Review Article Open Access

Older Sami Women Living in the Arctic: A Cultural Background that Breaks with Western Conventions

Gunn-Tove Minde*UIT–The Arctic University, Norway

- *Corresponding Author:

- Gunn-Tove Minde

Associate Professor, UIT–The Arctic University

Norway

Tel: +4795790510

E-mail: gunn-tove.minde@uit.no

Received date: December 07, 2016; Accepted date: January 20, 2017; Published date: January 27, 2017

Citation: Minde G (2017) Older Sami Women Living in the Arctic: A Cultural Background that Breaks with Western Conventions. J Comm Pub Health Nurs 3:155. doi:10.4172/2471-9846.1000155

Copyright: © 2017 Minde GT. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

Abstract

This article is about older Sami women living in the Arctic region in Norway. The Sami are indigenous people of northern Scandinavia and northern Russia; Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. The Sami people have a background that breaks with western traditions. In order to understand their cultural values, beliefs and worldviews anchored in “the living body”, elder care should consider their cultural, ethnic and linguistic distinctiveness. The three older Sami women presented in this text, Maret, Beret and Betty, have lived in close contact with of lige of older Sami women nature throughout their lives. They are particularly sensitive to restrictions that have reduced their freedom and quality of life.

Keywords

Arctic indigenous people; Sami settlement areas; Older women; Cultural background and values.

Introduction

The article is about elderly Sami women living in the Arctic region in Norway. After more than 20 years of research in collaboration with older people, I offer a picture of life among the older Sami women in Arctic regions in Norway. I have limited myself to two Sami lifestyles: the reindeer-herding Sami and the Coastal Sami. Both of whom lived under much the same historical and cultural conditions in Northern Scandinavia. I will describe the lives of three Sami women: Beret, Maret and Betty. Maret and Betty grew up keeping reindeer, which is a husbandry exclusive to Sami. Betty is a Coastal Sami, and she and her husband, like ethnic Norwegian people in the north who live in rural areas and close to nature, have been self-supporting through the exploitation of natural resources.

Today, Maret, Beret and Betty are pensioners, meaning they receive a retirement pension from the State of Norway as Norwegian citizens.

The Sami Settlement Area

The Sami settlement area reaches from the Russian border in the north to inside Hedmark County in the south of Norway. Even with many common denominators that connect the people as one ethnic group, there are also conditions that contribute towards some large variations.

The widespread region has provided opportunities for a number of different industrial adaptations. In the southern Sami areas, reindeer herding has been the dominant industry. In the fjords and communities of the north, combinations of agriculture, farm animal husbandry and fishing have been central. Further north, there has been a fisherman-farmer adaptation as well as freshwater fishing, extensive use of resources in outlying fields including hunting, berry picking, forestry and reindeer herding. In inner Finnmark, a county in the extreme north-eastern part of Norway, there is both a settled Sami population and a nomadic, reindeer-herding population. Maret and Beret belong to the nomadic lifestyle, moving to the coast during the summer months. Betty’s lifestyle is that of the settled Coastal Sami.

Method

This article started as a multimedia production together with the photographer Grete A. Kvaal. The multimedia production was titled “Elderly women living in the Arctic” and was presented at the 7th Interdisciplinary Congress of Women in Tromsø, Norway. The project has since developed from a multimedia production to a full-scale article. Informing this article is material collected during my doctorate project, which was titled “The Needs of elderly Sami and life quality in Coastal Sami regions in the Arctic”. I collected my data over a period of two years. Of the 40 number of Sami women previously interviewed, Maret, Beret and Betty were selected for inclusion in this article because having representative Sami lifestyles.

Hierarchy of the Basis of Existence

When the reindeer-herding Sami came to the coast during the summer, they met the Coastal Sami – where the elderly among the Coastal Sami had a common language with the people of the plains. In this way, the children learned a little of the language and experienced fellowship. Even if the people of the plains and the coast lived differently, the experience enriched the population rather than diminished it. They shared a language, a respect and knowledge of the totality of nature. Therefore, there existed few differences between the Coastal and the reindeer-herding Sami. The Coastal Sami respected the long-standing ancestral customs from the outlying group, and were taught to show respect and sensitivity regarding their knowledge [1].

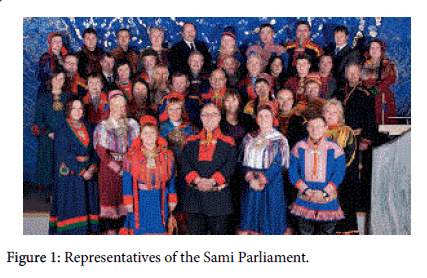

Today, many elderly Sami do not have the same level of basic trust for differences in Sami approaches for instance, many express scepticism towards the Sami Parliament and its underlying agencies. They perceive the Sami Parliament system to be a new public agency that will impose new rules on the people. The Sami Parliament is subordinate to the Norwegian Parliament, and therefore is not an equal agency (Figure 1).

