Perinatal Outcome in Patients with Diabetes in Pregnancy and One Previous Caesarean Section: A Prospective Observational Service Evaluation

Received: 11-Jan-2019 / Accepted Date: 07-Feb-2019 / Published Date: 14-Feb-2019 DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000404

Abstract

Background: To determine the perinatal outcome in patients attending Joint obstetric and diabetic clinic who had diabetes and one previous caesarean section.

Methods: A prospective service evaluation was conducted in a secondary care hospital having approximately 5100 deliveries per year. The combined cesarean section rate during the study period for all pregnant women and for all diabetic patients were 31% and 60%, respectively. Patients attending joint obstetric diabetic clinic from July 2015 to July 2016 were considered for the study. Fifty five (55) patients with both pregestational diabetes and gestational diabetes requiring pharmacotherapy and one previous caesarean, out of 358 patients who attended the clinic, were identified. The perinatal care, including timing, mode of delivery and indication for Cesarean section, maternal and neonatal outcomes were studied.

Results: Out of 55 women, 8 (15%) had type 2 diabetes mellitus and 47 (85%) had gestational diabetes mellitus requiring pharmacotherapy. Initially, during antenatal follow up, 23 women (41%) were planned for vaginal birth after caesarean and 32(59%) were planned for elective cesarean section. Seven (7) women (13%) had a successful vaginal birth after cesarean section. These women had no additional risk factors and delivery was uneventful. Forty eight (48) women (87%) had cesarean section (elective, 60% and emergency, 27%). Eleven (75%) out of these 15 emergency cesarean section patients had additional risk factors that contributed to the decision for cesarean section. Most of the maternal complications 13/55 (23%) were in the cesarean section group and the majority were from emergency cesarean section group. Fifteen out of the fifty five cases (27%) were due to intra-uterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, eclampsia, abruption and postpartum hemorrhage. Similarly in all neonatal complications 14/55 (25%) were from the Cesarean section group (2 cases of small for gestational age, 6 cases of respiratory distress syndrome, 6 cases of Large for date). Among the 8 type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, 7 delivered by Cesarean section (4 emergencies and 3 elective) and only one had a successful vaginal birth after cesarean section. All 4 of the emergency Cesarean cases had additional risk factors.

Conclusion: We found an exceptionally high caesarean section rate of 87% in our study which is almost twice as high as was found in the general diabetic pregnant population from other studies. Our study is the first of its kind to determine the cesarean section rate and perinatal outcome in combined pregestational and gestational diabetic patients requiring medical treatment and with one prior cesarean section. This study highlights the need for multi-centered studies to determine the optimal cesarean section rate that affords the lowest perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality and also on how to modify these confounding factors so as to decrease the high caesarean section rate amongst this high risk group of patients.

Keywords: Diabetes; Gestational; Vaginal birth after caesarean; Pregnancy in diabetics

Abbreviations

CS: Caesarean Section; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; VBAC: Vaginal Birth After Caesarean; NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; LGA: Large for Gestational Age; SGA: Small for Gestational Age; WHO: World Health Organization; RDS: Respiratory Distress Syndrome; PPH: Post Partum Hemorrhage; IUGR: Intrauterine Growth Retardation; BOH: Bad Obstetric History; ERCS: Elective Lower Segment Caesarean Section; PROM: Premature Rupture of Membranes

Definitions

GDM was diagnosed as per our hospital guideline, which is based on WHO 75 gram OGTT.

Diagnostic criteria are based on International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG) threshold.

Diagnosis is made of GDM when any of these glucose values are exceeded.

GDM-Fasting ≥ 5.1 mmol/l (92 mg/dl), 1 h ≥ 10.0 mmol/l (180 mg/ dl), 2 h ≥ 8.5 mmol/l (153 mg/dl)

Criteria for Diagnosis of Overt Diabetes.

Diagnosis is made when any of these glucose values are exceeded.

Using 75 g OGTT Other Criteria Diabetes Fasting ≥ 7.0 mmol/l (126 mg/dl), 2 h ≥ 11.1 mmol/l (200 mg/dl)

HBA1C ≥ 6.5% ≥ Random blood glucose 11.1 mmol/l (200 mg/dl) in symptomatic patients.

PPH: Blood loss ≥ 500 ml in case of vaginal delivery and ≥ 1000 in case of caesarean section

Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia: Was defined based on ISSHP guideline 2014.

Systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and or a DBP ≥ 90, with no evidence of pre-existing hypertension and the absence of proteinuria.

