Research Article Open Access

Palliative Care: Supporting Adult Cancer Patients in Ibadan, Nigeria

Soyannwo Olaitan*, Aikomo Oladayo and Maboreje OloladeHospice and Palliative Care Unit, University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Olaitan S

Hospice and Palliative Care Unit

University College Hospital (UCH)

Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria

Tel: +234 8023238326

E-mail: folait2001@yahoo.com

Received date: Mar 29, 2016; Accepted date: May 04, 2016; Published date: May 07, 2016

Citation: Olaitan S, Oladayo A, Ololade M (2016) Palliative Care: Supporting Adult Cancer Patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Palliat Care Med 6:258. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000258

Copyright: © 2016 Olaitan S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Over 70% of adult cancer patients present late to hospital in Nigeria with devastating consequences. Yet, structured palliative care is only an emerging service in this country with population of over 160 million. Objective: To describe activities of the Ibadan palliative care group and review one year holistic care programme offered by the team to support patients and their families. Methodology: A retrospective study reviewed treatment notes of patients that were enrolled from January to December 2013. Information retrieved included bio-data, stage of cancer, presenting complaints, palliative care issues identified, services rendered, days on programme, outcome and challenges. Results: Structured Palliative care service consisting of hospital based care, day care and home based care commenced in 2008, being the first of such in Nigeria. The service was based at the University College Hospital, Ibadan and run in collaboration with Centre for Palliative care Nigeria, a non-governmental organization. 189 patients were seen within the year and 121 (64%) were adults with advanced cancer. There were 44 (36.4%) male and 77 (63.6%) female with age range 21 to 91 years. 89 (73.6%) had moderate to severe pain. Psychosocial issues were present in 73% and spiritual issues in 17.4%. Services that were offered despite major challenges of late referral and financial constraints provided pain and symptom control, counselling, education for patients and family, financial and spiritual support thus improving quality of life Conclusion: Patients and their families found that palliative care provided relief to pain and suffering. More can be achieved through training of more health professionals, increased public awareness of the services and government support.

Keywords

Adult cancer; Cancer care; Palliative care

Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of adult deaths and it accounted for 7.6 million deaths worldwide in 2008. It features among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with approximately 14 million new cases and 8.2 million cancer related deaths in 2012 [1]. The recent new cases of cancer diagnosed in Nigeria, a country with estimated population of 166.6 million were 102,100 per year and 71,600 deaths per year [2]. The projected new cases of cancer for the world will stand at 27 million, while that of Africa will stand at 1.52 million by 2030 [3-5]. Currently, over 70% of cancer patients in Africa present with advanced cancer in hospital [6]. In Nigeria, reasons for late presentation include late recognition of initial symptoms due to lack of knowledge, search for alternate treatment and cure, inappropriate advice, poverty and fear of hospitals. Such patients at presentation have severe pain with several distressing symptoms requiring palliative care.

Palliative care as defined by WHO is “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual [7]. It offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death. Using a team approach, palliative care addresses the needs of patients and their families as they develop, including bereavement counselling if necessary. Palliative care is offered in conjunction with curative intent and can take place in any setting [8,9]. Palliative care is a new addition to Nigeria health care system as development commenced only in 1991[10]. The University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan is a foremost cancer referral centre in Nigeria. It is the first tertiary hospital to start structured palliative care services. The services commenced in 2008 as a collaborative effort between the hospital and the Centre for Palliative Care Nigeria (CPCN) which is a non-profit organization. The Hospice and palliative centre is a stand-alone day care facility situated within the hospital. It is opened for services between 8 am and 4 pm on weekdays with emergency cover by the palliative care team on call duty basis through telephone and the emergency department of the hospital. Patients are referred from within the hospital wards, out-patient clinics and other health facilities. Services provided by the trained palliative care team (including nurses, doctors and social workers) are through outpatient care, co-management of in-patients, home based care following discharge for those patients within the catchment area [11].

The purpose of this study is to present a review of adult cancer patients who received palliative care in the Hospice and Palliative Care Unit, UCH within the period of 12 months, review the outcome of the services rendered, identify the challenges and to proffer way forward. This is the first of such a report from Nigeria and West Africa.

