Research Article Open Access

Not another Complaint!

Matthew Megson1, Christina A W Macano1*, Sian Davies2, Zainab Zafar3, Sitaramachandra M Nyasavajjala1 and Vittal S R Rao31Department of Upper GI Surgery, Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham Heartlands Campus, Bordesley Green, Birmingham, B9 5SS, UK

2Department of Upper GI, New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton WV10 0QP, UK

3Department of Upper GI Surgery, University Hospitals of North Midlands, Newcastle Rd, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire ST4 6QG, UK

- *Corresponding Author:

- Christina A W Macano

Department of Upper GI Surgery

Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust

Birmingham Heartlands Campus, Bordesley

Green, Birmingham, B9 5SS, UK

Tel: 07816503412

E-mail: christinamacano@hotmail.com

Received date: February 07, 2017; Accepted date: February 22, 2017; Published date: February 27, 2017

Citation: Megson M, Macano CAW, Davies S, Zafar Z, Nyasavajjala SM, et al. (2017) Not another Complaint! J Gastrointest Dig Syst 7:491. doi: 10.4172/2161-069X.1000491

Copyright: © 2017 Megson M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

Introduction: Surgical patient complaints can be used to identify deficiencies within healthcare provision. The Francis report highlighted that at Mid-Staffordshire multiple complaints had demonstrated the problems at the trust. The number of complaints in the NHS is still rising yearly. Review of patient complaints by clinicians could highlight areas of clinical care requiring improvement. Methods: A University hospitals surgical patient complaints reported to Patient Advice and Liaison Service from 2011-2015 were reviewed. Complaints were classified into: Attitude of Staff, General Nursing, Clinical Treatment, Admission transfer and discharge arrangements, Inpatient appointment delay/cancellation, Consent to Treatment, Communication, Aids and appliances, Other, Outpatient appointment delay/cancellation, Hotel Services and Records. Results: The number of patient complaints within the NHS is increasing. 869 complaints were received. It is often reported that communication is the basis of most complaints but “All aspects of Clinical Treatment” was the most common complaint category, constituting of >50% of complaints. The other common categories were attitude of staff, admission Delay/Discharge and appointments Inpatients/Outpatient. Within clinical treatment the most frequent issues were suitability of treatment followed by delay in providing results. Conclusion: It is often reported that communication is the basis of most complaints however, in this study the commonest complaint related to the suitability of the treatment. This may indicate an underlying problem with communication regarding management decisions, specifically explanation and consent. Clear communication and improving patient engagement in decision could yield dramatic decreases in complaints

Keywords

Patient complaints; Surgical complications; Quality of care

Introduction

Patient complaints can provide a valued source of information about patient care and safety within the hospital setting [1]. Most large businesses use a systematic complaints management to improve their service to customers. Analyzing complaints within the NHS can highlight deficiencies within healthcare provision and highlight areas for improvement which would not neccesdsary be identified by other areas of healthcare monitoring such as incident reporting [2] The Francis report [3] at Stafford Hospital highlighted that multiple complaints had already demonstrated the problems at the trust and these were not recognized or deal with. The NHS receives a vast number of complaints in a year, the hospital and community health care related complaints from 2014-2015 numbered 121,000 [3].

This was a 5.7% rise in documented complaints since 2013-2014. The complaints can focus on a diverse set of problems, from car parking to medical negligence. Patients lodge complaints for a variety of reasons from resolving dissatisfaction, to create change, or to prevent future issues [4,5]. One of the reasons for looking at complaints and learning from them is to allow for trainees to prevent and or reduce their future associated patient complaints when they take up responsibility as a consultant. This is particularly important as dealing with a complaint can be costly, will take up valuable resources and can take up a considerable amount of a surgical consultant’s time. There is also some limited evidence to show that high incidence of patient complaints are also associated with adverse surgical outcomes and highlighting these issues early could help improve patient outcomes [6]. Because of the high prevalence and prognostic value of patient complaints, all surgeons should better understand their nature, content, and value.

Educational approaches based on analysis of patient complaints may be useful tools for developing the communication skills and attitudes of surgical trainees and for modifying behaviour in practicing surgeons. The aim of this study was to review reported complaints to the general surgical department to identify any underlying issues/ problems/deficiencies that may be addressed to improve patients' experience and care.

Methods

A retrospective review was performed on all patients complaints to the University Hospital Of North Midlands, Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) team. (this bit is discussion not methodology). These complaints were then classified into the following categories: attitude of staff, general nursing, clinical treatment, admission transfer and discharge arrangements, inpatient appointment delay/cancellation, consent to treatment, communication aids and appliances, outpatient appointment delay/cancellation, hotel services and records, etc. Data was then collated into a database and analysed using PRISM statistical software.

