Isolated Sphenoid Inflammatory Diseases

Received: 02-Jul-2018 / Accepted Date: 08-Aug-2018 / Published Date: 15-Aug-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000357

Abstract

Background: Isolated sphenoid inflammatory disease is a rare clinical condition among patients with paranasal sinus disease, reported incidence ranged between 1%-3%. The most common symptoms of isolated sphenoid inflammatory lesions are headache, ophthalmological and nasal symptoms. Delayed diagnosis may occur due to its nonspecific symptoms. The disease requires appropriate and good imaging technique for diagnosis. Objective: To discuss different pathologies of isolated sphenoid inflammatory lesions. Patients and Methods: From 2008 to 2017, we performed surgery on 27 patients with isolated sphenoid inflammatory diseases. The presenting signs and symptoms, radiological studies, operative findings and clinical outcomes were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed. Results: 27 cases were identified at tertiary hospital of King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam; 12 bacterial sphenoid sinusitis, 4 allergic fungal sinusitis, 4 fungal balls, 2 invasive fungal sinusitis, 3 pediatric (2 sphenoid sinusitis and 1 allergic fungal sinusitis), 1 mucocele and 1 mycopyocele. Conclusion: Isolated sphenoid inflammatory disease is rare, with comprehensive history taking, complete physical examination, appropriate endoscopic examination and advanced imaging studies will give appropriate clinical diagnosis. Histopathology and microbiology are important for definite diagnosis.

Keywords: Sphenoid sinus; Bacterial sinusitis; Fungal sinusitis; Fungal ball; Mucocele

Introduction

Isolated sphenoid inflammatory lesions are relatively rare and as a result of their nonspecific clinical presentation, they are difficult to diagnose at first presentation [1]. The sphenoid sinuses are located at the skull base at the junction of the anterior and middle cerebral fossae and they begins to grow between the 3rd and 4th months of fetal development. Pneumatization of the sphenoid bone starts at three years old and reaches its final shape in the mid-teens [2,3]. The anatomic position of sphenoid sinus is bounded superiorly the sella turcica, laterally the sphenoid sinus can have important prominences including the carotid canal and the optic canal: In the cavernous sinus, the most medial structure is the internal carotid artery.

The symptoms and signs of the patients with isolated sphenoid inflammatory disorders are nonspecific. However, the most common presenting symptom is the headache, representing around 80% of cases [4-6]. Twelve percent of the presenting symptoms include vision problems and problems due to involvement of other cranial nerves [7]. The imaging studies are essential in the diagnosis of isolated sphenoid lesions. Computerized Tomography (CT) scan is the gold standard tool for the diagnosis as it may show different pathologies and assist in differentiation between neoplasm from inflammatory disease and fungal from bacterial infections. Magnetic Resonant Imaging (MRI) is used if there is a suspicion of extension to the CNS (Central Nervous System) or the orbit.

Patients and Methods

A retrospective study of all patients diagnosed with isolated sphenoid inflammatory diseases at a tertiary hospital of King Fahad specialist hospital Dammam, KSA from 2008 to 2017 was done. The presenting signs and symptoms, radiological studies, operative findings and clinical outcomes were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed and full description of some selected cases are presented in this report. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at our institution.

Results

Twenty seven cases were studied at tertiary hospital of King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam; 12 (44.4%) bacterial sphenoid sinusitis, 4 (14.8%) allergic fungal sinusitis, 4 (14.8%) fungal balls, 2 invasive fungal sinusitis, 3 pediatric (2 sphenoid sinusitis and 1 allergic fungal sinusitis), 1 mucocele and 1 mycopyocele (Table 1).

| Pathologies of Isolated Sphenoid Inflammatory Disease | Number of Cases | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Sphenoid sinusitis (acute/chronic) | 12 | 44.4 |

| Allergic Fungal Sinusitis (AFS) | 4 | 14.8 |

| Fungal ball | 4 | 14.8 |

| Invasive fungal sinusitis | 2 | 7.4 |

| Pediatric: 2 sphenoid sinusitis, 1 AFS | 3 | 11.1 |

| Mucocele, Mucopyocele | 2 | 7.4 |

| Total | 27 | 100 |

Table 1: Pathology of cases of isolated sphenoid inflammatory diseases, King Fahad specialist hospital, Dammam, Saudi Arabia (2008-2017).