Material and Methods

This is a retrospective review of routine care of all adult cancer patients that had palliative care services in the day care hospice centre from January 2013 to December 2013. All case records of patients were retrieved to collect bio-data, stage of cancer, presenting complaints, palliative care issues identified, services rendered, days on programme, outcome and challenges. The results were analysed in a simple descriptive format and presented.

Results

In the period under review, a total of 189 patients were enrolled for palliative care at the Unit out of which 121(64.0%) were adult cancer patients. The ratio of the Male to Female is 1:1.8. The age range was 21- 91 years; mean age was 59 ± 4. The days on programme range from 5 – 224 days. Age distribution is as shown in Figure 1.

Most patients (67%) were in the age group 54 to 71 years. Table 1 shows the spectrum of cancers the patients were being managed for with the topmost four being breast cancer (23.9%), gastrointestinal cancers (19.8%), prostate cancer (14%) and cervical cancer (11.6%). Most (96.4%) had advanced cancer (stage 4) while the remaining 3.6% were of cancer stage 3.

| Diagnosis | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | 29 | 23.97 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 24 | 19.83 |

| Prostatic cancer | 17 | 14.05 |

| Cervical cancer | 14 | 11.57 |

| Other gynae-oncological cancer | 12 | 9.92 |

| Head/Neck cancer | 11 | 9.09 |

| Blood cancer | 4 | 3.31 |

| Lung cancer | 4 | 3.31 |

| Other urological cancer | 3 | 2.48 |

| Osteosarcoma | 2 | 1.65 |

| Peripheral nerve sheath tumor | 1 | 0.83 |

| Total | 121 | 100.01 |

Table 1: Cancer diagnosis.

Sixty- seven patients (53%) were Muslims and 54 (45%) of Christian religious affiliation. Palliative care Services were rendered for all patients when on hospital admission, at the Day Hospice on outpatient basis and at home. Fourteen family conferences were organised when required and twelve bereavement visits carried out.

Eighty- nine (73.6%) patients presented with moderate to severe pain - score 4 to 10 out of 10 using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) as shown in Table 2. Nineteen (21%) patients had multiple pain sites (2 -3). The scoring was done by 79(89%) patients while 10(11%) were by relatives due to the unconscious state of the patients.

| Pain Score(NRS) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 32 | 26.4 |

| 1-3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4-7 | 62 | 51.2 |

| 8-10 | 27 | 22.4 |

| Total | 121 | 100.0 |

Table 2: Pain score.

Fifty-four (61%) of patients that had moderate to severe pain were treated with a combination of oral liquid morphine, diclofenac and amitriptyline. Nineteen (21%) had dihydrocodeine and amitriptyline. Ten (11%) were administered a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen while six (7%) patients were given dihydrocodeine and diclofenac for pain control.

Patients also complained of other multiple distressing symptoms including weight loss, anorexia, nausea, vomiting and cough as shown in Table 3. Patients self-reported responses as recorded in the case file showed that eighty patients (89%) reported satisfactory pain control.

| Other symptoms | N |

|---|---|

| Weight loss | 82 |

| Anorexia | 43 |

| Nausea | 28 |

| Drymouth | 22 |

| Vomiting | 20 |

| Cough | 18 |

Table 3: Other distressing symptoms.

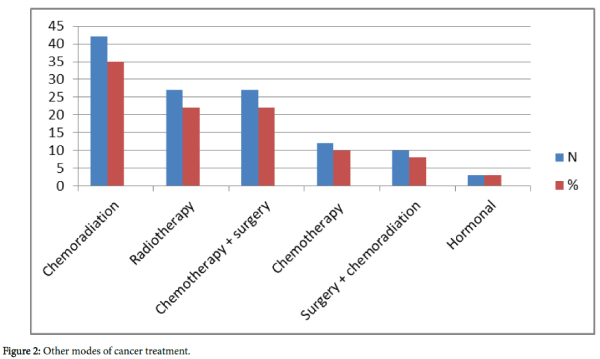

Psychosocial issues were identified by the palliative care team in 88 patients (73%) and included loss of job, severe financial constraint, loss of body parts, disfigurement and feeling of being a burden on family members or carers. Spiritual Issues encountered in 21 (17%) patients were feelings of guilt, loss of meaning of life and the question “why me? “while 12(10%) patients were unconscious so psychosocial and spiritual assessments could not be done (Table 4) Other modes of cancer treatment undertaken by the patients are as shown in Figure 2. At the end of the review period, eighty-two (68%) of the patients were dead while.

| Palliative care issues | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial | 88 | 73 |

| Spiritual | 21 | 17 |

| Unconscious | 12 | 10 |

| Total | 121 | 100 |

Table 4: Other palliative care issues.