Preeclampsia was defined as a combination of gestational hypertension with proteinuria (≥ 300 mg/24 h).

Eclampsia was defined as presence of convulsions in a patient with preeclampsia

Large for date was defined as a birth weight above the 90th percentile adjusted for gestational age, gender, parity and ethnicity.

Small for date was defined as birth weight below 10th percentile adjusted for gestational age, gender, parity and ethnicity

Polyhydramnios: Single deepest pocket ≥ 8 cm or amniotic fluid index ≥ 24 cm

Intrauterine growth retardation: Is defined as an Estimated Foetal Weight (EFW) or Abdominal Circumference (AC) less than the 10th centile.

Background

Diabetes in pregnancy, either gestational or pre-gestational is increasing globally. In the Gulf region, due to diversity of population, it is increasingly a major health problem. Different studies have shown different incidence using different diagnostic criteria but it ranges between 6.4-16.3% [1,2].

Diabetes in pregnancy is associated with increase in both maternal and fetal complications as well as increase in the rate of Caesarean Section (CS) as compared to general obstetric population [3,4]. Higher caesarean section rate in diabetes can be due to several additional risk factors in this group of patients like advanced maternal age, medical complications, previous poor obstetric history, preferences of patients and prevailing clinical practice of the particular institution.

Due to an increasing rate of caesarean sections worldwide the focus is on primary caesarean sections and in patients who had previous one delivery by caesarean section. Diabetes per se is not an indication for caesarean section however all the studies show a higher caesarean section rate compared to the non-diabetic obstetric population even though the reasons for these are not clear [5].

The reasons for the rising rate of cesarean section worldwide are multifactorial and still not fully understood. WHO for many years recommended a cesarean section rate not exceeding 10 to 15 percent based on a consensus opinion however more recent studies indicate that the optimal cesarean delivery rate taking into account the lowest maternal and neonatal mortality rates should be approximately 19 per 100 live births [6].

There is increasing advocacy for a renewed effort in finding ways to reduce the high cesarean section rates, these include performing external cephalic version for breech at term, training and performance of advanced operative vaginal deliveries and even recently as reported in a Portuguese study has showing a reduced national cesarean section rate after a concerted effort through the transmission and sharing of key maternity indicators such as cesarean section rates, rates of instrumental vaginal deliveries, perinatal and maternal mortality rates and training of health care professionals [7-9].

The optimal cesarean section rate in diabetic patients requiring pharmacotherapy is not known and the same applies to these diabetic patients on treatment with a prior cesarean delivery.

There are only a few studies which have looked at vaginal birth after caesarean in patients with diabetes and all look at perinatal outcome including cesarean section rates in patients with gestational diabetes only [4,10,11].

In view of the paucity of literature which has looked into the perinatal outcome of patients with diabetes in pregnancy (both gestational and pre-gestational) on treatment and who have had their previous delivery by caesarean section, we at our institution, decided to look in to this by doing a prospective service evaluation.

Methods

This prospective observational service evaluation was conducted in a secondary care Hospital in Hamad medical Corporation Qatar. In this hospital we have a dedicated joint obstetric diabetic clinic which is run jointly by obstetricians, endocrinologists, diabetic educators, nurses and dieticians. All the patients who have diabetes in pregnancy whether pre-gestational or gestational and requiring treatment such as oral hypoglycemic or insulin or both are looked after in this clinic.

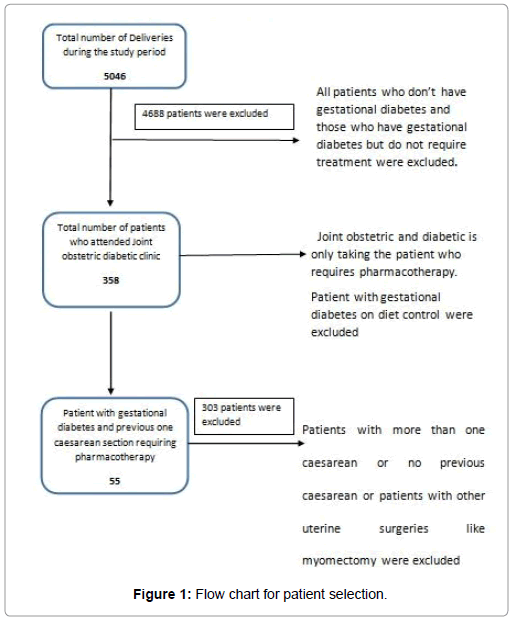

All the patients who attended the clinic from July 2015 to July 2016 and had previous one delivery by cesarean section were included in this study (Figure 1).

