Research Article Open Access

Oral Health Perception in Institutionalized Elderly in Brazil: Psychosocial, Physical and Pain Aspects

Araújo Isabela Dantas Torres1, Cunha Myla Marilana Freire da1, Lima Kenio Costa de2, Nunes Vilani Medeiros de Araújo3 and Piuvezam Grasiela3*1School of Dentistry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Brazil

2Department of Dentistry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Brazil

3Department of Public Health, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Brazil

- *Corresponding Author:

- Grasiela Piuvezam

Av. Senador Salgado Filho

3000 – Lagoa Nova CEP:

59078-970 – Natal, RN, Brazil

Tel: +55 84 88684919

Fax: +55 84 33422275

E-mail: gpiuvezam@yahoo.com.br

Received Date: December 06, 2014; Accepted Date: February 23, 2015; Published Date: March 02, 2015

Citation: Araujo IDT, Cunha MMF, Lima KC, Nunes VMA, Piuvezam G (2015) Oral Health Perception in Institutionalized Elderly in Brazil: Psychosocial, Physical and Pain Aspects. J Oral Hyg Health 3:171. doi: 10.4172/2332-0702.1000171

Copyright: ©2015 Araújo, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Oral Hygiene & Health

Abstract

Objective: Identify self-rated oral health dimensions of institutionalized elderly in Brazil using the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), and seek associations with objective, subjective and behavioral conditions.

Methodology: Cross-sectional study based on a census of institutionalized elderly. A total of 1192 individuals, living in 36 long-stay institutions for the elderly (LSIE) were evaluated. Of these, 587 (49.2%) responded to the GOHAI. A questionnaire containing subjective and oral health behavior questions was applied and an epidemiological survey (WHO criteria) conducted.

Results: With regard to the psychosocial dimension, multiple regression analysis demonstrated that the variables absence and need for upper prosthesis remained significant. Variables for the physical dimension were presence of dental problems and CPI of 6 mm or more, while in the pain or discomfort dimension, it was opinion of teeth, gums or prosthesis.

Conclusions: A better understanding of GOHAI dimensions may increase knowledge of oral health conditions among institutionalized elderly in Brazil, thereby contributing to action planning, organization and monitoring of health services besides improved health and quality of life.

Keywords

Oral Health; Geriatrics; Nursing Homes; Institutionalization

Introduction

Brazil is in rapidly aging process and this fact can be understood by analyzing the Brazilian population pyramid. In this, the base - birth rate index - is becoming even narrow, although, the apex - population aging index - is becoming more extensive. Following this reasoning, statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO) show that in the period 1950-2025, the Brazilian population will increase by 15 times. This fact will lead Brazil to occupy the sixth place as the number of elderly, reaching about 32 million people over 60 years of age [1].

In this context, it’s important to target the general health of this population, and we should also emphasize oral health, because when neglected, will result in a decrease in self-esteem, nutrition, in other words, the quality of life in general [2]. For this importance to be given, it is necessary to pay greater attention to public policies related to this group. However, it’s essential to understand how the elderly perceive and evaluate their oral conditions, because this perception conditions the patient to seek professional aid.

Nevertheless, it’s unusual for people to identify oral health conditions as their only health problems when those issues are so advanced that they affect feeding ability, speaking, chewing, physical appearance, and social life, frequently producing pain and favoring depression [1-4]. Oral health expectations among the elderly could also be influenced by age, education level, socioeconomic situation, and social support [3].

Self-rated oral health is a multidimensional measure reflecting the subjective experience of individuals regarding their functional, social and psychological well-being [5]. It can be used as a general indicator of treatment needs or to estimate the effect of oral conditions on daily life [6]. Several factors may influence this perception, including socioeconomic characteristics [7-10], objective oral health conditions [7,11-13], cultural values, social welfare, previous experiences, psychological experiences, age, gender and belief that some pain and disabilities are natural of aging [1,4,14,15].

Identify the determinants of self-perceived oral health has proven crucial to understand people’s behavior and how they evaluate their needs [16,17]. In individual oral health care, knowing the individual’s outlook on their health is important to improve individuals’ adherence to healthy behavior conditions [18,19]. In the case of the elderly, this aspect becomes more relevant because the main reason for not seeking dental service is the fact that they don’t perceive a need for dental care [4,13,17].

There are indicators used to assess the subjective perspective which were originally called ‘socio-dental’ or ‘oral health status’ indicators. These terms have been replaced by the ‘Oral Health-Related Quality of Life’ (OHQoL), which emphasizes the impact of oral diseases and disorders on an individual’s functioning and psychosocial well-being [20].

Measures of oral health-related quality of life (OHQoL) are essential for epidemiological and clinical studies to provide accurate data for health promotion, disease prevention programs and allocation of health resources [20-24].

