Parkinson's Disease Blood Test for Primary Care

Received: 16-Jun-2022 / Manuscript No. JADP-22-67578 / Editor assigned: 20-Jun-2022 / PreQC No. JADP-22-67578 (PQ) / Reviewed: 07-Jul-2022 / QC No. JADP-22-67578 / Revised: 14-Jul-2022 / Manuscript No. JADP-22-67578 (R) / Published Date: 22-Jul-2022

Abstract

Background: A blood-test that could serve as a potential first step in a multi-tiered neurodiagnostic process for ruling out Parkinson’s disease (PD) in primary care settings would be of tremendous value. This study therefore sought to conduct a large-scale cross-validation of our Parkinson’s disease Blood Test (PDBT) for use in primary care settings.

Methods: Serum samples were analyzed from 846 PD and 2291 volunteer controls. Proteomic assays were run on a multiplex biomarker assay platform using Electrochemiluminescence (ECL). Diagnostic accuracy statistics were generated using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), Sensitivity (SN), Specificity (SP) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV).

Results: In the training set, the PDBT reached an AUC of 0.98 when distinguishing PD cases from controls with a SN of 0.84 and SP of 0.98. When applied to the test set, the PDBT yielded an AUC of 0.96, SN of 0.79 and SP of 0.97. The PDBT obtained a negative predictive value of 99% for a 2% base rate.

Conclusion: The PDBT was highly successful in discriminating PD patients from control cases and has great potential for providing primary care providers with a rapid, scalable and cost-effective tool for screening out PD.

Keywords

Serum; Parkinson’s disease; Primary care; Screening tool; Blood test

Abbrevations

Abbreviations A2M: α2 Macroglobulin; AD: Alzheimer’s Disease; AUC: Area Under the Curve; B2M: Beta 2 Microglobulin; COU: Context of Use; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; DATATOP: Deprenyl And Tocopherol Antioxidative Therapy of Parkinsonism; DaT-SPECT: Dopamine Transporter Single Photon Emission CT; ECL: Electrochemiluminescence; ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay; Factor VII: Factor 7; FABP: Fatty Acid Binding Protein; GPs: General Practitioners; IVD: In vitro Diagnostic; ITR: Institute for Translational Research; ICAM-1: Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1; IL: Interleukin; LBD: Lewy Body Dementia; NPV: Negative Predictive Value; NDRD: Neurodegenerative Disease Blood Test Reference Database; PPY: Pancreatic Polypeptide; PD: Parkinson’s Disease; PDBT: Parkinson’s Disease Blood Test; ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristic; SN: Sensitivity; SAA: Serum Amyloid A; SAMD: Software as a Medical Device; SP: Specificity; SVM: Support Vector Machine; TARC: Thymus and Activation-Regulated Chemokine; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha; VCAM 1: Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease affecting over 1% of individuals over the age of 65 in the United States [1]. The cost of PD to our society was reported to be $23 billion annually in the U.S. in 2005 [2]. Given the rapidly growing segment of the elderly population, these costs will continue to increase over the next several decades. The most accurate diagnosis of PD comes from specialty clinics where clinical assessments and advanced neurodiagnostic procedures are costly, time-consuming, and invasive. In the United States, primary care clinics serve as the “gatekeeper” to specialty clinics and these frontline primary care practitioners provide the referrals for advanced diagnostic procedures. However, the average duration of primary care visits is around 18 minutes making detailed neurological examinations difficult [3]

In 2017, Plouvier and colleagues interviewed community-dwelling PD patients and general practitioners (GPs) to understand their thoughts on the role of primary care in PD management. These authors found discrepancies between patients’ and GP views as patients felt that GPs lacked expert knowledge or skills and diminished the role of GPs in patients at advanced PD stages. GPs, on the other hand, valued patient autonomy in early-stage decision making but in more advanced PD stages felt a more active role of the GP is warranted. The authors stated that patients would likely benefit from the more holistic approach brought by the GP if done in conjunction with specialty care [4].

