Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of Breast: A Rare Breast Tumor Worthy of Attention

Received: 06-Apr-2022 / Manuscript No. DPO-22-59754 / Editor assigned: 08-Apr-2022 / PreQC No. DPO-22-59754 (PQ) / Reviewed: 20-Apr-2022 / QC No. DPO-22-59754 / Revised: 25-Apr-2022 / Manuscript No. DPO-22-59754 (R) / Published Date: 02-May-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2476-2024.1000199

Abstract

Background: Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of Breast (NENB) is a rare and under recognized subtype of breast neoplasms. The clinical significance, prognostic risk factors and optimal treatment modalities are limited. This study was focused on clinical and pathological features of 27 NENB cases to improve the understanding of these diseases and to further investigate the behavior of these neoplasms and to provide more factual evidence.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathological features and follow-up data of 27 patients diagnosed with NENB at the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College between February 2003 and February 2015.

Results: The proportion of NENB from all invasive Breast Carcinomas (BC) in our hospital was 0.24% (27/11352). The expression of specific immunohistochemical markers was different: 48.1% cases showed the expression of Chromogranin A (CgA) (13/27), CD56 was positive in 77.8% cases (21/27), the positive rate of INSM1 and Synaptophysin (Syn) were 85.2% (23/27) and 100.0% (27/27). NENB occurred in older patients (median age, 64). 11 cases (40.7%) were well-differentiated NETs and 16 cases (59.3%) were poorly differentiated NEC. In NETs, The positive rate of ER was 10/11 (90.9%), while in NECs, The positive rate of ER was 9/16 (56.3%), On the basis of immunophenotypes, most of NENBs were of the luminal molecular subtype, 6 cases were luminal A and 15 cases were luminal B, 6 cases were Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) and had no HER-2 overexpression subtypes.

Conclusion: NENB more likely occurs in elderly patients. Well-differentiated NETs are more often positive for hormone receptors than poorly differentiated NEC. NENBs are almost negative for HER-2. The combination of INSM1 is an effective supplement and improvement for traditional neuroendocrine markers.

Keywords: Breast; Neuroendocrine neoplasm; Clinicopathologic features; Treatment; Prognosis

Abbreviations

E: Hematoxylin and Eosin; NET: Neuroendocrine Tumor; NEC: Neuroendocrine Carcinoma; OS: Overall Survival; DFS: Disease-Free Survival; Syn: Synaptophysin; CgA: Chromogranin A

Introduction

Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of Breast (NENB) is one of the rarest subtypes of breast tumor. Since neuroendocrine differentiation in Breast Carcinomas (BC) was first described by Feyrter and Hartmann in 1963 [1], various definition and criteria for what constitutes breast neuroendocrine carcinomas have been used. The newest 5th Edition of World Health Organization (WHO) classification of Breast Tumors has moved to a dichotomous classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms in breast in order to become standardized with classifications of other organ system [2]. The most significant feature of this Edition is that it divides NENB into two categories: well-differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumor (NET) and poorly differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (NEC). The latter including highly aggressive small cell carcinomas and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and exclusion of special histologic types (solid papillary carcinoma and hypercellular variant of mucinous carcinoma) [3]. Because the incidence rate of NENB is low and the pathological character is variable, The clinical significance, prognostic risk factors and optimal treatment modalities are limited. This study collected clinical and pathological data of 27 NENB cases in the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College from February 2003 to February 2015 and investigated the clinicopathological features and the prognosis data to improve the understanding of these diseases.

Considering the shortcomings of the current grading system, we hypothesized that 5-hmC IHC could assist in the classification and risk stratification on breast PTs. Herein; we examined 5-hmC levels in the stroma of PTs in relation to the clinicopathologic characteristics. Since cFA comes into a differential diagnosis of benign Phyllodes, it was also included in the study.

Materials and Methods

Study design and patients

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). It was approved by institutional ethics board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College (No. BBMEC-2021088) and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Twenty-seven patients diagnosed with NENB among 11352 patients who underwent surgery for breast cancer at the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College between February 2003 to February 2015 were included in the study. 2 out of 27 cases underwent puncture diagnosis before operation, neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical mastectomy after diagnosis. 4 out of the other 25 cases underwent simple resection and 21 underwent modified radical mastectomy. Review the clinical data, all cases had no history of NEC in other parts before and after surgery.

