Case Report Open Access

Intramural Hematoma of the Small Intestine in a Patient with Severe Hemophilia A. Case Report and Review of the Literature

H.M. Marcos Prieto1*, C. Pinero Perez1, J.M. Bastida Bermejo2, D. Perez Corte1, C. Revilla Morato1, A. Jimenez Jurado1, V. Calabuig Mazzola1, J.M.Gonzalez Santiago1, Y. Jamanca Poma1, A. Mora Soler1, J.R. González Porras2 and A.Rodriguez Pérez1

1Department of Digestive System Health Care Complex of Salamanca, Salamanca Institute for Biomedical Research (IBSAL), Spain

2Department of Hematology Health Care Complex of Salamanca. Salamanca Institute for Biomedical Research (IBSAL), Spain

- *Corresponding Author:

- H.M. Marcos Prieto

Health Care Complex of Salamanca.

Salamanca Institute for Biomedical Research (IBSAL)

Digestive System, san vicente nº182, Espana, salamanca

salamanca 37007, Spain

Tel: +34665085106

E-mail: h.mp@hotmail.es

Received date: Nov 21, 2015 Accepted date: Dec 14, 2015 Published date: Dec 21, 2015

Citation: Prieto HMM, Perez CP, Bermejo JMB, Corte DP, Morato CR, et al. (2015) Intramural Hematoma of the Small Intestine in a Patient with Severe Hemophilia A. Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Gastrointest Dig Syst 5:363. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000363

Copyright:© 2015 Prieto HMM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

Intestinal subocclusion is a clinical picture characterized by an incomplete interruption of the distal progression of the intestinal contents, and it may be due to multiple causes. We present here the case of a 20-year-old male with severe hemophilia A who developed symptoms of periumbilical abdominal pain and intestinal subocclusion. The CT scan revealed submucosal hemorrhage in the jejunum and dilatation of the proximal segments. A conservative treatment with plasmatic factor VIII was applied and the patient showed good response to the treatment and resolution of the intramural hematoma. With this case we want to highlight this intestinal manifestation of hemophilia, its atypical clinical behavior as intestinal subocclusion and its good response to a conservative treatment with factor VIII, as opposed to surgery as the first therapeutic option. We also offer a review of the last cases of hematomas in the gastrointestinal tract in hemophiliac patients.

Keywords

Hemophilia A; Intramural hematoma; Small intestine

Introduction

Intestinal subocclusion is a clinical picture caused by an incomplete interruption of the distal progression of the intestinal contents, and it may be due to multiple causes, mainly extrinsic, such as hernias, volvuli, adherences and masses (abscesses, hematomas and tumors), and also intrinsic, such as inflammatory stenosis, polyps, foreign bodies and neoplasms, among others.

On the other hand, gastrointestinal hemorrhages are currently relatively common, and one of their main causes is the widespread use of oral anticoagulants or their accidental overdose [1]. They are considered a common complication in cases of hemophilia, with an incidence between 10% and 25% [1]. However, submucosal hematomas on the abdominal wall are less frequent [1], both in anticoagulated patients and in hemophiliacs. Spontaneous intramural hemorrhage is a rare finding characterized by abdominal pain, and depending on its severity and location, it may imitate the symptoms of digestive tract obstruction. We describe an atypical presentation of an episode of intestinal obstruction in a 20-year-old male patient diagnosed with severe hemophilia A. We review the cases published in the literature with intramucosal hemorrhages in the gastrointestinal tract, as well as their diagnostic and therapeutic management.

Case Report

We present the case of a 20-year-old male patient diagnosed with severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C<1%) from birth in his country of origin and who had never received specific treatment until he arrived in Spain at age 19. The patient was assessed by the Department of Hematology of our hospital and secondary prophylaxis with plasma factor VIII with high concentration of von Willebrand factor (40UI/kg) was administered three times a week (Malmo protocol) [2]. He also required rehabilitating treatment due to a severe arthropathy on elbows, knees and ankles. Once that the prophylactic treatment was started, the doses had to be intensified in two occasions due to repeated hemarthrosis on the elbow and knee, respectively.

At age 22, the patient was admitted as an emergency with generalized abdominal pain of 5 days of evolution. The pain was constant, mainly located on the periumbilical region. It did not change with food intake or changes in posture. The patient did not report any traumatic background. 24 hours before the pain had increased its intensity and there were nauseas, vomiting and slight fever. He did not present with diarrhea.

