Research Article Open Access

Low Birth Weight and Prematurity in Teenage Mothers in Rural Areas of Burkina Faso

Biébo Bihoun1,2*, Serge Henri Zango2, Maminata Traoré-Coulibaly2, Toussaint Rouamba2, Daniel Zemba3, Marc-Christian Tahita2, Sibiri Yarga2, Benjamin Kabore2, Palpouguini Lompo2, Innocent Valea2, Sékou Ouindpanga Samadoulougou1, Raffaella Ravinetto4, Jean-Pierre Van-Geertruyden5, Umberto D’Alessandro6,7, Halidou Tinto2 and Annie Robert21UCL-IREC-EPID, Epidemiology and Biostatistics Research Division, Belgium

2IRSS-Clinical Research Unit of Nanoro, Burkina Faso

3Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Yalgado Ouédraogo, Burkina Faso

4Public Health Department, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium

5Global Health Institute, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

6Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia

7London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK

- Corresponding Author:

- Biébo Bihoun

UCL-IREC-EPID

Epidemiology and Biostatistics Research Division

Brussels, Belgium

Tel: +32465319545

Fax: +3227643322

E-mail: biebo.bihoun@uclouvain.be

Received date: July 13, 2017; Accepted date: August 24, 2017; Published date: August 31, 2017

Citation: Bihoun B, Zango SH, Traoré-Coulibaly M, Rouamba T, Zemba D, et al. (2017) Low Birth Weight and Prematurity in Teenage Mothers in Rural Areas of Burkina Faso. J Preg Child Health 4:344. doi:10.4172/2376-127X.1000344

Copyright: © 2017 Bihoun B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health

Abstract

Background: Adolescence is associated with adverse fetal outcome, particularly in resources limited settings. We assessed the association between mother’s age and low birth weight or prematurity in Nanoro, a rural health district of Burkina Faso. Methods: We collected data on mothers and their newborns in the framework of the “Safe and Efficacious Artemisinin-based Combination Treatments for African Pregnant Women with Malaria” clinical trial. Low birth weight or prematurity was defined as adverse fetal outcome. Logistic regression was used to compare its occurrence in teenagers and in women aged ≥ 20 years. Results: From June 2010 to November 2013, 870 pregnant women enrolled in the PREGACT study were treated for a Plasmodium falciparum infection and followed up until delivery. Of the 823 women with singleton live-borns, 205 (24.9%) were teenagers of whom 44 (5.3%) were minors (15-17 years). Up to 91.7% of adolescents presented with anemia at entry. The incidence of adverse fetal outcome in teenagers was 39.8%, increasing to 50.0% in minors. Anemic adolescents were significantly at higher risk of delivering low birth weight or preterm babies compared to their older counterparts. In multivariate analysis, teenagers with both anemia and fever presented the highest and significant odds ratios of adverse fetal outcome, whatever was their BMI: Teenagers with anemia, fever and high BMI at entry, AOR=3.46, 95% CI: (1.40, 8.58), teenagers with anemia, fever and low BMI at entry, AOR=2.86, 95% CI: (1.14, 7.13). Conclusion: Teenager’s pregnancy is associated with adverse fetal outcome in the rural health district of Nanoro, mainly when teenagers experiment anemia and fever. In low resources setting, multidisciplinary approach including education and setting up favorable socio-economic environment are needed to prevent early motherhood.

Keywords

Teenagers; Low birth weight; Preterm birth; Rural; Burkina Faso

Introduction

In 2010, 36.4 million women aged 20-24 years had given birth to a live child before their 18th birthday. This was much more common in West and Central Africa (28%) than in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (4%). Similar proportions were found for giving birth before the 15th birthday, i.e. 6% and 0.2%, respectively. In Burkina Faso, the prevalence of a first birth before 18 was estimated at 28% [1].

