Editorial Open Access

Palliative Care Training Gains Ground in Middle Eastern Countries

Michael Silbermann1*, Kim Shevchenko2 and Vanessa Eaton21The Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC), Haifa, Israel

2The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Michael Silbermann

The Middle East Cancer Consortium

Haifa, Israel

E-mail: cancer@mecc-research.com

Received date: April 23, 2013; Accepted date: April 25, 2013; Published date: April 27, 2013

Citation: Silbermann M, Shevchenko K, Eaton V (2013) Palliative Care Training Gains Ground in Middle Eastern Countries. J Palliative Care Med S3:e001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-e001

Copyright: © 2013 Silbermann M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

“Education is a priority for ensuring the effective implementation of cancer pain relief programs” according to the World Health Organization [1].

It has, therefore, been advocated that training programs for health care workers should be provided in conjunction with existing occupational and academic programs for both physicians and nurses.

The education of physicians in palliative care generally, and in the management of cancer pain in particular varies between countries and between cultures. Generally, palliative care takes place at one of three levels of care: primary care which includes non-specialist (generalist) physicians, family physicians and community nurses working in homecare; secondary care, which includes physicians trained in oncology, surgery or another specialty who see cancer patients and oncology or palliative care nurses; and tertiary care which includes professionals who have specialized in palliative medicine and who make pain relief and symptom management a priority [1].

In the past nine years, The Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC) together with the US National Cancer Institute (NCI), The Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) in the USA, The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the support of governments in the region, as well as institutions such as the Institute for Palliative Medicine at the San Diego Hospice, San Diego CA, and the Palliative Care Institute at Calvary Hospital in New York City, NY, have taken steps to improve physicians and nurses training in cancer pain control and palliative care, in accordance with recommendations issued by the WHO [2-7].

These initiatives have resulted in the creation of new palliative care services in cancer centers in the Middle East region, support for existing homecare services in the community and the establishment of a new Non-Governmental Society for cancer palliation. Overall, these developments are indicators of the increasing recognition of cancer pain relief and palliative care as an essential component of cancer treatment and as important subjects for professional education and training.

In the Middle East, professionals face the challenges of sharing expertise and skills in palliative care and end-of-life care with primary care physicians and residents in oncology, medicine, pediatrics, surgery and anesthesiology, using training formats that have been proven effective in improving clinical practice.

The attitudes and competencies required to provide highquality palliative care overlap substantially with those required in providing excellent primary care [8]. These include communication skills, an understanding of the patient’s “life world”, commitment to comprehensive, integrated care of the patient and family, attention to psychosocial and spiritual concerns, and an emphasis on quality of life and maximizing function while respecting the patient’s values, goals and priorities in managing his/her illness [8]. Of special importance is the provision of supportive care in the community while responding to cultural diversity. Many of these characteristics fall under the rubric of relationship-centered care [9]. Yet, current medical and nursing education inadequately prepares healthcare professionals for interdisciplinary collaboration, an essential component of palliative care.

A recent study evaluated a palliative care training intervention for medical and social work students [10]. The intervention group students participated in a series of four training sessions over four weeks while the control- group students received only written materials after the training intervention. The intervention included experiential methods to promote interdisciplinary interaction aimed at fostering communication, exchange of perspectives, and building mutual trust and respect. The outcome of this intervention was a significant increase in perceived role understanding by the participants in the sessions as compared with the control group. Hence, educational intervention improves role understanding early in the process of professional socialization [10].

A recent survey studying the perceived educational needs in the area of palliative care [11] found that while the residents thought that pediatricians should have an important role in providing palliative care, they reported minimal training, experience, knowledge, competence and comfort provision in virtually all areas of palliative care for children. The residents wanted more training regarding pain management and communication skills. Hence, pediatric residents view palliative care as important for primary care physicians and desire more education [11]. In another survey in India, clinical residents in a tertiary care hospital were assessed as to the awareness, clinical knowledge, and education and training aspects of palliative care [12]. It became apparent that clinicians in India need to be provided with focused skills and training to be enable them to deliver quality palliative care to the large number of patients with incurable cancer. Palliative care, therefore, should be an integral part of clinical residency programs [12].

