Research Article Open Access

Participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live.: Affective and Cognitive Outcomes for Children who Stutter

Courtney T. Byrd*, Elizabeth Hampton, Megann McGill and Zoi Gkalitsiou

The University of Texas, 1 University Station A1100, Austin, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Courtney T. Byrd

The University of Texas, University Station

Austin, Texas, USA

Tel: 512 232 9426

E-mail: Courtney.byrd@austin.utexas.edu

Received Date: April 11, 2016; Accepted Date: June 15, 2016; Published Date: June 24, 2016

Citation: Byrd C, Hampton E, McGill M, Gkalitsiou Z (2016) Participation in Camp Dream Speak Live: Affective and Cognitive Outcomes for Children who stutter. J Speech Pathol Ther 1:116. doi: 10.4172/2472-5005.1000116

Copyright: © 2016 Byrd CT, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Speech Pathology & Therapy

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to explore the influence of participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live., an intensive therapy program, on the communication attitudes, peer relationships and quality of life of children who stutter.

Method: Participants were 23 children who stutter (n=5 females; n=18 males; age range 4–14 years) who attended a weeklong intensive therapy program that was exclusively developed to address the affective and cognitive components of stuttering. Outcome measures included the KiddyCAT Communication Attitude Test for Preschool and Kindergarten Children who Stutter, the Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES), and the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pediatric Peer Relationships Form. Parents of children who participated in the program completed online parent proxy versions of the Kiddy-CAT, OASES, and PROMIS approximately one month after their child’s participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. concluded.

Results: Results suggest that participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. led to significant increases in the child’s communication attitude, the child’s perception of his/her ability to make friends, and also significantly reduced the impact of stuttering on the child’s overall quality of life. Additionally, parents of children who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. reported they observed positive increases in their child’s perception of his/her own ability to make friends as well as significant decreases in their child’s perspective of the impact of stuttering on his/her overall quality of life.

Conclusion: Results support the notion that significant improvements in communication attitude as well as significant reductions in the impact of stuttering on overall quality of life can be achieved in a short period of time.

Keywords

Stuttering; Communication attitudes; Resilience; Peer relationships; Intensive treatment

Background

Stuttering is a complex, multifactorial disorder characterized by atypical disruptions in the forward flow of speech. Among the (at least) 5% of young children who start to stutter, 70 to 80% will recover naturally (i.e., stop stuttering without formal treatment) [1] Prediction regarding whether a particular child will recover without intervention is not yet possible, but variables such as the child’s speech/language abilities and social/emotional development may impede natural recovery [2-4]. A relationship between these developmental characteristics and a child’s response to stuttering treatment has also been suggested [5] though no formal exploration has been completed. Additionally, similar to other multifactorial developmental speechlanguage impairments, such as autism and specific language impairment where individual differences predominate [6-8], parent understanding of child development, the nature of parent communicative interactions with their child, and parent engagement in therapy can significantly facilitate progress in treatment [8-10].

Given the diversity of parent and child considerations, a variety of treatment approaches have been developed for use with children who stutter. Some treatments focus on operant conditioning aimed at increasing fluency and decreasing stuttering through reinforcement and correction [11,12]. Other treatment methodologies focus on reducing stuttered speech while accounting for the experience of the family as a whole, the heterogeneity of stuttering, and the diversity of interactions between parents and their children [9,10,13-16]. Although speech fluency may prove to be comparably reduced regardless of whether an operant or a family-focused approach is used and reductions may occur more rapidly than natural recovery [17,18], any direct comparisons are premature as data to independently support either approach are lacking, particularly, with regard to the familyfocused approach. Nevertheless, if different approaches to stuttering therapy for children yield comparable reductions in stuttering frequency, as well as similar rates of treatment failure, these findings beg the question, why is treatment of any kind critical for young children who stutter?

The answer is simple yet not trivial, some children who stutter will persist in their stuttering whether or not they receive treatment of any kind. Persistent stuttering can lead to significant negative academic, emotional, social, and vocational consequences [19-23]. Thus, there is a strong need to explore treatment approaches for children who stutter that address the potential significance of persistent stuttering. The present study addresses this need by exploring the outcomes of Camp Dream. Speak. Live., an intensive therapy program for children who stutter that is specifically geared towards improving the child’s overall quality of life.

The vast majority of explorations of the effects of intensive treatment programs lasting five consecutive days for approximately 40 hours have focused on adults who stutter. Relatively few studies have examined the effects of intensive therapy for children who stutter. Among the limited investigations that have assessed treatment outcomes for weeklong (or shorter duration) intensive therapy programs for children who stutter, all have focused exclusively on speech fluency as a measure of progress [24,25]. To date, to the present authors’ knowledge, there have been no published outcomes specific to <1 week intensive therapy programs for children who stutter that are structured to address the affective and cognitive components of stuttering. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the influence of participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live., an intensive treatment program for which the goals are to (1) improve how children who stutter feel about their ability to communicate, (2) increase their positive perception of their ability to establish friendships, and (3) lessen the influence of stuttering on their overall quality of life.

Importance of improving positive communication attitudes

Research has demonstrated that children who stutter are uniquely vulnerable to negative peer to peer interactions, with a large majority at risk for bullying and teasing even in settings where there has been a funded effort to reduce these adverse exchanges [26]. It is often assumed that the overt behavior of stuttering is the trigger for the difference in interpersonal relationships, but it is possible that the child who stutters may display an attitude towards his/her speech that yields the peer perception of reduced social status. That possibility does not place the blame on the child who stutters, but it does offer a unique perspective from which to view the data on the relationship between bullying and stuttering. None of the previous studies have examined the communication attitudes of those children who reported being treated more negatively by their peers.

