Modulations of Mammalian Brain Functions by Antidepressant Drugs: Role of Some Phytochemicals as Prospective Antidepressants

Received: 04-Dec-2015 / Accepted Date: 27-Jan-2016 / Published Date: 02-Feb-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2471-9919.1000103

Abstract

Depression in the form of serious mental illness is known to influence overall physiological and cognitive functions of any individual. Existing reports suggest that many brain regions mediate the diverse symptoms of depression but exact root cause of this illness is not yet known. However, several biochemicals, molecular and genetic bases have been found to be associated with brain disorders leading to depression. People with depression can best be treated with medications, psychotherapies, and other viable methods. The most commonly used antidepressants are the serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-nor-epinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs), buprenorphine and nor-adrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSAs) but most of them possess serious side effects in patients. The present review article illustrates an updated account of our understanding about the molecular constituents of the different regions of the brain that control the physiological and behavioural functions of a person, mechanisms of actions of currently available antidepressants and their side effects, if any, as well as the prospects of using phytochemicals as safe and effective alternative medicines.

Keywords: Depression; Brain functions; Antidepressant drugs; Antipsychotic plants; Herbal ingredients; Prospective antidepressants; Psychotherapies

41697Introduction

Depression is the most common form of mental illness. It is a state of low mood that can affect a person’s thoughts, feelings, behavior and senses of a well-being, disturbed sleep, typically with early morning awakenings, leading to decrease in sleep duration and seasonal affective disorder [1-4]. The cause of depression could be Adversity in childhood, such as bereavement, unequal parental treatment of siblings, neglect, sexual abuse, life events include job problems, financial difficulties, a medical diagnosis, bullying, relationship troubles, separation, natural disasters, catastrophic injury, social isolation, jealousy, loss of a loved one, childbirth, and menopause [5-9] and resulting changes significantly increases the depression. Adolescents may be more prone to experiencing depressed mood [10]. The symptoms of depression which are observed today were recognized in ancient times. The ancients were also recognized a large overlap of depression with anxiety and excessive alcohol consumption, both of which are well established today. It is likely that many brain regions mediate the diverse symptoms of depression. While many brain regions have been implicated in regulating emotions, we still have a very rudimentary understanding of the neural circuitry underlying normal mood and the abnormalities in mood that are the hallmark of depression. This lack of knowledge is underscored by the fact that even if it were possible to biopsy the brains of patients with depression, there is no consensus in the field as to the site of the pathology and hence the best brain region to biopsy. However, studies of the brains of depressed patients obtained at autopsy have reported abnormalities in many of these same brain regions. Knowledge of the function of these brain regions under normal conditions suggests the aspects of depression to which they may contribute. Given the prominence of so-called neurovegetative symptoms of depression, including too much or too little sleep, appetite, and energy, as well as a loss of interest in sex and other pleasurable activities, a role for the hypothalamus has also been speculated.

On the basis of severity of depression, it can have several forms: Major depression is characterized by appearance of severe symptoms that interfere with your ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy life. Persistent depressive disorder occurs in a person diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder may have episodes of major depression along with periods of less severe symptoms, but symptoms must last for 2 years. Psychotic depression occurs in a person who has severe depression plus some form of psychosis, such as having disturbing false beliefs or a break with reality, or hearing or seeing upsetting things that others cannot hear or see. Postpartum depression is much more serious than the "baby blues" that many women experience after giving birth, when hormonal and physical changes and the new responsibility of caring for a new-born can be overwhelming. It is estimated that 10 to 15 per cent of women experience postpartum depression after giving birth. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is characterized by the onset of depression during the winter months, when there is less natural sunlight. The depression generally lifts during spring and summer. SAD may be effectively treated with light therapy, but nearly half of those with SAD do not get better with light therapy alone. Antidepressant medication and psychotherapy can reduce SAD symptoms, either alone or in combination with light therapy. Bipolar disorder is also called as manic-depressive illness. It is characterized by cycling mood changes from extreme highs (e.g., mania) to extreme lows (e.g., depression).

Many women face the additional stresses of work, home responsibilities, caring for children, aging parents, abuse, poverty, and relationship strains. Women's higher depression rate may be linked to biological life cycle, psychosocial, and hormonal factors that a women experience. Women may also have a severe form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) called premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). During the transition into menopause, women experience an increased risk for depression in addition with that; osteoporosis may also be associated with depression.

Men are more likely to be very tired, irritable, lose interest in oncepleasurable activities, frustrated when discouraged, irritable, angry, and sometimes abusive and have difficulty in sleeping. When men are depressed they may more likely turn to alcohol or drugs. Some men throw themselves into their work to avoid talking about their depression with family or friends, or behave recklessly.

When older adults do have depression, it may be overlooked. They may be less likely to experience feelings of sadness. Older adults may also have more medical conditions such as heart disease, stroke, or cancer, which may cause depressive symptoms. They may be taking medications with side effects that contribute to depression. Some older adults may experience vascular depression, or sub-cortical ischemic depression also called arteriosclerotic depression. Those with vascular depression may have risk for, co-existing heart disease. Older adults with depression improve when they receive treatment with an antidepressant, psychotherapy, or a combination of both.

Children who develop depression often have episodes. Childhood depression often persists, recurs, and continues into adulthood, if left untreated. Depression during the teen years comes at a time of great personal change a when boy or a girl is forming an identity apart from their parents and emerging sexuality for the first time in their lives. Before puberty, boys and girls are equally developing depression. However, girls are twice as likely as boys to have had a major depressive episode. A child with depression may pretend to be sick, refuse to go to school, cling to a parent, or worry that a parent may die. Older children may get into trouble at school, be negative and irritable, and feel misunderstood. It can also lead to increased risk for suicide. It may be difficult to accurately diagnose a young person with depression, because the signs may be viewed as normal mood swings of children as they move through developmental stages.

Thus, we are interested in understanding the molecular constituents of the brain's reward regions that control the functioning of these circuits under normal conditions as well as the molecular changes that drugs and stress induce these circuits that contribute to symptoms of addiction and depression. People with depression can get better with treatment by medications, psychotherapies, and other methods can effectively treat people, even those with the most severe depression.

Scientific Bases Of Depression

Molecular and genetic bases of depression

Genes coding for neurotrophic factors and brain signaling molecules which play regulatory roles in many neuronal functions are, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5 - HT). These two factors are two different signaling molecules functioning in separate but overlapping pathways and play regulatory role in functions, like neuronal survival, neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity and regulation of depression.

BDNF and its receptors are a widely distributed neurotrophin found in the brain and were first isolated as a secretory protein [11,12]. Its gene has a complex structure with several isoforms [13,14]. The promoters of individual BDNF transcripts are regulated by various physiological factors [15-17]. BDNF function is mediated though the receptor systems, p75 neurotrophin (p75NTR) and tropomyosinreceptor kinase beta (Trkβ). These receptors are present on membrane of intracellular vesicles in the absence of signals and their presence enhances the specificity of Trkβ for the primary ligand, BDNF [18-23]. The level of cAMP, electrical activity, and Ca++ ion stimulate exocytosis of these cytoplasmic vesicles into the cell surface, releasing Trkβ on the outer membrane with other receptors [24,25]. After binding with BDNF Trkβ dimerizes and is autophosphorylated at several tyrosine residues [26]. Phosphorylation of tyrosine at position 490 in Trkβ activates phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PIK3) which through Akt1/2 increases transcription of Bcl - 2, and Bax which is responsible for neuronal survival. Phosphorylation of tyrosine at position 785 of Trkβ recruits phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1) [27] which hydrolyses phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, generating inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 promotes Ca++ release from endoplasmic reticulum and also activates protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca++-calmodulin regulated protein kinase. PKC is required for neurotrophic growth factor (NGF), to activate Erk1 and Erk2 [28]. Activation of Erk / MAPK-Ras signaling cascade is essential for neurotrophin-promoted differentiation of neurons [29,30].

