Research Article Open Access

Oral Health of Children and Adolescents in Da Nang

Brittmarie Jacobsson1*, Ho Thi Thanh2, Hoang Ngoc Chuong2 and Anders Hugoson1

1Centre for Oral Health, School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

2Dental Department, Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy, Da Nang, Vietnam

- *Corresponding Author:

- Brittmarie Jacobsson

Centre for Oral Health

School of Health Sciences

Jönköping University

SE-551 11 Jönköping, Sweden

Tel: 46036101342

E-mail: brittmarie.jacobsson@hj.se

Received Date: June 16, 2014; Accepted Date: July 14, 2014; Published Date: July 21, 2014

Citation: Jacobsson B, Thanh HT, Chuong HN, Hugoson A (2014) Oral Health of Children and Adolescents in Da Nang. J Oral Hyg Health 2:145. doi: 10.4172/2332-0702.1000145

Copyright: © 2014 Jacobsson B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Oral Hygiene & Health

Abstract

This is a cross-sectional epidemiological study comprising 840 randomly selected children in the age groups of 3, 5, 10 and 15 year olds. All children were clinically examined for number of teeth, dental caries, dental fillings, plaque, gingivitis and probing pocket depth. Dental care and dietary habits were collected using a self-reported questionnaire. Among 3 and 5 year olds, 98% suffered from dental caries, compared to 91% of 10 and 15 year olds. The mean (SD) of decayed (initial and manifest) and filled tooth surfaces (dfs/DFS) in the different age groups was: 18.2 (14.1), 23.0 (15.4), 5.1 (4.2) and 6.9 (6.0), respectively. There was an average of ~ 30% in all age groups with plaque and gingivitis. Consuming milk with sugar more than 2–3 times a week (3 and 5 year olds) and eating sweets between principal meals twice a day (in 10 and 15 year olds) were statistically significant with caries prevalence. It is concluded that dental caries and gingivitis are significant public health problems among children in Da Nang, Vietnam.

Keywords

Child dentistry; Epidemiology; Public health dentistry

Introduction

In 1989, “The First National Oral Health Survey” of the population in Vietnam [1] was performed and it reported poor oral hygiene status and a moderate level of caries among a sample of 2.762 individuals aged 12-15 years. In 1999, “The National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam” (NOHSV1999) [2,3] was conducted to characterize the oral health of the Vietnamese Child population and this report enabled the exploration of trends in oral health in Vietnam [4]. Dental carieswas found to be highly prevalent and severe, but there was also considerable variation in caries prevalence between different geographic areas. There was an increase in caries prevalence in 1999 compared with the study performed ten years earlier. Further studies in Dang Phuong village in the Central Highlands and four small rural villages in Southern Vietnam [5] showed that dental caries was prevalent in both primary and permanent dentitions of these populations, with high caries prevalence in the primary dentition associated with a high consumption of dietary sugars, notably sticky candies and soft drinks. These findings highlighted an urgent need for professional dental care and preventive measures and a change from restoration oriented dental treatment to dental public health services. Several studies in Asian countries among preschool and school children from China [6] Thailand [7] Laos [8] and Myanmar [9] have shown variations between high and low prevalence of dental caries. In the light of changing living conditions, it is expected that the incidence of dental caries will increase in many low and middle-income populations, especially as a result of the increasing consumption of sugars, inadequate exposure to fluorides and exposure of these countries to Western diets. Before new population-wide strategies or programs for oral health care promotion and prevention can be implemented, a more contemporary and thorough analysis of the oral health status of the population (especially preschool and schoolchildren) must be conducted [10]. To deepen the co-operation in Oral Health Science between the universities in Jönköping, Sweden, and Da Nang, Vietnam, and to provide information necessary for planning and implementation of an effective oral health program, a cross-sectional epidemiologicalstudy was performed. The aim was to describe the sociodemographic conditions and the oral health status of 3, 5, 10 and 15 year-olds in Da Nang, Vietnam. The present paper presents clinical data relating to dental caries, oral hygiene and the periodontal condition in these four age groups, complemented with statistical analysis of the association between dental caries and some of its potential determinants.

