Research Article Open Access

Living Will Awareness and Collective Trust between Physicians, Cancer Patients and Caregivers: A Qualitative Study

Tharin Phenwan1*, Patsri Srisuwan1 and Tanongson Tienthavorn21Department of Family Medicine, Phramongkutklao Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

2Department of Community and Military Medicine, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Bangkok, Thailand

- *Corresponding Author:

- Tharin Phenwan MD

Resident, Department of Family Medicine

Phramongkutklao Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

Tel: 66-89-8374898

E-mail: phenwant@gmail.com

Received date: December 10, 2014, Accepted date: January 20, 2015, Published date: January 29, 2015

Citation: Phenwan T, Srisuwan P, Tienthavorn T (2015) Living Will Awareness and Collective Trust between Physicians, Cancer Patients and Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. J Palliat Care Med 5:205. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000205

Copyright: © 2015 Phenwan T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Background: A living will is a form of Advance Directive (AD) that represents a patient’s wish, ensuring that their autonomy is respected and answered. However, after the Health Act Legislation in 2007, no practical assessment of living wills has been investigated in Thailand yet.

Aim: To explore living will awareness and attitude in cancer patients and their family caregivers.

Materials & Methods: Semi-structured interviews with purposive sampling method. Nine patients and five family caregivers at the Gyneoncology clinic from January 2014 to March 2014 joined the study. Three aspects were explored: awareness of and attitude towards living will, comprehension of medical terminology in the document, and decision-making. Data were coded and analysed using thematic analysis approach.

Results: None of the participants have heard of living wills before. Three themes emerged: (1) Past experiences about death and terminal illness play a major role in perception of illness, comprehension of the document, and decision-making, (2) Participants’ decisions were based on mutual trust of their family members and their doctors, reflecting Thai collectivist culture, (3) Patients’ and caregivers’ perception of illness and autonomy need to be assessed.

Conclusions: Larger scale assessment of living will awareness in Thailand is still needed. Perception of illness plays a major role regarding to AD and decision-making. Because of collective doctor-patient relationship, patients’ and caregivers’ perception of illness needs to be assessed before any AD is initiated. A joint meeting between family members and doctors is also a necessity, ensuring that the patient’s autonomy and the family’s concerns are thoroughly explored.

Keywords

Qualitative research; Advance directive; Living wills; Palliative care

Abbreviations

AD: Advance Directive; ACP: Advance Care Plan; CPR: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; DNR: Do Not Resuscitate; IRBTA: Institutional Review Board of the Royal Thai Army Medical Department; MBAI: Modified Barthel Activity of Living Index; NG: Nasogastric; NHCO: National Health Commission Office; PSDA: Patient Self Determination Act.

Introduction

A living will is a form of Advance Directive (AD) that represents a patient’s wish [1], ensuring that their autonomy, one of the principle biomedical ethics, stating that an individual should have the right to make their own decisions, is respected and answered [2]. Apart from their autonomy, it could also prevent medical futility that mostly occurs among terminally ill patients [3-10]. While most of their wishes are to have a high quality of life, being independent and complete their unfinished businesses, only half of the patients are able to communicate their needs to the family members and doctors [11]. Furthermore, health expenditure during terminal states is also much higher compared with other states of life, 24,856 USD and 3,699 USD respectively [12].

In the USA, the Patient Self Determination Act (PSDA) was formed since 1991 to prevent these outcomes. After PSDA implementation, most of the patients who made a living will had their wishes answered and could fulfill their unfinished businesses.

The cost of hospital stay for both parties also reduced drastically, emphasising the significance of living wills. After the successful launch in the USA, living will was then expanded into other countries because of its effectiveness [13].

In Thailand, however, palliative care service is still not generally available [14,15]. Even after the health act legislation in 2007[16], no practical assessment of living wills has been investigated so far.

Previous studies mainly focused on the healthcare provider [17]. Those emphasising on patients were performed in terminal cases during hospital admission and no studies had explored about AD in non-terminal cases and in the general population yet [18-20]. Family members, who are the major caregivers in Thailand, also have not yet been assessed about their understanding and awareness in regards to living wills [21,22].

The purpose of this study was to explore the awareness and attitudes of living wills among cancer patients in early stages and their family caregivers.

Methods

Study design

The author conducted semi-structured interviews with nine patients and five family caregivers at the Gyneoncology Clinic in Phramongkutklao Hospital between January 2014 and March 2014.