Depression is characterized by two events: behavioral despair and the inability to experience pleasure. These behaviors are controlled by two interacting brain systems: the brain stress system by HPA pathway and the brain reward system via ventral tegmental area-nucleus accumbens (VTA - NAc) and VTA prefrontal cortex. VTA - Nac is the origin of dopaminergic neurons. The dopaminergic VTA-NAc pathway plays a crucial role in reward and motivation. The effects of BDNF on these two systems have been shown experimentally. The BDNF produces anti-depressive effects through hippocampal infusion [31,32]. It appears to play a prodepressive role in the VTA-NAc reward system [33]. Berton et al., has shown that mice with wild-type BDNF showed social withdrawal, while mice with BDNF gene deletion prevented social defeat, similar to the effect seen with chronic antidepressant treatment by repeated exposure to aggression. It has also been found that neural progenitor cells failed to produce antidepressant-induced proliferation and neurogenesis in mice lacking hippocampal Trkβ [34,35]. BDNF has been reported to regulate the transmission at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses by presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms [30,36]. The more detailed investigation on the effects of BDNF manipulations on behavior related to anhedonia and motivation, and despair and stress is needed.

5-HT/serotonin regulate a wide range of functions such as behavior, cognition and mood. There are 15 genes which have been reported for encoding 5-HT receptors in mammalian brain and all of them are G-protein coupled receptors, except ionotropic 5 - HT3 [37]. The 5 - HT is removed by 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter (5 - HTT) of the presynaptic neurons from synaptic cleft. It has been reported that the longer duration serotonin present in synaptic cleft longer the activation, which lead to depression [38]. 5-HTT is encoded by a single gene SLC6A4 and has a polymorphism (5 - HTTLPR) in 5-HTT promoter region [39]. This abnormal 5 - HTTLPR signaling has been shown to be associated with anxiety, depression and suicides [38,40-44]. It has been found that unipolar depression is associated with diminished serotonergic function that lead to warping in cognitive processing and emotions [45,46]. Studies in preschoolers have been reported a correlation between BDNF and 5 - HTTLPR polymorphisms in development of brain and shown high level of cortisol which may be a cause of depression [47]. However, studies in adolescents have been shown to be more involved in depression [46,48]. In India, studies in adults aged 40–50 years found that homozygous individuals with the short (s / s) variant showed a poor treatment response to the escitalopram [49]. Besides BDNF and 5 - HTTLPR, a few of the top prioritized gene products are presented below and several of them are listed in Table 1.

| Gene | Susceptible variants | location | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SerotonergicSLC6A4 | 14-16 repeats upstream to transcript initiation site | 17q11.2 | Serotonin transporter | [42,48] |

| HTR1 A | rs6295 rs878567 | 5q11.2-q13 | Serotonin receptor subfamily | [50-52] |

| HTR2A | rs6311 rs6313 | 13q14.2 | Serotonin receptor | [53,54] |

| TPH2 | rs4570625 | 12q21.1 | Rate limiting enzyme in serotonin biosynthesis | [55-57] |

| Dopaminergic DBH | rs6271 rs5320 | 9p34 | Enzyme converting dopamine to nor epinephrine | [58-60] |

| DRD2 | Rs6277 | 11q22-23 | Dopamine G-coupled receptor inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity | [61] |

| DRD4 | C616G C521T | 11p15.5 | Dopaminergic D4 receptor | [62] |

| Neurotrophin BDNF | rs6265 | 11p13 | Protein involved in brain development | [63,64] |

| NGFR | rs2072446 | 17q21-22 | Trk receptor | [65] |

| Other COMT | rs4680 | 22q11.21 | Enzyme degrading catecholamines | [66-68] |

| GNB3 | rs5443 | 12p13 | G-protein involved in signal transduction | [69-71] |

| DTNBP1 | rs760761 rs26019522 | 6p22.3 | Important for biosynthesis of lysozyme related organelles | [72-74] |

| MAO-A | rs1137070 | Xp11.3 | Mitochondrial enzyme catalyzing oxidative deamination of amines | [75] |

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | 1p36.3 | Folate and homocysteine Metabolim | [76-79] |

| GRIA3 | rs687577 | 3q11.9 | Neuronal development | [80] |

| APOE | Epsilon-4 | 19q13.2 | Associated with the late life depression including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases etc. | [81,82] |

| FKBP5 | rs9296158 | 12p13.33 | Protein folding and trafficking | [83-85] |

Table 1: Important variants of different genes involved in stress and depression.

FK506-binding proteins 5 (FKBP5) plays role of immunoregulation, protein folding, trafficking and interacts with HSP90, P23 and mature corticoid receptors such as progesterone, glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid receptors. SNPs of FKBP5 (rs9296158, rs3800373, rs1360780 and rs9470080) have been shown to be associated with childhood trauma [83]. It was also reported that this protein is associated with higher rate of depressive disorders [85,86]. An increased level of FKBP51 can be correlated with anxiety phenotype and therefore, efforts to discover a drug has been focusing on depleting FKBP51 levels, which may yield novel antidepressant therapies [87].

Biochemical basis of depression

Dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) catalyses a key step in biosynthesis of nor-adrenaline from dopamine. The low activity of DBH has been correlated [88,89] and may be considered as a biomarker of depression.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) plays an important role in modulating neuronal and immune interactions. The studies reported that proinflammatory cytokines (TNF - alpha) and interleukins (IL6 and IL10) were increased in patients with depression [90-92]. Receptors of IL, tachykinin receptors NK1 and NK2 expressed in monocytes are increased in major depression and may be considered as biomarkers.

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) plays an important role in mood stabilization, and is also involved in neural cell development and energy metabolism. GSK3β has been reported to be involved with depression [93,94].

Tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) is a rate-limiting enzyme of serotonin biosynthesis, which catalyses the conversion of tryptophan to 5 - hydroxytryptophan (5 - HTP). TPH2 has been shown to be associated with the several depressive disorders such as depressionassociated personality traits, anxiety, bipolar disorder, aggression, and suicide, deficits in cognitive control and emotion and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [95]. TPH2 variant (rs120074175) has been shown to be associated with the depression [96], but studies in further years failed to establish this association [97-99]. TPH1, an isoform of TPH2 expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and pineal gland [100], has been reported that rs2108977 of TPH1 is associated with hyperphagia, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), higher level of anxiety and depression.

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) degrade catecholamine, like dopamine, epinephrine and nor-epinephrine, therefore it is involved in the inactivation of catecholamine neurotransmitters. An SNP of COMT, rs4680 corresponds to Val108Met (soluble form) and Val158Met (membrane bound form) [101,102]. rs4680 has been reported to be associated with bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and Parkinson’s disease. These indices however could be exploited as suitable targets to develop effective antidepressants [67,103-106].

The mammalian brain has many specialized brain systems that work across specific regions under depression. Some of the most studied regions are listed in Table 2.

| Brain region | Normal function | How it is associated | Abnormal function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amygdala | brain’s fear hub which activates our natural fight-or-flight response | Amygdala helps create memories of fear and safety, may help to improve treatments for anxiety disorders like phobias or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). | ||

| Prefrontal cortex (PFC) | the brain's executive functions, such as judgment, decision making, and problem solving,PFC is involved in using short-term working memory and in retrieving long-term memories, also helps to control the amygdala during stress | |||

| Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) | controlling blood pressure and heart rate, sense a mistake, feel motivated, stay focused on a task, and managing emotions | Reduced ACC activity has been linked to disorders such as ADHD, schizophrenia, and depression. | ||

| Hippocampus | helps to create and file new memories | may be involved in mood disorders through its control of a major mood circuit called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis | When damaged it can't create new memories, but can still remember past events and learned skills, and carry on a conversation, all which rely on different parts of the brain | |

| Central executive network | involved in high level cognitive functions such as maintaining and using information in working memory, problem solving, and decision making | common in most major psychiatric and neurological disorders, including depression | [107-115] | |

| Default mode network | usually active during specific tasks probed in cognitive science | dysfunction has been characterized by major depression | [116-119] | |

| Silence network | involved in detecting and orienting the most pertinent of the external stimuli and internal events being presented | negative emotional states shows an increase in the right anterior insula during decision making events if the decision has already been made | high activity in the right anterior insula is thought to contribute to the experience of negative and worrisome feelings | [107,116,120,121] |

Table 2: Some of the most studied specific regions of mammalian brain associated to depression.

