Parent-Child Connectedness as Predictor of Risky Sexual Behaviour among Adolescents in the Assin South District, Ghana

Received: 11-Sep-2022 / Manuscript No. jcalb-22-74266 / Editor assigned: 13-Sep-2022 / PreQC No. jcalb-22-74266 (PQ) / Reviewed: 27-Sep-2022 / QC No. jcalb-22-74266 / Revised: 29-Sep-2022 / Manuscript No. jcalb-22-74266 (R) / Published Date: 06-Oct-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000467

Abstract

Background: Lack of connectedness between adolescents and their parents has been found to affect adolescent development and decision-making negatively. This study investigates the specific elements of parentchild connectedness (PCC) that influence closeness in a relationship using Assin South District as a case study.

Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive design was employed with 354 respondents which comprised parents aged 30-59 years and older adolescents aged 15-19 years. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics, Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence and binary logistic regression.

Results:The study revealed that, a climate of trust, communication, structure of home and time shared constitute important elements of PCC that support closeness in a relationship. It was also emerged in the study that parents’ own awareness on sex education was the main predictor for sexuality communication with adolescents. The study discovered that some of the adolescents had ever had a date and also practised risky sexual behaviour.

Conclusion: Based on this, the study recommends that parents provide adolescents with the requisite information aimed at reducing any harmful consequences of behaviour when occurs to the adolescents. Also,parents in the Assin South district should endeavour to encourage their children to talk openly with them (parents) about their ideas, needs, and worries for redress.

Keywords

Child discipline; Climate of trust; Communication; Monitoring; Parent-child connectedness; Risky sexual behaviour; Structure; Time shared

Introduction

As kids, we come into the world without knowing how to cater for ourselves [1]. For survival, we rely solely on our parents for everything such as food, emotional warmth and protection [2]. Parents’ control on infants, from babyhood to adolescence, is much more significant than any other influence (Minnesota Student Survey Interagency Team, 2010). Studies that focus on adolescents’ sexual decision-making attitudes display that parents have a potent control on health outcomes for their children [3,4].

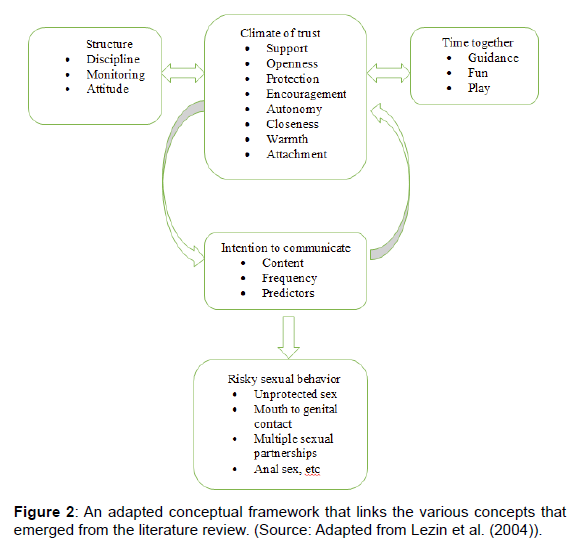

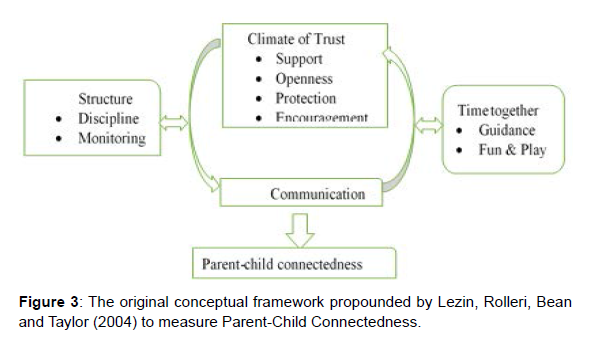

According to Lezin et al. (2004), parents, as part of their basic roles, endeavour to foster and provide a climate of trust which includes physical support, openness, protection, warmth, attachment and encouragement; communication which allows for the exchange of feelings and ideas among parents and children; an appropriate structure of home which attempts to syndicate discipline, monitoring, and guidance which leads to independence; and lastly, time shared together which also curtails meaningful interaction, guidance, support with laughter, play and fun. The above roles performed by parents were endorsed by Lezin et al. (2004) as the key elements of parent-child connectedness (PCC).

Notwithstanding, adolescents encounter aggregate hitches during their passage to maturity [5]. Many of these challenges could prevail throughout their lifetime [6]. The reason for this problem might be attributable to the information gap about sexually related matters. Therefore, risky sexual behaviour such as multiple sexual partnerships, unprotected sex, mouth-to-genital contact, anal sex, exposure to sexual acts at a younger age and transactional sex are common among adolescents [3,5,7]. These behaviours predispose them to multiple catastrophes of sexually transmitted infections including HIV and AIDS, unintended teenage pregnancy and unsafe abortions [8-10].

Nevertheless, there is accelerative indication that the roles that adults play matter a lot in the lives of adolescents. Studies from the developed world [11,12] and sub-Saharan Africa have endorsed adults to be paramount sex educators.

Connectedness is regarded as a basic human need that guarantees a sense of belonging and prevents the feeling of social alienation and solitude [13]. Lack of connectedness between adolescents and their parents has been found to affect adolescent development and decisionmaking negatively [13]. In Western societies, the value of the family unit for adolescents can be shaded by the tendency to see adolescence as an important developmental stage into adulthood which involves increased independence and decision-making responsibilities [14,15].

The family as a unit sustains its importance since it equips children with a sense of identity, physical support, social and emotional development [16,17]. Being attached and feeling loved and wanted is central to adolescents’ well-being and identity development [18,13].

In parent-child connectedness (PCC), parents help to convey information, sexual values, beliefs and expectations to adolescents in order to influence their attitudes towards risky sexual behaviour [19,20]. This connectedness, therefore, empowers adolescents to pull off the many problems connected with adolescence. There is an indication that when PCC is established, maintained and increased in a family, the outcome is a permanent bond among parent and the children based on mutual respect, love, trust and affection [3]. These are exhibited in daily interactions and uttered loosely as both parents and children migrate through their relationship together [21,22].

Parental talks on risky sexual related matters and adolescents’ decision-making can possibly stick only when the state of connection among parents and children is high [23,24]. This ‘stickiness’, according to Jerman and Constantine (2010), adds up to the effective role that PCC plays in delaying and reducing adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. Moreover, when PCC is high among parents and children, the climate that is created seems to be friendlier with less conflict [19]. This climate helps parents and adolescents to get along well in the family.

On the other hand, in families that PCC is low, the climate that is created is unpleasant coupled with misunderstanding and violence. An unsettled dispute is high in such a family [14,15]. Sharing of thoughts, feelings, sympathy, and regard are devoid of the family. Instead of attachment there is detachment in that family. Many negative consequences might happen in the forms of attachment to bad friends, risky sexual behaviours and difficulties forming one’s own intimate connection later in life.

Importantly, the news about adolescent sexuality in the world is better. Teen pregnancy is down and it has been declining steadily. Adolescents are delaying having sex today than a few years ago [25,26]. However, putting these judgements in perspective, there is little reason to believe that the ideal situation has been achieved. This is because at the international level, it has been estimated that about 21 million adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 years become pregnant while 2 million adolescent girls aged less than 15 years become pregnant in developing regions every year [27,28]. In addition to the above, about 3.9 million unsafe abortions among adolescent girls aged 15–19 years happen each year, adding up to the maternal mortality, morbidity and long lasting health issues. More so, maternal mortality risks are high among adolescent girls less than 15 years. In most developing countries, pregnancy complications and childbirth are the major causes of death among adolescent girls.

Again, adolescents worldwide have been seen to have the highest prevalence rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV and AIDS since the majority of them engage in sexual intercourse without any protection. Though these adolescents have enough messages on STIs including HIV and AIDS from different areas yet, they fail to put this information into practice for a change in their behaviours [29]. Most cases of STIs including HIV and AIDS, together with unintended pregnancies, observed in high communities are all indicators of the happenings on the ground [30]. Recent health menaces for adolescents are mostly behavioural rather than biomedical and more of these contemporary adolescents are engaged in risky sexual behaviour with potential hazardous effects [31].