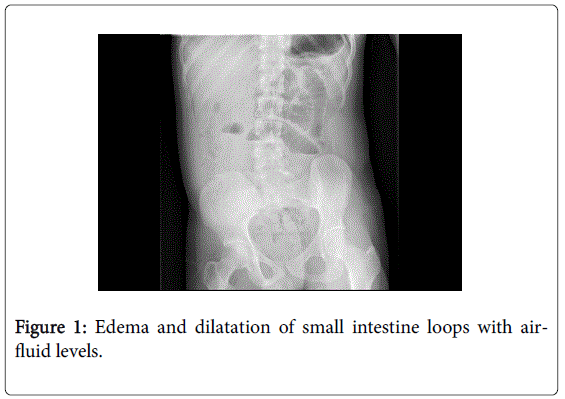

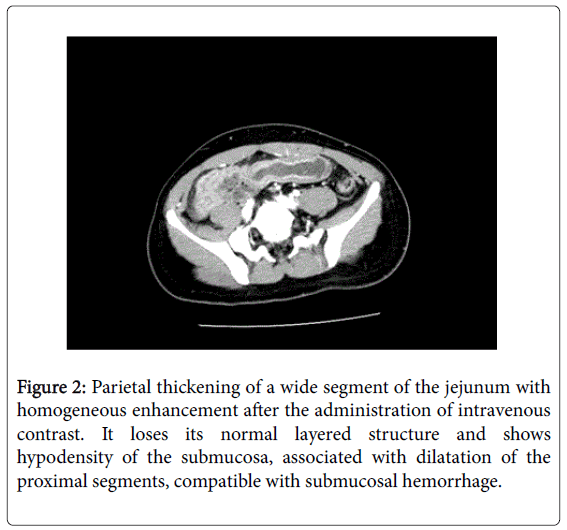

The physical examination revealed abdominal pain on palpation, mainly on the periumbilical area, with a slightly distended and tympanic abdomen, with normal air-fluid sounds. The analysis did not show any noticeable alteration, with normal coagulation tests (prothrombin activity: 18%; prothrombin time: 1.02 INR; activated partial prothrombin time: 40.0 seconds), hemoglobin: 15.9 d/dL; 273000 platelets/μL and 9810 leukocytes/μL without neutrophilia. The abdominal X-ray in standing position (Figure 1) showed edema and dilatation of the loops of the small intestine with air-fluid levels. Given the suspicion of intestinal obstruction, a computerized tomography scan was performed (CT), and it revealed a parietal thickening in a wide segment of the jejunum, with homogeneous enhancement after the administration of intravenous contrast. The scan also showed the loss of a normal layered structure and hypodensity of the submucosal layer associated to a dilatation of the proximal segments which is compatible with submucosal hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Parietal thickening of a wide segment of the jejunum with homogeneous enhancement after the administration of intravenous contrast. It loses its normal layered structure and shows hypodensity of the submucosa, associated with dilatation of the proximal segments, compatible with submucosal hemorrhage.

The patient was hospitalized with digestive rest and nasogastric decompression. Also, plasma factor VIII with high concentration of von Willebrand factor was administered intravenously every 12 hours for seven days, with monitoring of FVIII:C>80% and a gradual descent of the need to administer FVIII. In addition, no anemization was observed and the patient did not require support with a transfusion or iron. The pain disappeared progressively and afterwards the patient started oral diet with good tolerance. The control CT scan performed 7 days after admission shows that the hematoma had resolved completely and the patient was discharged with no recurrences so far.