Teenage pregnancy is a concern worldwide as it is associated with low birth weight (LBW) and preterm birth (PTB) [2-4]. Pregnancy in teenagers can result in adverse maternal outcome such as severe anemia or death and compromise their socio-economic opportunities [5]. Children from teenage mothers are more likely to be stunted at their second birthday, to develop glucose disorder and problems at school [3]. They are more often hospitalized and will contribute with more than half to the following generation of adolescent mothers [6]. Moreover, PTB complications are one of the main causes of death among children aged less than 5 years [7]. LBW has also been associated to an increased neonatal mortality and hospitalization [8,9]. Premature infant’s experience also more temperature instability, hypoglycemia, respiratory distress and jaundice [10]. Later in life they are more likely to present impaired neurodevelopment, impaired learning capacity, and impaired behavior. Previous studies that reported an association of LBW or PTB with maternal age remains controversial about mechanisms involved [8,11-13].

Studies focusing on adverse fetal outcome in adolescents are scarce in Burkina Faso, despite a high proportion of them that could further increase in the upcoming decades [1]. This study aimed at assessing the prevalence of adolescents’ pregnancy in Burkina Faso and its association with LBW or PTB in the rural setting of Nanoro and Nazoanga.

Materials and Methods

Study settings

This study was nested in the PREGACT multicenter clinical trial (trial registration NCT00852423). Details of the methodology and results have been reported elsewhere [14]. The study was designed to assess the efficacy and the safety of four artemisinin based combinations treatments against malaria in pregnancy. Seven sites in four countries were involved of whom two in Burkina Faso. The present analysis uses data collected from all pregnant women enrolled in Burkina Faso.

Recruitment

Pregnant women attending the antenatal care clinic in Nanoro or Nazoanga were screened for malaria using a rapid diagnostic test. If positive, study protocol and procedures were explained and a written informed consent obtained. Women included in the trial were those residing within the health center catchment zone, aged of at least 15 years, with a pregnancy between 16 and 37 weeks, with Plasmodium falciparum infection, a hemoglobin level of at least 7 g/dL, willing to deliver at the health facility, and to adhere to the study required procedures. They should be able to provide written informed consent also. Exclusion criteria were history of illness which may affect pregnancy outcome, history of allergy to the study drugs, history of known obstetric complication or bad pregnancy history, current use of cotrimoxazole or antiretroviral treatment, evidence of intake of antimalarial drug or antimicrobials with antimalarial activity, inability to take oral treatment, or requirement of hospitalization because of serious illness at screening. Women intending to leave the study catchment area prior to delivery and those currently participating to another study were also excluded. In Burkina Faso, women were randomized to one of the three following treatments: Artesunate-Amodiaquine (ASAQ), Arthemether-Lumefantrine (AL) and Mefloquine-Artesunate (MQAS). Randomization was done using balanced incomplete block design. Participants were treated and observed the first three days by study nurses.

At recruitment study staff recorded demographics, anthropometrics, medical and pregnancy history. A portable ultrasonography device allowed assessment of the fetal viability.

Follow-up

Visits were scheduled over 9 weeks after treatment, at days 3, 7 and then once a week. Subsequently, women were encouraged to attend the antenatal clinic monthly until delivery and at any time they felt unwell, regardless to the schedule.

At each scheduled and unscheduled visit, physical examination was performed. Weight, height and temperature were measured. Signs and symptoms since last visit were collected. A blood sample was taken for malaria smears while hematology was done on days 7, 14, 28 and 63 and biochemistry at days 7 and 14 only.

Recurrent malaria infection was treated as per the malaria national program guidelines. After delivery, the newborn was weighted within 72 h. The gestational age was determined using the Ballard score [15].

Laboratory methods

Thin and thick blood smears were obtained from each participant to determine parasite density. A portable HemoCue device (Hb301 Hemocue®, Angelholm, Sweden) was used to determined maternal hemoglobin level. Detail laboratory methods have been published elsewhere [14,16].

