Editorial Open Access

Obesity and Sexual Abuse in American Indians and Alaska Natives

James A Levine1,2, Shelly K McCrady-Spitzer1 and William Bighorse11Department of Endocrinology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

2Obesity Solutions, Mayo Clinic Arizona and Arizona State University, Scottsdale, AZ, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- James A Levine

Department of Endocrinology

Mayo Clinic Arizona and Arizona State University

13400-East Shea Blvd, Scottsdale, AZ-85259, USA

Tel: 480-301-4524

E-mail: levine.james@mayo.edu

Received Date: August 26, 2016; Accepted Date: August 27, 2016; Published Date: August 29, 2016

Citation: Levine AJ, McCrady-Spitzer SK, Bighorse W (2016) Obesity and Sexual Abuse in American Indians and Alaska Natives. J Obes Weight Loss Ther 6:e119. doi:10.4172/2165-7904.1000e119

Copyright: © 2016 Levine AJ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Obesity & Weight Loss Therapy

Abstract

Mainstream American culture frequently minimizes the prevalence and significance of sexual abuse. Unfortunately, this denial of extensive victimization of women is also present in many underserved populations. In June 2007, Amnesty International released its report on sexual abuse in indigenous women, which states that, “One in three Native American or Alaska Native women will be raped at some point in their lives. Most do not seek justice because they know they will be met with inaction or indifference.” This report highlighted an infrequently discussed issue namely, very high levels of sexual abuse in Native American and Alaska Native women. The relationship between sexual abuse and obesity has been delineated in several studies; overall about one quarter to one half of women with high levels of obesity has been sexually abused and it has been postulated that weight-gain serves as an adaptive response for many survivors of sexual abuse. It is also well known in Native American and Alaskan Native women that there is a high prevalence of obesity (about 40% greater than the population average) and that this obesity is associated with a many-fold greater risk of diabetes and increased risks of hypertension, cancer and cardiovascular disease. The link between the concomitantly high rates of sexual abuse and obesity in this population may or may not be partial causality but the issue is nonetheless important. If approaches are to succeed in reversing the trend of increasing levels of obesity in Native American and Alaskan Native women, the high prevalence of sexual abuse will need to be specifically and comprehensively addressed.

Keywords

Obesity; Sexual abuse; Native american

Editorial

Several minority populations in the United States have been identified that have greater rates of obesity than the Caucasian population [1]. Also, some of these populations are more prone to the complications of obesity such as to diabetes and hypertension [2,3]. One such minority group is American Indians and Alaskan Natives who not only have high obesity rates but also particularly high rates of diabetes [4,5]. Federal agencies and expert panels describe the concept of targeted weight-loss interventions [6-8] for such populations in accordance with indigenous culture [9] and local factors in order to mitigate the heightened health risks.

The notion of “targeted interventions” for obesity stems from the assertion that either (a) specific populations have unique biological and/or environmental risk factors for obesity and the associated complications or (b) the appropriateness and effectiveness of intervention strategies for prevention or treatment vary for different populations. An example of a biological risk factor might be a genetic predisposition to develop diabetes in association with obesity [10] and an example of an environmental factor that predisposes a specific population to obesity is the physical environment that houses such a population (i.e.; “the concrete jungle” or poor access to healthy food and spaces that facilitate physical activity)[11].

Another environmental or societal factor that has been linked to obesity is sexual abuse [12-14]. A history of sexual abuse is frequently associated with obesity in women (the association does exist for men also [15]); when the data from several large surveys are coalesced, the theme is clear; about two thirds of female patients seeking treatment for obesity will have some lifetime history of prior abuse (emotional, physical or sexual) [16,17] and in approximately one third they will report a history of prior lifetime sexual abuse specifically [15,18-23]. In a prospective study of 173 female children, half of whom had experienced substantiated childhood sexual abuse, the abused female subjects were 2.9 times more likely to have obesity by young adulthood (age 20-27) than demographically-matched controls (P=0.009)[24].