Antidepressants and their Mechanism of Action

Antidepressants are used for the treatment of depression including dysthymia, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, eating disorders, chronic pain, neuropathic pain, dysmenorrhoea, snoring, migraines, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and sleep disorders [122]. The most important antidepressants are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-nor-epinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs), and nor-adrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSAs). Other drugs used or proposed for the treatment of depression include buprenorphine and St John's wort [123-125].

Some of the most popular antidepressants are called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Some of the most prescribed SSRIs for depression are fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, citalopram and paroxetine. Serotonin and nor-epinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) include venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta). SSRIs and SNRIs can produce headaches, nausea, jitters, or insomnia when people take them. Some people also experience sexual problems with SSRIs or SNRIs. Bupropion that works on dopamine tends to have similar side effects as SSRIs and SNRIs, but it is less likely to cause sexual side effects. However, the risk for seizures of a person can increase.

Tricyclics include imipramine and nortriptyline, are old and powerful antidepressants. They are not used as much today because of their more serious side effects. They may affect the heart, dizziness, drowsiness, dry mouth, and weight gain especially in older adults. They may be dangerous if taken in overdose. These side effects can usually be corrected by changing the dosage or switching to another medication.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can be effective when a person experiences increased appetite and the need for more sleep. MAOIs may help with anxious feelings and other specific symptoms. However, people who take MAOIs must avoid certain foods and beverages that contain a substance called tyramine, certain medications, including some types of birth control pills, prescription pain relievers, cold and allergy medications, and herbal supplements. These substances can interact with MAOIs to increase blood pressure, increased sweating, seizures, hallucinations, muscle stiffness, confusion and other life-threatening conditions.

Augmentation and Combination Strategy

This strategy involves use of different antidepressant drugs in suitable combinations. This strategy has been used to combat SSRI associated fatigue [126]. This strategy has an evidence for the adverse effects although it may be used in clinical practices [127]. The American Psychiatric Association guidelines suggest augmentation, which includes lithium and thyroid augmentation, sex steroids, dopamine agonists, glucocorticoid-specific agents [128].

Modulations in Mammalian Brain by Antidepressant Drugs

Basically antidepressants work in two ways

(1) prevent reuptake of serotonin

(2) block degradation of serotonin by inhibiting monoamine oxidase [129,130]. For the treatment of depression and anxiety, serotonin and nor-epinephrine reuptake inhibiting drugs (SRIs) has been used [129-134]. Hence, the amount of serotonin and norepinephrine increases over a period of time, and help in improving mood and reducing anxiety. In rodents, it has been reported that increase in the transcript level of BDNF in hippocampus and cortex region of brain following antidepressant treatment [135,136].

Some studies have reported the direct incorporation of BDNF in hippocampus of rodents which mimics antidepressant treatment [137,138]. On the other hand, another study on BDNF knock down mice reported that they did not respond to antidepressants and also did not show depressive behaviour [139]. However studies in humans with antidepressant treatment have also been reported an increased BDNF level [140-142]. Fluoxetine (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), administration enhanced neurogenesis and expression of BDNF, which resulted into the enhancement of long term potentiation (LTP) [143,144]. The Val66Met polymorphism in BDNF showed interference with SSRI and neurogenesis [145]. However, the exact molecular mechanism of neurogenesis mediated by BDNF is not understood [146]. Antidepressants alter the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), which gets activated by phosphorylation. CREB protein activates – cAMP-pkA pathway, Cacalmodulin pathway, and MAP-K pathway [147]. It has also reported that BDNF acts through CREB pathway [148,149]. Mouse with over expression of CREB showed decreased depressive behaviour [150].

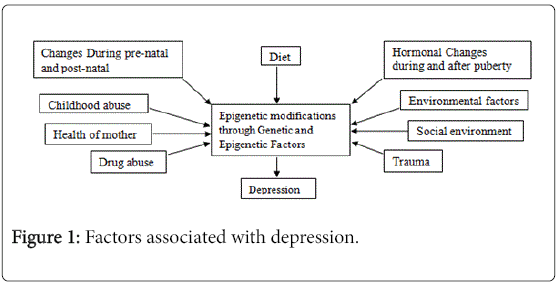

The decreased hippocampal BDNF level has been correlated with stress-induced depressive behaviours [151-155] and treatment with antidepressant(s) enhanced BDNF expression [151,155,156]. In mature neurons the long lasting epigenetic modifications have been shown and reported that it may be implicated in complex neurological disorders [157]. The methylation of histone of DNA can be regulated by stress resulting in down regulation of BDNF III and IV transcripts. However, histone demethylase can also down regulate BDNF transcripts but when antidepressants administered, it promotes histone acetylation and down regulates histone deacetylation [158]. Factors associated with depression mentioned in Figure 1.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy may be the best option for the treatment of mild to moderate depression. However, it may not be enough so, a combination of medication and psychotherapy may be the most effective approach to treat major depression and reducing the chances of it coming back. In addition to application of drugs, several types of psychotherapy practices may help people suffering from depression. Cognitive/behavioral therapy (CBT) helps people with depression to re-structure their negative thoughts in a positive and realistic way. It may also be used to recognize things that may be contributing to the depression. Interpersonal therapy (IPT) helps people to understand and work through troubled relationships that may cause depression. Electroconvulsive therapies (ECT), formerly known as "shock therapy" may be useful in which medication and/or psychotherapy does not relieve.

Treatment of depression with antipsychotic plants / Herbal treatment

The plants proved to have antidepressant property are listed as following: Apocynum venetum, Areca catechu, Cimicifuga racemosa,Centella asiatica, Clitoria ternetea, Hypericum perforatum, Crocus sativus, Bacopa monnieri, Mangolia officinalis, Curcuma longa,, Mimosa pudica, Ginkgo biloba, Ocimum sanctum, Rhazya stricta, Rhizoma acori tatarinowii, Piper methysticum, Withania somnifera,Siphocampylus verticillatus, Oenothera biennis, Morinda officinalis and Perilla frutescens [159]. Their detailed chemical characteristics and antidepressant potential have been summarized in Table 3.

| Plant name | Antidepressant activity shown by the chemical compound present | Part of Plant used | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apocynum venetum | might be due to flavinoids such as hyperoside and isoquercitrin | extract of leaves | [160] | |

| Areca catechu | Alkaloids such as arecaidine, arecoline and few other constituents. | reported to inhibit monoamine oxidase but the dichloromethane fraction from areca nuts showed antidepressant activity in via MAO-A inhibition. | [161-163] | |

| Cimicifuga racemosa | Aqueous Ethanol extract (50 or 100 mg/kg) | [164] | ||

| Centella asiatica | triterpenes | [165] | ||

| Clitoria ternetea | Methanol suspension | activity through serotonergic system | [166] | |

| H. perforatum H. canariens H. grandifolium H. reflexum |

Napthodianthrones (hypericin and pseudohypericin), Phloroglucinols (hyperforin and adhyperforin), flavinoids (flavinol glycoside, viz.rutin quercitrin, isoquercitrin, hyperin,/ hyperoside and aglycones, viz. kaempferol, luteolin, Myrecitin, and quercitin), Xanthones, 1,3,6,7-tetrahydroxylxanthonein trace | 50%aqueous ethanolic extract of Indian plant (100-200 mg/Kg p.o) roots in leaves and stemsMethanol extract of the aerial parts | involved in inhibition of uptake of serotonin, Nor-adrenaline and Dopamine | [167-181] |

| Crocus sativus | hydro-alcoholic extract of Crocus sativus (stigma) | [182,183] | ||