Results

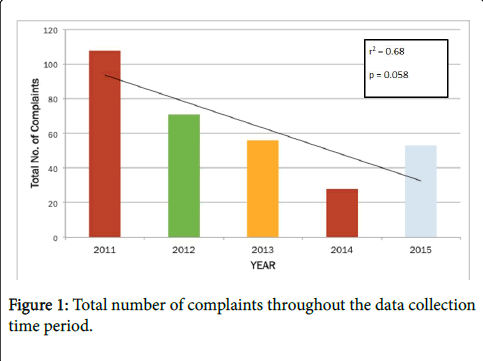

A total of 869 complaints were identified between January 2011 and December 2015 relating to general surgical patients (Figure 1). Over the five-year period the total number of complaints were clearly observed to reduce in number although not statistically significant.

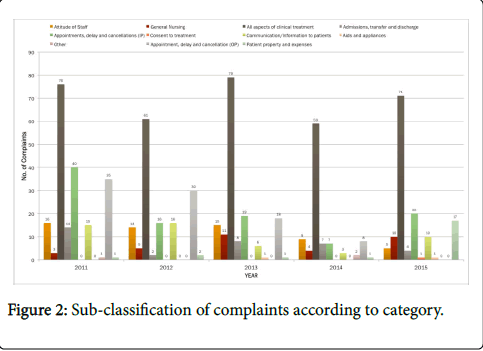

When analysis was performed based on the categories of complaints over the same period consistently the highest number of complaints were focusing on all aspect of clinical treatment (p ≤ 0.05). The most significant reduction in complaints that was observed focused on outpatient appointment delay/cancellation (r2=0.97, CI= -11.07 to -7.33, p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 2). There was also a general reduction seen in complaints focusing on the attitude of staff however, interestingly the number of complaints regarding general nursing appeared to increase, although not statistically significantly (r2=0.31, CI= -2.2 to 4.8, p=0.33). The other categories were consistent over the 5 years.

When analyses was performed on the specific areas of concern relating to clinical treatment the two areas that were clearly of greatest patient concern were suitability of treatment (22%) and diagnosis (12%) (Table 1).

| Complaints | Total No. of Complaints |

| Medication | 14 (4%) |

| Suitability of treatment | 77 (22%) |

| Coordination of services | 5 (1%) |

| Tests, procedures | 18 (5%) |

| Delay in providing results | 28 (8%) |

| Failure to follow agreed procedure | 14 (4%) |

| Delay/Failure of referral process | 15 (4%) |

| Diagnosis | 42 (12%) |

| Unplanned return to theatre | 15 (4%) |

| Observations | 2 (1%) |

| Assessments | 17 (5%) |

| Pain control inadequate | 5 (1%) |

| Wound infection | 6 (2%) |

| Cross body issues | 24 (7%) |

| Falls | 1 (0%) |

| Failure to follow up | 20 (6%) |

Table 1: Complaint percentage among patients.

Discussion

The numbers of patient complaints within the NHS as a whole are increasing. The NHS received 5.7% more written complaints in 2014-2015 compared to 2013-2014 [7]. The analysis of these complaints serves two purposes. Firstly it addresses the individual patients problem and allows solutions to be designed for case-specific complaint. Secondly, if analysis of a large number of complaints happens, it can highlight system-wide issues in patient care [8].

In reality the total number of complaints are very likely to be only a small proportion of those patients who had a less than satisfactory experience. A study in the US showed that more than one third of patients experienced some degree of dissatisfaction with hospital care [9], yet only a minority of these patients actually complained following a dissatisfying experience, and even fewer actually lodged a formal complaint [10]. Despite this limited number of documented complaints, these can still offer a systematic strategy for feedback about health care behaviour and deficiencies.

However, there are problems with solely using patient complaints for the basis of change. We need to consider why patients write complaints; firstly, they do not necessarily represent systematic failure, they do however, represent a single patient’s experience [11]. Secondly, patient complaints are often emotive, written when the patient or family member is angry and distressed, with individual health care professionals being criticized. Thirdly, complaints often concentrate on problems in interactions with healthcare staff [3], leading to the focus of the complaint being subjective (e.g. compassion and dignity) [12]. Lastly, patient complaints will be made without awareness of the wider system pressures influencing care.