Materials and Methods

Ethical issues

Throughout the study, the ethical roles for research described in the Helsinki Declaration [11] and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [12] were followed. The study was approved by the Ministry of Health in Vietnam (No: 3909/BYT-DK2T), the director of the staff at Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy and the Local Health Authority and Training and Education Bureau in Da Nang (No: 2127/GD&DT-VP). It was also approved by the respective school head-teachers. Parental permission (written consent) was gained for every child and the participation of these children in the study was voluntary. Subjects were explicitly informed that they had the right to withdraw at any point without giving any reason. All children were promised individualized treatment based on their acute needs.

Study population

Da Nang is one of the largest cities in central Vietnam, located between Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City with a population of approximately one million inhabitants. All subjects were inhabitants of the city of Da Nang and were selected from one rural and six urban districts and from three randomly selected schools in each district (one kindergarten, one primary school and one senior high school). The study population was comprised of 840 randomly selected children, 210 in each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. Children were randomly selected by their year and month of birth (January to July). The final sample consisted of 745 individuals: 160, 182, 200 and 203 in each age group, respectively. The urban districts were: Thanh Khe, Hai Chau, Son Tra, Ngu Hanh Son, Lien Chieu and Cam Le; the rural district was Hoa Vang. The sampling was performed in co-operation with the dental department at Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy. Each child in the age groups received a personal invitation (for the 3 and 5 year-olds it was sent to the parents) informing them of the purpose of the questionnaire and that a clinical examination of the teeth would be performed.

Clinical examination

All children were clinically examined by four examiners: one Swedish dental hygienist from Jönköping University and three Vietnamese dentists from Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy. All Vietnamese examiners had previously been residents in Jönköping as exchange teachers at Jönköping University. All examiners were trained both in Jönköping and in Da Nang according to the clinical examination criteria of the study. Four dental hygienist assistants were responsible for recording the results. A dental hygienist co-ordinated the examination schedule and acted as a contact between the research team and school teachers. The clinical examination was performed by examiners using a portable dental chair, light from a head lamp, two mirrors, one WHO probe, one explorer one tweezers and cotton wool. All instruments were cleaned and sterilized in a portable autoclave. All clinical examinations in a given district were completed in a single day.

Number of teeth

Primary teeth were recorded in the 3 and 5 year olds. In the 10 and 15 year olds, only permanent teeth, excluding third molars, were recorded.

Dental caries

Each tooth surface was examined clinically for dental caries according to the literature [13,14] and the criteria set up by Koch [15], namely that ‘initial caries’ was typified by “a loss of mineral in the enamel giving a chalky appearance but without any clinical cavitation” and ‘manifest caries’ presents as “new caries lesions on surfaces not previously restored and of such an extent that they could be verified as cavities by probing and/or that probing in fissures using light pressure results in the probe becoming stuck”.

Decayed and filled primary and permanent tooth surfaces

The individual number of decayed (initial + manifest) and filled primary (dfs) and permanent (DFS) tooth surfaces was calculated.

Fissure sealants

The presence of any fissure sealed occlusal surface was recorded.

Plaque

The presence of visible plaque was recorded for all tooth surfaces after drying with air according to the criteria for plaque indices (PLI) grades two and three [16].

Gingivitis

The occurrence of gingival inflammation corresponding to gingival indices (GI) grades two and three was recorded for all tooth surfaces. Gingival inflammation was thus registered if the gingiva bled on gentle probing [17].

Probing pocket depth

The probing pocket depth was recorded in all 15 year olds. Probing pocket depth (in mm) was recorded on the first permanent molars and on permanent incisors using a WHO periodontal probe.

