Research Article Open Access

Mapping Professional Development Activities Involving Clinical Preventive Care for Adolescents by Oral Health Therapists Working in Public Oral Health Services NSW, Australia

Masoe AV1*, Blinkhorn AS2, Taylor J1 and Blinkhorn FA1

1School of Health Sciences, Health and Medicine, Oral Health, University of Newcastle, Ourimbah 2258, NSW, Australia

2Department of Population Oral Health, Dentistry, University of Sydney, 1 Mons Road, Westmead 2145, NSW, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Angela V Masoe

School of Health Sciences

Health and Medicine

Oral Health, University of Newcastle

Ourimbah 2258, P.O.Box 729

Queanbeyan 2620, NSW, Australia

Tel: 61 2 6128 9852

E-mail: Angela.Masoe@ gsahs.health. nsw.gov.au

Received Date: May 28, 2015; Accepted Date: July 21, 2015; Published Date: July 28, 2015

Citation: Masoe AV, Blinkhorn AS, Taylor J, Blinkhorn FA (2015) Mapping Professional Development Activities Involving Clinical Preventive Care for Adolescents by Oral Health Therapists Working in Public Oral Health Services NSW, Australia. J Child Adolesc Behav 3:224. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000224

Copyright: © 2015 Masoe AV, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

Background: Continuing professional development (CPD) is an essential component for dental Therapists and oral health Therapists to uphold registration with the Australian Dental Board. Evidence of CPD is considered an assurance of Therapists scientific clinical knowledge and competence to provide quality care to patients. Many vulnerable adolescents are at risk of dental caries and periodontal disease due to poor oral hygiene self-care practices and dietary behaviours. Therapists have a pivotal role to play in the provision of scientific-based clinical preventive care and advice to encourage adolescents towards oral health self-efficacy for lifelong benefits. The aim of this study was to record CPD clinical preventive care activities focused on adolescents undertaken by Therapists working in NSW Public Oral Health Services. Methods: A cross-sectional self-administered survey using a postal questionnaire was used to record the continuing professional development activities of Therapists working in all NSW Local Health Districts (LHDs) in relation to clinical preventive care offered to adolescents. Results: One hundred and seventeen Therapists (64.6%) responded to the survey. Approximately 20% of respondents had not undertaken CPD on preventive care for adolescents in the last two years, 33.3% documented less than 5 hours, and 35.1% more than 10 hours. Almost 88 percent of respondents received their CPD from within their LHDs, and ranked peer reviews and team building events for sharing information as key strategies to enhance their ability to offer clinical preventive care to adolescents. Conclusion: This study has shown that one third of all Therapists had received less than 5 hours CPD focussing on helping adolescents maintain their oral health in the last 2 years. In order to support Therapists continuing professional education, inter-professional peer reviews in partnership with dentists, visiting dental specialists, and whole team approaches should be regularly undertaken. In addition scoping of other modes of education such as the Information Communication Technology for broader reach are worthy of further investigation.

Keywords

Adolescent oral health; Preventive care; Continuing professional development; Dental and oral health therapists

Background

Despite the scientific evidence of the value of clinical preventive care and oral health education strategies to control oral disease over the past decade, researchers have reported a slow uptake by dental practitioners’ to embed the evidence into their clinical practice for improved patient health outcomes [1-4]. Continuing professional development (CPD) for health professionals is a strategic approach to ensure quality health care [5]. However, limited resources and high demands of the dental and oral health practitioners for education and training at multiple levels, has been reported as placing strain on the providers of scientific based CPD [6].

The definition provided by the Dental Board of Australia for CPD is: “the means by which members of the profession maintain, improve and broaden their knowledge, expertise and competence, and develop the personal and professional qualities required throughout their professional lives” [7]. The British General Dental Council guidelines are somewhat more descriptive and define CPD as: “lectures, seminars, courses, individual study and other activities that can be included in your CPD record if it can be reasonably expected to advance your professional development as a dentist or dental care professional and is relevant to your practice or intended practice” [8].