Few studies have assessed the efficacy of communication skills training for postgraduate physician trainees at the level of behavior. Back et al. [13] conducted residential communication skills workshop (Oncotalk) designed for medical oncology fellows, which evaluated the efficacy of Oncotalk in changing observable communication behaviors. The results of the workshop revealed that the participants acquired substantial skills in giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care [13].

Many countries in the Middle East still lack palliative care services and only a few medical and nursing schools have incorporated palliative care into their curriculum. Those that did, however, allocate insufficient time to it. Moreover, residency programs in oncology, medicine and pediatrics do not include palliative care in their core curriculum, and residents and fellows are seldom examined in it.

In the last decade, many more people in the region have heard about palliative care, and come to expect it to be available and accessible when they, or a loved one, need it. Further, more and more governments in the Middle East are acknowledging the need for nationwide palliative care services. Professionals, health administrators, policymakers and the public at large came to recognize that cancer patients become increasingly frail and dependent with a spectrum of suffering extending over months or years before they die. Their number is increasing and will inexorably increase with the aging of the population in the region. Of importance, it has come to be recognized that 90% of these people will (and should) remain under the care of their general practitioners/ family physicians; and only if their suffering is of such severity, complexity or rarity that their physicians cannot be expected to look after then, will a specialist’s expertise be needed [14]. It follows, therefore, that undergraduate medical and nursing students and even more so residents and fellows need to learn about palliative care [15]. Palliative medicine requires knowledge, compassion, sensitivity and humility and those who teach or train in this field must have those talents, and must know how to use appropriate teaching and tutorial techniques. Such mentors are now found in palliative care departments in hospitals, hospices and international organizations such as ASCO and ONS. We have become aware that palliative care is more than an exercise in clinical pharmacology, it encompasses psychosocial and spiritual aspects of the patient’s life (so often neglected both in undergraduate study and subsequent specialist training), and the suffering and needs of caring families [14].

Dr. Derek Doyle citing a colleague said: “We must ensure that never again will young men and women enter our noble profession unable to care for those they cannot cure, not knowing how to listen, not being ready to learn from nurses, and not sensitive to their patients’ greatest needs” [14].

In designing multinational training courses in the Middle East, ASCO and MECC systematically took into account, and included these specific components:

* Palliative care definitions

* Pain management

* Management of other physical symptoms

* Neuropsychological symptoms

* Patient/family perspectives

* Clinical communication skills

* Ethics

We have recognized the advantage of conducting multiprofessional training courses involving physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists and spiritual leaders, thereby facilitating cooperation. Furthermore, active rather than passive techniques are prioritized through discussions in small groups, role play and problembased learning.

The issue of training in palliative care has become an urgent one in the Middle East as most cancer is diagnosed at late stages of the disease, making palliative care an immediate need. For this reason, international organizations such as MECC, ASCO and ONS often see palliative care as an entry point in setting up ongoing regional professional training courses, as in a way these courses constitute an avant-garde palliative care. These initiatives which were in part supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), put palliative care on the radar screen in the region.

The few palliative care services in Middle Eastern countries are usually inaccessible to poor, rural populations. Hence, there is a need for a public health approach that is tailored to local conditions in the individual countries. Moreover, at each level of the health care system- in dispensaries and health centers in the community, and in district regional and specialized hospitals in capitals- there is a need to establish palliative care services while ensuring high quality care. First and foremost, such services require trained personnel including nurses, especially in the primary health care settings. Therefore, education and training are a must, as they facilitate convincing professionals and the public that pain and suffering are not necessarily characteristics of cancer. This task will take more years of educational endeavor, as the cancer-associated stigma is one of the principal barriers to effective action in bringing palliative care into the mainstream of cancer control in a good number of countries in the region. Where a disease is highly stigmatized, many individuals avoid seeking treatment and other services. Investing in educational programs is perhaps the most effective strategy for dispelling the stigma associated with cancer and its treatment with opioid and psychological approaches.