Specimens were double-blind pathological reviewed by two pathologists. Histological evaluation standards refer to the 5th Edition WHO and TNM staging of breast cancer developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 7th edition). All patients were followed up telephonically using outpatient records.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue sections were employed in each case using a standard protocol. HE-stained sections (4 μm thickness) were re-examined to evaluate the tumor’s histological features and immunohistochemistry were performed with Elivision technique. Antibody details are given in Table 1. The threshold used for positive ER and PR expression was any nuclear labeling 1% or higher [4]. HER-2 immuno reactivity was evaluated on a standardized scale from 0-3 based on the intensity of staining of the cell membrane and the proportion of invasive tumor cells stained. Strong complete staining of the membrane in >10% of tumor cells (score, 3+) was considered positive. Intensity patterns with scores 0-1+ were considered negative, and samples scored as 2+ were further assessed by FISH test. Fluorescence in situ hybridization ratio of 2.0 or more was considered positive for HER-2 gene amplification (Table 1) [5].

| Source | Antibody |

|---|---|

| CK | Monoclonal, AE1/AE3 |

| CKH(34βE12) | Monoclonal, clone34βE12 |

| CK5/6 | Monoclonal, clone D5/16B4 |

| GATA-3 | Monoclonal, clone L50-823 |

| GCDFP-15 | Monoclonal, clone 23A3 |

| mamaglobin | Monoclonal, clone304-1A5 |

| Syn | Monoclonal, cloneSP11 |

| CgA | Monoclonal, cloneSP12 |

| CD56 | Monoclonal,clone56C04 |

| INSM1 | Monoclonal,clone A8 |

| ER | Monoclonal, clone SP1 |

| PR | Monoclonal, clone1A6 |

| HER-2 | Monoclonal, cloneCB11 |

| KI67 | Monoclonal, cloneMIB-1 |

| TTF1 | Monoclonal, cloneSPT24 |

| CDX-2 | Monoclonal, cloneEPR2764Y |

All antibodies were obtained from Maixin Biotech, Inc. (Fuzhou, China), and were ready to use

Table 1: Sources of the antibodies used in the immunohistochemistry analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using Pearson correlation and Fisher’s exact test. Survival curves are constructed with the Kaplan–Meier method. Overall Survival (OS) was defined as the period from diagnosis to recurrence, metastasis, death, or the end of follow- up. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 software for Windows (IBM, New York, USA) and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics

The clinicopathological characteristics of 27 NENB are summarized in Table 2. All were female patients; the median age was 64 years. All patients were presented with a palpable, painless lump in the breast. The tumors were located in the left breast in 18 cases (66.7%) and in the right breast in 9 cases (33.3%). Tumor sizes were determined by gross pathological examination and ranged from 1.2-5.5 cm, the median tumor size was 3.5 cm. Most patients (17/27,62.9%) had T2 disease (tumor size 2.0-5.0 cm) and positive lymph node metastases was reported in 48.1% (13/27) patients (Table 2).

| Clinicopathologic | NENB (%) | Well differentiated | Poorly differentiated | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | (n=27) | NET(n=11) | NEC(n=16) | NET vs NEC |

| Age, years | ||||

| <60 | 11(40.7) | 3 | 8 | 0.237 |

| ≥60 | 16(59.3) | 8 | 8 | - |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||

| ≤2 | 6(22.2) | 2 | 4 | 0.149 |

| 02-May | 17(62.9) | 9 | 8 | - |

| >5 | 4(14.9) | 0 | 4 | - |

| Nodal status | ||||

| Positive | 13(48.1) | 5 | 8 | 0.816 |

| Negative | 14(51.9) | 6 | 8 | - |

| M category | ||||

| M0 | 24(88.9) | 11 | 13 | 0.127 |

| M1 | 3(11.1) | 0 | 3 | - |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I | 3(22.2) | 2 | 1 | - |

| II | 17(55.5) | 8 | 9 | - |

| III | 5(14.8) | 1 | 4 | - |

| IV | 2(7.5) | 0 | 2 | - |

| ER status | ||||

| Positive | 19(70.4) | 10 | 9 | 0.052 |

| Negative | 8(29.6) | 1 | 7 | - |

| PR status | ||||

| Positive | 17(63.0) | 9 | 8 | 0.092 |

| Negative | 10(37.0) | 2 | 8 | - |

| HER-2 status | ||||

| Positive | 0(0) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Negative | 27(100.0) | 11 | 16 | - |

| KI67 | ||||

| <14% | 6(22.2) | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥14% | 21(77.8) | 5 | 16 | - |

Table 2: Clinic pathological features contrast among NENB NET and NEC.