Data collection

Data was collected from electronic medical records. A total of 358 patients attended the clinic during this period. Out of which 55 patients had one previous delivery by cesarean section and were receiving pharmacological treatment to control blood sugar. During this period the total no of deliveries in the hospital were 5046.

Maternal outcome

Obstetric outcomes studied were gestational age at delivery, counseling and plan of delivery in antenatal clinic, final mode of delivery, indication for cesarean section and additional antenatal complications like preeclampsia, Intrauterine Growth restriction (IUGR), antepartum hemorrhage and Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH).

Neonatal outcome

Neonatal outcome studied were gestational age at birth, birth weight, Apgar score, admission to NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit), Small for Gestational Age (SGA), Large for Gestational Age (LGA) Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) anomalies and birth trauma if any.

Results

Total numbers of deliveries during the study period were 5046. The combined caesarean section rate for all pregnant patients in the hospital during this period was 31% while caesarean section in all patients with one previous caesarean was 61% (Table 1).

| Parameters | No of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of delivery during study period | 5046 |

| Total Caesarean section rate during study period | 31% |

| Total Caesarean section rate of patients with previous one caesarean during study period | 61% |

| Total number of patients attending diabetic clinic | 358(7%) |

| Total number of patients in study group | 55/358(15%) |

| Total number of gestational diabetes patients | 47/55(85%) |

| Total number of pre- gestational diabetes patients | 8/55(15%) |

| Caesarean section rate in study group | 87% |

| Nationality | |

| Indian subcontinent | 38(69%) |

| Middle east | 17(31%) |

| Others | 5(<1%) |

| Parity | |

| Para 1 | 41(76%) |

| Para 2 | 7(12%) |

| Para 3 or more | 7(12% |

| Gestational age at delivery | |

| <36 | 3(5%) |

| 36-38 | 10(18%) |

| 38 or more | 42(77%) |

| Birth weight | |

| <2.5 kg | 3(5%) |

| 2.5-3.5 kg | 33(61%) |

| 3.5-4 kg | 15(27%) |

| > 4 kg | 4(7%) |

| Mode of delivery | |

| VBAC | 7(13%) |

| Elective caesarean | 33(60%) |

| Emergency caesarean | 15(27%) |

Table 1: Demographic data.

Total number of patients who attended our diabetic clinic for treatment during study period was 358, which is 7% of total deliveries. Fifty five (55) patients from 358 met the criteria of previous one delivery by cesarean section and diabetes in pregnancy with pharmacotherapy for blood sugar control.

Eight out of fifty five (8/55) (15%) of patients were with pre gestational diabetes and 47/55 (85%) gestational diabetes who required treatment (Table 1).

Table 1 also shows demographic data of our study population. Based on our hospital guideline for diabetes in pregnancy which is based on NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines all patients were counselled including mode of delivery by 36 weeks of gestation and a plan of care was documented in the medical records [12].

Table 2 shows the perinatal and maternal outcomes. Initially 23/55 (54%) were planned for VBAC (vaginal birth after caesarean) and (42%) 30/55 were planned for elective caesarean. Four percent (4%) delivered before 36 weeks but 11 out of 23 patients planned for VBAC entered labor and 7 of them achieved a successful vaginal birth resulting in a VBAC rate of 64% for those who had trial of labor. This is similar to the VBAC rate in our general obstetric population.

Out of the 8 babies that needed admission to NICU, 2 required non-invasive respiratory support due to RDS. Length of stay was 2-8 days, one baby was diagnosed with neonatal jaundice due to ABO incompatibility and one had suspected sepsis with no proven as shown in Table 2.

| Maternal complications 13/55 | Total no. of cases | Neonatal complications 14/55 | Total no. of cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhydramnios | 4 | NICU Admissions | 8 |

| Preeclampsia | 2 | RDS | 6 |

| Hypertension | 2 | SGA | 2 |

| Eclampsia | 2 | LGA | 6 |

| IUGR | 1 | Congenital anomalies | 1 |

| Abruption | 1 | Sepsis | 1 |

| PPH | 1 | Neonatal jaundice | 1 |

| Needed noninvasive respiratory support | 2 | ||

| Length of hospital stay | 2-8 days |

Table 2: Maternal and neonatal complications.

Twelve of the patients who were planned for VBAC did not go into spontaneous labor and had elective CS since the prevailing practice in our hospital is not to offer induction of labor with prostaglandins in patients with a scarred uterus.

