Commentary Open Access

Neurotoxocariais: A Rare or Neglected Disease?

Alessandra Nicoletti*Department G.F. Ingrassia, Section of Neurosciences, University of Catania, Italy

- *Corresponding Author:

- Alessandra Nicoletti

Department G.F. Ingrassia, Section of Neurosciences

University of Catania, Via Santa Sofia 7895123, Catania, Italy

Tel: 0953782780

Fax: 0953782900

E-mail: anicolet@unict.it

Received date: November 22, 2016; Accepted date: December 12, 2016; Published date: December 14, 2016

Citation: Nicoletti A (2016) Neurotoxocariais: A Rare or Neglected Disease?. J Neuroinfect Dis 7:234. doi: 10.4172/2314-7326.1000234

Copyright: © 2016 Nicoletti A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Neuroinfectious Diseases

Abstract

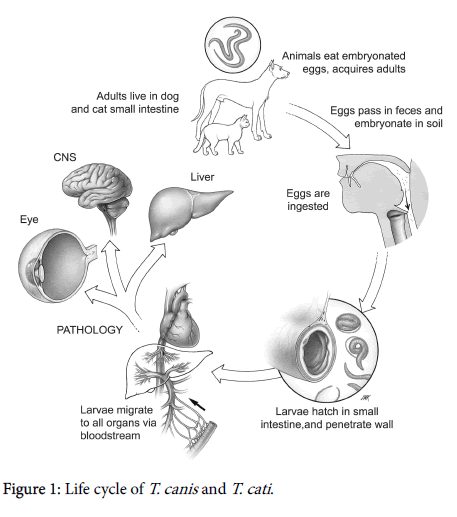

Human toxocariasis is due to the larval stages of the Ascarids Toxocara canis (T. canis ) and probably Toxocara catis , common roundworm of dogs and cats respectively. Among the helminthiasis, toxocariasis is one of the most prevalent worldwide, especially in settings where man-soil-dog relationship is particularly close. Even if it tends to be more prevalent in tropical settings, seroprevalence in western countries ranges from 2.4% to 31.0%.

Commentary

Human toxocariasis is due to the larval stages of the Ascarids Toxocara canis (T. canis ) and probably Toxocara catis , common roundworm of dogs and cats respectively. Among the helminthiasis, toxocariasis is one of the most prevalent worldwide, especially in settings where man-soil-dog relationship is particularly close. Even if it tends to be more prevalent in tropical settings, seroprevalence in western countries ranges from 2.4% to 31.0% [1,2].

Humans are infected by the ingestion of embryonated eggs present in contaminated soil or food. When ingested, embryonated eggs, develop into juvenile larvae that crossing the small intestine migrate to any organ through the circulatory system determining a multisystem inflammatory tissue reactions (Figure 1). Visceral larva migrains (VLM) and ocular larva migrans (OLM) are the most common clinical manifestation, even if asymptomatic infection is common [2]. T. canis larvae can cross the blood brain barrier invading the central nervous system (CNS) and leading to the cerebral toxocariasis or neurotoxocariasis. Autopsy studies of isolated cases, in fact, have revealed T. canis larvae in leptomeninges, gray and white matter of cerebrum, cerebellum, thalamus and spinal cord [3-8]. To date CNS infection in humans is thought to be rare, even if in animal models larvae often migrate to the brain. Neurotoxocariasis can give different neurological disorders such as meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral vasculitis, seizures, headache, but asymptomatic infection are probably common [2]. Neurotoxocariasis is not a frequent diagnosis and it is probably underdiagnosed due to the nonspecific nature of its symptoms (seizures, headache) as well as to the lack of confirmatory diagnostic exams. Diagnosis of neurotoxocariasis, in fact, is based on the detection of high serum and CSF titers of T. canis antibodies and neuroimaging. The clinical and radiological improvement, as well as the normalization of the CSF parameters during antihelminthic therapy, supports the diagnosis. Peripheral and CFS eosinophilia can be also present. However diagnostic criteria are not available and the definitive diagnosis can be reached only by histological examination of infected tissue [2]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with TES-Ag from second stage T. canis larvae [9], is the most common serological assay, that however can give antigenic cross reactivity with different nematode infections [10]. Conversely the use of TES-western blot overcomes the possible cross-reaction [11], but is more expensive and rarely available. Concerning the neuroimaging (CT scan and MRI), neurotoxocariasis is mainly characterized by a granulomatous process leading to reversible white matter lesions and single ringenhancing (“cerebral granuloma”) or multiple ring-enhancing lesions as demonstrated in biopsy-confirmed cases reported in literature [12,13]. However, ring-enhancing lesions are one of the most commonly encountered abnormalities that can be caused by a variety of infectious disease, neoplastic, inflammatory, or vascular diseases [14]. In particular, single enhancing lesions (SEL) represent a common diagnostic dilemma in tropical countries where they are generally due to infectious diseases such as neurocysticercosis (NCC) and tuberculosis. In particular, in T. solium endemic areas the evidence of SEL at neuroimaging is quite common and, according to the widely accepted diagnostic criteria [15], cerebral granuloma disappearing after albendazole or praziquantel treatment is considered one of a major criterion for the diagnosis of NCC. It should be noted that when a single cysticercus granuloma is present, negative serology is frequent due to a lower sensitivity of the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot, considered the gold standard among the serological assays. However, according literature evidences, a SEL disappearing after albendazole treatment [12,13] can be also due to T. canis , thus in this scenario a diagnosis of neurotoxocariasis cannot be entirely ruled out. Regarding the treatment of neurotoxocariasis mebendazole, thiabendazole, albendazole, or diethyl carbamazine have been used with different results, even if is there is a lack of well-controlled studies [16].

