Knowledge about Palliative Care and Patient Portal Utilization among Adults with Chronic Disease

Received: 03-Mar-2023 / Manuscript No. JCPHN-23-90814 / Editor assigned: 06-Mar-2023 / PreQC No. JCPHN-23-90814(PQ) / Reviewed: 20-Mar-2023 / QC No. JCPHN-23-90814 / Revised: 22-Mar-2023 / Manuscript No. JCPHN-23-90814(R) / Accepted Date: 22-Mar-2023 / Published Date: 29-Mar-2023 DOI: 10.4172/2471-9846.1000393 QI No. / JCPHN-23-90814

Abstract

Objective: To examine the knowledge, perceptions, and predictors of palliative care among American adults with chronic disease using nationally representative data.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 1,506 respondents (≥ 18 years old) with at least one chronic disease from the cycle 2 of the 2018 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). The respondents selfreported level of knowledge about palliative care and patient portal utilization were pooled to preform descriptive and logistic regression analyses using Stata 17.0.

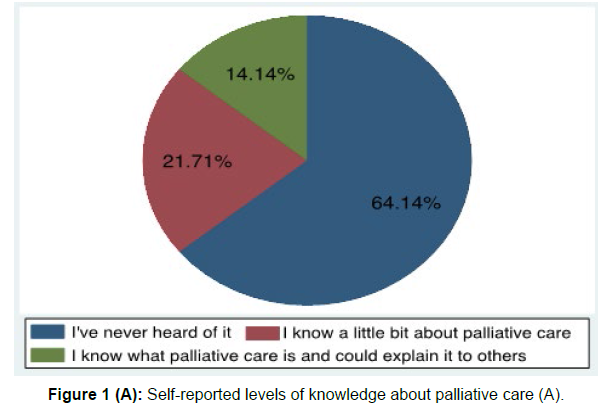

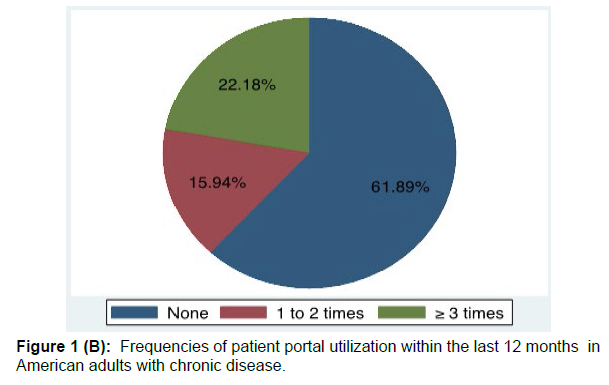

Results: Overall, 64.14% of American adults with chronic illness had never heard of palliative care and 61.89% of them did not utilize patient portals. Among those who reported knowledgeable about palliative care, 31.3% of them thought that palliative care was the same as hospice, 38.88% of them linked palliative care to death automatically. Respondents who utilized patient portals more than three times a year were 34% (p = .033) more likely to report knowledgeable about palliative care than nonusers of patient portals.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates significant low-level of knowledge about palliative care among people with chronic disease. Given the positive association between patient portal utilization and health literacy about palliative care, healthcare professionals should educate and empower patients to use patient portals which may help enhance the knowledge about palliative care and thereby utilization of palliative care in this population.

Keywords

Patient portal; Palliative care; Chronic disease; Personal health records; Electronic health records

Introduction

Approximately 60% of American adults live with chronic disease (e.g., heart disease, cancer, and diabetes) which is the leading cause of death and disability in the United States [1]. Palliative care (a specialty care to manage physiological and psychosocial needs associated with serious illness [2] has been shown to decrease symptom burden and increase quality of life for patients with chronic and deliberating illnesses, [3–6] to improve satisfaction for both patients and caregivers, and to enhance attention of healthcare providers on symptom management [7].Despite these benefits, the rate of palliative care utilization remains low. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that only about 14% of people who need palliative care have received it worldwide. Such a low utilization rate is contributable to the lack of public knowledge and misconceptions about palliative care [8- 11]. Among the US general population, only 12.6% reported knowing palliative care well and were able to explain it to others, [12-14] and the knowledge level of palliative care was even lower in patients with low socioeconomic status and certain vulnerable populations [15] To date, there are limited studies targeting American adults with chronic disease and investigating their knowledge level of palliative care and the predictors of improved knowledge in palliative care.