Several possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain this relationship between obesity and being the victim of sexual abuse [25]. One possible mediating mechanism is the higher prevalence of mood disorders found in survivors of abuse. Depression is related to poor outcome from obesity treatment [26] and numerous surveys have demonstrated that survivors of abuse are more pre-disposed to depression compared to those who deny a history of abuse [27-29]. A second hypothesis focuses on a possible relationship between abuse survivorship and eating disordered symptoms. Several studies have found that eating disorders are more prevalent in survivors of abuse [30], and in terms of obesity, that many obese individuals with binge eating disorder are survivors of childhood sexual abuse [19,31]. A third premise that has been examined is the viewpoint of obesity as an adaptation to being the victim of abuse.

Patients’ self-reports and evaluations suggest that the link between sexual abuse and obesity includes factors such as self-loathing [32] and the desire to create a sexually-protective barrier for themselves [33,34]. In support of this premise, it has been reported that for some women with a history of sexual abuse, weight loss may trigger symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, thereby making weight loss problematic [35].

Although, there may be a well-documented association between obesity and sexual abuse (we need to remember that there are many abused women who do not become obese) [36], what is unknown at this time is how to successfully treat obese individuals who have been sexually abused [16]. Survivors of sexual abuse may be at risk for a mood disorder [37], posttraumatic stress disorder [38-40] or even psychiatric hospitalization [41] with weight loss intervention, prompting some researchers to begin to explore the possible benefits of addressing survivorship issues to render weight loss most efficacious [18,22,35,42]. Clearly further research is needed to explore how to tailor weight loss interventions for survivors of childhood sexual abuse.

The landmark 2007, Amnesty International report was entitled, ”The Maze of Injustice – the failure to protect indigenous women from sexual violence in the USA” [43] and documents astonishingly high levels of sexual violence committed against Native American and Alaskan Native women. It is noted that Native American and Alaskan Native men are also physically and sexually abused but the prevalence rates are about four-fold less [44]. Prior to this report, US Department of Justice data [45] had documented that one in three Native American and Alaskan Native women are likely to be raped or sexually assaulted in their lifetime. Similarly, the survey recently conducted by Yuan and colleagues [46] in 1,368 people from six Native American tribes, suggested that 45% reported have been physically assaulted and 14% to have been raped. These statistics, however harrowing, are likely to be gross underestimates of the problem the Amnesty International report suggests; On one reservation, for example, “many of the women who agreed to be interviewed, could not think of any native women within their community who had not been subjected to sexual violence”.

The failure to document and halt sexual abuse in Native American and Alaskan Native communities (in reservations and in nonreservation communities) occurs for several reasons that are detailed in the Amnesty International report [43]. First, there are no standardized federal procedures for gathering the data; for example the US Department of justice audit recommended, “Encourage law enforcement agencies, regardless of investigative jurisdiction, to report crimes committed in Indian country to the FBI, for inclusion in the Uniform Crime Report” [47].

Second, women do not feel that reporting these issues will precipitate a response; this is in part because of under-policing but also because of poor cooperation between the tribal, state and federal legal systems. Third, sexual assault forensic examinations are often unavailable or of inadequate quality because of limitations both in training and staffing of the Indian Health Service. Fourth, there is insufficient support for victims either medically or psychologically. Fifth, there is poor accountability so that a victim rarely discovers the result of their report. Sixth, there are underlying societal issues such as racism (most of the sexual assaults are committed by non-natives [43]), poverty and social marginalization. Overall, being the victim of sexual violence has become commonplace for Native American and Alaskan women. The etiology of these disparities may not be substantively different from other populations exposed to multigenerational trauma [12] and include multiple social determinants of health such as discrimination, poverty, a physical environment that does not facilitate healthiness, and lack of health equity following multigenerational trauma. Other inequities are important too such as in education (historically, federally sanctioned boarding schools [48,49] and currently educational inequity [12]), social capital, housing and access to healthcare access.

As targeted approaches are designed to reverse obesity in Native American and Alaskan Native people [50-53], violence committed towards women cannot be ignored as the two issues are likely to be inexorably linked. Reversing obesity can only succeed in an environment where the basic human rights of individuals are respected. The link between the concomitantly high rates of sexual abuse and obesity in this population do not need to be causal for the issue to be important. It is likely that the high prevalence of sexual abuse in Native American and Alaskan Native women will need to be addressed if targeted obesity programs are to succeed in this population.