Purposive sampling method was used to select various ages, clinical staging and diagnosis for the study. After approaching the participants, the interviewer introduced himself then asked the participants about the purpose of their visit to assess if they were aware of the diagnosis.

After explaining the objective of the study, written informed consent was obtained and the participants then had an individual interview. The guidelines for the interview were derived from a living will document sample 1 designed by The National Health Commission Office (NHCO) of Thailand (Additional file 1) [23,24]. Family caregivers were addressed by either themselves or the patients. Data were gathered until saturation was reached.

Interviews

All of the interviews were video recorded for nonverbal language interpretation. Conversations were fully transcribed along with field notes and an audit trail immediately after each session. After demographic data collection, participants were asked if they ever heard of a living will then were given the document to read.

The interviewer answered any questions and gave further explanation to the participants until no more questions arose. The session continued after the participants had finished reading the document. Three aspects were explored: awareness of and attitudes towards living wills, comprehension of medical terminology in the document and decision-making. The interview took 30 to 50 minutes each session, depending on the participant.

Data Analysis

Open codes were created and analysed using investigator triangulation method. The codes were discussed, modified, and merged by the authors and final revised codes were developed afterward.

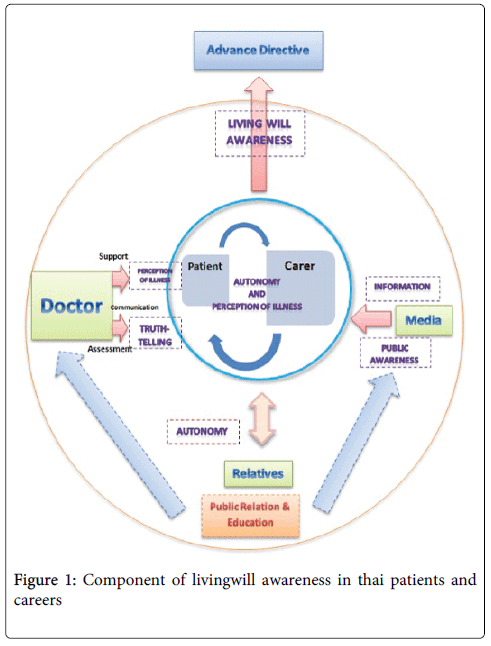

Emerging concepts were extracted and analysed using a thematic analysis approach. Themes were based on the model (Figure 1) and were described along with verbatim quotes from the participants.

Ethical Consideration

The Ethics Committee Board of the Institutional Review Board of the Royal Thai Army Medical Department (IRBTA) approved of this study. Participation was voluntary and did not affect their treatment in any way.

Results

Participant Characteristics

We interviewed nine patients (aged 30-61 years old) and five family caregivers (aged 28-60 years old) with different backgrounds. Patients had various stages of cancer, all of whom were totally independent with a score of 20 using the Modified Barthel Activity of Living Index (MBAI). All of the caregivers were relatives, four of whom were daughters while the other one was a husband (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Patient, N=9 |

Carer, N=5 |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| Mean +/- SD | 44 +/- 9.2 | 45.8+/-13.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Female Male |

9 - |

4 1 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Breast cancer | ||

| Stage IIa | 1 | |

| Cervical cancer | ||

| Stage I | 2 | |

| Stage II | 4 | |

| Stage III | 1 | |

| Ovarian cancer | ||

| Stage I | 2 | |

| Living will awareness No |

9 | 5 |

Table 1: Participant Characteristics; a One participant was diagnosed with both cervical and breast cancer.

Regarding the final hour of their lives, nine of the participants requested the Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) option while the other five wanted a proxy (Table 2).

| Decision | DNR | Proxy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | Relative | ||

| Patients | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Carers | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 9 | 4 | 1 |

Table 2: Participant’s decision in terminal stage.

DNR

“If I were to die, I want my doctor to help with everything they have. But no need to pump [CPR]! DON’T. Just let me die naturally. If I were to die, I want to pass away without any suffering.”

Proxy

Of five participants, four of them left the decision to their doctor and the other one to her family caregiver, her nephew.

“If anything happens, I would leave all of the decisions to my children and nephew. Whatever happens happened. Let her [nephew] do the rest.”

However, even with proxies, they still did not want any invasive treatment, especially those who experienced a negative impression with certain procedures before.