Ethics

The PREGACT study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Antwerp, Belgium, the Institutional Ethics committee of Centre Muraz and the Ethics committee of the Ministry of Health, Burkina Faso [16]. All data were coded, and no participant’s identifiers appeared either in the study case report form, database and previous publications. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants and, for those minor of age, from their representatives

Definitions and statistical analysis

Maternal age was determined at entry from the date of birth in the health booklet or self-reported by the participant. Teenager was defined as an individual between the age of 15 and 19 years according to the WHO definition [17]. Teenagers were divided in two subgroups: 15-17 and 18-19 years old.

The dependent variable was adverse fetal outcome defined as the occurrence of LBW (<2500 g) and/or PTB (gestational age<37 weeks). The weight was measured within 72 h after birth using digital scales and Ballard score was assessed at birth by the study physician [15].

Baseline pregnancy BMI (weight in kg divided by square of height in m), fever (body temperature ≥ 37.5°C) and anemia (hemoglobin level<11 g/dl) were covariates analyzed along with maternal age.

As part of the PREGACT quality assurance system, all data were entered into an electronic case report form built under MACRO software (InferMed, Kings Clinical Trial Unit, and King’s College London, UK). They were checked for consistency and all queries were resolved before locking the database for statistical analysis.

Univariate logistic regression was used to assess whether teenagers had a higher adverse pregnancy outcome than adults at each level of the covariates. Adjustments were then made using a multivariate logistic regression. All covariates and their interaction terms with maternal age were included in the model independently of their statistical significance. The estimated coefficients including those of the interactions, their standard errors and their correlation coefficients were used to derive adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for each combination of the covariates.

A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered as a statistical significant result. All analyses were performed with STATA 14.1 IC® software (StataCorp LP, Texas USA).

Results

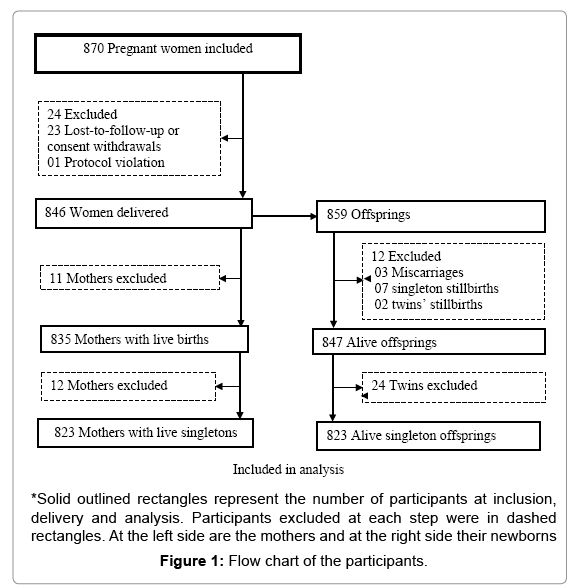

From June 2010 to November 2013, 870 pregnant women in their second or third trimester were enrolled in the trial and randomized to one of the three treatment groups. A total of 846 women delivered while 23 withdrew or were lost to follow-up. One woman was excluded by the investigator because of protocol violation (no malaria infection at inclusion). Among the 859 offspring, 847 were live births including 24 twins. Relationship with adverse fetal outcome was assessed on the 823 singleton live births and their mothers. A total of 14 newborns had missing data: 8 lack information on birth weight and 7 were not assessed for gestational age at birth. The large majority of women (73.0%, 601/823) were in their second trimester of pregnancy, there were 205 (24.9 %) teenagers, including 44 (5.3%) minors (15-17 years). More than a quarter 233 (28.3%) were primigravidae and up to 74.6% had anemia (Figure 1 and Table 1).

| Maternal age (years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N=823 |