Questionnaire

As a part of a larger questionnaire, the parents of the 3 and 5 year olds received questions on oral health care and dietary habits to answer at home some days prior to the clinical examination. In connection to the clinical examination, a modified questionnaire was given to the 10 and 15 year olds to be answered by themselves after being given instructions by an examiner. The questions in both questionnaires have been validated and used previously in earlier epidemiological studies in Sweden [18], but were modified here to reflect local Vietnamese conditions. The questionnaire was translated from Swedish into English into Vietnamese and then translated back into English in order to verify the translation accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented. The degree of association between dental caries (dfs/DFS) and a range of potential determinants from the questionnaire and the clinical examination was investigated using linear regression, with dfs/DFS as the dependent variable with 3 and 5 year olds in one group and 10and 15 year olds in another group. Bivariate models were run between dental caries and all potential determinants. Statistically significant associations between caries and specific variables highlighted by the bivariate analyses were further analysed using multivariate linear regression models. Age and gender were always included in these multivariate models, together with other variables that remained statistically significant. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS for Windows Statistical Software Package (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Non-respondents

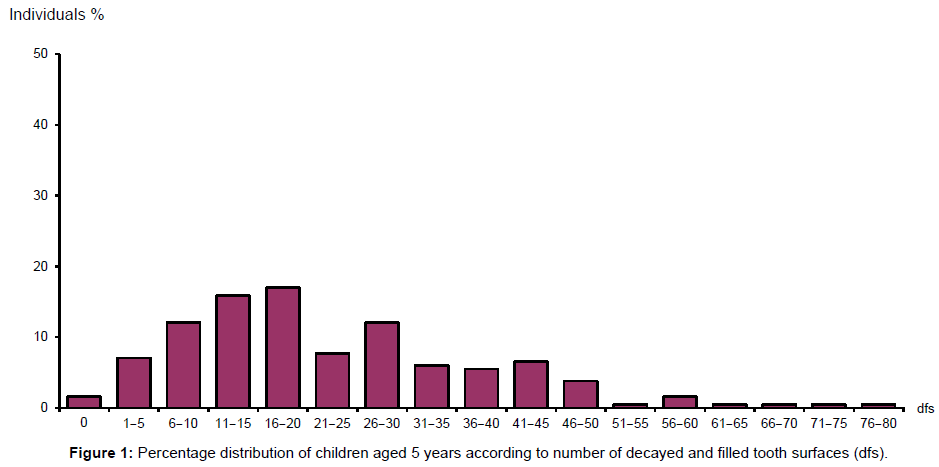

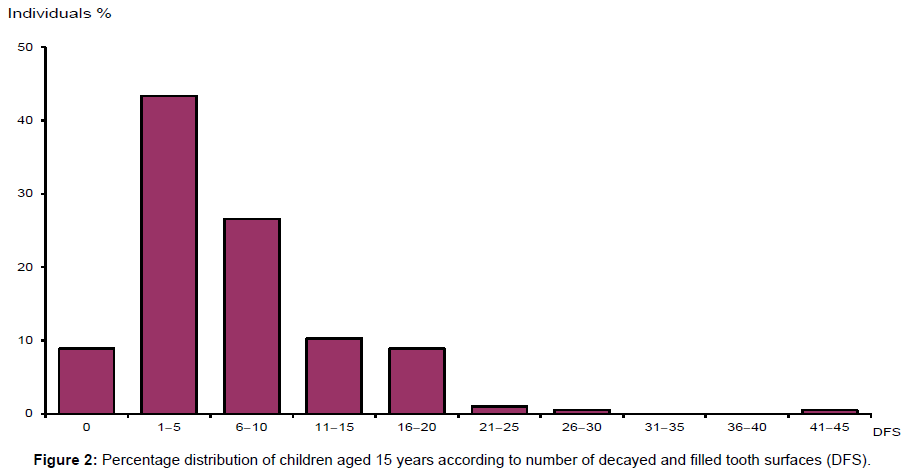

Sixty individuals across the four age-groups were absent from school and, therefore, were not included in the investigation. Twentytwo individuals did not agree to participate and thirteen individuals had missing data and were excluded from the final sample of 745 individuals. The mean (SD) of the number of teeth sub-divided by age group and gender is shown in Table 1 for 3 and 5 year olds and in Table 2 for 10 and 15 year olds. The mean (SD) values for decayed and filled teeth (dft/DFT), decayed (ds/DS) and filled (fs/FS) tooth surfaces, and decayed and filled (dfs/DFS) tooth surfaces are also given for the different age groups. Caries data is separated into “initial” and “manifest” caries. The percentage of children with caries among 3 and 5 year olds was 98%; and 91% for both 10 and 15 year olds. The distribution of decayed and filled primary tooth surfaces (dfs) in children aged 5, and that of decayed and filled permanent tooth surfaces (DFS) in children aged 15 years, is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. The most frequent values of dfs and DFS were 16–20 and 1–5, respectively. The maximum dfs was 76–80, and there was a significant number of children with dfs between 20 and 50. In contrast, the vast majority of DFS was less than 20. There was lower caries prevalence in the