[When asked about treatment of choices in the document] “I can’t think of anything right now but no [NG] tube feed!! Someone who got better after that told me that it was so painful and miserable. It was so..pitiable..The pain… They just...lie there..like they didn’t know what was going on but they….[Quoting] “Ohhh…it hurts….ohhhhhhhh” I heard it so many times when I was there visiting my mum. The sound was just.oh.so dreadful”

Past experiences about death and terminal illness played a major role about perceptions of illness and decision-making.

None of the participants had heard of living wills before. When inquiring about the document, two of them thought it was a will, an official statement of what a person has decided should be done with their money and property after their death, whereas three of them thought it was a life insurance. This misunderstanding might partially have been caused by the Thai word, “Pinaikam Chi-vit/ ” (the life insurance/will), which was a misleading translation.

Thematic Analysis

After analysing final codes, three themes emerged (Table 3).

| Themes | Categories | Sub Categories | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past experiences about death and terminal illness play a major role about perception of illness and decision-making |

Experience | Direct | Used past experience as references. Used to be carers. |

| Indirect | Perceived through various sources, relatives, neighbours, news. “Internet medicine”. |

||

| Negative | Witnessed aggressive treatments or saw terminal patients. Negative experiences through the course of treatment. |

||

| Participant’s decision was based on mutual trust of their doctor and family member, reflecting Thai collectivism culture | Trust | Doctor | Have good doctor-patient relationship. Have doctor- knows-best attitude. |

| Relative | Believe that proxy would make the best decision for them. | ||

| Collectivism | Carer | “Think” that their decision is the best for patient’s well-being. Has collusion within the family. |

|

| Patient | Don’t want to be a burden. Worried about the rest of the family. |

||

| Patients’ and carers’ perception of illness and autonomy needs to be assessed |

Perception of Illness |

Fully understood | Being able to talk about ACP and AD. Have positive attitudes toward ACP and AD. |

| Not understood very well | Due to improper truth-telling process . From collusion within the family. |

Table 3: Themes, categories, subcategories, and codes of the participants after the interviews;ACP: Advance Care Plan; AD: Advance Directive

“Livng will… Is it about life insurance?”

After reading the document, 13 of them had positive attitudes toward the document.

“It’s good. From when I saw my gravely ill mother, there would be some tubes and….well..…she was…so delirious that she would pull all of those tubes all the time, feeding tube, IV fluids, and stuff. It was so miserable…so I don’t want the same thing happening to me.”

Another participant felt emotionally negative regarding to the document but added that it helped her to reflect about her illness. This could be seen as a positive attitude toward the document as well.

“It makes me feel kinda..sad...depressing….But it also got me to think about myself. What would I do if I were…in that [terminal] state?”

When asked about medical terminologies, medical procedures and decision-making, 12 of the participants related to their past experiences rather than from the document they just read.

[Definition of Nasogastric (NG) feeding] “I saw it. You have to put it [liquid food] through the…nose.”

[Indirect experience of Intubation] “The guy who got better after he was intubated told me that it was a very painful experience because they had to shove the tube in you. It hurts so much, he said.”

[Negative direct experience of intubation] “It was so painful..suffocating…like you can’t breathe at all. I heard someone calling me but I can’t [breath] It was [suffering]….so I loathe it and don’t want it again.”

Five of the participants, who did not have any prior knowledge and experience about medical terminology and medical procedures, failed to understand most parts of the document.

[When asked about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)] “I can’t answer that…I don’t have much experience about it [CPR], you know? So, I don’t [know]…... and the document that I read earlier? I don’t even pay much attention to it (chuckle).”

Nine had direct experiences with death and terminal patients and were aware of procedures they had witnessed before, such as NG feeding or CPR and used these experiences as references.

[When asked about definition of NG feeding]”Yeah [used to do it herself]…a tube. You feed them through here [tube]. See how they make a hole here?then I push the liquid food through there”

However, due to the document’s complexity and multitude of issues covered, some participants still did not fully understand the document even after a full explanation from the interviewer.

[When probed to explain about one of the medical terminologies] “I know about some words in there! (Sound upset) But you have to explain it too! I just get some part of it, not the whole thing!!”

Participants’ decisions were based on mutual trust of their doctor and family members, reflecting Thai collectivism culture

A homogenous finding regarding decision-making of the participants was the concept of trust. Doctors in Thailand are still highly regarded. All of the participants trusted their doctors explicitly, leaving most of the decisions to them and would follow their advice.