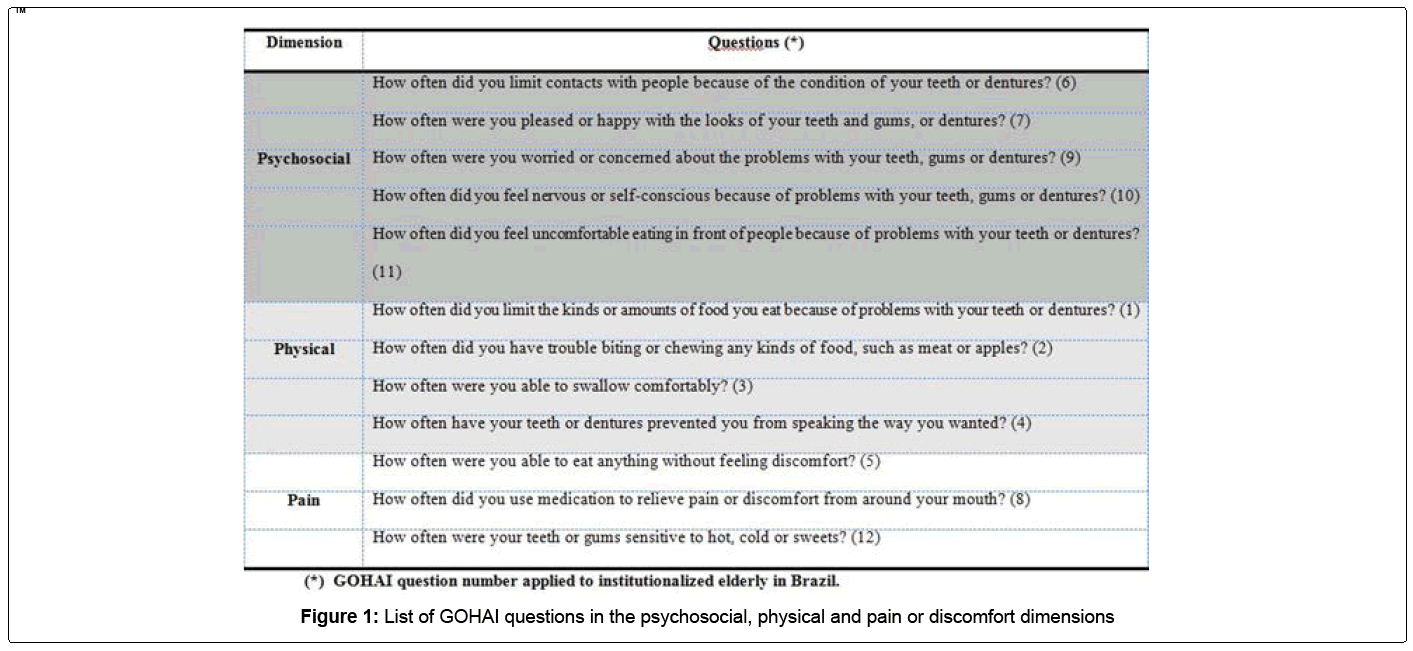

One of the most used instrument to estimate the OHQoL in elderly, is the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) [17,25], which was developed by Atchinson and Dolan in 1990 [1,4,14,20,21,24,26,27] to assess three dimensions of oral health as follows: physical functioning, social functioning and pain and discomfort [9,20,25,28].

Thus, the aim of the present study was to identify oral health-related psychosocial, physical and pain aspects in institutionalized elderly in Brazil, using the GOHAI. We also sought to determine associations between these aspects and objective and subjective health conditions, factors related to oral health behavior, individual characteristics and environmental factors.

Methodology

This is a cross-sectional study of institutionalized elderly in Brazil. It was carried out in 2007 and 2008 and based on the STROBE protocol [29]. A refinement in statistical analysis, which will bring important contributions in the process of interpretation that older people make about their oral health status, was made from the study of Piuvezam et al. [17]. This can help professionals as well as public policies improvement regarding the actions directed to this population in Brazil. The investigation was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (CEP-UFRN).

The study involved a census of institutionalized aged subjects from a random sample of 11 mid-sized and large municipalities in the five geographic regions of Brazil (North, Northeast, South, Southeast and Midwest). The following inclusion criteria were adopted:

1. Municipalities with 100 thousand inhabitants or more, according to the population projection list of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics for 2005

2. Municipalities with an elderly population greater than or equal to the median found in each geographic region.

The long-stay institutions for the elderly (LSIE) studied were private and philanthropic, and duly registered in their respective localities. In accordance with legal guidelines established in the National Policy for the Elderly [30], the sample was composed of individuals over the age of 60 years.

Aged participants presenting cognitive conditions, according to the clinical diagnosis of the LSIE physician, responded to the GOHAI [25]. The survey contains 12 questions scored between 1 and 3, that is, a range of 12 to 36 points for the overall index, characterizing the worst and best assessment, respectively. Responses are arranged on a scale of three response categories (always, at times or never) except for question 7 where these values were inverted to maintain the highest values for positive conditions in all questions. Thus, the higher the overall and individual dimension score the more favorable oral health-related quality of life [31]. The Brazilian version, validated by Silva [31], was used applied, using Cronbach’s alpha of 0.65 for dentulous and 0.76 for edentulous individuals.

The psychosocial dimension of GOHAI contains 5 questions involving concern about oral health, self-image, awareness of health, and oral-related social contact limitations, with a maximum score of 15 points. The physical dimension has 4 questions and encompasses aspects of eating, speaking and swallowing, with a maximum score of 12. The pain and discomfort dimension is associated to oral-dental status and contains 3 questions with a maximum score of 9 points. Questions related to each dimension are shown in Figure 1. In this study, GOHAI dimensions were considered dependent variables. Each dimension was categorized from the median values of positive or negative self-rated oral health conditions.

Individuals with cognitive conditions, as per the clinical diagnosis of the LSIE physician responded to a 4-question survey. Three of these were subjective and related to oral health conditions and 1 corresponded to oral health behavior, determined from data recorded at the last dental visit [16,32].

An epidemiological survey of oral health status was conducted using the DMFT, community periodontal index (CPI), periodontal loss of attachment (PLA) and prosthetic use and needs, according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [33]. Data were collected by 5 calibrated dentists, yielding inter and intra-examiner Kappa values between 0.71 and 0.89. Information was also gathered on sex, age and dependence of the elderly (dependent or independent), in accordance with to the clinical diagnosis made by the LSIE physician.

A questionnaire on geographic location, type of institution (philanthropic or private), Family Health Strategy (FHS) coverage and oral health activities (preventive or curative) was applied at each LSIE.