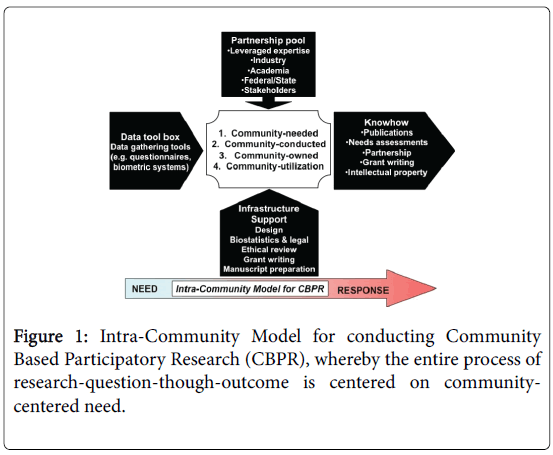

What to do? While many communities and scholars attempt interdisciplinary projects, outcomes are often disappointing because one partner predominates, contributors fail to establish a common language and shared objectives, or the venture fails to establish a truly shared process to meet the community’s needs. Successful programs to address obesity and sexual abuse in American Indians and Alaska Natives necessitate fostering an interdisciplinary environment whereby all participants contribute equitably toward common goals. We have suggested an Intra-Community Model for conducting Community Based Participatory Research (Figure 1), whereby the entire process of research-through-outcome is centered on the needs of the community. While self-empowerment is critical for a person’s success to deal with trauma or obesity [54,55], so too community empowered is the key to redressing community-linked health disparities associated with trauma, obesity and chronic disease.

Acknowledgements

The assistance and critical review of Dr J Kaur is acknowledged.

Grants: Supported by grants DK56650, DK63226, DK66270, DK50456 (Minnesota Obesity Center) and RR-0585 from the US Public Health Service and by the Mayo Foundation.

References

- Shrestha SS, Thompson TJ, Kirtland KA, Gregg EW, Beckles GL, et al. (2016) Changes in Disparity in County-Level Diagnosed Diabetes Prevalence and Incidence in the United States, between 2004 and 2012. PLoS One 11: p.e0159876.

- Cheung BM, Thomas GN (2007) The metabolic syndrome and vascular disease in Asia. CardiovascHematolDisord Drug Targets 7: 79-85.

- Chiu YF, Chuang LM, Kao HY, Ho LT, Ting CT, et al. (2007) Bivariate genome-wide scan for metabolic phenotypes in non- diabetic Chinese individuals from the Stanford, Asia and Pacific Program of Hypertension and Insulin Resistance Family Study. Diabetologia 50: 1631-1640.

- Kurian AK, Cardarelli KM (2007) Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review. Ethn Dis 17: 143-152.

- Doshi SR, Jiles R (2006) Health behaviors among American Indian/Alaska Native women, 1998-2000 BRFSS. JWomens Health (Larchmt) 15: 919-927.

- Bronner Y, Boyington JE (2002) Developing weight loss interventions for African- American women: elements of successful models. J Natl Med Assoc94: 224-235.

- Bader DS, Maguire TE, Spahn CM, O'Malley CJ, Balady GJ (2001) Clinical profile and outcomes of obese patients in cardiac rehabilitation stratified according to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria. J CardiopulmRehabil21: 210-217.

- Harvey PW, Steele J, Bruggemann JN, Jeffery RW (1998) The development and evaluation of lighten up, an Australian community-based weight management program. Am J Health Promot13: 8-11.

- Sinley RC, Albrecht JA (2016) Understanding fruit and vegetable intake of Native American children: A mixed methods study. Appetite 101: 62-70.

- Comuzzie AG, Allison DB (1998) The search for human obesity genes. Science 280: 1374-1377.

- Levine JA (2004) Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). Nutr Rev 62: S82-97.

- Liu DM, Alameda CK (2011) Social determinants of health for Native Hawaiian children and adolescents. Hawaii Med J 70: 9-14.

- AfifiTO,MacMillan LH, Michael Boyle, Kristene Cheung, Tamara Taillieu, et al. (2016) Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Rep, 2016. 27: 10-18.