| Bacopa monnieri | alkaloids(brahmine, herpestine) | methanolic stadardized extract | [184] | |

| Mangolia officinalis | Mangolol, and dihydroxydihydromangolol | aqueous extract of the bark | [185] | |

| Curcuma longa | aqueous extracts | mediated through MAO-A inhibition | [186] | |

| Mimosa pudica | aqueous extract from dried leaves | [187] | ||

| Ginkgo biloba | norepinephrine, anddopamine and serotonin | [188-190] | ||

| Ocimum sanctum | Haloperidol and Slpride | Ethanolic extract of leaves, Methanol extract fromroots | involving dopaminergic neurons | [191-196] |

| Rhazya stricta | alkaloids with β carboline nucleus (Akuammidine, rhazimine, and tetrahydrosecamine), flavinoids, namely isorhamnetine, 3 - (6- dirhamnosyl galactoside) -7- rhamnoside and 3- (6 - rhamnosyl galactoside) – 7 – rhamnoside | plant extract | inhibit both MAO-A and MAO-B | [197] |

| Rhizoma acori tatarinowii | [198] | |||

| Piper methysticum | pyrone | aqeous standardizedextract of roots | inhibition of MAO-B mesolimbic dopaminergic neurons |

[199,200] |

| Withania somnifera | glycowithanolides | Standardized extracts of roots | [201-203] | |

| Siphocampylus verticillatus | Hydroalcoholic extract | [204] | ||

| Oenothera biennis | Evening primrose oil obtained from seeds | [205] | ||

| Morinda officinalis | [206,207] | |||

| Perilla frutescens | rosmarinic acid | aqueous extract | [208] |

Table 3: Antipsychotic plants/herbs having antidepressant properties

Conclusion

Depression is known to adversely influence the physiological and psychological activities as it is directly associated with the functions of different regions of the human brain. The molecular and genetic bases of depression include polymorphs of different genes involved in stress and depression as shown in Table 1. The biochemical bases include alterations in the levels of various neurotransmitters and their metabolizing enzymes mentioned as above. The application of current antidepressants described as above help recover the patients suffering from depression but the longer use of these drugs lead to exert serious side effects. Keeping in view the urgent need of specific and target oriented antidepressants, there is immense possibility to explore certain phytochemicals which may prove to be relatively safer and more effective therapeutics to treat depression in future. There are a number of medicinal plants and formulations reported to exhibit antidepressant activity comparable to clinically effective synthetic antidepressants. However, except H perforatum , more detailed clinical studies are required for the plants showing antidepressant activity in animal models.

Acknowledgements

Vivek Kumar Gupta is grateful to the University Grant Commission, New Delhi for providing research scholarship for this work at the Department of Biochemistry, University of Allahabad, India.

References

- Salmans S (1995) Depression: Questions You Have - Answers You Need. People's Medical Society Paper back.

- Leventhal AM, Rehm LP (2005) The empirical status of melancholia: implications for psychology. Clin Psychol Rev 25: 25-44.

- Doghramji K (2003) Treatment strategies for sleep disturbance in patients with depression. J Clin Psychiatry 64 Suppl 14: 24-29.

- Partonen T, Lönnqvist J (1998) Seasonal affective disorder. Lancet 352: 1369-1374.

- Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Grashow R, Gal G, Braehler E, et al. (2014) Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 59: 359-372.

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB (2008) The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33: 693-710.

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Pardo S, Henderson C Jr (2010) Mothers' Differentiation and Depressive Symptoms among Adult Children. J Marriage Fam 72: 333-345.

- Schmidt PJ (2005) Mood, depression, and reproductive hormones in the menopausal transition. Am J Med 118 Suppl 12B: 54-58.

- Rashid T, Heider I (2008) Life events and depression. A of Punjab Med College 2.

- Davey CG, Yücel M, Allen NB (2008) The emergence of depression in adolescence: development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32: 1-19.

- Lewin GR, Barde YA (1996) Physiology of the neurotrophins. Annu Rev Neurosci 19: 289-317.

- Huang EJ, Reichardt LF (2001) Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 677-736.

- West AE, Chen WG, Dalva MB, Dolmetsch RE, Kornhauser JM, et al. (2001) Calcium regulation of neuronal gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 11024-11031.

- Lu B (2003) BDNF and activity-dependent synaptic modulation. Learn Mem 10: 86-98.

- Pattabiraman PP, Tropea D, Chiaruttini C, Tongiorgi E, Cattaneo A, et al. (2005) Neuronal activity regulates the developmental expression and subcellular localization of cortical BDNF mRNA isoforms in vivo. Mol Cell Neurosci 28: 556-570.

- Cunha C, Brambilla R, Thomas KL (2010) A simple role for BDNF in learning and memory? Front Mol Neurosci 3: 1.

- Park H, Poo MM (2013) Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 14: 7-23.

- Benedetti M, Levi A, Chao MV (1993) Differential expression of nerve growth factor receptors leads to altered binding affinity and neurotrophin responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90: 7859-7863.

- Clary DO, Reichardt LF (1994) An alternatively spliced form of the nerve growth factor receptor TrkA confers an enhanced response to neurotrophin 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 11133-11137.

- Lee KF, Davies AM, Jaenisch R (1994) p75-deficient embryonic dorsal root sensory and neonatal sympathetic neurons display a decreased sensitivity to NGF. Development 120: 1027-1033.

- Bibel M, Hoppe E, Barde YA (1999) Biochemical and functional interactions between the neurotrophin receptors trk and p75NTR. EMBO J 18: 616-622.

- Brennan C, Rivas-Plata K, Landis SC (1999) The p75 neurotrophin receptor influences NT-3 responsiveness of sympathetic neurons in vivo. Nat Neurosci 2: 699-705.

- Mischel PS, Smith SG, Vining ER, Valletta JS, Mobley WC, et al. (2001) The extracellular domain of p75NTR is necessary to inhibit neurotrophin-3 signaling through TrkA. J Biol Chem 276: 11294-11301.

- Meyer-Franke A, Wilkinson GA, Kruttgen A, Hu M, Munro E, et al. (1998) Depolarization and cAMP elevation rapidly recruit TrkB to the plasma membrane of CNS neurons. Neuron 21: 681-693.

- Du J, Feng L, Yang F, Lu B (2000) Activity- and Ca(2+)-dependent modulation of surface expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptors in hippocampal neurons. J Cell Biol 150: 1423-1434.

- Park H, Poo MM (2013) Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 14: 7-23.

- Kaplan DR, Miller FD (2000) Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 10: 381-391.

- Corbit KC, Foster DA, Rosner MR (1999) Protein kinase Cdelta mediates neurogenic but not mitogenic activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in neuronal cells. Mol Cell Biol 19: 4209–4218.

- Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Medina JH (2008) BDNF and memory formation and storage. Neuroscientist 14: 147-156.

- Minichiello L (2009) TrkB signalling pathways in LTP and learning. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 850-860.

- Siuciak JA, Lewis DR, Wiegand SJ, Lindsay RM (1997) Antidepressant-like effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Pharmacol Biochem Behav 56: 131-137.

- Shirayama Y, Chen AC, Nakagawa S, Russell DS, Duman RS (2002) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor produces antidepressant effects in behavioral models of depression. J Neurosci 22: 3251-3261.

- Eisch AJ, Bolaños CA, de Wit J, Simonak RD, Pudiak CM, et al. (2003) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the ventral midbrain-nucleus accumbens pathway: a role in depression. Biol Psychiatry 54: 994-1005.

- Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, et al. (2006) Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science 311: 864-868.

- Li Y, Luikart BW, Birnbaum S, Chen J, Kwon CH, et al. (2008) TrkB regulates hippocampal neurogenesis and governs sensitivity to antidepressive treatment. Neuron 59: 399-412.

- Fortin DA, Srivastava T, Dwarakanath D, Pierre P, Nygaard S, et al.(2012) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of CaM-kinase kinase via transient receptor potential canonical channels induces the translation and synaptic incorporation of GluA1-containing calcium-permeable AMPA receptors. J Neurosci 32: 8127–8137.