Evidence of dental practitioner’s ongoing CPD is considered an assurance of their scientific clinical knowledge and competence to provide quality oral health care to all patients [7]. Efforts to improve clinical practice have included audits and feedback reports, evidence-based guidelines, total quality management, economic and organizational changes underpinned by professional education and development [9,10]. According to Grol [9], the most reliable means for improving quality of care, is to be informed by scientific literature, in conjunction with clinical practice insight to stimulate informed recommendations to assist health professionals to decide on the most appropriate care and processes to promote education, and decrease variations in health care services and cost inefficiencies [11,12].

The literature on CPD states that lifelong learning is a fundamental mechanism to enhance clinical governance principles to ensure the public’s confidence in dental and oral health professionals [13-15]. In the State of New South Wales (NSW), the Ministry of Health funds the Local Health Districts (LHDs) to provide free clinical and preventive care for all children and adolescents under 18 years of age [11]. The majority of this care is provided by dental Therapists and oral health Therapists (Therapists). The LHDs as the clinical governing agency are responsible for ensuring that all dental practitioners are compliant with the recommended CPD goals to maintain their registration to practice [11,12]. Therapists under the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation National Law have a mandatory requirement to participate in CPD to maintain registration with the Dental Board of Australia [7]. According to the CPD requirements, dental practitioners must complete a minimum of 60 hours over 3 years with 80 per cent to be clinically or scientifically based [7]. A study by Hopcraft et al. [13] reported the rationale for dental practitioners undertaking CPD in the State of Victoria, however, no reference was made to Therapists’ clinical preventive care CPD. Nonetheless, the study reported that the topic of the CPD course was a main motivator for Therapists to attend courses. Although the dental literature has reported broadly on dental practitioners CPD patterns, the majority of research has focused on dentists [15-17] with Hopcraft et al. [13] study being one of the few to include Therapists. There is a dearth of information on the CPD activities of Therapists working within NSW Public Oral Health Services especially in relation to their perceptions of CPD focused on clinical preventive care and managing the adolescent patient to support their compliance with NSW Health oral preventive policies [18-20]. Therefore this study was undertaken to scope and record Therapists participation and perceptions of CPD activities pertaining to clinical preventive care for adolescents.

Methods

A cross-sectional self-administered postal survey, administered by NSW Health, was sent to Therapists working within all the fifteen Local Health Districts (LHDs). The 17 item questionnaire was developed from focus group pilot work with Therapists in four NSW LHDs [21] which explored influencing factors for the provision of preventive care to adolescents, and encompassed Continuing Professional Development questions pertaining to the clinical preventive care of adolescents. Demographic information about the participants was collected and Likert scales were used as the measurement instrument to determine whether the participants strongly disagreed or strongly agreed (strongly disagree =1 to strongly agree = 5) with a series of statements [22].

The contact details for all Therapists working within the NSW Public Oral Health Services were obtained by contacting the directors of each of the fifteen LHDs. One hundred and ninety two Therapists were initially identified, and questionnaires containing return postagepaid envelopes were mailed with reminder letters being sent to nonrespondents at 2 weeks, 1 month, 2 months and 3 months after the initial mailing.

The data were analysed using the IBM SPSS package [23]. The differences between the mean responses were tested using the independent sample T-test for equality of variances.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Hunter New England Local Health District Lead Health and Research Ethics Committee (HREC) Reference No. 12/02/15/5.04 and all fifteen Local Health Districts.

Results

Further information regarding the number of Therapists working in NSW Public Oral Health Services was received after the survey distribution. The original sample of 192 was reduced by 11 due to job changes and retirements, giving a final sample of 181, of whom 117 (64.6%) responded. More (61.5%; N=72) respondents worked in rural LHDs compared to metropolitan LHDs (38.4%; N=45).