“I think I would leave the decision to my primary doctor if I should go on [treatment] with number one, two, or three. My husband also has a great credential about him. Something like..prolonging life, we won’t know these kinds of stuff better than a doctor. If my doctor says that it can be cured then it can, if he says that it could not be cured (chuckle) then, well, it can’t be cured, no?”

“Have to do everything according to my doctor. I follow everything he says.”

If the patients did not receive a clear explanation about their illness from their doctors, they often sought other sources, people who they trusted or even from the internet so that they could rely on the information they wanted.

[After she was diagnosed with cancer without a clear treatment plan]"I browsed through the internet and stuff. My friends and relatives also said that if I went through surgery, there is a very high chance of being cured. 100%, they said.”

When making comments about their own illness or decision-making during the final moment, almost all (7) of the patients took their family members into account.

[Reason for making a living will]"Another thing is that I always want to be independent. Don’t want to be a burden to other people [her family]”.

From another perspective, nearly all (4) of the caregivers transferred their thoughts regarding the illness and made decisions on the patient’s behalf too.

[When asked about the patient’s decision making]”I think…if it eventually comes to this (point at the living will).. about who would make the decisions.I....I….I will do it. Well, because..because.. she [his wife] would have trusted me? Because since the beginning of her treatment, I am the one who brought her here, doing things to make her better so…the rest is my duty, my obligation, to make decisions”

As for the Advance Care Plan (ACP), the answers were divided in two groups. The first group (five patients and four caregivers) had thought about ACP or already had made a verbal plan with their relatives.

[When asked about ACP]”Yeah….. Sometimes I just kept thinking….what if I were very ill? If it were that miserable then I want to…go [die]. No need for further suffering, no need to pump [CPR], no nothing. If I were that bad then I don’t want anything. Living like that is just being a burden to those who are left behind”

The second group (four patients and one caregiver), all of whom were patients and caregivers that did not have a clear understanding of their illness, did not think about ACP at all.

“Nope (shaking head). Not at all…I don’t want to think about it…don’t wanna. Because it’s too stressful..depressing….Don’t wanna think about it at all”

Patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions of illness and autonomy need to be assessed

Surprisingly, some of the participants (5) did not fully understand about their own illness or those they had been taking care of. This lack of understanding was partly due to the improper truth-telling process from the physicians or the lack thereof.

[When asked about her diagnosis and treatment plan]”It was not clear at all. They did chemo just twice..didn’t tell me that there would be be both chemo and radiation. They just told me after they did all of these. I know nothing (sound upset). Just twice [chemo]….then it came back [cancer] and all they did was just the chemo twice.”

[When asked about her diagnosis] “When I knew that I had cancer….At first, I didn’t know (smile sadly)….don’t know at all. My doctor didn’t tell me. After the operation, there was this one doctor who works here. He asked me that [Quotation] “Do you know about your diagnosis? What kind of operation have you been through?” “No”, I said (raised tone) “And your doctor didn’t tell you?” “No, he didn’t” “What!? Then why didn’t you ask!?” “I didn’t” “Well, do you want to know about your diagnosis?” “Yes, I do” Then he told me…..It was so shocking back then that how could this have happened to me? When I did the operation, I didn’t know…My husband also didn’t know, even my son..he..he also didn’t know”

On the other hand, participants with a clear understanding of their own illness or who had been diagnosed with cancer for a long time had a better understanding of the situation, which tended to ensure that their wishes had been communicated.

[ACP] “If I were that sick, dying, and someone just revived me, it’s more like a torture. If it’s still ok [being curative] that’s fine. But if the doctor said that it’s beyond help then I don’t..I don’t want it. I’m aware of that kind of situation. Just lying there and suffers. Well…I don’t want to suffer..I don’t..I don’t want it.”

Discussion

From these results, the first homogenous finding was that participants had positive attitudes toward living wills. They saw the document as a tool to deliver their wishes, prevent unnecessary suffering and help reflect upon their illness. They also believed that a living will was one of the effective methods to express their’ autonomy in a written, viable form rather than a verbal consent that may or may not be fulfilled at the terminal moment [7-9].

“I think it’s worth a try. If they send me here, right? If I have this [a living will] then the doctors can make it [decisions], right? My children won’t be able to make a call if my doctor asks them if they want to prolong my life or not. They won’t”

As for comprehension of the document and decision-making during terminal hours, almost all (11) of the participants used their past experiences as references. The reason past experiences had such a strong impact over the document might have been due to the fact that the document was too complicated and covered many issues so participants could not understand all of the new data and make decisions all at once. To prevent this and make the living will document more effective, multiple sessions and interactive discussions with resource persons are needed [6,7,10,13,22].