Palliative Care Workshop in Muscat, 2013: Course Objectives

On February 10-13, 2013 ASCO jointly with MECC and the Omani Cancer Association (OCA), held a palliative care workshop in Muscat, the Sultanate of Oman. 213 attendees took part in the workshop, a portion of the over 600 participants attending a week-long oncology learning program. The purpose of that workshop was to teach the best practices in palliative care with a focus on the elderly population.

The organizers aimed at heightening the attendees’ understanding of palliative care in the context of the elderly population. Learning objectives were:

• To enhance knowledge and practice of cancer management and palliative and supportive care in the older population in the region.

• To learn skills in the assessment of geriatric patients.

• To create a forum for participants to network and learn from each other.

• To improve the ability to communicate with patients and their families about cancer, treatment, and end of life care.

Evaluation plan overview

Evaluation plan steps:

On-site-course evaluation to gauge attendee opinions about what was learned at the course and intentions to change practice: Attendees completed an evaluation form at the end of the course that asked about how beneficial the course was in increasing their knowledge; intent to make changes to their work based on what was learned; selfassessment about progress in the course learning objectives.

Survey for attendees to report actual changes made as a result of attending the course: Ten months after the course, attendees will be asked to complete a survey about actual changes made; actions taken to advocate for palliative care services; actual progress made towards achieving program objectives. The results of the survey will be analyzed and published (Table 1).

| Multiple Choice Answer Table | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree or strongly agree | Disagree | Neutral | No Response | ||

| 1. | I am confident that I will make changes to my work as a result of what I’ve learned at this course. | 86% | 1% | 9% | 4% |

| 2. | I learned skills to evaluate, assess, and develop therapeutic options for geriatric patients. | 83% | 1% | 10% | 6% |

| 4. | I learned skills to provide quality palliative care to geriatric patients at the end of life. | 85% | 1% | 7% | 7% |

| 5. | I feel more confident in my ability to communicate with geriatric patients and their families about what to expect during the end of life. | 81% | 1% | 11% | 7% |

| 6. | The course enhanced my understanding of the appropriate use of morphine. | 84% | 2% | 11% | 3% |

| 7. | I better understand how to manage mental illness in elderly patients. | 73% | 2% | 17% | 8% |

| 8. | I learned general principles of symptom management and plan to implement them at my institution / hospital. | 86% | 1% | 8% | 5% |

| 9. | I better understand methods and medications to control pain and can communicate their benefits / disadvantages with patients. | 81% | 1% | 15% | 3% |

| 10. | I learned what I had hoped and expected to learn at this course. | 86% | 0% | 11% | 3% |

| 11. | The course materials and information presented are useful and relevant to me. | 89% | 1% | 7% | 3% |

| 12. | Presentations were based on the best available evidence | 88% | 0% | 8% | 4% |

| 13. | Presentations were free from commercial influence or bias. | 87% | 0% | 10% | 3% |

| 14. | Sufficient time was allowed for networking and dialogue among participants and faculty. | 87% | 2% | 3% | 4% |

| 15. | Overall, the quality of the meeting was of a high standard. | 93% | 1% | 3% | 3% |

| 16. | Overall, the speakers were knowledgeable and presented the information clearly. | 93% | 0% | 4% | 3% |

| 17. | I would recommend this meeting to a colleague. | 94% | 0% | 3% | 3% |

Table 1: Respondents were asked to indicate the level of agreement to the following statements.

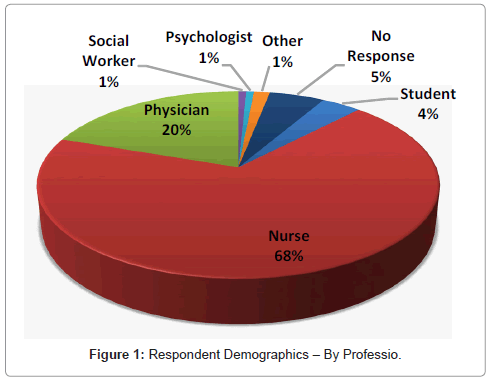

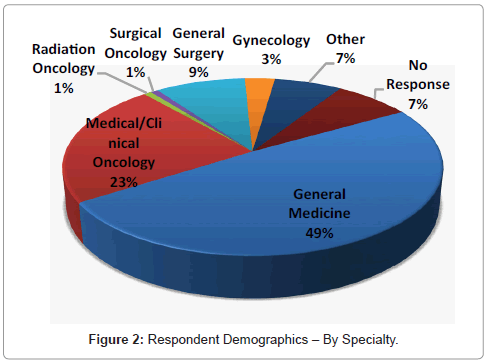

Attendee demographics: There were 213 attendees in the Palliative Care Workshop. Of these, 132 completed the evaluation form (61%).