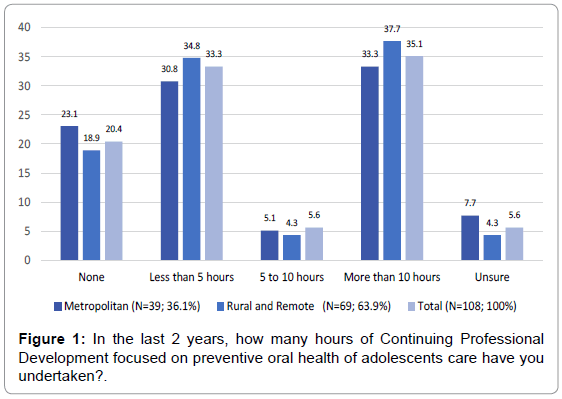

Figure 1 shows that just over 20 per cent of the respondents had not undertaken any CPD on preventive care for adolescents, 33.3 per cent had received less than 5 hours of CPD and over 35.1 per cent had received more than 10 hours of CPD, with rural and remote Therapists (37.7%) reporting slightly more than their metropolitan counterparts (33.3%).

Table 1 illustrates that respondents received most information about the preventive care of adolescents from in-service training provided by their LHDs (87.9%), followed by external professional oral health conferences (47%) and visiting dental corporate companies (41%). Therapists (39.3%) indicated that they had accessed preventive care information on-line from oral health websites; with rural and remote (27.3%), using this form of information more frequently than metropolitan respondents. A further 39.3% of Therapists reported receiving preventive care information by attending NSW Health oral health conferences.

| Item | Metropolitan | Rural and Remote | P-Value | TOTAL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enablers | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |

| 1.Engaging with adolescents attending the clinic is easy for me. | 45 | 4.27 | 0.78 | 71 | 4.27 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 116 | 1.27 | 0.88 |

| 2. My training and education has given me confidence to work effectively with adolescents | 42 | 4.26 | 0.8 | 72 | 3.89 | 1.13 | 0.2 | 115 | 3.99 | 1.1 |

| 3. I have confidence providing dietary advice for adolescents. | 45 | 4.36 | 0.83 | 72 | 4.21 | 0.87 | 0.37 | 117 | 4.27 | 0.85 |

| Constraints | ||||||||||

| 4. My knowledge of evidence- based preventive care for adolescents is inadequate | 45 | 2.4 | 1.12 | 72 | 2.61 | 1.06 | 0.33 | 117 | 2.53 | 1.08 |

| 5. I am not confident to communicate effectively with adolescents. | 43 | 1.86 | 0.91 | 71 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.83 | 114 | 1.89 | 0.97 |

| 6. I do not have time to reflect on my clinical practice | 44 | 2.32 | 1.12 | 72 | 2.61 | 1.07 | 0.16 | 116 | 2.5 | 1.09 |

Legend: strongly disagree = 1; disagree = 2; unsure = 3; agree = 4; strongly agree = 5

Table 1: Therapists ranking of enablers and constraints to offering preventive oral health care to adolescents.

Table 2 illustrates Therapists rating of statements pertaining to enablers and constraints to provide clinical preventive care to adolescents. Using an independent sample T-test, the means were compared for rural and metropolitan Therapists, and there were no significance difference between the responses for any of the questions asked. Respondents indicated that their training and education gave them the confidence to work effectively with adolescents (Mean 3.99; SD 1.10); the majority responded that they have sufficient knowledge of evidence based preventive care for adolescents (Mean: 2.53; SD 1.08); but complained of a lack of sufficient time to reflect on their clinical practice (Mean: 2.50; SD 1.09).

| Metropolitan | Rural | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Item | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD |

| 1 | Implement 6 monthly clinical peer reviews | 44 | 7.43 | 2.84 | 70 | 6.97 | 3.12 | 114 | 7.15 | 3.01 |

| 2 | Regular team building events to maintain morale and encourage ‘sharing of information’ to improve working partnerships | 44 | 5.61 | 2.84 | 70 | 5.46 | 2.85 | 114 | 5.52 | 2.84 |

| 3 | Referral system for focussed ‘prevention session’with dental/oral health therapist | 44 | 5.11 | 2.71 | 70 | 5.11 | 2.66 | 114 | 5.11 | 2.67 |

| 4 | ISOH tagged clinical preventive care appointment times for clinicians | 44 | 5.36 | 3.31 | 70 | 4.83 | 3.10 | 114 | 5.04 | 3.18 |

| 5 | Process to access oral health products consistently across the Local Health District for adolescents | 44 | 5.25 | 2.85 | 70 | 4.54 | 2.92 | 114 | 4.82 | 2.9 |