Moving to another theme, collectivism and mutual trust among family members and doctors, inarguably, had a huge impact on the Thai participants’ decisions [25-32].

Hofstede described Thailand as a country exhibiting a collectivist culture [25,26], which is also based on Buddhism [26-31]. Most of the time, autonomy among Thais expands as a whole family unit. An individual within the family unit usually thinks in place of other members and tries to make the best decision for them. However, this wishful thinking may or may not coincide with patients’ wishes at all. For example, caregivers may prevent the patients from knowing their diagnosis, believing that hiding information was for “the best”.

[When asked the reason why she would not disclose the truth that her mother has cancer]”No, I won’t tell her (firmly) because I know her nature. She’s easily frightened, you know? If she knew, instead of starting the treatment, she might not be able to take the news and that would be the end of it”

On the other hand, other participants may focus on the rest of the family members rather than on themselves.

[After the diagnosis] “We looked at each other..speechless..well, because our kids were still in school.. We talked about it and wished that I should have lived for another ten years. At least until they are all graduated”

These examples clearly showed that participants’ decisions were based on both patient and family aspects. Therefore, the decision making inevitably had to include the family members as well.

As for the ACP, some participants were not very eager to talk about it at all. This may have been caused by the patients being still in the early stage of the disease so they do not yet have a clear picture of themselves at the terminal stage or they still aimed for curative goals since few of them (3) were only recently diagnosed and had just initiated the treatment. Being a culture with a high ranking of the Uncertainty Avoidance dimension also made patients and family members not so keen to talk about their uncertain future too [25,26]. To prevent these and also reduce the effects of collectivist culture, decision-making regarding important topics would best come from joint meetings among patients and their family member to ensure that both the patient’s autonomy and family members’ concerns were thoroughly explored. Additionally, because the participants in this study had deep and mutual trust with their doctors, physicians need to give proper and thorough explanation regarding to patients’ illnesses and decision making so that their autonomy would not be neglected.

Regarding the last theme of perception of illness, one major factor is how participants perceive their disease. Even though patients are aware of their own disease, some of them do not fully understand about it, and thus lack a clear picture of what could happen to them afterward. Some patients even have been uninformed regarding their diagnosis and have had their autonomy reduced by relatives or doctors, either from improper truth-telling process, the influence of collectivism or both. Nevertheless, all of the patients who found out about their condition later were very upset, feeling that they had been neglected. The lack of understanding also explains why some (4) of the participants’ decision to leave all of the choices to their proxy too. Since proxies, family members and doctors, have more knowledge about the disease than patients themselves, for them to think that proxies would be a better judge of their clouded future was only logical.

This phenomenon leads to several suggestions. First, truth-telling is a very important step for patients to understand about their own illness and have been seriously overlooked. From this study, patients did want to know about their illness. It did not mean about the diagnosis itself but rather attaining closure and receiving an explanation about what has been going on and how they would proceed from now. A clear understanding of this could not have happened without a proper disclosure from doctors and family members due to the collectivist nature of Thais. Therefore, assessment of patients’ perceptions of illness is still a necessity to ensure that they truly understand about their disease, future treatment plan, thus leading to initiating ACP and AD with a clear understanding afterward.

In conclusion, all of the participants had not heard of a living will before and thus it was impossible to ascertain one of the primary objectives of the study, i.e., living will awareness in cancer patients and their caregivers. However, since all of the participants had positive attitudes toward the document, assessing this in a larger scale is noteworthy. These findings reflect an urgent need for strategies to promote living will awareness. Public relations, help from the media and education to raise awareness among both healthcare providers and the general populations on a larger scale are also still needed [24].

Recommendations

Living will awareness in Thailand needs further assessment.

Because this was the first study to explore living will awareness and attitudes in Thailand, further assessment is still needed. A study in a larger population will help us grasp a better understanding of the national situation and lead to proper interventions afterward.

Contents of living will document.

The document needs to be simplified so that readers could have a better understanding of the content. Multiple sessions with interactive explanations from medical personnel covering complicated topics such as medical terminologies and medical procedures also prove to be beneficial [6,7,10,13,22].

Timing for ACP and AD.