Currently, sub-Saharan Africa is recognised as the area with high prevalence rates of teenage births. For instance, in 2018, birth rates among teenager’s amounted to over 100 births per 1000 girls aged 15-19 compared to lower rates in other countries in the world. For instance, United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], (2015) stated that most studies in the sub-region have as well documented ever-increasing sexual immoralities among teens. This is because teenagers often encounter tremendous pressure to indulge in sex, particularly from bad friends, exposure to unaccredited adult videos and the tendency for economic benefits (United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], 2015; WHO, 2020). This, consequently, leads a reasonable number of teenagers to engage in risky sexual behaviours at early stages of their lives [32,33].

These teens need appropriate guidance and attention to enable them to reduce such risky sexual behaviours (UNICEF, 2019). According to UNICEF (2019), the Central African Republic, Niger, Chad, Angola and Mali have high teenage birth rates above 178 per 1000. Furthermore, between 2010 and 2015, more than 45 per cent of women ranging between the ages of 20 and 24 years reported that they had their first babies by age 18.

In Ghana, teens aged 10-19 years and are with high sexual activity represent 23 per cent of the entire population [34]. Exposure to sexual activities starts early and this trend has multiplied in magnitude over the past decades. The 2014 GDHS reported that, the proportion of adolescent girls aged 15-19 years who had had their first sexual encounter by age 15 has increased by 61.6 per cent in a 15 year interval; from 7.3 per cent in 1998 to 11.8 per cent in 2014. On the other hand, the sexual debut by 18 years old adolescents has also declined from 56.7 per cent to 43.3 per cent for the 20-24 years old age group for the same period.

The median age of first sexual activity for the 20-24-year age group has remained relatively unchanged from 1998 to 2014 at around 18 years for women and about 19.5 for men. Risky sexual practices are prevalent among adolescents. This is exemplified by continuous multiple sexual partners, concurrent partners, and non-use of condoms by those who are sexually active (GDHS, 2014). Despite this, condom usage at first sexual encounter is 25.9 per cent among females aged 15-19-years old and 31.4 per cent for males [35]. The prevalence rate of teenage pregnancy for adolescents aged 15-19 years is 14 per cent of all pregnancies in Ghana [36]. This has become a national social vice in Ghana due to the increasing number of teenagers indulging in premarital sex.

In the Central Region, adolescent pregnancy rate is comparatively high than in some regions in Ghana [37]. As postulated by the Population Council, UNFPA and UNICEF (2016), the proportion of adolescent girls who had begun childbearing in the Central Region decreased from 33.3 per cent in 1993, which was the highest, to 18.7 per cent (the lowest in Central Region from 1993-2014) in 1998. However, it increased to 24.1 per cent in 2003 and thereafter, declined to 23.2 per cent in 2008 and further declined to 21.3 per cent in 2014. Despite the decrease in adolescent fertility in 2014, child births to females less than 20 years remain high in the region, indicating an early engagement in sexual activity, leading to early pregnancy.

The importance of the well-being of teenagers in any society is based on the fact that teenagers constitute a major source of potential human resource which, when given the necessary guidance to grow into adulthood, will shape the socioeconomic future of a country. Adolescent pregnancy in a country could weaken the development of that potential [38]. Reducing adolescents’ birthrate and attending to the many factors underlying it are essential for improving sexual and reproductive health and the socioeconomic well-being of teens [39]. According to Edilberto and Mengjia (2013), there is evidence that supports that immediate action should be taken to protect the rights of adolescents most especially, adolescent girls and also, to guarantee their education, health needs as well as to eradicate the risks of violence and pregnancy among these girls who are below 18 years. In essence, PCC has surfaced in many studies recently as a powerful superprotector in a family life that may buffer teens from the many problems they encounter in today’s world. As evidence accumulates about PCC being a super-protector for the reduction of many health and social problems (example, drug abuse, violence, risky sexual behaviour and unplanned pregnancy), there is currently a paucity of data regarding which elements of PCC influence closeness in a relationship and aid the super protective role that PCC plays and, therefore, must be promoted.

PCC emphasises a climate of trust, structure, communication and time shared as key elements [1] which, when observed, the outcome is an everlasting bond between parents and their children [40]. In Ghana, the elements of PCC have not been well explored, so, it becomes difficult to predict specific elements of PCC that are considered to be important, influence closeness in a relationship and aid the effective role that PCC plays in delaying and reducing risky sexual behaviour among adolescents. A search from libraries and electronic databases has disclosed that little research has been done on PCC. The few research available was all limited in scope, coverage and assessment. For instance, Adu-Mireku (2003) only examined family communication about HIV and AIDS, Kumi-Kyereme, Awusabo-Asare, Biddlecom and Tanle (2007) studied sexual communication by characterizing persons who have talked about sex-related matters with the adolescent while Manu, Mba, Asare, Odoi-Agyarko and Asante (2015) explored sexual communication by targeting both parents and children.

It should be noted that none of the aims drawn in the above studies is about the parent-child connectedness and risky sexual behaviour among adolescents. Moreover, to the best of my knowledge, no study in Ghana as well as Assin South District has empirically sought to examine the four key elements of PCC let alone, to document those that are considered to be important, support closeness in a relationship and aid the effective role that PCC plays in delaying and reducing risky sexual behaviour among adolescents. Given this, the research article attempts to investigate parent-child connectedness and risky sexual behaviour among adolescents in the Assin South District by specifically assessing if the kind of climate of trust parents build and maintain with children predicts risky sexual behaviour among adolescents in the Assin South District, ascertaining how parents’ intention to engage children in communication influences risky sexual behaviour among adolescents in the Assin South District, determining whether the kind of structure parents build with children influences adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour in the Assin South District, analysing whether the time parents and children share together predicts risky sexual behaviour among adolescents in the Assin South District; and lastly document the specific elements of PCC that are considered to influence closeness in a relationship. This paper hypothesised that parent-child connectedness is not related to adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour.

Theoretical perspective

This article employed the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) which guided the researchers to explain how parent-child connectedness (PCC) influences behaviour. The Theory of Reasoned Action is based on several related constructs and hypotheses proposed by social psychologists to understand and to predict human behaviour [41]. TRA came up from the long-standing cooperative studies done by famed psychologists [42]. This happened from attitude studies using the Expectancy Value Models [43]. The renowned psychologists did this formulation of TRA after trying to figure the disagreement that existed between attitude and behaviour. From the start of TRA in behavioural studies, it has been used to study a broad variety of issues and is now recognized as one of the most powerful theories about volitional human behaviour [44]. It is founded on the premise that human beings unremarkably act sensibly, as the name of the theory implies; that is, they take account of accessible information and consider the implications of their actions. The theory contends that a person’s intention to carry out or not to carry out behaviour is the proximate determinant of that action; without unanticipated events, people are predicted to act in conformity with their intentions. Intention to postpone and cut down risky sexual behaviour in the Assin South District can also be noted to reckon on the adolescents’ voluntary behaviour. Adolescents in Assin South District might take account of the available message about risky sexual behaviour and think about the outcomes of delaying and reducing or not delaying and reducing. The message well thought out by the adolescents might be the adverse effects, how silent others will think about them, commitment required to be able to delay and reduce risky sexual behaviour.

The stronger the intention to delay and reduce risky sexual behaviour, the more the adolescents in the Assin South District are supposed to try to delay and reduce risky sexual behaviour, and therefore, the greater the expectation that the behaviour will, in reality, be acted upon. Thus, the basic interest is with characterizing the constituents underlying the formation and change of behavioural intent [45]. An adolescent in Assin South District’s intention to act in a definite way may be influenced by their ‘attitude’ about the behaviour understudied and their perception of the societal forces on them to act in that manner, that is, ‘subjective norms’. The relative contribution of attitudes and normative belief varies per the behavioural circumstance and the person concerned. Attitudes are predicted by the beliefs about the results of undertaken the behaviour and the assessment of these anticipated results. The subjective norm depends upon the beliefs about how different people feel the adolescent in the Assin South District should act and their motivation to abide by these expectations from the different people. Most of the adolescents in the Assin South District who engage in risky sexual behaviour might hold fast to normative norms in that they might assess the behaviour before they perform it. As a result of this, any behaviour they engage in might think about how such behaviour will influence their peers. They might also consider how positively or negatively their behaviour will shackle other community members. That is the basic rationale why this paper is based on TRA.

Understanding the kind of relationship PCC attempts to capture

Of course, as identified in any human relationship, an enduring mutual fulfilling connection between parents and children can take various diverse ways and is influenced by differences in personality, family history, culture, and other features. It is identified that each of these components highlighted above might be available, but in different degrees without compromising the general quality of PCC. Broadly speaking, the assumption is that a parent-child dyad that embraces all or most of these components, as early as possible in a child’s life, and continuous from that moment on, is extremely likely to capture the type of relationship that PCC attempts to establish than if these components were lacking, inconsistent, and/or introduced later in a child’s life.

