Management of Acute Bleeding Post Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

Received: 04-Dec-2017 / Accepted Date: 11-Dec-2017 / Published Date: 25-Dec-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2165-7904.1000359

Abstract

Introduction: Bariatric procedures are widely spreading nowadays, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is one of the most commonly performed Bariatric operations, post-operative bleeding is being a serious and a common event of this operation.

Materials and methods: A retrospective analysis was performed for 80 out of 1500 patients, who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in the period between March 2015 and August 2017. The rate of hemorrhagic complications was 5.3%, the mean age was 38.5 (± 8.718349), and the mean BMI was 40 (± 3.780856)

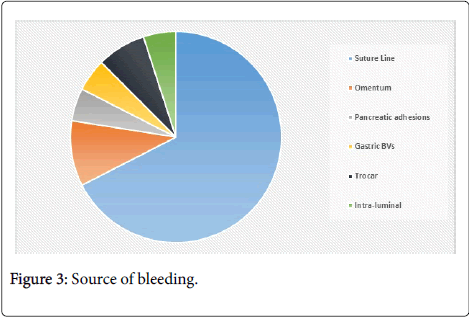

Results: Source of bleeding was mostly intra-abdominal of which 95% of 76 patients, while intra-luminal bleeding represented only 5% of 4 patients. While in the intra-abdominal bleeding, 54 were there which had bleeding from the staple line, in 8 cases the bleeding was from the omentum, while 4 bled from the gastro-pancreatic adhesions, 4 bled from short gastric vessels, and in 6 patients the bleeding was from the trocar entry site.

Conclusion: Early re-laparoscopy after post-LSG bleeding is diagnostic and therapeutic, and decreases both morbidity and mortality of patients.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery; Diabetes therapy; Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; Mini gastric bypass

Introduction

Postsurgical complications after sleeve gastrectomy can be divided into early and delayed. Hemorrhage is considered to be one of the most common early complications after sleeve gastrectomy [1]. Possible causes include lengthy staple line and the change in intra-gastric pressure. Another important risk factor for increased postoperative bleeding is preoperative low molecular weight heparins used for prevention of venous thromboembolism [2-4]. Chronic bleeding in LSG however is very uncommon and related to ulcers that may develop within the remnant stomach. Incidence of hemorrhage post LSG has been reported in 1.1–8.7% of cases [5]. Postoperative bleeding can be classified based on bleeding site into intra-luminal bleeding (ILB) into the gastrointestinal tract or intra-abdominal bleeding (IAB) into the abdominal cavity [6-8].Intraluminal bleeding from the staple line usually presents with an upper gastrointestinal bleed as hematemesis or later on melena stools, in addition to tachycardia and hypotension. Management of intraluminal bleeding was conservative [9]. Intra-abdominal hemorrhage presents in the abdominal cavity and early indication of intra-abdominal bleeding will be through the abdominal drain [10]. Intra-abdominal bleeding usually presents with a serial drop in serum hemoglobin levels and/or signs of tachycardia or hypotension. Common sources for intra-abdominal bleeding include the gastric staple line, spleen, liver or abdominal wall at the sites of trocar entry [9,11]. An increased risk of hematoma developing and abscess formation is found as a result. Early bleeding through drains or NG tube is called a sentinel bleed and it usually can occur within hours of surgery [12-15].

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of 1500 morbidly obese patients who were collected from General Surgery Department at Ain Shams university hospitals (El-Demerdash hospital) [16].The patients underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in the period between march 2015 till August 2017. An aggregate of 80 patients out of the 1500 presented by post LSG bleeding within the first 6 hours. According to the clinical presentation , bleeding was classified into 2 groups: Group I: Intra-abdominal: this comprised 76 patients out of the 80. They presented with tachycardia (>100 b/m), hypotension (<90/60 mmHg), increase in the drainage volume (>100 cc/hr), and abdominal pain [17,18]. While 6 out of the 38 patients bled from the trocar insertion site. Group II: Intra-luminal bleeding: 4 patients out of the 80 patients presented with hematemesis and melena in addition to tachycardia and hypotension.

In these cases we initiated fluid resuscitation, performed laboratory tests (CBC and coagulation profile) and also pelvi-abdominal ultrasound examination if feasible [19]. Patients with poor response to fluid resuscitation were returned to operating room (OR) for urgent Re-laparoscopy to identify the source of bleeding.

Management

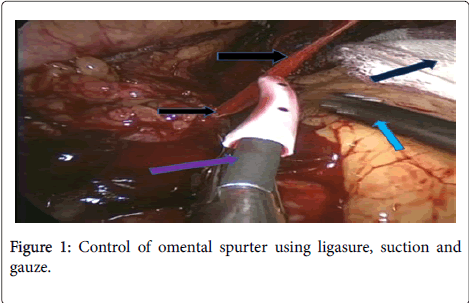

Whereas 36 patients underwent urgent Re-laparoscopy to identify the source of bleeding. Diagnostic laparoscopy is considered to be an excellent option to allow direct visualization and to identify the bleeding source [8]. It also allows evacuation of the hematoma and a thorough washout to prevent formation of an abscess (Figure 1).