Teenagers | Adults | |||

| 15-17 n=44 |

18-19 n=161 |

All teenagers n=205 |

20-45 n=618 |

||

| Recruitment site | |||||

| Nanoro | 552 | 33 (6.0) | 114 (20.7) | 147 (26.6) | 405 (73.4) |

| Nazoanga | 271 | 11 (4.1) | 47 (17.3) | 58 (21.4) | 213 (78.6) |

| Treatment arm | |||||

| ASAQ | 278 | 14 (5.0) | 65 (23.4) | 79 (28.4) | 199 (71.6) |

| AL | 277 | 13 (4.7) | 48 (17.3) | 61 (22.0) | 216 (78.0) |

| MQAS | 268 | 17 (6.3) | 48 (17.9) | 65 (24.3) | 203 (75.7) |

| Pregnancy trimester | |||||

| Second | 601 | 36 (6.0) | 125 (20.8) | 161 (26.8) | 440 (73.2) |

| Third | 222 | 8 (3.6) | 36 (16.2) | 44 (19.8) | 178 (80.2) |

*ASAQ: Artesunate-Amodiaquine; AL: Arthemether-Lumefantrine; MQAS: Mefloquine-Artesunate

Table 1: Recruitment and randomization characteristics by maternal age group.

Half (50.2 %) of the teenagers had a low BMI (≤ 21kg/m2), 18.5% had fever at entry. There was a significantly higher proportion of anemia in teenagers than in adults (91.7% versus 68.9 %, p-value<0.001). Among the 823 newborns, 113 (13.9%) were premature and 148 (18.1%) had a LBW (Table 2).

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N=823 | Teenagers | Adults | ||||

| 15-17 n=44 |

18-19 n=161 |

All teenagers n=205 |

20-45 n=618 |

p-value* | ||

| Pregnancy BMI | 0.70 | |||||

| 16-21 | 423 | 24 (54.5) | 79 (49.1) | 103 (50.2) | 320 (51.8) | |

| 21-30 | 400 | 20 (45.5) | 82 (50.9) | 102 (49.8) | 298 (48.2) | |

| Fever at inclusion | 0.12 | |||||

| Yes | 125 | 9 (20.5) | 29 (18.0) | 38 (18.5) | 87 (14.1) | |

| No | 698 | 35 (79.5) | 132 (82.0) | 167 (81.5) | 531 (85.9) | |

| Anemia at inclusion | <0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 614 | 41 (93.2) | 147 (91.3) | 188 (91.7) | 426 (68.9) | |

| No | 209 | 3 (6.8) | 14 (8.7) | 17 (8.3) | 192 (31.1) | |

*p-value is for all teenagers versus adults; BMI: Body Mass Index (kg/m2)

Table 2: Obstetrical and clinical characteristics of teenagers and adults pregnant women.