Also, for a child to recognize and take notice of this climate of trust in the family, the support, openness, protection, encouragement, autonomy, closeness, warmth, and attachment are all communicated orally or otherwise by parents in the family. However, it is not only love, warmth, and affection alone that are expressed in the family, but also feelings and ideas are also exchanged and acknowledged. This has an iterative consequences which conveys the impression that, the more and more these components are communicated, it is the more and more they add to a climate of trust that, in return, makes future communication more productive and even more resilient to unhealthy behaviours. In view of this, both communication and an underlying climate of trust become mainly significant as parents offer structure, discipline, monitoring, and guidance (attitude). Communication and climate of trust also stimulate the mutual influence of spending time together which in return becomes another prospect for communication, for fun as well as serious interaction, and for even more incremental building of trust. Therefore, the result is an everlasting intimacy between parents and children that is mutual, continuous over time, and resilient to risky sexual behaviour.

In sum, parents who openly express their beliefs and expectations to their adolescents, communicate their interests and emotions to them early and frequent. They also endeavour to monitor them in many ways including the selection of playmates and role models for their wards. These parents bring up children who are much more likely to avert a host of risky sexual behaviour than parents who fail to do that. The greater benefit of parent-child relationships seems to be the best protection of all. The review has unearthed that researchers in Ghana have not explored the elements of parent-child connectedness effectively to predict those elements that are considered to be important, influence closeness in a relationship and support the defensive role that PCC plays in delaying and reducing adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour and, therefore, should be promoted. Also, no published studies are addressing parent-child connectedness and risky sexual behaviour among adolescents in the Assin South District, hence, the need for the study.

Materials and methods

Study context

The study was carried out at Assin South District in the Central Region, Ghana were risky sexual behaviours still seems to be a common practise. Therefore the main aim of the article was to understand the influences of parent-child connectedness on adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. The researchers therefore investigated the influences of climate of trust parents built and maintain with their children, parents’ intention to engage children in communication, appropriate structure of home parents built with children and finally parent-child time shared on adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. The findings of the study might provide to parents the hints about how PCC works to serve as a super protective barrier to adolescents’ risky sexual behaviours in the Assin South district.

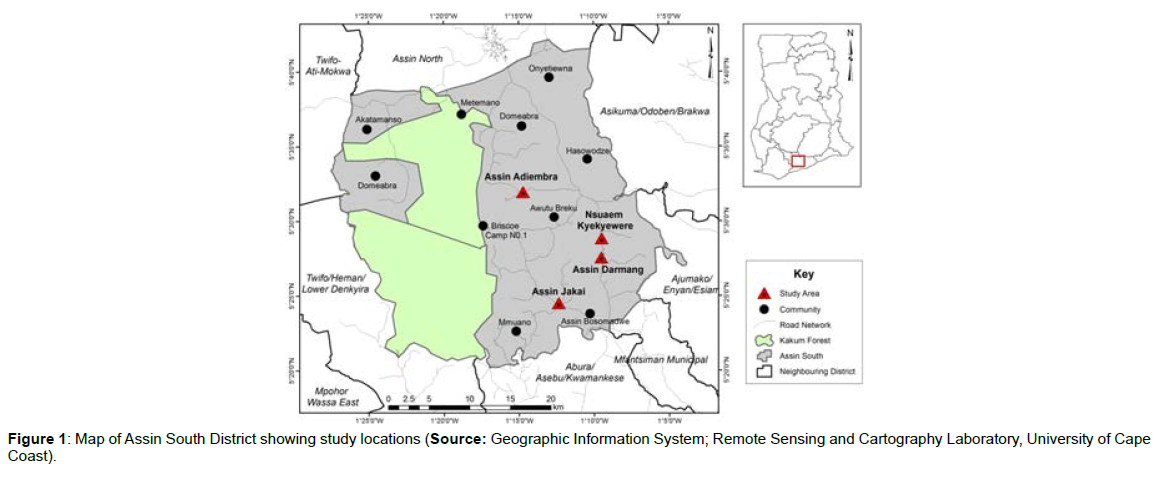

The Assin South District shares boundaries with Twifo Hemang Lower Denkyira District on the West, Abura Asebu Kwamankese District on the South, Asikuma Odoben- Brakwa District and Ajumako Enyan Essiam District on the East and Assin North Municipal on the Northern border .

According to the 2010 Population and Housing Census, the total population of the District is 104, 244 with 2.9 per cent as the growth rate. The population is made up of a slightly high number of 53, 308 females (51.1%) compared to 50, 936 males (48.9%).

Assin South District has not been spared from the global HIV and AIDS pandemic (GSS, 2012). The total number of cumulative AIDS cases at the end of December 2006 was 100 (Assin-South District Mutual Health Insurance Scheme, 2006). The District recorded 22 maternal deaths among adolescents aged 15-19 years from 2004 to 2006 and family planning coverage by the District from 2003 to 2006 was 20 per cent [46].

The Assin South District recorded 19.6 per cent and 17.5 per cent of births attributed to teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19 years in 2015 and 2016 respectively [47,48] identifies that the phenomenon of adolescent pregnancy has become one of the serious challenges of social welfare in Ghana. However, a greater number of adolescents are being identified with the situation which therefore requires immediate and pragmatic attention. Figure 1 shows the map of the study area (Figure 1).

Respondents

Respondents, parents and adolescents in the Assin South District constituted the target population. The accessible population covered parents aged 30-59 years and adolescents aged 15-19 years. Based on this, parents aged 30-59years and adolescents aged 15-19 years in the Assin South District were enrolled in the study and the results were used to describe the whole larger group of adolescents in the district.

Sampling procedures and sample size

A multistage sampling procedure was adopted for the study. The first stage was the random selection of Assin South District out of the 22 metropolitan, municipals and districts assemblies within the Central Region. To ensure that the entire district is covered in the study, the district was divided into four (4) zones where each zone constituted three settlements. Out of the four zones, one settlement each was selected for the study. Zone One constituted Assin Adiembra, Assin Anyinabrim and Assin Asamankese. The following settlements also formed Zone Two; Assin Darmang, Assin Ongwa (Aworoso) and Assin Ngresi. Zone Three was made up of Gyakai, Ongua, Nsuaem- Kyekyewere, while Zone Four constituted Nsuta, Assin Jakai and Assin Akyiase.

The second stage was the selection of a settlement from each of the zones to form a study site for the study; simple random sampling approach was applied. With this approach, the names of all the settlements in each zone were written on pieces of paper and folded. The folded papers were kept in a separate box and well shaken to adequately mix them up. A volunteer was called to pick one folded paper at a time from each of the boxes and the names of those settlements picked constituted the chosen settlements for the study. The selection was done without replacement.

One hundred (100) respondents were selected from each study site. In each study site, 50 per cent of the sample was allocated to parents (50 respondents per study site) and the other 50 per cent to the adolescents (50 respondents per study site). Based on the male-female ratio of the population of parents and adolescents aged 15-19 years based on the 2010 Ghana Population and Housing Census, 27 females and 23 male respondents were selected from each study site.

Finally, the third stage was the selection of the respondents. Now, to reach the respondents, the researcher made a rough estimation of the number of houses within each selected study site. Then, a probability sampling method utilizing a systematic random sampling approach was employed to select the respondents for the study. Systematic random sampling is settled on the selection of respondents placed at a certain predetermined interval called the sampling fraction. This is relevant for small scale studies and one advantage of it is that one can use it without having a sample frame as in a location where dwellings are well arranged in rows, blocks or along a river or main road.

To select the first respondents, a sample fraction was determined. So, based on the sample fraction, the first respondent was selected. The sample fraction was determined by dividing the total number of houses within each study site by the number of females, (i.e., 27) and males, (i.e., 23) to be selected within each study site. For example, if the number of houses within a study site is say 150, then, the sampling fractions will be 150/27 = 5.5 for females and 150/23 = 6.5 for males. Since the sampling fractions are decimal numbers, the rounding was done after adding the sampling fraction to the decimal number found in the previous step. In this regard, for the female sample, a random number between 1 and 5 was first generated. So, for example, if the random number generated is 2, then, starting from a major landmark such as lorry station/bus stop, post office, clinic/hospital, and church/ mosque and so on, following a serpentine order, the 2nd house was selected, followed by the 2 + 5 = 7th house, 7+5 = 12th house and so on. In each selected house, one parent and one adolescent were randomly sampled for the study and this served as parent-child pair. Adolescents were the index respondents and were used as leads for selecting parents. In the case where there were sampled house(s) with no eligible respondents, the researcher repeated the above process, starting from another major landmark, until the required sample was attained. The same procedure was adopted for a parent-male sample and also the adolescents aged 15-19 years at all the study sites (Table 1).

| Zone | Name of study site |

|---|---|

| One | Assin Adiembra |

| Two | Assin Darmang |

| Three | Nsuaem-Kyekyewere |

| Four | Assin Jakai |

Table 1: List of Study Sites by Zones.