Discussion

Pathologies of isolated sphenoid inflammatory disease

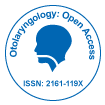

Bacterial sphenoid rhinosinusitis: Bacterial Sphenoid Rhinosinusitis was the most common isolated sphenoid inflammatory lesion, occurring in 12 patients of our series. The commonest pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, aerobic gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes [8-12]. These patients presented with headache, rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction and blurred vision. The most common presenting symptom of sphenoid sinus disease was mainly headache. In the majority of previous reports, headache was non-specific in site, intensity as well as quality [13]. Physical examination and endoscopic finding of cases may show mucopurulent secretion at the spheno-ethmoidal area, edema of the spheno-ethmoidal recess mucosa and polypoid tissue in the spheno-ethmoidal recess. The CT scan of the sinuses shows opacification in the sphenoid sinus, with thickening in the mucosal wall and air-fluid level (Figure 1). Management of patients with bacterial Sphenoid Rhinosinusitis is mainly medical treatment with antibiotic based on culture and sensitivity in addition to topical decongestant and corticosteroid. The surgical management (endoscopic sphenoidotomy) was applied only in case of failure of medical treatment or if patient presented with complications (Figure 2).

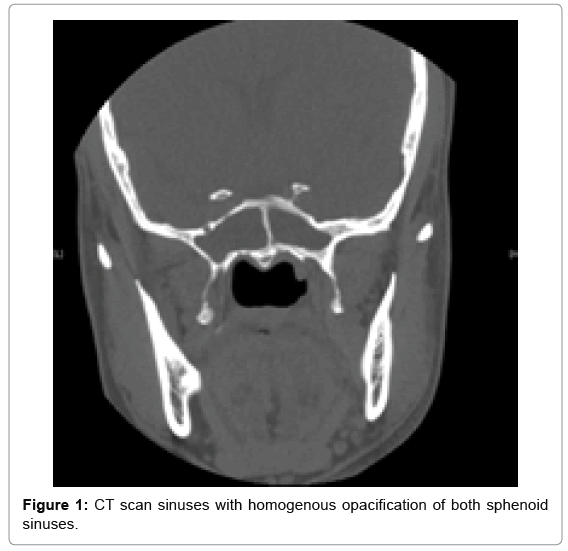

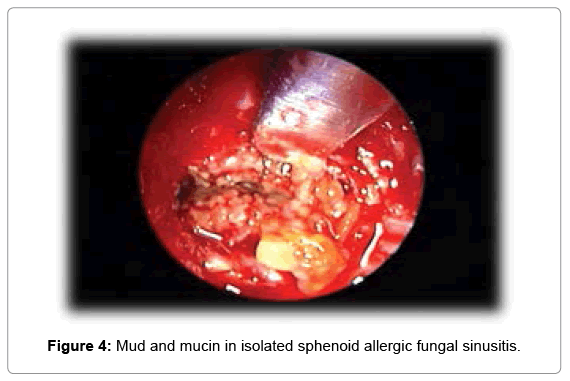

Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis AFS: Allergic fungal sinusitis is reported among 4 cases in our series. It is a non-invasive fungal sinusitis usually found in immune-competent patients with a strong inflammatory response to the fungal infection. This commonly results in a thick mucin that may cause bony decalcification. Additionally, there marked bone resorption and mucosal thickening as a result of the secretion of enzymes. Endoscopic examinations of these patients showed the presence of polyps and allergic mucin. Diagnosis of cases were based on Bent and Kuhnheir diagnostic criteria which depend on the disease characteristics from histologic, radiographic and immunologic features including type 1 hypersensitivity, the presence of nasal polyposis, characteristic CT findings of heterogeneous hyperdensities that are often unilateral and asymmetric as shown in one of our cases (Figure 3), positive fungal stain or culture and an eosinophilic mucin [14]. AFS can easily compress the cranial nerves. It had been documented that cranial neuropathies occur in 10% of cases of AFS with bone erosion [15]. Treatment of AFS includes endoscopic sphenoidotomy to clear polyps and allergic mucin as shown in Figure 4 and to improve the ventilation and drainage of sinuses through addition of corticosteroids. Histopathology is pathognomonic as it shows allergic mucin containing fungal components without any tissue invasion. Post-operataively, immunotherapy might be beneficial.