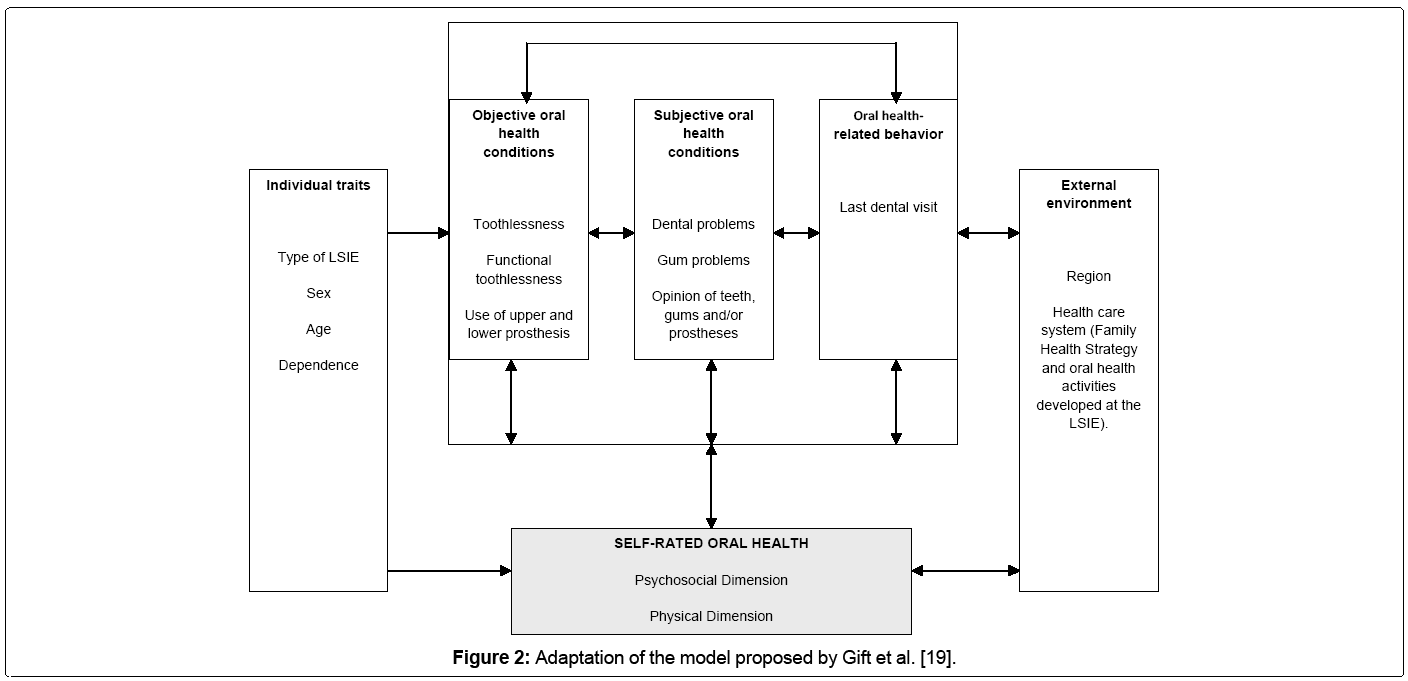

The inter-variable relationship was based on a theoretical model proposed by Gift, Atchinson and Durry [34], adapted for this study, presenting the interrelationship between the following 6 groups of variables: external environment, individual characteristics, oral health related behavior, objective and subjective oral health conditions and self-assessment of oral health (Figure 2).

Descriptive analysis was performed using absolute and relative frequencies of qualitative variables, as well as means, standard deviations, medians and quartiles for quantitative variables. Bivariate analysis used chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests to determine the association between variables. The magnitude of the effect of independent variables on the result was expressed by prevalence ratio (PR). A confidence level of 95% was adopted for all statistical tests. In order to analyze the independent effect of intervening variables on the outcome, multiple logistic analysis was performed using the forced entry model building procedure. All independent variables with p<0.20 in the association test were included. Model fit was determined by the Hosmer – Lemeshow test and analyses were conducted with Stata 10.0 software (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas).

Results

Total population for the 36 LSIE investigated was 1412 individuals. Of these, 1192 (84.4%) took part in the present study and 587 (49.2%) exhibited suitable cognitive capacity to respond to the GOHAI. Of these, 51.4% were men. Age ranged between 60 and 106 years and was categorized from the median, with mean age of 74.98 + 9.5. Most subjects live in philanthropic institutions and a minority are residents in facilities covered by the Family Health Strategy (FHS). Fewer than half receive any type of oral health care (Table 1).

| VARIABLES | n | % | VARIABLES | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual traits | Objective oral health conditions | ||||

| Sex | Toothlessness | ||||

| Male | 302 | 51.4 | Yes | 320 | 54.5 |

| Female | 285 | 48.6 | No | 267 | 45.5 |

| Dependence | Functionaltoothlessness | ||||

| Independent | 435 | 74.1 | Yes | 494 | 84.2 |

| Dependent | 152 | 25.9 | No | 93 | 15.8 |

| Categorizedage | Use of upperprosthesis | ||||

| 60 to 77 years | 359 | 61.2 | Yes | 269 | 45.8 |

| 78 yearsor more | 228 | 38.8 | No | 318 | 54.2 |

| Type of LSIE | Use of lowerprosthesis | ||||

| Private | 35 | 6 | Yes | 152 | 25.9 |

| Philanthropic | 552 | 94 | No | 435 | 74.1 |

| Oral HealthBehavior | |||||

| Last dental visit | Needforupperprosthesis | ||||

| Lessthan 1 yearago | 127 | 21.8 | Yes | 318 | 54.2 |

| More than 1 yearago | 456 | 77.7 | No | 269 | 45.8 |

| Subjective oral health conditions | |||||

| Dental problems | Needforlowerprosthesis | ||||

| No | 135 | 56.3 | Yes | 435 | 74.1 |

| Yes | 105 | 43.8 | No | 152 | 25.9 |

| Gingival problems | CPI | ||||

| No | 208 | 86.7 | Healthy | 22 | 3.7 |

| Yes | 32 | 13.3 | Bleeding | 04 | 0.7 |

| Opinion of teeth, gums, prosthesis | Calculus | 109 | 18.6 | ||

| Goodorexcellent | 351 | 63.1 | Pocket 4 to5 mm | 49 | 8.3 |

| Fair | 108 | 19.4 | Pocket ≥ 6 mm | 25 | 4.3 |

| Poor orverypoor | 97 | 17.4 | Excludedsextant | 378 | 64.4 |

| Externalenvironment | PLA | ||||

| Region | 0 to3 mm | 47 | 8.0 | ||

| South | 121 | 20.6 | 4 to5 mm | 57 | 9.7 |

| Southeast | 163 | 27.8 | 6 to8 mm | 58 | 9.9 |

| Midwest | 144 | 24.5 | 9 to11 mm | 31 | 5.3 |

| Northeast | 104 | 17.7 | 12 mmor more | 16 | 2.7 |

| North | 55 | 9.4 | Excludedsextant | 378 | 64.4 |

| FHS Coverage | |||||

| Yes | 152 | 25.9 | Categorized DMFT | ||

| No | 435 | 74.1 | DMFT 0 to 28.8 | 169 | 28.8 |

| Oral HealthActivity | DMFT> 28.9 | 418 | 71.2 | ||

| Yes | 236 | 40.2 | |||

| No | 351 | 59.8 | |||

Table 1: Characteristics of institutionalized elderly in Brazil, according to individual traits, objective and subjective conditions, oral health behavior, and external environment

Questionnaire data showed that only 20% of the elderly had consulted a professional within the previous year. Questions about the presence of dental and gum problems were responded to by 40.8% of subjects since the response condition was having at least one tooth. Answers related to opinion on teeth, gums or prostheses had 96.9% respondents and most reported a good or excellent opinion (Table 1).