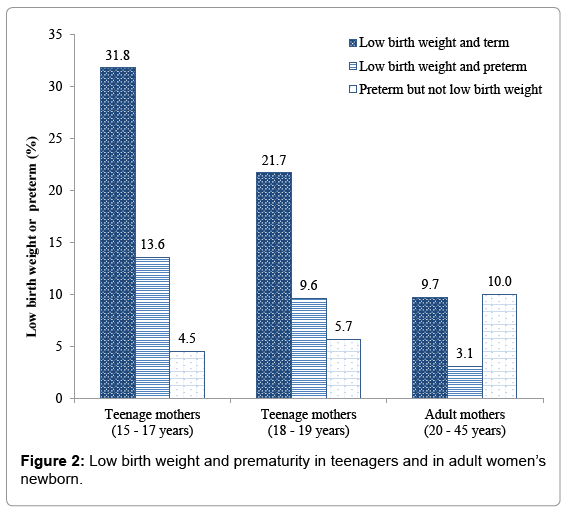

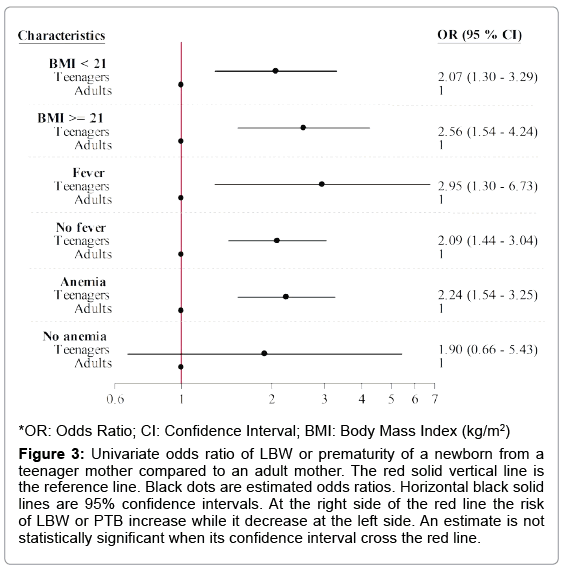

The overall incidence of adverse fetal outcome was 27.1%, increasing up to 39.8% among teenagers and up to 50.0% in minors (15- 17 years). In teenagers, most LBW infants were born from pregnancies at term, the highest incidence, 31.8%, being in minors. Teenagers were significantly at higher risk of delivering LBW or PTB babies compared to older women, regardless of their BMI (BMI of 16-21, OR=2.07, 95% CI: (1.30, 3.29), BMI of 21-30, OR=2.56, 95% CI: (1.54, 4.24)). Teenager’s babies had also an increased risk of LBW or PTB whatever was the temperature at entry. Newborns from anemic teenage mothers were at higher risk of adverse fetal outcome than those from anemic adults. (OR=2.24, 95% CI: (1.54, 3.25)) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 3: Univariate odds ratio of LBW or prematurity of a newborn from a teenager mother compared to an adult mother. The red solid vertical line is the reference line. Black dots are estimated odds ratios. Horizontal black solid lines are 95% confidence intervals. At the right side of the red line the risk of LBW or PTB increase while it decrease at the left side. An estimate is not statistically significant when its confidence interval cross the red line.

In multivariate analysis, teenagers with both anemia and fever presented the highest and significant odds ratios of delivering LBW or PTB babies, regardless of the BMI: Teenagers with anemia, fever and low BMI at entry, AOR=2.86, 95% CI: (1.14, 7.13), teenagers with anemia, fever and high BMI at entry, AOR=3.46, 95% CI: (1.40, 8.58) (Table 3).

| Adjustment covariates | AOR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | Fever | Anemia | |

| <21 | Yes | Yes | 2.86 (1.14-7.13) |

| <21 | Yes | No | 2.46 (0.62-9.76) |

| <21 | No | Yes | 1.97 (1.19-3.26) |

| <21 | No | No | 1.70 (0.54-5.29) |

| ≥ 21 | Yes | Yes | 3.46 (1.40-8.58) |

| ≥ 21 | Yes | No | 2.98 (0.79-11.24) |

| ≥ 21 | No | Yes | 2.39 (1.35-4.22) |

| ≥ 21 | No | No | 2.06 (0.68-6.26) |

*AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; BMI: Body Mass Index (kg/m2)

Table 3: Multivariate odds ratio of low birth weight or prematurity of a newborn from a teenage mother compared to an adult mother.

Discussion

The analyses nested in the main PREGACT trial offered the opportunity to investigate consequences of teenagers’ pregnancies on their offspring. In rural Burkina Faso, in Nanoro and Nazoanga, about a quarter of pregnant women in the study were teenagers. Adverse fetal outcomes, particularly LBW and PTB, were frequent among teenagers, regardless of the BMI. In addition, anemia and fever increased such a risk. Such level of childbearing by adolescents has been reported by studies done in other sub-Saharan countries: 21.1% in Zimbabwe, 24.4% in Cameroon and 24% in a multi-country study in sub-Saharan Africa [12,18,19]. This is also consistent with the distribution of teenage pregnancies in the world, the highest rates being recorded in the developing countries [1].