In general observation, 15 cases of tumors were well-defined, expansive growing. The cut surface was gray and white, in which 7 cases were partially or mostly gray and red. The other 12 cases, the boundary was unclear and gray-yellow necrotic areas were visible.

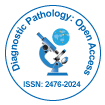

Under microscope, the tumor cells of well-differentiated NET were arranged in Solid Island, trabecular shape or ribbon shape with low to intermediate nuclear grade. Blood sinusoids can be seen between the tumor cell nests. The tumor cells were of medium size and relatively uniform in shape. The nucleus was single, round and had smooth or irregular borders. The cytoplasm was rich and some were more transparent. The mitotic figures were rare.

Poorly differentiated NEC was infiltrative with densely packed hyperchromatic cells with scant cytoplasm. the tumor cells were ovoid to spindled and showed dense chromatin with crush artifact. Mitotic figures were abundant. Primary small cell carcinoma of the breast was histologically similar to lung counterpart, characterized by densely packed hyperchromatic cells with scant cytoplasm (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A. Well-differentiated NET of the breast with trabecular growth pattern (magnification × 100) B. Poorly differentiated NEC with densely packed hyper chromatic cells (magnification × 100) C. Ductal carcinoma in situ components can be seen in NENB (magnification × 100) D. Obvious necrosis can be seen in poorly differentiated NEC (magnification × 100).

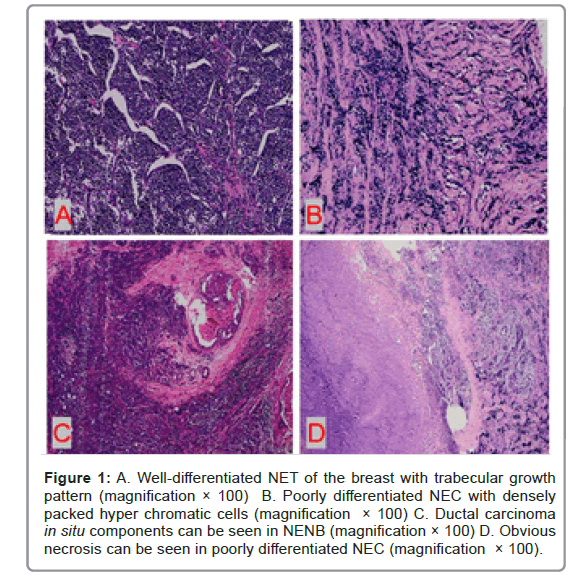

Immunohistochemical profileIn our group, 48.1% cases showed the expression of CgA (13/27), CD56 was positive in 21/27 (77.8%) cases, INSM1 was expressed in 23/27 (85.2%) cases and the positive rate of Syn was 100.0% (27/27).

ER was positive in 19 (70.4%) patients and PR positive in 17 (63.0%) patients. HER-2 was negative in 27 (100.0%) patients. There were 3 cases of 1+ in HER-2, 1 case of 2+ and no case of 3+. The case of HER-2 immunohistochemistry 2+ was tesed for HER-2 FISH and there was no HER-2 gene amplification. 6 cases (22.2%) had a low Ki- 67 index (<14%), and 21 cases (77.8%) had a proliferation index ≥ 14% (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The tumor demonstrates positive expression of chromogranin A (magnification × 100) B. CD56 is positively expressed in the membrane of tumor cells (magnification × 100) C. The tumor cells show strong expression of synaptophysin (magnification × 100) D. INSM1 is positively expressed in the nucleus of the tumor cells (magnification × 100).

11 cases (40.7%) were well-differentiated NETs and 16 cases (59.3%) were poorly differentiated NEC. In NETs the positive rate of ER was 10/11 (90.9%), while in NEC the positive rate of ER was 9/16 (56.3%). On the basis of immunophenotypes, most of NENBs were of the luminal molecular subtype, 6 cases were luminal A and 15 cases were luminal B, 6 cases were TNBC and had no HER-2 overexpression subtypes.

