Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment (IPPT) in the Management of Patients Motivated to Move from Problematic Alcohol Consumption (PAC) to Moderate Alcohol Consumption (MAC)

Received: 01-Aug-2023 / Manuscript No. jart-23-110590 / Editor assigned: 03-Aug-2023 / PreQC No. jart-23-110590 / Reviewed: 17-Aug-2023 / QC No. jart-23-110590 / Revised: 21-Aug-2023 / Manuscript No. jart-23-110590 / Accepted Date: 27-Aug-2023 / Published Date: 28-Aug-2023 DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000562 QI No. / jart-23-110590

Abstract

Alcohol is a product widely consumed in our liberal society in family and friendly gatherings, in national, international, traditional, cultural, and religious holidays... Although it is a symbol of bond in social relations, it is nonetheless true that alcohol can cause significant health, social relations, and security problems. The study aimed to help the patient control their problematic alcohol consumption using cognitive and behavioral therapy, psychopharmacotherapy, and statistical analysis to understand their addictive behaviors and perform cognitive and emotional restructuring. Data was collected based on the patient's self-observations for 406 days using a preestablished form, MAST and AUDIT questionnaires, and statistical analysis with SPSS to facilitate the analysis. The results of the study showed that regular monitoring and analysis of behavior and thoughts regarding alcohol can help a patient better understand and control their consumption. Combining cognitive and behavioral therapies with psych pharmacotherapy can also be effective in achieving the goal of total abstinence from hard drugs. Correlations between variables such as alcohol cravings, strategies for coping with cravings, and results were also highlighted, indicating that certain factors such as day, time, and location may be risk indicators for relapse. It is important to continue monitoring and analyzing this data to help patients better understand and control their alcohol consumption.

Keywords

Problematic alcohol consumption; Moderate alcohol consumption; Cognitive and behavioral therapies; Psych pharmacotherapy

Introduction

For over 10,000 years, humans have been consuming fermented beverages, including alcohol. Its positive and negative impact on health has been the subject of many debates. Alcohol affects the body in various ways, not only impacting the drinkers themselves but also their families, friends, and communities, often leading to violence and accidents [1]. It has been implicated in 40% of violent crimes [2], 15% of drownings [3], and is responsible for one in seven deaths on the road [4]. Yet, alcohol consumption seems to be on the rise. According to estimates from the World Health Report [5], at least 10 billion people worldwide regularly consume alcohol. In India, alcohol consumption is so deeply rooted in the culture that it is no longer recognized as a drug or even a problem [6]. However, with increasing globalization, acceptance and consumption of alcohol have grown, leading to serious ramifications. It is therefore crucial to reduce alcohol demand, whether legal or illegal, as it can have significant health, family, and societal consequences. Similar to India's Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act of 1985 (NDPS) [7], which provides the current framework for controlling drug abuse and trafficking in the country, similar provisions are needed, as in Canada, where the law stipulates that only the federal government has the right to import and distribute alcohol to provinces and territories, while it is the responsibility of provinces and territories to regulate the sale and consumption of alcohol within their respective jurisdictions. There are challenges in regulating alcohol consumption due to the difficulty in finding a balance between allowing adults to consume alcohol responsibly and protecting high-risk individuals. Clinicians do not always agree on the harmful effects of alcohol and rates of addiction, so it is important to continue research to better understand these subjects and help identify high-risk individuals [8]. It was during the 18th century that addiction specialists began to consider addictions not as a lack of willpower or absence of religious morality but as a disease requiring care. Prejudices began to slowly change in professional circles, but they remain ingrained in popular thinking [9]. According to experts, substance use is neither a lack of willpower nor a vice but a brain disease that goes beyond behavioral issues. This perspective is also recognized by the World Health Organization [10]. It is common for some patients with a history of treatment for substance use disorder (SUD) to continue struggling with alcohol addiction, alternating between periods of relapse and abstinence [11]. These relapses can be associated with psychiatric comorbidities such as mood disorders and anxiety disorders [12]. These patients may have more realistic requests from mental health professionals, asking for help in controlling their alcohol consumption rather than seeking complete abstinence due to societal and cultural pressures [13f], their social or professional environment, or their own weakness in the face of addiction [14]. In addition to individual social and psychological factors related to each patient seeking care, some patients also refer to studies that have shown the potential benefits of controlled or moderate alcohol consumption from a medical [15] and psychological perspective [16]. However, therapists in most public or private institutions may not have appropriate treatment plans to meet the demands of these patients based on their personal and familial medical histories related to alcohol and other psychoactive substance consumption [17]. It is important to consider the patient's social, economic, and even physical biological environment to provide tailored care to this growing population [18]. Some therapeutic approaches propose the use of Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment (IPPT) combined with psychopharmacology and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to help patients better manage their alcohol consumption [19]. By establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, this approach can help prevent excessive drinking and frequent psychiatric hospitalizations [20]. IPPT, combined with CBT, with or without psychopharmacotherapy [21], enables patients to control their alcohol consumption and prevent relapses into problematic alcohol consumption [22] and other hard drugs, addressing accumulated frustrations or the lack of appropriate treatment options focused on Controlled Alcohol Use (CAU).