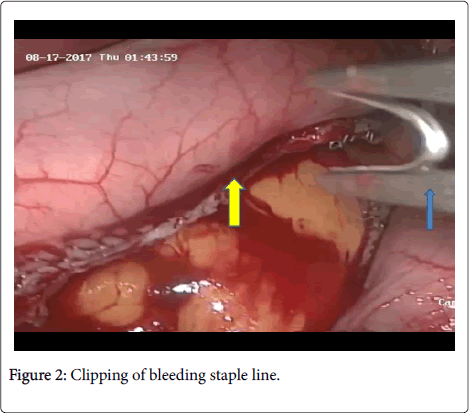

After insertion of ports, thorough and meticulous exploration was done after evacuation of the hematoma. Intra-operative packing to help control bleeding and allow hemostasis. Packing can be done with inserting gauze to help to identify the bleeding source [20,21]. Suction and irrigation can also help us to identify the source of bleeding and allow for the application of a clip, cauterizing the bleeding points, or application of under-running sutures (Figure 2).

Results

Independent demographic variables were sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and co-morbidities (Table 1)

| Independent Variable | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 30 | 37.5 |

| Female | 50 | 62.5 |

| Total | 80 | 100 |

Table 1: Independent variables according to gender.

This table shows that most of the patient were females as they represented 62.5%, while the male patients only 37.5% (Table 2).

| Independent Variables | Number | Range | Mean | ±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 80 | 24 – 55 | 38.5 years | 8.718349 |

| B.M.I. | 80 | 35 – 45 | 40 kg/m2 | 3.780856 |

Table 2: Independent Variables according to age and BMI.

The table shows that the mean age was 38.5 years (± 8.718349), while the mean BMI was 40 kg/m2 (± 3.780856). A total of 36 patients underwent urgent re-laparoscopy to identify the source of bleeding (Table 3 and Figure 3).

| Parameters | Number | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of bleeding (80) |

Intra-abdominal | Suture line | 54 | 67.5 |

| Omentum | 8 | 10 | ||

| Pancreatic adhesion | 4 | 5 | ||

| Gastric Blood vessels | 4 | 5 | ||

| Trocar Insertion site | 6 | 7.5 | ||

| Intra-luminal | 4 | 5 | ||

Table 3: Source of Bleeding.

• 54 cases bled from the suture line.

• 8 cases bled from the omentum (gastrocolic ligament).

• 4 cases bled from gastro-pancreatic adhesions.

• 4 cases bled from short gastric (upper polar) vessels.

• 6 patients had bleeding from the trocar site bleeding (to exclude other sources of bleeding).

Group I:

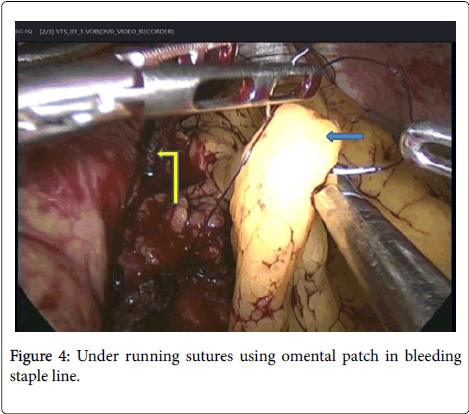

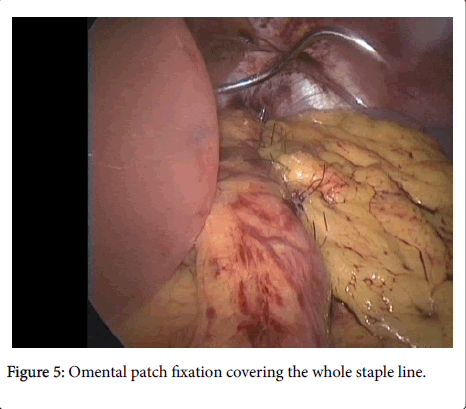

• Bleeding from suture line was managed by: under running sutures to all 54 patients, 14 patients with omental fixation as a patch, and 40 patients without omental fixation. Some clips application was needed.

• Bleeding from omentum was managed by cauterization and clipping of bleeding points and ligation of right gastro-epiploic vessels below the pylorus.

• Bleeding from gastro-pancreatic adhesions was managed by ligation and clipping of the bleeders.

• Bleeding from short gastric (upper polar) vessels was managed by ligation and clipping of the vessels.

• Bleeding from port site: 4 patients were managed conservatively by compression (using Elasto-plast) and 2 patient needed relaparoscopy to exclude other causes of bleeding, and the bleeding was controlled by widening of port site and cauterizing the bleeder (Figures 4 and 5).

Group II:

Patients usually bled from staple line, and they were managed conservatively using:

• Fluid resuscitation.

• Follley’s catheter insertion to monitor urine output.

• Blood transfusion.

• Follow-up of hemoglobin and hematocrite.