Another unsolved issue is the meaning of the association between toxocara seropositivity and epilepsy consistently reported in literature. Early observations have highlighted a high titers of T. canis antibodies among epileptic subjects [17,18]. After these reports, several casecontrol studies have been carried out in different geographic areas, often supporting this possible positive association between epilepsy and T. canis seropositivity [19-32]. This association was also confirmed by a recent meta-analysis including seven cases-control studies, suggesting a possible increased risk of developing epilepsy among people exposed to T. canis infection [32]. Even if seizures have been related to the presence of single or multiple toxocara lesions found in cases described in literature, the epileptogenesis of helminth infections is largely unknown [33-35]. Helminths, in fact, can cause seizures by producing focal lesions, but an antibody-mediated epilpetogenesis cannot be ruled out. As well known, helminths determine a conspicuous immune activation including the production of autoantibodies that, if directed against neuronal antigens, may cause epilepsy [33] From this point of view toxocariasis could also increases the risk of developing epilepsy due to masked mechanisms, despite the absence of detectable focal cerebral granuloma [2].

As matter of the fact, despite toxocariais is considered the most frequent helminthic infection worldwide, neurotoxocariais is largely unknown and diagnosis is rarely sought leading to a possible underestimation of its real burden.

References

- Magnaval JF, Michault A, Calon N, Charlet JP (1994) Epidemiology of human toxocariasis in La Reunion. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 88: 531-533.

- Nicoletti A (2013) Toxocariasis H and B Clin Neurol 114: 217-228.

- Dent JH, Nichols RL, Beaver PC, Carrera GM, Staggers RJ (1956) Visceral larva migrans; with a case report. Am J Pathol 32: 777-803.

- Moore MT (1962) Human Toxocara canis encephalitis with lead encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 21: 201-218.

- Beautyman W, Beaver PC, Buckley JJ, Woolf AL (1966) Review of a case previously reported as showing an ascarid larva in the brain. J Pathol Bacteriol 91: 271-273.

- Schochet SS (1967) Human Toxocara canis encephalopathy in a case of visceral larva migrans. Neurology 17: 227-229.

- Hill IR, Denham DA, Scholtz CL (1985) Toxocara canis larvae in the brain of a British child. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 79: 351-354.

- Mikhael NZ, Montpetit VJ, Orizaga M, Rowsell HC, Richard MT (1974) Toxocara canis infestation with encephalitis. Can J Neurol Sci 1: 114-120.

- De Savigny DH, Voller A, Woodruff AW (1979) Toxocariasis: Serological diagnosis by enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Pathol 32: 284-8.

- Smith H, Holland C, Taylor M, Magnaval JF, Schantz P, et al. (2009) How common is human toxocariasis? Towards standardizing our knowledge. Trends Parasitol 25: 182-188.

- Magnaval JF, Fabre R, Maurieres P, Charlet JP, de Larrard B (1991) Application of the western blotting procedure for the immunodiagnosis of human toxocariasis. Parasitol Res 77: 697-702.

- Xinou E, Lefkopoulos A, Gelagoti M, Drevelegas A, Diakou A, et al. (2003) CT and MR imaging findings in cerebral toxocaral disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 24: 714-718.

- Bachli H, Minet JC, Gratzl O (2004) Cerebral toxocariasis: A possible cause of epileptic seizure in children. Childs Nerv Syst 20: 468-472.

- Schwartz KM, Erickson BJ, Lucchinetti C (2006) Pattern of T2 hypointensity associated With Ring enhancing brain lesions can help to differentiate pathology. Neuroradiology 48: 143-149.

- Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White AC, Tsang VC, Nash TE, et al. (2001) Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology 57: 177-183.

