Research Article Open Access

Lessons Learn by Peace Officers Working In Mental Health Collaboratives

D’Andre Lampkin

National University, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- E-mail: dandrelampkin@gmail.com

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

The purpose of this research project is the introduce readers to the experiences of peace officers assigned to field teams that investigate incidents involving mental illness and the lessons learned throughout the evaluation process. This paper also endeavors to expose readers to how law enforcement agencies across the United States are addressing mental illness and improving response to incidents involving subjects with mental illnesses. Also included are highlights focused on training and the collaborations taking place between mental health professionals and law enforcement agencies wanting to combine judicial supervision with community based mental health treatment.

Introduction

How law enforcement agencies approach calls for service involving violent individuals, suicidal persons, and suspicious persons has changed. In recent years, police departments across the nation are being criticized for how they treat the mentally ill in and out of the custodial environment. Much debate has been made about whether law enforcement agencies bare any responsibility for the force used against the mentally ill who react abnormally toward police and the public. Critics question whether policies should incorporate an assessment for mental illness prior to taking lawful action and address the high number of prisoners diagnosed with a mental health disorder. Such was the case with the recent use of force incident involving Ezell Ford and the Los Angeles Police Department (“Ezell Ford: The mentally ill black man killed by the LAPD two days after Michael Brown’s death” 2014). How are law enforcement’s efforts to address mental illness changing the path to incarceration? What steps are law enforcement agencies taking to address the needs of the mentally ill? What are some of the challenges to responding to calls for service involving the mentally ill? What responsibilities do law enforcement agencies have to insure the mentally ill are getting the treatment they need?

Findings

According to Watson, psychiatrist of Jane Addams College of Social Work and Angel, lead psychiatrist of the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research at Rutgers State University of New Jersey, law enforcement has always played a pivotal role in addressing problems involving the mentally ill, especially in poor communities. Approximately 1% of those identified as mentally ill come from poor communities. Research has concluded that, “on average, 10% of [law enforcement] contacts with the public involve persons with mental illness.” However, this is not to suggest the likelihood of developing a mental health disorder is related to living in a poor community. While it may appear that a majority of mentally ill persons come from a low social class, these individuals end up in poor communities after a series of occupational failures due to their developing mental illness which lead to a downward spiral toward unskilled jobs. The series of events that lead to the downward spiral is referred as the Down Drift Phenomena. Contact with the mentally ill has increased as more outpatient and inpatient psychiatric clinics are releasing patients into the community. Often times community demand the need for more mental health treatment facilities but often times are opposed to having them built in their own community. As a result, the facilities are built and operated in communities with lower participation in city government and hearings where the decision about what will be built in a city is decided.

The way in which the police contact the mentally ill determine whether the encounter will result in violence, significant use of force, or a peaceful resolution. Handling calls involving the mentally ill are problematic and it is nearly impossible to predict whether or not a police officer will encounter someone who is mentally ill when responding to calls for service but the likelihood is inevitable and officers must be prepared for such encounters.

In order to understand the challenges law enforcement officers face when contact members of the community with mental illness or individuals experiencing a mental health crisis, we must first understand the nature of mental illness and its symptoms. While there is widespread consensus among scientist that individuals suffering from mental disorders carry a genetic predisposition, it is still unclear whether environmental factors also trigger these disorders. Current theorists posit mental illness is hereditary and has the ability to skip around between generations, meaning, mental illness is not linear. For example, symptoms of mental illness seen in a grandmother can later reappear in the grandchild without presenting itself in the child’s mother or father. Mental illness can also skip from one cousin to another. To understand this concept in a more simple way, take for example the flipping of a coin. If you flip a coin, the chance of the coin landing on heads or tails is 50%. Even if you flipped the coin 10 times, the chances of the coin landing on heads or tails is still 50%, even if the coin landed on heads 8 of the 10 times. (J. Zada MD, personal communication, October 10, 2015). Sometimes the existence of a mental illness will be prevalent in one member of the family, all members of the family, or none.