Studies have shown that healthcare utilization is associated with the level of awareness about palliative care [16]. Recently found that those who visited healthcare professionals more than two times per year were three times as likely to know about palliative care. Patient portals, or personal health records, are secure websites that provide patients the access to their personal health information and health care services [17] Through these portals, patients can share and track medical information with providers [18,19] and participate in decision making about their advance care planning [20] According to the selfdetermination theory of learning [21] people who access and utilize the portals frequently tend to be autonomous and are intrinsically motivated in learning of health literacy. Although patient portals have been made available and free to patients over the past decade, a substantial proportion of patients still reported not utilizing these online records [22, 23] which could potentially contribute to the lack of awareness and knowledge about palliative care. However, it is unknown whether there is an association between patient portal utilization and the level of knowledge about palliative care.

Therefore, the purposes of this study were 1) to provide data on the level of knowledge about palliative care among American adults with chronic disease; and 2) to examine our hypothesis that patient portal utilization would be positively associated with the level of knowledge about palliative care among American adults living with chronic disease.

Methods

Sample

We used data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 5, Cycle 2, 2018, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of non-institutionalized U.S. adults aged 18 years or older and administrated by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Briefly, this data collection cycle was conducted from January 2018 to May 2018 (HINTS, 2018) and was the only cycle of survey with added question on palliative care. More details can be found in the corresponding methodology reports and our previous study. [24,25] Respondents (N = 2,427) who self-reported at least one of the following conditions were included in this study: depression, diabetes, heart condition, hypertension, lung disease, cancer, and arthritis. We excluded respondents who had missing data, resulting in a sample of 1,506. Respondents who self-reported that they knew a little bit or very well about palliative care were included for second step analysis to evaluate their misconceptions and attitudes toward palliative care.

Measures

Knowledge of palliative care

The dependent variable was the level of knowledge about palliative care. To measure the knowledge of palliative care, participants were asked “How would you describe your level of knowledge about palliative care?” Responses were categorized into three groups as “I have never heard of it”, “I know a little bit about palliative care”, and “I know what palliative care is and could explain it to others.” To evaluate respondents’ understanding about palliative care, those who reported to be knowledgeable about palliative care (“I know a little bit about palliative care” and “I know what palliative care is and could explain it to others”) were further assessed with the following statements: the goals of palliative care were to (a) help friends and family to cope with a patient’s illness; (b) offer social and emotional support; (c) manage pain and other physical symptoms; and (d) give patients more time at the end of life. The following statements were used to evaluate their attitudes toward palliative care: (i) accepting palliative care means giving up; (ii) if you accept palliative care, you must stop other treatments; (iii) palliative care is the same as hospice care; and (iv) when I think of “palliative care,” I automatically think of death. A Likert Scale was used to group the responses into five categories: (1) strongly agree, (2) somewhat agree, (3) somewhat disagree, (4) strongly disagree, and (5) don’t know.

Predictors and covariates

The key predictor was the patient portal utilization by respondents. To measure patient portal utilization, participants were asked the following two questions: “Have you ever been offered online access to your medical records by your health care provider or health insurer?” (1 = Yes, 2 = No, 3 = Don’t know) and “How many times did you access your online medical record in the last 12 months?” (None, 1, 2, 3, 4, or ≥ 5). Responses were further grouped into three categories based on above two questions due to small sample size in some of the subgroups: “none” indicating in the last 12 months that participants were either never offered patient portal access or were offered but did not utilize the portal; “1-2 times” indicating that participants accessed their patient portal 1 to 2 times, and “≥ 3 times” indicating that participants accessed their online medical records 3 times or more.