Perhaps, if the child perceives their ability to communicate more positively, he or she will no longer be a target, regardless as to whether the child continues to stutter or not. If the child who stutters feels positive about his or her communication skills, he or she would presumably be less likely to feel anxious in social settings and would also be more likely to feel positive about his or her ability to make friends. In fact, in the bullying literature, perceived difficulties in the ability to make friends and anxiety specific to social interactions are considered to either be consequences of bullying, or the precise factors that increase the likelihood of the child being a victim of bullying [27]. Camp Dream. Speak. Live. is designed to increase the child who stutters’ perception of his or her ability to make friends as well as reduce nervousness and anxiety in social settings.

Importance of increasing resiliency

Another target of Camp Dream. Speak. Live. is resilience. Resilience is defined as the person’s ability to successfully navigate adversity [28]. To prevent stuttering from negatively impacting their everyday life, persons who stutter need to be able to demonstrate stability when they sense they are about to experience a stutter and variability in the manner in which they address that unexpected moment of disfluency. The use of improvisation training is a key strategy to developing and strengthening resilience [29]. Through improvisation, children who stutter can learn that they cannot anticipate every possible exchange they will have but they will feel comfort with knowing that they can respond in a variety of ways, all of which can lead to a successful communicative exchange. Thus, these children will experience positive emotional responses specific to communication which will in turn increase their resilience.

Given that the relationship between resilience and positive emotional thinking is moderated by negative thoughts [30], Camp Dream. Speak. Live. also engages the child in group reflection of negative thinking and specifically targets increases in understanding of the value and use of positive self-talk. Researchers have suggested mindfulness training such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [31,32] as an effective approach for adults who stutter but it has not yet been explored with children who stutter. Allowing children who stutter to recognize their thoughts regarding their communication and to learn how to neutralize those thoughts is a critical component to Camp Dream. Speak. Live.

In addition to the value of being mindful of negative thinking, studies have also indicated that for children at risk for increased anxiety and low self-confidence, providing opportunities to engage in self-praise that are intended to replace the negative thought patterns they have already developed and/or to counter potential future negative thoughts that could develop over time is of significant benefit to their resilience [33,34]. Camp Dream. Speak. Live. addresses expression of these thoughts verbally as well as through art given that research shows that some children are better able to share difficult emotions through artistic outlets [35,36].

Importance of developing mentorship and leadership skills

Another fundamental aspect of Camp Dream. Speak. Live. is the value of helping oneself through helping others. There is a significant body of literature to suggest that the act of helping someone else cope with the same behavior for which you have struggled results in increased self-esteem, a deeper connection to the community who would be in need of your help, and also increases self-advocacy [37,38]. Through helping others, people are more likely to acquire a more profound understanding of their own challenges and how to best navigate similar challenges in the future. Thus, helping others also increases resilience. Camp Dream. Speak. Live. assigns participants to Pay it Forward peer networks wherein older children who stutter share advice for navigating life as person who stutters with the younger children in their group. Additionally, on each day of the program participants share what they learned from each other through their interactions in these networks and, together, each network provides specific suggestions for helping other people who stutter whom they have not yet met.

To that end, leadership skills are increased when people are provided with an opportunity to share their life lessons with others who may potentially encounter similar challenges. Leadership skills are also enhanced through the act of teaching others specific skills that the individual has found to be useful [39]. Every child who participates in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. is educated about the importance of leadership. The children learn what makes a good leader, acknowledge famous leaders and brainstorm ways to be everyday leaders. Each child reflects upon his or her own innate leadership skills and shares the ways in which they lead by example. The children also reflect upon their aspirations and the leadership roles they envision for themselves in the future. Throughout the duration of Camp Dream. Speak. Live. the children also visit with other “everyday” leaders who also happen to stutter to further their understanding of the many ways in which they can be leaders. In addition, each child selects their goals as leaders for each day of the program and reports on the ways in which they worked towards those goals.

An added benefit to consider with regard to the children being provided distinct opportunities to help and lead other persons who stutter is how the children who are being helped are inspired by their helper in a way that is unique because the helper is also a person who stutters. Research related to the influence of role models on perception of self and future achievement suggest positive effects particularly when the role model has navigated a comparable path whether it be race, gender, intellectual disability, etc. [40]. The more a person understands their own challenges and can see success reflected in others who have faced similar challenges, the more positively they will view their own potential.

Importance of peer to peer relationships

An additional fundamental focus of Camp Dream. Speak. Live. is the role of friendship in young children’s future social cognitive development and self-esteem. Children who experience friendships in preschool and early school age years are less likely to have difficulties with perceptions of self and also less likely to face social isolation [41]. For those children who have not experienced friendships, feelings of insecurity and social inhibition are more likely to develop [42]. Through participation in the variety of activities in Camp Dream. Speak. Live., the children are provided opportunities to bond with each other in meaningful and lasting ways. For example, research has shown that peer relationships in both children and adults are effectively fostered through dance [43]. Dancing facilitates the desire to connect with others [44,45] and with dancing there is no concern about speech fluency. Thus, dancing is a critical component to Camp Dream. Speak. Live.

In addition to dancing, art, written expression, small group discussion, and participation in open mic opportunities serve to establish authentic connections between the children. Across each one of these methods, the participants are encouraged to share personal journeys with others with each journey ending with advice for their peers specific to how they can manage the situation if they should ever face the same situation. This process of sharing individual experiences coupled with advice has been documented as a necessary step in the establishment of meaningful bonds. Celebration, laughter and fun is also a fundamental component to the establishment of genuine friendships, therefore, throughout the duration of Camp Dream. Speak. Live., children engage in activities designed to ignite joy and humor [46].

In summary, Camp Dream. Speak. Live. has been developed to address the affective and cognitive components of stuttering. The treatment protocol includes a variety of distinct opportunities designed to address these components. Specifically, the current study explored the following questions:

Does participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. improve the communication attitudes of children who stutter?

Does participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. increase the child who stutters’ positive perception of his/her ability to establish friendships?

Does participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. lessen the influence of stuttering on the child who stutters’ overall quality of life?

