Research Article Open Access

Mortality at a Portuguese Internal Medicine Service: Is Patient Allocation a Determinant Factor?

Luciana Sousa*, Ana Rita Marques, Inês Burmester, Isabel Apolinári and Ilídio BrandãoInternal Medical Residents at Internal Medical Service, Hospital de Braga, Portugal

- *Corresponding Author:

- Luciana Sousa

Internal Medical Residents at Internal Medical Service

Hospital de Braga, Portugal

Tel: +351 253 027 000

E-mail: lucianaalsousa@hotmail.com

Received date: April 24, 2017; Accepted date: May 24, 2017; Published date: May 29, 2017

Citation: Sousa L, Marques AR, Burmester I, Apolinári I, Brandão I (2017) Mortality at a Portuguese Internal Medicine Service: Is Patient Allocation a Determinant Factor? J Palliat Care Med 7:306. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000306

Copyright: © 2017 Sousa L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Objectives: To verify if patient’s allocation by different wards is a determinant factor of mortality risk.

Design: Retrospective longitudinal study, using individual patient data from Internal Medicine Service in Hospital de Braga, Portugal.

Setting: From 1st to 31th January 2015.

Participants were eligible to our study all patients admitted do Internal Medical care, who hadn’t been transferred from different specialty’s wards during hospitalization or remained at Intermediate Care Unit in Emergency Room more than 24 hours.

Main outcome measures: Patients admitted to Internal Medicine’s wards and those admitted on other specialty’s wards, were compared for all-cause mortality, 2nd day mortality means and time to death. Analyses using t-student test and χ2 test (SPSS Statistics 22.0).

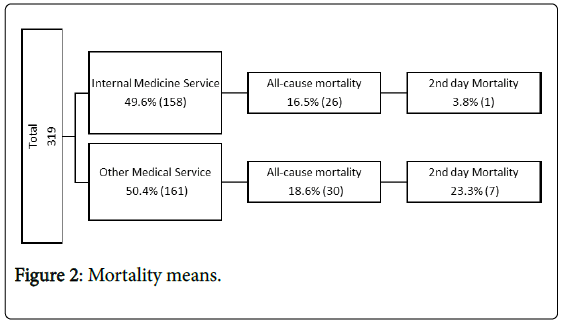

Results: A total of 319 patients were included in our study, 49.5% (158) were admitted to our medical wards and 50.5% (161) were admitted to a different specialty ward. There were respectively 16.5% (26) and 18.6% (30) total deaths and 3.8% (1) and 23.3% (7) 2nd day mortality. We also find that Internal Medicine ward time to death was 12.0 days and other inpatient ward time to death was 6.13 days. There was no statistically significant difference between groups for all-cause mortality (t(317)=-0.510; p=0.611; d=0.07), but for 2nd day mortality and time to death we found a statistic significant difference (t(44)=2.11; p=0.04; d=-0.56) and (t(37.2)=3.32; p-value=0.002; d=0.92) respectively.

Conclusions: The present study highlight “patient allocation” as a determinant factor for early mortality risk. Further research is needed to understand which morbidity and mortality factors are associated with these findings.

Keywords

Patient's allocation; Mortality; Internal medicine

Introduction

In recent years, hospitalized patient’s complexity has progressively increased, contributing to increase in healthcare surveillance need and nursing. Despite the problem’s size, few studies have been dedicated to determine mortality predictors among hospitalized patients [1].

A previous study had identified Portugal as the southern-western Europe country with the most higher rate of excess winter mortality due to socioeconomic reasons, which could be reduced in part by increased public spending on health care [2]. In our service, during winter period, the number of patients requiring hospital admission exceeds the number of available beds so patients are often placed on other specialty wards.

Evidence support that the most significant factors associated with mortality risk are functional level of dependence, previously institutionalization, admission’s diagnosis, advanced age, masculine sex and dementia [3], other studies outline that there’s a peak mortality risk at 2nd day in-hospital stay [4,5], and that there is a difference in mortality of patients admitted during week compared to those admitted at the weekend, difference in which is thought to be related with reduction of staff members [6-16]. Likewise, the fact that a patient in need of medical care, has been admitted in to a different specialty ward, could mean that the quality of patient care may be compromised and therefore the risk of death increased.