Data regarding objective conditions of oral health indicate mean DMFT of 28.8 (± 5.5) (Table 1). Approximately half the individuals exhibited total tooth loss. When analyzed from the perspective of functional edentulism, the situation is even more serious, with 84.2% of the elderly presenting with 20 or more missing teeth.

Prosthetic rehabilitation was inadequate, as evidenced by the fact that around 54.2% and 74.1% of individuals used no type of upper and lower prosthesis, respectively. Among elderly participants using some type of upper or lower prosthesis, most wear total prostheses (40.9%) in the upper arch and 21.6% in the lower arch (Table 1).

With respect to the need for rehabilitation, results show that 45.8% do not require upper arch prostheses. Of those who do, 38.5% needed total prostheses and 14.1% some form of fixed or removable prosthesis. In the lower arch, 25.9% do not require prostheses and among those who do 257 individuals need total prostheses and 27.9% a fixed or removable prosthesis.

Periodontal conditions were analyzed using CPI and PLA indices. These were identified in sextants exhibiting the worst conditions for each individual. Thus, the most significant values for periodontal infirmities demonstrated that 18.6% exhibited calculus according to CPI criteria. And in relation to PLA results it was found that 10.1% displayed attachment loss of 4 to 5 mm. For bivariate and multivariate analysis, these variables were characterized for CPI in the absence of pockets for the healthy, bleeding and calculus categories and the presence of pockets for the others, as well as losses between 0 and 5 mm and 6 mm or more for the PLA variable.

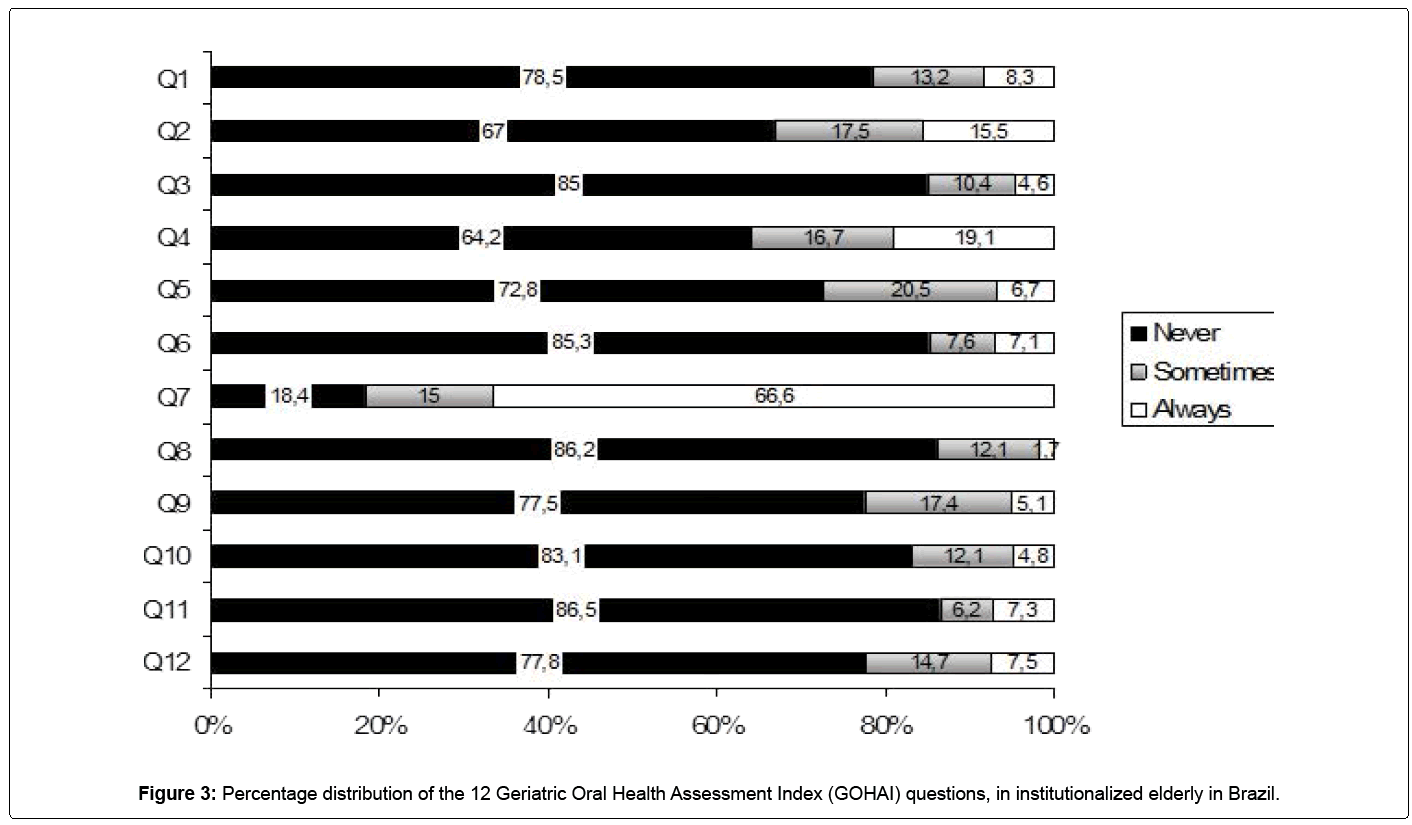

In relation to the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), Figure 3 shows that elderly subjects evaluated their oral health conditions as positive for most questions. Bivariate and multivariate analyses considered psychosocial, physical and pain dimensions as dependent variables. Results are shown in Tables 2-4. Prior to multivariate analysis, collinearity was sought among all variables considered for the model, using the tolerance test and VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values. No multicollinearity was detected.

