Lived Experience of Caregivers of Relatives with Alcohol and Opiate Dependence (A phenomenological study)

Received: 23-Jun-2020 / Accepted Date: 24-Jul-2020 / Published Date: 01-Aug-2020 DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000395

Abstract

Substance abuse is a relapsing chronic illness. In 2014, an estimated 27 million persons reported using illicit drugs in the United States. Substance abuse negatively impacts societies, productivity, healthcare costs and families. Families play an important role in relapse prevention and sobriety. With adequate family support, substance abuse positively responds to treatment. Many individuals (about 66 million Americans) serve as an informal caregiver for a relative with chronic illnesses such as substance abuse but few studies exist on the caregiving experiences. What we know about the family caregiving experience is restricted to data from quantitative studies which do not explain the complexities and competing challenges that exist. Different approaches are thereby needed to deepen our understanding of the family caregiver burden of living with a relative with substance abuse problems. Such studies will enable us to understand the original experience and moment of learning of a relative’s substance abuse problems along with the decision making and support that follows thereafter.

The purpose of this study was to explore the lived experience of caregivers of relatives with alcohol and opiate dependence. This study utilized Max van Manen’s (2014) Phenomenology of Practice. Ten participants (N=10) were recruited for this in-depth study. Van Manen’s guided existential inquiry was used in the analysis of experiential material collected through interviews. Four main themes emerged from the data: (1) Being in the moment: the extension of the self; (2) The dawn of reality: the being of acceptance; (3) Deciding in the moment: the healthcare experience; (4) Uncertainties and struggle: a lifelong process. These themes described how the participants: experienced, accepted and processed a relative’s substance abuse problem, encountered treatment services and experienced the uncertainties and struggles involved in caring for a relative with substance abuse problems. Two interrelated findings emerged from these themes; the impact of guilt and stigma on seeking care and the need to see addiction as a disease rather than a moral character failure. This calls for coalitions with stakeholders to decrease stigma, enhance acceptance process and increase access to treatment.

Keywords: Uncertainties; Struggle; Stigma

Introduction

Substance abuse is a relapsing chronic illness. In 2018, an estimated 164.4 million persons (60.2 percent of the population aged 12 or older) reported using illicit drugs in the United States in the past month [1]. Substance abuse is currently on the rise with a concerning impact on families, societies, and communities. Many individuals in the United States find themselves as an informal and unpaid caregiver for a family member with chronic illness [2]. It is estimated that about 66 million Americans claimed providing unpaid care as a family caregiver to at least one relative or friend [3]. This includes all carers and does not differentiate those caring for persons with substance abuse. Caregivers have a key role in supporting family members/relatives with substance abuse and mental illness, but their contributions are frequently undervalued by mental health nurses and other health clinicians [4]. Caregiving for a loved one with a chronic condition including substance abuse has benefits including personal fulfilment and relief of suffering [5,6]. However, caregiving also has its associated stressors/burden.

Previous studies on the construct of burden of care have investigated several determinants and factors that have been attributed to the caregiver’s perception of burden of care [7]. Extant literature has put forth strong evidence between these determinants and burden of care in the family of the affected individual [8]. Though studies on the burden of care of chronic illness on families have focused on individual conditions such as anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dementia, and cardiovascular diseases [8,9], few studies exist on the burden of care of substance abuse on families. What we know about this phenomenon is restricted to data from quantitative studies which do not explain the complexities and competing challenges that exist. The majority of caregiving burden relating to substance abuse rests on family members; however, little is known about their problems and experiences [10].

Understanding the experiences of caregivers of family members with substance abuse is important not only for the caregivers themselves but because of their role in relapse prevention and treatment. Evidence suggests that effective methods involving increased participation of the family are needed in treatment and relapse prevention [11]. The family is recognized as the most protective factor [12] and the primary source of continuous care. Acquiring a better understanding of the family burden has become increasingly important as families adopt a major role in the care of their relative [13]. This calls for a multi-factorial approach to understand the multiple concepts involved in caregiving in families of the addicted individual. Therefore we need to know more about the burden of addiction from the perspectives of family caregivers.

The purpose of this research was to explore the lived experience of caregivers who have a relative with opiate and/or alcohol dependence problems. The study utilized van Manen’s phenomenology of practice [14]. There is the need to design studies that focus on the relative’s prereflective experiences. This will allow us to explicate the original sources of the lived experience; “for…there is nothing more meaningful than the quest for the origin, presentation, and meaning of meaning [14]. Such studies will enable us to be aware and comprehend a deeper multifaceted understanding of the phenomenon of addiction. In order to deepen and contribute to our understanding of this phenomenon the following research questions were explored:

1. What is it like to live with and care for a relative with opiate and/or alcohol dependence?

2. What alliances, resources, and supports does the family caregiver receive from healthcare providers?

Background and Significance

A family caregiver is a friend or relative who provides unpaid assistance to a person with a chronic or disabling condition [2]. Family caregivers today have an increased level of responsibilities because more adults with disabilities and chronic conditions live at home than ever before [6]. Families who assume roles as caregivers often have minimal support or preparation, thereby being burdened by these roles [15]. However, the experience of caregiving can also have positive dimensions such as personal fulfilment.

Substance abuse

There has been a recent resurgence in alcohol and drug use [16,17]. Alcohol has been reported to be the most abused substance in the U.S. About 139.8 million Americans reported current alcohol use, 16.6 million Americans classified themselves as heavy alcohol users, and 14.8 million people met criteria for an alcohol use disorder [1]. In 2013 about 169,000 Americans reported using heroin for the first time [18]. In 2018, 2 million Americans met criteria for opioid use disorder [1]. Addiction is similar to other chronic illness because they all have distinct biological and behavioral patterns [19]. However, addiction is different from other chronic illness as it relates to societal stigma, legal consequences of drug use, and guilt/shame.

Burden in this study refers to the experiences of caregivers as they care for their relative with alcohol and opiate abuse problems and their encounter with the healthcare system. Three main themes describing the burden of substance abuse on caregivers were identified in the literature. These are: subjective burden, objective burden, and addiction as a chronic relapsing disease.

