions, thoughts, and behaviour towards themselves and others in post-trauma time:

• persistence of the betrayal/detachment

• persistence of the untrustworthiness of perception

• persistence of the traumatic moment

• persistence of the mobilisation for danger

• persistence of the non-aliveness/vitality

Persistence of the Betrayal/Detachment

Severe trauma can induce a wholesale destruction of desire, loss of faith and the will to exist and have a future. Betrayal of ‘what is right?’ is particularly destructive to a sense of self-continuity, of values in ideals, ambitions, things, and activities. In such circumstances when some major ideals have been betrayed, the trustworthiness of every external idea or inner cohesion comes into question. The loss of self values and respect, as well as respect of the entire world, delivers a loss or lack of energy and motives for living. Even the value of one’s own living place, town or state, can become lost. Alienation from valued images of friendships or relationships, attachment and togetherness may contribute to the fact that life existence is without of any value. Safe and nonviolent attachments to others become virtually impossible for severely traumatised individuals. The persistence of betrayal was the most evident ‘survival skill’ still among the patients as 16 or 66.7% of them reported of being disturbed by it.

The persistence of betrayal/detachment ‘survival skill’ is characterised by a chronic condition of the hopelessness and social withdrawal. The trauma victim can be deeply buried inside – superficially preoccupied with the own failure and condition that ‘no hope and cannot be changed’, as patients usually say. More often, such ‘no hopes’ merely externalise the inner impulses that lead to the entire disappointment with the self and others. Their ‘reality’ is an unfortunate experience in the past which is more influential than their current normal circumstances of the life. Similarly, preoccupation with failures in the past urges the suicidal thoughts – with or without action – point pervasive hopelessness even if patient presents a façade of optimism (Zepinic, 2012). A general lack of the initiative is an indication that the patient is in deep unfortunate condition; his insight is very painful bringing despair, unwillingness and discouragement to go through the hardship of again working through a new problem.

Persistence of the Untrustworthiness of Perception

Severe trauma strikes even the most basic functions of the trauma survivors, including their perceptions and judgement. Among the patients, 11 or 45% reported characteristics of the untrustworthiness of perception ‘survival skill’, and three of them reported significant alteration of self-awareness (dissociative state) and confusion about self identity. It is common that extremely horrible experience attacks the basic mental state of intention, anticipation, and perception. The cumulative effect of severe, prolonged or repeated attacks on mental function is to undermine the trauma survivor’s trust in own perception, making confusion regarding existence and reality of the objects or events. The traumatised individual may get to the point where he/she is not even sure about place or people who imposed the torture and trauma. In such situation, hypervigilance is a rational response and everything must be checked to be sure that it is what it appears to be, leading the individual to the obsessive-compulsive state of mind.

Some loss of the trustworthiness of perception may be purely physiological (due to physical injuries during traumatic experience), dissociative, or a result of the patient’s inability to filter out trivial or harmless sensations from reality (Shneiden, 1985; Williams, 1997). This could be a result of consistently suppressed emotions and thoughts about the danger making trauma survivor’s post-trauma time and day-to-day functioning miserable, and in limbo. In essence, this condition is characterised by the self/outside world relationships with the patient’s subjective state of unreality in which there is a feeling of estrangement, either perception of the own self or the external environment. The essential features of the untrustworthiness are episodes of detachment or estrangement from the one’s present self. This condition is characterised by unpleasant state of disturbed perception in which external objects or parts of the one’s body are experienced as changed in their quality, remote or automatised. It is common that severe trauma causes symptoms of derealisation leading to diagnosis of having psychotic features. However, it is recognised that the patient’s reality is intact (awareness is only a feeling not reality of automaton), but the traumatised individual cannot overcome it.

Persistence of the Traumatic Moment

Many severely traumatised individuals make their first contact with the mental health professionals due to their fear of suffering insanity. Their concern is also often related to profoundly disturb bodily functioning, such as involuntary movement, or loss of bladder or bowel control despite not having any confirmed organic abnormalities (somatoform dissociation). The trauma survivor is unconscious of the trauma moments imprinted into his/her memory system during the traumatic event. As long as the traumatic moment persists as a reliable nightmare, consciousness remains fixed upon it. The experimental quality of reality drains from the ‘here-and-now’ circumstances finding suicide a better solution than to struggle with dysfunctional state. This is an aspect of the detachment of the trauma survivor from the current life and is intimately connected with the persistence of emotional numbness developed during the traumatic experience