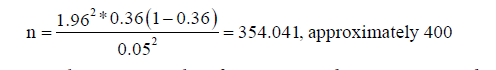

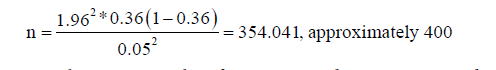

Sample size estimation

In order to calculate the sample size manually, Cochran’s sample size formula for estimating sample size was employed to estimate the sample size for the study. It is recommended to be the most befitting formula for calculating sample size. To utilize this formula, the preferred level of precision and the population size should be known [49]. With the help of this formula, sample size was estimated at 354 as follows:

n = sample size

Confidence level set at 95% (1.96)

The p-value was set at 0.05.

z = standard normal deviation set at 1.96

d = degree of accuracy desired at 0.05

p = proportion of parents aged 30-59 years and adolescents aged 15-19 years was 36 percent

This proportion was obtained by adding the proportion of parents aged 30-59years (26475) to that of adolescents aged 15-19 years (11099) which is equal 37574. The figure obtained (37574) as the proportion of parents aged 30-59 years and adolescents aged 15-19 years was further divided by the total population of the Assin South District (104244) to obtain 0.36. Mathematically, 37574/104244 = 0.36.

Sample size was, therefore, estimated at 400 respondents for the study. The extra 46 respondents were added to cater for refusal, incomplete information and non-responses.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval was sought from the University of Cape Coast Institutional Review Board (UCCIRB) and a letter of introduction from the Population and Health Department. Subsequently, permission was obtained from the Assin South District Assembly. In the field, informed consent was obtained from the parents and adolescents aged 18-19 years and adolescents below 18 years also assented after their parents have consented. The researchers personally identified themselves to the respondents and the option of opting out of the study reiterated at each stage of the interview. The rationale and nature of the research were explained in clear terms to respondent’s right from the beginning of the study. Anonymity and free choice of participation with no undue consequences to respondent’s decisions were ensured. During the fieldwork, all forms of identification including respondents’ names, addresses and telephone numbers were avoided.

Research instruments for data collection

In line with the quantitative approach which was employed in the study, structured questionnaires were used to obtain data from both parents aged 30-59years and adolescents aged 15-19 years. The structured questionnaires were used to elicit data on the climate of trust parents build and maintain with children; parents’ intention to engage children in communication; the kind of structure of home parents build with children; parent-child time shared and the specific elements of parent-child connectedness that are considered to support closeness in a relationship and also influence the effective role PCC plays in delaying and reducing risky sexual behaviour among adolescents. Separate questionnaires were used to solicit similar data from parents and adolescents. The questionnaires served as a framework for the researcher which composed of close and open-ended questions and also posed specific and structured questions on the key issues proposed in the objectives and the conceptual framework of the study. The research instrument formulated was based on literature and the conceptual framework of the study. Already compiled and tried survey instruments were also reviewed and those deemed appropriate to the study were integrated into the design of the research instrument. Items on the research instrument measuring PCC were extracted from PCC survey. Parental attitude items were compiled from conceptual models and a systematic review survey [50]. Moreover, dating and risky sexual behaviour items were extracted from parent-child sexuality communication as well as parental factors and sexual risk-taking surveys [51]. The questionnaire was preferred because according to Sansoni (2011) it ensures a wider coverage and enables the researcher to reach out to a large number of respondents in a short period and helps to provide data which cannot be provided when using other approaches in same short period. This minimizes the problem of nocontact which other methods face (Figure 2).

Pretesting of questionnaires

To check for the ambiguity of the questionnaires for the study, they were given to course mates, peers and the supervisor to read through. Suggestions that were made helped in modifying and restructuring the questionnaires appropriately. The researcher also carried out a pilot study on parents aged 30-59 years and adolescents aged 15–19 years in the Assin North Municipality which shares a border with the Assin South District to ensure the acquisition of adequate knowledge about the respondents. The Assin North Municipality was chosen for the pilot study because it is considered to share common characteristics with the Assin South District. This is in line with the assertion by Bordens and Abbott (2002) that “… once you have organized your questionnaires, it should be administered to a pilot group of respondents matching your main sample to ensure that the items are free from ambiguity” (p. 225). They further posited that after the piloting in a small sample, you then administer your questionnaires to your main sample. The pilot study took place 11 days before the actual data collection week. This was just to allow for final adjustments and modifications to the questionnaire. After the pilot study, questions found not relevant were reformulated.

Variables and measurements

The independent variable was parent-child connectedness (PCC) and the outcome variable was risky sexual behaviour. All the variables were chosen based on the PCC, the conceptual framework adapted for the study and the literature [52,53].

According to lezin et al. (2004), measurement of PCC dwells on the following constructs: attachment/bonding, warmth/caring, cohesion (closeness and conflict), support/involvement, communication, monitoring/control and autonomy. Lezin and colleagues in 2004 highlighted 71 examples of measures from each of the constructs. These measures were assumed to be possible risk and protective factors of PCC. Positive (“+”) and the negative (“-”) symbols were used to illustrate possible risk and protective factors. For instance, the positive (“+”) symbol signals a possible protective factor while the negative (“-”) symbol shows a possible risk factor. In addition, 27 other possible risk and protective factors are listed for which measures were not found, but are supported in the literature as influences on the PCC construct. This positive (“+”) and the negative (“-”) symbols approach used to illustrate possible risk and protective factors were emerged to be a bit technical to the current study because binary logistic regression analysis does not give negative (“-”) odds ratios therefore, the current study adopted odds ratios less than 1 as a possible protective factor to risky sexual behaviour while odds ratios greater than 1 as a possible risk factor to risky sexual behaviour.

The possible variables that were endorsed by Lezin and colleagues (2004) to measure attachment/bonding construct are; parent and child share thoughts and feelings, parent and child feel close, child wants to be like mother/father (identification), parent and child seem “in tune”, mutual warmth, happy emotional tone, smiling, and laughing.

Those that measure warmth/care construct are; parents help child, parents understand what child needs and wants, empathy, affection, reciprocity, rejection, coldness, indifference, parent’s “childcenteredness”, perceived caring, feeling loved and wanted, neglect, acceptance, understanding, respect, and responsiveness.

Concerning cohesion (closeness and conflict) construct measurement, the possible variables agreed on by Lezin et al. (2004) are: mutual satisfaction with relationship, spend time together, joint activities, arguments, supportiveness, togetherness,get along well, commitment, religious values, family stresses, keep in touch with relatives, family rituals, joint decision-making, problem-solving.

Furthermore, regarding measurement of support/involvement construct, the following variables were outlined by Lezin et al. (2004) namely: parent affirms child’s ideas, perspectives, stories, encouragement, appreciation, attend school, sports events, help choose courses, meet with teachers/counselors, parents set high expectations and parents provide guidance.

With respect to communication construct, Lezin and colleagues (2004) outlined: intrusiveness [parent interrupts, dominates child’s conversation], use of explanation and reasoning, frequency of discussions, spend time talking together, share thoughts and feelings, clarity of messages about risk behaviour and values, child’s comfort discussing problems with parent, openness and listening.

For monitoring/control construct, the variables were: a. rules governing; bedtime, homework, TV, alcohol/drugs, dating, clarity of rules and agreement with parent rules; b. monitoring: child calls if late, parents know if not home, child can reach parents, parents know where child is after school and with whom, parents know child’s friends, child’s perception of parents’ knowledge of where he/she goes and whom he/she is with, parent’s presence before and after;- school, dinner, bedtime, weekends, child’s perception of parent’s strictness, how often child goes where told not to, how difficult it is to know where child goes, adult supervision of children’s parties, over-protectiveness; “babying”, controlling behaviour-blame, guilt, rejection/withdrawal, erratic emotional behaviour, punishment, type of punishment -restrict activities, slapping/hitting, arguing, name-calling; parents knowledge of child’s friends, activities and whereabouts, parents’ awareness of child’s risk behaviour, consistency in rules and discipline.