Currently, however, there are no rapid or cost-effective tools for primary care providers to use in daily practice to screen patients with possible PD symptoms. Within primary care settings, the purpose of screening tests is to rule out patients who do not require additional medical procedures or diagnostic follow-up, thereby resulting in stress reduction and cost containment.

Our team has proposed a multi-tiered neurodiagnostic process for neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) [5-7].

Over the last several decades, the search for biomarkers that have diagnostic and prognostic utility in neurodegenerative diseases has grown exponentially with the majority of work focusing on neuroimaging and cerebrospinal (CSF) methodologies. In fact, the dopamine transporter single photon emission CT [DaT-SPECT] has been approved as a tool for diagnosing PD. Research suggests that CSF markers may also hold utility in the differential diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases [8-15]. While advanced neuroimaging and CSF methods have tremendous potential as biomarkers of PD, invasiveness, accessibility and cost barriers preclude these from being utilized as an initial step in detection procedures. Therefore, it has been proposed that blood-based biomarker methods may serve as the optimal first step in a multi-tier detection process [17,18] and requires additional investigation, similar to their application in the field of oncology [16-21]. Our team has conducted a series of studies demonstrating the utility of blood-based biomarkers for detecting PD as well as discriminating PD from other neurodegenerative diseases [22]. Here we completed a large-scale cross-validation of our PD Blood Test (PDBT) for use in primary care settings.

Materials and Methods

Participants and reference database

Parkinson’s disease data: Our team recently completed baseline and longitudinal assays on serum samples from the previously conducted DATATOP trial. DATATOP methods regarding participant recruitment, study design, enrollment, consent procedures, and funding sources have all been previously published. Briefly, DATATOP was a multi-site placebo- controlled clinical trial designed to test the impact of deprenyl 10 mg/d and/or tocopherol (vitamin E) 2000 IU/d on PD progression (in combination with levodopa) [23]. A total of 656 baseline PD serum samples had requisite data in our database, and were used in the current study. An additional n=190 serum samples from PD cases were already included in our research database from PD specialty evaluations. Therefore, there was a total number of n=846 PD cases. No cases included in this study had a diagnosis of PDdementia.

Neurodegenerative Disease Blood Test Reference Database (NDRD): Complex diseases, such as neurodegenerative diseases, require that multiple factors (or biological pathways) be considered when making a diagnosis rather than just a single factor. In our prior work, we have generated a blood test for detecting AD specifically for use in primary care settings [5,22,24-26]. This blood test was discovered and validated on the premise that taking multiple biomarkers into account would yield a more accurate approach than any single marker [22,25,26]. This multimarker approach has led to multiple in vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests being advanced to clinical use in the field of oncology. However, in order advance such an “algorithm” to the clinic it requires an appropriate Reference Database that, in practice, when combined with the algorithm itself would be covered under FDA regulations as Software as a Medical Device (SAMD) [24-27].

Therefore, our team generated and published a NDRD. The NDRD contains data from n>5000 participants across a broad range of diseases (e.g., AD, PD, DLB, controls) and blood fractions (serum and plasma). Only completely de-identified data are included in the NDRD. To be included in the NDRD, the data came from studies that

1. Conducted comprehensive cognitive assessments on all participants for accurate diagnosis and

2. Conducted under IRB approval and written informed consent was obtained.

Controls: Controls in the database had no neurodegenerative disease diagnosis, performed within normal cognitive parameters on neuropsychological testing and reported no decline in activities of daily living. For the purpose this study, control samples from serum data were utilized (controls n=2,291).