- Imperatori C,Innamorati M, Lamis DA, Farina B, Pompili M et al.(2016) Childhood trauma in obese and overweight women with food addiction and clinical-level of binge eating. Child Abuse Negl58: 180-190.

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Brody M, Toth C, Burke-Martindale CH, et al. (2005) Childhood maltreatment in extremely obese male and female bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Res 13: 123-130.

- Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V (2002) Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J ObesRelatMetabDisord26: 1075-1082.

- Kimerling R, Alvarez J, Pavao J, Kaminski A, Baumrind N (2007) Epidemiology and consequences of women's revictimization. Womens Health Issues 17: 101-106.

- Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH (2006) Relation of childhood sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment to 12-month postoperative outcomes in extremely obese gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg 16: 454-460.

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM (2001) Childhood psychological, physical, and sexual maltreatment in outpatients with binge eating disorder: frequency and associations with gender, obesity, and eating-related psychopathology. Obes Res 9: 320-325.

- Aaron DJ, Hughes TL (2007) Association of childhood sexual abuse with obesity in a community sample of lesbians. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15: 1023- 1028.

- Oppong BA, Nickels MW, Sax HC (2006) The impact of a history of sexual abuse on weight loss in gastric bypass patients. Psychosomatics 47: 108-111.

- Larsen JK, Geenen R (2005) Childhood sexual abuse is not associated with a poor outcome after gastric banding for severe obesity. Obes Surg 15: 534-537.

- Jia H, Li JZ, Leserman J, Hu Y, Drossman DA (2004) Relationship of abuse history and other risk factors with obesity among female gastrointestinal patients. Dig Dis Sci49: 872-877.

- Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, Putnam FW (2007) Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: a prospective study. Pediatrics 120: e61-67.

- Gustafson TB, Sarwer DB (2004) Childhood sexual abuse and obesity. Obes Rev 5: 129-135.

- Clark MM, Raymond Niaura, Teresa K King, Vincent Pera(1996) Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav 21: 509-513.

- Gustafson TB, Lauren M Gibbons, David B Sarwer, Canice E Crerand, Anthony N Fabricatore, et al. (2006) History of sexual abuse among bariatric surgery candidates. Surg ObesRelat Dis 2: 369-374.

- Wadden TA, Gibbons LM, Sarwer DB, Crerand CE, Fabricatore AN, et al. (2006) Comparison of psychosocial status in treatment-seeking women with class III vs. class I-II obesity. Surg ObesRelat Dis 2: 138-145.

- Pribor EF, Dinwiddie SH (1992) Psychiatric correlates of incest in childhood.Am J Psychiatry 149: 52-56.

- Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Thompson KM, Redlin J, et al. (2001) Eating disturbance and sexual trauma in childhood and adulthood. Int J Eat Disord 30: 401-412.

- Wonderlich SA,Rosenfeldt S, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG, et al. (2007) The effects of childhood trauma on daily mood lability and comorbid psychopathology in bulimia nervosa. J Trauma Stress 20: 77-87.

- Weiss F (2004) Group psychotherapy with obese disordered-eating adults with body- image disturbances: an integrated model. Am J Psychother58: 281-303.

- Wiederman MW, Sansone RA, Sansone LA (1999) Obesity among sexually abused women: an adaptive function for some? Women Health 29: 89-100.

- Felitti VJ (1993) Childhood sexual abuse, depression, and family dysfunction in adult obese patients: a case control study. South Med J 86: 732-736.

- King TK, Clark MM, Pera V (1996) History of sexual abuse and obesity treatment outcome. Addict Behav 21: 283-290.

- Adolfsson B, Elofsson S, Rössner S, Undén AL (2004) Are sexual dissatisfaction and sexual abuse associated with obesity? A population-based study. Obes Res 12: 1702-1709.

- Hwang CS, Mandrup S, MacDougald OS, Geiman DE, Lane MD (1996) Transcriptional activation of the mouse obese (ob) gene by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha. ProcNatlAcadSci USA 93: 873-877.

- Masho SW, Ahmed G (2007) Age at sexual assault and posttraumatic stress disorder among women: prevalence, correlates, and implications for prevention. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 16: 62-71.