- Bockaert J, Claeysen S, Bécamel C, Dumuis A, Marin P (2006) Neuronal 5-HT metabotropic receptors: fine-tuning of their structure, signaling, and roles in synaptic modulation. Cell Tissue Res 326: 553-572.

- Lesch KP, Mössner R (1998) Genetically driven variation in serotonin uptake: is there a link to affective spectrum, neurodevelopmental, and neurodegenerative disorders? Biol Psychiatry 44: 179-192.

- Lesch KP, Jatzke S, Meyer J, Stöber G, Okladnova O, et al. (1999) Mosaicism for a serotonin transporter gene promoter-associated deletion: decreased recombination in depression. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 106: 1223-1230.

- Baumgarten HG, Grozdanovic Z (1995) Psychopharmacology of central serotonergic systems. Pharmacopsychiatry 28 Suppl 2: 73-79.

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, et al. (1996) Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 274: 1527-1531.

- Berman ME, Tracy JI, Coccaro EF (1997) The serotonin hypothesis of aggression revisited. Clin Psychol Rev 17: 651-665.

- Mann JJ (1998) The role of in vivo neurotransmitter system imaging studies in understanding major depression. Biol Psychiatry 44: 1077-1078.

- Jans LA, Riedel WJ, Markus CR, Blokland A (2007) Serotonergic vulnerability and depression: assumptions, experimental evidence and implications. Mol Psychiatry 12: 522-543.

- Goodyer IM, Croudace T, Dudbridge F, Ban M, Herbert J (2010) Polymorphisms in BDNF (Val66Met) and 5-HTTLPR, morning cortisol and subsequent depression in at-risk adolescents. Br J Psychiatry 197: 365-371.

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Congdon E, Canli T, Hayden EP (2010) Interaction between 5-HTTLPR and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms on HPA axis reactivity in preschoolers. Biol Psychol 83: 93-100.

- Brummett BH, Boyle SH, Siegler IC, Kuhn CM, Ashley-Koch A, et al. (2008) Effects of environmental stress and gender on associations among symptoms of depression and the serotonin transporter gene linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR). Behav Genet 38: 34-43.

- Margoob MA, Mushtaq D, Murtza I, Mushtaq H, Ali A (2008) Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and treatment response to serotonin reuptake inhibitor (escitalopram) in depression: An open pilot study. Indian J Psychiatry 50: 47-50.

- Kishi T, Okochi T, Tsunoka T, Okumura T, Kitajima T, et al. (2011) Serotonin 1A receptor gene, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: an association study and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 185: 20-26.

- Angles MR, Ocaña DB, MedellÃn BC, Tovilla-Zárate C (2012) No association between the HTR1A gene and suicidal behavior: a meta-analysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 34: 38-42.

- Kishi T, Yoshimura R, Fukuo Y, Okochi T, Matsunaga S, et al. (2013) The serotonin 1A receptor gene confer susceptibility to mood disorders: results from an extended meta-analysis of patients with major depression and bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 263: 105-118.

- González-Castro TB, Tovilla-Zárate C, Juárez-Rojop I, Pool GarcÃa S, Velázquez-Sánchez MP, et al. (2013) Association of the 5HTR2A gene with suicidal behavior: case-control study and updated meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 13: 25.

- Jin C, Xu W, Yuan J, Wang G, Cheng Z (2013) Meta-analysis of association between the -1438A/G (rs6311) polymorphism of the serotonin 2A receptor gene and major depressive disorder. Neurol Res 35: 7-14.

- Gao J, Pan Z, Jiao Z, Li F, Zhao G, et al. (2012) TPH2 gene polymorphisms and major depression--a meta-analysis. PLoS One 7: e36721.

- Serretti A, Chiesa A, Porcelli S, Han C, Patkar AA, et al. (2011) Influence of TPH2 variants on diagnosis and response to treatment in patients with major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 189: 26-32.

- Campos SB, Miranda DM, Souza BR, Pereira PA, Neves FS, et al. (2010) Association of polymorphisms of the tryptophan hydroxylase 2 gene with risk for bipolar disorder or suicidal behavior. J Psychiatr Res 44: 271-274.

- Ates O, Celikel FC, Taycan SE, Sezer S, Karakus N (2013) Association between 1603C>T polymorphism of DBH gene and bipolar disorder in a Turkish population. Gene 519: 356-359.

- Punia S, Das M, Behari M, Mishra BK, Sahani AK, et al. (2010) Role of polymorphisms in dopamine synthesis and metabolism genes and association of DBH haplotypes with Parkinson's disease among North Indians. Pharmacogenet Genomics 20: 435-441.

- Bhaduri N, Mukhopadhyay K (2008) Correlation of plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity with polymorphisms in DBH gene: a study on Eastern Indian population. Cell Mol Neurobiol 28: 343-350.

- Whitmer AJ, Gotlib IH (2012) Depressive rumination and the C957T polymorphism of the DRD2 gene. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 12: 741-747.

- Ambrósio AM, Kennedy JL, Macciardi F, Barr C, Soares MJ, et al. (2004) No evidence of association or linkage disequilibrium between polymorphisms in the 5' upstream and coding regions of the dopamine D4 receptor gene and schizophrenia in a Portuguese population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 125B: 20-24.

- Pattwell SS, Bath KG, Perez-Castro R, Lee FS, Chao MV, et al. (2012) The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism impairs synaptic transmission and plasticity in the infralimbic medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 32: 2410-2421.

- Terracciano A, Tanaka T, Sutin AR, Deiana B, Balaci L, et al. (2010) BDNF Val66Met is associated with introversion and interacts with 5-HTTLPR to influence neuroticism. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 1083-1089.

- Fujii T, Yamamoto N, Hori H, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. (2011) Support for association between the Ser205Leu polymorphism of p75(NTR) and major depressive disorder. J Hum Genet 56: 806-809.

- Lachman HM, Papolos DF, Saito T, Yu YM, Szumlanski CL (1996) Human catechol-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: description of a functional polymorphism and its potential application to neuropsychiatric disorder. Pharmacogenetics 6:243-250.

- Hosák L (2007) Role of the COMT gene Val158Met polymorphism in mental disorders: a review. Eur Psychiatry 22: 276-281.

- Kocabas NA, Faghel C, Barreto M, Kasper S, Linotte S, et al. (2010) The impact of catechol-O-methyltransferase SNPs and haplotypes on treatment response phenotypes in major depressive disorder: a case-control association study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 25: 218-227.

- Cabadak H, Orun O, Nacar C, Dogan Y, Guneysel O, et al. (2011) The role of G protein β3 subunit polymorphisms C825T, C1429T, and G5177A in Turkish subjects with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens 33: 202-208.

- Lu J, Guo Q, Zhang L, Wang W (2012) Association between the G-protein β3 subunit C825T polymorphism with essential hypertension: a meta-analysis in Han Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep 39: 8937-8944.

- Lee HJ, Cha JH, Ham BJ, Han CS, Kim YK, et al. (2004) Association between a G-protein beta 3 subunit gene polymorphism and the symptomatology and treatment responses of major depressive disorders. Pharmacogenomics J 4: 29-33.

- Raybould R, Green EK, MacGregor S, Gordon-Smith K, Heron J, et al. (2005) Bipolar disorder and polymorphisms in the dysbindin gene (DTNBP1). Biol Psychiatry 57: 696-701.

- Breen G, Prata D, Osborne S, Munro J, Sinclair M, et al. (2006) Association of the dysbindin gene with bipolar affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 163: 1636-1638.

- Kim JJ, Mandelli L, Pae CU, De Ronchi D, Jun TY, et al. (2008) Is there protective haplotype of dysbindin gene (DTNBP1) 3 polymorphisms for major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32: 375-379.

- Słopień R, Słopień A, Różycka A, Warenik-Szymankiewicz A, Lianeri M, et al. (2012) The c.1460C>T polymorphism of MAO-A is associated with the risk of depression in postmenopausal women. ScientificWorldJournal 2012: 194845.