| VARIABLES | NSR (%)* | PR cr | 95% CI | pa | PR adjust | 95% CI | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependence | 63.8 | 1.061 | 1.094-2.343 | 0.015 | 1.104 | 0.491-2.483 | 0.811 |

| Presence of dental problems | 76.2 | 2.885 | 0.198-0.608 | <0.001 | 1.858 | 0.873-3.952 | 0.108 |

| Opinion about teeth, gums and prótesis | |||||||

| Goodorexcellent | 42.5 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| Fair | 74.1 | 3.873 | 2.398-6.257 | <0.001 | 2.178 | 0.644-7.366 | 0.210 |

| Poor orverypoor | 83.5 | 6.863 | 3.856-12.21 | <0.001 | 8.799 | 2.773-27.92 | <0.001 |

| Toothlessness | 51.9 | 0.732 | 0.527-1.017 | 0.062 | 13 | 0 | 0.999 |

| Upperprosthesisabsent | 59.1 | 1.393 | 1.004-1.933 | 0.047 | 2.127 | 0.199-22.68 | 0.011 |

| Lowerprosthesisabsent | 59.5 | 1.918 | 1.320-2.786 | 0.001 | 0.935 | 0.160-5.469 | 0.941 |

| Needforupperprosthesis | 59.8 | 1.500 | 1.08-2.083 | 0.015 | 19.63 | 1.969-195.7 | 0.011 |

| Needforlowerprosthesis | 59.5 | 1.918 | 1.320-2.786 | 0.001 | 0.680 | 0.140-3.294 | 0.632 |

| PLA 6mm or more | 58.1 | 0.683 | 0.390-1.197 | 0.182 | 0.799 | 0.401-1.592 | 0.523 |

| DMFT ≥ 28.9 | 53.1 | 0.726 | 0.504-1.044 | 0.084 | 0.695 | 0.276-1.748 | 0.439 |

Table 2: Multivariate analysis of the Psychosocial Dimension of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index in institutionalized elderly in Brazil

| VARIABLES | NSR (%)* | PR cr | 95% CI | pa | PR adjust | 95% CI | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 62.6 | 1.443 | 1.038-2.006 | 0.029 | 0.763 | 0.361-1.613 | 0.479 |

| Dependence | 67.1 | 1.658 | 1.125-2.442 | 0.010 | 1.506 | 0.665-2.414 | 0.326 |

| Dental visit more than 1 year | 56.8 | 1.339 | 0.892-2.011 | 0.158 | 0.517 | 0.246-1.087 | 0.082 |

| Presence of dental problems | 74.3 | 3.505 | 0.164-0.496 | <0.001 | 2.113 | 1.005-4.442 | 0.048 |

| Opinion of teeth, gums and prosthesis | |||||||

| Goodorexcellent | 47 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| Fair | 72.2 | 2.931 | 1.831-4.691 | <0.001 | 3.169 | 1.377-7.294 | 0.007 |

| Poor orvery por | 82.5 | 5.305 | 3.019-9.323 | <0.001 | 9.440 | 3.165-28.15 | <0.001 |

| Upperprosthesisabsent | 60.7 | 1.243 | 0.895-1.728 | 0.194 | 0.515 | 0.87-3.043 | 0.464 |

| Lowerprosthesisabsent | 61.8 | 1.754 | 1.208-2.545 | 0.003 | 3.867 | 0.666-22.46 | 0.132 |

| Needforupper prótesis | 60.7 | 1.257 | 0.904-1.748 | 0.174 | 1.149 | 0.218-6.059 | 0.870 |

| Needforlower prótesis | 61.8 | 1.754 | 1.208-2.545 | 0.003 | 0.431 | 0.90-22.056 | 0.291 |

| PLA 6mm or more | 63.8 | 1.698 | 0.979-2.945 | 0.059 | 2.095 | 1.028-4.269 | 0.042 |

* NSR (%): Negative self-rating in percentage values; p< 0.05 were considered significant for the statistical tests; PR cr – crude prevalence ratio; PR adjust – adjusted prevalence ratio; CI – 95% confidence interval; Hosmer and Lemeshow test = 0.977; a – Chi-square test

Table 3: Multivariate analysis of the Physical Dimension of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index in institutionalized elderly in Brazil.

| VARIABLES | NSR (%)* | PR cr | 95% CI | pa | PR adjust | 95% CI | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependence | 51.3 | 1.372 | 0.947-1.987 | 0.094 | 1.322 | 0.653-2.675 | 0.438 |

| Age≥78 years | 42.1 | 1.251 | 0.895-1.748 | 0.190 | 1.045 | 0.525-2.080 | 0.900 |

| Dental visit more than 1 year | 43.6 | 1.442 | 0.972-2.140 | 0.068 | 0.527 | 0.271-1.026 | 0.059 |

| Presence of dental problems | 65.7 | 3.157 | 0.186-0.539 | <0.001 | 1.855 | 0.933-3.689 | 0.078 |

| Opinion of teeth, gums and prosthesis | |||||||

| Goodorexcellent | 34.8 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| Fair | 60.2 | 2.837 | 1.821-4.421 | <0.001 | 1.975 | 0.929-4.199 | 0.077 |

| Poor orverypoor | 70.1 | 4.401 | 2.704-7.163 | <0.001 | 5.785 | 2.391-13.99 | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||||

| South | 49.6 | 1 | 0.192 | 1 | 0.433 | ||

| Southeast | 38.7 | 1.561 | 0.970-2.513 | 0.066 | 0.631 | 0.248-1.608 | 0.335 |

| Midwest | 43.8 | 1.265 | 0.778-2.045 | 0.343 | 0.498 | 0.210-1.178 | 0.113 |

| Northeast | 51.9 | 0.911 | 0.539-1.539 | 0.727 | 0.988 | 0.385-2.539 | 0.981 |

| North | 49.1 | 1.020 | 0.539-1.930 | 0.951 | 0.939 | 0.294-2.998 | 0.916 |

| Philanthropic LSIE | 46.4 | 1.887 | 0.907-3.927 | 0.085 | 1.272 | 0.289-5.596 | 0.750 |