The following covariates were included in this study based on previous studies: [8,12,13,26] age, sex (male or female), education level (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, bachelor’s degree, and post-baccalaureate degree), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other), marital status (married or not married), family history of cancer (yes or no), selfreported general health (good or poor), caregiving role (yes or no), chronic disease burden (1, 2 or ≥3), body mass index (BMI), annual household income ranges (< US$19,999, US$20,000 to US$49,999, US$50,000 to US$74,999, US$75,000 to US$99,999, US$100,000 to US$199,000, and US$200,000 or more), and smoking status (former, current, and never smoker).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted to describe the characteristics of the respondents. Ordered logistic regression was used to assess the association between the level of knowledge about palliative care and patient portal utilization after the adjustment of covariates and odds ratios (ORs) were reported. We performed several statistical tests (e.g., Omodel test, Brant test) in addition to traditional visual inspection to ensure that ordered logistic regression assumptions were met in modeling the level of knowledge about palliative care. There was no multicollinearity issue between independent variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all regression tests were two-tailed. The above analyses were conducted using Stata 17.0.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the respondents included in the regression analyses (N = 1,506). The majority of respondents were middle-aged and older, were female, had education higher than high school graduate, identified as non-Hispanic white, were married, were non-smokers, had a family history of cancer, had only one chronic disease, were not a caregiver, were employed, reported good general health, and were overweight/obese. (Table 1)

| Characteristics | Sample (N = 1,506) |

|---|---|

| Chronic diseases burden | |

| 1, n (%) | 616 (40.9%) |

| 2, n (%) | 470 (31.21%) |

| ≥3, n (%) | 420 (27.89%) |

| Age, M (SD) | 58.43 (15.75) |

| Sex | |

| Male, n (%) | 649 (43.09%) |

| Female, n (%) | 857 (56.91%) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school, n (%) | 92 (6.11%) |

| High school graduate | 238 (15.8%) |

| Some college, n (%) | 465 (30.88%) |

| Bachelor’s degree, n (%) | 404 (26.83%) |

| Post-baccalaureate degree, n (%) | 307 (20.38%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 1,023 (67.93%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black, n (%) | 187 (12.42%) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 186 (12.35%) |

| Other, n (%) | 110 (7.30%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married, n (%) | 809 (53.72%) |

| Not married, n (%) | 697 (46.28%) |

| Household income | |

| $0 to $19,999, n (%) | 202 (13.41%) |

| $20,000 to $49,999, n (%) | 429 (28.49%) |

| $50,000 to $74,999, n (%) | 319 (21.18%) |

| $75,000 to $99,999, n (%) | 188 (12.48%) |

| $100,000 to $199,999, n (%) | 260 (17.26%) |

| $200,000 or more, n (%) | 108 (7.17%) |

| Smoking Status | |

| Never, n (%) | 893 (59.3%) |

| Former, n (%) | 422 (28.02%) |

| Current, n (%) | 191 (12.68%) |

| Family history of cancer | |

| Yes, n (%) | 1,126 (74.77%) |

| No, n (%) | 290 (19.26%) |

| Don’t know, n (%) | 90 (5.98%) |

| Self-reported general health | |

| Good, n (%) | 1,289 (85.59%) |

| Poor, n (%) | 217 (14.41%) |

| Caregiving role | |

| Yes, n (%) | 200 (13.28%) |

| No, n (%) | 1,306 (86.72%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed, n (%) | 875 (58.1%) |

| Not employed, n (%) | 631 (41.90%) |

| Body mass index, M (SD) | 29.14 (6.58) |

Table 1: Characteristics of Study Sample.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of respondents by the level of knowledge about palliative care and frequency of patient portal utilization in adults with chronic disease. Of the 1,506 respondents, 932 (61.89%) did not use patient portals within the last 12 months, 996 (64.14%) had never heard of palliative care. In total, 540 (35.86%) respondents (327 knew a little bit and 213 knew palliative care very well and were able to explain it to others) self-reported as knowledgeable about palliative care. (Figure 1)

