Medically Assisted Reproduction (MAR) in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Received: 21-Oct-2020 / Accepted Date: 04-Nov-2020 / Published Date: 11-Nov-2020 DOI: 10.4172/2476-2024.S1.001

Abstract

The current COVID-19 pandemic poses a unique challenge for the provision of standard healthcare services. Medically Assisted Reproduction (MAR) includes interventions aimed to treat infertility, or provide services to single women or same sex couples wishing to conceive. The right to a family is a human right, as stated by the World Health Organization (WHO), and infertility is considered a disease, often time-sensitive; thus, delaying timely treatment can severely affect a person’s probability to get pregnant.

We assessed the impact of the pandemic on fertility treatment from a global perspective, describing the timeline of events, the initial reaction and recommendations of scientific societies, along with further guidelines on re-commencing MAR care in a safe environment. We describe the safety protocol put in place in our clinic, its results, and we discuss the current literature evidence on the effect of SARS-CoV-2 on pregnancy, vertical transmission and neonatal health.

Keywords: Medically assisted reproduction; MAR; COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; IVF; Pandemic; ART

About the Study

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly unfolded since its outbreak in Hubei, China in late 2019, and according to the Johns Hopkins University tracking dashboard, it has now spread around 189 countries and regions, affecting more than 40 million people, and causing over a million deaths worldwide [1].

Standard health care around the world has been affected by the pandemic, due to the necessary prioritization of essential medical services, warranting the availability of critical medical supplies, devices and staff where it is most needed. As the pandemic evolves and persists, it has become more and more evident that standard medical care has taken a heavy toll from the SARS-CoV2 outbreak, affecting standard medical care such as cardiovascular disease, or cancer therapy [2].

Medically Assisted Reproduction (MAR) is currently defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) glossary [3] as “Reproduction brought about through various interventions, procedures, surgeries and technologies to treat different forms of fertility impairment and infertility. These include ovulation induction, ovarian stimulation, ovulation triggering, all ART procedures, uterine transplantation and intra-uterine, intracervical and intravaginal insemination with semen of husband/partner or donor”.

MAR encompasses the treatment of women or couples suffering from infertility-a condition that affects 3.5%-16.7% of the population in developed western countries [4] but it also includes fertility care given to single women or same-sex couples that need Assisted Reproduction irrespective of the existence of a disease. Treatments include ovulation induction, Intrauterine Inseminations (IUIs) In Vitro Fertilization (IVF/ICSI), gamete cryopreservation, egg donation, and frozen embryo transfers. Thus, infertility is currently defined a disease by the WHO [5], but also, access to fertility care is considered part of the right of individuals and couples to found a family, or decide when or how to have their children [6].

Additionally, reproductive performance, whether natural or through MAR, is critically affected by female age, especially after 35 to 37 years of age, when follicular depletion accelerates, compromising ovarian reserve. Social and cultural trends in the last three decades have resulted in delayed childbearing, and MAR registries around the world have clearly reflected this trend [7] with pregnancy rates stable around 30%-40%, despite significant scientific breakthroughs, improvements in hormonal stimulation and embryo culture technique and equipment in the laboratory.

Thus, only considering the age of the woman, fertility care is time sensitive, and delays in therapy can result in declining success rates, and increasing psychological burden. Moreover, infertility can be associated with other co-morbidities like tubal disease, obesity, endocrine disorders, uterine fybroids, polyps or endometriosis, that need a multidisciplinary and coordinated approach in conjunction with surgery and/or MAR treatments. Consequently, timely diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are critical to success during fertility care, and delays will inevitably cause a negative impact on patients.

MAR practices are globally widespread, however, significant differences are observed between countries due to regional differences in access and availability of services, or because of social, political, philosophical or religious reasons [8]. These circumstances can further affect and distort the normal provision of care during a pandemic, because in some places neither state nor private insurance coverage of MAR is mandatory, or these procedures are not considered “essential” medical services.

The first reaction of the MAR community to the pandemic was a “precautionary approach” taking into consideration the lack of knowledge about the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus on the reproductive process. No data was available on the presence of the virus in human gametes, its impact in early pregnancy, vertical transmission during the second and third trimester, obstetrical or neonatal morbidity/ mortality, or effects on lactation. Some of the initial guidance was also influenced by information on the significant obstetrical impact of two previous coronavirus outbreaks (SARS-CoV and MERS), which showed maternal mortality rates of 25% and 23% respectively, although a total of only 25 pregnancies were communicated during those outbreaks.

During the months of March and April 2020, Scientific Societies around the world issued guidance statements for reproductive medicine specialists and MAR Centers. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) [9] and the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) [10], recommended the following measures:

• Suspend the initiation of new treatment cycles

• Consider embryo cryopreservation and cancellation of transfers in ongoing cycles.

• Continue treatment and care in ongoing cycles considered urgent due to medical reasons.

• Suspend elective surgeries and non-urgent diagnostic procedures.

• Increase telemedicine alternatives.