| 6 | Forum for clinicians to discuss different case studies, oral health information and education | 44 | 4.70 | 2.19 | 70 | 4.36 | 2.44 | 114 | 4.49 | 2.35 |

| 7 | Make resources available for interactive oral health education at the chair side e.g. development of age appropriate oral health education resources such as smart phone applications and DVD’s | 44 | 4.52 | 2.70 | 70 | 4.43 | 2.61 | 114 | 4.47 | 2.63 |

| 8 | Clinical team leaders to provide ongoing CE on evidence based practice and minimal intervention | 44 | 4.52 | 3.10 | 70 | 4.41 | 2.84 | 114 | 4.46 | 2.93 |

| 9 | Work culture change towards evidence-based practice | 44 | 3.77 | 2.98 | 70 | 3.77 | 3.14 | 114 | 3.77 | 3.07 |

| 10 | Preventive guidelines for adolescents in surgeries for clinicians | 44 | 3.82 | 2.79 | 70 | 3.43 | 2.64 | 114 | 3.58 | 2.69 |

Overall rank according to mean responses.

Table 2: Therapists response to the question “What in your opinion are the most important structures that need to be in place to support provision of preventive care in your clinic? (Please rank them: 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 and 10, with 1 as highly important)”.

When Therapists were asked to rank ten items that they viewed as important to support the provision of preventive oral health care for adolescents, the overall ranking is shown in Table 2 and the top five statements were:

(i). Implement 6 monthly clinical peer reviews.

(ii). Regular team building events to maintain morale and share information to improve working partnerships.

(iii). Referral system for focussed prevention session with dental/ oral health therapist.

(iv). Information System for Oral Health (ISOH) clinical preventive care appointment times for clinicians.

(v). Process to access oral health products consistently across the Local Health Districts, to support their patient’s homecare oral health practices.

When Therapists were asked who would be responsible to action their recommendations, 86 per cent stated clinical directors, 25 per cent recorded health service managers, and 52 per cent suggested oral health promotion coordinators and senior Therapists.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to scope continuing professional development in relation to the clinical preventive care of adolescents by Therapists. Overall, only 35 per cent received over 10 hours of CPD specifically focussed on preventive care for adolescents. Of concern is that approximately 20 per cent recorded not having any CPD on preventive care for adolescents. Many researchers [2,24-27] have urged dental practitioners to focus on the preventive care for adolescents as long term oral health outcomes will be improved by offering contemporary scientific evidence-based advice on preventive care and advice to all patients, particularly the disadvantaged groups seeking care in the public oral health settings.

Considering Grol’s [9] stance for improving patient care is to be informed by scientific literature, it may be that respondents did not undertake active CPD per se for preventive care, but, used self-directed learning by reading journal articles or on-line learning activities. Buck and Newton’s study [28] found that 87 per cent of dentists read professional journals more than once a month and 10.9 per cent less than once a month, however Barnes et al. [29] review stated it was acceptable as long as the reader was adept at filtering the information.

This study found 39.3 per cent of respondents used on-line websites to access relevant information; however, Hopcraft et al. [13] reported that Victorian dental practitioners did not rate the internet as a preferred format for CPD. Reynolds et al. [6] discussed the benefits of information communication technology (ICT) and e-learning where ‘students’ have the flexibility of learning at their own pace and in their own time and space. The authors alluded to ‘blended learning’ whereby a combination of face-to-face, simulations and on-line teaching may take place; suggesting major opportunities for Therapists in different settings to participate in clinical preventive care CPD offered via different modes of delivery. There is opportunity for further research, investigating the barriers for Therapists to access paediatric dental specialists to consult on specific clinical cases, as highlighted by LHDs clinical directors and health service manager’s vision to create learning environments among oral health professionals for patient care quality assurance [30].

Eaton and Reynold’s paper [31] discussed and illustrated innovative approaches on how ICT could be maximized in clinical settings, suggesting possibilities for interprofessional learning among dental practitioners in NSW LHDs. However, researchers have raised educational learning concerns associated with on-line learning such as participants’ information technology skills in navigating computer systems, methodology and limitations to clinical learning [29].