Demographics: Professions and specialties: Based on the information submitted, the attendees were a highly diverse group, representing a large range of interests and experiences. The largest group of respondents consisted of nurses.

Demographics: Years in medical practice: When asked about years of experience working in medical practices, the average respondent had spent 14 years, the maximum number of years spent was 40, and the minimum was 2 years. Several respondents did not provide a response.

Demographics: Percentage of time working in cancer: Attendees were asked to indicate the percentage of their professional time spent on cancer related issues. Several respondents did not provide a response. Twenty-eight percent of respondents spent over half their time working with patients who have cancer. 61% spent less than half their time working with patients who have cancer.

Evaluation results: Overall intention to change practice: Eighty percent of respondents indicated they will make changes in their work based on information learned during the course. They plan to make some of the following changes:

• Improve communication with patient and family.

• Better pain management of patient.

• Share knowledge learned with colleagues; give lecture.

• Start a palliative care team at institution.

• Better assessment of patient.

• Increase community awareness about palliative care

• Begin palliative care early.

• Participate in palliative care educational events.

• Research

• Teamwork/interdisciplinary team

Forty-nine percent of respondents indicated they anticipated obstacles to making practice changes. The following are some of the obstacles indicated:

• Lack of administrative support.

• Insufficient staff.

• Insufficient resources: funding, facilities, medication…

• Insufficient time

• Communication barriers due to: language, culture, stigma…

• Insufficient staff training

Evaluation results: By course objective:

To enhance knowledge and practice of cancer management and palliative and supportive care in the older population in the region

• Eighty-nine percent of respondents reported learning skills to provide quality palliative care to geriatric patients at the end of life.

• Eighty-four percent of respondents reported enhancing their understanding of the appropriate use of morphine

• Seventy-three percent of respondents reported better understanding of how to manage mental illness in elderly patients.

• Eighty percent of respondents reported learning general principles of symptom management and plan to implement them at their institution/hospital.

• Eighty-one percent reported better understanding of methods and medications to control pain and to communicate their benefits / disadvantages to patients.

• Twenty four respondents indicated in an open ended question that they would make improvements how they manage pain in their patients as a result of what they learned in the workshop.

To learn skills in assessment of geriatric patients

• Eighty-three percent of respondents reported learning skills to evaluate, assess, and develop therapeutic options for geriatric patients.

To create a forum for participants to network and learn from each other

• Eighty-seven percent of respondents reported sufficient time was allowed for networking and dialogue among participants and faculty.

Increase ability to communicate with patients and their families about cancer, treatment, and end- of- life care

• Eighty-one percent of respondents reported confidence in their ability to communicate with geriatric patients and their families about what to expect during the end- of- life stage.

• Twenty-nine respondents indicated in an open answer question that they intend to incorporate new and improved communication skills in their work with patients and families as a result of what they learned at the workshop.

Summary and Conclusions

• Based on the evaluation information we have gathered the palliative care workshop was a success in meeting course objectives.

• The two most important things participants learned at the workshop were psychological aspects of delivering palliative care to patients with stress, anxiety, and pain, and more generally the role of palliative care in cancer management.

• A high percentages of respondents reported learning new knowledge and skills in areas prioritized by the learning objectives. How this translates into practice will be assessed in the follow up survey.

• Open-ended questions on intention to change practice generated the intention of significant numbers of attendees to work more closely with colleagues and to change practices in palliative care topics with a focus on patient communication and pain management. These topic areas were course objectives.

• The two main challenges for making changes based on knowledge gained were lack of administrative support and lack of staff.

• Ninety-four percent of evaluation respondents replied they would recommend this meeting to a colleague (Figures 1 and 2).