Lastly, autonomy construct measurement dwelt mainly on: child makes own decisions, child’s perception of parent’s noncoercive, democratic discipline, encouragement of child’s own ideas, intrusiveness, locus of control, voice in family decisions, trust, respect for child’s individuality.

Fieldwork and data collection procedure

Data collection started after the UCCIRB had approved the research protocol. The collection of data took place at the various study sites namely; Assin Adiembra, Assin Darmang, Nsuaem-Kyekyewere and Assin Jakai on 23rd of June, 2020 and ended on 5th of July, 2020 at the Assin South District in the Central Region of Ghana. In all, 13 days were used to collect the data from the field. Each community was contacted separately to fix the befitting time to administer the questionnaire. The questionnaires were administered in person to all the communities. It was purposely done to: explain the goals for the research; direct the parents’ and adolescents’ attention to their rights during the study; clarify the instructions for answering and obtain a good return rate and more accurate data.

Since the researcher could not administer the questionnaires alone, four research assistants were hired and trained on the purpose of the study to assist in the administration of the questionnaires. The questionnaires were administered and taken that same day. To ensure successful collection and sorting of the questionnaires, each questionnaire was given a serial number according to the separate communities.

In the field, two sets of interviews were conducted in each household for the parent–child dyad to avoid spying and to ensure openness and truthful responses. Generally, parents were first interviewed before the child.

Data quality concerns

Recently, in social science research, data quality has become a pertinent concern and mainly pivoted on validity and reliability. Reliability tries to assess the internal consistency of results across variables within a test. Cronbach’s alpha was adopted to test for the internal consistency reliability of the data collected from the field because according to Cortina (1993), it is rated to be the most utilized internal consistency for measurement and it is mostly viewed as the mean of all possible split-half coefficients. Broadly speaking, it is an earlier procedure for computing an internal consistency which helps to find out how all variables on the analysis correlate to all other variables. Per the reliability test on the PCC and RSB data collected from the field, it emerged that Cronbach’s alpha rated the data as acceptable with a reliability of α = 0.63 and with a scale comprising 43 items, mean of 74.95, variance of 41.04 and standard deviation of 6.41. According to Griethuijsen, et al. (2014) a general accepted rule is that alpha of 0.6-0.7 indicates an acceptable level of reliability and that data is useful.

Effort and befitting approaches were also made to ensure validity of data collected from the field which comprise pretesting of questionnaire before the actual data collection. As well, standardized research instruments which were used in previous PCC, and PCSC survey as well as parental attitude survey were adopted. Again, in the study, the questions asked of respondents served as the premise of the findings and conclusions. These questions constituted the ‘input’ for the research conclusions (the ‘output’). Therefore, in order to achieve a validity, effort was made to ensure that this input passes through a series of steps namely; the selection of a sample, the collection of data, the processing of data, the application of statistical procedures and the writing of a report. It became necessary to ensure that these inputs go through series of steps because the researcher did not want the manner in which all of these are done to affect the accuracy and quality of the study conclusions.

Data analysis procedure

The analysis was based on the completed questionnaires from the field. The data collected were grouped under sub-headings and categories based on how the questionnaires were structured and the purpose of the study such that each open and close-ended question provided answers for each of the research objectives. Data collected from the field were first cross-checked to ensure that they were correct and had no errors in them. Questions that requested respondents to choose more than one option were re-coded as well as the openended questions to enable easy entry and analysis. The data were then transferred to the computer and processed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 and Stata.

Frequency distribution was used to summarize demographic data, responses on climate of trust, communication, structure of home, time shared and PCC elements that support closeness in a relationship by parent-child dyad. The Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence was used to test the four statistical hypotheses postulated in the study to either accept or reject the null hypotheses. However, the binary logistic regression analysis was also run on the various results to identify possible risk factors and protctive factors to adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour.

Results

This section deals with the presentation and interpretation of the data analysis. This is done in three sections. The first part focuses on descriptive statistics on adolescents’ and parents’ data. The second section examines the results from the Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence and the last section is on the binary logistic regression analysis.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. The respondents comprised 54.8 per cent females and 45.2 per cent males. Nearly half (48.6%) of the parents in the sample were between the ages of 40 and 49 years while about a quarter (24.9%) were in the 30-39 age group. Regarding educational level, only 2.3 per cent of the parents had tertiary education compared to 44 percent who completed primary school. Whereas self-employment was a dominant category of employment status constituting over half (50.3%) of the total respondents, the employed category was the least (11.3%). In terms of religious affiliation, Christianity dominated (81.9%) and those not identified with any religion were 1.7 per cent.

Nearly a third (31.6%) of the adolescents were 19 years old while about 10 per cent were 17 years old (Table 2). More than half (56.5%) of the adolescents indicated that they were still in school. Out of the 20 parents who were identified as employed, about 5 percent earned more than GH¢1500.00.

| Parents (n=177) | Adolescents (n=177) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | % | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 45.2 | 45.2 |

| Female | 54.8 | 54.8 |

| Age group in years | ||

| 30-39 | 24.9 | |

| 40-49 | 48.6 | |

| 50-59 | 26.6 | |

| Age in years | ||

| 15 | 16.4 | |

| 16 | 26 | |

| 17 | 9.6 | |

| 18 | 16.4 | |

| 19 | 31.6 | |

| Educational level | ||

| None | 15.8 | |

| Primary | 44.1 | 1.1 |

| JHS | 15.3 | 29.4 |

| Secondary | 22.6 | 12.4 |

| Tertiary | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| Still in school | 56.5 | |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 11.3 | |

| Unemployed | 38.4 | |

| Self-employed | 50.3 | |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| No religion | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Christian | 81.9 | 81.9 |

| Muslim | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| Traditionalist | 8.5 | 8.5 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of parents and Adolescents.

Parent–child connectedness

PCC has the potential to empower adolescents to pull off the numerous problems connected to youthfulness. There is an indication that when PCC is established, maintained and increased in a family, the outcome is an everlasting strong intimacy among family members devoid of conflicts (Figure 3).

This section of the chapter analyses climate of trust as one element of the parent-child connectedness. Specifically, the focus is on eight variables of a climate of trust, namely, support, openness, protection, encouragement, autonomy, warmth/care as well as closeness and attachment. The reason for this aspect of the chapter is a need to understand if parents build and maintain a climate of trust with children in the family which can be used to conclude if it positively or negatively influences adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. These variables have been used to assess if parents build and maintain a climate of trust with children in the family.

Climate of trust parents build and maintain with children

To obtain data on the climate of trust parents build and maintain with children, research objective one was formulated. The respondents were, therefore, asked series of questions to examine if parents built and maintained a climate of trust with children. The results are presented in Table 3.

| Parents (n=177) |

Adolescents (n=177) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Climate of trust | (%) | (%) |

| Share thoughts and feelings with a child | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Frequency for sharing thoughts and feelings | ||

| Often | 100.0 | 80.2 |

| Occasionally | 19.8 | |

| Emotional tones present when parents and adolescent come close | ||

| Happiness, smiling and laughter | 100.0 | 97.2 |

| Sorrow, regretful and misunderstanding | 2.8 | |

| Warmth expression towards adolescents | ||

| Empathy, affection and reciprocity | 99.4 | 96.6 |

| Rejection, coldness and indifference | 0.6 | 3.4 |

| Child feel loved and wanted | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Indicator showing child feel loved and wanted | ||

| Spend time together, have joint activities and supportive | 94.4 | 87.6 |

| Joint decision making and problem solving | 5.6 | 12.4 |

| Parent support child | ||

| Yes | 95.5 | 100.0 |

| No | 4.5 | |

| Grant child autonomy | ||

| Yes | 95.5 | 80.2 |

| No | 4.5 | 19.8 |

| Offer encouragement to a child | 100.0 | 100 |

| Ways of offering child an encouragement | ||

| Praise child | 27.7 | 27.1 |

| Celebrate child’s success | 72.3 | 72.9 |

| Why child encouragement | ||

| To achieve a target, establishment of trust and strengthen brokenhearted | 71.2 | 83.6 |

| Feel wanted, belonged, motivated, disciplined and to offer guidance | 28.8 | 16.4 |

| Opened to a child | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Ways parents are opened to a child | ||

| Chat together | 85.9 | 85.9 |

| Play together | 14.1 | 14.1 |

| Why opened to a child | ||

| Due to intimate relationship | 65.5 | 64.4 |

| Building child’s charisma | 19.2 | 22.0 |

| Better guidance and appropriate nurturing | 15.3 | 13.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Source: Fieldwork, 2020 | ||

Table 3: Climate of trust parents build and maintain with children.