- Ward M, Wilson CP, Strain JJ, Horigan G, Scott JM, et al. (2011) B-vitamins, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and hypertension. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 81: 240-244.

- Lizer MH, Bogdan RL, Kidd RS (2011) Comparison of the frequency of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism in depressed versus nondepressed patients. J Psychiatr Pract 17: 404-409.

- Morris MS, Fava M, Jacques PF, Selhub J, Rosenberg IH (2003) Depression and folate status in the US Population. Psychother Psychosom 72: 80-87.

- Chojnicka I, Sobczyk-Kopcioł A, Fudalej M, Fudalej S, Wojnar M, et al. (2012) No association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and completed suicide. Gene 511: 118-121.

- Doghramji K (2003) Treatment strategies for sleep disturbance in patients with depression. J Clin Psychiatry 64 Suppl 14: 24-29.

- Butters MA, Sweet RA, Mulsant BH, Ilyas Kamboh M, Pollock BG, et al. (2003) APOE is associated with age-of-onset, but not cognitive functioning, in late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 18: 1075-1081.

- Steffens DC, Norton MC, Hart AD, Skoog I, Corcoran C, et al. (2003) Apolipoprotein E genotype and major depression in a community of older adults. The Cache County Study. Psychol Med 33: 541-547.

- Binder EB, Bradley RG, Liu W, Epstein MP, Deveau TC, et al. (2008) Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA 299: 1291–1305.

- Roy A, Hodgkinson CA, Deluca V, Goldman D, Enoch MA (2012) Two HPA axis genes, CRHBP and FKBP5, interact with childhood trauma to increase the risk for suicidal behavior. J Psychiatr Res 46: 72-79.

- Appel K, Schwahn C, Mahler J, Schulz A, Spitzer C, et al. (2011) Moderation of adult depression by a polymorphism in the FKBP5 gene and childhood physical abuse in the general population. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 1982-1991.

- Binder EB, Salyakina D, Lichtner P, Wochnik GM, Ising M, et al. (2004) Polymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with increased recurrence of depressive episodes and rapid response to antidepressant treatment. Nature Genet 36: 1319–1325.

- O'Leary JC 3rd, Dharia S, Blair LJ, Brady S, Johnson AG, et al. (2011) A new anti-depressive strategy for the elderly: ablation of FKBP5/FKBP51. PLoS One 6: e24840.

- Wood JG, Joyce PR, Miller AL, Mulder RT, Kennedy MA (2002) A polymorphism in the dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene is associated with "paranoid ideation" in patients with major depression. Biol Psychiatry 51: 365-369.

- Cubells JF, Zabetian CP (2004) Human genetics of plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity: applications to research in psychiatry and neurology. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 174: 463-476.

- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, et al. (2010) A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 67: 446-457.

- Ertenli I, Ozer S, Kiraz S, Apras SB, Akdogan A, et al. (2012) Infliximab, a TNF-α antagonist treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the impact on depression, anxiety and quality of life level. Rheumatol Int 32: 323-330.

- Euteneuer F, Schwarz MJ, Hennings A, Riemer S, Stapf T, et al. (2011) Depression, cytokines and experimental pain: evidence for sex-related association patterns. J Affect Disord 131: 143-149.

- Jope RS, Bijur GN (2002) Mood stabilizers, glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and cell survival. Mol Psychiatry 7 Suppl 1: S35-45.

- Zhang K, Yang C, Xu Y, Sun N, Yang H, et al. (2010) Genetic association of the interaction between the BDNF and GSK3B genes and major depressive disorder in a Chinese population J Neural Trans 117: 393-401.

- Waider J, Araragi N, Gutknecht L, Lesch KP (2011) Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 (TPH2) in disorders of cognitive control and emotion regulation: a perspective. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36: 393-405.

- Zhang X, Gainetdinov RR, Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Burch LH, et al. (2005) Loss-of-function mutation in tryptophan hydroxylase-2 identified in unipolar major depression. Neuron 45: 11-16.

- Delorme R, Durand CM, Betancur C, Wagner M, Ruhrmann S, et al. (2006) No human tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene R441H mutation in a large cohort of psychiatric patients and control subjects. Biol Psychiatry 60: 202-203.

- Ramoz N, Cai G, Reichert JG, Corwin TE, Kryzak LA, et al. (2006) Family-based association study of TPH and TPH2 polymorphisms in autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 141B: 861-867.

- Sacco R, Papaleo V, Hager J, Rousseau F, Moessner R, et al. (2007) Case-control and family-based association studies of candidate genes in autistic disorder and its endophenotypes: TPH2 and GLO1. BMC Med Genet 8: 11.

- Walther DJ, Bader M (2003) A unique central tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Biochem Pharmacol 66: 1673-1680.

- Spielman RS, Weinshilboum RM (1981) Genetics of red cell COMT activity: analysis of thermal stability and family data. Am J Med Genet 10: 279-290.

- Lotta T, Vidgren J, Tilgmann C, Ulmanen I, Melén K, et al. (1995) Kinetics of human soluble and membrane-bound catechol O-methyltransferase: a revised mechanism and description of the thermolabile variant of the enzyme. Biochemistry 34: 4202-4210.

- Pooley EC, Fineberg N, Harrison PJ (2007) The met(158) allele of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder in men: case-control study and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 12: 556-561.

- Sagud M, Mück-Seler D, Mihaljević-Peles A, Vuksan-Cusa B, Zivković M, et al. (2010) Catechol-O-methyl transferase and schizophrenia. Psychiatr Danub 22: 270-274.

- Kocabas NA, Faghel C, Barreto M, Kasper S, Linotte S, et al. (2010) The impact of catechol-O-methyltransferase SNPs and haplotypes on treatment response phenotypes in major depressive disorder: a case-control association study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 25: 218-227.

- Williams-Gray CH, Hampshire A, Barker RA, Owen AM (2008) Attentional control in Parkinson's disease is dependent on COMT val 158 met genotype. Brain 131: 397-408.

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, et al. (2007) Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. The Journal of Neurosci 27: 2349-2356.

- Habas C, Kamdar N, Nguyen D, Prater K, Beckmann CF, et al. (2009) Distinct cerebellar contributions to intrinsic connectivity networks. J Neurosci 29: 8586-8594.

- Menon V (2011) Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci 15: 483-506.

- Petrides M (2005) Lateral prefrontal cortex: architectonic and functional organization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360: 781-795.

- Koechlin E, Summerfield C (2007) An information theoretical approach to prefrontal executive function. Trends Cogn Sci 11: 229-235.

- Miller EK, Cohen JD (2001) An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 167-202.

- Woodward ND, Rogers B, Heckers S (2011) Functional resting-state networks are differentially affected in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 130: 86-93.

- Menon V, Anagnoson RT, Mathalon DH, Glover GH, Pfefferbaum A (2001) Functional neuroanatomy of auditory working memory in schizophrenia: relation to positive and negative symptoms. Neuroimage 13: 433-446.

- Levin RL, Heller W, Mohanty A, Herrington JD, Miller GA (2007) Cognitive deficits in depression and functional specificity of regional brain activity. Cogn Therapy Res 31: 211-233.

- Menon V (2011) Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci 15: 483-506.

- Qin P, Northoff G (2011) How is our self related to midline regions and the default-mode network? Neuroimage 57: 1221-1233.

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, et al. (2001) A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 676-682.

- Cooney RE, Joormann J, Eugène F, Dennis EL, Gotlib IH (2010) Neural correlates of rumination in depression. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 10: 470-478.

- Paulus MP, Stein MB (2006) An insular view of anxiety. Biol Psychiatry 60: 383-387.

- Feinstein JS, Stein MB, Paulus MP (2006) Anterior insula reactivity during certain decisions is associated with neuroticism. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 1: 136-142.

- Burker EJ, Evon DM, Marroquin Loiselle M, Finkel JB, Mill MR (2005) Coping predicts depression and disability in heart transplant candidates. J Psychosom Res 59: 215-222.