With severely traumatised individuals, the traumatic memory is not narrative but rather it is as experience which re-occurs either as a full sensory replay of traumatic event(s) in dreams or flashbacks with all things seen, heard, smelled, and felt intact and present, or as disconnected fragments (Burke et al. 1992; Buttler & Spiegel, 2004; Herman, 1992; Zepinic, 2008). These fragments may be of inexplicable rage, terror, or disconnected body states and sensations, sensations of suffocation in prison cell or being tumbled over and over by rushing toward shelter – but without any memory of either a cell or a shelter. In other instances, the memories of facts may be separately preserved without any emotion, meaning or sensory content. Often the severely traumatised individual is able to give an utterly blind statement of a fact slipped into another context. The clinician must bear in mind that when the traumatic moment re-occurs as flashbacks or nightmares, the emotions of trauma (terror, rage, and grief) may be merged with one another. Such emotions are in fact relived not remembered, as the trauma victims lose authority over their memories during traumatic experience.

Many clinicians are of the opinion that complex trauma can be described as a disorder of the memory because of the intrusive trauma recollections that are such a prominent feature of the disorder: the memory is distressing and involuntary characterised as being triggered or revoked spontaneously by the exposure to trauma cues, as being fragmented containing prominent perceptual features, and as involving an intense reliving of the event in the present (Friedman et al., 2007). Alongside with the other ‘survival skills’, all our patients reported persistence of the traumatic moment making them dysfunctional and unable to cope. This is entirely unconscious state of inner tyranny with a stage of self-hate as a failure that the self is unable to prevent itself from the traumatic memories impact.

Persistence of the Mobilisation for Danger

Vigilance, the mental and physical preparation for the attack is the most disturbing trauma-survivor’s behaviour which invades everyday life profoundly. One of our patients reported that since his release from the war-prison, he has always slept in a room, the corner opposite the door ‘expecting that the perpetrator could enter the room at any time’. The patient appeared with self-defensive

responsiveness and for him there was no place to completely shed vigilance. The sound of door lock click in any other room creates an explosion of uncontrollable fear and he would immediately hit to the ground floor unaware of his action. The most evident sign of the vigilance is the patient’s intolerance to having anyone come unannounced from behind. Exposed to the continuous threats of danger, the trauma survivor remains mobilised for his survival indefinitely without having physical calm or comfort.

Over the time, the trauma survivor’s body may appear of developing various somatoform symptoms (pain on different body parts, tremors, choking sensations, rapid heartbeat, or gastrointestinal disturbances, or sexual impotence). Some severely traumatised individuals may become so accustomed to their vigilance that they categorically deny the connection between bodily symptoms and the nature of trauma in which these symptoms were formed (Bremmer, 1997; Brockway, 1988; Herman, 1992; Zepinic, 2010). Persistence of expectation for danger is an inescapable terror, without the possibility to make any future plan, but rather lay focus on the ‘now-moment’, as it was during the traumatic experience in order to survive. A depleted state of self-continuity, apathy and an inability to want anything than to ‘survive’ persists into present life. The trauma survivor’s certainty is the unpredictable negating narrative consciousness assumed by the current circumstances.

Persistence of the Non-Aliveness/Vitality

When trauma survivor loses all sense of meaningful personal narrative, he develops a contaminated identity or a punishing identity. Dysfunctional sense of aliveness/vitality is driven by the unconscious needs and wishes from the past, which play a greater role on the traumatised individual than the present time. Pathological forms of aliveness/vitality are identified by the disturbances or alterations in the normally integrative functions of the memory, identity, or consciousness. In essence, these pathological forms represent a failure to integrate aspects of the perception, memory, identity, and consciousness into the present time, showing ‘feelings of strangeness’, or ‘spacing out’ (Zepinic, 2010). The patient does not have control over the past (in fact, the past controls patient) experiencing a sense of hopelessness and loss of control over the body. This makes for a dual function within the same individual, delaying integration into present time as trauma itself is regarded as a discontinuity of life existence.

The duplicity makes diffuse impairment of the sense of truth and contributes both an alienation from the own self and great dependency from the inner complex drives. In essence, the traumatic past holds a huge role in determining here-and-now existence; the patient’s ‘presentness’ is defective and a ruptured practice of everyday life, which seems difficult and unlikely to move from the influence of the past. The trauma experience is mirrored and, when having a memory about the past, whatever a happening now is actually a conviction of the past.