Treatment modalities

Currently there is no standard therapy for NENB; most treatments are similar to the treatment of invasive carcinomas, No Special Type (NST). Surgery was the first-line therapy, followed by chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. In our group all patients received surgical treatment. The most common surgical procedure was Modified Radical Mastectomy (MRM), which was performed in 21 patients, 4 cases received simple resection and sentinel lymph node biopsy. 2 cases underwent puncture diagnosis and neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical mastectomy. All cases had received chemotherapy, 14 cases had received radiotherapy and 19 cases with positive ER expression had received adjuvant hormonal therapy.

Outcome, recurrence and prognosis

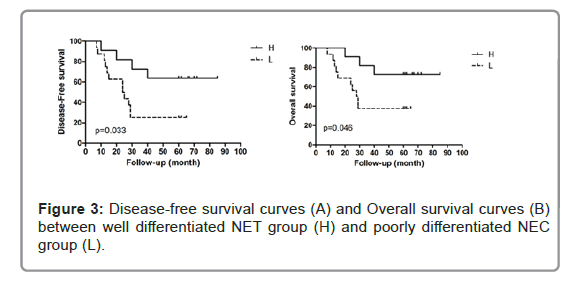

All patients were followed up until February 2020; the median follow-up time was 76 months (range, 39–87 months). In well differentiated NET group (H), 4 cases developed disease progression, of them one patient had local recurrence and survived long-term after treatment, 3 cases had distant metastasis (1, lung metastasis; 1, liver metastasis; and 1, multiple metastasis with lung, liver, brain). In poorly differentiated NEC group (L), 12 patients had disease progression, of them 4 patients had local recurrence: 2 cases survived long-term after treatment and 2 cases had progressed to distant metastasis after treatment. 8 patients had distant metastasis (1, lung metastasis; 2, liver metastasis; and 5, multiple metastasis with lung, liver, brain, bone). For 5-year DFS, the well differentiated NET group was 63.6% and poorly differentiated NEC group was 25%. There was a statistical difference between the two groups (P=0.033). For 5-year OS the well differentiated NET group (72.7%) was also significantly better than poorly differentiated NEC group (37.5%) (P=0.046) (Figure 3).

Discussion

Neuroendocrine differentiation in BC has been a matter of discussion since it was first described almost 60 years ago. Indeed NENB is a less well-defined group than analogous entity in other organ system, such as lung and gastroenteropancreatic tract. Various definitions and criteria on NENB have been used [6-8]. So the reported frequency of NENB and BC with neuroendocrine differentiation ranges from approximately 0.3%-30%.

In 2019, The 5th Edition WHO updated neuroendocrine neoplasms of breast again. Key change was classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms into NET and NEC and exclusion of special histologic types (solid papillary carcinoma and hyper cellular variant of mucinous carcinoma) and the inclusion of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. The 5th edition classification was based on an expert consensus from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and WHO, whose aim was to adapt a “common classification framework” to standardize the categorization of neuroendocrine tumors across all anatomic sites [9].

Neuroendocrine expression is common in invasive breast carcinoma NST. With typical morphological characteristics and expression of neuroendocrine markers can the BC be classified as NENBS? The 5th Edition WHO recommends classifying invasive carcinomas with <10% neuroendocrine morphology as invasive carcinoma NST and those with >90% as NET or NEC.

Our cohort strictly followed 2019 WHO criteria and each case was reviewed by two senior pathologists. NET diagnosis was referred to neoplasms with typical solid nests or trabeculae of spindle or polygonal cells, separated by fbrovascular stroma. NEC was composed either of small cells with extensive necrosis, uniform small hyperchromatic cells with high nuclear or cytoplasm ratio or large cells with evident cytoplasm and highly pleomorphic nuclei, morphologically resembling pulmonary high-grade NEC. Atleast one extensive positivity of NE marker was required to confirm the morphological diagnosis. In our actual case selection process, we found that the classification standard was not very clear in some respect, especially for highly differentiated NETs. The grading system used for NENB was the Nottingham system and not the proliferative grade proposed for GEP and pulmonary NETs (neither with Ki67 proliferative index nor with mitotic index). At this point, breast NET cannot fit well with gastrointestinal NET.

Immunohistochemical markers most commonly used to demonstrate neuroendocrine expression include Syn, CgA and CD56. Syn and CgA are specific markers, while CD56 is sensitive and less specific. A novel marker called Insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1) has been identifed in insulinoma tissue [10] and subsequently detected in different NE human cells and tumors. INSM1 is strongly expressed in most NETs with a specifc nuclear staining [11]. In our group, INSM1 was positively expressed in 23 of the 27 cases; both sensitivity and specificity are relatively strong. Practice proved that the combination of INSM1 is an effective supplement and improvement for the traditional neuroendocrine markers.