Overall, this study found Therapists (87.9%) received most of their preventive care CPD from within the LHDs in which they worked. Furthermore, a fair number of respondents (35.9%) reported receiving preventive care information from their clinical directors. The review by Barnes et al. [29] of CPD for dentists in Europe reported costs, health professional’s work and home, and financial commitments as factors influencing dentists’ participation in CPD. It would therefore appear logical for clinical directors and health service managers to invest and support CPD events for interprofessional education and learning within their LHDs for overall cost efficiency benefits. Bullock et al. [17] discussion paper refers to group learning, and hands on courses being popular with practical tips and information on new materials. The authors [17] stated that: ‘dentists are practical people who want practical courses’. A study assessing the factors influencing healthcare leaders to enhance Therapists’ offer of preventive care to adolescents, reported that creating learning environments for Therapists across the LHD oral health professional teams was a key strategy [30].

Therapists in this study reported that it was important to engage in 6 monthly peer reviews as a strategy to enhance their ability to provide preventive care to adolescents. Bullock et al. [17] discussed the value of collaborative clinical audit and peer review to identify the needs of dental practitioners and alluded to such benefits as providing a framework for clinical facilitators to plan focused local short courses for small groups. The authors stated that clinical audits and peer reviews are fundamental processes that could be used to develop more comprehensive structured CPD, and could be linked to an assessment of their impact on practice.

A recent paper [29] reported that peer review and self-assessment are recommended components for CPD to identify areas for improvement, encompassing self-reflection as a key factor in potentially changing clinical practice. Interestingly, this study found that respondents reported that there was a lack of time to reflect on their clinical practice, indicating an area for further investigation.

Although there appears to be little information available for oral health practitioners learning in workplaces, Simpson and Freeman’s [32] paper on reflective practice and experiential learning tools for continuing professional development provided information for oral health teams and health managers to implement performance appraisals which should include strategies to enhance health professional’s workplace health and patient safety.

The findings from this study suggest there are opportunities for NSW LHD clinical directors, as health care leaders, to provide focused clinical preventive care advice for Therapists, with interprofessional educational learning opportunities using evidence-based quality improvement and clinical governance mechanisms [33,34].

Caution in the interpretation of the findings for generalised use should be exercised, as the results demonstrated no significant tendencies towards enablers or constraints to the statements posed, or significant variations towards which structures or processes were more effective than others to support Therapists to provide preventive care for adolescents. However, as reported in this study, it may be due to the lack of time for clinicians to reflect on their clinical practices.

Conclusion

This study has shown that continuing professional development opportunities should be explored for Therapists to receive education within their Local Districts provided by visiting dental specialists, clinical directors, senior staff dentists and supported by health managers.

This study has shown that one third of Therapists had received less than 5 hours CPD in the last 2 years on helping adolescents maintain their oral health. In order to support Therapists continuing professional education, interprofessional peer reviews in partnership with dentists, visiting dental specialists, and whole team approaches should be implemented within all LHD’s. In addition, the scoping of other modes of education such as the Information Communication Technology are worthy of further investigation.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: NSW Ministry of Health Rural and Remote Allied Health Professionals Postgraduate Scholarship Scheme and Centre for Oral Health Strategy.

Special thanks to Francis Baker, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Newcastle for her professional statistics guidance. We are grateful to the Australian Capital Territory Therapists for piloting the survey questionnaire, and to all NSW Local Health Districts Therapists who generously gave of their time to complete and return the survey.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The findings from this study are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the funding agency or NSW Ministry of Health.

References

- Ismail AI, Sohn W, Tellez M, Willem JM, Betz J, et al. (2008) Risk indicators for dental caries using the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 36: 55-68.

- Tickle M, Milsom KM, King D, Blinkhorn AS (2003) The influences on preventive care provided to children who frequently attend the UK General Dental Service. Br Dent J 194: 329-332.

- Grol R (2001) Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care 39: 46-54.

- Davies RM, Blinkhorn AS (2013) Preventing Dental Caries: Part 1 the scientific rationale for preventive advice. Dent Update 40: 719-720, 722, 724-726.

- Brown CA, Belfield CR, Field SJ (2002) Cost effectiveness of continuing professional development in health care: a critical review of the evidence. BMJ 324: 652-655.