permanent dentition than in primary teeth. Molars with fissure-sealed occlusal surfaces were found in 18 (9%) 10year-olds and in 3 (1%) 15 year olds. These were mostly on the mandibular first molars (30 surfaces) but were also commonly found on the maxillary first molars (9 surfaces) and mandibular second molars (5 surfaces). The mean numbers of tooth surfaces displaying plaque and gingivitis (calculated as the percentage of the total number of existing tooth surfaces) divided by age groups, are given in Table 3 and 4. Plaque scores were similar across the four age groups, but gingivitis scores tended to be higher in the older children compared to the 3 and 5 year olds. Pocket probing depths of 4–5 mm were found in 10 (5%) 15 year olds around the right maxillary first molar (proximal, 9 pockets), right maxillary central incisor (proximal, 5 pockets), left maxillary first molar (proximal and buccal, 10 pockets) and the right mandibular first molar (proximal, 2 pockets). When the statistically significant explanatory variables from the bivariate analysis of the questionnaire and clinical data were further analysed using multivariate linear regression models for dfs/DFS, adjusted for age and gender, consuming milk with sugar more than 2-3 times a week (3 and 5 year olds), eating sweets between principal meals twice a day, and having knowledge about the use of dental floss for cleaning between teeth and the amount of plaque (in 10 and 15 year olds) remained statistically significant to caries prevalence (Tables 4-6). The consumption of fruit juice between meals 2-3 times a week (in 3 and 5 year olds) and the consumption of snacks 2-3 times a day (in 10 and 15 year olds) were no longer statistically significant in the final linear regression models. Oral health care habits, fluoride use, knowledge on dental diseases and the consumption of soft drinks, fruit, cakes/candy, sweet soup and yoghurt between principal meals had no statistically significant association with dental caries prevalence.

| 3-years | 5-years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=160 Mean (SD) | Boys n=87 Mean (SD) | Girls n=73 Mean (SD) | Total n=182 Mean (SD) | Boys n=93 Mean (SD) | Girls n=89 Mean (SD) | ||

| Number of teeth | 19.9 (0.7) | 19.9 (0.3) | 19.8(1.0) | 19.8 (0.7) | 19.8 (0.8) | 19.8 (0.6) | |

| Initial caries | 9.6 (8.7) | 9.3 (8.8) | 10.0 (8.6) | 7.2 (6.1) | 7.3 (6.1) | 7.2 (6.1) | |

| Manifest caries | 8.3 (10.1) | 8.8 (10.5) | 7.8 (9.6) | 14.8 (14.7) | 16.2 (14.8) | 13.4 (14.6) | |

| Fillings | 0.3 (1.2) | 0.3 (1.4) | 0.2 (0.8) | 1.0 (3.2) | 0.7 (2.7) | 1.3 (3.6) | |

| Total dfs(Initial and manifest) | 18.2 (14.1) | 18.4 (14.9) | 18.0 (13.1) | 23.0 (15.4) | 24.2 (15.6) | 21.8 (15.2) | |

| Total dfs (manifest) | 8.6 (10.2) | 9.1 (10.7) | 8.0 (9.6) | 15.8 (14.7) | 16.9 (14.8) | 14.6 (14.7) | |

| Total dft(Initial and manifest) | 10.6 (5.7) | 10.5 (6.3) | 10.9 (5.1) | 11.6 (4.8) | 12.0 (4.8) | 11.1 (4.9) | |

| Total dft(manifest) | 5.2 (4.5) | 5.5 (4.9) | 4.9 (4.0) | 7.8 (4.9) | 8.3 (4.6) | 7.3 (5.1) | |