Discussion

It is known that the most common cause of intramural spontaneous hematoma in the small intestine is the intake of oral anticoagulants [1]. Gastrointestinal bleeding in hemophiliac patients may appear in between 10% and 25% of the cases, and up to 85% of them are due to peptic ulcers [3]. These figures have been growing over the last years due to the introduction of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of chronic hemophilic arthropathy [4]. Bleeding on the intestinal wall is rare [5]. According to the literature, and extending the review carried out by Katsumi et al. in 2006 [6], there are 33 described cases of intramural hematoma of the gastrointestinal tract from 1964 to this day. The age ranged from 7 to 78 years. In this group, 15 patients showed an hematoma on the small intestine [5-7,10-16], 5 on the stomach [17-21], 4 on the esophagus [22-25], 4 on the duodenum [26], and 2 on the colon [8,16]. Three cases of transient intestinal invaginations were observed [14,27,28] two of which were resolved without surgery [14,27]. The most common physiology might be the rupture of the terminal arteries as they enter the muscle layer of the intestinal wall. The hemorrhage dissects the wall between the muscularis mucosae and the muscle layers, but the viability of the mucosa is preserved [29,30]. Computerized tomography is the diagnostic method of choice because it is highly sensitive and it defines the location and extension of the hemorrhage [1,32]. An essential factor in this type of hemorrhage is the identification of their cause. In the event of the absence of trauma, spontaneous gastrointestinal hemorrhages may be associated both to an infection with Helicobacter pylori [33] and to the use of NSAIDs [34], and they may even be due to the development of an inhibitor, as is the case in up to 30% of all cases of severe hemophilia A [35]. The non-surgical medical treatment should be the initial approach [1,6,31], whereas surgery should be reserved for cases in which a complication is suspected, such as intestinal ischemia, perforation, peritonitis, intra-abdominal hemorrhage and untreatable obstruction [1,31]. General measures include intestinal rest, nasogastric decompression, and correction of the electrolytic alterations. It is essential to start treatment on the shortage of factor VIII, to increase its levels >80% in the acute stage and to continue with maintenance treatment afterwards in order to keep FVIII around 50% for 14 days [36,37]. In the cases in which the cause is the development of an inhibitor, it is necessary to identify it by verifying its titer with the Bethesda technique [38], because an early detection makes it possible to choose an adequate treatment based on immune tolerance [39]. In case of failure to immune tolerance or bleeding which cannot be controlled after reestablishing factor VIII, activated prothrombin complex concentrate (APCC) may be administered, as well as recombinant factor VIIa (rVIIa) [5-7] and even anti-CD20 [40]. In our case, the cause of the hematoma was an abdominal trauma, and the patient showed good evolution with the treatment that was applied.

Conclusion

This case tries to underline the possibility that hemophiliac patients have of suffering from submucosal hematomas of the gastrointestinal tract with or without prior trauma, apart from the most common problems, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, hemarthrosis, intracranial hematomas or hematuria. In some cases, intramural hematoma may lead to an atypical behavior with intestinal obstruction symptoms, as in the case we present here. We wish to highlight the importance and sensitivity for diagnosis of computerized tomography in cases of clinical suspicion, and to emphasize the good response to an early conservative medical treatment in the cases described, compared with an initial surgical approach, which should be implemented only in complicated cases (Table 1).

| Age | Coagulation disorder (activity of Factor VIII) | Inhibitor titer (BU/mL) | Location in the gastrointestinal tract | Treatment | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | Hemophilia A | - | Jejunum | FVIII | This report |

| 2 | 7 | Severe hemophilia A | >10 | sigma | APCC, rVIIa | [8] |

| 3 | 37 | Hemophilia A | - | Distal ileum | FVIII | [7] |

| 4 | 17 | Severe hemophilia A (<1%) | 1048 | Jejunum | APCC, rVIIa | [6] |

| 5 | 34 | Severe hemophilia A | High | Jejunum | rVIIa | [5] |

| 6 | 74 | Mild hemophilia A | 27 | Small intestine | APCC, rVIIa | [10] |

| 7 | 78 | Acquired FVIII inhibitor | >15 | Esophagus | Intravenous human immunoglobulin, oral prednisolone, andoral cyclophosphamide | [22] |

| 8 | n.s | Hemophilia A | - | Esophagus | FVIII | [23] |

| 9 | 14 | Severe hemophilia A (<1%) | - | Jejunum | FVIII | [11] |

| 10 | 47 | Severe hemophilia A | 0.9 | Small intestine | FVIII | [12] |

| 11 | 31 | Hemophilia A (4.5%) | - | Esophagus | Cryoprecipitate and antituberculous treatment | [24] |

| 12 | Child | Hemophilia | - | Duodenum | Deferred surgery | [26] |

| 13 | Child | Hemophilia | - | Duodenum | Deferred surgery | [26] |

| 14 | Child | Hemophilia | - | Duodenum | Conservative therapy | [26] |

| 15 | Child | Hemophilia | - | Duodenum | Conservative therapy | [26] |

| 16 | 31 | Hemophilia A | - | Small intestine | Laparotomy | [13] |

| 17 | 40 | Hemophilia A | - | Jejunum | FVIII | [13] |

| 18 | 8 | Hemophilia A | - | Proximal jejunum, jejuno-jejunal intussusception |

FVIII, laparotomy | [28] |

| 19 | 9 | Severe hemophilia A | 4~8 | Stomach | FVIII | [17] |

| 20 | 34 | Hemophilia A | Positive | Small intestine | FVIII | [14] |

| 21 | 19 | Hemophilia A | - | Small intestine | FVIII | [14] |

| 22 | 47 | Hemophilia A | - | Jejunum | FVIII | [14] |

| 23 | 16 | Hemophilia B | - | Ileocolic intussuception | FIX | [14] |

| 24 | 23 | Severe hemophilia A (<1%) | - | Stomach | Cryoprecipitate | [19] |

| 25 | 13 | Severe hemophilia A (<1%) | - | Ileocolic intussuception | Cryoprecipitate, barium enema reduction | [27] |