Table 2 provides the frequencies and percentages of the perceived goals and perception of palliative care among individuals (N = 540) who reported knowing a little bit or very well about palliative care. Most participants strongly agreed that the perceived goals of palliative care were to manage pain and other physical symptoms (77.04%), to offer social and emotional support (62.22%), and to help friends and family cope with a patient’s illness (53.52%). However, the misconception of palliative care was commonly seen in the following statements: 31.3% of the respondents who either strongly agreed or somewhat agreed that “palliative care was the same as hospice” and 38.88% of the respondents who either strongly agreed or somewhat agreed that “when I think of palliative care, I automatically think of death”. (Table 2)

| Strongly agree | Somewhat | Don’t know | Somewhat disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | agree | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| N (%) | |||||

| Perceived goals of palliative care | |||||

| Help friends and family to cope with a patient’s illness | 289 (53.52) | 188 (34.81) | 27 (5) | 21 (3.89) | 15 (2.78) |

| Manage pain and other physical symptoms | 416 (77.04) | 90 (16.66) | 23 (4.26) | 9 (1.67) | 2 (.37) |

| Give patients more time at the end of life | 175 (32.41) | 135 (25) | 45 (8.33) | 105 (19.44) | 80 (14.82) |

| Offer social and emotional support | 336 (62.22) | 165 (30.56) | 21 (3.89) | 11 (2.04) | 7 (1.29) |

| Perception of palliative care | |||||

| Palliative care is the same as hospice | 42 (7.78) | 127 (23.52) | 95 (17.59) | 117 (21.67) | 159 (29.44) |

| Accepting palliative care means giving up | 10 (1.85) | 60 (11.11) | 17 (3.15) | 117 (21.67) | 336 (62.22) |

| If you accept palliative care, you must stop other treatments | 18 (3.33) | 57 (10.56) | 83 | 124 (22.96) | 258 (47.78) |

| -15.37 | |||||

| When I think of “palliative care”, I automatically think of death | 49 (9.07) | 161 (29.81) | 28 (5.19) | 135 (25) | 167 (30.93) |

Table 2: Frequencies and percentages of the perceived goals and perception of palliative care in adults with chronic diseases (N = 540).

Table 3 presents the results from ordered logistic regression comparing the odds of knowing about palliative care among adults with chronic disease with and without patient portal utilization. This model was significant, χ2 = 268.49, df = 14, p < .001. Frequent patient portal users (≥3 times per year) were 34% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.76, p = .033) more likely to report being knowledgeable about palliative care, controlling for covariates. Compared with adults with a less than high school education, those who had some college, bachelor’s degree, or post-baccalaureate degree were 2.92 (95% CI, 1.38-6.19, p = .005), 4.18 (95% CI, 1.94-8.97, p < .001), and 7.24 (95% CI, 3.32-15.76, p < .001) times more likely to report knowledge about palliative care, respectively. Females and caregivers were 2.57 (95% CI, 2.02-3.27, p < .001) and 1.48 (95% CI, 1.09-2.02, p = .012) times more likely to know palliative care than males and non-caregivers. Compared with non- Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic participants were 51% (95% CI, .33-.72, p < .001) and 40% (95% CI, .41-.89, p = .01) less likely to know palliative care, respectively. (Table 3)