In patients with early diagnosis of cancer, talk about making a living will might be overlooked because most of them find it too early or stressful to talk about death and ACP. However, it does not mean that living wills should be totally ignored. Physicians need to individually assess the patient regarding the proper time to talk about it. Deteriorated health or living with cancer for a long period of time also increase eagerness to make a living will [6,22,23] so these other factors might be considered when timing the ACP. Another point is that before initiating any ACP or AD with patients, healthcare providers need to assess their understanding of their illness first. If they lack a clear understanding of the situation, the importance of ACP might be overlooked.

Among caregivers, due to the collectivist culture in Thailand, some may transfer their thoughts and make presumptuous decisions in the patients’ stead. Clarifying that a living will is a document made for them and not for the patients that they are taking care of is important.

Furthermore, to prevent the collusion, the ACP needs to be conducted and explained together with the family members so that patient’s and relatives’ wishes would not be overlooked. A joint meeting between family members and the patient may help to ensure that patients’ autonomy and family’s concerns are thoroughly explored [22].

Finally, a living will is merely one of many tools to help patients prepare concerning their illness and AD. Physicians still must use their judgment if the patient needs a living will for their AD or not.

Strengths

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first qualitative research in Thailand that delves into living will awareness in early stage cancer patients and their caregivers. The uniqueness of this study is that the interviews were conducted in an ambulatory setting, where early clinical stage of cancer patients gathered. Their perception of illness differed greatly from those who are in the terminal state or being admitted. Finally, many noteworthy issues emerged during the analysing process including the concepts of perception of illness, trust, and collectivism.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, the interviews were conducted in a large tertiary care hospital in the capital city. Participants’ answers may differ from another setting such as secondary care hospitals due to different socioeconomic factors and disease background. Second, despite using semi-structured interview guidelines, they were all one-session interviews. Important issues may have been missed or not explored thoroughly. Further mutual relationship between participants and the interviewer with multiple-session interviews may be needed to delve more deeply regarding complicate and sensitive issues. Furthermore, many interesting emerging issues from the interviews were not explored much further due to the fact that they were not the main objectives of the study. In addition, this study did not include those who were already aware of or had already made a living will; thus, we cannot deduce anything from this missing group. Plus, there were translation bias in quotations of this work. We first conducted the interviews and made audit trails in Thai. Afterwards, with the help of a native English speaker, we decided to leave grammatical errors and erroneous phrases as they were to reflect how the participants, all of whom have different socioeconomics and educational background, replied during the interviews. However, this process also leads to mistranslation of English expression to some extent. Finally, just like another qualitative research, participants were selected and voluntary. The thoughts of non-participating subjects were impossible to ascertain. Such is an inevitable weakness of all qualitative (and also quantitative) research.

Conclusions

Larger scale assessment of living will awareness in Thailand is still needed. Perception of illness plays a major role regarding to AD and decision-making. Because of collective doctor-patient relationship, patients’ and caregivers’ perception of illness needs to be assessed before any AD is initiated. A joint meeting between family members and doctors is also a necessity, ensuring that the patient’s autonomy and the family’s concerns are thoroughly explored.

Authors’ contributions

TP conceived and designed the study, drafted the manuscript, carried out the interviews, video-recording, and performed codes analysis. PS and TT participated in the design of the study, helped to draft the manuscript, and also performed the codes analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our gratitude to the patients and caregivers who participated in this study. We also thank Dr. Thanarpan Peerawong for his constant help.

References

- http://www.thailawonline.com/en/family/living-wills-in-thailand.html

- Christman, John, "Autonomy in Moral and Political Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Sahm S, Will R, Hommel G (2005) Would they follow what has been laid down? Cancer patients' and healthy controls' views on adherence to advance directives compared to medical staff. Med Health Care Philos8: 297-305.

- Sahm S, Will R, Hommel G (2005) What are cancer patients' preferences about treatment at the end of life, and who should start talking about it? A comparison with healthy people and medical staff. Support Care Cancer13: 206-214.

- Sahm S, Will R, Hommel G (2005) Attitudes towards and barriers to writing advance directives amongst cancer patients, healthy controls, and medical staff. J Med Ethics 31: 437-440.

- Tamayo-Velázquez MI, Simón-Lorda P, Villegas-Portero R, Higueras-Callejón C, GarcÃa-Gutiérrez JF et.al (2010) Interventions to promote the use of advance directives: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient EducCouns80: 10-20.