- Bodkin JA, Zornberg GL, Lukas SE, Cole JO (1995) Buprenorphine treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 15: 49-57.

- Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L (2008) St John's wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev : CD000448.

- Ernst E (2009) Review: St John's wort superior to placebo and similar to antidepressants for major depression but with fewer side effects. Evid Based Ment Health 12: 78.

- Goss AJ, Kaser M, Costafreda SG, Sahakian BJ, Fu CH (2013) Modafinil augmentation therapy in unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 74: 1101-1107.

- Lam RW, Wan DD, Cohen NL, Kennedy SH (2002) Combining antidepressants for treatment-resistant depression: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 63: 685-693.

- DeBattista C, Lembke A (2005) Update on augmentation of antidepressant response in resistant depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep 7: 435-440.

- Duman RS, Heninger GR, Nestler EJ (1997) A molecular and cellular theory of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 597-606.

- Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, Eisch AJ, Gold SJ, et al. (2002) Neurobiology of depression. Neuron 34: 13-25.

- Kreiss DS, Lucki I (1995) Effects of acute and repeated administration of antidepressant drugs on extracellular levels of 5-hydroxytryptamine measured in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274: 866-876.

- Hervás I, Artigas F (1998) Effect of fluoxetine on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine in rat brain. Role of 5-HT autoreceptors. Eur J Pharmacol 358: 9-18.

- Trillat AC, Malagié I, Mathe-Allainmat M, Anmella MC, Jacquot C, et al. (1998) Synergistic neurochemical and behavioral effects of fluoxetine and 5-HT1A receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol 357: 179-184.

- Malagié I, Trillat AC, Bourin M, Jacquot C, Hen R, et al. (2001) 5-HT1B Autoreceptors limit the effects of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in mouse hippocampus and frontal cortex. J Neurochem 76: 865-871.

- Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS (1995) Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J Neurosci 15: 7539-7547.

- Nibuya M, Nestler EJ, Duman RS (1996) Chronic antidepressant administration increases the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 16: 2365-2372.

- Siuciak JA, Lewis DR, Wiegand SJ, Lindsay RM (1997) Antidepressant-like effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Pharmacol Biochem Behav 56: 131-137.

- Shirayama Y, Chen AC, Nakagawa S, Russell DS, Duman RS (2002) Brain- derived neurotrophic factor produces antidepressant effects in behavioural models of depression. J Neurosci 22: 3251-3261.

- Monteggia LM, Barrot M, Powell CM, Berton O, Galanis V, et al. (2004) Essential role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult hippocampal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 10827-10832.

- Chen B, Dowlatshahi D, MacQueen GM, Wang JF, Young LT (2001) Increased hippocampal BDNF immunoreactivity in subjects treated with antidepressant medication. Biol Psychiatry 50: 260-265.

- Dwivedi Y, Rao JS, Rizavi HS, Kotowski J, Conley RR, et al. (2003) Abnormal expression and functional characteristics of cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:273-282.

- Karege F, Vaudan G, Schwald M, Perroud N, La Harpe R (2005) Neurotrophin levels in postmortem brains of suicide victims and the effects of antemortem diagnosis and psychotropic drugs. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 136: 29-37.

- Wang JW, David DJ, Monckton JE, Battaglia F, Hen R (2008) Chronic fluoxetine stimulates maturation and synaptic plasticity of adult-born hippocampal granule cells. J Neurosci 28: 1374-1384.

- Bianchi P, Ciani E, Guidi S, Trazzi S, Felice D, et al. (2010) Early pharmacotherapy restores neurogenesis and cognitive performance in the Ts65Dn mouse model for Down syndrome. J Neurosci 30:8769-8779.

- Bath KG, Jing DQ, Dincheva I, Neeb CC, Pattwell SS, Chao MV, et al. (2012) BDNF Val66Met impairs fluoxetine-induced enhancement of adult hippocampus plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology 37: 1297-1304.

- Ninan I, Bath KG, Dagar K, Perez-Castro R, Plummer MR, et al. (2010) The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism impairs NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 30:8866-8870.

- Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME (1999) CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 821-861.

- Nibuya M, Nestler EJ, Duman RS (1996) Chronic antidepressant administration increases the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 16: 2365-2372.

- Conti AC, Cryan JF, Dalvi A, Lucki I, Blendy JA (2002) cAMP response element-binding protein is essential for the upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcription, but not the behavioral or endocrine responses to antidepressant drugs. J Neurosci 22: 3262-3268.

- Chen AC, Shirayama Y, Shin KH, Neve RL, Duman RS (2001) Expression of the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in hippocampus produces an antidepressant effect. Biol Psychiatry 49: 753-762.

- Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS (1995) Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J Neurosci 15: 7539-7547.

- Smith MA, Makino S, Kvetnansky R, Post RM (1995) Stress and glucocorticoids affect the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 mRNAs in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 15: 1768-1777.

- Vaidya VA, Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK, Duman RS (1997) 5-HT2A receptor-mediated regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the hippocampus and the neocortex. J Neurosci 17: 2785-2795.

- Duman RS (2004) Role of neurotrophic factors in the etiology and treatment of mood disorders. Neuromolecular Med 5: 11-25.

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM (2006) A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 59: 1116-1127.

- Russo-Neustadt A, Beard RC, Cotman CW (1999) Exercise, antidepressant medications, and enhanced brain derived neurotrophic factor expression. Neuropsychopharmacology 21: 679-682.

- Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, et al. (2006) Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci 9: 519-525.

- Tsankova N, Renthal W, Kumar A, Nestler EJ (2007) Epigenetic regulation in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 355-367.

- Dhingra D, Sharma A (2005) A review on antidepressant plants. Nat Produc Radiance 5: 144-152.

- Butterweck V, Nishibe S, Sasaki T, Uchida M (2001) Antidepressant effects of apocynum venetum leaves in a forced swimming test. Biol Pharm Bull 24: 848-851.

- Dar A, Khatoon S, Rahman G, Atta-Ur-Rahman (1997) Anti-depressant activities of Areca catechu fruit extract. Phytomedicine 4: 41-45.

- Dar A, Khatoon S (1997b) Antidepressant effect of ethanol extract of Areca catechu in Rodents. Phytother Res 11: 174-176.

- Dar A, Khatoon S (2000) Behavioral and biochemical studies of dichloromethane fraction from the Areca catechu nut. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 65: 1-6.

- Winterhoff H, Spengler B, Christoffel V, Butterweck V, Löhning A (2003) Cimicifuga extract BNO 1055: reduction of hot flushes and hints on antidepressant activity. Maturitas 44 Suppl 1: S51-58.

- Chen Y, Han T, Qin L, Ui RY, Zheng H (2003) Effect of total Triterpenes from Centella asiatica on the depression behavior and concentration of amino acid in forced swimming mice. J Chinese Med Mat 26: 870-873.

- Jain NN, Ohal CC, Shroff SK, Bhutada RH, Somani RS, et al. (2003) Clitoria ternatea and the CNS. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 75: 529-536.

- Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, Pauls A, Weidenhammer W, et al (1996) St. John's wort for depression -an overview and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMJ 313: 253-258.

- Kumar V, Singh PN, Jaiswal AK, Bhattacharya SK (1999) Antidepressant activity of Indian Hypericum perforatum Linn in rodents. Indian J Exp Biol 37: 1171-1176.

- De Vry J, Maurel S, Schreiber R, de Beun R, Jentzsch KR (1999) Comparison of hypericum extracts with imipramine and fluoxetine in animal models of depression and alcoholism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 9: 461-468.

- Khalifa AE (2001) Hypericum perforatum as a nootropic drug: enhancement of retrieval memory of a passive avoidance conditioning paradigm in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 76: 49-57.

- Bystrov NS, Chernov BK, Dobrynin VN, Kolosov MN (1975) The structure of Hyperforin. Tetrahedran Lett 16: 2791-2794.