Table 1: Total number of teeth with initial and manifest carious lesions and fillings in 3- and 5-year-olds, divided by gender. Mean values, with standard deviation (SD). Decayed and filled tooth surfaces (dfs) and teeth (dft).

| 10-years | 15-years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=200 Mean (SD) | Boys n=100 Mean (SD) | Girls n=100 Mean (SD) | Total n=203 Mean (SD) | Boys n=89 Mean (SD) | Girls n=114 Mean (SD) | ||||

| Number of teeth | 19.1 (4.9) | 18.0 (5.0) | 20.3 (4.5) | 27.8 (0.5) | 27.8 (0.5) | 27.8 (0.5) | |||

| Initial caries | 2.4 (3.2) | 2.7 (3.2) | 2.1 (3.2) | 2.0 (3.7) | 2.9 (4.4) | 1.3 (2.9) | |||

| Manifest caries | 2.5 (2.4) | 2.5 (2.6) | 2.5 (2.2) | 4.6(4.5) | 4.4 (5.0) | 4.7 (4.0) | |||

| Fillings | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.3 (1.1) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.4 (1.3) | |||

| Total DFS(Initial and manifest) | 5.1 (4.2) | 5.3 (4.3) | 4.9 (4.1) | 6.9 (6.0) | 7.5 (7.2) | 6.4 (4.8) | |||

| Total DFS (manifest) | 2.7 (2.5) | 2.6 (2.7) | 2.8 (2.3) | 4.9 (4.7) | 4.6 (5.1) | 5.1 (4.3) | |||

| Total DFT(Initial and manifest) | 4.0 (3.3) | 4.1 (3.2) | 3.9 (3.4) | 5.4 (4.2) | 5.9 (4.9) | 4.9 (3.4) | |||

| Total DFT(manifest) | 1.9 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.6) | 3.5 (2.9) | 3.4 (3.1) | 3.7 (2.7) | |||

Table 2: Total number of teeth with initial and manifest carious lesions and fillings in 10- and 15-year-olds, divided by gender. Mean values, with standard deviation (SD). Decayed and filled tooth surfaces (DFS) and teeth (DFT).

| 3-years | 5-years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=160 Mean (SD) | Boys n=87 Mean (SD) | Girls n=73 Mean (SD) | Total n=182 Mean (SD) | Boys n=93 Mean (SD) | Girls n=89 Mean (SD) | ||

| Plaque PLI (%) | 36.5 (0.2) | 36.2 (0.3) | 36.8 (0.2) | 31.8 (0.2) | 31.0 (0.3) | 32.6 (0.2) | |

| Gingivitis GI (%) | 32.5 (0.2) | 32.9 (0.2) | 32.2 (0.2) | 30.0 (0.2) | 30.1 (0.2) | 29.9 (0.2) | |

Table 3:Mean number of tooth surfaces with plaque and gingivitis in 3- and 5-year-olds, divided by gender, calculated as the percentage of existing tooth surfaces.

| 10-years | 15-years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=200 Mean (SD) | Boys n=100 Mean (SD) | Girls=100 Mean (SD) | Total n=203 Mean (SD) | Boys=89 Mean (SD) | Girls=114 Mean (SD) | |

| Plaque PLI (%) | 33.6 (0.3) | 35.6 (0.3) | 31.7 (0.3) | 31.0 (0.3) | 32.0 (0.3) | 30.2 (0.3) |

| Gingivitis GI (%) | 36.6 (0.2) | 38.2 (0.2) | 35.1 (0.2) | 45.8 (0.2) | 49.5 (0.2) | 43.0 (0.2) |

Table 4: Mean number of tooth surfaces with plaque and gingivitis in 10- and 15-year-olds, divided by gender, calculated as the percentage of existing tooth surfaces.