Subjective burden is the social, psychological and emotional impact experienced by caregivers [20]. Subjective burden reported by caregivers of substance abusers includes; guilt, anxiety, depression, stigma, and worry. Subjective burden was seen as an important concept among this population. Family caregiving also has effects on the quality of life of caregivers. Main determinants of quality of life reported by participants were psychological health, social relationships, loss of time from work, financial loss, limited time for leisure and socializing, health effects from distress, chronic medical conditions, increased use of tranquilizers and antidepressants, and disruptions in family as a result of addictive behaviors [21-24].

Objective burden is the physical effect of the day-to-day tasks caregivers undertake for their family members [23]. Objective burden to family caregivers include financial and time commitment. Studies have reported that family caregivers spent between 16% and 19.8% of their income on non-medical expenditures directly related to their family member’s substance abuse [25]. Also, family caregivers spent between 21.2 and 32.3 hours per month providing informal care [25]. Time spent in assisting a care recipient reduces available time for work thereby lowering family earnings.

Addiction as a chronic illness is characterized by relapses and remissions. Brown and Lewis [26] have proposed four stages of a developmental model of recovery. These are: active alcohol/drug use, transition to recovery, early recovery, and ongoing recovery. This model exemplifies the chronic and potentially relapsing nature of substance abuse. It depicts how the family caregiver burden might be different at each of the different stages of recovery. Even during the phase of recovery, caregivers experience a constant fear of relapse.

Study Rationale And Innovation

Addiction, as with any other disease can be debilitating to families. The struggles, fears and uncertainties families go through as a result of addictive behaviors of a family member and even the destructive effects on the addicted family member are all phenomena with deeper meanings. Understanding addiction and its toll from the perspectives of caregivers will contribute to effective and efficient ways of involving them in the care of this population. Research is needed to understand this burden in order to identify strategies to offset caregiver stressors for improvement in health outcomes [6].

This study will explore the primordiality of the human phenomenon of caring for family members with addiction using van Manen’s phenomenology of practice. This includes the original experience and moment of learning that a relative has an addictive behavior and the acceptance, decision making and support that follows thereafter. This moment calls for major decision making, encounters with treatment services, and the burden of care. Insights will be gained by reflecting on these experiences thereby allowing for deeper understandings of dimensions of meanings of the extraordinary and mostly ordinary decisions that relatives encounter.

Conceptualizing family caregiver burden: The organizing framework

Phenomenology and theory: Phenomenology is both a philosophic and a research methodology [27]. “Phenomenology does not offer us the possibility of effective theory with which we can explain and/or control the world; rather it offers us the possibility of plausible insights that bring us in more direct contact with the world” [14]. “Phenomenology studies the world as we ordinarily experience it or become conscious of it before we think, conceptualize, abstract, or theorize it” [14]. As an example, in studying the caregiver burden of addiction, it is important to describe directly ways that this phenomenon arises and how it presents itself in the life of the caregiver.

The method of phenomenology of practice

Phenomenology of practice is an interpretive form of inquiry which combines philosophical, philological, and human science methods. Phenomenology as a method abstemiously reflects on structures of lived experience [14]. Pathos, as van Manen claimed is what drives the phenomenological method; “being swept up in a spell of wonder” about how a phenomenon appears, shows, presents, or gives itself to us [14]. By this, wonder is not amazement, marveling, admiration, curiosity or fascination [14]. In a state of wonder, the extraordinary is seen in the ordinary, strange in the familiar and unusual in the usual when we hold daily existence with our phenomenological gaze [14]. “Phenomenology is more a method of questioning than answering, realizing that, insights come to us in that mode of musing, reflective questioning and being obsessed with sources and meanings of lived experience [14].

Human science methods

Phenomenology of practice relies on human science empirical methods in the collection of pre-reflective experiential data for insightful phenomenological meaning.

Sample and setting

Sample size in phenomenological studies should be enough to gain examples of experientially rich descriptions [14]. A purposive sampling technique was used to identify participants for this study. Phenomenal variation; a type of purposive sampling [28] was utilized to identify caregivers of persons with alcohol and/or opiate abuse. This type of sampling included variation in length of diagnosis, time of diagnosis, and length of caregiving. This allowed for rich experiential material. Snowballing technique as described by Polit and Beck [29] was utilized to ask previously interviewed participants to recommend other family caregivers who may be interested in study. Ten (10) participants were recruited from two hospital-based mental health centers within a health care system in the North-eastern United States. Study flyers was handed to caregivers of persons with alcohol and opiate dependence inviting them to participate in the study.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria include: primary family caregivers (wife, husband, son, daughter, or son or daughter in-law) providing physical and emotional support to persons with opiate and/or alcohol abuse, English speaking and 18 years or older, Cognitive capacity to give a written informed consent was determined by a mini mental status exam. Caregivers who were chemically impaired were excluded from the study.

Human subjects protection

The researcher obtained permission from the health system’s Institutional Review Board to use these centers as data collection sites with an intra-agency agreement at the researcher’s school. Informed consent was obtained for each participant by the PI.

Interview approach

A challenge of phenomenological interview is to get participants to actually narrate their experiential account pre-reflectively [14]. The following modes as explicated by van Manen [14] served as a guide for the interview process.

Participants were invited to choose an interview setting that they found conducive to sharing their experiences and safe such as their homes, coffee shops or even in their cars. A personal connection was developed through friendly communication and casual conversation before seriously easing into the topic of interest. Recruitment was not done during the winter holiday season as this is typically a sensitive period for families.