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 | 0.1 | 1.02 | 0.22 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 (reference) | |||

| Female | 2.57 | 2.02 | 3.27 | <.001 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 1 (reference) | |||

| High school graduate | 1.63 | 0.74 | 3.58 | 0.221 |

| Some college | 2.92 | 1.38 | 6.19 | 0.005 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4.18 | 1.94 | 8.97 | <.001 |

| Post-baccalaureate degree | 7.24 | 3.32 | 15.76 | <.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 (reference) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.72 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.6 | 0.41 | 0.89 | 0.01 |

| Other | 0.79 | 0.5 | 1.22 | 0.287 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 (reference) | |||

| Not married | 1.15 | 0.89 | 1.48 | 0.278 |

| Household income | ||||

| $0 to $19,999 | 1 (reference) | |||

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 1.18 | 0.77 | 1.81 | 0.44 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 1.17 | 0.74 | 1.86 | 0.501 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 1.35 | 0.81 | 2.24 | 0.253 |

| $100,000 to $199,999 | 1.62 | 0.98 | 2.67 | 0.059 |

| $200,000 or more | 2.25 | 1.23 | 4.11 | 0.008 |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Never | 1 (reference) | |||

| Former | 1.38 | 1.07 | 1.78 | 0.015 |

| Current | 1.11 | 0.77 | 1.6 | 0.572 |

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| Yes | 1 (reference) | |||

| No | 0.77 | 0.57 | 1.03 | 0.08 |

| Not sure | 0.74 | 0.44 | 1.25 | 0.263 |

| Self-reported health | ||||

| Good | 1 (reference) | |||

| Poor | 0.75 | 0.53 | 1.07 | 0.113 |

| Caregiving role | ||||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 1.48 | 1.09 | 2.02 | 0.012 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 1 (reference) | |||

| Not employed | 0.84 | 0.62 | 1.14 | 0.27 |

| Body mass index | 1 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.676 |

| Chronic diseases burden | ||||

| 1 | 1 (reference) | |||

| 2 | 1.16 | 0.88 | 1.52 | 0.287 |

| ≥3 | 1.16 | 0.85 | 1.58 | 0.354 |

| Medical records utilization | ||||

| None | 1 (reference) | |||

| 1-2 times | 1.2 | 0.89 | 1.63 | 0.236 |

| ≥3 times | 1.34 | 1.02 | 1.76 | 0.033 |

Table 3: Ordered Logistic Regression Predicting the odds of knowledge about Palliative Care among American Adults with Chronic disease (N = 1,506).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the knowledge level of palliative care and patient portal utilization in American adults with chronic disease. We demonstrated that over 60% of American adults with chronic disease did not know about palliative care and did not use patient portals. We further found that patient portal utilization was a predictor of the level of knowledge about palliative care in American adults with chronic disease, after adjusting for covariates: those who utilized patient portals more frequently were more likely to be knowledgeable about palliative care. Our novel findings provide clinical implications in increasing palliative care utilization via patient portals.

In this nationally representative sample of American adults with chronic disease, about two-thirds had never heard of palliative care which is comparable with previous reports. Previous studies found that 66% of cancer survivors [13] and 71% of the general population [14] had never heard of palliative care. Only less than 30% of American adults were knowledgeable about palliative care [8, 27]. Even among those who reported to be knowledgeable about palliative care, misconceptions were common, which was consistent with the previous findings [12, 13, and 27]. We found that about half of American adults with chronic disease thought palliative care was linked to death or hospice. Given the negative perceptions of hospice and death, some healthcare professionals found using alternative terms (e.g., supportive care) in their palliative care program helped avoid such confusion [28].

The internet is one of the major sources of knowledge and information regarding palliative care [13, 15]. Utilization of patient portals can not only allow patients to track their own health information shared by providers, but also provide patients an environment to learn health literacy, such as palliative care. While patient portal utilization can benefit people with chronic disease in many ways, most adults living with chronic disease (61.89%) in this study reported that they either had no access to or had not utilized the patient portals within the last 12 months. Barriers to patient portal utilization are multifactorial. Many vendors offered stand-alone electronic patient portals, which presented the greatest environmental barrier to integrated personal health medical records utilization [19]. Additionally, the users must understand the importance of maintaining health-related documentations and be able to communicate with healthcare providers [19]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that patient portal utilization was a predictor of the level of knowledge about palliative care in American adults with chronic disease: those who utilized patient portals more frequently were more likely to be knowledgeable about palliative care, thereby utilizing it when needed. In addition, of the covariates, education and being a caregiver were positively associated with an improved level of knowledge about palliative care, and those participants who identified as non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic were less likely to know about palliative care. These findings of health disparities were consistent with previous studies [8, 12].