| Unstandardized B | SE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 18.52 | 2.01 | 0.001 |

| Age | |||

| 3-year-old | Ref. | ||

| 5-year-old | 4.47 | 1.70 | 0.009 |

| Gender | |||

| Girl | Ref. | ||

| Boy | 1.57 | 1.60 | 0.326 |

| Milk with sugar > 3 times a day |

2.68 | 3.07 | 0.383 |

| 2-3 times a day | -1.74 | 1.89 | 0.359 |

| Once a day | Ref. | ||

| 2-3 times a week | -13.04 | 5.13 | 0.012 |

| Once a week | 0.10 | 4.20 | 0.982 |

| Never | -1.24 | 2.94 | 0.672 |

Table 5: Association between tooth surfaces with initial and manifest carious lesions and fillings (dfs) and significant explanatory variables in 3- and 5-yearolds, analyzed by multivariate linear regression. SE denotes ‘standard error’; ‘Ref.’ shows the variable against which the other variables were compared statistically.

| Unstandardized B | SE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.60 | 1.01 | 0.011 |

| Age | |||

| 10-year-old | Ref. | ||

| 15-year-old | 1.89 | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Girl | Ref. | ||

| Boy | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.235 |

| Sweets between principal meals > Twice a day |

1.92 | 1.12 | 0.089 |

| Twice a day | 2.70 | 1.11 | 0.015 |

| Once a day | Ref. | ||

| Never | -0.14 | 0.62 | 0.825 |

| Dental floss is used for | . | ||

| Clean between teeth | Ref. | ||

| Whiten the teeth | 0.98 | 1.12 | 0.381 |

| Strengthen the enamel | 3.85 | 1.26 | 0.002 |

| I do not know | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.332 |

| Plaque | |||

| PLI ≤ 20% | Ref. | ||

| PLI 21% - 55% | 1.43 | 0.62 | 0.022 |

| PLI ≥ 56% | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.324 |

Table 6: Association between tooth surfaces with initial and manifest carious lesions and fillings (DFS) and significant explanatory variables in 10- and 15-yearolds, analyzed by multivariate linear regression. SE denotes ‘standard error’; ‘Ref.’ shows the variable against which the other variables were compared statistically.