Some literature shows that teenager’s mothers share more unfavorable socio-economic characteristics than adults [11,20]. Most of the time they were unemployed or earned less income, live in rural areas, have low educational level and do not use effective contraceptive methods [20-23]. We did not assess the socio-economic background of our participants. Nevertheless, Burkina Faso like others West African countries is a low resources country where 67 % of the teenage girls aged 15-19 years live in rural areas. A large proportion of rural adolescents (83.3%) are out of school and only 3% use a modern contraceptive method [24]. A study conducted in inpatient neonates in Burkina Faso reported a higher rate (33%) of adolescent mothers [25]. This is in line with publications stating that newborns from adolescent mothers have a higher risk of hospitalization compared to those form non-adolescent mothers [6].

In our study teenagers LBW and PTB deliveries were 34.0% and 16.3%, respectively. In other sub Saharan countries the rates were lower, but not homogenous [2,12,19,21,26]. This maybe reflects behavioral and cultural diversity among pregnant adolescents across countries [27,28]. Higher proportions (LBW 38.9%, PTB 27.7%) were found in India [29]. We link this to the greater proportion (11%) of young teenagers (15-17 years) in this study, given that inverse relationship between maternal age and adverse fetal outcome [4,30,31].

In this study we did not aim at exploring factors associated with LBW or PTB. Our focus was on the potential risk of these adverse fetal outcome associated with the status of being a teenager.

In our univariate analysis adolescence was associated with LBW or PTB, as already demonstrated elsewhere [3,4,18,19,21,30,31]. Conversely studies from Nigeria and Brazil showed no association between maternal age and LBW or preterm birth [32,33]. The urban setting and the hospital-based recruitment in these studies may explain their finding.

In multivariate analysis anemic teenagers delivered more LBW or PTB newborns than their adults counterparts. Indeed anemia is more frequent in adolescents than in adults and it is linked to LBW and PTB [4,8,12,23,27,34]. The high frequency of anemia in teenagers may be explained by the inadequacy of their diet to fill the iron demand induced by their rapid growth and the menstruation’s onset [35,36]. Also, adolescents’ intake of iron folic acid for anemia prevention is lower compared to adults [29].

The risk of adverse fetal outcome in teenagers was the highest when they presented both anemia and fever. This is not surprising, considering the interplay of fever with anemia, and the role of malaria in the occurrence of fever anemia and LBW in endemic areas [37].

Although low BMI was frequent in teenagers and could indicate biological immaturity, this did not lead to a significant increased risk of adverse fetal outcome in our study as hypothesized elsewhere [2,31,38].

Our analysis excluded twins and this could underestimate the outcome, even if their number is limited. It was also not exhaustive concerning commonly analyzed covariates.

Nevertheless, the prospective design represents strength of our study. In addition, data were collected in an accurate and standardized way.

Importantly, the interplay of maternal age with the covariates was pointed out in our analysis. Inadequate number of antenatal visits has often been cited as deleterious factor of fetal outcome [12,39]. However, a free provision of quality health care including antenatal package was provided throughout the duration of the PREGACT trial.

Conclusion

Being a teenager is associated with adverse fetal outcome in the rural health district of Nanoro, mainly when teenagers experiment anemia and episodes of fever. In low resources setting, multidisciplinary approach including education and setting up favorable socio-economic environment are needed to prevent early motherhood.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Université catholique de Louvain (UCL) the Ph.D. grant. We thank also the data management personnel of Institute of Tropical Medicine at Antwerp in Belgium.