If this hypothesis is confirmed, this could mean that hospital organization should be rethought. In the literature, little is said about hospital allocation as a predictor factor for mortality. Taking this in to account, we hypothesized that patient allocation could be a determinant mortality risk factor.

Methods

Data collection

We identified, using data collected from clinical charts, every patient admitted to Internal Medicine care, from emergency department, between January 1st to January 31st, 2015. This period was chosen based on the large number of patients observed, corresponding to approximately twice the Internal Medicine Service’s bed capacity.

Patients transferred from other specialty wards to Internal Medicine Service ward during hospitalization or patients that remained at Intermediate Care Unit in Emergency Room more than 24 hours, were excluded from the study. We identified every patient who had died in this period of time and then our sample was divided in two groups: patients allocated in to Internal Medicine Service (4C, 4D, 4E) and those in the remainder services.

Variables definitions

We considered a patient to be independent if he didn’t need help from a third person on daily basic activities, such as diet, hygiene and mobility; patients in need of support in one of these activities were considered to be partially dependent and if they needed help at least in two of these activities were considered to be dependent in daily basic activities.

Secondary diagnoses included comorbidities and all diagnoses made at admission and during hospitalization.

Admission’s diagnoses were divided in five groups: cardiovascular, respiratory, genitourinary, gastrointestinal and oncologic based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD)–10th edition.

A Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [17,18] was used to access mortality risk at admission. This is a weighted index based on a mathematical model that takes into account the number and the severity of comorbid diseases, a valid method to estimate death’s risk from co-morbid disease in medical patient [19].

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis we used demographic variables (age and sex); variables considered in other studies as predictors factors for mortality in hospitalized patients (dependence level, admission diagnosis, number of comorbidities/secondary diagnosis, number of admissions in previous year) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

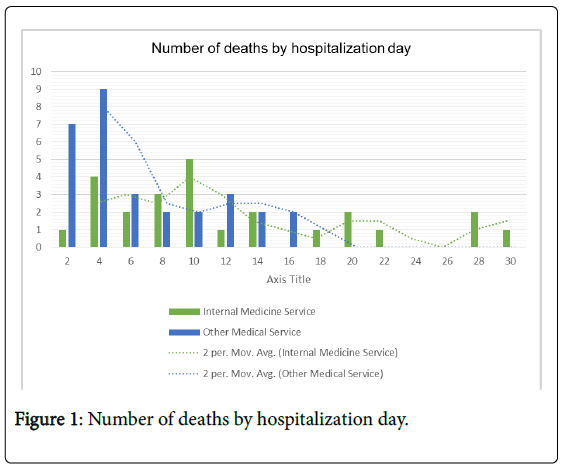

Sample characteristics were described by means, standard deviation, frequencies and percentages. Mortality means were compared for inpatient’s death at second day of hospitalization and during total stay. We used a t-student test for independent samples to compare mortality means between the two groups, we also compare groups for time to death (number of hospitalization days until death), using SPSS Statistics 22.0. (Figure 1) Potential confounding factors (previously described) were also compared using a t-student test and a chi-square test. For significance level we used a p-value (p<0.05) and effect size tests (Figure 2).