This study demonstrated significant practice implications for healthcare professionals. It is imperative for healthcare professionals to be aware of the low level of knowledge about palliative care among adults living with chronic disease as well as some potential disparities of care and knowledge among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic participants[29]. When discussing palliative care or initiating referrals to palliative care services, healthcare professionals should evaluate patients’ knowledge and ensure full understanding of the service provided. They should also take the time to acknowledge and address these potential disparities in care to help patients receive needed palliative care. Given the positive association between patient portal utilization and improved health literacy about palliative care, healthcare professionals need to ensure adequate time is taken to educate patients on the importance of and how to access online medical records while working with adult patients living with chronic disease.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The self-reported awareness of palliative care and patient portal utilization were subject to recall bias, which could underestimate or overestimate the association. The crosssectional design of this study prevented us from evaluating respondents’ long term disease burden and the need of palliative care. Additionally, the data for this study was collected prior to the COVID pandemic which had resulted in a significant increase in the use of telehealth, digital health care and widespread media coverage of associated topics including palliative care. These events have the potential to increase baseline knowledge of palliative care that had not previously been demonstrated in the literature. Further studies using validated tools to assess the level of knowledge about palliative care and the evidence of patient portal utilization are recommended.

Implications for public health nursing

This study demonstrates significant implications for public health nursing practice due to the significant reported low-level of knowledge about palliative care among people living with chronic disease. According to the WHO, adults with chronic disease in need of palliative care will continue to grow as the population ages. Limited awareness and misconceptions might be significant barriers to palliative care uptake in this group of people. As patient advocates, public health nurses should work with other healthcare workers and policy makers to develop programs and provide palliative care education for people in need of this service. Given the health and knowledge disparities and inequities noted in the literature and this study, it is also essential to target these public health initiatives to our vulnerable populations so they may better access these critical resources.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that American adults with chronic disease have an extremely low level of knowledge and possess many misconceptions about palliative care. Given the positive association between patient portal utilization and the level of knowledge about palliative care, encouraging patients to use their patient portals may help enhance the knowledge about palliative care and thereby utilization of palliative care in this population. This study also highlights the existence of a health disparity among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic participants in awareness of palliative care. These findings suggest that educational efforts and solutions at all levels including policy makers, educators, and healthcare professionals are warranted to improve palliative care knowledge in people living with chronic disease, especially for those vulnerable and disadvantaged minority population.

References

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/whats-new-in-infectious-diseases

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

- Carpenter JG, McDarby M, Smith D, Johnson M, Thorpe J, et al. (2017) Associations between Timing of Palliative Care Consults and Family Evaluation of Care for Veterans Who Die in a Hospice/Palliative Care Unit. J Palliat Med 20:745-751.

- Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D (2016) Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 316: 2104-2114.

- Murali KP, Yu G, Merriman JD, Vorderstrasse A, Kelley AS, et al. (2021) Multiple Chronic Conditions among Seriously Ill Adults Receiving Palliative Care. West J Nurs Res 45:14-24.

- Quinn KL, Shurrab M, Gitau K (2020) Association of Receipt of Palliative Care Interventions With Health Care Use, Quality of Life, and Symptom Burden Among Adults With Chronic Non cancer Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA324: 1439-1450.

- Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Sjøgren P (2020) Exploratory analyses of the Danish Palliative Care Trial (DanPaCT): a randomized trial of early specialized palliative care plus standard care versus standard care in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 28: 2145-2155.

- Adjei Boakye E, Mohammed KA, Osazuwa-Peters N (2020) Palliative care knowledge, information sources, and beliefs: Results of a national survey of adults in the USA. Palliat Support Care 18:285-292.