| 26 | 38 | Hemophilia A | - | Esophagus | FVIII | [23] |

| 27 | 22 | Hemophilia A | - | Stomach | Cryoprecipitate | [18] |

| 28 | 16 | Hemophilia A | - | Small intestine | Fresh blood | [15] |

| 29 | 8 | Hemophilia A | - | Stomach | Anti-hemophilic globulin | [20] |

| 30 | 15 | Hemophilia A | - | Ileum | Anti-hemophilic globulin | [16] |

| 31 | 21 | Hemophilia A | - | Jejunum | Anti-hemophilic globulin | [16] |

| 32 | 10 | Hemophilia A | - | Colon | Anti-hemophilic globulin | [16] |

| 33 | 8 | Hemophilia A | - | Stomach | Fresh frozen plasma | [21] |

Table 1: Cases of Intramural Hematoma of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Patients with Hemophilia*. (Adapted and modified from Katsumi et al. [6]). *All patients are male. APCC indicates activated prothrombin complex concentrate; rVIIa, recombinant activated factor VII; FVIII, factor VIII; FIX, factor IX.

References

- Sorbello MP, Utiyama EM, Parreira JG, Birolini D, Rasslan S (2007) Spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma induced by anticoagulant therapy: review and case report. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 62: 785-790.

- Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Zettervall O (1988) Induction of immune tolerance in patients with hemophilia and antibodies to factor VIII by combined treatment with intravenous IgG, cyclophosphamide, and factor VIII. N Engl J Med 318: 947-950.

- Mittal R, Spero JA, Lewis JH, Taylor F, Ragni MV, et al. (1985) Patterns of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in hemophilia. Gastroenterology 88: 515-522.

- Cagnoni PJ, Aledort L (1994) Gastrointestinal bleeding in hemophilia as a complication of the use of over the counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Hematol 47: 336-337.

- Ramadan KM, Lowry JP, Wilkinson A, McNulty O, McMullin MF, et al. (2005) Acute intestinal obstruction due to intramural haemorrhage in small intestine in a patient with severe haemophilia A and inhibitor. Eur J Haematol 75: 164-166.

- Katsumi A, Matsushita T, Hirashima K, Iwasaki T, Adachi T, et al. (2006) Recurrent intramural hematoma of the small intestine in a severe hemophilia A patient with a high titer of factor VIII inhibitor: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol 84: 166-169.

- Carkman S, Ozben V, Saribeyoğlu K, Somuncu E, Ergüney S, et al. (2010) Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the small intestine. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 16: 165-169.

- Yank IV, Spasova MI, Andonov VN (2014) Endoscopic diagnosis of intramural hematoma in the colon sigmoideum in a child with high titer inhibitory hemophilia A Folia Medica 56: 126-128

- Khilnani MT, Marshak rh, eliasoph j, wolf bs (1964) intramural intestinal hemorrhage. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 92: 1061-1071.

- Santoro R, Iannaccaro P (2004) Spontaneous intramural intestinal haemorrhage in a haemophiliac patient. Br J Haematol 125: 419.

- Ettingshausen CE, Saguer IM, Kreuz W (1999) Portal vein thrombosis in a patient with severe haemophilia A and F V G1691A mutation during continuous infusion of F VIII after intramural jejunal bleeding—successful thrombolysis under heparin therapy. Eur J Pediatr 158: S180-182.

- Gamba G, Maffé GC, Mosconi E, Tibaldi A, Di Domenico G, et al. (1995) Ultrasonographic images of spontaneous intramural hematomas of the intestinal wall in two patients with congenital bleeding tendency. Haematologica 80: 388-389.

- Tsuchie K, Suzuki M, Yamada M, Hoshino S, Chin H (1985) [Intramural hematoma of the small intestine due to hemophilia A: report of two cases]. Rinsho Hoshasen 30: 1599-1602.

- Eiland M, Han SY, Hicks GM Jr (1978) Intramural hemorrhage of the small intestine. JAMA 239: 139-142.

- Sharma ID, Chandra D, Charan A, Sinha KN (1972) Haemophilia presenting as acute mechanical small intestinal obstruction. J Indian Med Assoc 59: 109-110.

- Dodds WJ, Spitzer RM, Friedland GW (1970) Gastrointestinal roentgenographic manifestations of hemophilia. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 110: 413-416.