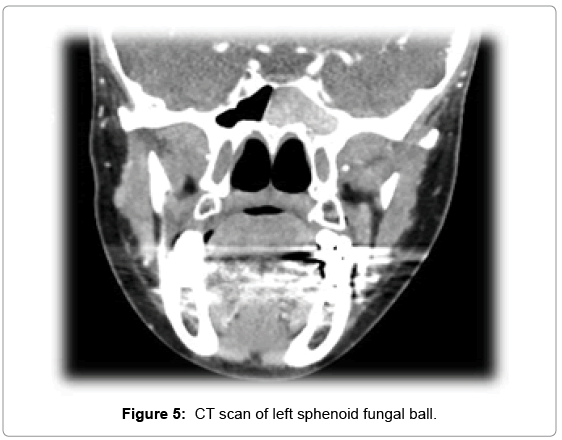

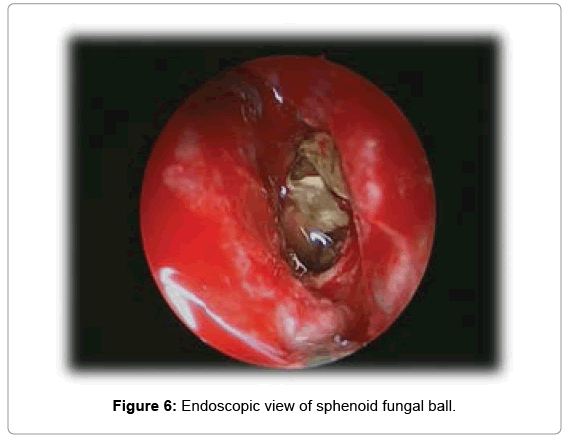

Fungal ball: Also, our series of cases includes 4 cases of fungal ball. It is a non-invasive fungal infections, involves mostly maxillary sinus. Internationally, it represents nearly 10% of chronic non-invasive fungal sinusitis. The primary causative organism is Aspergillus. Clinically it is characterized by non-specific symptoms such as headache, which is the commonest symptom, followed by purulent rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction. The gold standard technique for its diagnosis is CT scan. Figure 5 shows CT findings of one of our series. Fungal ball appears as hyper-attenuating in CT due to dense hyphae with evidence of chronic inflammation with sclerosis and thickening of the wall of the paranasal sinuses. Half of cases reported intra-sinus metallic calcifications [16]. MRI shows fungal ball as isoor hypo-intense on T1 and marked hypo-intense on T2 [17]. More cases of sphenoid fungal ball have been diagnosed since the utilization of CT, MRI and nasal endoscopy in the diagnosis. Eighteen definitive diagnosis of fungal ball proved postoperatively by microbiological and histopathological examinations. The aim line of therapy is surgery by using endoscopic approaches (trans-nasal or transethmoidal) (Figure 6). The transnasal approach is preferred because it preserves the ethmoid sinus. The trans-ethmoidal approach is recommended in case of posterior ethmoid sinus disease accompanying the fungal ball [18].