90.9% (10/11) NETs show positive expression of Estrogen Receptor (ER) with variable rates of Progesterone Receptor (PR) and 56.3% (9/16) NEC show ER expression. All the cases are typically HER2- negative. Ki-67 labeling index is high (>90%) in small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Molecular classification is the basis for breast cancer clinical treatment. In our cohort, most of NENBs were of the luminal molecular subtype, In 11 NETs, 6 cases were luminal A and 5 cases were luminal B, In 16 NECs, 10 cases were luminal B and 6 cases were TNBC and had no HER-2 overexpression subtype.

Research has shown that NENB is genetically heterogeneous and harbor molecular alterations that differ from invasive carcinoma NST [12]. Targeted sequencing analysis of NENBs revealed FOXA1, TBX3, GATA3, and ARID1A as the most frequently mutated genes [13]. Well differentiated NET of breast harbor a lower frequency of mutation affecting TP53 and PIK3CA as well as an enrichment of mutation affecting the transcription factors TBX3 and FOXA1 [14]. They show a low frequency of concurrent 1q gains and 16q losses [15,16]. Poorly differentiated NEC harbor recurrent co-occurring genetic alteration affecting TP53 and RB1 [17]. Alterations affecting genes of the PI3K signaling pathway including PTEN inactivating genetic alterations and PIK3CA mutation have been reported in breast small cell carcinomas [18,19]. A lot of evidence shows neuroendocrine breast tumors display similarities with neuroendocrine tumors arising in different anatomic locations [20]. The genetic differences observed between breast NETs and NECs suggest that these entities might not be part of the same spectrum, but rather that they might arise through different molecular mechanisms [21].

The most important differential diagnosis for neuroendocrine tumors in breast is metastatic tumor. There is considerable morphologic overlap between primary breast neuroendocrine tumors and those from other sites. We should have detailed medical history and comprehensive clinical information in our diagnosis and choose a series of immunohistochemical antibodies to help diagnosis and differential diagnosis. The positive expression of ER, PR, mamaglobin, GCDFP-15 and GATA3 and lack of expression specific to other sites of origin such as CDX2 and TTF-1 support primary breast NENB. We must remind us that neuroendocrine morphology and immunophenotype in the absence of ER expression and of in situ or invasive non-neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast should drive the attention to the possibility of a metastasis and prompt the search for the primary site.

There is no standard therapy for NENB yet. In practical work, molecular typing, clinical staging and histological grading remain the main prognostic factors for NENB. Most treatments of NENB are similar to the treatment of invasive carcinoma NST, with surgery as the first-line therapy, followed by chemotherapy and endocrine therapy [22]. From our data, it can be seen that the prognosis of poorly differentiated NEC was worse than that of well differentiated NET. In terms of both overall and disease-free survival, the poorly differentiated neuroendocrine nature of the neoplasm is an independent prognostic factor. As for advanced disease, some cases have been treated with platinum and etoposide-based regimens, in analogy with lung NEC, whereas in others a taxanes and anthracycline-based chemotherapy therapy has been attempted, but no consensus on a standard treatment has been reached, due to the small number of cases [23].

Conclusion

Considering the low frequency of NENB, there is limited knowledge on the clinical presentation and management of this neoplasm. Further understanding of the molecular mechanism of breast neuroendocrine neoplasms will aid in the treatment and prognostication of these tumors.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Authors Contributions

XJ and YZ contributed to the study conception and design. YZ and QZ contributed to the material preparation and analysis. Collection and assembly of data were performed by SF, WN and LZ. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by JZ and WD. Manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript were performed by all authors.

Funding

This study was supported by Key Projects of the Department of Education of Anhui Province (No. KJ2020A0593), the Natural Science Foundation of Bengbu Medical College (No. BYKY2019049ZD) and Anhui Province University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program Project (bydc2021001).