Proteomics

All serum samples were assayed in the University of North Texas Health Science Center Institute for Translational Research (ITR) Biomarker Core. The ITR Biomarker Core utilizes the Hamilton Robotics Easy Blood for blood processing, aliquoting, and realiquoting. A custom Hamilton Robotics StarPlus system was utilized for the preparation of all plates. Proteomic assays were run on a multiplex biomarker assay platform using electrochemiluminescence (ECL) per our previously published methods using commercially available kits [28]. ECL technology uses labels that emit light when electronically stimulated, which improves the sensitivity of detection for many analytes even at very low concentrations. ECL measures have well established properties for being more sensitive and requiring less volume than conventional ELISAs, the gold standard for most assays. We recently reported the analytic performance of several proteins for n>1,300 samples across multiple cohorts and diagnoses (normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, and AD) [22]. The assays are reliable and in our experience with these assays show excellent spiked recovery, dilution linearity, coefficients of variation, as well as detection limits. Inter and intra-assay variability has been excellent. Internal QC protocols are implemented in addition to manufacturing protocols including assaying consistent controls across batches and assay of pooled standards across lots. A total of 500 μl of serum was utilized to assay (singlicate) the following markers: Fatty Acid Binding Protein (FABP)-3, beta 2 microglobulin (B2M), Pancreatic Polypeptide (PPY), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), ICAM-1, thrombopoietin, α2 Macroglobulin (A2M), exotaxin 3, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF- α), tenascin C, interleukin (IL)-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-18, I-309, Factor 7 (Factor VII), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (VCAM 1), TARC and serum amyloid a (SAA). Our lab has run n>20,000 of these assays over the last several years with all CVs being <10% with the majority being <=6%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the R (V3.3.3) statistical software, SPSS 24 (IBM), and SAS. Support Vector Machine (SVM) analyses were conducted to discriminate PD cases from controls. SVM is based on the concept of decision planes that define decision boundaries and is primarily a classifier method that performs classification tasks by constructing hyperplanes in a multidimensional space that separates cases of different class labels.

Diagnostic accuracy was calculated via Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. The sample was randomly split (70/30) into training and test samples with diagnostic accuracy derived from the test sample. Finally, to provide estimates of the overall utility of the PDBT in ruling out PD in primary care settings, negative predictive values (NPVs; the probability that subjects with a negative screening test truly do not have disease) were calculated using a range of base rates including 2%, 5%, 10% and 15%.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the sample are provided in Table 1. The average age of the sample 63.8 (SD=13.4). The PD group was younger, more likely to be male, and reported higher levels of education (p-values<0.001) as compared to the normal control group.

|

PD | Normal control | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | ||

| N | 846 | 2291 | |

| Age | 59.5(12.6) | 65.4(13.4) | 4.16E-29 |

| Education | 13.76(4.65) | 12.74(6.62) | 1.59E-06 |

| Gender (%M) | 62.8 | 40.1 | 5.65E-30 |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the cohort.

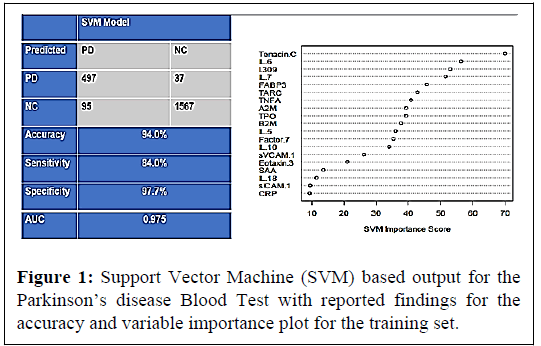

In the training sample, there were a total 592 PD samples and 1604 control samples. The SVM was applied with a 5-fold internal crossvalidation within the training sample for initial analysis and internal validation. The PDBT yielded an AUC of 0.98 with a SN of 0.84 and SP of 0.98 within the training set. The overall classification accuracy (correct and incorrect) along with the diagnostic accuracy statistics and variable importance plot in Figure 1.

Next the PDBT was directly applied to the test sample, which consisted of n=254 PD cases and n=687 controls. The PDBT yielded an AUC of 0.964 with a SN of 0.79 and SP of 0.97. The classification accuracy (correct and incorrect) as well as the ROC curve shows in Figure 2.

Finally, to provide a sense of how the PDBT would perform as a screening tool for ruling out PD in primary care settings, the NPV was calculated for a range of base rates. With a 2% base rate, the NPV was 0.99. Therefore, the physician is 99% accurate in ruling out PD with a negative blood test. The NPV for 5%, 10% and 15% base rates were 99%, 98% and 96%, respectively. If a physician used a 5% base rate for those adults complaining of new onset motor changes, and saw 5000 patients, the PDBT would rule out 4,660 patients from needing any additional testing procedures. There would be only 53 false negative cases.