- Evans N, Bausewein C, Meñaca A, Andrew EV, Higginson IJ, et al. (2012) A critical review of advance directives in Germany: attitudes, use and healthcare professionals' compliance. Patient EducCouns 87: 277-288.

- Escher M, Perneger TV, Rudaz S, Dayer P, Perrier A (2014) Impact of advance directives and a health care proxy on doctors' decisions: a randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 47: 1-11.

- Santonocito C, Ristagno G, Gullo A, Weil MH (2013) Do-not-resuscitate order: a view throughout the world. J Crit Care 28: 14-21.

- del Pozo Puente K, Hidalgo JL, Herráez MJ, Bravo BN, Rodríguez JO, et al. (2014) Study of the factors influencing the preparation of advance directives. Arch GerontolGeriatr 58: 20-24.

- Rakel RE, Storey P (2007) Care of dying Patient. In: Rakel RE, editor. Textbook of family practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsvier 107-126.

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. Costs of death and health expenditure: Technical Paper 13 [Internet]. Melbourne: Australian Government Productivity Commission; 2013 [cited 2013 Dec 16]. Available from: http://www. pc.gov.au/ __data/ assets/ pdf_file/ 0007/ 13696/ technical paper 13.pdf.

- Rurup ML, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, van der Wal G, Deeg DJ (2006) Frequency and determinants of advance directives concerning end-of-life care in The Netherlands. SocSci Med 62: 1552-1563.

- http://www.who.int/cancer/country-profiles/tha_en.pdf?ua=1

- http://aphn.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Health-Policy-of-Government-2014-EN.pdf

- Martinez CH, Kim V, Chen Y, Kazerooni EA, Murray S, et al. (2014) The clinical impact of non-obstructive chronic bronchitis in current and former smokers. Respir Med 108: 491-499.

- Knowledge and understanding of palliative care with patients' rights to choose life: academic year. Memorial Professor Dr. Wee Sethabutra Tuesday, January 17, 2555 / [funds Professor Dr. Wee Sethabutra].

- Sittisombut S, Love EJ, Sitthi-Amorn C (2005) Attitudes toward advance directives and the impact of prognostic information on the preference for cardio pulmonary resuscitation in medical in patients in Chiang Mai University Hospital, Thailand. Nurs Health Sci7: 243-250.

- Sittisombut S, Maxwell C, Love EJ, Sitthi-Amorn C (2008) Effectiveness of advance directives for the care of terminally ill patients in Chiang Mai University Hospital, Thailand. Nurs Health Sci 10: 37-42.

- Sittisombut S, Inthong S (2009) Surrogate decision-maker for end-of-life care in terminally ill patients at Chiang Mai University Hospital, Thailand. Int J NursPract 15: 119-125.

- Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD (2007) The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 33: 486-493.

- McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, Sudore RL (2013) Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage 46: 355-365.

- http://en.nationalhealth.or.th/sites/default/files/Living_Will_Samples%201_Final.pdf

- Thorevska N, Tilluckdharry L, Tickoo S, Havasi A, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, et al. (2005) Patients' understanding of advance directives and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Crit Care 20: 26-34.

- Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ (2005) Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. 2 nd ed. London: McGrew-Hill.

- Pimpa N (2012) Amazing Thailand: Organizational Culture in the Thai Public Sector. International Business Research 5: 35-42.

- Sheehan B, Egan V (2007) Managing the Process of Continuity-in-Change in Thailand. In: Chatterjee SR, Nankervis AR, editors. Asian Management in Transition: emerging themes. Basingstoke [England]; New York.: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ritjaroenwatthu T, Yodmalee B (2009) The use of Buddhist economic principles in management of natural drinking water for community economic in Isan. European Journal of Social Sciences 10: 387-395.

- Soommaht C, Boonchai P, Chantachon S (2009) Developing model of health care management for the elderly by community participation in Isan. The Social Sciences 4: 439-442.

- Sowattanangoon N, Kotchabhakdi N, Petrie KJ (2009) The influence of Thai culture on diabetes perceptions and management. Diabetes Res ClinPract 84: 245-251.

- Stonington S (2011) Facing death, gazing inward: end-of-life and the transformation of clinical subjectivity in Thailand. Cult Med Psychiatry 35: 113-133.

- Stonington SD (2012) On ethical locations: the good death in Thailand, where ethics sit in places. SocSci Med 75: 836-844.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14180

- [From(publication date):

January-2015 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9590

- PDF downloads : 4590