Many of our patients – war-prisoners – stated that those who died during the war were lucky and blessed by God. They said that God kept them alive to torture them ‘If God had loved me, He would have let me die with my brother’ – stated one of our patients. The trauma causes a loss in the patient’s desire for aliveness and vitality, hostile or mistrustful attitudes toward the self and others, a chronic feeling of being ‘on the edge’ (Allen, 1995; van der Hart, et al., 2009; Wolf, 1988; Yufit & Lester, 2005; Zepinic, 2012). This sense of vulnerability can lead to the anticipatory danger and catastrophic expectations due to the complex self-organisation and perpetuate feelings of disconnectedness.

When an individual has been tortured or personal boundaries have been violated or otherwise assaulted, through starvation, water or sleep deprivation, or simple witnessing the torture or killings or any other circumstances impossible to escape, the body and mind react with a fear and rage, and the mind undergoes a distinctive kind of non-aliveness. This could lead to the self-hate state which constitutes the individual’s inability or lack of desire to re-store self-continuity which is seriously damaged. With duplicity as the individual’s response to the self-hate, the individual alienates himself in twofold ways: by forcing to falsify his feelings instrumented by inner conflict drives, and beliefs of endangering by the external world. The entire response in fact is determined by the self-hate and realisation of the trauma victim’s inability to comply with the external demands appropriately unless responding in self-hate response with the suicidal ideations or self-harm. In another way, the trauma victim’s unconscious reactions are ultimate response saying that the self in its duplicity is unnatural and cannot be transformed into pre-trauma stage.

Discussion

Little is known about factors associated with a suicidal risk of PTSD. This clinical study provides a step toward understanding broad categories of factors that may be implicated in development of suicidal thoughts in severe traumatised individuals. Without any doubt, the captivity and the war-imprisonment cause a significant impact on one’s personality and self-structure. Because of the timeless and unintegrated nature of the traumatic memories, trauma victims remain embedded in the trauma as a contemporary experience, instead of being able to accept it as secondary and belonging to the past (Zepinic, 2008). The meaning of the traumatic experience evolves over time, and often includes feelings or irretrievable loss, anger, betrayal, and hopelessness. Thus, clinicians treating severe traumatised individuals should be aware that suicidality may constitute one of the most important clinical symptoms cluster to investigate.

The participants in this study, who have been imprisoned during war in former Yugoslavia (six women and eighteen men), have reported 18 different types of torture which they have experienced during their imprisonment/detention which caused an extraordinary impact upon the trauma survivors’ post-trauma life. As we hypothesised, there were differences of torture types imposed upon the war-prisoners: most imprisoned men had been exposed to physical torture (beating) accompanied by verbal abuse, they were used as a labourers, exposed to food, water and/or sleep deprivation, and forced to witness torture done onto others. On the other hand, women reported being raped (83% of them included in this study), heard horrible news about family members, were threatened to be raped, and have been interrogated about their family members.

Considering reported psychological and physical abuse and torture during imprisonment it is evidenced that a constant fear of death or injury, and uncertainty of tomorrow have been reminded over to the present time. The trauma victims had experienced feelings of the worthlessness and dehumanisation leading them to rely on the ‘survival skills’ which have usually continued long period after the trauma is over. It should be emphasised that the prolonged psychological effects of trauma are often experienced in combination during the traumatic experience and have continued to exist the same manner in the post-trauma time. Persistence of the ‘survival skills’ is a dreadful condition as trauma survivors, in essence, are re-processing the traumatic event(s) and still have traumatic exposure such as the original traumata occurs again. Those individuals who had faced life threatening situation, had been tortured, witnessed grotesque form of torture etc., are more likely to continue experiencing these ‘survival skills’, as their traumatic memories are deeply unconscious. Furthermore, there is typical a dose-response relationship between the degrees of trauma exposure and the aftermaths of it.

The distorted self of the trauma survivor has to be reconstructed in the post-trauma time to accept the past as a past, and to integrate it into the present time, to become a whole and autonomous person not being led by the past and by drives of the inner conflicts. Unable to deal with memories of the traumatic past and overwhelmed by persistence of the ‘survival skills’ the trauma victims likely show pathology associated with self-destruction and hostility. It is evident that there is a complex subtype of PTSD, or other trauma-related disorders (psychosis, depression, personality disorders), with a wide array of the personality changes and symptoms, often leading the trauma survivor to the suicidality as an attempt to escape the ‘inescapable misery and horror life’ which is led by horrific traumatic memories and the presence, or co-occurrence (reminder), of the ‘traumatic past’ at the present time. Therefore, the complexity of re-processing traumatic event(s) may require that the clinician accomplish a thoughtful and creative tracing of the impact of traumatic stress longitudinally on the patient’s personality and all realms of mental and social dysfunctions, including thoughts or an attempt of the self-harm.