Funding

The PREGACT study has been funded by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership and co-funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation (BMGF)-USA, the Directorate-General for Development Cooperation (DGDC)-Belgium, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)- United Kingdom, the Netherlands-African Partnership for Capacity Development and Clinical Interventions Against Poverty-related diseases (NACCAP)- Netherlands, and the Medical Research Council (MRC)-UK.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research has been conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki and to the ICH Good Clinical Practices guidelines. The PREGACT study was approved from the Ethics committee of the University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium, the Institutional Ethics committee of Centre Muraz and the Ethics committee of the Ministry of Health, Burkina Faso. All the participants or their representatives gave informed consent before entering the study.

References

- UNFPA (2013) Adolescent pregnancy: The review of the evidence.

- Althabe F, Moore JL, Gibbons L, Berrueta M, Goudar SS, et al. (2015) Adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: The global network's maternal newborn health registry study. Reprod Health 12: S8.

- Fall CHD, Sachdev HS, Osmond C, Restrepo-Mendez MC, Victora C, et al. (2015) Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: A prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (COHORTS collaboration). Lancet Glob Health 3: e366-e377.

- Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Morisaki N, Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, et al. (2014) Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: A World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG 121: 40-48.

- Nove A, Matthews Z, Neal S, Camacho AV (2014) Maternal mortality in adolescents compared with women of other ages: Evidence from 144 countries. Lancet Glob Health 2: e155-e164.

- Jutte DP, Roos NP, Brownell MD, Briggs G, MacWilliam L, et al. (2010) The ripples of adolescent motherhood: Social, educational and medical outcomes for children of teen and prior teen mothers. Acad Pediatr 10: 293-301.

- Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, et al. (2012) Global, regional and national causes of child mortality: An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 379: 2151-2161.

- Chibwesha CJ, Zanolini A, Smid M, Vwalika B, Phiri Kasaro M, et al. (2016) Predictors and outcomes of low birth weight in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 134: 309-314.

- Doherty T, Jackson D, Swanevelder S, Lombard C, Engebretsen IM, et al. (2014) Severe events in the first 6 months of life in a cohort of HIV-unexposed infants from South Africa: Effects of low birth weight and breast feeding status. Trop Med Int Health 19: 1162-1169.

- Wang ML, Dorer DJ, Fleming MP, Catlin EA (2004) Clinical outcomes of near-term infants. Pediatrics 114: 372-376

- Borja JB, Adair LS (2003) Assessing the net effect of young maternal age on birth weight. Am J Hum Biol 15: 733-740.

- Feresu SA, Harlow SD, Woelk GB (2009) Risk factors for low birth weight in Zimbawean women: A secondary data analysis. PLoS ONE 10: e0129705.

- De-vienne CM, Creveuil C, Dreyfus M (2009) Does young maternal age increase the risk of adverse obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcomes: A cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 147: 151-156.

- Nambozi M, Mulenga M, Halidou T, Tagbor H, Mwapasa V, et al. (2015) Safe and efficacious artemisinin-based combination treatments for African pregnant women with malaria: A multicentre randomized control trial. Reprod Health 12: 5.

- Ballard JL, Khoury JC, Wedig K, Wang L, Eilers-Walsman BL, et al. (1991) New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J Pediatr 119: 417-423.

- The PREGACT study group (2016) Four artemisinin-based treatments in african pregnant women with malaria. N Engl J Med 374: 913-927.

- WHO (2007) Adolescent pregnancy: Unmet needs and undone deeds.

- Kongnyuy EJ, Nana PN, Fomulu N, Wiysonge SC, Kouam L, et al. (2008) Adverse perinatal outcomes of adolescent pregnancies in Cameroon. Matern Child Health J 12: 149-154.

- Mombo-Ngoma G, Mackanga JR, Gonzalez R, Ouedraogo S, Kakolwa MA, et al. (2016) Young adolescent girls are at high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: An observational multicountry study. BMJ Open 6: e011783.

- Medhi R, Das B, Das A, Ahmed M, Bawri S, et al. (2016) Adverse obstetrical and perinatal outcome in adolescent mothers associated with first birth: A hospital-based case-control study in a tertiary care hospital in North-East India. Adolesc Health Med Ther 7: 37-42.