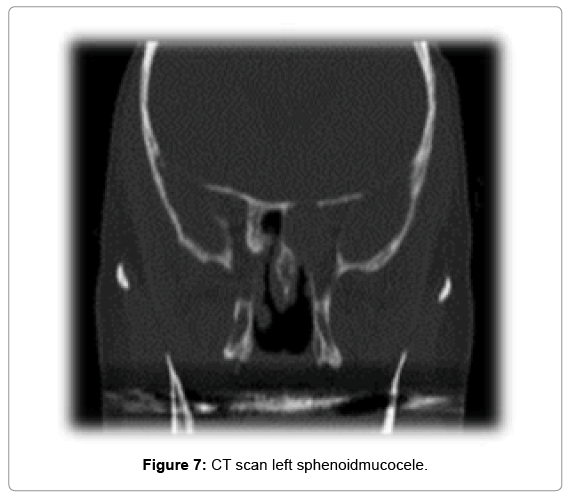

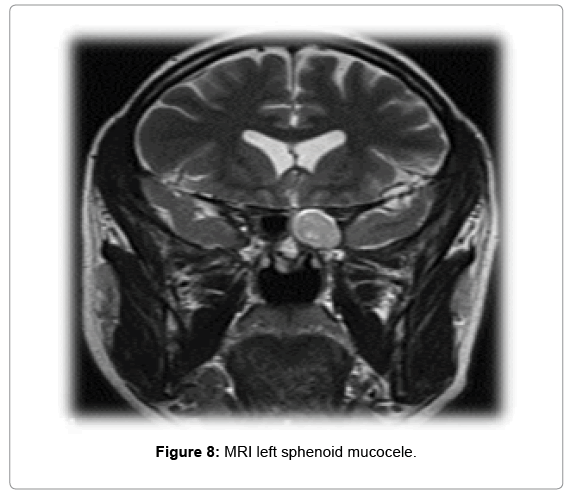

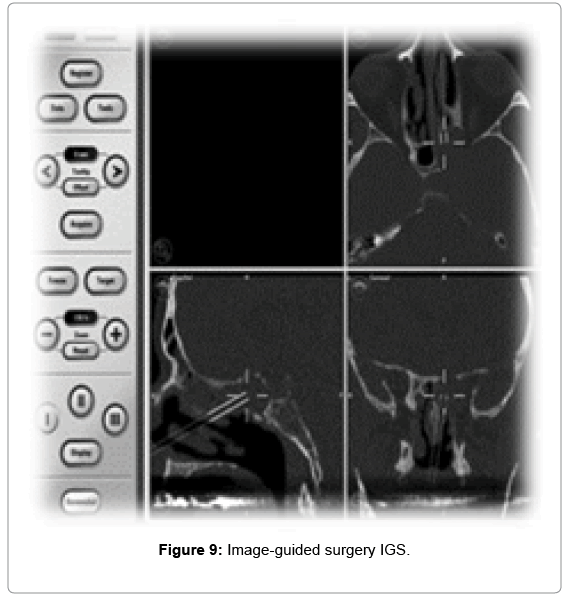

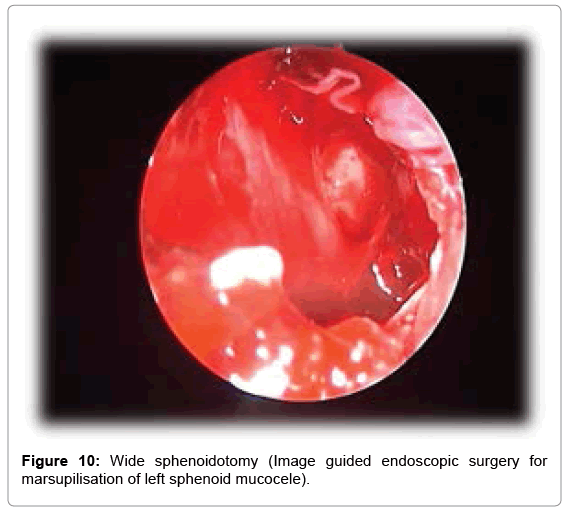

Mucocele: Only two cases of mucocele were identified in our series of cases. It has been reported that sphenoid sinus mucocele presents 1%- 2% of all para-nasal sinuses mucoceles [6]. Retention of mucoid secretion within the sinus which results in thinning, distension and erosion of the sinus bony walls is the pathophysiology of the disease. It is commonly present in the frontal sinus, followed by the anterior ethmoidal sinus. Sphenoid sinus mucocele can be presented with headache, visual disturbance due to optic or oculo-motor, trochlear and abducent nerves involvement, diplopia and external ophthalmoplegia [19]. CT scan is the main tool for diagnosis of sphenoid sinus mucocele. Figure 7 shows CT scane findings of one of our cases. MRI scan of one of our cases (Figure 8) shows a low signal on T1 and a high signal on T2. Regarding management, if asymptomatic mucocele, it can be leaved without any surgical intervention. Surgical intervention is recommended when it is symptomatic, or complicated. Surgical treatment of sphenoid mucocele is by endoscopic transnasal image-guided sphenoidotomy as illustrated in Figure 9. The aim of surgery is to perform wide sphenoidotomy to allow adequate drainage and to avoid recurrences of the disease (Figure 10). Another line of management is Marsupialization of the mucocele as it showed acceptable results.

Conclusion

Isolated sphenoid inflammatory disease is rare. Because of the relation of the sphenoid sinus to important vital structures of the skull base, early diagnosis and treatment is important and can avoid serious intracranial and orbital complications. Histopathology and microbiology are important tools for definite diagnosis. The endo-nasal endoscopic wide sphenoidotomy is the treatment of choice for isolated sphenoid inflammatory diseases.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawson W, Reino AJ (1997) Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: An analysis of 132 cases. Laryngoscope 107: 1590-1595.

- Nour YA, Al-Madani A, El-Daly A, Gaafar A (2008) Isolated sphenoid sinus pathology: Spectrum of diagnostic and treatment modalities. Auris Nasus Larynx 35: 500-508.

- Sethi DS (1999) Isolated sphenoid lesions: Diagnosis and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 120: 730-736.

- Rice DH, Schaefer SD (2004) Anatomy of the Paranasal Sinuses. In: Rice DH, Schaefer SD (Eds.) Endoscopic Paranasal Sinus Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Van Cauwenberge P, Sys L, De Belder T, Watelet JB (2004) Anatomy and physiology of the nose and the paranasal sinuses. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 24: 1-17.