Data collection

An interview method of collecting data was used with all interviews conducted by the principal investigator in participant’s home or location of the participant’s choosing. Semi-structured in-depth phenomenological interviews (Table 1: Flexible Interview guide) were utilized with each participant, being attentive to participants’ body language, facial cues, and non-verbal language when certain key moments of this experience were being explored. Data was collected between January and July of 2016.

| Flexible Interview Guide |

|---|

| The philosophical underpinnings of Phenomenology of Practice do not rely on mechanistic means for assessing human consciousness but rather allow for resourcefulness and innovation on the part of the researcher. The response of a participant to an initial question guided the nature of further probing questions, taking into consideration the burden of these question on the participant. |

| 1. Can you tell me what is it like to live with and/or care for a relative with alcohol or opiate abuse? |

| 2. How did you find out that your relative is abusing drugs? |

| · What was it like for you? |

| · What was your initial reaction? |

| · Can you describe in detail with a specific moment of this experience that still resonates with you? |

| · What was said, what happened thereafter? |

| 3. Can you describe the moment that you learnt your relative has addictive problem? |

| 4. How has your encounter with the health care system been? |

| · Who initiated treatment for your relative? |

| · Any specific examples of structures that needs to be improved in the delivery of care? (Please include specific examples as it relates to your case…it can be stories) |

| 5. What is the nature/structure/kind of support that your relative needs/receiving from you? |

| 6. Describe what you do as the primary caregiver for your relative? |

| · How did you assume the caregiver role? |

| · How did you prepare for this role? |

| 7. As a primary caregiver, do you receive any support from other family members, community resources or support groups? |

| 8. In what ways have you grown or developed from this experience of caring for your relative? |

| 9. What has the meaning of the experience of caring for your family member been for your life?" |

Table 1: Flexible interview guide.

Data management

All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist. Each participant’s interview and corresponding transcript were assigned a code. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic information.

Data Analysis

Reflecting on experiential material: Max van Manen has explicated various methods to reflect on experiential material which was utilized in the study. These are,

Thematic reflection: meanings embodied in the text of the interviews were attended using macro and micro thematic levels. At the macro thematic level, these texts were attended as a whole. Micro thematic level selectively attends to passages, phrases, words of the text.

Guided existential reflection: insight into the phenomenon of addiction was gained through exploring meanings and possibilities other than some predestined formula or mechanical way of doing things. Heuristic life world themes such as corporeality (lived body), temporality (lived time), spatiality (lived time), relationality (lived other), and materiality (lived things) were explored. By this, the phenomenological writing text included experiential materials in the form of quotes with insightful meanings.

Linguistic reflection: Close attention was paid to the language participants used to describe the phenomenon of addiction. This involved reflecting on the sources of words (etymology) and conceptually exploring similarities and differences in meanings of words.

Exegetical reflection: Texts were read with sensitivity and criticality. Here, related phenomenological literature was explored to seek meanings.

Methodological rigor

Max van Manen’s [14] criteria for evaluative appraisal of phenomenological studies was used to establish methodological rigor. These include: Heuristic questioning (to induce a sense of wonder), Descriptive richness (rich and recognizable experiential material), Interpretive depth (reflective quotes), Distinctive rigor (critical selfquestioning), Strong addresive meaning (embodied, communal, temporal, or situated self), Experiential awakening (vocative and persuasive language), and Inceptual epiphany (insight for professional practice, human actions, ethics and life meanings).

Findings

Demographic data is provided in Table 2. Participants reported a mean of 12.4 years (range 4-40 years) of caring for a family member with 3-40 hours per week (mean=10.7). Sixty percent (n=6) reported alcohol as their relative’s primary drug of abuse, whilst forty percent (n=4) reported heroin. Only fifty percent (n=5) reported that their relative were diagnosed by a psychiatrist with an alcohol and/or opiate abuse problems.

| Category | Number | Percent | Mean | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.5 | 31-69 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | 10% | ||

| Female | 9 | 90% | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 10 | 100% | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 7 | 70% | ||

| Single | 1 | 10% | ||

| Widowed | 2 | 20% | ||

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 8 | 80% | ||

| Retired | 2 | 20% | ||

| Caregiver Relationship | ||||

| Son | 3 | 30% | ||

| Daughter | 1 | 10% | ||

| Brother | 2 | 20% | ||

| Husband | 1 | 10% | ||

| Father | 1 | 10% | ||

| Mother | 1 | 10% | ||

| Son-in-law | 1 | 10% |

Table 2: Demographic information (N = 10)

Four main themes emerged from participants’ interviews. These are: Being in the moment: the extension of the self, the dawn of reality: the being of acceptance, Deciding in the moment: the healthcare experience, Uncertainties and struggle: a lifelong process.

Theme 1 Being in the moment: The extension of the self

This theme explores the meaning of how the self (caregiver) relates to the other (relative) and how the self is experienced in the early awareness of having a relative with alcohol and opiate abuse problems. In the moment of the experience, the caregiver suspects the existence of a problem that is usually “something” and confronts the relative. The caregiver was initially made to believe by the other of the non-existence of such suspicions. However, that “something” being questioned was usually corroborated by certain behaviors evident in the relative. Caregivers in the moment of everydayness of life usually failed to notice this as a sign of a deep-rooted problem. In the moment of everydayness, what was unusual in the usual, extraordinary in the ordinary, and strange in the familiar [14] failed to make itself known to the caregiver. The moment of everydayness depicts the pre-reflective mode (natural attitude) of human consciousness. In this pre-reflective mode caregivers rarely questioned the world around them; thereby, the “being” of the totality of the world was taken for granted. In the natural attitude thoughts have been so accustomed to the everydayness of life that phenomenon was usually experienced without concern or doubt. Three features emerged from this theme; Suspicions, Disbelief and Secret (Figure 1).

Suspicious: At times, signs of the possibility of the existence of the phenomenon might be present but caregivers unconsciously repressed these unwanted feelings about the relative from conscious awareness. A participant stated;

“Now that I look back, I see signs and symptoms that addiction was there. But I overlooked them as part of not wanting to think that it was a problem, and thinking that it was just experimentation or recreational use that a lot of teenagers or college students go through. I looked at it as, ‘It’s just a phase and didn't realize that it was really an abuse problem leading to addiction”.