On sharing thoughts and feelings with adolescents, the results show that all respondents (both parents and adolescents) reported that parents share thoughts and feelings with adolescents. On whether thoughts and feelings are shared often or occasionally, 87.6 per cent of parents and 80.2 per cent of adolescents said parents often shared thoughts and feelings with adolescents. Concerning the emotional tones that are present when parents and adolescents come close to each other, the results discovered that all parents and 97.2 per cent of adolescents reported happiness, smiling and laughter as the emotional tones (Table 3).

Parents were asked to indicate how they expressed warmth towards adolescents and the results revealed that almost all the respondents (parents 99.4 per cent and adolescents 96.6 per cent) stated empathy, affection and reciprocity as the procedures through which parents expressed warmth towards adolescents. The analysis regarding if parents are supportive towards adolescents or not showed that a little above ninety-five per cent (95.5%) of parents and all the adolescents said parents are supportive. When asked whether adolescents were autonomous or not, the outcome revealed that 95.5 per cent of parents and 80.2 per cent of adolescents reported that adolescents are autonomous (Table 3).

Parents were asked to indicate whether they offer encouragement to adolescents. The results revealed that all the respondents (parents and adolescents) indicated that parents offer encouragement to adolescents. Concerning the reasons why parents offer encouragement to adolescents, parents were asked to indicate why they encourage adolescents and the outcome was that 71.2 per cent of parents and 83.6 per cent of adolescents stated that parents want adolescents to achieve a target, establish trust in parents and also to strengthen adolescents who are broken-hearted (Table 3).

On openness, parents were asked whether they were open to adolescents or not and the result showed that all the respondents (parents and adolescents) reported that parents were open to adolescents. When asked ways parents are open to adolescents, the results revealed that 85.9 per cent of parents and 85.9 per cent of adolescents said parents are opened to adolescents by chatting together (Table 3).

When asked why parents are open to adolescents, the results revealed that 65.5 per cent of parents and 64.4 per cent of adolescents reported that it is due to intimate relationship while 15.3 per cent of parents and 13.6 per cent of adolescents indicated better guidance and appropriate nurturing. In order to be able to identify whether PCC has made an impact on adolescents’ sexual life, they were asked some specific questions regarding dating and risky sexual behaviour. The results are presented in (Table 4).

Concerning dating, adolescents were asked to stipulate whether they had ever dated or not and the results indicated that 59.9 per cent adolescents had never dated while 40.1 per cent adolescents reported that they had ever dated (Table 4).

Among the 71 adolescents who were identified to have ever dated,about 65 per cent had ever dated 1-5 partners, about 34 per cent had at least dated 6-10 sexual partners while 1.4 per cent had dated 11-15 sexual partners. Out of the 71 adolescents who were identified to have ever dated, about 92 per cent had been in dating for about 1-5 years whilst 8.5 per cent started dating 6-10 months ago.

Regarding risky sexual behaviour, adolescents were asked to indicate whether they had ever practised any risky sexual behaviour or not and the results obtained showed that 63.8 per cent adolescents reported that they had never practised any risky sexual behaviour while 36.2 per cent adolescents reported that they had ever engaged in risky sexual behaviour (Table 4).

| Factor | Adolescents (%) (n=177) |

|---|---|

| Ever dated | |

| Yes | 40.1 |

| No | 59.9 |

| Ever practised risky sexual behaviour | |

| Yes | 36.2 |

| No | 63.8 |

| Total | 100 |

| Source: Fieldwork, 2020 | |

Table 4: Adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour.

Among the 64 adolescents who were identified to have ever practised risky sexual behaviour, about 63 per cent (62.5%) had ever engaged in mouth to genital contact and started sexual activity at a younger age, 28.1 percent indulged in multiple sexual partners and sex without a condom while 9.4 percent practised unprotected sex.

In Table 5, chi-square analysis examining the relationship between climate of trust and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour is presented. This analysis was run to test the hypothesis that there is no relationship between climate of trust and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. No statistically significant relationship was found between climate of trust and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour with respect to the p-value of the various explanatory factors studied under climate of trust namely; thoughts and feelings sharing frequency [p=0.892], family emotional tones [p=0.260], parental warmth expression towards adolescents [p=0.473], indicator showing that child feels loved and wanted [p=0.620], parental supportive strategy towards adolescents [p=0.436], child being autonomous [p=0.797], parental protection strategy towards adolescents [p=0.129], parental encouragement strategy towards adolescents [p=0.633], why parents encourage a child [p=0.828], parental openness strategy towards adolescents [p=0.184] as well as why parents are open to adolescents [p=0.297] and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour (Table 5).

| Factor | Ever practised risky sexual behaviour(%) | Never practised risky sexual behaviour (%) | Total n(%) | Chi square | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoughts and feelings sharing frequency | 0.018 | 0.892 | |||

| Often | 35.9 | 64.1 | 142(100.0) | ||

| Occasionally | 37.1 | 62.9 | 35(100.0) | ||

| Family emotional tones | 1.267 | 0.26 | |||

| Happiness, smiling and laughter | 35.5 | 64.5 | 172(100.0) | ||

| Sorrow, regretful and misunderstanding | 60 | 40 | 5(100.0) | ||

| Warmth expression | 0.515 | 0.473 | |||

| Empathy, affection and reciprocity | 37.1 | 64.3 | 171(100.0) | ||

| Rejection, coldness and indifference | 50 | 50 | 6(100.0) | ||

| Indicator showing child feel loved and wanted | 0.246 | 0.62 | |||

| Spend time together, have joint activities and supportive | 35.5 | 64.5 | 155(100.0) | ||

| Joint decision making and solving child’s problem | 40.9 | 59.1 | 22(100.0) | ||

| Support strategy | 0.607 | 0.436 | |||

| Attend sport events together and meet with school teacher | 46.2 | 53.8 | 13(53.8) | ||

| Attend school and help child choose a course of study | 35.4 | 64.6 | 164(100.0) | ||

| Child being autonomous | 0.066 | 0.797 | |||

| Autonomous | 36.6 | 63.4 | 142(100.0) | ||

| Not autonomous | 34.3 | 65.7 | 35(100.0) | ||

| Protection strategy | 2.309 | 0.129 | |||

| By giving simple information | 18.8 | 81.2 | 16(100.0) | ||

| Listen to child, offer guidance and pay attention to anything suspicious | 37.9 | 62.1 | 161(100.0) | ||

| Encouragement strategy | 0.228 | 0.633 | |||

| Praise child | 33.3 | 66.7 | 48(100.0) | ||

| Celebrate child success | 37.2 | 62.8 | 129(100.0) | ||

| Why child encouragement | 0.047 | 0.828 | |||

| Achieve a target, establishment of trust and strengthening child brokenhearted | 35.8 | 64.2 | 148(100.0) | ||

| Feel wanted, belonged, motivated, disciplined and guidance | 37.9 | 62.1 | 29(100.0) | ||

| Openness strategy | 1.768 | 0.184 | |||

| Chat together | 34.2 | 65.8 | 152(100.0) | ||

| Play together | 48 | 52 | 25(100.0) | ||

| Why opened to a child | 2.43 | 0.297 | |||

| For intimate relationship | 39.5 | 60.5 | 114(100.0) | ||

| Building child’s charisma | 25.6 | 74.4 | 39(100.0) | ||

| For better guidance and appropriate nurturing | 37.5 | 62.5 | 24(100) | ||

| Note: Row percentages in parenthesis, chi square significant at (0.001)***, (0.01)**, (0.05)* Source: Fieldwork, 2020. |

|||||

Table 5: The relationship between climate of trust and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour.

Following the Chi square test of independence results on climate of trust and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour, further analysis was run using the binary logistic regression to determine how the respective categories of the explanatory factors under climate of trust drive adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. However, this analysis became necessary in order to be able to tell among the various categories of explanatory variables studied those that were possible risk factors and those that were possible protective factors to adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. The results are presented in Table 6 (Table 6).