The elderly have also reacted negatively to the way in which socalled Sami elites assert their rights, which the elderly feel is counter to showing equal respect, responsibility and authority for all life and not just for the lives of a few people. For example, with the support of the Sami elite, the Norwegian Parliament passed the Sami Act from 1987 and the new Reindeer Herding Act from 2007 [2]. In the condition for these two Acts, which restricted Sami rights to the smallest reindeerherding units? Standardisation, restriction of area of industry (outlying fields), and privileges for the interests of some in preference to common interests are some of the consequences of not adapting the Act to include the elderly’s respect for interaction with nature and mutual freedom.

Integration in the national state, together with the building of the Sami nation, has created new mechanisms of social and cultural differentiation. For many, including Maret, Beret and Betty, this is experienced as painful and filled with conflict, because the hierarchic divisions have also reached into the Sami communities. For many Sami, the goal is to be allowed to be themselves and to pass on their ancestors' inheritance of equality and totality via traditional activities. Other Sami have chosen jobs and lifestyles that do not differentiate them from Norwegians. They are fighting for a place in the hierarchy on an equal level with the Norwegian population without solving the problem of the elderly Sami people's principle of reciprocity in a modern context.

Maret, Beret, Betty and science

Naturalist Darwin was engrossed in explaining the origins of man in terms of hierarchy, where the principle is the superiority and inferiority of life [3]. In conflict, this means kill or be killed, bring something else down or be brought down you. In practice, this means inequality for all life, and is a part of the national as the international statutory framework. Later, Darwin's teachings were developed and systematised by Herbert Spencer [4], who believed that the theory Darwin developed for the origin and development of biological species could also be extended to the general, that is, social life, art and science (social Darwinism).

Through a long life in close association with nature and people, Maret, Beret and Betty know that all life is equal. This is something they know, and not something they think they know. This knowledge is also the complete opposite of what Darwin and Spencer asserted. People are given life so that all life can be strengthened and given opportunities for growth and fertility, and not so that some life will be weakened and marginalised. Throughout generations, they have learned that nature cannot be exploited from an economic and onesided way of thinking that drains off the basis of life. Among other things, reindeer herding depends upon a sustainable development, where people and nature interact with each other.

Maret, Beret and Betty as culture carriers

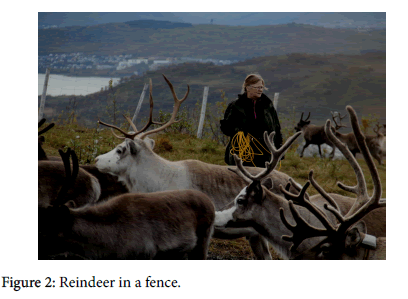

Maret, Beret and Betty have had –and still have– roles as preservers and carriers of culture in the Sami community. Despite the fact that Maret and Beret are old, they participate in reindeer fencing. Their activity around reindeer fencing is a fellowship and is something much more than the act itself. They participate together with the rest of the family and constitute a part of the total household that is based upon an extended family system. They have a function and share the family's experiences, maintain the continuity for the industry and are important for the identity. In this way, within the activity of reindeer fencing, the grandchildren witness a natural, central view of the reciprocal love relationship between their grandparents and the animals [5] (Figure 2).

Betty lives alone in spite of her old age – and manages on her own in her home and with her daily activities. Her close proximity to the farm, farm animals and her son provides the best conditions for preserving memories both from an ancient time and that determine who she is. She feels content at home, and gets her dinner every day from the community health care centre. She sometimes muddles things up a bit and talks a great deal about the past. If she meets people who treat her like a person, she extends herself. By living near her son and daughterin- law, she is “an institution” herself, communicating cultural heritage to her family, relatives and neighbours who visit the farm. She will not be stuck away in an elderly home, she said. Old age is also one of life's most important stages, because its vulnerability unveils our ability for reciprocal love and care (Figure 3).

The spiritual and religious life

In Sami communities, the belief in powers beyond the control of man was very much alive. Throughout childhood, children were taught to believe in certain superhuman principles that tied man and nature together. This viewpoint of the individual and society created a framework around respect for reciprocity in everyday life where most people shared a foundation of common experience which created a community that reached far beyond the family and neighbourhood. Maret, Beret and Betty have a faith where the Læstadian interpretation of the Bible and value basis is an internalised part of their practice. Values such as ordinary good manners, care, concern, honesty, and compassion and respect for all human life are values that are symbolised through their behaviour. Beret, Maret and Betty have not always been Christian. Living in close association with nature has developed that which is the essential in life and the conditions for joy in life and the development of life. They live in tempo with their needs and what they feel is right, which is in complete conformity with man and nature. They are one with nature both with the nature outside and with the nature of their deepest selves. This overall understanding of man's existence and nature has shaped them into humble yet proud women.