| Toothlessness | 42.2 | 0.746 | 0.538-1.035 | 0.079 | 0.974 | 0.171-5.555 | 0.977 |

| Functionaltoothlessness | 43.3 | 0.577 | 0.369-0.902 | 0.015 | 0.588 | 0.278-1.241 | 0.163 |

| Upperprosthesisabsent | 48.4 | 1.296 | 0.935-1.798 | 0.120 | 0.719 | 0.342-1.513 | 0.385 |

| Lowerprosthesisabsent | 48.7 | 1.677 | 1.146-2.453 | 0.007 | 3.722 | 0.822-16.85 | 0.088 |

| Needforlowerprosthesis | 47.4 | 1.342 | 0.922-1.953 | 0.124 | 0.730 | 0.184-2.903 | 0.655 |

| DMFT > 28.9 | 43.5 | 0.762 | 0.533-1.09 | 0.137 | 1.157 | 0.544-2.462 | 0.705 |

* NSR (%): Negative self-rating in percentage values; p< 0.05 were considered significant for the statistical tests; PR cr – crude prevalence ratio; PR adjust – adjusted prevalence ratio; CI – 95% confidence interval; Hosmer and Lemeshow test = 0.750; a – Chi-square test

Table 4: Multivariate analysis of the Pain and Discomfort Dimension of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index in institutionalized elderly in Brazil

In the psychosocial dimension, the following variables remained significant in the model after multivariate analysis: opinion about teeth, gums and/or prosthesis, absence of upper prosthesis and the need for upper prosthesis (Table 2).

For the physical dimension of GOHAI, where elderly participants express a general opinion about the status of their teeth, gums or prostheses, individuals that rated their condition as fair or poor also exhibited negative self-perception.

Finally, in relation to pain, only the variable of opinion about teeth, gums or prostheses remained significant. Therefore, elderly subjects who described their condition as bad or terrible were 5 times more likely to exhibit negative self-evaluation in the aforementioned dimension.

Discussion

Psychosocial dimension

This aspect involves psychological issues, emotional and socioeconomic, as well as cultural and spiritual issues [35]. Thus, this dimension shows how the individual behaves in society, its concern or care of their oral health, dissatisfaction with appearance, self-awareness on oral health and avoidance of social contacts due to dental problems [18]. It is worth pointing out that the body changes determined by the aging process have psychosocial implications that results and generates events that cause different behaviors such as inactivity, loneliness, isolation and prejudice [36].

After data analysis, it was identified that when institutionalized elderly participants exhibited an absence of or need for rehabilitation in the upper arch, their self-assessment in the psychosocial dimension of the GOHAI was negative. This is because the absence of upper teeth generates social, psychological and functional limitations, primarily in relation to esthetic questions [19]. These individuals experience eating difficulties and likely feel restricted in the presence of others. Another element concerns communication difficulties. Despite being institutionalized, subjects manifest their individuality regardless of living in a collective environment [37].

Furthermore, literature studies have shown that the absence of teeth may have a negative influence on self-rated oral health [38-40], and that the elderly tend to improve in this area after rehabilitation [41-44].

With regard to opinion about teeth, gums and/or prostheses, psychosocial dimension results were not surprising. This is because individuals displayed negative self-evaluation when expressing a bad opinion about their poor oral health conditions, confirming GOHAI results.

Physical dimension

Consists in physical function, physical performance, physical pain and general health also involving issues of eating, speaking and swallowing [18,45,46].

The aging process promotes changes in orofacial functions, these are related to adjustments in oral functions caused by tooth loss, use of poorly fitting dentures, loss of muscle tone and psychomotor retardation [47,48]. Still occur changes in taste perception, the elderly may lead to loss of desire to eat, chew and pleasure in the act of eating. Due to adversity elderly seeks less consistent food and at the same time it can cause atrophy of the masticatory muscles, with repercussions in facial aesthetics and self-esteem [48,49].

Regarding elderly who have natural teeth, those related problems concerns to periodontal aspects, which make the teeth less steady and chewing extremely difficult [48].

When analyzing the data, it was observed that subjects exhibiting dental problems, diagnosed with periodontal attachment loss of 6mm or more, demonstrated negative self-perception on physical dimension questions. PAL results indicate severe periodontal attachment loss and dental mobility. Thus, self-reported dental issues may translate into dental mobility since the aged do not associate it with periodontal problems. These findings are confirmed in the literature, where studies indicate periodontal problems may be predictors of self-assessed oral health [50,51].

Pain/Discomfort Dimension

Pain is one of the most common reasons for older people to seek medical attention [52] and this can be defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with present or potential tissue damage. The pain is always subjective. Each individual learns to use this term through their previous experiences related to damages.” In other words, pain is considered a multifactorial phenomenon, which sensation and perception will vary individually, according to the influence of biological, psychological and social factors [53].

Pain is also related to the discomfort while chewing, tooth and gum sensitivity and finally the need for medications to relieve pain or discomfort for the oral cavity [18,46].

Through the literature review it can be seen that the absence of teeth can have different meanings for those who lose. Among them we can mention the mutilations to the body, in other words, the view that the elderly have on how his tooth was lost, representing a real aging and when there are indications of prosthesis. These meanings can interfere negatively, because it promotes a feeling of shame and creates the expectation that the prosthesis can replace the original tooth, performing the same function with equivalent quality. Fear of long treatments, and the greater cost for conservative treatment, encourage the transition to the edentulism [48].

In the study of Unfer et al . [54], it was reported by the elders that the reason for loss of teeth is associated with the lack or difficulty of access to dental services, lack of knowledge about the causes and control of dental disease and the consequence of the dental care model, this, may be explained by the surgical-restorative attention model used in the past [54]. With data analysis, only the opinion of teeth, gums or dentures had significant value and thus the elderly who described their condition as poor or very poor, presented higher conditions of a negative self-perception.