It emerged in Table 6 that, offering encouragement to adolescents on their own ideas and also respecting their individuality was observed as statistically significant variable that seems to have influenced adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour at P<0.022, (OR=7.486, 95%CI[1.331-42.090]). This variable revealed that adolescents that stated that parents offer encouragement to them on their own ideas and also respecting their individuality are 7 times as likely as the adolescents that reported that parents allow them to make their own decisions and add their voice in family decisions. Moreover, the rest of the variables studied under climate of trust and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour were not statistically significant which could be as a result of chance.

| Factor | Odds Ratio | P-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency for sharing thoughts and feelings (Often=1.0) | ||||

| Occasionally | 0.995 | 0.991 | 0.423 | 2.339 |

| Emotional tones present when parents and adolescent come close (Happiness, smiling and laughter=1.0) | ||||

| Sorrow, regretful and misunderstanding | 3.701 | 0.192 | 0.518 | 26.442 |

| Warmth expression towards adolescents (Empathy, affection and reciprocity=1.0) | ||||

| Rejection, coldness and indifference | 2.517 | 0.291 | 0.454 | 13.947 |

| Indicator showing child feel loved and wanted (Spend time together, have joint activities and parents are supportive=1.0) | ||||

| Joint decision making and problem solving | 2.298 | 0.099 | 0.856 | 6.171 |

| Parents supportive strategy (Attend sport events with child and meet with child teacher=1.0) | ||||

| Accompany a child to school and help child to choose a course of study | 0.495 | 0.273 | 0.141 | 1.74 |

| Autonomy granting strategy (Allows me make my own decisions and voice in family decisions=1.0) | ||||

| Offer me encouragement on my own ideas and respect for my individuality | 7.486 | 0.022* | 1.331 | 42.09 |

| Parents protection strategy (By giving simple information=1.0) | ||||

| Listen to me, offer guidance and pay attention to any suspicious behaviour | 1.847 | 0.386 | 0.462 | 7.379 |

| Why parents encourage a child (To achieve a target, establishment of trust and strengthen broken-hearted=1.0) | ||||

| Feel wanted, belonged, motivated, disciplined and to offer guidance | 0.847 | 0.734 | 0.326 | 2.203 |

| Ways parents are open to a child (Chat together=1.0) | ||||

| Play together | 1.575 | 0.345 | 0.614 | 4.043 |

| Why parents openness (Due to intimate relationship and trustworthiness=1.0) | ||||

| Building child’s charisma | 0.403 | 0.053 | 0.161 | 1.01 |

| For better guidance and appropriate nurturing | 0.791 | 0.636 | 0.3 | 2.089 |

| Constant | 0.565 | 0.521 | 0.099 | 3.235 |

| Source: Fieldwork, 2020, Chi-square significant at (0.05)* | ||||

Table 6: Binary logistic regression result on climate of trust and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour.

Parents’ intention to engage adolescents in communication

Good communication among family members is critical to the sexual development and overall well-being of adolescents particularly because of the easy and heightened access of adolescents to information through various media. Without proper guidance, adolescents are exposed to inaccurate information that can lead them to risky sexual behaviour [54]. To assess parents’ intention to engage children in communication, several questions were asked to collect data from the respondents to analyse whether parents engage adolescents in communication or not. The questions covered communication intentions, frequency, content and predictors of communication and the results are shown in Table 7 (Table 7).

Regarding communication, parents were asked whether they communicate with adolescents or not and the results indicated that all the respondents (both parents and adolescents) reported that parents communicate with adolescents. Concerning communication intention, parents were asked to indicate their intention behind their communication with adolescents and the results revealed that 27.1 per cent of parents and 35.6 per cent of adolescents reported that, it is for behavioural boundaries while 23.2 per cent of parents and 20.3 per cent of adolescents said it is for building a child’s charisma (Table 7).

With respect to the intention behind communication on opposite sex relationships, majority of the respondents (parents 65.5 per cent and adolescents 75.7 per cent) reported that it is for child’s relationship comfort while 11.3 per cent parents and 10.2 per cent adolescents cited clarity of messages about risky sexual behaviour. In relation to parents’ intention to discuss condom use among adolescents, majority of the respondents (parents 75.7 per cent and adolescents 89.8 per cent) said that it is for STIs protection. When parents were asked to indicate their intention behind the discussions on sexual health matters, 88.1 per cent of parents and 52.0 per cent of adolescents said that it was to help adolescents to reject sexual risk taking (see Table 7).

On whether parents discuss risky sexual related matters with adolescents or not, the result showed that all the respondents (both parents and adolescents) reported that parents discuss risky sexualrelated matters with adolescents. Parents were further asked to indicate their intention behind the discussion of risky sexual behaviour with adolescents and the responses revealed that 54.2 per cent of parents and 85.9 per cent of adolescents said it is to increase adolescents’ knowledge of the adverse effects on risky sexual behaviour and also help adolescents to delay sexual debut whilst, 19.8 per cent of parents and 5.6 per cent of adolescents indicated that it is for the establishment of better interpersonal communication skills among the adolescents (see Table 7).

Parents were asked to indicate whether they discuss risky sexualrelated matters such as opposite sex relationships, condom usage, risky sexual behaviour and sexual health matters often or occasionally with adolescents and the results indicated that all the parents and 59.3 per cent of adolescents stated that it is often (see Table 7).

Regarding who initiates the talks on risky sexual behaviour, all the parents and 80.2 per cent of adolescents indicated that it is parents that initiate the talks. The study collected information on the predictors of communication on risky sexual behaviour and the results revealed that all the parents and 80.2 per cent of adolescents reported that it is parents’ own awareness on sex education (see Table 7).

| Parents (n=177) |

Adolescents (n=177) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Parents’communication intention | % | % |

| Communicate with a child | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Intention behind the communication | ||

| Behavioural boundaries | 27.1 | 35.6 |

| Building child’s charisma | 23.2 | 20.3 |

| Positive social conduct | 23.7 | 18.1 |

| Appropriate nurturing | 26.0 | 26.0 |

| Intention behind talks on opposite sex relationships | ||

| For child relationship comfort | 65.5 | 75.7 |

| Ensure stable relations | 23.2 | 14.1 |

| Clarity of messages about risky sexual behaviour and values | 11.3 | 10.2 |

| Intention behind talks on condoms | ||

| For STIs protection | 75.7 | 89.8 |

| Prevention of unintended pregnancy | 24.3 | 10.2 |

| Intention behind talks on sexual health matters | ||

| Rejecting sexual risk taking | 88.1 | 52.0 |

| Delay sexual debut | 11.9 | 48.0 |

| Discuss topics related to risky sexual behaviour | 100 | 100.0 |

| Intention behind talks on risky sexual behaviour | ||

| Increase knowledge and delay sexual debut | 54.2 | 85.9 |

| Self-efficacy and sexual negotiation skills | 26.0 | 8.5 |

| Better interpersonal communication skills | 19.8 | 5.6 |

| Communication frequency | ||

| Often | 100 | 59.3 |

| Occasionally | 40.7 | |

| Who initiates the talk | ||

| Parent | 100 | 80.2 |

| Adolescent | 19.8 | |

| Triggers of risky sexual behaviour communication | ||

| Parents’ own awareness on sex education | 100 | 80.2 |

| Perceive self-efficacy | 19.2 | |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Source: Fieldwork, 2020. | ||

Table 7: Parents’ intention to engage children in communication.

In Table 8, chi-square analysis examining relationship between parents’ intention to engage adolescents in communication and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour are presented. This analysis was run to test the hypothesis that there is no relationship between parents’ intention to engage adolescents in communication and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. The results show a remarkable difference in the seven (7) components studied under parents’ intention to communicate with adolescents and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. Statistically significant relationships were found among two of the components namely; parents’ intention to communicate with adolescents [p=0.049] as well as parents’ intention to discuss opposite sex relationship with adolescents [p=0.018] and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. However, there was no statistically significant relationships found between the other components namely; intention behind condom usage discussions [p=0.197], intention behind the discussions on sexual health matters [p=0.242], risky sexual behaviour discussion intention [p=0.648], communication frequency [p=0.742] as well as the person that initiates the talks [p=0.892] and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour (Table 8).