Disbelief: The bringing into awareness consciously of that which has been suppressed unconsciously by caregivers of their relatives’ addictive problems was usually met by disbelief, which was characterized by charged emotions, upset feelings, surprise, hopelessness, helplessness and vulnerability. The surprise and disbelief of the existence of such a phenomenon was compounded by the initial belief that the diagnosis of a substance abuse disorder or the exhibition of substance abuse behaviours was a “moral character defect”.

“I felt hopeless and helpless because it wasn't anything medical. I looked at it as morally that she made some bad decisions that led her into this. I believed at that point that it was a moral character defect, as opposed to the disease that I now know it is. So when I found out that her substance use was at that degree, it was very disheartening, and I felt that we failed somewhere along the line”.

Secret: Caring for a family member with addiction problems is relational. Hence for confidentiality or the covering of the problem to exist, conscious efforts was made by the caregiver to conceal it.

“I didn't want her to be judged, and I just didn't want to hear all the negative that I believed I would hear. So I covered up initially and acted as though she had a medical problem. I even remember one time, when she was hospitalized, that I said that she had a kidney infection because I couldn't fathom saying that it was substance abuse and letting it out. I felt that it was a secret at that time.”

Theme 2 The dawn of reality: The being of acceptance

The acceptance of a human phenomenon of addiction of a relative is seen as a process. This theme describes how participants process and accept a relative’s substance abuse problems. Four features emerged from this theme; being of reality, stigma, guilt and acceptance as an insight (Figure 2).

The being of reality: Acceptance as a “being” of reality is a process that happens over time. Acceptance begins with the recognition of a situation or phenomenon which usually has “uncomfortable” feelings. Caregivers may be aware of the existence of a phenomenon of addiction but consciously decide not to bring into awareness its acceptance. This may be due to how the phenomenon presents itself or what it signifies. Realization thereby does not necessarily lead to acceptance.

“And I think another part that’s difficult, is that you're always thinking this back and forth thing. ‘Oh, he doesn't really have a problem.’ ‘Oh, he does have a problem.’ And obviously we knew he had a problem, but in the back of your head sometimes you don’t want to accept that easily.”

Stigma: The acceptance of a substance abuse disorder of a relative was usually tied to societal stigma. Stigma then becomes a hindrance in the acceptance process. Societal stigma may assume the form of an objection implicitly expressed towards the relative by others. Caregivers felt the phenomenon has been personified to represent something that is contagious.

“They immediately said, ‘No, he can't be in our home.’ Like, ‘He’s not welcome in our home.’ And I’m, like, ‘Well, he doesn't have the plague.’ It’s not contagious. I felt embarrassed”.

Guilt: Guilt was a common component in the acceptance process. Also, inaction of caregivers as it relates to an early treatment intervention was perceived to heighten the level of guilt. When guilt is overcome, acceptance is brought into conscious awareness. Acceptance may also be mediated by seeking information to learn about and understand the phenomenon of addiction.

“I felt as a parent that we did something wrong to create this. Sometimes I have the guilt, only because I’ve found out along the way that there was an early childhood sexual trauma that I did not know about. So I do still sometimes feel a level of responsibility for not recognizing that, that that happened as, as a child.”

Acceptance as an insight: Further, caregivers learned to cope and live with their relative despite the presence of substance abuse. At times, acceptance came in the form of acknowledging that a relative’s motivation and readiness to change were processes beyond the control of a caregiver. Acceptance finally occurred when caregivers sought for education leading to personal growth as it relates to substance abuse.

This experience led to personal growth that is transformational. A participant stated;

“Well, in the beginning I really had a hard time wrapping my head around this, so I realized that I needed to get appropriate support and education around this. And I did seek that help out, and through that I was able to wrap my head around what this was all about. So as I moved through the process and I became more educated about addiction, it became a lot easier to be able to take care of her and help her through it. I think that having educated myself in the area, now I feel much more able to share it. As I move forward I treat this as though she has a chronic illness, and I support her with her illness… is that you need to look at this like it’s a disease.

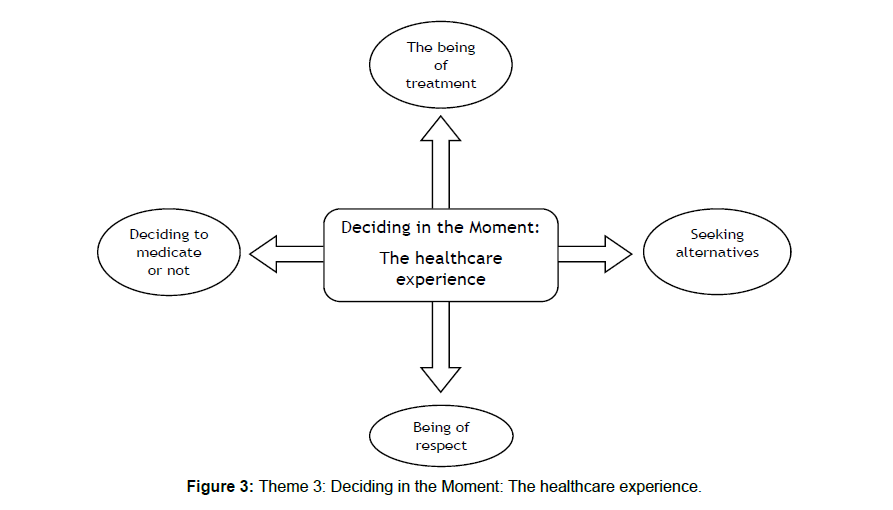

Theme 3 Deciding in the moment: The healthcare experience

This theme describes how participants encounter and experience the healthcare system as their relative with a substance abuse problem seeks care. Four features emerged from this theme; deciding to medicate or not, the being of treatment, seeking alternatives, and being of respect (Figure 3).

Deciding to medicate or not: Family caregivers reported that the healthcare experience often resulted in medication prescription. Caregivers were initially expecting an experience for their loved one that was less invasive, that which encouraged the expressions of feelings and emotions therapeutically; a cathartic experience. There was usually a decisive moment where caregivers were torn between either to medicate or not to medicate.