Neither are they afraid of death and they does not believe that man goes to hell, as espoused by Christianity. "It is earth that is hell just look at all the wars in the world today", says Beret with Maret agreeing.

Traditions associated with disease and health

Medical school traditions are given domination over local knowledge about healing. For example, for treatment, Betty must go to a hospital which is an hour-and-a-half away by taxi. Despite a long Sami tradition of healing arts, this knowledge about disease and health was categorised as ignorance quackery, superstition, faith and magic, while newly-won information was called knowledge and/or science. In 1936, the Norwegian Parliament passed the Quackery Act [2], the purpose of which was to reduce the activities of practitioners of folk medicine; Medical Officers of Health would now report quackery in their reports. The Act forbids both practitioners and users of folk medicine to use and develop the traditional knowledge. For Beret, Maret and Betty, folk medicine is not superstition, ignorance or magic, but a highly conscious tradition and part of a field of culture and knowledge. They use both the medical doctor and the local healer without pitting one against the other.

Old age

People who live in close contact with nature throughout their lives, like Maret, Beret and Betty, are particularly sensitive to restrictions that reduce that life. This has a universal character. They say that they experienced Norwegianising as a restraint. The restrictions included, for example, that they were not allowed to speak Sami at institutions that were dominated by Norwegian laws and regulations, for instance schools. Symbols that admonished people about "Saminess" were sanctioned in every way, both locally and in larger public institutions. The pain that this good intention caused was internalised as silence pretty much all the way up until the present. This pain may be reactivated the day they end up in an institution (a hospital or a home for the elderly). Their destiny is handed over to a public system that defines them as inferior clients, to people who do not consider their cultural, ethnic and linguistic distinctiveness [6]. Neither are their needs attended to as to where the institution is located (a Sami area) nor the ethnic background of the employees. The principle of the law of hierarchy does not provide them with a care that considers them special and unique as Sami women – it will be as it is for all elderly who end up in institutions, regardless of gender and ethnicity. Beret, Maret and Betty have embodied memories about a non-hieratic practice. In their everyday life, they lived in reciprocal freedom with both nature and spouse. In this freedom, they could decide over their own lives. The strong experiences and memories from this equal life and their present, unequal status as inferior clients, leads to a painful conflict that reduces and wears out the joy of life for Maret, Beret and Betty.

Conflict of Interest and Funding

The author has not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct the study

References

- Minde GT (1999) I begynnelsen var livet. Global costs- Life in change: Gender challenges. In: Gerrard S, Balsvik RR (eds.) Kvinnforsk`s skriftserie, Center for Women's Studies, UITâÂ?Â?The Arctic University.

- Reindriftloven (2007) The reindeer herding.

- Darwin C (1859) On the origin of species by means of natural selection.

- Rumney J (2009) Herbert SpencerâÂ?Â?s sociology. A study of social theory, London: Aldine Transaction.

- Kvaal Grete A (2001) Karen Anna og hennes Siida. Oslo: Pax Forlag.

- Minde GT (2016) Open the medical room: How indigenous patientsâÂ?Â? cultural knowledge appears in the meeting with the health care providers during the rehabilitation process. In: Hart MA, Burton AD, Hart K, Rowe G, Halonen D, et al. (eds.) International Indigenous Voices in Social Work. Cambridge publishing, United Kingdom.

Relevant Topics

- Chronic Disease Management

- Community Based Nursing

- Community Health Assessment

- Community Health Nursing Care

- Community Nursing

- Community Nursing Care

- Community Nursing Diagnosis

- Community Nursing Intervention

- Core Functions Of Public Health Nursing

- Epidemiology

- Epidemiology in community nursing

- Health education

- Health Equity

- Health Promotion

- History Of Public Health Nursing

- Nursing Public Health

- Public Health Nursing

- Risk Factors And Burnout And Public Health Nursing

- Risk Factors and Burnout and Public Health Nursing

Recommended Journals

- Epidemiology journal

- Global Journal of Nursing & Forensic Studies

- Global Nursing & Forensic Studies Journal

- global journal of nursing & forensic studies

- journal of community medicine& health education

- journal of community medicine& health education

- Palliative Care & Medicine journal

- journal of pregnancy and child health

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3935

- [From(publication date):

February-2017 - Dec 20, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 3265

- PDF downloads : 670