- Egbe TO, Omeichu A, Halle-Ekane GE, Tchente CN, Egbe E, et al. (2015) Prevalence and outcome of teenage hospital births at the Buea Health District, South West Region, Cameroon. Reprod Health 12: 118.

- Wang SC, Wang L, Lee MC (2012) Adolescent mothers and older mothers: Who is at higher risk for adverse birth outcomes? Public Health 126: 1038-1043.

- Leppälahti S, Gissler M, Mentula M, Heikinheimo O (2013) Is teenage pregnancy an obstetric risk in a welfare society? A population-based study in Finland, from 2006 to 2011. BMJ Open 3: e003225.

- UNFPA (2015) Burkina Faso: Adolescents and youth country profile.

- Yugbaré SO, Kaboré R, Koueta F, Sawadogo H, Dao L, et al. (2013) Risk factors for death of newborns with low birth weight in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Journal de Pédiatrie et de Puériculture 26: 204-209.

- Njim T, Choukem SP, Atashili J, Mbu R (2016) Adolescent deliveries in a secondary-level care hospital of Cameroon: A retrospective analysis of the prevalence, 6 year trend and adverse outcomes. J Pediatr Adol Gynec 29: 632-634.

- Gibbs CM, Wendt A, Peters S, Hogue CJ (2012) The impact of early age at first childbirth on maternal and infant health. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 26: 259-284.

- Watson-Jones D, Weiss H, Changalucha J, Todd J, Gumodoka B, et al (2007) Adverse birth outcomes in United Republic of Tanzania-impact and prevention of maternal risk factors. B World Health Organ. 85: 9-18.

- Mukhopadhyay P, Chaudhuri RN, Basker P (2010) Hospital-based perinatal outcomes and complications in teenage pregnancy in India. J Health Popul Nutr 28: 494-500.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Lammers C (2005) Maternal-perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with adolescent pregnancy in Latin America: Cross-sectional study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 192: 342-349.

- Ganchimeg T, Mori R, Ota E, Koyanagi A, Gilmour S, et al. (2013) Maternal and perinatal outcomes among nulliparous adolescents in low and middle-income countries: A multi-country study. BJOG 120: 1622-1630.

- Awoleke JO (2012) Maternal risk factors for low birth weight babies in Lagos, Nigeria. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 285: 1-6.

- Neto M, Segre C (2012) Comparative analysis of gestations and frequency of prematurity and low birth weight among children of adolescent and adult mothers. einstein 10: 271-277.

- Demirci O, Yilmaz E, Tosun O, Kumru P, Arinkan A, et al. (2016) Effect of young maternal age on obstetric and perinatal outcomes: Results from the tertiary center in Turkey. Balkan Med J 33: 344-349.

- Pobocik RS, Benavente JC, Boudreau NS, Spore CL (2003) Pregnant adolescents in Guam consume diets low in calcium and other micronutrients. J Am Diet Assoc 103: 611-614.

- Beard JL (2000) Iron requirements in adolescent females. Proceedings of the symposium on improving adolescent iron status before childbearing. J Nutr 130: 440S-442S.

- Olatunbosun OA, Abasiattai AM, Bassey EA, James RS, Ibanga G, et al. (2014) Prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women at booking in the university of Uyo teaching hospital, Uyo, Nigeria. Biomed Res Int.

- Hediger ML, Scholl TO, Belsky DH, Ances IG, Salmon RW (1989) Patterns of weight gain in adolescent pregnancy: Effects on birth weight and preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol 74: 6-12.

- Kurth F, Belard S, Mombo-Ngoma G, Schuster K, Adegnika AA, et al. (2010) Adolescence as risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome in Central Africa: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 5: e14367.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5533

- [From(publication date):

August-2017 - Dec 18, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 4535

- PDF downloads : 998