In May 2020, while Europe and America where seeing a growing number of cases and local lockdowns were in place, MAR centers began considering re-opening practices under strict protocols, in compliance with social distancing and personal hygiene recommendations. Use of personal protective equipment, and continuous monitoring of patients and personnel through triage/testing procedures were encouraged. New guidance was made available, and other Societies followed. In June, ESHRE, ASRM and the International Federation of Fertility Societies (IFFS) issued a joint statement [11] declaring the need for continued reproductive care during the pandemic, related to the condition of infertility as a time-sensitive disease and declaring reproduction as an essential human right transcending race, gender, sexual orientation or country of origin. Continuous monitoring, reporting and research was recommended. Others, early in the pandemic, had proposed a continuation of treatments in advanced maternal age, and poor ovarian reserve patients, a particularly low prognosis and time-sensitive subgroup of MAR candidates [12].

The ESHRE COVID-19 working group surveyed the activity of MAR centers across Europe and summarized the data aligned with epidemiological data from the European Center for Disease Control on the number of COVID cases per country. The work revealed a large variation in the status of MAR activity depending on local epidemic dynamics within countries, however, by the end of May most of the European countries had resumed fertility cycles, and fertility preservation treatments for oncologic patients had remained available during the pandemic [13]. A more recent publication by the same working group has updated previous recommendations and offers guidance and safety measures for safe reopening of clinics [14] also surveyed MAR activity worldwide during the month of April, in 97 countries, concluding that the reproductive health community has followed guidelines and has been largely responsive to public health and individual patient concerns [15].

Along with the evolving pandemic, various organizations have been reporting and monitoring their results and opening registries on the prognosis and evolution of pregnancies affected by COVID-19. ESHRE is collecting data on a simple online survey in their webpage, that offers case-by-case reporting on outcomes of MAR pregnancies with a COVID-19 diagnosis confirmed [10], and the upcoming 9th edition of IFFS Surveillance, a triennial survey reporting on global MAR activity, policies and regulations will include data on activity during the pandemic (Steve Ory, personal communication).

In the meantime, a growing body of evidence in the literature is showing reassuring data on the maternal and neonatal outcome of pregnancies affected by COVID-19, with isolated cases of vertical transmission limited to severely ill mothers, with an average pooled incidence estimated in 16 per 1000 newborns [16]. A recent “living” systematic review and meta-analysis scheduled to continuously monitor and follow up COVID-19 pregnancies, reported results on 11,432 pregnant women from 77 studies spanning from December 2019 through June 2020 [17]. The paper showed that pregnant women with COVID-19 infection are less likely to manifest symptoms of fever and myalgia and are more likely to present preterm birth and an increase in neonatal admissions. Risk factors for severe COVID in pregnancy included increase maternal age, high body mass index, and pre-existing co-morbidities.

Currently, MAR centers worldwide are following guidelines from the constantly updated statements of appointed task forces from the Scientific Societies. Overall, these emphasize on general recommendations of personal hygiene, social distancing and face masking, but specifically triage, testing protocols and indications, and personnel reorganization, plus telemedicine and emergency protocols.