Results

Hospital setting

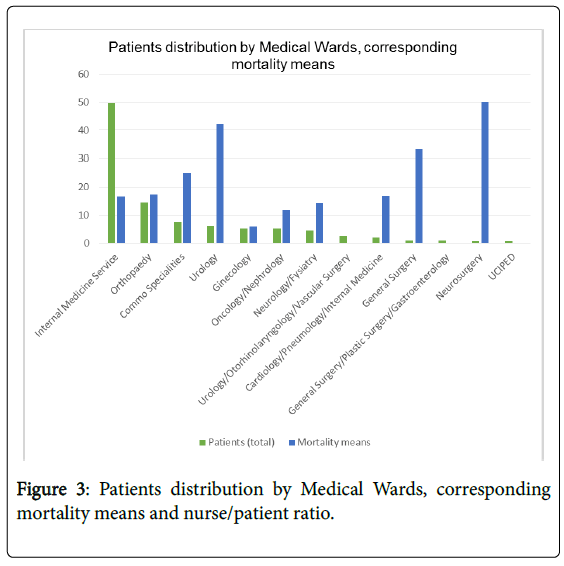

Hospital de Braga’s Internal Medicine Service is located on the 4th floor, lying over 3 wards (4C, 4D and 4E), each of which has 30 beds, divided into 17 double rooms and 4 individual rooms. There are also five beds available in another ward (ward 4B) that is shared with Cardiology and Pneumology (in this study this ward was considered "other service" because nursing care isn’t differentiated by specialty). Other service wards have the same logistics. In January patients hospitalized in to Internal Medical care were allocated on the following services: Internal Medicine Service (4C, 4D, 4E) 49.6% (158) patients; Cardiology/Pneumology/Internal Medicine (4B) 1.88% (6) patients; Oncology/Nephrology (1C) 5.33% (17) patients; Neurosurgery (1D) 0.63% (2) patients; General Surgery (2B) 0.94% (3) patients; General Surgery/Plastic Surgery/Gastroenterology (2C) 0.94% (3) patients; Urology/Otorhinolaryngology/Vascular Surgery (2D) 2.51% (8) patients; Urology (2E) 5.96% (19) patients; Orthopedics (3B, 3C and 3D) 14.4% (46) patients; Neurology/Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (3E) 4.39% (14) patients; Gynecology (5D) 5.33% (17) patients and "Common Services" (1E and former Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit) 7.52% (24) and 0.63%(2) patients respectably. For each ward, nurse/patient ratio varied from 1/7 to 1/12. Patients distribution by service, corresponding mortality means and the nurse/ patient ratio are described in the (Figure 3 and Table 1).

| Service | Patients (Total) % (Nº) | Patients (Death) % (Nº) | Nurse/Patient Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal medicine service wards | Internal Medicine (4C, 4D, 4E) | 49.6 (158) | 16.5 (26) | 01/11 |

| Other medical service wards | Oncology/Nephrology (1C) | 5.33 (17) | 11.8 (2) | 01/09 |

| Neurosurgery (1D) | 0.63 (2) | 50.0 (1) | 01/09 | |

| General Surgery (2B) | 0.94 (3) | 33.3 (1) | 01/11 | |

| General Surgery/Plastic Surgery/ Gastroenterology (2C) | 0.94 (3) | 0.00 (0) | 01/11 | |

| Urology/ Otorhinolaryngology/ Vascular Surgery (2D) | 2.51 (8) | 0.00 (0) | 01/12 | |

| Urology (2E) | 5.96 (19) | 42.1 (8) | 01/12 | |

| Orthopaedy (3B, 3C, 3D) | 14.4 (46) | 17.4 (8) | 01/11 | |

| Neurology/ Fhysiatry (3E) | 4.39 (14) | 14.3 (2) | 01/10 | |

| Cardiology/ Pneumology /Internal Medicine (4B) | 1.88 (6) | 16.7 (1) | 01/10 | |

| Ginecology (5D) | 5.33 (17) | 5.88 (1) | 01/10 | |

| Common Specialties (1E) | 7.52 (24) | 25.0 (6) | Variable | |

| Former Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit (UCIPED) | 0.63 (2) | 0.00 (0) | Variable | |

| Total | 100 (319) | 100 (56) | ||

Table 1: Patients distribution by Medical Wards, corresponding mortality means and nurse/patient ratio.

Sample description

From 1st to 31th January Internal Medicine observed more than seventeen hundred people, three hundred and nineteen were included in our study and fifty-six had died. From a total of 319 patients included in our study, 49.5% (158) were admitted to our medical wards and 50.5% (161) were admitted on a different specialty ward. There were respectively 16.5% (26) and 18.6% (30) total deaths and 3.85% (1) and 23.3% (7) 2nd day mortality (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Medical Service | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine (N = 26) | Other Service (N = 30) | |||||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Mean | Std. Deviation | p-value | Effect size | |

| Age | 84.8 | 7.27 | 82.6 | 12.5 | 0.425 | 0.22 |

| Sex (female) | 62 | 0.5 | 53 | 0.51 | 0.536 | -0.08 |

| Dependence Level | ||||||

| Independent | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.34 |

| Partial dependent | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.8 | 0.06 |

| Dependent | 0.7 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.5 | 0.37 | 0.27 |

| Secondary diagnosis | 6.01 | 1.96 | 6.67 | 3.03 | 0.39 | 0.23 |

| Admissions in the last year | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.18 | 0.36 |