• More sessions and topics specifically for nurses, and further training in pain management for the cancer patient, were two areas for future training cited by numerous respondents.

• The impact assessments will be distributed to participants approximately 10 months after the end of the course. Results from the impact assessments, coupled with results from the post-course evaluations, will help assess the potential of similar events in the region to stimulate change over the long term.

Open- ended questions and responses

What was the most important thing you learned at this course?

1. Psychological focus in palliative care to treat patients with: depression, stress, anxiety, pain (24).

2. Importance of palliative care in cancer management (22).

3. Methods of improving the quality of life (19).

4. Integrating palliative care into cancer management in the Middle East and Oman (18).

5. Importance of aspect of pain management in palliative care (16).

6. Patient communication and communication with family members (15).

7. Interdisciplinary collaboration during cancer management, especially the role of nurses in palliative care (15).

8. Developed new skills (11).

9. Use of opiates in pain management (10).

Based on your participation in this course, is there anything that you will do differently in your work? If yes, what changes will you make?

1. Improve communication with patient and family (29).

2. Better pain management of patient (24).

3. Provide psychological support for patient (18).

4. Share knowledge learned with colleagues; give lecture (16).

5. Start a palliative care team at institution (10).

Is there anything that would prevent or limit you from making the change(s) you listed above? Please explain

1. Lack of administrative support (33).

2. Insufficient staff (24).

3. Insufficient resources: funding, facilities, medication… (14).

4. Insufficient time (12).

What additional educational topics would be useful to you, to deepen your knowledge and abilities in providing palliative care?

1. Pain management in cancer management (20).

2. Communication with patient and family members (11).

3. Psychological needs of patient: anxiety, depression, stress management… (10).

Other comments or suggestions for future courses?

1. Provide more sections specific to nurses or a separate course for nurses (12).

2. Increase frequency of conference (12).

3. Time (11).

• Longer conference.

• Shorter days.

• More group discussion.

• Longer speaker presentations.

• Keep to time schedule more closely.

4. Include additional topics: nutrition, stress management, pain management, communication, leadership, patients with HIV… (9).

How do you intend to advocate for palliative care services in your country and/or institution?

1. Share what was learned with colleagues (27).

2. Increase public awareness about palliative care (21).

3. Establish a palliative care program and/or curriculum at institution (17).

4. Promote the benefits of palliative care (16).

Palliative Care Workshop in Ankara, 2012

Last year (April 2012) ASCO jointly with MECC and the Turkish Institute of Public Health at the Ministry of Health, organized a palliative care workshop in Ankara, Turkey attended by 79 participants. The workshop focused on: “Approaches for oncology integrated palliative care in Middle Eastern countries”. Of the attendees 51 completed similar evaluation forms (64%), the responses obtained were strikingly similar to those obtained this year stressing the importance of learning skills to advocate for palliative care services, and understanding the role of the individual Care Givers. When asked what additional educational topics would be useful to deepen the knowledge and abilities to provide palliative care; the most common responses were:

1. Psychological and/or psychosocial care.

2. Symptom management.

3. Palliative care policy.

When asked “how do you intend to advocate for palliative care services in your country and/or institution”, the most common response was through education.

Discussion

The responses and observations gleaned from the two ASCOMECC workshops in the Middle East described above provide further support for the notion that additional efforts are needed to improve the management of cancer-related physical and emotional symptoms by means of ongoing training sessions for all care givers, in particular physicians and nurses, as has been recently advocated [16,17]. Thus, more work is needed, perhaps in medical and nursing schools, but certainly in residency and fellowship programs [18]. Oncologists can help patients understand their condition by giving personalized information. Truthful conversations that acknowledge death help patients understand their curability. Oncologists, however, need help in breaking bad news [19]. Additionally, in most Middle Eastern countries, physicians learn only about opiates’ side effects, not their potential benefits and modern principles of pain relief. Significantly, palliative care still is not taught to medical students in 80% of the world [20]. Hence, one of the key challenges in the Middle East is developing human capacity and training [21-24].