In a publication titled, Missing Gene: Psychiatry, Heredity, and the Fruitless Search for Genes, the author Joseph Jay summarizes his research in pellagra twin and adoption studies. In his research he argues that family, twin, and adoption based studies are inherently biased and lack foundation.

To understand Joseph’s reasoning, one must take into consideration family and twin studies conducted in the 1920’s to find the cause of pellagra. Pellagra is a deficiency disease caused by a lack of nicotinic acid. It was originally thought that pellagra was hereditary since at least one parent had been diagnosed with having the condition, which is characterized by mental disturbances along with other symptoms. In summary, scientist initially attempted to prove their theory by adopting out twins who already came from broken homes. Children were more likely to be paired with families of similar income status. It wasn’t until scientist realized that the eating habits in the new homes were similar to the homes the child came from that they abandoned the idea of genetic predisposition and began to look at the environment as a cause. But let’s suppose scientist at the time proved their initial hereditary theory and the pellagra epidemic continued to grow. Pallagra would still be a problem today while scientists continue to focus on the environmental trigger versus looking at the diet of those suffering from the condition.

In an effort to prepare law enforcement for encounters with the mentally ill, agencies are requiring officers to undergo comprehensive training. Clinical Coordinator of Behavioral Health at St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, Jeanine Loucks, discusses the training of law enforcement as it relates to mental illness. Loucks, who spends time outside of the hospital teaching law enforcement across the country about how to effectively interact with people dealing with mental illness, posits many law enforcement officers receive basic training on how to deal with the mentally ill during their time in the academy. The program she has developed provides law enforcement with additional training about psychological disorders and how they affect individuals. She stresses that, interventions, awareness of services, and effective communication skills with members of the community afflicted with mental illness is critical to a successful outcome.

Law enforcement officer’s response should still be tactical in nature. Upon receiving the call, officers should review the information that is already known in an attempt to understand what type of emergency they are responding to and take into consideration whether or not the call involves someone who is potentially experiencing a mental health crisis. Witness accounts like, “person is acting bizarre”, “disturbing party is nude in street”, or “a homeless person” could yield clues about what is happening. Dispatchers and supervisors can help in the pre-planning phase by insuring that at least two officers are assigned to the call. Not only does it ensure greater strength in the event the encounter becomes physical, but two officers provide greater options and alternate viewpoints for deescalating the crisis.

Responding to calls related to mental health crisis occurring in a residence can prove to be especially complicated. It is likely the officer assigned to the call has never been in the home and is unaware if weapons are available and accessible. Prior to the officer’s arrival, 9-1-1 dispatchers can assist by getting as much information from the caller about the individual as possible. Prior to officers approaching the residence, officers should attempt to contact the informant to ascertain what behaviors the disturbing party is exhibiting and what may be triggering them. Assess the person before approaching. Does the disturbing party appear homeless, talking to themselves (reacting to an internal stimuli), or fixated on another person or object? Are they malodorous, tangential when they speak, or lacking a sense of moral conduct like exposing their sex organs without appearing to be concerned about privacy? Sometimes a quick assessment can tell officers what additional resources they may need to bring the situation to a safe conclusion.

It is important for officers to have a plan. One strategy to reducing the likelihood of confusion and deescalating the disturbing party is to assign one officer to do all of the talking to the disturbing party. The other officers should remain quiet as their uniformed presence is already speaking volumes. Everyone involved should also understand that resolving the crisis is a team effort. No independent action should be taken without the knowledge of every officer involved in the investigation. Also, try to avoid direct eye contact for long periods of time as it might be perceived as a challenge for the individual experiencing the mental health crisis. But, at the same time, be aware of the individual’s movements.

Most mental health professionals and law enforcement executives agree that a vast majority of homeless, especially those in large urban areas, face mental health disorders. In situations where the person having a mental health crisis appears to be homeless, officers should be aware, if not expect, the person to have some type of weapon. A homeless person who is mentally ill is three times more likely to be a victim of a crime than any ordinary citizen. According to Katherine B. O’Keefe, author of “Protecting the Homeless Under Vulnerable Victim Setencing Guidelines: An Alternative in hate crime laws.”, the homeless are more likely to feel like they are being treated as second-class citizens. They are avoided on the street, exploited in social media videos, and victims of extreme violence.