The situation of patient who had been a prisoner of war, with regard to the history of trauma experiences, may be different from the other PTSD patients, and accurate diagnosis requires an understanding of these various impacts. Patients usually vary greatly in presenting the level of awareness both of the PTSD symptoms and the persistence of the traumatic past. Traumatic event(s) may be repressed or dissociated – entirely or partly – however, the persistence of the ‘survival skills’ shows re-processing of traumatic exposure from the past in the present time. Patients show lack of awareness of such persistence and related symptoms, particularly avoidance symptoms, with an inability to recount their traumatic events with considerable clarity.

Due to the persistence of ‘survival skills’, the patients are often ‘treatment resistant’ in spite of provided therapy, they remain either explicitly or implicitly negative regarding traumatic event(s) and resulting symptoms. Lack of recovery may have insulted a barrier toward trust, which may be apparent in the outset of the therapy. Severely traumatised patients typically contain the intense impact emotions, either within or outside the awareness. These may include terror or horror deriving from violence or gruesomeness experienced in the traumatic events; shame or guilt deriving from the nature of horror or the patient’s actions or inactions; and an intense grief deriving from the losses (Blank, 1994). Trauma victims may be fearful of further possibility of harm or retaliation. Although these fears are unrealistic they are unconscious regarding persistence of their ‘survival skills’ about for lengthy periods of the time, in order to defend the self from further destruction.

Several study limitations should be noted here. The participants were a self-selected sample of the severely traumatised patients referred for the assessment and treatment due to no adequate progress in their treatment of PTSD (treatment resistant). Research is needed to verify whether the rates of war-related disorders (PTSD, depression, personality disorders) observed in our sample are representative enough to conclude that persistence of the ‘survival skills’ inevitable causes treatment resistance and suicidality. This study was not designed to provide prevalence estimates of these factors; rather, its purpose was to evaluate potential correlates of the ‘survival skills’ and suicidality in order to suggest needed avenues for the assessment and treatment of severe PTSD or complex trauma. This is an urgent clinical need for which little or no guidance is available from empirical analysis.

1In the early 1990s, the war in former Yugoslavia caused the biggest humanitarian crisis and migration in Europe since World War II: over 45% of the population from the war-affected territories were forced to leave their homes in internal or external migration. For several million people, the conflict was associated with various extremely stressful and traumatic experiences, including repeated and prolonged shelling, mass rape, imprisonment and torture, loss of family members, ethnic cleansing, and forced displacement.

2This form was adapted and was used in the patients’ language with no interpreter being involved. The test was an original version adapted in patients’ country of birth before war.

References

- Allen, J.G. (1995).Coping with trauma: A guide to self-understanding.American Psychiatric Press, Washington DC

- American Psychiatric Association (2000).Diagnostic and Statistical Manual ofMental Disorders, 4th edition (revised), Washington DC

- Andrew, B., Brewin, C.R., Philpott, R., &Stewart, L. (2008).Delayed onset posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review of the evidence.American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 1319-1326

- Baumeister, R.F. (1990).Suicide as Escape from Self.Psychological Review, 97, 90-113

- Blank, S.A. (1994). Clinical detection, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.Psychiatric Clinic of North America, 17, 351-384

- Boss, P. (2006).Trauma and Resilience. WW Norton: New York

- Bremmer, J.D. (1997).Trauma, memory, and dissociation. American Psychiatric Press: Washington DC

- Breslau, N., &Davis, G.C. (1987). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: The etiologic specificity of wartime stressors.American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 578-583

- Briere, J. (1997).Psychological Assessment of Adult Posttraumatic Stress. American Psychological Association: Washington DC

- Briere, J., &Spinazzola, J. (2005).Phenomenology and Psychological Assessment of Complex Posttraumatic Stress.Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5, 401-412

- Brockway, S. (1988). Case report: Flashback as a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom in a World War II veteran.Military Medicine, 153, 372-373

- Burke, A., Heuer, F., &Reisberg, D. (1992).Remembering emotional events.Memory andCognition, 20, 277-290

- Buttler, L.D., &Spiegel, D. (2004).Trauma and Memory.Review of Psychiatry, 16, 25-53

- Carlson, E.B. (1997).Trauma Assessment. The Guilford Press: New York

- Christianson, S., &Loftus, E.F. (1987).Memory from traumatic event.Applied CognitivePsychology, 62, 827-832