“It’s just that they were so quick to throw so many drugs at him, and even ones that, when I read all the side effects and the dangers and the cautions, no one was paying attention to. And that, I thought, ‘Oh, my God.’ You know, all this man needed probably was some good talk therapy and get this whole thing, you know, out in the open, rather than, let’s drug him. Let’s drug him some more. Let’s give him some more drugs.”

The being of treatment: Caregivers expressed their frustrations with the healthcare system as they sought care for their relatives. Here, they encountered some of the bureaucracies and hindrances. The frustrations in seeking care for their relatives were also manifested when there was an actual attempt to contact healthcare facilities. The resultant reality of the availability of treatment services/facilities and other resources became evident. Care is sought but to the dismay of caregivers, resources were limited; a mismatch of reality. A participant stated;

“It was like one of the last times he overdosed before he passed. He really wanted help so we called 50 different detox programs and no one had a bed, no one would take his insurance. It was the run-around. And then after that he just got frustrated and he was, like, well no one wants to help me so why should I help myself?”

Seeking alternatives: In as much as the healthcare system was the means utilized in addressing concerns about a family member’s addiction, other caregivers viewed it as not the only resource or the place where they can find answers. Other resources was sought from sources such as spiritual groups or psychosocial therapy sources. Participants also described self-help groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and Al- Anon as important supports.

“She does attend regular substance abuse therapy and individual therapy, but her strongest asset that she has found to help her is through church and through spirituality and through God, attending Bible groups, going to the church and being around people that are extremely supportive to her. “So, yes, wonderful people from the healthcare system. I’m not sure that’s the only arena that you have you need to access. I’m not sure they have all the answers.”

Being of respect: Family caregivers reported respect as an important component in the delivery of care. Being respected as described by family caregivers means being acknowledged. In demanding respect, caregivers described going through a process of seeking education and increasing knowledge base of care-related issues regarding addiction. In other words, family caregivers felt supported and listened when they were treated with dignity and respect. Dignity and respect start when addiction is considered as a disease and not as a social character defect.

“I believed that she was treated subserviently, as well as I was, in the beginning. But as I moved through the process, gained knowledge and education, I now, and maybe a couple years into it, realized that I had to become an advocate and I had to not allow healthcare-givers to treat us subserviently”

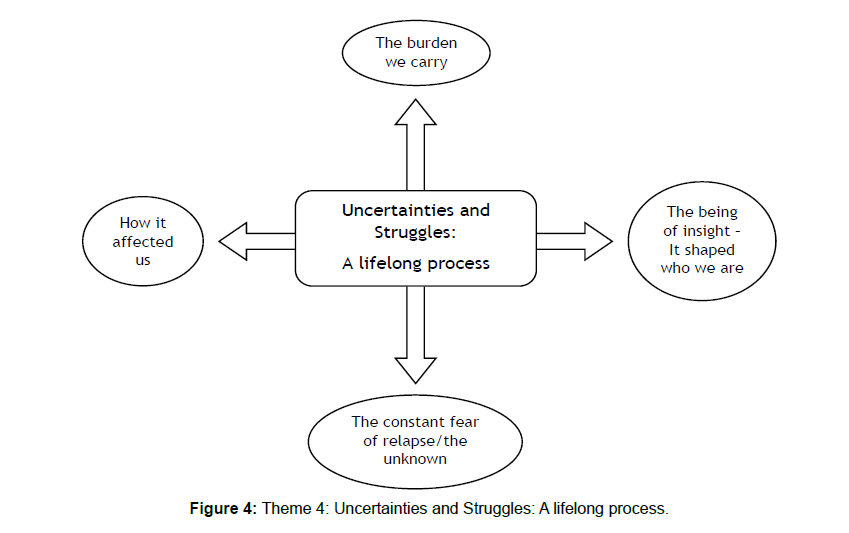

Theme 4 Uncertainties and struggles: A life-long process

This theme describes how the phenomenon of addiction is experienced by family members; the burden of care. Here, caregivers described the uncertainties and struggles involved in caring for a relative with substance abuse problems. This experience may be described as a life-long process. Lived experience of the human phenomenon of addiction thereby becomes a process where the fear of the unknown, blame etc. all become an embodiment of the future, insights and meanings leading to personal growth. Four features emerged from this theme; how it affected us, the burden we carry, the being of insightit has shaped who we are, and the constant fear of relapse/unknown (Figure 4).

How it affected us: The effects of substance abuse on the caregiver became more pronounced on how the self-struggled to relate to the other. Time may have been spent on the substance-abusing relative thereby ignoring the needs of family caregivers. Furthermore, when a child is involved in the caregiving experience, the effects of the phenomenon of addiction became evident in their growth and development.

“from the time I was in kindergarten I can remember getting up, making myself a cup of coffee, and getting myself off to school by making a peanut butter sandwich, putting it in a bag and getting myself dressed in the same clothes that I wore every single day, because I didn't have a parent getting myself ready for school. So for a lot of years I think I struggled with that and, and grieved the way that I grew up.”

The burden we carry: Caregivers reported an ongoing burden as it relates to the needs of their relative. In other instances, relatives became completely dependent on the caregiver for all financial support as they may not be able to be financially independent due to their drug use. The burden of financial support was noted to be a major stressor. This was a need that caregivers may have to constantly revisit. A participant stated;

And now we're in a position where we know he’s struggling, and financially struggling, and we’ve made a decision that we are not going to do that, that he has to face the consequences of his actions and he’s got to do this himself. It is not the first time. But every other time we have kind of gone back and forth. We'd say, “We're not doing this anymore.” And then we'd get sucked in and we'd help him a little bit.”

The being of insight-It shaped who we are: The uncertainties and struggles family caregivers went through as they provided care for their relatives with alcohol and or opiate problems led to insightful meanings. In this case, caregiver burden as an experience became a self-transformational process.