| CC Risk index | 23.5 | 9.13 | 24.4 | 10.1 | 0.74 | 0.09 |

| Admission’s diagnoses | ||||||

| Respiratory | 0.61 | 0.5 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.16 |

| Cardiovascular | 0.19 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 0.14 |

| Oncologic | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.17 |

| Genitourinary | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.2 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| Gastrointestinal | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 | 0.16 | # |

| All-cause mortality | 16 | 0.37 | 19 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.07 |

| 2nd day Mortality | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 0.004 | -0.56 |

| Time to death | 12 | 8.11 | 6.13 | 4.39 | 0.002 | 0.92 |

Table 2: Sample characteristics.

In the analysis of the 56 people who had died, we observed that, 42.9% (24) were men and had a mean age of 83.6 years old. Internal Medicine ward time to death (number of hospitalization days until death) was 8.88 days (12.0 days for patients allocated in Internal medicine service wards (4C,4D, 4E) and 6.13 days for those in others medical wards). The main reasons for hospitalization were: respiratory disease 58.9% (33); cardiovascular disease 23.2% (13); genitourinary 8.9% (5); oncologic 5.36% (3); gastrointestinal 3.6% (2). On average, patients had 6.4 secondary diagnoses; 41.1% (23) of patients were dependent on daily life activities, 8.93% (5) were partially dependent, 19.6% (11) were independent and 50.0% (28) had at least one hospitalization in the last year.

Samples homogeneity

Previously described factors were also analyzed: age (t(54)=0.80; p=0.425; d=0.20); sex (χ2(1)=0.38; p=0.536; Phi=-0.083); admission’s diagnosis (respiratory (t(52)=0.582; p=0.563; d=0.16); cardiovascular (t(52)=-0.50; p=0.61; d=0.14); genitourinary (t(42.6)=-1.35; p=0.185, d=0.34); oncologic (t(52)=0.65; p=0.52, d=0.17); (gastrointestinal (t(25)=1.44; p=0.16)) dependence level (independent (t(49)=-1.22; p=0.23; d=0.34; partially dependent (t(49)=0.25; p=0.80; d=0.06); dependent (t=(48.2)=0.91; p=0.37; d=0.27)), number of secondary diagnosis (t(50.2)=-0.09; p=0.386; d=0.23); Charlson comorbidity index (t(54)=-0.331; p=0.742; d=0.09) and number of admissions in the previous year (t(54)=-1.35; p=01.82; d=0.36).

Risk mortality factors analysis

There was no statistically significant difference between groups for all-cause mortality: (t(317)=-0.510; p=0.611; d=0.07) but for “2nd day mortality” (t(44)=2,11; p=0,04; d=-0,56) and for “time to death” (t(37.2)=3.318; p-value=0.002; d=0.92), we found a statistic significant difference. If patients were at an Internal Medicine service, they survived for an average of 12.0 days and if they were allocated to another inpatient ward survived for an average of 6.13 days.

Discussion

As expected, the number of patients observed exceeded in more than 50% the number of Internal Medicine Service’s available beds. Like in other studies, our patients had advanced age, the majority had several comorbidities and were dependents in daily activities. They were hospitalized mostly for a respiratory disease and had at least one prior hospital admission in the last year [3,17,18].

Hospital’s mortality monitoring helps to assess and improve quality of care. Several studies have determined the biological/pathological factors associated with increased risk of death in hospitalized patients, but little is the existing evidence regarding the factors associated with quality health care and its contribution to mortality risk. This study has shown that “patient allocation” could be a determinant factor for early mortality risk. We demonstrate that there was a significant difference in 2nd day mortality. Patients admitted to other medical ward, seem to die sooner that those admitted to Internal Medicine service ward but, contrary to what it might seem from our clinical experience, this study showed no significant differences in mortality means.

Authors are unaware of the associated factors, but suggests that these differences could result from differences in levels of service staffing (and consequently a minor capacity for patient’s monitoring in those with a smaller nurse/patient ratio) and physical barriers to medical attention (since Internal Medicine doctors spent most of their time in their service ward).

Strength and limitations of this study

We used a comparative design that demonstrated significant differences even with a small sample and effect size analysis shown that the variable implicated had impact as mortality factors.