- Dorosseiv I (1985) Determination of flavinoids in Hypericum perforatum. Pharmazie 40:585-586.

- Sparenberg B, Demisch L, Holzl J (1993) Investigations of the antidepressive effect of St. John’s wort. Pharm Ztg wiss 6: 50-54.

- Müller WE, Singer A, Wonnemann M, Hafner U, Rolli M, et al. (1998) Hyperforin represents the neurotransmitter reuptake inhibiting constituent of hypericum extract. Pharmacopsychiatry 3 Suppl 1: 16-21.

- Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharya SK, Wonnemann M, Singer A, Müller WE (1998) Hyperforin as a possible antidepressant component of hypericum extracts. Life Sci 63: 499-510.

- Barnes J, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD (2001) St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): a review of its chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. J Pharm Pharmacol 53: 583-600.

- Singer A, Wonnemann M, Müller WE (1999) Hyperforin, a major antidepressant constituent of St. John's Wort, inhibits serotonin uptake by elevating free intracellular Na+1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290: 1363-1368.

- Calapai G, Crupi A, Firenzuoli F, Inferrera G, Squadrito F, et al. (2001) Serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine involvement in the antidepressant action of hypericum perforatum. Pharmacopsychiatry 34: 45-49.

- Authors Klemow KM, Bartlow A, Crawford J, Kocher N, Shah J, et al. () Medical Attributes of St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum). Medical Attributes of St .

- Sánchez-Mateo CC, Prado B, Rabanal RM (2002) Antidepressant effects of the methanol extract of several Hypericum species from the Canary Islands. J Ethnopharmacol 79: 119-127.

- Sanchez-Mateo CC, Prado B, Rabanal RM (2002) Antidepressant like effect of the methanol extract of several Hypericum Speceis from Canary Island. J Ethnopharmacol 79: 119-127.

- Akhondzadeh S, Fallah-Pour H, Afkham K, Jamshidi AH, Khalighi-Cigaroudi F (2004) Comparison of Crocus sativus L. and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a pilot double-blind randomized trial [ISRCTN45683816]. BMC Complement Altern Med 4: 12.

- Noorbala AA, Akhondzadeh S, Tahmacebi-Pour N, Jamshidi AH (2005) Hydro-alcoholic extract of Crocus sativus L. versus fluoxetine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized pilot trial. J Ethnopharmacol 97: 281-284.

- Sairam K, Dorababu M, Goel RK, Bhattacharya SK (2002) Antidepressant activity of standardized extract of Bacopa monniera in experimental models of depression in rats. Phytomedicine 9: 207-211.

- Nakazawa K, Sun LD, Quirk MC, Rondi-Reig L, Wilson MA, et al. (2003) Hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors are crucial for memory acquisition of one-time experience. Neuron 38: 305-315.

- Yu ZF, Kong LD, Chen Y (2002) Antidepressant activity of aqueous extracts of Curcuma longa in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 83: 161-165.

- Molina M, Contreras CM, Tellez-Alcantara P (1999) Mimosa pudica may possess antidepressant actions in the rat. Phytomedicine 6: 319-323.

- Shah ZA, Sharma P, Vohora SB (2003) Ginkgo biloba normalises stress-elevated alterations in brain catecholamines, serotonin and plasma corticosterone levels. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 13: 321-325.

- Trick L, Stanley N, Rigney U, Hindmarch I (2004) A double-blind, randomized, 26-week study comparing the cognitive and psychomotor effects and efficacy of 75 mg (37.5 mg b.i.d.) venlafaxine and 75 mg (25 mg mane, 50 mg nocte) dothiepin in elderly patients with moderate major depression being treated in general practice. J Psychopharmacol 18: 205-214.

- Qin XS, Jin KH, Ding BK, Xie SF, Ma H (2005) Effects of extract of Ginkgo biloba with venlafaxine on brain injury in a rat model of depression. Chin Med J (Engl) 118: 391-397.

- Dixit KS, Srivastava M, Srivastava AK, Singh SP, Singh N (1985) Effect of Ocimum sanctum on stress induced alterations upon some brain neurotransmitters and enzyme activity. Proc XVIIIth Annual Conference of Indian Pharmacological Society, JIPMER, Pondicherry: 57.

- Singh N (1986) A pharmaco-clinical evaluation some ayurvedic crude plant drugs as anti- stress agents and their usefulness in some stress disease of man. Ann Nat Acad Ind Med 2: 14-26.

- Sakina MR, Dandiya PC, Hamdard ME, Hameed A (1990) Preliminary psychopharmacological evaluation of Ocimum sanctum leaf extract. J Ethnopharmacol 28: 143-150.

- Singh N, Mishra N, Srivastava AK, Dixit KS, Gupta GP (1991) Effect of anti stress plant on biochemical changes during stress reaction. Ind J Pharmacol 23:137-142.

- Singh N, Mishra N (1993) Experimental methods-Tools for assessment of anti stress activity in medicinal plants. J Biol Chem Res 12:124-127.

- Maity TK, Mandal SC, Saha BP, Pal M (2000) Effect of Ocimum sanctum roots extract on swimming performance in mice. Phytother Res 14: 120-121.

- Ali BH, Bashir AK, Tanira MO (1998) The effect of Rhazya stricta Decne, a traditional medicinal plant, on the forced swimming test in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 59: 547-550.

- Li M, Chen H (2001) Antidepressant effect of water decoction of Rhizoma acori tatarinowii in the behavioural despair animal models of depression. Zhong Yao Cai 24:40-41.

- Baum SS, Hill R, Rommelspacher H (1998) Effect of kava extract and individual kavapyrones on neurotransmitter levels in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 22: 1105-1120.

- Wheatley D (2001) Kava and valerian in the treatment of stress-induced insomnia. Phytother Res 15: 549-551.

- Bhattacharya SK, Bhattacharya A, Sairam K, Ghoshal S (2000) Anxiolytic-antidepressant activity of Withania sominifera glycowithanolides: An experimental study. Phytomedicine7:463 469.

- Singh A, Naidu PS, Gupta S, Kulkarni SK (2002) Effect of natural and synthetic antioxidants in a mouse model of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Med Food 5: 211-220.

- Bhattacharya SK, Muruganandam AV (2003) Adaptogenic activity of Withania somnifera: an experimental study using a rat model of chronic stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 75: 547-555.

- Rodrigues AL, Da Silva GL, Mateussi AS, Fernandes ES, Miguel OG, et al. (2002) Involvement of monoaminergic system in the antidepressant-like effect of the hydroalcoholic extract of Siphocampylus verticillatus. Life Sci 70: 1347-1358.

- Kaur G, Kulkarni SK (1998) Reversal of forced swimming- induced chronic fatigue in mice by antidepressant and herbal psychotropic drugs. Indian Drugs 35: 771-777.

- Zhang ZQ, Yuan L, ZhaoN, Xu YK, Yang M, et al. (2000) Antidepressant effect of the extracts of the roots of Morinda officinalis in rats and mice. Chin Pharm J 35: 739-741.

- Zhang ZQ, Huang Sj, Yuan L, Zha N, Xu YK, et al. (2001) Effect of Morinda officinalis oligosaccharides on performance of the swimming tests in mice and rats and the learned helplessness paradigm in rats. Chin J Pharmacol Toxicol 15: 262-265.

- Takeda H, Tsuji M, Matsumiya T, Kudo M (2002) Identification of rosmarinic acid as a novel anti-depressive substance in the leaves of Perilla frutescens Briton var. acuta Kudo (Perillae Herba). Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi 22: 15-22.

Citation: Sharma B, Gupta VK (2016) Modulations of Mammalian Brain Functions by Antidepressant Drugs: Role of Some Phytochemicals as Prospective Antidepressants. Evidence Based Medicine and Practice 1: 103. DOI: 10.4172/2471-9919.1000103

Copyright: © 2016 Sharma B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13504

- [From(publication date): 4-2016 - Apr 02, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 12545

- PDF downloads: 959