“So I think that’s one of the things it did for my life, is to teach me patience. So I learned that I never would judge someone with an addiction as poor character, because I know from my own husband. He didn't have poor character. He was a hard worker, he was helpful, he was caring, and you just had to remember when he’d had too much to drink, that’s not really him. I grew a lot because I learned that alcoholism is not a choice that people fall into it for various reasons. And then from his experience in Vietnam, which gave him a lot of demons that he was trying to make peace with.”

The constant fear of relapse /unknown: Due to the chronic nature of addiction, there was the fear of the unknown. Caregivers were usually consumed in the “what if’s” of an undesirable event. The constant fear of relapse became more evident in the notion of addiction as a chronic relapsing disease. Addiction became a disease that caregivers always had to consciously bring into awareness.

“So if the phone rings at an odd time, or sometimes just when I see her name come up on my phone, I get anxious because I’m not sure if it’s going to be a good thing or a negative thing. So it definitely puts an emotional strain on, on me. That’s an immediate panic, because I worry about overdose all the time. So it kind of always made you feel like you were living on the edge and waiting for the next shoe to drop.”

Discussion and Implications

The philosophical tenets of van Manen’s phenomenology of practice provided an underlying framework in understanding the family caregiver burden of a relative with alcohol and/or opiate abuse problems; the moment caregivers learned of a relative’s substance abuse problems, and the acceptance, decision making and support that follow. The four main themes identified in this study support the methods of guided existential inquiry of lived relation (relationality), lived time (temporality), Lived space (spatiality), lived material things, and lived body (corporeality) as proposed by van Manen.

Lived relationality describes “how the self and others are experienced with respect to the phenomenon that is being studied” [14]. The relationship between the self and the other depicts an experiential moment. Fundamentally, the phenomenon of living with a relative with addiction problems becomes a relational experience. Here, the self struggles to accept the existence of such a problem. Extension of the self is perpetuated by the sacrifice and dedication that ensued in the moment of the experience.

Acceptance becomes a temporality (lived time). Being, as a construct has been described by [30] as time. Time thereby becomes a fluid in which being occurs. The being of acceptance is perpetuated by becoming aware (awareness) and Telos. Telos is described by van Manen [14] as the “wishes, plans and goals we strive for in life” (p. 306). Telos becomes a goal-oriented purpose, an ultimate end. Becoming aware of a family member’s addictive behaviors is very devastating. Here, caregivers place themselves in two worlds (spatiality-lived space); a world of shattered dreams and that of future expectations as in seeing the caregiving role as a failure. Acceptance thereby vindicates itself in the “womb” of time. Acceptance as a “being” of reality is an “enduring” process. Insight, a precursor to acceptance comes in a moment and is subject to the test of time.

A phenomenon is experienced in relation to “things” (lived material things). This experience of a “thing” has a direct impact on the self. As van Manen [14] claimed “Thus, in our encounter with the things, we experience the moral forces they exert on and in our lives” (p. 307). Of note, “how are things experienced and how do the experience of things lead to insightful meanings of phenomenon” [14]. The healthcare experience thereby becomes a thing that cannot be separated from the self. It becomes an extension of the self and mind. The disrespect and resentment faced by caregivers as they encounter the healthcare system becomes a thing that is being kept. Experience becomes personal or strange. The experience of a thing (health care system) should lead to insightful meanings. These insightful meanings are translated into terminology that reflects positive connotations (“relapse and sobriety” not “clean and dirty”) consistent with current research trends of addiction as a disease.

Corporeality-Lived Body depicts how the phenomenon is experienced in relation to the body or self. This body corporeality or embodiment is regarded by some phenomenologists as the motif fundamental to the understanding of human phenomenon [14]. In the human phenomenon of addiction, the whole body is involved in the uncertainties and struggles as this becomes a life-long process for the family caregiver. This object/subject experience of the body as it relates to the human phenomenon of addiction shows how people experience the same phenomenon differently, which van Manen [14] describes as the singularity of experience.

Findings and prior empirical Literature: Two interrelated major findings relating to the family caregiver burden of addiction emerged from the four main themes. These are caregiver burden of guilt and stigma, and addiction as a disease. These are;

Caregiver burden of guilt and stigma: Guilt and stigma are the defining characteristics that distinguish addiction from other chronic illnesses. This study builds on existing knowledge of the role stigma plays in the acceptance process. Stigma as a multi-faceted construct [31], is seen as a subjective burden. It has been reported that stigma against substance abusers is one of the main barriers to treatment delivery, and public health outcomes [32,33]. Kessler, McGonagle, Zhao, Nelson, Hughes, Eshleman [34] claimed that, due to the comorbidity of substance abuse disorder with other psychiatric disorders, substance abuse stigma is one component of psychiatric disorders stigmatization. Further, it has been asserted by Rasinki, Woll & Cooke [35] and Room [36] that public attitudes expressed towards substance abusers differ from those with mental illness. To buffer this claim, Barry, McGinty, Pescosolido, & Goldman [37], Parcesepe & Cabassa [38] and Link, Struening, Rahav, Phelan & Nuttbrock [39] reported that, individuals with substance abuse problems are likely to be more stigmatized than individuals with mental illness. This is due to societal view of addiction as a moral failure or personal choice rather than a disease. Van Boekel, Brouwers, Van Weeghel & Garretsen [40] reported that healthcare professionals also had negative attitudes towards persons with substance abuse. One thing that was clear was the impact stigma had on the caregiving experience by heightening the burden of care.

Stigmatization may prevent early identification and treatment [41], leading to an increase in the burden of care. As Usher et al [10] reported, the realization of the existence of the phenomenon of addiction in the family member is compounded by doubt until the exhibition of certain behaviors which apparently confirm a substance abuse problem. Here, family caregivers make conscious efforts to keep it as a secret for fear of societal stigma. Participants also reported that stigma was a hindrance in the acceptance process. All these coupled with caregivers’ self-blame for being the cause of relative’s substance abuse problems heightened the burden of care.