Methods

Participants

Approval for the completion of this study was provided by the first author’s university Institutional Review Board and written, informed consent and assent were obtained for each participant. Participants were 23 children who stutter (n=5 females; n=18 males) who attended Camp Dream. Speak. Live. at The University of Texas at Austin. Fourteen of the participants were between the ages of 7-14 years old and nine of the participants were between the ages of 4-6 years old. All participants had previously received a formal diagnosis of stuttering by a certified speech-language pathologist. Additionally, parents of all participants reported that their child presented with stuttering.

Stuttering severity was determined from an audio and video recorded, 5-minute conversational speech sample that was collected on the first day of the treatment program. Each participant’s conversation sample (N=300 words) was analyzed by trained research assistants using the Stuttering Severity Instrument–4 (Riley, 2009). The mean rating for all 23 participants who stutter was 26.81 (SD=11.67), with 2 participants receiving severity ratings of very mild, 7 participants receiving ratings of mild, 9 participants receiving ratings of moderate, 1 participant receiving a rating of severe, and 4 participants receiving ratings of very severe.

Procedures

Activities designed to improve communication and increase resiliency. Throughout each of the five days of Camp Dream. Speak. Live., the children engaged in communication exchanges of varied difficulty, with the guiding principle of speaking freely, rather than fluently (refer to Byrd & Hampton, 2016, for access to the treatment program manual). These exchanges included speaking in front of all of the participants in the program at least two times per day in order to share their thoughts specific to a designated topic, learning the fundamentals of improvisational communication, and engaging in a variety of extemporaneous speaking activities with select groups of peers in front of the entire cohort of participants. In addition, the children participated in a campus-wide open mic where they went to the most highly foot trafficked area of campus and took turns sharing about stuttering. The children also participated in campus-wide educational outreach by setting up a table on campus and engaging passersby with educational materials the children themselves have developed specific to stuttering. The children also had multiple opportunities to observe their peers who stutter engage in these communication situations and witnessed the acknowledgment and praise those children received for sharing their thoughts without any internal hesitation or external concern with regard to whether or not they might stutter. Additionally, the children participated in guided small and large group discussions regarding the freedom of speaking without internal and/or external judgment of the fluency of their message.

Acceptance of self and the ability to persevere across all communication situations despite challenges was also targeted through scheduling activities in a sequence that encouraged the children to become increasingly more comfortable with expressing themselves in a group. Through participation in an interactive magic show, breakdancing lessons, guided improve sessions, marching/singing in the “dreamer” parade, and, ultimately, performing in the talent show the children learned to accept and celebrate each other for their authenticity. The program culminated with a pep rally led by university cheerleaders and premier athletes where participants were inspired by the personal journeys shared by the university students and then led in motivational cheers intended to instill an overall sense of confidence, excitement and fun surrounding the entire treatment program experience.

Activities designed to facilitate mentorship and leadership. Participants had the opportunity to interact with role models that included both persons who stutter who have accepted their stuttering and do not allow speech fluency to dictate their life choices as well as persons who do not stutter who have overcome significant challenges to achieve their dreams. Participants were also assigned to Pay it Forward peer groups wherein they were instructed to share about their most challenging and rewarding experiences with their speech and impart advice for navigating life without allowing stuttering to significantly compromise their daily thoughts, feelings and actions. Within their Pay it Forward peer networks, the children were taught the qualities of a successful leader and shown how leading by example can change their own life as well as the lives of others around them for the better. Participants also engaged in creative action exercises where they envisioned their dreams and shared their plans for achieving those dreams. Leadership skills were further developed in the older participants (ages 11+ n=6) who were assigned the role of junior clinicians. On the first day of the program, junior clinicians met with the program director as a group and were empowered as role models and examples for the younger members of their Pay it Forward peer group. Junior clinicians assumed roles of lead emcee standing beside younger peers as they held the microphone, serving as spokespersons for Camp Dream. Speak. Live. When talking with visitors and members of the media who visited the program, and leading the open mics and advocacy events across campus. Given that adolescent and teen individuals who stutter present with increased negative thoughts and emotions related to stuttering [31], these opportunities placed adolescent campers in situations that directly combatted these feelings, and provided a sense of accomplishment and achievement. Finally, for every organized exchange across the duration of the program, there was a different participant who was awarded the role as emcee, which only serves to further enhance their leadership skills and their confidence in their communication abilities.

Over the five day period, participants realized that they are the experts regarding their own journey with stuttering and what works best for them. Participants who had previous long-term speech therapy for their stuttering shared their opinions about what was most effective versus what was least effective and why they think that might be. These participants also recorded the strategies that they previously learned and provided examples of those strategies in action to be used as instructional tools for future speech-language pathology students as well as other children who stutter. Additionally, participants created instructional videos in which they taught others what stuttering is and how people should interact with persons who stutter. Participants were also assigned to specific educational outreach groups and each group formally educated one of the visitors to Camp Dream. Speak. Live. regarding the nature and treatment of stuttering.

Activities designed to improve peer to peer relationships. Increasing participants’ confidence in their ability to make friends is another goal of Camp Dream. Speak. Live. To accomplish this goal, children engaged in structured activities specifically designed to facilitate bonding. For example, the children participated in team oriented activities such as glow bowling, complex designing and building of innovative crafts, as well as problem solving where the goal was to support the success of the team as a whole. Additionally, for at least two of the four daily open mic opportunities, the children were required to share the thoughts and feelings of their peer – a requirement that led to deeper, more meaningful understanding and respect for each other’s perspectives – a necessary step to establish positive peer relationships. An additional self-reflection and peer relationship building activity included art projects in which the participants illustrated their favorite memories from the weeklong program. Peers then wrote specific messages on each of their peer’s artwork – they were instructed to specify in their message what makes that particular person special. The participants then presented their final canvas to the rest of the program participants and were asked to share their most favorite memory and the qualities that their peers see in them. These posters were sent home with each child to serve as a visual reminder of their ability to make friends, the fact that they are not alone in their stuttering and the many different ways in which they are special.