An example of such violence occurred in July 2015. New Mexico Huffington Post Reporter, Michael McLaughlin, told the story of a homeless man who had fireworkds thrown at him as he slept. The homeless man nearly died from his injuries. Surveillance video lead to the capture of the suspects who committed the violent act and subsequent interview revealed the husband and wife couple “were just playing around.” In the same report Michael mentions that two other homeless people in Albuquerque had been subject to extreme violence within close time periods. One homeless man was brutally beaten by teens and had cinder blocks thrown at him in July while another had been intentionally ran over by a motorist in June. Typically weapons carries by homeless people are used for self-protection. It is important to note that crime is higher among the general population, or those perceived as “normal”, than among the mentally ill community.

There are a wide variety of mental health disorders law enforcement officers may see during calls where a mental health crisis is taking place. The most common is depression. Some of the symptoms officer may look for are sadness, depressed, or irritable mood. The informant may express that the person showing signs of depression has had a loss of appetite, overreacts to small problems, has not been sleeping, has difficulty concentrating, gained or loss as significant amount of weigh, or expresses suicidal ideations. In these situations, the potential for a suicide by cop scenario is the highest. The person who is depressed may feel hopeless and have a desire to end their life in a way that requires the least amount of effort and culpability on their part.

Another mental health disorder commonly seen by law enforcement is the bipolar disorder. Approximately 5.8 million American adults or about 2.4% of the population ages 18 or older in any given year exhibit bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder typically develops in late adolescence or early adulthood. Often times, bipolar disorder is misdiagnosed by mental health and medical professionals. Manic episodes, a common symptom of bipolar disorder, increase in people as they get older. Bipolar disorder is a chronic illness much like diabetes or heart disease that must be carefully managed throughout the person’s life.

Because law enforcement officer’s primary task is to enforce the law, it is not uncommon for them to mistake symptoms of mania for symptoms of controlled substance abuse. In fact, it is also difficult for medical staff to differentiate between substance induced mania psychosis or mental illness. For example, an officer conducts a pedestrian stop of a person who is exhibiting racing thoughts and rapid speech. The disturbing party jumps from one idea to another and appears to be distracted with an inability to concentrate. We will explore more about how treatments can also mimic abnormal behavior later in the paper. Officers are now being trained to consider if the person is experiencing a manic episode. People undergoing a manic episode may appear to have an increase in energy or activity and restlessness. People experiencing mania are likely unpredictable. They may also have grandiose believes in their ability or power and a decreased need for sleep. Alcohol and drug abuse are very common among people with bipolar disorder. Approximately 82%

of individuals known to have bipolar disorder are also known to abuse drugs and alcohol. They tend to self-medicate and their mood is often triggered by substance abuse. The key to treating bipolar disorder is compliance with their psychiatrist orders and follow-through with their prescription medication regiment.

There are several strategies officers can use to dealing with people experiencing a manic episode. To start, decrease noise and confusion in the area when possible. Remove other people from the area. Ask the disturbing party short and direct questions and be patient. Officer may notice the person is pacing continuously. Sometimes pacing is necessary to maintain focus and should be allowed if it is safe to do so.

Schizophrenia is another mental disorder officers are most likely to see while performing their daily responsibilities. In the United States, approximately 2.6 million adults or about 1.1% of the population ages 18 and older in a given year have been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Current hypothesis about suggest that schizophrenia is genetic, however, a connection has also been found with abnormalities in how the brain functions. Most cases of schizophrenia come to light between the ages of 17 to 25 in men and ages 25 to 35 in women. Women have a higher chance of successfully managing and recovering from schizophrenia since by the age of 25 they tend to be more educated, have established a family, and are more stable in both their personal and professional life.