Addiction as a disease: There has been increasing evidence for the past two decades that addiction, is a disease of the brain [42]. Addiction as reported by participants in this study is known as the “hidden disease”; a disease that has negative social connotations or seen as a moral failure. The concept of addiction as a disease continues to raise societal questions [42]. It is important to note that, conceptualizing addiction as a disease has provided the evidence for cutting-edge treatment interventions, preventive measures and viable public policy [42]. Addiction as a chronic relapsing disease provides insight into the burden of care. Burden reported in this study is ongoing and it ranges from financial support to other critical needs. Financial support being the most reported burden is consistent with prior literature findings. Family caregivers spent a significant portion of their income and time directly on relative abusing substances [25]. In providing financial support, participants reported unknowingly supporting the relative’s drug use.

Implication for Practice: Participants provided several insightful recommendations for assisting family caregivers. These recommendations seek to enhance healthcare providers’ understanding of family needs and the caregiver’s burden. Findings of this study suggest that caregiver needs including support may be different at each stage of the caregiving experience. This finding is consistent with Raymond’s (2016) qualitative descriptive study of Parents Caring for Adults with Serious Mental Illness. During the initial stages of the experience, caregivers’ encounter with the healthcare system and their needs are usually focused on support and nurturing. Focusing the initial healthcare experience on providing information about the disease and treatment process is necessary in decreasing the guilt and pain associated with the burden. Further, caregivers reported utilizing the healthcare system, especially through the emergency room, as the first point in accessing care. Having a dedicated specialized addiction service team as a centralized referral center is needed in addressing needs of caregivers and their relatives. A continuum of care with a variety of integrated supportive and ancillary services that address the multiple needs of this population may improve their chances of recovery and their quality of life [13].

The Role of the 12-Step programs in addiction treatment and services cannot be underscored enough. Participants reported meeting places as dilapidated; meetings being held in back rooms, basements and not the nicest places. Dignified meeting places are needed. These 12-Step programs need to be incorporated into the medical field as with other support groups. It is critical to dignify addiction just like any other disease and afford respect to those affected, both substance abusers and especially family caregivers. Participants reported the need for a change in terminology that reflects addiction as a disease such as “remission” and “exacerbation” and refraining from negative connotation such as “clean” and “dirty”.

The recent crisis in opiate overdose requires an integrated approach involving family caregivers. This approach includes educating caregivers about this crisis and life saving measures. Additionally, there is a need to educate substance abusers about the importance of family support in achieving and maintaining sobriety.

Implication for research

Support is an important concept in the caregiving role as it relates to substance abuse. Racial and cultural/ethnic differences in the support family caregivers provide for their relative with substance abuse problems require further inquiry. Exploring these differences as to how support is conceptualized, identifying the nature of support, and needs of family caregivers at various stages of the experience are areas deserving further investigation. Also, studies focusing on how stigma is conceptualized among family caregivers of relatives with substance abuse problems are needed. Such studies should focus on identifying strategies to increase public awareness of addiction as a disease, decrease stigma and enhance the acceptance process.

Implications for health policy

A recent surge in drug overdoses has provided a window of opportunity in bringing public awareness of the extent of substance abuse and the burden of care. Awareness may reduce stigma and guilt thereby enhancing the acceptance process. Building coalitions to increase awareness of substance abuse and the burden of care with mental health advocates and other stakeholders such as AARP, NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness), AL-Anon Family Group, Family Caregiver Alliance etc., is important. Due to the scope and nature of this problem, addressing it at the local level offers many advantages. At the local level, increasing awareness may be addressed through the involvement of key community stakeholders. Local campaigns with more modest goals are more effective and likely to achieve positive results [43]. Providing awareness includes but is not limited to providing public education on the societal forces, genetic susceptibility and environmental factors that influence substance abuse and its impact on families.

Policies to increase access to healthcare for substance abuse and related services are important. These policies should consider a comprehensive approach to care. Integration of primary care and behavioral care may improve access to care, treatment and overall effective management of substance abuse as a disease [42,44]. These policies may make available resources for family caregivers.

The shortage of addiction specialists, other ancillary staff and treatment beds are barriers to efficient and effective treatment. Policies to arouse interest in this specialty including expansion of student loan forgiveness programs with the aim of increasing staff to bridge the gap in treatment. Also, most caregivers reported access to information regarding their relative in treatment as problematic due to privacy laws [45,46]. In order to encourage caregivers to be active participants in their relatives’ care and assume advocacy role, privacy reforms are necessary.

Limitations

Participants recruited for this study reside in a large urban area and were of limited racial or ethnic backgrounds. Experiential materials that were gathered might not be similar to other ethnic or racial groups in rural areas or other geographic areas. The study demographics do not reflect the gender and ethnic differences in family caregiving and how burden and support are conceptualized among other population groups.

Moreover, the researcher needed to avoid emotional distress for participants and avoided exploring some of the deeper meanings as it would have caused additional emotional burden. A strength of this study was the use of van Manen’s method to uncover the eidetic meaning of the human phenomenon of addiction from the perspectives of family caregivers: the moment caregivers learned of a relative’s addiction problems, acceptance and nature of support, and the decision-making processes that follow thereafter as they seek to care for their relative.

Conclusion

This research study explored a very sensitive topic as it relates to the caregiver burden of substance abuse. Participants shared some of their deepest experiences devoid of any theoretical or suppositional inclinations. Despite these private feelings of the phenomenon of substance abuse, participants expressed the importance of sharing their stories to increase societal awareness of substance abuse and the burden of care, and to provide a framework for conceptualizing addiction as a disease. Knowledge gained from this study supports the need to design clinical interventions which are multidimensional for effective caregiver assessment, strategies to offset this burden, increase family involvement and supportive services to prevent relapse and sustain sobriety.

References

- https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf

- Rospenda KM, Minich LM, Lauren MA, Milner MS, Richman JA. (2010) Caregiver Burden and Alcohol Use in a Community Sample. J Addict Dis 29(3):314-324.