Discussion

The current data provide additional support for the utility of the PDBT in primary care settings. In the current study, data were pooled for an aggregate sample of 846 PD samples and 2,291 control samples. Overall, the accuracy of the PDBT is excellent (i.e., >98%) for ruling out disease. As we have previously published, the goal of a screening test in primary care settings for neurodegenerative diseases is to rule out the disease [10,29], which is consistent with the use and performance of the vast majority of screening tests used in primary care settings on a daily basis [29].

In addition to detecting PD, our team has conducted a series of studies examining the possibility of a PDBT in discriminating PD from other neurodegenerative diseases. In an initial study, we analyzed our proteomic profile from 349 patients (150 AD, 49 PD, and 150 controls) and found that our serum-based PDBT-proteomic profile was >98% accurate in discriminating PD from AD. In the next study, we examined a plasma proteomic profile from 145 patients (32 PD, 57 DLB, 56 controls) from the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and Movement Disorders Clinic. The bloodbased proteomic profile was highly accurate in detecting neurodegenerative disease yielding an AUC of 0.94 versus controls, in discriminating PD from DLB with an AUC of 0.84, as well as discriminating AD/DLB from non-demented PD (AUC of 0.98) [7]. Next, we conducted a study in the Harvard Biomarker Study Bio repository by assaying n=150 plasma samples (PD n=50, “other neurodegenerative disease” n=50 [AD n=12, FTD n=25, other n=13], control n=50). The proteomic profile approach was highly accurate in discriminating PD from other neurodegenerative diseases with an AUC of 0.98. Therefore, this prior work suggests that our approach cannot only detect PD, but that it can also discriminate PD from other neurodegenerative diseases. The latter would be of value to primary care practitioners to know the appropriate referral for a given patient as well as for general neurology clinics when receiving referrals to determine the most appropriate clinician to receive the new patient.

There are limitations to the current study. First, it is possible that additional proteomic markers, not examined in this study, will increase the overall accuracy of the PDBT. AD specific markers such as Amyloid Beta (Aβ) 40, Aβ 40, tau and neurofilament light chain (NfL) have been increasingly explored both in blood and CSF for their utility in detecting AD and PD as well as distinguishing between neurodegenerative conditions [29–35]. Karikari and colleagues examined phosphorylated tau 181 (ptau181) and found that this one marker alone reached an AUC of 0.81 in distinguishing AD from PD [36]. In addition to AD specific biomarkers, PD specific biomarkers such as a-synuclein have also shown promise particularly when applied to distinguishing PD from other related conditions such as DLB [30,37]. While increased accuracy is not needed for the current screening Context of Use (COU), increased accuracy would be needed for the generation of a blood-based diagnostic test and therefore the addition of other such markers should be considered in future work. Second, it is possible that novel or known genetic markers will improve the diagnostic accuracy. It is of importance to note that the COU for the PDBT is not diagnostic, but rather as a screening tool to rule out PD within primary care settings. It will be important for this work to be replicated to ensure reproducibility.

Conclusion

The availability of the PDBT for primary care holds tremendous benefit. First, this is a rapidly scalable technology that can be implemented globally as a Laboratory Developed Test (LDT). The PDBT would provide primary care providers with actionable and objective information that is supported by several studies and many patients. Additionally, it is thought that the earlier therapeutics can be administered, the more beneficial they are to patients. The availability of the PDBT in primary care settings would provide a tool for rapid referrals. Finally, for clinical trials, the PDBT would provide a means of drastically expanding access to screening procedures well beyond specialty clinics. Overall, our series of studies, in combination with the current results, strongly support the utility of the PDBT for the COU of screening out PD in primary care settings.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research award #14448. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AG058537 and R01AG054073.