- Magnaval JF, Glickman LT, Dorchies P, Morassin B (2001) Highlights of human toxocariasis. Korean J Parasitol 39: 1-11.

- Woodruff AW, Bisseru B, Bowe JC (1966) Infection with animal helminths as a factor in causing poliomyelitis and epilepsy. Br Med J 1: 1576-1579.

- Critchley EM, Vakil SD, Hutchinson DN, Taylor P (1982) Toxoplasma, toxocara, and epilepsy. Epilepsia 23: 315-321.

- Glickman LT, Cypess RH, Crumrine PK, Gitlin DA (1979) Toxocara infection and epilepsy In children. J Pediatr 94: 75-78.

- Arpino C, Gattinara GC, Piergili D, Curatolo P (1990) Toxocara infection and epilepsy in children: A case-control study. Epilepsia 31: 33-36.

- Nicoletti A, Bartoloni A, Reggio A, Bartalesi F, Roselli M, et al. (2002) Epilepsy, cysticercosis, and toxocariasis: a population-based case-control study in rural Bolivia. Neurology 58: 1256-1261.

- Akyol A, Bicerol B, Ertug S, Ertabaklar H, Kiylioglu N (2007) Epilepsy and seropositivity rates of Toxocara canis and Toxoplasma gondii. Seizure 16: 233-237.

- Nicoletti A, Bartoloni A, Sofia V, Mantella A, Nsengiyumva G, et al. (2007) Epilepsy and toxocariasis: A case-control study in Burundi. Epilepsia 48: 894-899.

- Nicoletti A, Sofia V, Mantella A, Vitale G, Contrafatto D, et al. (2008) Epilepsy and toxocariasis: A case-control study in Italy. Epilepsia 49: 594-599.

- Winkler AS, Blocher J, Auer H, Gotwald T, Matuja W, et al. (2008) Anticysticercal and antitoxocaral antibodies in people with epilepsy in rural Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102: 1032-1038.

- Allahdin S, Khademvatan S, Rafiei A, Momen A, Rafiei R (2015) Frequency of oxoplasma and Toxocara Sp. Antibodies in Epileptic Patients, in South Western Iran. Iran J Child Neurol 9: 32-40.

- Singh G, Bawa J, Chinna D, Chaudhary A, Saggar K, et al. (2012) Association between epilepsy and cysticercosis and toxocariasis: a population-based case-control study in a slum in India. Epilpesia 53: 2203-2208.

- Zibaei M, Firoozeh F, Bahrami P, Sadjjadi SM (2013) Investigation of anti-Toxocara antibodies in epileptic patients and comparison of two methods: ELISA and Western blotting. Epilepsy Res Treat 2013: 156815.

- Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Kleinschmidt I, Wagner RG, Kakooza-Mwesige A, et al. (2013) Prevalence of active convulsive epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa and associated risk factors: Cross-sectional and case-control studies. Lancet Neurol 12: 253-263.

- Kamuyu G, Bottomley C, Mageto J, Lowe B, Wilkins PP, et al. (2014) Exposure to multiple parasites is associated with the prevalence of active convulsive epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e2908.

- Eraky MA, Abdel-Hady S, Abdallah KF (2016) Seropositivity of Toxoplasma gondii and Toxocara spp. in Children with Cryptogenic Epilepsy, Benha, Egypt. Korean J Parasitol 54: 335-338.

- Colebunders R, Mandro M, Mokili JL, Mucinya G, Mambandu G, et al. (2016) Risk factors for epilepsy in Bas-Uélé Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo: A case-control study. Int J Infect Dis 49: 1-8.

- Quattrocchi G, Nicoletti A, Marin B, Bruno E, Druet-Cabanac M, et al. (2012) Toxocariasis and epilepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1775.

- Wagner RG, Newton CR (2009) Do helminths cause epilepsy? Parasite Immunol 31: 697-705.

- Levite M (2002) Autoimmune epilepsy. Nat Immunol 3: 500.

Relevant Topics

- Bacteria Induced Neuropathies

- Blood-brain barrier

- Brain Infection

- Cerebral Spinal Fluid

- Encephalitis

- Fungal Infection

- Infectious Disease in Children

- Neuro-HIV and Bacterial Infection

- Neuro-Infections Induced Autoimmune Disorders

- Neurocystercercosis

- Neurocysticercosis

- Neuroepidemiology

- Neuroinfectious Agents

- Neuroinflammation

- Neurosyphilis

- Neurotropic viruses

- Neurovirology

- Rare Infectious Disease

- Toxoplasmosis

- Viral Infection

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3928

- [From(publication date):

December-2016 - Apr 21, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 3022

- PDF downloads : 906