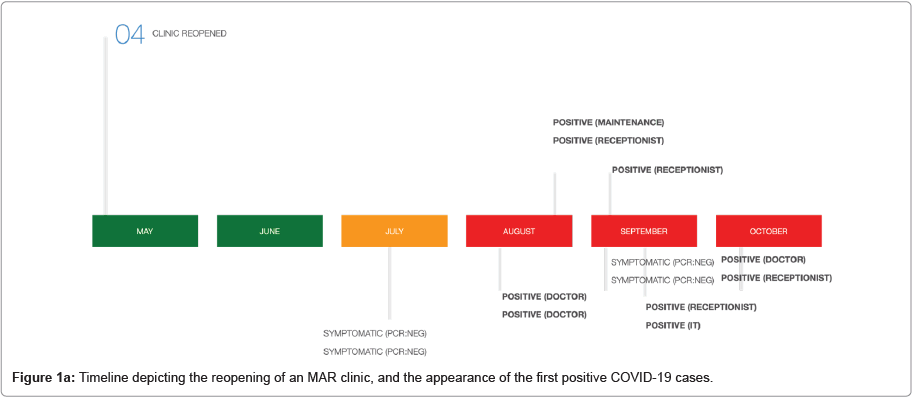

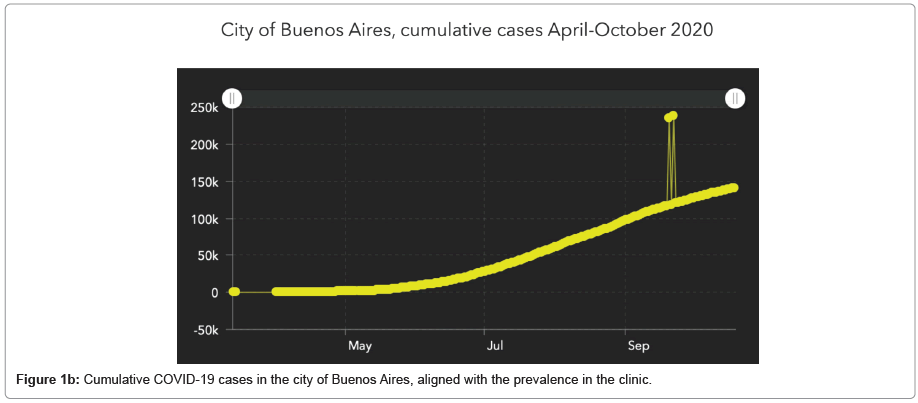

At our clinic (unpublished data), an infectious disease committee was established, and developed a comprehensive program including training, reading materials and infographic tools for personnel, and reorganized everyday work to adapt to the current situation. All staff at the clinic (medical and non-medical) is triaged daily through a digital questionnaire and an official app as well, and follow similar precautions, with organization of working teams ready for replacement of sick individuals. Consultations are preferentially managed through telemedicine platforms, especially for initial consultations, review of reports and medical studies, or second opinions. If done in-person, consultations and ultrasound monitoring are now done using face masks, and eye protection through goggles or a face shield. Consultations are scheduled to avoid waiting room overcrowding, and must ideally have a 15 minute limit, partners are not allowed to attend, and every patient entering the clinic is triaged through a digital questionnaire received by mail upon confirmation of the scheduled visit. Once in the clinic, the triage is reviewed and a temperature check is done. In this way, after six months working under this protocol, we had 9 contagions (Figure 1a), all related to their households and close relatives. The pattern followed the dynamics of the epidemiological curve in our city (Figure 1b) have avoided in-house outbreaks that would be significant challenges remain in our knowledge of COVID-19 disease and its consequences in reproduction, MAR treatments, and pregnancy thereafter. Obstetrical and neonatal prognosis is reassuring based on the current published data, with a slight increase in preterm birth and neonatal admissions and an extremely low vertical transmission rate, limited to severe cases.

A prudent approach from the doctor and the clinic should be in place, including comprehensive discussion with patients and prospective parents on the risks and benefits of getting pregnant during the pandemic, offering alternative treatments including gamete or embryo cryopreservation, and in eligible cases, postponing treatment.

However, family foundation is a human right and infertility is a disease, very often time-sensitive, and delaying treatment under the argument of a pandemic is not justified by current evidence. It has decimated our staff and increased the risk of propagation to patients.

References

- Coronavirus Resource Center COVID-19 (2020) Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University.

- Rosenbaum L (2020) The untold toll-the pandemic’s effects on patients without COVID-19. N Engl J Med 382: 24.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, De Mouzon J, et al. (2017) The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Hum Reprod 32: 1786-1801.

- Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG (2007) International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod 22: 1506-1512.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Dickens BM, Dughman-Manzur S (2013) Human rights to in vitro fertilization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 123: 86-89.

- Dyer S, Chambers GM, de Mouzon J, Nygren KG, Zegers-Hochschild F, et al. (2020) International committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technologies world report: Assisted reproductive technology 2012. Hum Reprod 31: 1-52.

- (2019) International Federation of Fertility Societies’ Surveillance (IFFS) 2019: Global Trends in Reproductive Policy and Practice. Global Reproductive Health 4: 29.

- ASRM (2020) Patient management and clinical recommendations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

- European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (2020) COVID-19 and ART.

- Veiga A, Gianaroli L, Ory S, Horton M, Feinberg E, et al. (2020) Assisted reproduction and COVID-19: A joint statement of ASRM, ESHRE and IFFS. Hum Reprod Open 114: 484-485.

- Alviggi C, Esteves SC, Orvieto R, Conforti A, La Marca A, et al. (2020) COVID-19 and assisted reproductive technology services: Repercussions for patients and proposal for individualized clinical management. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 18: 45.

- Vermeulen N, Ata B, Gianaroli L, Lundin K, Mocanu E, et al. (2020) A picture of medically assisted reproduction activities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. Hum Reprod Open 2020: hoaa035.

- Gianaroli L, Ata B, Lundin K, Rautakallio-Hokkanen S, Tapanainen JS, et al. (2020) The calm after the storm: Re-starting ART treatments safely in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Reprod.

- Ory S, Miller K, Horton M, Giudice L (2020) The global impact of COVID-19 on infertility services. Glob Reprod Health 2: 43.

- Goh XL, Low YF, Ng CH, Amin Z, Ng YP (2020) Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 vertical transmission: A meta analyisis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2020: 319791.

- Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, Yap M, Chatterjee S, et al. (2020) Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: Living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 370: m3320.

Citation: Horton M (2020) Medically Assisted Reproduction (MAR) in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Diagnos Pathol Open S1: 001. DOI: 10.4172/2476-2024.S1.001

Copyright: © 2020 Horton M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1869

- [From(publication date): 0-2020 - Apr 03, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1153

- PDF downloads: 716