Discussion

The results of this randomized epidemiological study in Da Nang, Vietnam, showed that almost all 3 and 5 year olds and 90% of 10 and 15 year olds suffered from initial and/or manifest dental caries. The prevalence of plaque and gingivitis was also very high, considerable more so than in a previous study of Vietnamese children [19]. There was a wide distribution of dfs among the 3 and 5 year olds with much higher modal and maximum scores than in the older children. The prevalence of dental caries was comparable with results obtained for schoolchildren during a national survey in 1999 [4] and with data from a study in southern rural Vietnam in connection with the Rotary Australian-Vietnam Dental Health Project where 93% of preschool children had an experience of caries [19]. This high caries prevalence means that many children will suffer pain (toothache) and functional difficulties (eating, sleeping) as a consequence. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that caries lesions in the primary dentition during the preschool years predispose for a high future risk of developing caries in the permanent dentition [20,21]. The dramatically lower modal and maximal DFS in the 10 and 15 year olds may reflect the fact that these older children have received several years of attention in a preventive program in Da Nang, whereas the 3 and 5 year olds have mainly had only dental treatment. All official data on dental caries, both nationally from Vietnam (National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam; NOHSV) and internationally (World Health Organization; WHO), report dental caries solely as manifest caries; initial caries is not reported. Omitting initial carious lesions may lead to an underestimation of the total caries situation, which in turn will affect the design, interpretation and apparent success of preventive measures. In this study, both initial and manifest carious lesions were used as criteria for dental caries, so the definition of caries must be taken into consideration when comparing with results from other studies [22,23]. It is also important to note that dental caries was only detected by clinical measures, so the results will likely differ from more comprehensive studies with radiographic images that will reveal more proximal caries. Due to the lack of radiographic information, this study has probably underestimated the dfs/DFS, but the method of including both initial and manifest caries more than doubled the number of carious lesions compared to the scores obtained when measuring only manifest caries. With regard to restorations, very few caries lesions had been restored (i.e. the filled [f/F] component was small in all age groups), which highlights the disparity between the treatment needs of these children and the professional dental resources available to provide this treatment. Furthermore, there were few fissure sealed molars found in the studied population. Expanded use of fissure sealants would probably result in a future marked decline in the frequency of decayed occlusal surfaces. Indeed, a Swedish epidemiological study [22] showed that most of the improvement seen in DFS among 10 and 15 year olds could be explained by the systematic use of fissure sealants on the occlusal surfaces of first permanent molars. The study also showed that the children had a high intake of sweets and inadequate frequency of toothbrushing with fluoride toothpaste. The importance of sweets for the prevalence of dental caries was further verified in the linear regression analysis in the current study where intake of milk with sugar 2-3 times a week and sweets between principal meals twice a day were the explanatory variables with the strongest association with the dependent variable. The parents seem to be unaware of the consequences of such habits. Almost all preschool children in this study were attending kindergarten for the whole day, meaning that kindergarten staff must assume an elevated level of responsibility for the preventive measures necessary to keep children’s teeth healthy. The importance of constant vigilance and the establishment of good oral hygiene habits is demonstrated by the evidence that these habits, including the use of fluoride toothpaste when established early in childhood, provide a foundation for reduced caries prevalence at the age of fifteen [24]. The result of this study should be used for both the planning of dental care resources in the long term and the evaluating of existing oral health preventive programs. The School Oral Health Promotion Program, with at-school delivery of oral health education relating to toothbrushing and mouth rinsing with fluoride solutions, has been implemented for more than 15 years in kindergartens and primary schools in Da Nang City. Inspite of this program, the study showed an extremely high prevalence of caries, gingivitis and poor oral hygiene among children and, also, that teeth with fissure sealant were rare. It has been suggested that a general discussion of the most effective caries preventive strategies might, for all age groups, be based on analysis of oral health determinants as a whole and, for the group with the highest dfs/DFS value, analysis should be population-based [22]. Of particular concern is the caries prevalence in the primary dentition. It is important to start the oral health preventive strategy with preventive measures as early as possible to meet the needs of children at high risk for caries.

Conclusion

The results of the study highlights the urgent need to implement a more effective School Oral Health Promotion Program in Da Nang City, which should be made available for all children in order to improve their oral health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eleonor Fransson, Associate Professor of epidemiology, School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, for statistical support. Futurum, the County Council of Jönköping and School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Sweden, for financial support. In Da Nang, Vietnam, financial assistance was supported by Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy; the Local Health Authority; and the Training and Education Bureau. Oral hygiene products were donated by TePe Oral hygiene Products (Malmö, Sweden) and Colgate-Palmolive (Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam).

References

- Ngo D, Vu T, et al. (1995) Vietnam Oral Health Status (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, Institute of Odontostomatology.

- Roberts-Thomson KF, Spencer AJ, Do LG, Szuster FS, Hai TD, et al. (2010) The Second National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam, 1999: background and methodology. N Z Dent J 106: 61-66.

- Roberts-Thomson KF, Spencer AJ (2010) The Second National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam--1999: variation in the prevalence of dental diseases. N Z Dent J 106: 103-108.

- LocGiang D, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF, HaiDinh T, ThuyThanh N (2011) Oral health status of Vietnamese children: findings from the National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam 1999. Asia Pac J Public Health 23: 217-27.

- Uetani M, Jimba M, Kaku T, Ota K, Wakai S (2006) Oral health status of vulnerable groups in a village of the Central Highlands, southern Vietnam. Int J Dent Hyg 4: 72-76.

- Zhang S, Liu J, Lo EC, Chu CH (2013) Dental caries status of Dai preschool children in Yunnan Province, China. BMC Oral Health 13: 68.