Activities designed to promote understanding of bullying and teasing. Learning how to effectively navigate bullying and teasing is an additional fundamental focus of Camp Dream. Speak. Live. To address this goal, a motivational speaker partnered with a child friendly mascot engaged the children in a variety of games that were designed to be fun but also educational. Through their interactions with this speakermascot pair, the children were educated about what bullying and teasing is, how to identify when it is happening, and how to best address this type of situation. The children were also asked to brainstorm ways in which they can share about their own stuttering that feel empowering versus embarrassing. In addition, the children were encouraged to think of other children who stutter who were not able to attend this program and what message they would most like for those children to learn about stuttering. Similarly, the children were asked to think about children as well as adults who do not stutter and what they would most like for those persons to understand about stuttering. Once these messages were identified, the children videorecorded their messages and shared them with the program’s participants, with the persons in their immediate environment, and via the Lang Stuttering Institute’s social media to allow the child to have the chance to reach others who do and do not stutter with those messages that they felt were the most important.

Activities designed to desensitize child towards stuttering. The children who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. also learned specific strategies for acknowledging stuttering and decreasing discomfort towards stuttering. These strategies included self-disclosing in a non-apologetic manner and stuttering on purpose in a manner that is as close to their real stutter as possible. The children also shared about themselves and their speech in a pointedly positive manner. For example, instead of asking the child whether or not he or she loves their speech, the children were prompted to complete sentences such as, “I love my speech because…” and “I am special because…” The children recorded these messages with the intent of sharing these videos which, in turn, reinforces encouraging and affirming perspectives of the speech and the speaker who stutters regardless of the fluency of their message. In addition, at the end of each day participants were provided with a “Wow of the Day” document written by their clinicians that described a moment in which the child excelled with regard to his or her communication attitude, peer to peer interaction, and leadership. A photograph was included to serve as reminder of each day and participants were asked to reflect and share about this moment with their families.

Outcome measures

Assessment tools used to measure outcomes for participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. included child and parent report.

Child report: Child participants age 4 to 6 years old were administered the KiddyCAT Communication Attitude Test for Preschool and Kindergarten Children who Stutter. Children age 7 to 14 years old completed the Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering. The KiddyCAT was read to the younger cohort of participants, in accordance with the test administration guidelines, by a research assistant who had completed fluency training with the first author. Children completing the OASES forms were asked to do so independently. All children completed the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pediatric Peer Relationships – Short Form 8a Participants completed each of these surveys related to their perceptions towards their speech and toward their relationships with peers one day prior to participation in the program. To collect post-data, all participants completed the same set of self-report measures immediately following participation in the intensive treatment program [47-51].

Parent report: Parents of children who participated in the program were provided a link to an online questionnaire approximately one month after their child’s participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. concluded. The surveys were parent proxy forms of the Kiddy-CAT and the OASES. Parent surveys differed dependent upon the age of the child participant (i.e., 4-6 years old, 7+ years old) (Appendix A).

Results

Communication attitudes

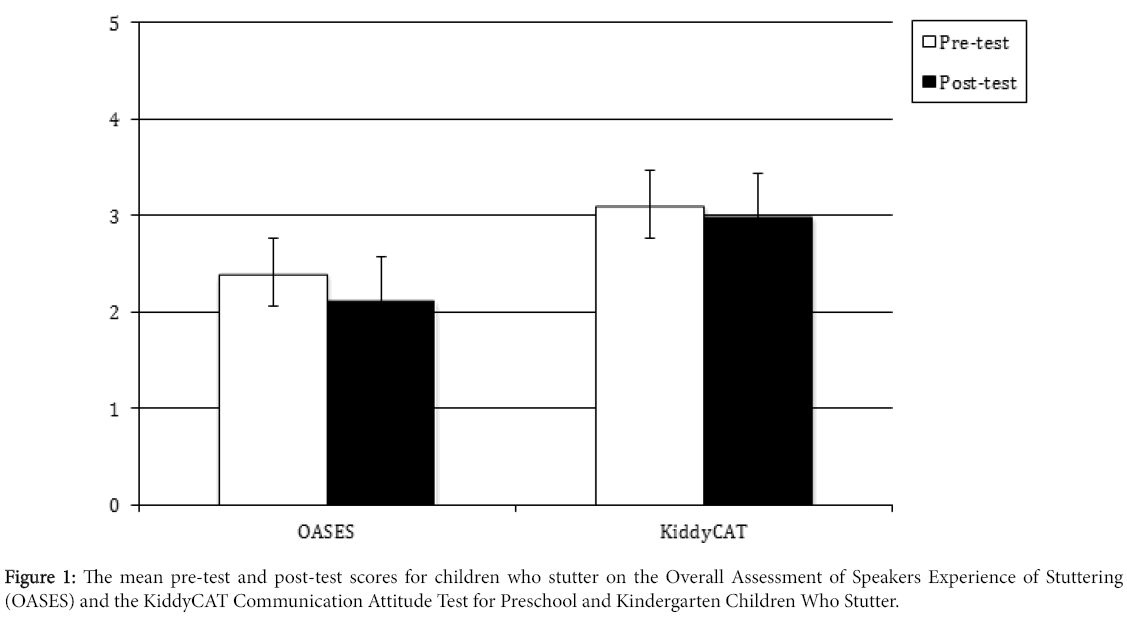

For children 4 to 6 years of age, the average pre-test KiddyCAT score was 3.11 (range=0-7). The average post-test KiddyCAT score was 3.00 (range=0-7). As illustrated in Figure 1, KiddyCAT pre-test and post-test scores were not found to be significantly different using a paired t-test analysis t(8)=0.160, p =0 .877.