Symptoms of schizophrenia are quite apparent to the objectively reasonable officer. People who are facing a mental health crisis involving schizophrenia tend to be delusional. In other words, they have fixed false beliefs that are not grounded in reality. Hallucinations are also a common occurrence. Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia sense perceptions that do not exist in the real world. Hallucinations can occur in the sensory, auditory, and visual form. Auditory hallucinations, or the ability to hear voices that no one else can hear, are the most common types of hallucinations experienced by those facing a schizophrenic crisis. The most common symptom of schizophrenia is poor insight. Meaning, if you were to ask 95% of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia about the treatment they are receiving, they would state they are not receiving treatment for their mental illness. To explain even more simpler, if you were to ask why they were taking pills, they would state they don’t know why they are taking their medication.

Command hallucinations warrant special concern. When it comes to paranoid delusions, persecutory delusions are most common. When the delusions occur, the disturbing party tends to believe people, or groups of people, are conspiring against them. It’s is not uncommon for them to believe that entities like the Central Intelligence Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigations, or local law enforcement is out targeting them. They may also insinuate that they are being poisoned. Hearing voices that no one else can hear is also a common symptom. People diagnosed with schizophrenia may state they are being told by someone to hurt themselves or hurt other people. The voices they hear are always persecutory, meaning they are negative and demanding hallucinations. The voice have been said to be male or female sounding and it is common that a person diagnosed with schizophrenia will report multiple voices are having a conversation about the individual.

It is highly likely law enforcement officers could come in contact with individuals as they are medicated and released back into the community. Members of the community who face mental illness are treated with varying medications to help them cope with their condition. Common medications include antipsychotic, mode stabilizers, and antidepressants.

Antipsychotic medications are used to stop voices, fixed or false beliefs, and delusions. These types of medications can improve memory as they makes it easier for the patient to focus, study for exams, remember numbers, or remember how to perform common problem solving techniques. Side effects include drowsiness, dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, decreased sexual drive, stiff muscles on the side of the neck or mouth, tremors, restlessness, shuffled walking, and muscle spasms.

Mood stabilizers could cause a mental health patient to appear as though they are having seizures when violent shaking occurs. However, contrary to the symptoms being presented, most mood stabilizers are anti-seizure medications. In my experience as a member of a mental evaluation team, people who are contacted by law enforcement in high desert areas and are prescribed lithium often complain of feeling dehydrated and have a desire to remove their clothing after exposure to the outdoors for long periods of time. Symptoms of mood disorders can diminish 5 to 14 days after treatment begins but could take several months before the condition is fully controlled. Some side effects of mood stabilizers include drowsiness, weakness, nausea, hand tremors, skin rashes, double vision, anxiety, confusion, and suicidal thoughts. People who are stabilized with medication are less suicidal.

Over 30 percent of woman and men prescribed antidepressant medications complained of sexual complication and an inability to reach an orgasm climax. Some of the side effects that an officer may witness or hear a person facing a mental health crisis complain of include headaches, nausea, sleeplessness or drowsiness, agitation or a feeling of jitters, reduced sex drive, dry mouth, constipation, short term blurred vision, and suicidal ideation.

While most would agree that careful consideration should be given to the mentally ill when resolving issues, a successful outcome also means enforcing the law fairly. This is especially important in instances where there is a clear violation of the law and detention or arrest is necessary. A team of mental health administrators conducted a study in 1997 to determine the outcomes of contact with law enforcement with the mental ill. The subjects used in the study were engaged in ongoing treatment by an Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) program. Approximately 100 ACT clients were studied. Researchers collected data on arrest and other outcomes of contacts with law enforcement and found that a majority had some contact with law enforcement. The mental health administrator’s research concluded that most individuals being treated by mental health professionals and who also had contact with law enforcement were arrested for infraction offenses.

Individuals who most frequently had contact with law enforcement also tended to be undergoing more extensive mental health treatment. The research conducted by the consortium of mental health professionals supports the idea that law enforcement has more frequent contact with individuals who require intensive mental health treatment. Additionally, individuals with more severe mental health issues are more likely to have their offenses documented by law enforcement via citation or release after accurate identification in lieu of long term detention in a jail facility pending the appearance before a magistrate.