- Lueangpiansamut J, Chatrchaiwiwatana S, Muktabhant B, Inthalohit W (2012) Relationship between dental caries status, nutritional status, snack foods, and sugar-sweetened beverages consumption among primary schoolchildren grade 4-6 in NongbuaKhamsaen school, Na Klang district, NongbuaLampoo Province, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 95: 1090-1097.

- Jürgensen N, Petersen PE (2009) Oral health and the impact of socio-behavioural factors in a cross sectional survey of 12-year old school children in Laos. BMC Oral Health 9: 29.

- Phyo AZ, Chansatitporn N, Narksawat K (2013) Oral health status and oral hygiene habits among children aged 12-13 years in Yangon, Myanmar. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 44: 1108-1114.

- Pine CM, Harris R (2007) Community Oral Health. London, Quintessence.

- Williams JR (2008) The Declaration of Helsinki and public health. Bull World Health Organ 86: 650-652.

- United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York, United Nations.

- Fejerskov O, Kidd EAM (2008) Dental caries: the disease and its clinical management. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Munksgaard.

- Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB (2007) Dental caries. Lancet 369: 51-59.

- Koch G (1967) Effect of sodium fluoride in dentifrice and mouthwash on incidence of dental caries in schoolchildren. Odontol Revy 18,Suppl 12.

- SILNESS J, LOE H (1964) PERIODONTAL DISEASE IN PREGNANCY. II. CORRELATION BETWEEN ORAL HYGIENE AND PERIODONTAL CONDTION. ActaOdontolScand 22: 121-135.

- LOE H, SILNESS J (1963) PERIODONTAL DISEASE IN PREGNANCY. I. PREVALENCE AND SEVERITY. ActaOdontolScand 21: 533-551.

- Hugoson A, Koch G, Göthberg C, Helkimo AN, Lundin SA, et al. (2005) Oral health of individuals aged 3-80 years in Jönköping, Sweden during 30 years (1973-2003). I. Review of findings on dental care habits and knowledge of oral health. Swed Dent. J 29: 125-138.

- Nguyen VH, Messer LB, Robertson JA (2011) Oral health of schoolchildren in rural Vietnam, Part IV. High early childhood caries experience in preschool-aged children. Synopses 47: 4-11.

- Mejàre I, Stenlund H, Julihn A, Larsson I, Permert L (2001) Influence of approximal caries in primary molars on caries rate for the mesial surface of the first permanent molar in swedish children from 6 to 12 years of age. Caries Res 35: 178-185.

- Alm A, Wendt LK, Koch G, Birkhed D (2007) Prevalence of approximal caries in posterior teeth in 15-year-old Swedish teenagers in relation to their caries experience at 3 years of age. Caries Res 41: 392-398.

- Hugoson A, Koch G, Helkimo AN, Lundin SA (2008) Caries prevalence and distribution in individuals aged 3-20 years in Jönköping, Sweden, over a 30-year period (1973-2003). Int J Paediatr Dent 18: 18-26.

- Alm A (2008) On dental caries and caries-related factors in children and teenagers. Swed Dent J Suppl : 7-63, 1p preceding table of contents.

- Alm A, Wendt LK, Koch G, Birkhed D (2008) Oral hygiene and parent-related factors during early childhood in relation to approximal caries at 15 years of age. Caries Res 42: 28-36

Relevant Topics

- Advanced Bleeding Gums

- Advanced Receeding Gums

- Bleeding Gums

- Children’s Oral Health

- Coronal Fracture

- Dental Anestheia and Sedation

- Dental Plaque

- Dental Radiology

- Dentistry and Diabetes

- Fluoride Treatments

- Gum Cancer

- Gum Infection

- Occlusal Splint

- Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

- Oral Hygiene

- Oral Hygiene Blogs

- Oral Hygiene Case Reports

- Oral Hygiene Practice

- Oral Leukoplakia

- Oral Microbiome

- Oral Rehydration

- Oral Surgery Special Issue

- Orthodontistry

- Periodontal Disease Management

- Periodontistry

- Root Canal Treatment

- Tele-Dentistry

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14832

- [From(publication date):

September-2014 - Apr 24, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10210

- PDF downloads : 4622