- Courtois, A.C., &Ford, J.D. (2009).Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorder. The Guilford Press: New York

- Foa, B.A., &Rothbaum, O.B. (1998).Treating the Trauma of Rape. The Guilford Press: New York

- Foa, B.A., Keane, T.M., &Friedman, M.J. (2000).Guidelines for the Treatment of PTSD.Journal of Posttraumatic Stress, 13, 539-588

- Foa, B.A., Keane, T.M., &Friedman, M.J. (2009).Effective Treatments for PTSD. The Guilford Press: New York

- Friedman, J.M., Keane, M.T., &Resick, A.P. (2007).Handbook of PTSD, Science andPractice.The Guilford Press: New York

- Herman, J.L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A Syndrome in Survivors of Prolonged and Repeated Trauma.Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3, 377-391

- Litz, B.T. (1992). Emotional numbing in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review and reformulation.Clinical Psychology Review, 12, 417-432

- Marmar, C.R., &Freeman, M. (1991).Brief dynamic psychotherapy of treating posttraumatic stress disorder.Psychiatric Annals, 21, 405-414

- Masterson, F.J. (1990).The search for the real self, The Free Press: New York

- Omaha, J. (2004).Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Emotional Regulation. WW Norton: New York

- Osuch, F.A., Noll, J.G., &Putnam, F.W. (1999).The Motivations for Self-injury in Psychiatric Inpatients.Psychiatry, 62, 334-346

- Pinto, P.A., &Gregory, R.J. (1995). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with psychotic features, Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 3, 207-213

- Schore, A.N. (2003).Affect regulation and the repair of self. WW Norton: New York

- Shneiden, E.S. (1985).Definition of suicide. Wiley & Sons: New York

- Singer, J.A. (2005).Personality and Psychotherapy. The Guilford Press: New York

- Ulman, B.R., &Brothers, D. (1988).The Shattered Self.The Analytic Press: New Jersey

- van der Hart, O., &Dorahy, M.J. (2009).History of the concept of dissociation. In Dell, P.F., O’Neil, J.A. (Ed.).Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders, Routledge: New York

- van der Hart, O., Steele, K., Boon, S., &Brown, P. (1993). The treatment of traumatic memories: Synthesis, realisation, and integration, Dissociation, 6, 162-180

- van der Kolk, B.A. (1987).Psychological Trauma, American Psychiatric Press, Washington DC

- van der Kolk, B.A., MacFairlane, A., &Weiseath, L. (1996).Traumatic Stress, The Guilford Press: New York

- van der Kolk, B.A., Roth, S.H., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., &Spinazzola, J. (2005).Disorder of extreme stress, Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18, 389-399

- Williams, L.M. (1997).Cry of Pain: Understanding Suicide and Self-Harm. Penguin: London

- Wolf, S.E. (1988).Treating the Self. The Guilford Press: New York

- Yufit, R.I., &Lester, D. (2005).Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of SuicidalBehaviour.Wiley & Sons: New Jersey

- Zepinic, V. (1997).Psychological characteristics of war-related PTSD (Chapter 10), In Ferguson, B., Barnes, D. (Ed.).Perspectives on Transcultural Mental Health, TCMH, Sydney

- Zepinic, V. (2001).Suicidal risk with war-related posttraumatic stress disorder (Chapter 14), In Raphael, B., Malak, A.E. (Ed.).Diversity and Mental Health inChallenging Times, TCMHC, Sydney

- Zepinic, V. (2004).Treatment resistant symptoms of war-related PTSD, Japanese Bulletin in Social Psychiatry, 13(4), 246

- Zepinic, V. (2008). Healing traumatic memories: A case study, DynamischePsychiatrie,5-6, 279-287

- Zepinic, V. (2009).The sense of self and suicidal behaviour, International Journal ofHealth Science, 3, 248-251

- Zepinic, V. (2010).Treating war-related complex trauma using the Dynamic Therapy.The International Journal of Medicine, 3, 384-390

- Zepinic, V. (2011).Hidden Scars: Understanding and Treating Complex Trauma.Xlibris, 2011

- Zepinic, V. (2012).The Self and Complex Trauma.Xlibris, 2012

- Zepinic, V. (2015).Human Rights Violation and Chronic Symptoms of PTSD.Canadian Social Science, 2, 1-7.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14356

- [From(publication date):

specialissue-2015 - Jan 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9865

- PDF downloads : 4491