| Factor | Ever practised risky sexual behaviour (%) | Never practised risky sexual behaviour (%) | Total n(%) | Chi square | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention behind communication with a child | 7.859 | 0.049* | |||

| Behavioural boundaries | 44.4 | 55.6 | 63(100.0) | ||

| Positive social conduct | 41.7 | 58.3 | 36(100.0) | ||

| Appropriate nurturing | 37.5 | 62.5 | 32(100.0) | ||

| Building child’s charisma | 19.6 | 80.4 | 46(100.0) | ||

| Intention behind talks on opposite sex relationships | 8.086 | 0.018* | |||

| For child relationship comfort | 32.8 | 67 | 134(100.0) | ||

| Ensure stable relations | 32 | 67.2 | 25(100.0) | ||

| Clarity of messages about risky sexual behavior and values | 12(66.7) | 33.3 | 18(100.0) | ||

| Intention behind talks on condoms | 1.663 | 0.197 | |||

| For STIs protection | 34.6 | 65.4 | 159(100.0) | ||

| Prevention of unintended pregnancy | 50 | 50 | 18(100.0) | ||

| Intention behind talks on sexual health matters | 1.367 | 0.242 | |||

| Rejecting sexual risk taking | 40.2 | 59.8 | 92(100.0) | ||

| Delay sexual debut | 31.8 | 68.2 | 85(100.0) | ||

| Intention behind talks on risky sexual behaviour | 0.868 | 0.648 | |||

| Increase knowledge and delay sexual debut | 37.5 | 62.5 | 152(100.0) | ||

| Self-efficacy and sexual negotiation skills | 26.7 | 73.3 | 15(100.0) | ||

| Better interpersonal communication skills | 30 | 70 | 10(100.0) | ||

| Communication frequency | 0.108 | 0.742 | |||

| Often | 37.1 | 62.9 | 105(100.0) | ||

| Occasionally | 34.7 | 65.3 | 72(100.0) | ||

| Who initiates the talk | 0.018 | 0.892 | |||

| Parent | 35.9 | 64.1 | 142(100.0) | ||

| Adolescent | 37.1 | 62.2 | 35(100.0) | ||

| Note: Row percentages in parenthesis, Chi-square significant at (0.001)***, (0.01)**, (0.05)* Source: Fieldwork, 2020 |

|||||

Table 8: Relationship between parents’ communication intention and adolescent’s risky sexual behaviour.

Following the Chi squared test of independence results on parents’ intention to engage adolescents in communication and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour, further analysis was run to identify which categories of the various explanatory factors studied under parent’s intention to communicate with adolescents were possible risk factors or possible protective factors of adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour.

Socio-demographic factors are not factors of parent-child communication intention, but, they were added to the model in order to find out how they also help in driving adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. The socio-demographic factors considered were age, sex, education and religion). This was done because communication is considered to be an important factor that supports closeness in a relationship. The results are presented in Table 9 (Table 9).

It emerged in Table 9 that, building child’s charisma was statistically significant related to adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour at p>0.030, (OR=0.319, 95%CI ([0.114-0.894]). It was observed that adolescents that indicated building child’s charisma were 0.68 times or 68 per cent times less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour relatively to the adolescents that stated for behavioural boundaries (Table 9).

Clarifying messages about risky sexual behaviour was also observed as statistically significant to adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour at p>0.014, (OR=5.684, 95%CI [1.420-22.755]). This identifies adolescents to have 5.7 times more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour compared with adolescents that stated ensure stable relations (Table 9).

| Factor | Odds ratio | P-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention behind communication (Behavioural boundaries=1.0) | ||||

| For positive social conduct | 0.787 | 0.632 | 0.296 | 2.095 |

| For appropriate nurturing | 0.666 | 0.431 | 0.242 | 1.832 |

| Child’s charisma building | 0.319 | 0.030* | 0.114 | 0.894 |

| Intention behind talks on opposite sex relationship (Ensure stable relations =1.0) | ||||

| Child relationship comfort | 1.001 | 0.998 | 0.366 | 2.743 |

| Clarity of messages about risky sexual behaviour | 5.684 | 0.014* | 1.42 | 22.755 |

| Intention behind talks on condom (For STIs protection=1.0) | ||||

| For prevention unintended pregnancy | 0.91 | 0.872 | 0.289 | 2.861 |

| Intention behind talks on risky sexual behaviour (Increase knowledge and delay sexual debut =1.0) | ||||

| Self-efficacy and sexual negotiation skills | 0.733 | 0.653 | 0.188 | 2.85 |

| Better interpersonal communication skills | 0.782 | 0.758 | 0.164 | 3.726 |

| Intention behind talks on sexual health matters (Rejecting sexual risk taking=1.0) | ||||

| Delay sexual debut | 0.596 | 0.169 | 0.285 | 1.246 |

| Communication frequency (Often=1.0) | ||||

| Ocassionally | 0.563 | 0.407 | 0.144 | 2.193 |

| Initiators of communication (Parent=1.0) | ||||

| Adolescent | 2.609 | 0.214 | 0.576 | 11.824 |

| Age (Age 17=1.0) | ||||

| 15 | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.201 | 4.628 |

| 16 | 0.52 | 0.445 | 0.097 | 2.783 |

| 18 | 3.105 | 0.203 | 0.543 | 17.741 |

| 19 | 1.827 | 0.538 | 0.268 | 12.45 |

| Sex (Male =1.0) | ||||

| Female | 1.786 | 0.185 | 0.758 | 4.208 |

| Education ( Still in school=1.0) | ||||

| Secondary | 0.729 | 0.779 | 0.08 | 6.65 |

| JHS | 0.595 | 0.441 | 0.161 | 2.216 |

| Religion (Islamic=1.0) | ||||

| Christianity | 10.659 | 0.075 | 0.786 | 144.57 |

| Traditional | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.035 | 28.74 |

| Constant | 0.05 | 0.102 | 0.001 | 1.818 |

| Source: Field work, 2020, significant at (0.05)* | ||||

Table 9: Binary logistic regression result on parents’ intention to communicate with adolescents’ and adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour.

The kind of structure of home parents build with children

Adolescent years are a period of speedy growth, experimentation, and risk-taking. However, taking risks give adolescents the chance to try their skills and abilities and conceptualize their self-identity [55].However, risks such as engaging in unprotected sex can have harmful and everlasting consequences on an adolescent’s health and well-being [52]. Silk and Morris explain that caregivers are a potent influential people in the lives of their adolescents [56].

To determine the kind of structure of home that parents build with children, several questions were asked to collect data from respondents on the kind of structure of home parents build with children. The questions comprised child monitoring, child discipline, risky sexual behaviour among adolescents and parents’ attitudes towards adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour. The results are presented in Table 10 (Table 10).

Parents were asked to indicate whether they monitor adolescents in the home or not and the results revealed that 89.8 per cent of parents and all the adolescents reported that parents monitor adolescents in the family. Parents who reported that they monitor adolescents were further asked to indicate the kind of monitoring measure they employ to monitor adolescents in the family and the results revealed that 93.1 per cent of parents and 64.4 per cent of adolescents said that parents set rules and regulations for adolescents to obey while 6.9 per cent of parents and 35.6 per cent of adolescents indicated that it is parents strictness (Table 10).

Parents were asked to indicate whether they discipline adolescents or not, the result revealed that all the respondents (both parents and adolescents) said parents discipline adolescents. On the expected type of discipline that parents impose on adolescents, 95.5 per cent of parents and all adolescents said it is democratic. In reference to disciplinary measure parents level on children, a majority of the respondents (parents [86.4%] and adolescents [86.4%]) reported that parents restrict adolescents’ activities and resort to name calling. Concerning why parents discipline adolescents, parents were asked to indicate why they discipline adolescents and the results showed that 60.5 per cent of parents and 91.0 per cent of adolescents indicated that it is for behavioural boundaries and self-control (Table 10). On the other hand, parents were asked to indicate whether they have permissive attitudes towards adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour or not, the results indicated that 98.3 per cent of parents and all the adolescents said parents do not have permissive attitudes towards adolescents’ risky sexual behaviour (Table 10).

| Parents(n=177) | Adolescents(n=177) | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure of home | % | % |

| Monitor a child | ||

| Yes | 89.8 | 100 |

| No | 10.2 | |

| Discipline a child | 100 | 100 |

| Type of child discipline | ||

| Democratic | 95.5 | 100 |

| Don’t know | 4.5 | |

| Child disciplinary measure | ||

| Restrict child’s activities and name calling | 86.4 | 86.4 |

| Slapping and arguing | 13.6 | 13.6 |

| Why child discipline | ||

| Behavioural boundaries and self-control | 60.5 | 91 |

| Positive social conduct and self-sufficiency | 39.5 | 9 |

| Have permissive attitudes towards child’s risky sexual behaviour | ||

| Yes | 1.7 | |

| No | 98.3 | 100 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Source: Fieldwork, 2020 | ||

Table 10: The kind of structure of home parents build with children.