It is often reported that communication is the basis of most complaints as in the study by Skalen et al. [13] "the most frequent causes for dissatisfaction were that the healthcare provider 'did not tell the truth' or 'gave insufficient information'", though a larger systematic review of complaints [3] stated that "39% of complaint issues focus on 2 categories, communication and treatment''. Bark et al. [4], concluded that "complaints arose from serious incidents, generally a clinical problem combined with staff insensitivity and poor communication", showing that a lot of these complaints stem from a communication and a clinical issue.

Similarly, in this study, the most common category of complaints related to the suitability of the treatment. This may indicate an underlying problem with communication regarding management decisions, specifically explanation and consent. An example of a complaint due to clinical treatment from our study include; "A Patient underwent surgery to remove lump and had been left with a large scar and large dent at the operation site. The patient was not informed that muscle tissue was being removed". Though this example relates to the clinical treatment they had, it can be seen with hindsight that perhaps better communication, consent process and a discussion about the likely outcomes or possible complications could have potentially prevented this complaint.

This information could be used as a valuable education tool as well. As an educational approach based on analysis of patient complaints may be a useful tool for developing the communication skills and attitudes of medical students and surgical trainees and for modifying those objectionable behaviors in practicing surgeons [8].

Kohanim et al. [14] showed that it matters “who you are” and “where you work”. Their analysis of a large national database showed that those doctors from academic centres, female gender or younger age had statistically significantly higher complaint numbers. Even after adjusting for covariates using multi variable analysis, working at an academic centre was a statistically significant risk factor (adjusted relative risk=1/82; 95% Confidence interval=1.36-2.43; P<0.001). Interestingly, general practitioners had significantly fewer complaints than subspecialists (P<0.05).

There are significant costs that accompany complaints. In the USA, Health care system, the annual cost of "risk management activities" has been estimated at $1.06 billion [15]. This conservative estimate applied only to hospitals, and did not include defense costs or consultants time [16].

In conclusion, although it is often reported that communication is the basis of most complaints, this study highlighted the commonest complaint was related to the suitability of treatment. This may indicate an underlying problem with communication regarding management decisions, specifically explanation and consent. Clear communication and improving patient engagement in decision could yield dramatic decreases in complaints.

Competing Interests Statement

There is no competing interests to declare and no funding to declare.

References

- Donaldson L (2000) An organisation with a memory. Clin Med (Lond) 2: 452-457.

- Levtzion-Korach O, Frankel A, Alcalai H, Keohane C, Orav J, et al. (2010) Integrating incident data from five reporting systems to assess patient safety: making sense of the elephant. JtComm J Qual Patient Saf36: 402-410.

- Francis R (2013) Report of the Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public Inquiry, London.

- Bark P, Vincent C, Jones A, Savory J (1994) Clinical complaints: a means of improving quality of care. Qual Health Care 3:123-132.

- Hsieh SY (2012) An exploratory study of complaints handling and nature. Int J Nurs Practice 18:471-480.

- Catron TF, Guillamondegui OD, Karrass J, Cooper WO, Martin BJ, et al. (2016) Patient complaints and adverse surgical outcomes. Am J Med Qual 31: 415-422.

- http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB18021

- Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J (2014) Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ QualSaf23: 678-689.

- Steiber S, Krowinski W (1990) Measuring and Managing Patient Satisfaction. Chicago, American Hospital Publishing Company pp:11.

- Tax SS, Brown SW (1998) Recovery and learning from service failure. Sloan Manage Rev 40: 75-88.

- Lloyd-Bostock S, Mulcahy L (1994) The social Psychology of making and responding to hospital complaints: an account model of complaint process. Law Policy 16:123-147.

- Reader T, Gillespie A (2013) Patient neglect in healthcare institutions: a systematic review and conceptual model. BMC Health Serv Res 13:156.

- Skalen C, Nordgren L, Annerback EM (2016) Patient complaints about healthcare in a Swedish county: characteristics and satisfaction after handling. Nurs Open 3:203-211.

- Kohanim S, Sternberg Jr P, Karrass J, Cooper W, Pichert JW (2016) Unsolicited patient complaints in Ophthalmology. An Empirical analysis from a large national database. Ophthalmology 123:234-241.

- Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM (2010) National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood) 29: 1569-1577.

- Posner K, Severson J, Domino K (2015) The role of informed consent in patient complaints: Reducing hidden health system costs and improving patient engagement through shared decision making. J Healthc Risk Manag 35: 38-45.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3033

- [From(publication date):

February-2017 - Apr 06, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 2238

- PDF downloads : 795