- Family Caregiver Alliance (2007). Family Caregiving: state of the art, future trends. Report From a national conference. San Francisco, California.

- McCann TV, Lubman DI. (2012) Primary caregivers’ satisfaction with clinicians’ response to them as informal carers of young people with first-episode psychosis: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 21(1-2):224-31.

- Ari Houser, Mary Jo Gobson. (2011) Public Institute. Valuing the invaluable: The economic value of family caregiving.

- Zegwaard MI, Aartsen MJ, Cuijpers P, Grypdonck MH. (2011) Review: A Conceptual Model of perceived burden of informal caregivers for older persons with severe Functional psychiatric syndrome and concomitant problematic behavior. J Clin Nurs 20:2233-2258

- Vaingankar JA, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vincent YF He, Chong SA. (2012) “How Much Can I take?†Predictors of Perceived Burden for Relatives of People with Chronic Illness. Ann Acad Med Singapore 41(5):212-20.

- Manneli P. (2013) The burden of caring: Drug users and their families. Indian J Med Res 137(4):636-638.

- Usher, K, Jackson, D, & O’Brien, L. (2007). Shattered dreams: Parental experiences of adolescent substance abuse. Int J Ment Health Nurs 16:422-430.

- Peterson J. (2010) A qualitative comparison of parent and adolescent views regarding substance Use. J Sch Nurs 26(1):53-64.

- Â DÃaz C JB, Brands B, Adlaf E, Giesbrecht N, Simich L, et al. (2009) Drug consumption and treatment from a family and friends perspectives. Guatemala. Rev Latin America Enfermagem 17:824-30.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2010). Results from the 2010 NSDUH summary of findings.

- Van Manen M (2014). Phenomenology of Practice: Meaning-Giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing. Left Coast Press, CA.

- Francine CD, Louise LL, Lise ML, Marie-Jeanne K, Alain JL. (2011) Learning to become a family caregiver: Efficacy of intervention program for caregivers following diagnosis of dementia. Gerontologist 51(4):484-494.

- Manson MJ. (2011) Mental health, school problems and social networks: modeling urban Adolescents’ substance use. J Prim Prev 31:321–331.

- Torvik FA, Rognmo K, Ask H, Roysamb E, Tambs K. (2011) Parental alcohol use and Adolescent school adjustment in the general population: results from the HUNT Study. BMC Public Health 11:706.

- Rachel NL, Arthur HMS. (2015) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2013). The CBHSQ Report. Trends in heroin use in the United States.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (2008). Addiction Science: From Molecules to Managed Care.

- Weitzenkakmp DD, Gerhart KA, Charlifue MW, Whiteneck GG, Savic G. (1997) Spouses of spinal cord injury survivors: the added impact of caregiving. Arch Phys Medical Rehabil 78: 822-827.

- Salize JH, Jacke C, Kief S, Franz M, Manni K. (2012) Treating alcoholism reduces Financial burden on care-givers and increases quality-adjusted life years. Addiction 108(1):62-70.

- Marcon SR, Rubira EA, Espinosa MM, Barbosa DA. (2012) Quality of Life and Depressive Symptoms among caregivers and drug dependent people. Rev Latino American Enfermagem, 20(1):167-174.

- Biegel DE, Saltzman KS, Meeks D, Brown S, Tracy EM. (2010) Predictors of depressive symptomatology in family caregivers of women with substance use disorders or cooccurring substance use and mental disorders. J Fam Soc Work 13(2):25–44

- Sales E. (2003) Family burden and quality of life. Qual Life 12(Suppl 1):33-41.

- Clark RE. (1994) Family Costs Associated With Severe Mental Illness and Substance Use. Hosp Commu Psyc 45(8):808-813.

- Brown S, Lewis V. (2002) The alcoholic family in recovery: A developmental model. New York: Guilford Press.

- Bogdan RC, Bilken SK. (1992) Qualitative research for education: An introduction to a Theory and Methods. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Sandelowski M. (1995) Focus on Qualitative Methods. Sample Size in Qualitative Research. Res Nurs Health 18:179-183.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. (2008) Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (8th ed.). New York, NY: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott

- Heidegger M. (1962) Being and time (J Macquarrie & E Robinson, Trans). New York, NY: Harper & Row (Original work published 1927).

- Sercu C, Bracke P. (2016) Stigma as a Structural Power in Mental Health Care Reform: An Ethnographic Study among Mental Health Care Professionals in Belgium. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 30(6):710-716.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1999) Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health.

- Birtel MD, Wood L, Kempa NJ. (2017) Stigma and social support in substance abuse: Implications for mental. Psychiatry Res 252:1-8.

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, et al. (1994) Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51:8−19.

- Rasinki KA, Woll P, Cooke A. (2005) Stigma and substance disorders. In P. W. Corrigan (Ed.), On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change (pp. 219−236). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Room R. (2005) Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev 24(2):143-55.

- Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, Goldman HH. (2014) Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: Public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatry Serv. 65:1269–1272.

- Parcesepe AM, Cabassa LJ. (2013) Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: a systematic literature review. Adm Policy Mental Health 40:384–399.

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock, L. (1997). On stigma and its consequences: Evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of al illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav 38:177−190.

- Van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, Van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. (2013) Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 131:23–35.

- Ahern, J, Stuber, J, Galea, S. (2007). Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88, 188-196Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (2016). Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N Engl J Med 374:363-371.

- Freudenberg N, Bradley SP, Serrano M. (2009) Public health campaigns to change industry practices that damage health: An analysis of 12 case studies. Health Educ Behav 20:1-20.

- Saitz R, Jo Larson M, LaBelle C, Richardson J, Samet JH. (2008). The case for chronic Disease management for addiction. J Addict Med 2(2):55-65.

Citation: Duah A (2020) Lived Experience of Caregivers of Relatives with Alcohol and Opiate Dependence (A phenomenological study). J Addict Res Ther 11:395. DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000395

Copyright: © 2020 Duah A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2014

- [From(publication date): 0-2020 - Jul 17, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1408

- PDF downloads: 606