For children age 7 to 14 years old, the average pre-test OASES score was 2.41 (range=1.33-4.71), which corresponds to a moderate impact of stuttering on daily life. The average post-test OASES score was 2.13 (range=1.13-4.3), which corresponds to a mild-moderate impact of stuttering on daily life. As seen in Figure 1, OASES pre-test and posttest scores were found to be significantly different using a paired t-test analysis t(13)=4.230, p<0.001. That is, children who stutter who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. demonstrated a significant decrease in the impact that stuttering has on their lives at the end of the week as compared to the day prior to the first day of their participation in the intensive program.

Decomposition of the overall OASES scores using paired t-test analyses of the individual sections revealed a significant difference between pre- and post-data for Section 4: Quality of Life t(13)=2.881, p=0.013. No additional significant pre- and post-data differences were noted for Section 1: General Information t(13)=2.102, p=0.056, Section 2: Your Reactions to Stuttering t(13)=2.060, p=0.060, or Section 3: Communication in Daily Situations t(13)=1.715, p=0.110.

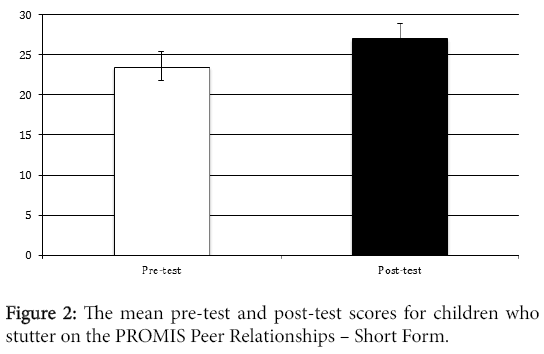

Peer relationships

When comparing pre-test and post-test PROMIS Peer Relationship scores for the whole group (N=23), the average pre-test score was 23.53 and the average post-test score was 27.07, yielding a difference of 3.54 points. This observed difference was found to be statistically significant using a paired samples t-test t(22)=3.497, p<0.002. As shown in Figure 2, children who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. demonstrated a significant increase in their social health, including social function and sociability, across peer-to-peer relationships from the beginning to the end of the their participation in the program.

Parent perspectives

Parents of child participants age 4-6 years old. Eight of the nine (88.89%) parents of children age 4-6 years old fully completed and submitted the online survey. The following results are descriptions of the eight parents’ responses to the questionnaire (Appendix A).

Parents reported that their children’s participation “very positively” (37.5%), “positively” (50%), or “neither positively or negatively” (12.5%) influenced their children’s feelings of acceptance by other children. Parents also reported that participating in the program “very positively” (25%), “positively” (50%), or “neither negatively or positively” (25%) affected their children’s feelings of how much they can count on friends. Additionally, parents reported that participation impacted their children’s feelings that they are able to talk to their friends about anything “very positively” (50%), “positively” (37.5%), or “neither negatively or positively” (12.5%). Parents also reported that their child’s participation “very positively” (62.5%), “positively” (25%), or “neither negatively or positively” (12.5%) influenced their children’s perceptions of their abilities to make friends. Furthermore, parents reported that their children’s perception of whether other children wanted to be friends with them were affected “very positively” (50%), “positively” (37.5%), or “neither negatively or positively” (12.5%) by their children’s participation. Half of parents reported that their children’s perception that other children want to talk with them was “very positively” impacted by their children’s participation, while the other half of parents reported their children were “positively” influenced by their participation. Parents also reported that participating “very positively” (37.5%) or “positively” (62.5%) affected their children’s perceptions that other children want to be around them. Parents reported that their feelings about their children’s acceptance by other children was “very positively” (25%), “positively” (62.5%), or “neither negatively or positively” (12.5%) impacted by their children’s participation (Table 1).

| Participation in the intensive therapy program influenced | Very positively | Positively | Neither positively or negatively | Negatively | Very negatively |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My child’s feelings of acceptance by other children his or her age. | 37.50% | 50% | 12.50% | 0% | 0% |

| My child’s feelings of how much he or she can count on friends. | 25% | 50% | 25% | 0% | 0% |

| My child’s feelings he or she is able to talk to friends about anything. | 50% | 37.50% | 12.50% | 0% | 0% |

| My child’s perception of his or her ability to make friends. | 62.50% | 25% | 12.50% | 0% | 0% |

| My child’s perception that other children want to be his or her friend. | 50% | 37.50% | 12.50% | 0% | 0% |

| My child’s perception that other children want to talk to him or her. | 50% | 50% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| My child’s perception that other children want to be around him or her. | 37.50% | 62.50% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| My feelings about my child’s acceptance by other children my child’s age. | 25% | 62.50% | 12.50% | 0% | 0% |

Table 1: Online survey responses provided by parents of child participants age 4-6 years old.

Parents of child participants age 7-14 years old. Eight of the 14 (57.14%) parents of children ages 7-14 years old completed and submitted the online questionnaire (Appendix A). The following results are descriptions of the eight parents’ responses to the questionnaire.

Quality of life

Parents reported that their children’s participation in the intensive therapy program reviewed in the present study “very positively” (50% of responses) or “positively” (50% of responses) influenced their children’s perception of how their lives are impacted by the fact that they stutter. Parents also reported that participation in the program “very positively” (63% of responses) or “positively” (13% of responses) affected how their children’s lives are impacted by how other people react to their stuttering. Additionally, 63% of parents reported that their child’s participation “very positively” impacted how much stuttering gets in the way of their child’s ability to succeed in school and how much stuttering gets in their way to do the things they want to do. Seventy-five percent of parents reported that their children’s participation “very positively” affected how much stuttering gets in the way of their children’s ability to speak to their parents. Overwhelmingly, parents reported that participation “very positively” (83%) or “positively” (17%) affected how their children’s lives are impacted by the fact that they stutter. In response to the questionnaire, parents responded that participation “very positively” (33%), “positively” (50%) or “neither negatively or positively” (17%) impacted how other people react to their children’s stuttering. Additionally, parents reported that their children’s participation “very positively” (50%) or “positively” (50%) influenced how much stuttering gets in the way of their children’s abilities to succeed in school. Parents also reported that participation “very positively” (67%), “positively” (17%), or “neither negatively or positively” (17%) impacted how much stuttering gets in the way of their children’s abilities to do the things their children want to do. Parents also reported that their children’s participation “very positively” (67%) or “positively” (33%) affected how much stuttering gets in the way of their children’s abilities to talk to them. Additionally, parents reported that participation “very positively” (50%) or “neither negatively or positively” (50%) influenced how much stuttering gets in the way of their child’s ability to participate in social events. Parents also reported that their children’s participation “very positively” (67%), “positively” (17%), or “neither negatively or positively” (17%) impacted how much stuttering gets in the way of their children’s abilities to have a good life (Table 2).