- Reynolds PA, Mason R, Eaton KA (2008) Remember the days in the old school yard: From lectures to online learning. Br Dent J 204: 447-451.

- Dental Board of Australia: Continuing professional development registration standard.

- (2013) General Dental Council: Continuing professional development for dental professionals. General Dental Council, UK.

- Grol R, Grimshaw J (2003) From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet 362: 1225-1230.

- Cheater F, Baker R, Gillies C, Hearnshaw H, Flottorp S, et al. (2009) Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

- Eaton KA, Reynolds PA (2008) Continuing professional development and ICT: Target practice. Br Dent J 205: 89-93.

- Best HA, Messer LB (2003) Effectiveness of interventions to promote continuing professional development for dentists. Eur J Dent Educ 7: 147-153.

- Hopcraft MS, Marks G, Manton DJ (2008) Participation in continuing professional development by Victorian dental practitioners in 2004. Aust Dent J 53: 133-139.

- (2013) NSW Ministry of Health: Oral health 2020: A strategic framework for dental health in NSW. Sydney: NSW Health.

- (2014) NSW Ministry of Health: NSW state health plan towards 2012. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health.

- Redwoo d C, Winning T, Townsend G (2010) The missing link: self-assessment and continuing professional development. Aust Dent J 55: 15-19.

- Bullock AD, Butterfield S, Belfield CR, Morris ZS, Ribbins PM, et al. (2000) A role for clinical audit and peer review in the identification of continuing professional development needs for general dental practitioners: a discussion. Br Dent J 189: 445-448.

- Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW (2013) Pit and fissure sealants: Use of in oral health services, NSW.

- (2009) Centre for Oral Health Strategy and Smoking cessation. Department of Health NSW, Australia.

- Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW (2006) Fluorides - Use of in NSW. Edited by Ministry of Health Sydney.

- Masoe AV, Blinkhom AS, Taylor J, Blinkhorn FA (2014) Factors influencing provision of preventive oral health care to adolescents attending public oral health services in New South Wales, Australia. J Dent Oral Health 2:1-8.

- Oppenheim AN (2005) Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement. New Edition. London: Continuum.

- (2012) IBM SPSS Statistics. New York: IBM Corp.

- Lee JY, Divaris K (2014) The ethical imperative of addressing oral health disparities: A unifying framework. Journal of Dental Research 93:224-230.

- Moynihan PJ, Kelly Sam (2014) Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: Systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J Dent Res 93:8-18.

- Waterhouse PJ, Auad SM, Nunn JH, Steen IN, Moynihan PJ (2008) Diet and dental erosion in young people in south-east Brazil. Int J Paediatr Dent 18: 353-360.

- (2005) American academy of pediatric dentistry council on clinical affairs; American academy of pediatric dentistry committee on the adolescent. Guideline on adolescent oral health care. Pediatr Dent 27: 72-79.

- Buck D, Newton T (2002) Continuing professional development amongst dental practitioners in the United Kingdom: How far are we from lifelong learning targets? Eur J Dent Educ 6: 36-39.

- Barnes E, Bullock AD, Bailey SE, Cowpe JG, Karaharju-Suvanto T (2013) A review of continuing professional development for dentists in Europe(*). Eur J Dent Educ 17 Suppl 1: 5-17.

- Masoe AV, Blinkhorn AS, Taylor J, Blinkhorn FA (2015) Assessment of the management factors that influence the development of preventive care in the New South Wales public dental service. Journal of Healthcare Leadership 7:1-11.

- Eaton KA, Reynolds PA (2008) Continuing professional development and ICT: Target practice. Br Dent J 205: 89-93.

- Simpson K, Freeman R (2004) Reflective practice and experiential learning: Tools for continuing professional development. Dent Update 31: 281-284.

- Brocklehurst P, Ferguson J, Taylor N, Tickle M (2013) What is clinical leadership and why might it be important in dentistry? Br Dent J 214: 243-246.

- Campbell S, Tickle M (2013) How do we improve quality in primary dental care? Br Dent J 215: 239-243.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14474

- [From(publication date):

August-2015 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9934

- PDF downloads : 4540