- Friedman A, Batra PS, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Lanza DC (2005) Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: Etiology and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133: 544-550.

- Sethi DS (1999) Isolated sphenoid lesions: Diagnosis and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 120: 730-736.

- Lew D, Southwick FS, Montgomery WW, Weber AL, Baker AS (1983) Sphenoid sinusitis. A review of 30 cases. N Engl J Med 309: 1149-1154.

- Friedman A, Batra PS, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Lanza DC (2005) Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: Etiology and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133: 544-550.

- Sethi DS (1999) Isolated sphenoid lesions: Diagnosis and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 120: 730-736.

- Socher JA, Cassano M, Filheiro CA, Cassano P, Felippu A (2008) Diagnosis and treatment of isolated sphenoid sinus disease: A review of 109 cases. Acta Otolaryngol 128: 1004-1010.

- Brook I (2002) Bacteriology of acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 111: 1002-1004.

- Ruoppi P, Seppä J, Pukkila M, Nuutinen J (2000) Isolated sphenoid sinus diseases: Report of 39 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126: 777-781.

- Bent JP, Kuhn FA (1994) Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 111: 580-588.

- Illing EA, Dunlap Q, Woodworth BA (2015) Outcomes of pressure-induced cranial neuropathies from allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 152:541–545.

- Bent JP, Kuhn FA (1994) Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 111: 580-588.

- Aribandi M, McCoy VA, Bazan C (2007) Imaging features of invasive and noninvasive fungal sinusitis: A review. Radiographics 27: 1283-1296.

- Pagella F, Pusateri A, Matti E, Giourgos G, Cavanna C, et al. (2011) Sphenoid sinus fungus ball: Our experience. Am J Rhinol Allergy 25: 276-280.

- Soon SR, Lim CM, Singh H, Sethi DS (2010) Sphenoid sinus mucocele: 10 cases and literature review. J Laryngol Otol 124: 44-47.

Citation: Alali MS, Al Khatib A, AlAzzeh G, Al Momen A (2018) Isolated Sphenoid Inflammatory Diseases. Otolaryngol (Sunnyvale) 8: 357. DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000357

Copyright: © 2018 Alali MS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 6119

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Nov 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 5224

- PDF downloads: 895