R01AG054073, and U01NS082148. Data and biospecimens used in preparation of this manuscript were also obtained from the Parkinson’s disease Biomarkers Program (PDBP) Consortium, supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health. Investigators include: Roger Albin, Roy Alcalay, Alberto Ascherio, Thomas Beach, Sarah Berman, Bradley Boeve, F. DuBois Bowman, Shu Chen, Alice Chen-Plotkin, William Dauer, Ted Dawson, Paula Desplats, Richard Dewey, Ray Dorsey, Jori Fleisher, Kirk Frey, Douglas Galasko, James Galvin, Dwight German, Steven Gunzler, Lawrence Honig, Xuemei Huang, David Irwin, Kejal Kantarci, Anumantha Kanthasamy, Daniel Kaufer, Qingzhong Kong, James Leverenz, Carol Lippa, Irene Litvan, Oscar Lopez, Jian Ma, Lara Mangravite, Karen Marder, Laurie Orzelius, Vladislav Petyuk, Judith Potashkin, Liana Rosenthal, Rachel Saunders-Pullman, Clemens Scherzer, Michael Schwarzschild, Tanya Simuni, Andrew Singleton, David Standaert, Debby Tsuang, David Vaillancourt, David Walt, Andrew West, Cyrus Zabetian, and Jing Zhang. The PDBP Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

SEO holds multiple patents in precision medicine for neurodegenerative diseases and is founding scientist in Cx Precision Medicine. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Tysnes OB, Storstein A (2017) Epidemiology of parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm 124: 901-5.

- Huse DM, Schulman K, Orsini L, Castelli‐Haley J, Kennedy S, et al., (2005) Burden of illness in parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 20: 1449-54.

- Shaw MK, Davis SA, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR (2014) The duration of office visits in the United States, 1993 to 2010. Am J Manag Care. 20: 820-6.

- Plouvier AO, Olde Hartman TC, Verhulst CE, Bloem BR, Van Weel C, et al., (2017) Parkinson’s disease: patient and general practitioner perspectives on the role of primary care. Fam Pract. 34: 227-233.

- O'Bryant SE, Edwards M, Johnson L, Hall J, Villarreal AE, et al., (2016) A blood screening test for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 3: 83-90.

- O'Bryant SE, Edwards M, Zhang F, Johnson LA, Hall J, et al., (2019) Potential two-step proteomic signature for parkinson's disease: Pilot analysis in the Harvard Biomarkers Study. Alzheimers Dement 11: 374-382.

- O'Bryant SE, Ferman TJ, Zhang F, Hall J, Pedraza O, et al., (2019) A proteomic signature for dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Dement 11: 270-276.

- Thal LJ, Kantarci K, Reiman EM, Klunk WE, Weiner MW, et al., (2006) The role of biomarkers in clinical trials for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20.

- Davies P, Resnick J, Resnick B, Gilman S, Growdon JH, et al., (1998) Consensus report of the working group on: “Molecular and biochemical markers of Alzheimer’s disease.” Neurobiol Aging 2: 109–116.

- O'Bryant SE, Mielke MM, Rissman RA, Lista S, Vanderstichele H, et al., (2017) Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: Current state of the science and a novel collaborative paradigm for advancing from discovery to clinic. Alzheimers Dement 13: 45-58.

- Graff-Radford J, Boeve BF, Pedraza O, Ferman TJ, Przybelski S, et al., (2012) Imaging and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor response in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain 135: 2470-2477.

- Colloby SJ, Firbank MJ, Pakrasi S, Lloyd JJ, Driver I, et al., (2008) A comparison of 99mTc-exametazime and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT imaging in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Int Psychogeriatr 20: 1124-1140.

- McKeith I, O'Brien J, Walker Z, Tatsch K, Booij J, et al., (2007) Sensitivity and specificity of dopamine transporter imaging with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies: A phase III, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 6: 305-313.

- Park E, Hwang YM, Lee CN, Kim S, Oh SY, et al., (2014) Differential diagnosis of patients with inconclusive parkinsonian features using [18F] FP-CIT PET/CT. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48: 106-113.

- Kaerst L, Kuhlmann A, Wedekind D, Stoeck K, Lange P, et al., (2014) Using cerebrospinal fluid marker profiles in clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 38(1):63-73.

- Henchcliffe C, Dodel R, Beal MF (2011) Biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease and Dementia with Lewy bodies. Prog Neurobiol 95: 601–613.