- Saylors K, Daliparthy N (2006) Violence against Native women in substance abuse treatment. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res 13: 32-51.

- Aspelmeier JE, Elliott AN, Smith CH (2007) Childhood sexual abuse, attachment, and trauma symptoms in college females: the moderating role of attachment. Child Abuse Negl31: 549-566.

- Clark MM, Hanna BK, Mai JL, Graszer KM, Krochta JG, et al.(2007) Sexual abuse survivors and psychiatric hospitalization after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 17: 465-469.

- Roberts SJ (1996) The sequelae of childhood sexual abuse: a primary care focus for adult female survivors. Nurse Pract21: 49-52.

- Amnesty_International (2007) The Maze of Injustice - the failure to protect indigenous women from sexual violence in the USA.

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Novins DK, Beals J, Manson SM, et al. (2005) Childhood physical and sexual abuse and subsequent depressive and anxiety disorders for two American Indian tribes. Psychol Med 35: 329-340.

- Perry SW (2004) American Indians and Crime, in A BJS Statistical profile 1992-2002. US Department of Justice: Washington Dc.

- Yuan NP, Koss MP, Polacca M, Goldman D (2006) Risk factors for physical assault and rape among six Native American tribes. J Interpers Violence 21: 1566-1590.

- United States Department of Justice (1996) Audit Report 96-16

- Enns RA (2009) But what is the object of educating these children, if it costs their lives to educate them?": federal Indian education policy in western Canada in the late 1800s. J Can Stud 43: 101-123.

- Evans-Campbell T, Walters KL, Pearson CR, Campbell CD (2012) Indian boarding school experience, substance use, and mental health among urban two-spirit American Indian/Alaska natives. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 38: 421-427.

- Godin K, Leatherdale ST, Elton-Marshall T (2015) A systematic review of the effectiveness of school-based obesity prevention programmes for First Nations, Inuit and Metis youth in Canada. ClinObes5: 103-115.

- Towns C, Cooke M, Rysdale L, Wilk P (2014) Healthy Weights Interventions in Aboriginal Children and Youth: A Review of the Literature. Can J Diet Pract Res 75: 125-131.

- Pahwa P, Sylvia Abonyi, ChandimaKarunanayake, Donna C Rennie, Bonnie Janzen, et al. (2015) A community-based participatory research methodology to address, redress, and reassess disparities in respiratory health among First Nations. BMC Res Notes 8: 199.

- Sabin JA, Moore K, Noonan C, Lallemand O, Buchwald D (2015) Clinicians' Implicit and Explicit Attitudes about Weight and Race and Treatment Approaches to Overweight for American Indian Children. Child Obes11: 456-465.

- Struzzo P, Fumato R, Tillati S, Cacitti A, Gangi F, et al. (2013) Individual empowerment in overweight and obese patients: a study protocol. BMJ Open 3: 5

- Tucker CM, Butler A, Kaye LB, Nolan SE, Flenar DJ, et al. (2014) Impact of a Culturally Sensitive Health Self-Empowerment Workshop Series on Health Behaviors/Lifestyles, BMI, and Blood Pressure of Culturally Diverse Overweight/Obese Adults. Am J Lifestyle Med 8: 122-132.

Relevant Topics

- Android Obesity

- Anti Obesity Medication

- Bariatric Surgery

- Best Ways to Lose Weight

- Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Child Obesity Statistics

- Comorbidities of Obesity

- Diabetes and Obesity

- Diabetic Diet

- Diet

- Etiology of Obesity

- Exogenous Obesity

- Fat Burning Foods

- Gastric By-pass Surgery

- Genetics of Obesity

- Global Obesity Statistics

- Gynoid Obesity

- Junk Food and Childhood Obesity

- Obesity

- Obesity and Cancer

- Obesity and Nutrition

- Obesity and Sleep Apnea

- Obesity Complications

- Obesity in Pregnancy

- Obesity in United States

- Visceral Obesity

- Weight Loss

- Weight Loss Clinics

- Weight Loss Supplements

- Weight Management Programs

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 12349

- [From(publication date):

August-2016 - Jul 14, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11354

- PDF downloads : 995