As demands for law enforcement to reassess how they approach mental illness grows and mental health department budgets decrease, agencies are consolidating resources to insure consistency and sharing best practices. Michael Klein, Chief of Sand City California Police Department discusses in an FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin efforts of law enforcement to combine resources to create a standardized training program which endeavors to better address mental health crisis situations. The article acknowledges law enforcement is the first to respond to incidents that potentially involve individuals who are mentally ill. The Monterey County California Police Chiefs Association decided the best method to dealing with this growing reality was to combine their services, develop mutual aid agreements, and create a standardized program to train law enforcement officers on how to deal with the mentally ill, and seek out resources offered by the mental health community. Included in a footnote of the article, “The Memphis, Tennessee, Police Department established this mental health emergency response model that couples intense crisis intervention training for officers with a partnership between law enforcement agencies, mental health providers, advocates, and individuals who are mentally ill.” The footnote also adds “many law enforcement agencies throughout the country have adopted this model.”

Law Enforcement agencies like the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and Los Angeles Police Department have established teams that combine police officers, advocates, and licensed clinicians from the Department of Mental Health. Examples include the Mental Evaluation Team (MET), Psychiatric Mobile Response Teams (PMRT), and System-wide Mental Assessment Response Team (SMART). They vary by name, but nationally they are all most commonly called Crisis Intervention Teams or “CIT”. For example, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Mental Evaluation Team responds to incidents where regular patrol deputies have identified a person to be a danger to themselves, danger to others, or gravely disable. The specially trained deputy sheriff along with a clinician from the Department of Mental Health conduct an assessment of the subject and determine whether they need to be placed on a 72 hour hold in a psychiatric facility based on the criteria given. Rather than arrest the subject for a minor infraction or misdemeanor offense, the mental health specialist may also escort the subject to a mental health facility, outpatient psychological services, homeless shelter, or return them to the care of a provider. The team also specializes in deescalating potentially violent encounters and tension between uniform police officers and persons experiencing a mental health crisis. Patrol officers call upon the assistance of these types of teams to reduce the risk of using physical force or intermediate weapons to gain compliance or, worse, deadly force.

States like Florida, Alaska, and Indiana are using Mental Health Courts in an effort to couple judicial supervision with community mental health treatment. The courts also link other support services such as housing placement and substance abuse treatment in an effort to reduce criminal activity and elevate the quality of life of its participants. A group of administrators from the Administration of Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research discuss the nomenclature of Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT), the purpose of CIT, expected outcomes, and changes in how the mentally ill interact with CIT-trained officers. The study focused on self-efficacy and social distancing between the mentally ill and law enforcement. Law enforcement’s interactions with four major groups were included in the study. The groups included those suffering from depression, cocaine dependence, schizophrenia, and alcohol dependence. What the study found was that individuals in these four groups were more likely to reduce social distance. The study also revealed that, while further research in officer-level outcomes may need to be conducted, members of the four groups were more likely to interact with emergency services when they needed help versus allowing their behavior to evolve to criminal misconduct and subsequent incarceration.