Discussion

In many developing countries, patients often present with far advanced malignant disease, of who up to 80% of people with cancer may be incurable at diagnosis [12]. In Nigeria, 60-70% of patients with cancer presents late [13] and is referred for palliative care as shown in this study. The common cancers in the country and low average life span are also reflected in this data. Advocacy for effective pain management and palliative care started in Nigeria in 1991 by a group of health care professionals drawn from different disciplines. Their first focus was to make opioid analgesics available for palliative care of cancer patients and collaboration with the University College Hospital Ibadan later led to establishment of the first palliative care Unit in a tertiary hospital [9].

In many developing countries like Nigeria, the prevalence of pain at time of cancer diagnosis is between 50% and 75% [6]. Adenipekun et al. [6] had earlier reported pain as major symptom in 70% of patients presenting with advanced cancers in the same hospital. Unresolved pain leads to poor quality of life in patients and distress for both patients and carers. Hence most patients were referred for effective pain management and continuum of care. Moderate to severe pain featured in all patients referred to the Unit as seventy per cent of the patients had pain scores of 4-7 while 27 (30%) had pain scores 8-10. Oral morphine, the only available strong opioid analgesic was used in conjunction with non-opioid analgesics and adjuvants to achieve pain control in most patients. WHO recommends opioid analgesics for the treatment of moderate to severe pain [14]. Morphine has no standard dose as the ideal dose is the one that relieves the pain. In Nigeria, Morphine powder is imported and reconstituted into liquid morphine at affordable cost for patients [15,16]. Morphine, given in increasing amounts, was found to be safe. It was administered until the pain is relieved without producing an “overdose,” as long as the side effects are tolerated. The use of other modalities as shown in Figure 2 also enhanced pain control and 80 (89.9%) of the patients that presented with pain had their pain satisfactorily controlled as per their verbal response.

Other symptoms the patients presented with apart from pain were weight loss, anorexia, nausea, vomiting and dry mouth. These are recognised problems in palliative care patients [17]. Continuum of care allows patients to benefit from supportive care including counselling even when other interventions like chemotherapy and radiotherapy are still applicable for disease control. However, financial constraint was a major handicap since health care payment is born out of pocket by patients. Services were rendered in the unit by a team of trained palliative care staff that include medical doctors, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, administrative staff and volunteers. Most of them are also volunteer members of the Non- governmental organization, Centre for Palliative Care, Nigeria (CPCN) that supported the Unit.

Funds and other donations from CPCN and other support groups were used to provide subsidised care for indigent patients. Such areas include essential investigations like full blood count, purchase of medications, while also supporting the transportation cost for the home based care service. Comfort packs containing essential daily needs like toiletries, materials for wound dressing and raw food items are given to identified indigent patients as needed. Furthermore, day care forum is organized for patients and their relatives for social interaction, opportunity to be attended to by the different health care personnel including occupational therapists, physiotherapist and a psycho-oncologist. A conducive environment is provided for the patients and carers to rest/sleep before or after their lunch. The contributions from volunteer and support groups are valuable in supporting such activities which are not catered for under government budgetary allocations. A hospital chaplaincy committee has also been set up to help with burning spiritual issues that are elicited by the palliative care members during conversations with the patient or their carers. Such support facilities and the strong religious beliefs of patients might have contributed to few serious spiritual issues identified in the patients under review.

The need for family conferences was found particularly necessary when patients and their family members have little or no insight into the gravity of the disease condition and management options. It is also important in polygamous setting where information sharing within members of the family is often restricted. Such meetings educate family members (spouses, children, next of kin as per patient’s records, main carers), harness support for patients and sometimes resolve family conflicts. Culturally, some children such as first child or first son are considered major decision makers for the family. They are invited to attend such family conferences even when they live in other countries. This may assist the patient in making advanced care directives and to put his or her home in order. Bereavement support in form of condolence telephone calls were routinely offered to all dead patients’ relations that could be reached. Some relations of patients who died at home required bereavement support in terms of death certification, mortuary and funeral arrangements.