| Participation in the intensive therapy program influenced my child’s perception.. | Very positively | Positively | Neither positively or negatively | Negatively | Very negatively |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Of how his or her life is impacted by the fact that he or she stutters. | 83% | 17% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how his or her life is impacted by how other people react to his or her stuttering. | 50% | 13% | 38% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her ability to succeed in school. | 63% | 25% | 0% | 13% | 0% |

| Of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her ability to do the things he or she wants to do. | 63% | 13% | 13% | 13% | 0% |

| Of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her ability to talk to you. | 75% | 13% | 13% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her ability to talk to friends. | 63% | 13% | 25% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her ability to participate in social events (like sports teams, parties, sleepovers, etc.) | 50% | 25% | 25% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her self-confidence. | 75% | 25% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how he or she is accepted by other children his or her age. | 71% | 29% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how he or she feels about being able to talk to his/her friends about anything. | 43% | 43% | 14% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how he or she feels that he/she can count on his/her friends. | 57% | 29% | 14% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how his/her perception of his/her ability to make friends. | 57% | 29% | 14% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how he/she perceives that other children want to talk to and be friends with him/her. | 57% | 43% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her ability to have a good life. | 63% | 13% | 25% | 0% | 0% |

Table 2: Online survey responses provided by parents of child participants age 7-14 years old.

Peer to peer relationships

As shown in Table 2, parents also reported that their children’s participation “very positively” (63% of responses) or “positively” (13% of responses) influenced their children’s perceptions of how much stuttering gets in the way of his or her ability to speak with his or her friends. Additionally, parents reported that their children’s participation “very positively” (75% of responses) or “positively” (25% of responses) impacted their children’s perception of how much stuttering gets in the way of their self-confidence. Additionally, parents reported that participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. “very positively” (71% of responses) or “positively” (29% of responses) affected their children’s feelings of acceptance by other children their age. According to parents, participation “very positively” (57%) or “positively” (29%) impacted how much their children feel that they can count on their friends. Furthermore, parents reported that participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. “very positively” (43%) or “positively” (43%) influenced their children’s feelings about being able to talk to their friends about anything. Fifty-seven percent of parents reported that participation “very positively” affected their children’s perceptions of their ability to make friends, and an additional 29% rated participation in the program as “positively” impacting the children. Parents also reported that participating in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. “very positively” (57%) or “positively” (43%) influenced their children’s perceptions that other children want to be their friends and that other children want to talk to them.

Discussion

To review, the purpose of the present study is to explore the treatment outcomes for Camp Dream. Speak. Live. an intensive five day program for children who stutter. In contrast to most intensive treatment programs, Camp Dream. Speak. Live. was exclusively developed to address the affective and cognitive components of stuttering. Results suggest that participation in this program leads to significant increases in the child’s communication attitude, the child’s perception of his/her ability to make friends, and also reduces the impact of stuttering on the child’s overall quality of life. Additionally, parents of children who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. reported that they also observed positive increases in their child’s perception of his/her own ability to make friends as well as significant decreases in their child’s perspective of the impact of stuttering on his/her overall quality of life.

Communication attitudes

Children ages 4 to 6 years old who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. did not demonstrate an upward shift post participation likely because they entered the program with a positive communication attitude. Yet, these findings are still of significant importance as they suggest that even though stuttering is addressed directly and discussed significantly over the course of the program, such discussion did not compromise any of these children’s positive feelings towards their communication skills. This is an important finding particularly for parents who may be concerned that increasing a child’s awareness of stuttering may unintentionally lead to the child developing concern [52].

In contrast to the younger children, the children who were 7 years of age and older who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. showed a significant increase in their communication attitude. These children entered into the program with more negative perspectives towards their communication abilities. The marked shift toward a more positive communication attitude demonstrates that the activities the children completed during Camp Dream. Speak. Live. directly influenced their perspectives regarding their communication abilities. It is difficult to determine if there is any one activity that potentially contributed more significantly to these outcomes than another, or, if perhaps, a combination of all of the activities lead to this change. Future research should explore potential combined and/or independent effects.

Impact of stuttering on child’s overall quality of life: Although, at present, it is difficult to determine whether one activity may be of more benefit than another, the follow up analysis of the significant increase in the attitudinal assessment of those children 7 to 14 was largely driven by increases in the quality of life section of the OASES. Thus, the activities completed seem to distinctly influence changes in this particular area of measurement on this tool. Additionally, the parents of the children who participated in the program unanimously reported that their child’s participation influenced their child’s life in a positive manner and also reported that their participation reduced the impact of stuttering on their child’s overall quality of life. The question remains as to whether or not these positive results can be maintained over time. Future research should explore the longitudinal implications of participation in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. Given that the program targets resilience, in addition to the OASES, other assessment tools that more directly assess any change in the client’s resiliency should be included in future studies.

Peer relationships: All of the children who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. demonstrated a significant increase in their perspectives of their abilities to interact with peers and make friends. This finding is of particular importance as the results included those children age 4 to 6 as well as children 7 and older. Thus, even the younger children whose communication attitudes were positive prior to the program still received meaningful benefit. Furthermore, the perception of a significant increase in effective peer-to-peer relationship skills was not only reported by the children, but was also reported by the children’s parents. Although the parents did not attend or observe their children as they were completing the program, they still reported a positive increase in their child’s social interactions. All parents shared that their child’s participation in the program notably increased their child’s perception of his/her ability to make friends in their everyday life apart from the treatment program environment.