A total of 48/55 that is 87% of our study patients were delivered by caesarean section (Table 1).

Table 3 shows the indications for caesarean sections (Table 3).

| Indication for caesarean section | Number of cases (n=55) |

|---|---|

| Did not go into labor till planned date of delivery | 12 |

| Declined VBAC | 15 |

| Uncontrolled Diabetes | 6 |

| Poor previous obstetric History | 2 |

| Pre labor rupture of membranes | 2 |

| Short inter pregnancy interval less than 18 months | 1 |

| Preeclampsia | 4 |

| Fetal distress | 1 |

| Failure to progress | 1 |

| Lower segment fibroid preventing vaginal delivery | 1 |

| Breech presentation at term | 1 |

| Intra uterine growth restriction | 1 |

Table 3: Indications for caesarean sections.

Discussion

In this prospective observational service evaluation study of 358 patients, we found a very high cesarean section rate of 87%. There are no similar studies which have looked into the cesarean section rate in patients with combined pregestational and gestational diabetes on treatment and previous one cesarean section, specifically. But there are listed studies which have looked into cesarean section rate and diabetes in pregnancy on treatment and without treatment.

A study by Goldman, et al. showed cesarean section rate of 35.3% in gestational diabetic patient as compared to 22% for non-diabetic patients [11,13]. Similarly Naylor, et al. found the cesarean section rate of 22% in non-gestational diabetic patient as compared to 30 and 34%, in gestational diabetes without treatment and gestational diabetes on treatment group [14,15].

Another study by Buchanan, et al. found a cesarean section rate of 43% in insulin treated gestational diabetes patients which were twice as high compared to patient on diet only [13,15].

A Canadian study by LAI FY IN 2005 found a cesarean section rate of 36.9% in gestational diabetic patients [15].

But all these studies referenced above have not specifically looked into the patients who had one previous cesarean section as compared to our study [11,13-15]. These studies also noted that recognition of gestational diabetes may lead to a lower threshold for cesarean delivery. In our study group of patients, the recognition of diabetes and previous delivery by cesarean put together may have led to a lower threshold for decision of cesarean delivery.

In this group of patients, especially in Qatar where there is significant diversity of population from different parts of world, no record of previous surgery, in some cases late or no antenatal care prior to delivery, patients choice of mode of delivery and hospital guidelines all may have contributed to this very high cesarean section rate.

On the contrary a study by Dominic Marchiano 2003 compared the success rate of attempted VBAC in gestational diabetic and nondiabetic patient and found VBAC rate of 70% in gestational diabetic patient which is almost similar in our study (67%) [16]. Similarly, Coleman et al. found VBAC rate of 64% for patient who attempted vaginal delivery in gestational diabetes group [4].

Recent study by Hadas Ganer Herman, et al. in 2017 also demonstrated that GDM significantly lowers the rate of TOLAC as compared to woman without GDM but does not diminishes likelihood of VBAC which is also seen in our study [17].

The perinatal outcome of our study shows a high complication rate among pre-gestational diabetic patients, which is similarly seen in the study done in Oman, which compared outcome of patient with gestational and pre-gestational diabetes by Abu-Heija et al. and his team [18]. In this study they found complications of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia were more in pre-gestational diabetic patients. The development of these additional complications may have contributed to early interventions and higher cesarean section rates (7/8 patients) in these patients.

The key strength of this study is that it is the first of its kind looking purely at patients with pregestational and gestational diabetes who required treatment and had one previous delivery by caesarean section. Our study is highlighting and supporting other published studies and raising the need to conduct other future prospective studies with bigger cohort in this higher risk group of diabetic pregnant women. We recommend that these future studies should ideally be multi-centered.

The main limitation of the present study is that, it is a noncomparative service evaluation which comes with its own inherent weak statistical data interpretation and bias.

Another limitation is the small number of cohort but this is due to the fact that our patients are of higher risk subset group of combined pregestational and gestational diabetes on pharmacotherapy.