Conclusion

Results show that GOHAI analysis, mediated by the psychosocial, physical and pain dimensions, showed correlations with variables expressing these dimensions, primarily with regard to objective oral health conditions. These findings underscore that both subjective and objective aspects have an impact on self-rated oral health. Clinicians are therefore recommended to carefully assess elderly patients’ complaints, considering their frailties and comorbidities.

The use of self-perception of oral health assessments as GOHAI dimensions, can reveal information that is not obtained by objective indicators of oral diseases, to mention the psychological and social factors that may contribute to public health planning that promotes health and compose preventive and rehabilitation actions as well as activities to guide and encourage the elderly to the importance of selfcare [55,56].

Finally, a better understanding of relationships established between self-rated oral health based on GOHAI dimensions may increase knowledge of oral health conditions among institutionalized elderly in Brazil, thereby contributing to action planning, organization and monitoring of health services [57] besides improved health and quality of life [58].

References

- Fonseca PHA, Almeida AM, Silva AM (2011) Oral health conditions of institutionalized elderly. RGO-Rev Gaúcha Odontol 59: 193-200.

- Karla Giovana Bavaresco Ulinski,Mariele Andrade do Nascimento,Arinilson Moreira Chaves Lima,Ana Raquel Benetti,Regina Célia Poli-Frederico Factors Related to Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Independent Brazilian Elderly. Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Journal of Dentistry Volume 2013, Article ID 705047.

- Castrejón-Pérez RC,Borges-Yáñez SA,Gutiérrez-Robledo LM,Avila-Funes JA (2012) Oral health conditions and frailty in Mexican community-dwelling elderly: a cross sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 12: 773.

- de Souza EH,Barbosa MB,de Oliveira PA,Espíndola J,Gonçalves KJ (2010) Impact of oral health in the daily life of institutionalized and non-institutionalized elder in the city of Recife (PE, Brazil). Cien Saude Colet 15: 2955-2964.

- McGrath C, Bedi R (2004) Why are “weigthting” an assessment of a self-weigthing approach to measuring oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 32: 19-24.

- Wu B,Plassman BL,Liang J,Remle RC,Bai L, et al. (2011) Differences in Self-Reported Oral Health Among Community-Dwelling Black, Hispanic, and White Elders. Journal of Aging and Health 23 267–288.

- Joaquim AM, Wyatt CC, Aleksejuniene J, Greghi SL, Pegoraro LF, et al. (2010) A comparison of the dental health of Brazilian and Canadian independently living elderly. Gerodontology. 27: 258-265.

- Daly B, Newton T, Batchelor P, Jones K (2010) Oral health care needs and oral health-related quality of life (OHIP-14) in homeless people. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 38: 136-144.

- Locker D, Allen F (2007) What do measures of “oral health-related quality of life” measure? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 35: 401-411.

- Brondani MA, McEntee MI (2007) The concept of validity in social dental indicators and oral health-related quality of life measures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 35: 472-478.

- Lawrence HP, Thonson WM, Broadbent JM, Poulton R (2008) Oral health-related quality of life in a birth cohort of 32-years olds. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 36: 305-316.

- Zhu HW, McGrath C, McMillan AS, Li LSW (2008) Can caregivers be used in assessment oral health-related quality of life among patients hospitalized for acute medical conditions? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 36: 27-33.

- Liu H, Maida CA, Spolsky VW, Shen J, Li H, et al. (2010) Calibration of self-reported oral health to clinically determined standards. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 38: 527-539.

- Luciana Correia Aragão de Vasconcelos, Raimundo Rosendo Prado Júnior, João Batista Mendes Teles, Regina Ferraz Mendes (2012) Self-perceived oral health among elderly individuals in a medium-sized city in Northeast Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 28: 1101-1110.

- Meng X, Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Heft MW (2007) Satisfaction With Dental Appearance Among Diverse Groups of Dentate Adults. J Aging Health 19: 778-791.

- Martins AM, Barreto SM, Pordeus IA (2009) Objetive and subjetive factors related to self-rated oral health among the elderly. Cad Saude Publica 25: 421-34.

- Piuvezam G, Lima KC (2011) Self-perceived oral health status in institutionalized elderly in Brazil. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 55: 5–11.

- Benyaminy Y, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Self rated oral health as an independent predictor of self rated general health, self esteem and life satisfaction. Soc Sci Med 2004; 59:1109-1116.

- Piuvezam G, Ferreira AAA, Alves MSCF (2006) The dental losses on the third age: a study of social representation. Cad. Saúde colet 14: 597-614.

- Fuentes-García A, Lera L, Sánchez H, Albala C (2012) Oral health-related quality of life of older people from three South American cities. Gerodontology 30: 67-75

- Kshetrimayum N, Reddy CVK, Siddhana S, Manjunath M, Rudraswamy S et al.(2012) Oral health-related quality of life and nutritional status of institutionalized elderly population aged 60 years and above in Mysore City, India. Gerodontology 30: 119–125.

- Deshmukh SP, Radke UM. Translation and validation of the Hindi version of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. Gerodontology 29: 243.

- Franchignoni M, Giordano A, Levrini L, Ferriero G, Franchignoni F(2010) Rasch analysis of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. Eur J Oral Sci 118: 278–283.

- Sánchez-García S, Heredia-Ponce E, Juárez-Cedillo T, Gallegos-Carrillo K, Espinel-Bermúdez C, et al. (2010) Psychometric properties of the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) and dental status of an elderly Mexican population. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 70: 300–307.

- Atchinson KA (1997) The General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI). In Slade GD ed.. Measuring oral health and quality of life. Departament of Dental Ecology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC

- Marco Cornejo,Glòria Pérez,Kenio-Costa de Lima,Elías Casals-Peidro,Carme Borrell (2013) Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in institutionalized elderly in Barcelona (Spain). Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 18: e285-92.

- Andrade FB, Lebrão ML, Santos JLF, Cruz Teixeira DS, Oliveira Duarte YA (2012) Relationship Between Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, Oral Health, Socioeconomic, and General Health Factors in Elderly Brazilians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 60: 1755-1760.

- Gil-Montoya JA, Subirá C, Ramón JM, Gonzáles-Moles MA (2008) Oral health-related quality of life and nutrition status. J Public Health Dent 68: 88-93.

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, et al. (2007) Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335: 806-808.