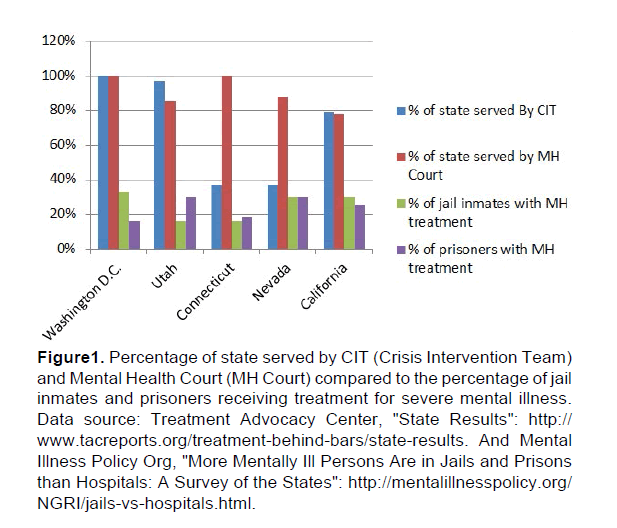

Below is a sample comparison of states that fund Crisis Intervention Teams and Mental Health Courts and how much of the state is served by the teams and the courts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of state served by CIT (Crisis Intervention Team) and Mental Health Court (MH Court) compared to the percentage of jail inmates and prisoners receiving treatment for severe mental illness. Data source: Treatment Advocacy Center, "State Results": http://www.tacreports.org/treatment-behind-bars/state-results. And Mental Illness Policy Org, "More Mentally Ill Persons Are in Jails and Prisons than Hospitals: A Survey of the States": http://mentalillnesspolicy.org/NGRI/jails-vs-hospitals.html.

The data comes from statistics gathered between the years of 2005 and 2013 and de

rive from two sources. The Treatment Advocacy Center advocates for the restoration of psychiatric treatment centers in the United States. The organization focuses on making recommendations for policy makers that steer the mentally ill away from jail and prisons and into mental health treatment facilities. Mental Illness Policy Org was founded by DJ Jaffe, former board member of NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness). It should be noted that the graph presents the most recent data available. Much of the topic has never been explored in depth. It is important to take into account the information's historical relevance when examining the findings. Crisis Intervention Teams and Mental Health Courts are fairly new. It is also important to take into account inconsistences in law enforcement research and reporting requirements. Law enforcement agencies voluntarily provide certain statistics to federal agencies. Despite short term research, preliminary results suggest that the use of CIT and Mental Health Courts, proportionately, vary from state to state. However, the data does support the idea that law enforcement agencies efforts to invest in and expand Crisis Intervention Teams are a priority. The interdisciplinary approach enables law enforcement agencies to divert low level offenders facing mental illness away from the jail and prison system and into community-based treatment facilities.

Conclusion

It is clear encounters with the mentally ill are unavoidable. Proper training is imperative to insuring a successful outcome. Through collaborative partnerships with advocates in the mental health community, comprehensive training, and knowledge-based field assessments, law enforcement agencies across the United States can quell concerns over how law enforcement approaches incidents involving the mentally ill and reduce the number of encounters resolved by use of physical or deadly force.

References

- Bahora, M., Hanafi, S., Chien, V.H., &amli; Comliton, M.T. (2008). lireliminary Evidence of Effects of Crisis Intervention Team Training and Self-Efficacy and Social Distance. Administration of liolicy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(3), 159-167.

- Johnson, T (2014). Ezell Ford: The mentally ill black man killed by the LAliD two days after Michael Brown’s death. The Washington liost. Retrieved from: httli://www.washingtonliost.com/news/morning-mix/wli/2014/08/15/ezell-ford-the-mentally-ill-black-man-killed-by-the-lalid-two-days-after-michael-browns-death/

- Joselih, J (2005). Missing Gene : lisychiatry, Heredity, and the Fruitless Search for Genes. New York, NY, USA: Algora liublishing. liroQuest ebrary. Web. 2 October 2015.

- Klein, M. (2002). FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 71(2), 11-14.

- Loucks, J.S. (2013). Educating Law Enforcement Officers about Mental Illness: Nurses as Teachers. Journal of lisychosocial Nursing &amli; Mental Health Services, 51(7), 39-45. McLaughlin, M (2015)." Sleeliing Homeless Man Set On Fire With Fireworks" Huffington liost.Huffington liost,21 July. 2015. Web.1 Oct. 2015.

- O'Keefe, K.B. (2010). lirotecting the homeless under vulnerable victim sentencing guidelines: An alternative to inclusion in hate crime laws.William and Mary Law Review,52(1), 301.

- Watson, A.C. &amli; Angell, B (2007) Alililying lirocedural Justice Theory to Law Enforcement’s Reslionse to liersons With Mental Illness, lisychiatric Services, 58(6), 787-793.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 10507

- [From(publication date):

December-2015 - Jul 05, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9565

- PDF downloads : 942