- Cai Y, Lalani N (2022) Examining Barriers and Facilitators to Palliative Care Access in Rural Areas: A Scoping Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 39: 123-130.

- Parajuli J, Hupcey JE (2021) A Systematic Review on Barriers to Palliative Care in Oncology. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 38: 1361-1377.

- Vaughn L, Santos Salas A (2022) Barriers and facilitators in the provision of palliative care in critical care: A qualitative descriptive study of nurses’ perspectives. Can J Crit Care Nurs 33: 14-20.

- Flieger SP, Chui K, Koch-Weser S (2020) Lack of Awareness and Common Misconceptions About Palliative Care Among Adults: Insights from a National Survey. J Gen Intern Med 35:2059-2064.

- Stal J, Nelson MB, Mobley EM (2022) Palliative care among adult cancer survivors: Knowledge, attitudes, and correlates. Palliat Support Care 20: 342-347.

- Trivedi N, Peterson EB, Ellis EM, Ferrer RA, Kent EE (2019) Awareness of Palliative Care among a Nationally Representative Sample of US Adults. J Palliat Med 22:1578-1582.

- Cheng BT, Hauser JM (2019) Adult palliative care in the USA: information-seeking behaviour patterns. BMJ Support Palliat Care.

- Ogunsanya ME, Goetzinger EA, Owopetu OF, Chandler PD, O’Connor LE (2021) Predictors of palliative care knowledge: Findings from the Health Information National Trends Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol 30:1433-1439.

- Ingle MP, Valdovinos C, Ford KL (2021) Patient Portals to Support Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res 23.

- Bush RA, Pérez A, Baum T, Etland C, Connelly CD (2018) A systematic review of the use of the electronic health record for patient identification, communication, and clinical support in palliative care. JAMIA Open 1:294-303.

- Tang PC, Black W, Buchanan J (2003) PAMF Online: Integrating Health with an Electronic Medical Record System. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003: 644-648.

- Portz JD, Brungardt A, Shanbhag P (2020) Advance Care Planning Among Users of a Patient Portal During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Observational Study. J Med Internet Res 22.

- Cook DA, Artino Jr AR (2016) Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories. Med Educ 50: 997-1014.

- Earnest MA, Ross SE, Wittevrongel L, Moore LA, Lin CT (2004) Use of a Patient-Accessible Electronic Medical Record in a Practice for Congestive Heart Failure: Patient and Physician Experiences. J Am Med Inform Assoc 11:410-417.

- Khan S, Lewis-Thames MW, Han Y, Fuzzell L, Langston ME, et al. (2020) A Comparative Analysis of Online Medical Record Utilization and Perception by Cancer Survivorship. Med Care 58: 1075-1081.

- Liu Z, Wang J (2022) Associations of perceived role of exercise in cancer prevention with physical activity and sedentary behavior in older adults. Geriatr Nur (Lond 44: 199-205.

- https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/methodologyreports/HINTS5_Cycle_2_Methodology_Report.pdf

- Huo J, Hong YR, Grewal R (2019) Knowledge of Palliative Care Among American Adults: 2018 Health Information National Trends Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 58: 39-47.

- Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Kozlov E, Shen MJ, Adelman RD (2018) Awareness and Misperceptions of Hospice and Palliative Care: A Population-Based Survey Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35:431-439.

- Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL (2009) Supportive versus palliative care: What’s in a name? Cancer 115: 2013-2021.

- Meier DE, Back AL, Berman A, Block SD, Corrigan JM (2017) A National Strategy For Palliative Care. Health Aff Millwood 36: 1265-1273.

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Inada N (2023) Knowledge about Palliative Care and Patient Portal Utilization among Adults with Chronic Disease . J Comm Pub Health Nursing, 9: 393. DOI: 10.4172/2471-9846.1000393

Copyright: © 2023 Inada N. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2948

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Dec 08, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2527

- PDF downloads: 421