At the end of the study period, only 24 (20%) patients were still alive and those lost to contact (12%) could also be dead. A patient is said to be lost to contact after continuous calling of their mobile contacts or that of their carers for three months without any response. Despite several sensitization and awareness programmes for health professionals in the hospital, many still view palliative care as ‘end of life care ‘and hence patients are referred to the Unit only when primary consultants feel ‘there is nothing else’ to offer in terms of curative intent rather than early referral for co-management. Also as reported in another study [18] many doctors still exhibit fear about morphine prescription and addiction. Hence, most patients are referred more specifically for pain management.

The several challenges facing effective pain relief in our practice are similar to those of other developing nations and include drug availability, lack of referrals, fears of misuse of potent narcotics/underprescribing, lack of public awareness (healthcare workers, policymakers/administrators, the public), cultural and religious beliefs [19], shortage of financial resources, limitations of healthcaredelivery systems and personnel, absence of national policies on cancer pain relief and palliative care, and legal restrictions on the use and availability of opioid analgesics. Many of these will be overcome as pain and palliative care education and service expands in the country with appropriate and adequate government policy and support.

Summary

The data from this review buttresses previous findings that cancer patients present late in hospital with a lot of pain. Palliative care services are essential for both patients and their families in order to reduce pain, suffering, provide useful information and support till end of life and beyond. This model of palliative care with affordable oral morphine catered for patients from tertiary to community level of health care. It can provide a simple way for future integration of palliative care into national cancer care and health plan care.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the pioneering role of the University College Hospital, Ibadan for establishing the first specialist palliative care service in Nigeria and the contributions of the staff and volunteer team.

References

- Cancer Statistics (2016) National cancer institute.

- Cancer Index (2015) Nigerian cancer organizations and resources.

- Globacan Cancer Fact Sheet (2008) Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide. International Agency for Cancer Research.

- Jemal A, Bray F, Forman D, O’Brien M, Ferlay J, et al. (2012) Cancer burden in Africa and opportunities for prevention. Cancer 118: 4372-4384.

- Omolara KA (2011) Feasible cancer control strategies for Nigeria: Mini-Review. Am J Trop Med Pub Health 1: 1-10.

- Adenipekun A, Onibokun A, Elumelu TN, Soyannwo OA (2005) Knowledge and attitudes of terminally ill patients and their family to palliative care and hospice services in Nigeria. Niger J ClinPract 8: 19-22.

- http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Cecilia S, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A (2002) Palliative care: The World Health Organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 24: 91-96.

- Soyannwo O (2013) Hospice and palliative care development in West Africa sub region: A review. African J. Anaesthesia and Int. care 13:10-13.

- OMoyeni NE, Soyannwo OA, Aikomo OO, Iken OF (2014) Home based palliative care for adult cancer patients in Ibadan-a three year review. Ecancermedicalscience 8: 490.

- Van Gurp J, Soyannwo O, Odebunmi K, Dania S, van Selm M, et al. (2015) Telemedicine's Potential to Support Good Dying in Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. PLoS One 10: e0126820.

- Spence D, Merriman A, BinagwahoA (2004) Palliative care in Africa and the Caribbean. PLoS Med 1: e5.

- Soyannwo OA (2009) Cancer pain – progress and ongoing issues in Africa. Pain Res Manag 14: 349.

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief: A guide to opioid availability.

- O'Brien M, Mwangi-Powell F, Adewole IF, Soyannwo O, Amandua J et al. (2013)Improving access to analgesic drugs for patients with cancer in sub Saharan Africa. Cancer control in Africa Series 5, Lancet Oncol14: e176-182

- Eyelade OR, Ajayi IO, Elumelu TN, Soyannwo OA, Akinyemi OA (2012) Oral morphine effectiveness in Nigerian patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 26: 24-29.

- Von Gutten CF (2005)Iterventions to manage symptoms at end of life. J Palliat Med 1:588-594.

- Onyeka TC (2011) Palliative Care in Enugu, Nigeria(2011): Challenges to a New Practice. Indian J Palliat Care 17:131-136.

- Soyannwo OA (2010) Pain management in Nigeria-challenges, gains and future prospects.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11986

- [From(publication date):

May-2016 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11023

- PDF downloads : 963