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All tissue samples were obtained with patients writing extensively informed consent when they were in hospital and the study was approved by the Bengbu Medical College ethical committee and conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (No.BBMEC-2021088).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Uccella S, Finzi G, Sessa F, La Rosa S (2020) On the Endless Dilemma of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Breast:a Journey Through Concepts and Entities. Endocr Pathol 31: 321–329.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pareja F, D'Alfonso TM (2020) Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the breast: A review focused on the updated World Health Organization (WHO) 5th Edition morphologic classification. Breast J 26:1160-1167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Talu CK, Leblebici C, Ozturk TK, Hacihasanoglu E, Koca SB,Gucin Z (2018) Primary breast carcinomas with neuroendocrine features: clinicopathological features and analysis of tumor growth patterns in 36 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 34:122-130.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thürlimann B, et al. (2011) Strategies for subtypes-dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer. Ann Oncol 22:1736–1747.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolf AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, Harvey BE, Mangu PB, et al. (2018) Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Testing in Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. J Clin Oncol 36:2105–2122.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bogina G, Munari E, Brunelli M, Bortesi L, Marconi M, et al. (2016) Neuroendocrine differentiation in breast carcinoma: clinicopathological features and outcome. Histopathology 68:422-432.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCullar B, Pandey M, Yaghmour G, Hare F, Patel K, et al. (2016) Genomic landscape of small cell carcinoma of the breast contrasted to small cell carcinoma of the lung. Breast Cancer Res Treat 158:195-202.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Natrajan R, Lambros MB, Geyer FC, Marchio C, Tan DS, et al. Loss of 16q in high grade breast cancer is associated with estrogen receptor status: evidence for progression in tumors with a luminal phenotype? Gene chromosome canc 48:351-365.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marchio C, Geyer FC, Ng CK, Piscuoglio S, FilippoMR , et al. (2017) The genetic landscape of breast carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. J Pathol 241:405-419.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kriegsmann K, Zgorzelski C, Kazdal D, Cremer M , Muley T, et al. (2020) Insulinoma-associated Protein 1 (INSM1) in thoracic tumors is less sensitive but more specifc compared with synaptophysin, Chromogranin A, and CD56. AppL Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 28:237–242.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seijnhaeve E, Galant C, Van Bockstal MR (2021) Nuclear Insulinoma-Associated Protein 1 Expression as a Marker of Neuroendocrine Diferentiation in Neoplasms of the Breast. Int J Surg Pathol 29:496-502.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lavigne M, Menet E, Tille JC, Lae M, Fuhrmann L, et al. (2018) Comprehensive clinical and molecular analyses of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast. Mod Pathol 31:68-82.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon SY, Bae YK, Gu MJ, Choi JE, Kang SH, et al. (2014) Neuroendocrine differentiation correlates with hormone receptor expression and decreased survival in patients with invasive breast carcinoma. Histopathology 64:647-659.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalinsky K, Jacks LM, Heguy A, Patil S, Drobnjak M, et al. (2009) PIK3CA mutation associates with improved outcome in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15:5049–5059.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inno A, Bogina G, Turazza M, Bortesi L, Duranti S, Massocco A (2016) Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: current evidence and future perspectives. Oncologist 21:28-32.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cloyd JM, Yang RL, Allison KH, Norton JA, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. (2014). Impact of histological subtype on long-term outcomes of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 148:637–644.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shin SJ, DeLellis RA, Ying L, Rosen PP (2000) Small cell carcinoma of the breast: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of nine patients. Am J Surg Pathol 24:1231-1238.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoon YS, Kim SY, Lee JH, Kim SY, Han SW (2014) Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: radiologic and pathologic correlation. Clin Imaging 38:734–738.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rigi L, Sapino A, Marchio C, Papotti M, Bussolati G (2010) Neuroendocrine differentiation in breast cancer: established facts and unresolved problems. Semin Diagn Pathol 27: 69–76.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, et al. (2012) The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 486:346–352.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490: 61–70.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohanty SK, Kim SA, DeLair DF, Bose S, Laury AR, et al. (2016) Comparison of metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms to the breast and primary invasive mammary carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. Mod Pathol 29:788- 798.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosen LE, Gattuso P (2017) Neuroendocrine tumors of the breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med 141:1577-1581.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Zhao Y, Zhu Q, Fan S, Nan W, Zhu J, et al. (2022) Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of Breast: A Rare Breast Tumor Worthy of Attention. Diagnos Pathol Open 7:199. DOI: 10.4172/2476-2024.1000199

Copyright: © 2022 Zhao Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2329

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Apr 03, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1810

- PDF downloads: 519