Conclusion

We found an exceptionally high caesarean section rate of 87% in our study which is almost twice as high as was found in the general diabetic population from other studies. This may be due to multiple risk factors, key ones being diabetic on treatment and previous one caesarean section. Our study is the first of its kind to determine the Cesarean section rate and perinatal outcome in diabetic patients requiring medical treatment and with one prior cesarean section. Presence of additional risk factors may increase the risk for caesarean section and increase the risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcome. Therefore, there is need for multi-centered studies to determine the optimal cesarean section rate that affords the lowest perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality and also on how to modify these confounding factors so as to decrease the high caesarean section rate amongst this high risk group of patients. The sharing of these maternity indicators may be used for benchmarking and help reduce cesarean section rates and improve the neonatal and maternal outcomes.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and participant consent was not necessary as this study is an evaluation of our routine clinical practice and did not require any direct individual patient identifiable data

Consent for publication

Not applicable since this is a service evaluation

Authors' contributions

JR initiated the idea, wrote article, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript write up and revisions. VBdrafting and critical revision of article for important intellectual content and analysis for final approval. KA analysis and interpretation of data, write up and revision of manuscript. HS analysis and interpretation of data, write up and revision of manuscript. SJ data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, write up and revision of manuscript. TAE analysis and interpretation of data, write up and revision of manuscript. KD analysis and interpretation of data, write up and revision of manuscript. SB analysis and interpretation of data, write up and revision of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank Dr. Mohammad Daghash, for his clinical contribution and support at the Joint Diabetic Clinic.

References

- Okunoye G, Konje J, Lindow S, Perva S (2015) Gestational diabetes in the gulf region: Streamlining care to optimize outcome. J Local Glob Health Sci 2: 1-6.

- Al-Kuwari MG, Al-Kubaisi BS (2011) Prevalence and predictors of gestational diabetes in Qatar. Diabetol Croat 40: 65-70.

- Gorgal R, Gonçalves E, Barros M, Namora G, Magalhaes A, et al. (2012) Gestational diabetes mellitus: A risk factor for non-elective caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 38: 154-159.

- Coleman TL, Randall H, Graves W, Lindsay M (2001) Vaginal birth after cesarean among women with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184: 1104-1107.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins (2018) ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 131: e49-e64.

- Molina G, Weiser TG, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe-Leitz T, et al. (2015) Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA 314: 2263-2270.

- RCOG (2017) External cephalic version and reducing the incidence of term breech presentation (Green-top Guideline No. 20a).

- Tempest N, Navaratnam K, Hapangama DK (2015) Does advanced operative obstetrics still have a place in contemporary practice? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 27: 115-120.

- Ayres-De-Campos D, Cruz J, Medeiros-Borges C, Costa-Santos C, Vicente L (2015) Lowered national cesarean section rates after a concerted action. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 94: 391-398.

- Moses RG, Knights SJ, Lucas EM, Moses M, Russell KG, et al. (2000) Gestational diabetes: Is higher caesarean section rate inevitable? Diabetes Care 23: 15-17.

- Goldman M, Kitzmiller JL, Abrams B, Cowan RM, Laros RK (1991) Obstetric complications with GDM. Effects of maternal weight. Diabetes 40: 79-82.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2008) Diabetes in pregnancy: Management of diabetes and its complications from pre-conception to the postnatal period. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health, London.

- Buchanan TA, Kjos SL, Montoro MN, Wu PYK, Madrilejo NG, et al. (1994) Use of fetal ultrasound to select metabolic therapy for pregnancies complicated by mild gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 17: 275-283.

- Naylor CD, Sermer M, Chen E, Sykora K (1996) Caesarean delivery in relation to birth weight and gestational glucose tolerance: Pathophysiology or practice style? Toronto trihospital gestational diabetes investigators. JAMA 275: 1165-1170.

- Lai FY, Johnson JA, Dover D, Kaul P (2016) Outcomes of singleton and twin pregnancies complicated by preâ€existing diabetes and gestational diabetes: A populationâ€based study in Alberta, Canada, 2005-11. J Diabetes 8: 45-55.

- Marchiano D, Elkousy M, Stevens E, Peipert J, Macones G (2004) Diet-controlled gestational diabetes mellitus does not influence the success rates for vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190: 790-796.

- Herman HG, Kogan Z, Bar J, Kovo M (2017) Trial of labour after caesarean delivery for pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Gynecol Obstet 138: 84-88.

- Abu-Heija AT, Al-Bash M, Mathew M (2015) Gestational and pregestational diabetes mellitus in Omani women: Comparison of obstetric and perinatal outcomes. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 15: e496-e500.

Citation: Ramawat J, Boama V, Ashawesh K, Satti H, Jacob S, et al. (2019) Perinatal Outcome in Patients with Diabetes in Pregnancy and One Previous Caesarean Section: A Prospective Observational Service Evaluation. J Preg Child Health 6:404. DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000404

Copyright: © 2019 Ramawat J, et a. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4317

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Apr 04, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3511

- PDF downloads: 806