Research suggests that it is unclear whether children are targeted by bullies because they feel socially inept or if children feel socially inept as a result of being bullied [27]. Thus, the improvement in perspectives with regard to the ability to socialize successfully can potentially lessen the future likelihood of the children who participate in this intensive program being bullied. Additionally, given the data to suggest children who experience meaningful bonds at a young age are less likely to face social isolation at a later age, the children who participated in Camp Dream. Speak. Live. may be less likely to experience feelings of loneliness and separation from peers. Additionally, the opportunity to support the other participants in a mentorship role as well as their daily leadership assignment serves to make the children see themselves as valuable partners to their peers. Future research should follow these children throughout their elementary years to determine if, in fact, there is link between participation in this program and likelihood being bullied and/or feeling socially isolated later in life.

Additional considerations: The results from the present study are preliminary in nature and may be compromised, by, at least, a few factors. First, the measurements employed in the present study may not be sensitive enough to yield meaningful findings. Specifically, for the children age 4 to 6, the use of the Kiddy CAT as the singular measurement of attitude may have compromised the possibility of detecting any changes in the child’s attitude over time. Past therapy experiences were not controlled for in the present study. Additionally, other important considerations such as stuttering severity, time since onset of stuttering, and temperament were not included in the outcome analyses. Future research should determine whether previous therapy moderates treatment outcomes. The data are not longitudinal in nature; thus, the changes noted could potentially be temporary. Finally, as is typical of survey data, not all parents completed the posttreatment surveys. Had we requested that the parent complete the survey in person, we would have likely had completed surveys from all parents, but it was important for the parents to complete these surveys anonymously. Future research should investigate ways to ensure confidentiality while simultaneously securing response from all parents.

Conclusion

To date, to these authors’ knowledge there have been no published data to support intensive treatment programs that target communication attitudes and the impact of stuttering on the child who stutters’ overall quality of life. The program reviewed in the present study, Camp Dream. Speak. Live., targeted these critical aspects and demonstrated that significant improvements in communication attitude as well as significant reductions in the impact of stuttering on overall quality of life can be achieved in a short period of time. Although these preliminary results are promising, additional research is needed to determine if there are specific aspects of the program that may be more beneficial than others. Additionally, longitudinal data are needed to determine if the differences observed are maintained over time.

References

- Yairi E, Ambrose N (2005) Early childhood stuttering. Austin: Pro-Ed Inc.

- Choi D, Conture EG, Walden TA, Lambert WE, Tumanova V (2013) Behavioral inhibition and childhood stuttering.J Fluency Disord 38: 171-183.

- Spencer C, Weber-Fox C2 (2014) Preschool speech articulation and nonword repetition abilities may help predict eventual recovery or persistence of stuttering.J Fluency Disord 41: 32-46

- Walden TA, Frankel CB, Buhr AP, Johnson KN, Conture EG, et al. (2012) Dual diathesis-stressor model of emotional and linguistic contributions to developmental stuttering.J Abnorm Child Psychol 40: 633-644.

- Richels C, Conture E (2007) Early intervention for stuttering: An indirect method. In E. Conture& R. Curlee (Edn) Stuttering and other fluency disorders (3rd. Ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Thieme Medical

- Leonard C, Eckert M, Given B, Berninger V, Eden G (2006) Individual differences in anatomy predict reading and oral language impairments in children. Brain 129: 3329-3342

- Siller M, Swanson M, Gerber A, Hutman T, SigmanM (2014) A parent-mediated intervention that targets responsive parental behaviors increases attachment behaviors in children with ASD: Results from a randomized clinical trial. J Autism DevDisord. 44: 1720-1732.

- Millard SK, EdwardsS, Cook FM (2009) Parent-child interaction therapy: Adding to the evidence. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 11: 61-76.

- Starkweather CW, Gottwald S,Halfond M (1990) Stuttering prevention: A clinical method. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Yaruss SJ, Coleman C,Hammer D (2006) Treating preschool children who stutter: Description and preliminary evaluation of a family-focused treatment approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 37: 118-136.

- O'Brian S, Iverach L, Jones M, Onslow M, Packman A, Menzies R (2013). Effectiveness of the Lidcombe Program for early stuttering in Australian community clinics. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 15: 593-603.

- Onslow M1, Andrews C, Lincoln M (1994) A control/experimental trial of an operant treatment for early stuttering.J Speech Hear Res 37: 1244-1259.

- Hill D (2003) Differential treatment of stuttering in the early stages of development. In H.H. Gregory, J. H. Campbell, C.B. Gregory, & D.G. Hill (Eds.). Stuttering therapy: Rationale and procedures Boston: Allyn& Bacon

- Millard SK, Nicholas A, Cook FM (2008) Is parent-child interaction therapy effective in reducing stuttering?J Speech Lang Hear Res 51: 636-650.

- Richels C, Conture E (2011) Diagnostic data as predictor of treatment outcome with young children who stutter. In B. Guitar and R. McCauley (Eds.) Treatment of stuttering: Conventional and controversial interventions. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Rustin L, Botterill W, Kelman E (1996) Assessment and therapy for young dysfluent children: Family interaction. London: Whurr.

- Franken MC1, Kielstra-Van der Schalk CJ, Boelens H (2005) Experimental treatment of early stuttering: a preliminary study.J Fluency Disord 30: 189-199.

- de Sonneville-Koedoot C, Stolk E, Rietveld T, Franken MC (2015) Direct versus Indirect Treatment for Preschool Children who Stutter: The RESTART Randomized Trial.PLoS One 10: e0133758

- Craig A1, Blumgart E, Tran Y (2009) The impact of stuttering on the quality of life in adults who stutter.J Fluency Disord 34: 61-71.