- Brazil. Law 8842, enacted in January 4, 1994, which "provides for a National Policy for the Elderly, creates the National Council for the Elderly and other measures". Brasilia: Official Gazette of the Federative Republic of Brazil 1996; 128: 12277-12279

- Silva SRC. Self-perception of oral health conditions with people with 60 or more years. [tese] São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo: 1999. p.88. [Article in Portuguese]

- Dolan TA, Peek CW, Stuck AE, Beck JC (1998) Function health and dental service use among older adults. J Gerontol Med Sci 53: 413-418.

- Oral Health surveys: basic Methods (1998) World Health Organization Geneva, Switzerland.

- Gift HC, Atchinson KA, Durry TF (1998) Perceptions of the natural dentition in the context of multiple variables. J Dent Res 77: 1529-1538.

- Tourinho GF, Nunes MO (2007) Psychosocial dimension: perceptions of medical of an institution-school of city Salvador. Page: 200. [Article in Portuguese]

- Santana MS (2011) Psychosocial dimension of physical activity in the oldness. Fractal: Revista de Psicologia 23: 337-352

- Piuvezam G (2004) Estudo psicossocial das perdas dentárias na terceira idade. Natal: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

- Walker RJ, Kiyak HA (2007) The impact of providing dental services to frail older adults: perceptions of elders in adult day health centers. Spec Care Dentist 27: 139-143.

- Swoboda J, Kiyak HA, Persson RE, Persson GR, Yamaguchi DK, et al. (2006) Predictors of oral health quality of life in older adults. Spec Care Dentist 26: 137-144.

- Steele JG, Sanders AE, Slade GD, Allen PF, Lahti S, et al. (2004) How do age and tooth loss affect oral health impacts and quality of life? A study comparing two national samples. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 32: 107-114.

- Shigli K, Hebbal M (2010) Assessment of changes in oral health-related quality of life among patients with complete denture before and 1 month post-insertion using Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. Gerodontology 27: 167-173.

- Nicolas E, Veyrune JL, Lassauzay C (2010) A six-month assessment of oral health-related quality of life of complete denture wearers using denture adhesive: a pilot study. J Prosthodont 19: 443-448.

- Veyrune JL, Tubert-Jeannin S, Dutheil C, Riordan PJ (2005) Impact of new prostheses on the oral health related quality of life of edentulous patients. Gerodontology 22: 3-9.

- Santos FB, Morais MB, Barbosa AS, Sampaio FC, Forte FDS (2007) Self perception in oral health in old people from the Family Health Program, Health Distric III- João Pessoa- PB. Arq Cent Estud Curso Odontol Univ Fed Minas Gerais 43: 23-32. [Article in Portuguese]

- Severo M, Santos AC,Lopes C,Barros H, (2006) Reliability and validity in measuring physical and mental health construct of the portuguese version of MOS SF-36. Acta Med Port 19: 281-288.

- Gonçalves PMC (2008) Avaliação da qualidade de vida, relacionada com a saúde oral, dos infivíduos portadores de próteses dentárias removíveis totais e parciais. Universidade Fernando Pessoa Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde – Porto.

- Cardoso MCAF (2010) Sistema estomatognático e envelhecimento: associando as características clínicas miofuncionais orofaciais aos hábitos alimentares. Tese (Doutorado) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Instituto de Geriatria e Gerontologia. Porto Alegre.

- Cardoso MCAF, Bujes RV (2010) Saúde bucal e as funções da mastigação e deglutição nos idosos. Estud. interdiscipl. envelhec., Porto Alegre 15: 53-67.

- Silva LG, Goldenberg M (2009) A mastigação no processo de envelhecimento. Rev CEFAC 3: 27-35.

- Guzeldemir E, Toygar HU, Tasdelen B, Torun D (2009) Oral health-related quality of life and periodontal health status in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Dent Assoc 140: 1283-1293.

- Silva SRC, Castellanos Fernandes R (2001) Auto-percepçäo das condições de saúde bucal por idosos. Rev Saude Publica. 35: 349-355.

- Pereira LS,Sherrington C,Ferreira ML,Tiedemann A,Ferreira PH et al. (2014) Self-reported chronic pain is associated with physical performance in older people leaving aged care rehabilitation. Clin Interv Aging 9: 259-265.

- Portnoi AG (1999) Dor, Stress e Coping: grupos operativos em doentes com síndrome de fibromialgia. de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo

- Unfer B, Braun K, da Silva CP, Filho LDP (2006) Autopercepção da perda de dentes em idosos. Interface Comunic Saúde Educ 10: 217-26

- Fonseca PHA, et al. (2011) Condições de saúde bucal em população idosa institucionalizada. RGO - Rev Gaúcha Odontol 59: 193-200.

- Alcarde ACB et al. (2010) A cross-sectional study of oral health-related quality of life of Piracicaba’s elderly population. Rev. odonto ciênc 25: 126-131.

- Moura C, Cavalcante FT , Catao MHCV , Gusmao ES , Sosres RSC et al. (2011) Fatores Relacionados ao Impacto das Condições de Saúde Bucal na Vida Diária de Idosos, Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brasil. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr 11: 553-559.

- Silva DD, Held RB, Souza Torres SV, Sousa MLR, Neri AL et al. (2011) Autopercepção da saúde bucal em idosos e fatores associados em Campinas, SP, 2008-2009. Rev Saúde Pública 45: 1145-1153.

Relevant Topics

- Advanced Bleeding Gums

- Advanced Receeding Gums

- Bleeding Gums

- Children’s Oral Health

- Coronal Fracture

- Dental Anestheia and Sedation

- Dental Plaque

- Dental Radiology

- Dentistry and Diabetes

- Fluoride Treatments

- Gum Cancer

- Gum Infection

- Occlusal Splint

- Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

- Oral Hygiene

- Oral Hygiene Blogs

- Oral Hygiene Case Reports

- Oral Hygiene Practice

- Oral Leukoplakia

- Oral Microbiome

- Oral Rehydration

- Oral Surgery Special Issue

- Orthodontistry

- Periodontal Disease Management

- Periodontistry

- Root Canal Treatment

- Tele-Dentistry

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16465

- [From(publication date):

March-2015 - Apr 26, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11706

- PDF downloads : 4759