- Gordon RA, d'Avignon MB, Storch AE, Eyster ME (1981) Intramural gastric hematoma in a hemophiliac with an inhibitor. Pediatrics 67: 417-419.

- Felson B (1974) Intramural gastric lesion with sudden abdominal pain. JAMA 230: 603-604.

- Yoshimura H, Ohishi H, Inoue K, Ozaki M, Yoshimura Y, et al. (1978) [Roentgenographic manifestations of intramural hematoma of the stomach in a hemophiliac male (author's transl)]. Rinsho Hoshasen 23: 1405-1408.

- Wright FW, Matthews JM (1971) Hemophilic pseudotumor of the stomach. Radiology 98: 547-549.

- Grossman H, Berdon WE, Baker DH (1965) reversible gastrointestinal signs of hemorrhage and edema in the pediatric age group. Radiology 84: 33-39.

- Horan P, Drake M, Patterson RN, Cuthbert RJ, Carey D, et al. (2003) Acute onset dysphagia associated with an intramural oesophageal haematoma in acquired haemophilia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 15:205-207.

- Chawla A, Blume MH, Insel J (2002) Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Ann Intern Med 137: 73-74.

- Intragumtornchai T, Israsena S, Benjacholamard V, Lerdlum S, Benjavongkulchai S (1992) Esophageal tuberculosis presenting as intramural esophagogastric hematoma in a hemophiliac patient. J Clin Gastroenterol 14: 152-156.

- Oldenburger D, Gundlach WJ (1977) Intramural esophageal hematoma in a hemophiliac. An unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. JAMA 237: 800.

- Jewett TC Jr, Caldarola V, Karp MP, Allen JE, Cooney DR (1988) Intramural hematoma of the duodenum. Arch Surg 123: 54-58.

- Fripp RR, Karabus CD (1977) Intussusception in haemophilia: a case report. S Afr Med J 52: 617-618.

- LeBlanc KE (1982) Jejuno-jejunal intussusception in a hemophiliac: a case report. Ann Emerg Med 11: 149-151.

- Hale JE (1975) Intramural intestinal haemorrhage: a complication of anticoagulant therapy. Postgrad Med J 51: 107-110.

- Nakayama Y, Fukushima M, Sakai M, Hisano T, Nagata N, et al. (2006) Intramural hematoma of the cecum as the lead point of intussusception in an elderly patient with hemophilia A: report of a case. Surg Today 36: 563-565.

- Jarry J, Biscay D, Lepront D, Rullier A, Midy D (2008) Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the sigmoid colon causing acute intestinal obstruction in a haemophiliac: report of a case. Haemophilia 14:383-384.

- Girolami A, Vettore S (2012) Rare and Unusual bleeding manifestations in Congenital Bleeding Disorderes: An annotated Review. Clinical and applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis 18:121-127

- Schulman S, Rehnberg AS, Hein M, Hegedus O, Lindmarker P, et al. (2003) Helicobacter pylori causes gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with congenital bleeding disorders. Thromb Haemost 89: 741-746.

- Eyster ME, Asaad SM, Gold BD, Cohn SE, Goedert JJ; Second Multicenter Hemophilia Study Group (2007) Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in haemophiliacs: incidence and relation to use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Haemophilia 13: 279-286.

- Collins PW, Palmer BP, Chalmers EA, Hart DP, Liesner R5, et al. (2014) Factor VIII brand and the incidence of factor VIII inhibitors in previously untreated UK children with severe hemophilia A, 2000-2011. Blood 124: 3389-3397.

- Kouides PA, Fogarty PF (2010) How do we treat: upper gastrointestinal bleeding in adults with haemophilia. Haemophilia 16: 360-362.

- Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Key NS, Kitchen S, et al. (2013) Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia 19: e1-47.

- Verbruggen B, Novakova I, Wessels H, Boezeman J, van den Berg M, et al. (1995) The Nijmegen modification of the Bethesda assay for factor VIII:C inhibitors: improved specificity and reliability. Thromb Haemost 73: 247-251.

- Hay CR, DiMichele DM; International Immune Tolerance Study (2012) The principal results of the International Immune Tolerance Study: a randomized dose comparison. Blood 119: 1335-1344.

- Coppola A, Di Minno MN, Santagostino E (2010) Optimizing management of immune tolerance induction in patients with severe haemophilia A and inhibitors: towards evidence-based approaches. Br J Haematol 150: 515-528.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11756

- [From(publication date):

December-2015 - Jul 13, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10799

- PDF downloads : 957