Discussion

Post-operative bleeding is certainly the most common and early complication. Usually it occurs during the first or second postoperative day. It was found that the most common and major early complication is certainly the post-operative bleeding, which can occur in up to 16% of patients, with reported average of 3.6% [22]. We found that our early intervention has decreased the hospital stay, decreased the risk of infection, decreased risk of blood transfusion, and speeded up the patient recovery and normal lifestyle comeback.

The age range was between 24-55 years with mean 41.2, this was agreed by Michael who found the same mean age. Our results also found that the female gender was more than the male gender, and that mean BMI>41 kg/m2 where it was 47.3 kg/m2.

In our study 80 patients out of the 1500 presented by post LSG acute bleeding within the first 6 hours. It was found that the postsurgical complications after sleeve gastrectomy can be divided into acute and chronic [23]. It was found that acute or early post-operative bleeding usually occur within 12-48 hours after surgical procedure [1]. It was showed that late and chronic bleeding will usually present more than 42 days after the procedure [9,17].

Conclusion

Early re-laparoscopy after post-LSG bleeding is diagnostic and therapeutic, and decreases both morbidity and mortality of patients.

Conflict of Interest

No any type of conflict of interest or financial support.

Ethical Approval

An approval from all participants in the study was obtained.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Fridman A, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ (2015) Postoperative bleeding in the bariatric surgery patient. 21: 241-247.

- Aggarwal S, Sharma AP, Ramaswamy N (2013) Outcome of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with and without staple line oversewing in morbidly obese patients: A randomized study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 23: 895–899.

- Baker RS, Foote J, Kemmeter P, Brady R, Vroegop T, et al. (2004) The science of stapling and leaks. Obes Surg 14: 1290–1298.

- Buchwald H, Oien D (2013) Metabolic/Bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 23: 427-436.

- Cuesta MA, Bonjer HJ (2014) Treatment of postoperative complications after digestive surgery. London: Springer London.

- Ugo DS, Gentileschi P, Benavoli D, Cerci M, Gaspari A, et al. (2014) Comparative use of different techniques for leak and bleeding prevention during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a multicenter study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 10: 450–454.

- Dapri G, Cadiere GB, Himpens J (2010) Reinforcing the staple line during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: Prospective randomized clinical study comparing three different techniques. Obes Surg 20: 462–467.

- Frezza EE (2007) Laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. The future procedure of choice? Surg Today 37: 275–281.

- Gill RS, Whitlock KA, Mohamed R, Sarkhoush K, Birch DW, et al. (2012) The role of upper endoscopy in treating postoperative complications in bariatric surgery. J Interv Gastroenterol. 2: 37–41.

- Katzmarzyk PT, Mason C (2006) Prevelance of class I, II and III obesity in Canada. CMAJ 174: 156–157.

- Kehagias I, Zygomalas A, Karavias D, Karamanakos S (2016) Sleeve gastrectomy: Have we finally found the holy grail of bariatric surgery? A review of the literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 20: 4930-4942.

- Kourosh S, Birch DW, Sharma A, Karmali S (2015) Complications associated with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: A surgeon’s guide. Can J Surg 56: 347-352.

- Melissas J, Koukouraki S, Askoxylakis J, Stathaki M, Daskalakis M, et al. (2007) Sleeve gastrectomy: A restrictive procedure? Obes Surg 17: 57–62.

- Janik MR, Waledziak M, BrÄ…goszewski J, Kwiatkowski A, Pasnik K (2016) Prediction model for hemorrhagic complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: Development of SLEEVE BLEED calculator. Obesity Surg 27: 968-972.

- Mittermair R, Sucher R, Perathoner A (2014) Results and complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Today 44: 1307–1312.

- Han MS, Kim WW, Oh JH (2005) Results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) at 1 year in morbidly obese Korean patients. Obes Surg 15: 1469–1475.

- Nguyen NT, Langoria M, Chalifoux S, Wilson SE (2004) Gastrointestinal bleeding after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg 14: 1308–1312

- Regan JP, Inabnet WB, Gagner M, Pomp A (2003) Early experience with two-stage laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as an alternative in the super-super obese patient. Obes Surg 13: 861–864.

- Ren CJ, Patterson E, Gagner M (2000) Early results of laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch: A case series of 40 consecutive patients. Obes Surg 10: 514–523.

- Shikora SA, Mahoney CB (2015) Clinical benefit of gastric staple line reinforcement (SLR) in gastrointestinal surgery: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg 25: 1133–1141.

- Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Guarino S, Cirocchi R, Scalercio V, et al. (2013) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared with other bariatric surgical procedures: A systematic review of randomized trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis 9: 816-829.

- Amirthalingam A, Rao J, Rachel Maria Gomes (2017) Prevention and management of bleeding after sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass. Bar Surg Pract Guide 10: 239-246.

- Zeni T, Rn ST, Roberts J (2015) Bleeding rates are increased with preoperative lovenox administration in patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 11: S17.

Citation: Sabry K, Hamed A, Habib H, Helmy M, Abouzeid T (2017) Management of Acute Bleeding Post Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. J Obes Weight Loss Ther 7: 359. DOI: 10.4172/2165-7904.1000359

Copyright: © 2017 Sabry K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 9681

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Jul 11, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 8891

- PDF downloads: 790