- Ezrati-Vinacour R1, Platzky R, Yairi E (2001) The young child's awareness of stuttering-like disfluency.J Speech Lang Hear Res 44: 368-380.

- Langevin M, Kleitman S, Packman A, Onslow M (2009) The peer attitudes toward children who stutter (PATCS) scale: an evaluation of validity, reliability, and the negativity of attitudes. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 44: 352-368.

- Langevin M, Kully D, Teshima S, Hagler P, Prasad NGN (2010) Five-year longitudinal treatment outcomes of the ISTAR Comprehensive Stuttering Program. Journal of Fluency Disorders 35: 123-140.

- Yaruss JS1, Quesal RW (2004) Stuttering and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: an update.J CommunDisord 37: 35-52.

- Druce T, DebneyS, Burt T (1997) Evaluation of an intensive treatment program for stuttering in young children. Journal of Fluency Disorders 22: 169-186.

- McCarthy M, Fisher J, & Block S (1994) Outcome and predictors of outcome in children undergoing an intensive smooth speech program for stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders 19: 193

- Davis S, Howell P, Cooke F (2002)Sociodynamic relationships between children who stutter and their non-stuttering classmates. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 43: 939-947.

- Marini ZA, Dane AV, Bosacki SL, YLC-CURA (2006) Direct and indirect bully- victims: Differential psychosocial risk factors associated with adolescents involved in bullying and victimization. Aggressive Behavior 32: 551- 569.

- Connor KM, Davidson JRT (2003) Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety 18: 76-82.

- Rankin, A., Dahlbäck, N., & Lundberg, J. (2013). A case study of factor influencing role improvisation in crisis response teams. Cognition, Technology, & Work, 15, 79- 93.

- Rosenberg, A. (2016). Foster resilience in adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Oncology Times, 38, 8-9.

- Beilby, J.M., Byrnes, M.L., &Yaruss, S,J. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy for adults who stutter: psychosocial adjustment and speech fluency. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 37, 289-299.

- Boyle MP1 (2011) Mindfulness training in stuttering therapy: a tutorial for speech-language pathologists.J Fluency Disord 36: 122-129.

- Menzies RG, Onslow M, Packman A, O'Brian S (2009) Cognitive behavior therapy for adults who stutter: a tutorial for speech-language pathologists.J Fluency Disord 34: 187-200.

- Delany, C., Miller, K.J., El-Ansary, D., Remedios, L., Hosseini, A., &McCleod, S. (2015). Replacing stressful challenges with positive coping strategies: A resilience program for clinical placement learning. Advances in Health Science Education (20), 1301-1324.

- Brown, E. D., & Sax, K. L. (2013). Arts enrichment and preschool emotions for low- income children at risk. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 337–346.

- Gantt, L., &Tinnin, L. (2009). Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(3), 148–153.

- Anderson S1, Bigby C1 (2015) Self-Advocacy as a Means to Positive Identities for People with Intellectual Disability: 'We Just Help Them, Be Them Really'.J Appl Res Intellect Disabil .

- Hiedemann G, Cederbaum JA, Martinez S, Lebel TP (2016) Wounded healers: How formerly incarcerated women help themselves by helping others. Punishment & Society 18: 3-26.

- Martinek T, Schilling T (2003) Developing compassionate leadership in underserved youths. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 74: 33-39.

- Egalite AJ, Kisida B, Winters MA (2015) Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement. Economics of Education Review 45: 44-52.

- Laursen B, Bukowski WM, Aunola K, Nurmi JE (2007) Friendship moderates prospective associations between social isolation and adjustment problems in young children. Child Dev. 78: 1395-1404.

- LairdR.Laird, RD, Jordan KY, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE (2001) Peer rejection in childhood, involvement with antisocial peers in early adolescence, and the development of externalizing behavior problems. Development and psychopathology 13: 337-354.

- American Dance Therapy Association (2009) About dance/movement therapy. Retrieved March, 9, 2013.

- Baudino L. (2010) Autism spectrum disorder: A case of misdiagnosis. American Journal of Dance Therapy 32: 113-129.

- Deveraux C (2012) Moving into relationships. In L. Gallo-Lopez & L.C. Rubin (Eds.), Play-based interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. New York: Boutledge.

- Pottie C, Sumarah J (2004) Friendships between persons with and without developmental disabilities. Ment Retard 42: 55-66.

- Rile G (2009) Stuttering severity instrument for children and adults. 4th edn Tigard OR: CC Publications.

- Byrd C, Hampton E (2016) Camp Dream. Speak. Live: An Intensive Therapy Program for Children who Stutter. UT Copy Services: Austin, TX.

- Vanryckeghem M, Brutten G (2007) The KiddyCAT: A communication attitude test for preschool and kindergarten children who stutter. San Diego CA: Plural PublishingInc

- Yaruss JS, Coleman CE, Quesal RW (2010) OASES: Overall assessment of the speaker’s experience with stuttering. McKinney TX: Stuttering Therapy Resources, Inc.

- DeWalt DA, Thissen D, Stucky BD, Langer MM, Morgan DeWitt E et al.(2013). PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships Scale: Development of a Peer Relationships Item Bank as Part of Social Health Measurement. Health Psychology 30: 1-21.

- Zebrowski PM, Schum RL (1993) Counseling parents of children who stutter. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology 2: 65-73.

Relevant Topics

- Stuttering therapy

- Active listening

- Aphasia

- Articulation disorders:

- Autism Speech Therapy

- Bilingual Speech pathology

- Clinical Linguistics

- Communicate Speech pathology

- Interventional Speech Therapy

- Late talkers

- Medical Speech pathology

- Spectrum Pathology

- Speech and Language Disorders

- Speech and Language pathology

- Speech Impediment / speech disorder

- Speech pathology

- Speech Therapy

- Speech Therapy Exercise

- Speech Therapy for Adults

- Speech Therapy for Children

- Speech Therapy Materials

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13052

- [From(publication date):

October-2016 - Jul 15, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12012

- PDF downloads : 1040