It is recommended that palliative care education and training begin as early as possible in graduate school, although it is not too late for practicing health care professionals to pursue this specific training within their areas of interest. Members of multidisciplinary teams should also obtain updated training in the various aspects of palliative care, based on their respective scope of services [25]. That is what the joint effort of ASCO, ONS and MECC is trying to do.

References

- Colleau SM (1996) Physician education in palliative medicine: a vehicle to change the culture of pain management. HIV/AIDS Cancer Pain Release, WHO Pain & Palliative Care Com 9: 3.

- Silbermann M (2009) Leading the way in pain control: A MECC-ONS course for oncology nurses. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 31: 605-618.

- Silbermann M (2010) Endeavors to improve palliative care services to cancer patients in Middle Eastern countries. ASCO Educational Book 217-221.

- Silbermann M (2011) MECC workshop on cancer pain, suffering and the complexities of evidence-based intervention in cancer care. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 33: S81-S161.

- Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Abdel Rahman H, Ashraf S, Ben Arush M, et al. (2012) Pediatric Palliative Care in the Middle East. In: Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives. Springer Science 127-159.

- Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Daher M, Nestoros S, Pitsillides B, et al. (2012) Palliative cancer care in Middle Eastern countries: accomplishments and challenges. Ann Oncol 23: 15-28.

- Silbermann M, Al-Zadjali M (2013) Nurses paving the way to improving palliative care services in the Middle East. J Palliative Care Med 3: e125.

- Block SD, Bernier GM, Crawley LM, Farber S, Kuhl D, et al. (1998) Incorporating palliative care into primary care education. National Consensus Conference on Medical Education for Care Near the End of Life. J Gen Intern Med 13: 768-773.

- Tresolini CP, Pew-Fetzer Task Force (1994) Health Professions Education and Relationship-Centered Care. San Francisco, CA. Pew Health Professions Commission.

- Fineberg IC, Wenger NS, Forrow L (2004) Interdisciplinary education: evaluation of a palliative care training intervention for pre-professionals. Acad Med 79: 769-776.

- Kolarik RC, Walker G, Arnold RM (2006) Pediatric resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. Pediatrics 117: 1949-1954.

- Mohanti BK, Bansal M, Gairola M, Sharma D (2001) Palliative care education and training during residency: a survey among residents at a tertiary care hospital. Natl Med J India 14: 102-104.

- Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA, Alexander SC, et al. (2007) Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med 167: 453-460.

- Doyle D (2007) Curriculum in palliative care for undergraduate medical education. Recommendations of the European Association for Palliative Care. Report of the EAPC Task Force on Medical Education.

- Charalambous H, Silbermann M (2012) Clinically based palliative care training is needed urgently for all oncologists. J Clin Oncol 30: 4042-4043.

- Breuer B, Fleishman SB, Cruciani RA, Portenoy RK (2011) Medical oncologists' attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: a national survey. J Clin Oncol 29: 4769-4775.

- Von Roenn JH, von Gunten C (2011) The care people need and the education of physicians. J Clin Oncol 29: 4742-4743.

- Stockler MR, Wilcken NR (2012) Why is management of cancer pain still a problem? J Clin Oncol 30: 1907-1908.

- Smith TJ, Longo DL (2012) Talking with patients about dying. N Engl J Med 367: 1651-1652.

- Lamas D, Rosenbaum L (2012) Painful inequities--palliative care in developing countries. N Engl J Med 366: 19201.

- Brown R, Kerr K, Haoudi A, Darzi A (2012) Tackling cancer burden in the Middle East: Qatar as an example. Lancet Oncol 13: e501-508.

- Abu-Zeinah GF, Al-Kindi SG, Massan AA (2012) Middle East experience in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 30: 94-99.

- Qidwai W, Ashfaq T, Khoja TAM, Rawaf S, Kurashi N, et al. (2012) Access to person-centered care: A perspective on status, barriers, opportunities and challenges from the Eastern Mediterranean region. World Family Medicine J 10: 4-13.

- Boumelha J (2008) Tackling cancer in the Middle East. CANCER WORLD.

- Jazieh AR (2013) Capacity building in palliative care. J Palliative Care Med 3: 138.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14592

- [From(publication date):

specialissue-2013 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10028

- PDF downloads : 4564