- Schneider P, Hampel H, Buerger K (2009) Biological marker candidates of alzheimer’s disease in blood, plasma, and serum. CNS Neurosci Ther 15: 358–374.

- Eller M, Williams DR (2011) α-Synuclein in Parkinson disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Clin Chem Lab Med 49: 403–408.

- Shtilbans A, Henchcliffe C (2012) Biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease: An update. Curr Opin Neurol 25: 460–465.

- Henriksen K, O’Bryant SE, Hampel H, Trojanowski JQ, Montine TJ, et al. (2014) The future of blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10: 115–131.

- Gold LS, Klein G, Carr L, Kessler L, Sullivan SD (2012) The emergence of diagnostic imaging technologies in breast cancer: Discovery, regulatory approval, reimbursement, and adoption in clinical guidelines. Cancer Imaging 12: 13–24.

- O’Bryant SE, Xiao G, Zhang F, Edwards M, German DC, et al. (2014) Validation of a serum screen for Alzheimer’s disease across assay platforms, species, and tissues. J Alzheimer's Dis 42: 1325–1335.

- No authors listed (1989) Datatop: A multicenter controlled clinical trial in early parkinson’s disease: Parkinson study group. Arch Neurol 46: 1052–1060.

- O’Bryant SE, Lista S, Rissman RA, Edwards M, Zhang F, et al. (2016) Comparing biological markers of Alzheimer’s disease across blood fraction and platforms: Comparing apples to oranges. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 3: 27–34.

- O’Bryant SE, Xiao G, Barber R, Reisch J, Doody R, et al. (2010) A serum protein-based algorithm for the detection of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 67: 1077–1081.

- Software as a Medical Device (SAMD): Clinical Evaluation - Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff (2017).

- O’Bryant SE, Gupta V, Henriksen K, Edwards M, Jeromin A, et al. (2015) Guidelines for the standardization of preanalytic variables for blood-based biomarker studies in Alzheimer’s disease research. Alzheimers Dement 11: 549–560.

- Hampel H, O’Bryant SE, Castrillo JI, Ritchie C, Rojkova K, et al. (2016) PRECISION MEDICINE – The Golden Gate for Detection, Treatment and Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 3: 243–259.

- Parnetti L, Gaetani L, Eusebi P, Paciotti S, Hansson O, et al. (2019) CSF and blood biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol 18: 573–586.

- Hansson O. (2021) Biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Medicine 27:954–963.

- Gaetani L, Blennow K, Calabresi P, di Filippo M, Parnetti L, et al. (2019) Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 90: 870–881.

- Lin CH, Li CH, Yang KC, Lin FJ, Wu CC, et al. (2019) Blood NfL: A biomarker for disease severity and progression in Parkinson disease. Neurol 93: e1104–e1111.

- Mollenhauer B, Dakna M, Kruse N, Galasko D, Foroud T, et al. (2020) Validation of Serum Neurofilament Light Chain as a Biomarker of Parkinson’s Disease Progression. Mov Disord 35: 1999–2008.

- Chojdak-Łukasiewicz J, Małodobra-Mazur M, Zimny A, Noga L, Paradowski B (2020) Plasma tau protein and Aβ42 level as markers of cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Adv Clin Exp Med 29: 115–121.

- Chang CW, Yang SY, Yang CC, Chang CW, Wu YR (2020) Plasma and Serum Alpha-Synuclein as a Biomarker of Diagnosis in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurol 10: 1388.

- Karikari TK, Pascoal TA, Ashton NJ, Janelidze S, Benedet AL, et al. (2020) Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: a diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. Lancet Neurol 19: 422–433.

- Ganguly U, Singh S, Pal S, Prasad S, Agrawal BK, et al. (2021) Alpha-Synuclein as a Biomarker of Parkinson’s Disease: Good, but Not Good Enough. Front Aging Neurosci 13: 702639.

Citation: O’Bryant SE, Petersen M, Zhang F, Johnson L, German D, et al. (2022) Parkinson’s Disease Blood Test for Primary Care. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 12: 545.

Copyright: © 2022 O’Bryant SE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2335

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Apr 26, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1947

- PDF downloads: 388