The two groups analyzed were similar for variables described in previously studies as factors associated with increased mortality risk, so results were not influenced by age, sex, dependence level, admission diagnosis, number of comorbidities/secondary diagnosis, number of admissions in previous year and Charlson Comorbidity Index, but other factors like week/weekend were not included.

This study is a retrospective analysis; some information may have been lost. The period of time analyzed and sample size were small and was based on data from only one Medical Service care, in which organizational structure may be different from other hospitals in other regions and countries.

The number of patients distributed by medical wards did not allow to analyzed significant differences between mortality means.

Despite of are limitations, this paper can be a pilot study contributing for future prospective research studies.

Conclusions

The present study highlight “patient allocation” as a determinant variable for early mortality risk but further studies are needed to identify which morbidity and mortality factors are associated with it.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrício Costa and Mónica Gonçalves, from the Clinical Academic Center – Braga (2CA-Braga) for the support and enthusiasm for the project.

References

- Silva TJ, Jerussalmy CS, Farfel JM, Curiati JA, Jacob-Filho W (2009) Predictors of in-hospital mortality among older patients. CLINICS 64: 613-618.

- Healy JD (2003) Excess winter mortality in Europe: a cross country analysis identifying key risk factors. J Epidemiol Community Health 57: 784-789.

- Sousa S, Moraes M, Blessed V, Corredoura AS, Rodrigues G, et al. (2002) Increased mortality. Factors predictive of morbidity and hospital mortality and six months in hospitalized elderly patients. Acta med Portug 15: 177-184.

- Bell CM, Redelmeier DA (2001) Mortality among patients to hospitals on weekends admitted as compared with weekdays. N England J Med 345: 663-668.

- Tribuna C, Apolinário I, Angela C, Carvalho A, Gonçalves FN. Association between death and the admission in internal medicine to end-of-week. 17th National Congress of Internal Medicine.

- Mohammed MA, Sidhu KS, Rudge G, Stevens AJ (2012) Weekend admission to hospital has a higher risk of death in the elective setting than in the emergency setting: a retrospective database study of national health service hospitals in England. Mohammed et al. BMC Health Serv Res 12: 87.

- Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE (2004) Effects of Weekend Admission and Hospital Teaching Status on In-hospital Mortality. AMJ Med 117: 151-157.

- Barba R, Losa JE, Velasco M, Guijarro C, Garcia dC, et al. (2006) Mortality among adult patients admitted to the hospital on weekends. Eur J Intern Med 17: 322-324.

- Gogel HK. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1500-1501.

- Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, Shao YH, Wilson AC, et al. (2007) Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 356: 1099-1109.

- Peberdy MA, Ornato JP, Larkin GL, Braithwaite RS, Kashner TM, et al. (2008) Survival from inhospital cardiac arrest during nights and weekends. JAMA 299: 785-792.

- Redelmeier DA, Bell CM (2007) Weekend worriers. N Engl J Med 356:1164-1165.

- Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, Bayer N, Hachinski V (2007) Weekends: a dangerous time for having a stroke? Stroke 38: 1211-1215.

- Schmulewitz L, Proudfoot A, Bell D (2005) The impact of weekends on outcomes for emergency patients. Clin Med 5: 621-625.

- Hasegawa Y, Yoneda Y, Okuda S, Hamada R, Toyota A, et al. (2005) The effect of weekends and holidays on stroke outcome in acute stroke units Cerebrovasc Dis 20: 325-331.

- Becker DJ (2007) Do hospitals provide lower quality care on weekends? Health Serv Res 42: 1589-1612.

- Briongos-Figuero LS, Hernanz-Román L, Pineda-Alonso M, Vega-Tejedor G, Gómez-Traveso T, et al. (2015) In-hospital mortality due to infectious disease in an Internal Medicine Department. Epidemiology and risk factos. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 19: 567-572.

- BieŇ? B, BieŇ?-Barkowska K, Wojskowicz A, Kasiukiewicz A, Wojszel ZB (2015) Prognostic factors of long-term survival in geriatric inpatients. Should we change the recommendations for the oldest people? J Nutr Health Aging 19: 481-488.

- Tal S, Guller V, Shavit Y, Stern F, Malnick S (2011) Mortality predictors in hospitalized elderly patients. Q J Med 104: 933-938.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2740

- [From(publication date):

May-2017 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 1932

- PDF downloads : 808