Regularly conducted statistics by Addiction Suisse gather quantitative data on psychotropic substance consumption. It highlights practices related to certain drugs that are concentrated on weekends, such as ecstasy and cocaine. National statistics aim to determine the percentage of the population over 15 years old related to the type of consumption. The indicators considered are the number of times the substance has been used in one's lifetime, in the past year, in the past months, and daily. The authors hypothesize that individuals in the group who sporadically consume substances could be considered as having spontaneous control over their consumption, unlike those who consume daily. 3.1% of the population reported cannabis use in the past month, 0.1% for cocaine, and less than 0.1% for amphetamines. Alcohol is the most consumed substance, with 85.9% of the Swiss population aged 15 and over consuming it. If we subtract the 4.3% with chronic risky consumption, it can be objectively considered that 81.6% of the Swiss population consumes alcohol in a non-problematic pattern according to the Swiss Confederation [23]. The goal of treatment is not to push the patient to stop consuming alcohol at any cost until complete abstinence, but to have controlled, moderate, or balanced consumption in relation to their biopsychosocial status. Moderate consumption is reached when the health benefits of alcohol clearly outweigh the risks. The most recent consensus sets this point at a maximum of 1 or 2 drinks per day for men and a maximum of 1 drink per day for women. This is the definition used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025, and it is widely used in the United States. Moderate consumption is highly beneficial for health, as it can reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases, violence, accidents, etc., by 25 to 40%. On the other hand, consumption beyond this balance leads to domestic violence and road accidents [24]. However, increasing alcohol consumption to more than 4 drinks per day can increase the risk of hypertension, abnormal heart rhythm, stroke, heart attack, and death [25, 26-28]. In this context, we will present a clinical case that we followed in our outpatient department for 2 years to assist the transition from problematic alcohol consumption (PAC) to controlled and moderate alcohol consumption (CMC). To achieve this goal, the integrated psychiatric and psychotherapeutic treatment (IPPT) is necessary, and in our presented case, it involves the combination of psychopharmacotherapy and CBT.

Case study

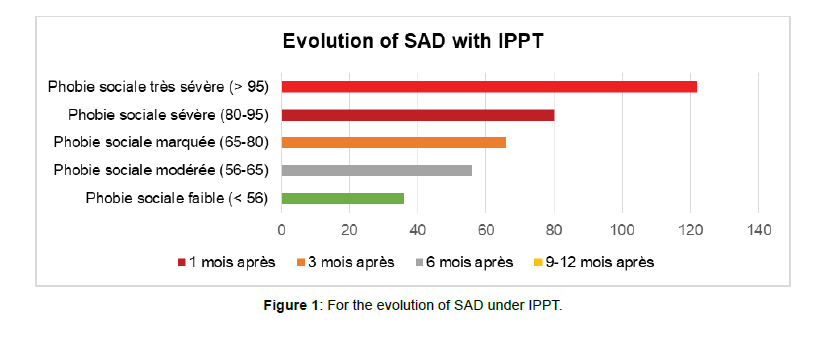

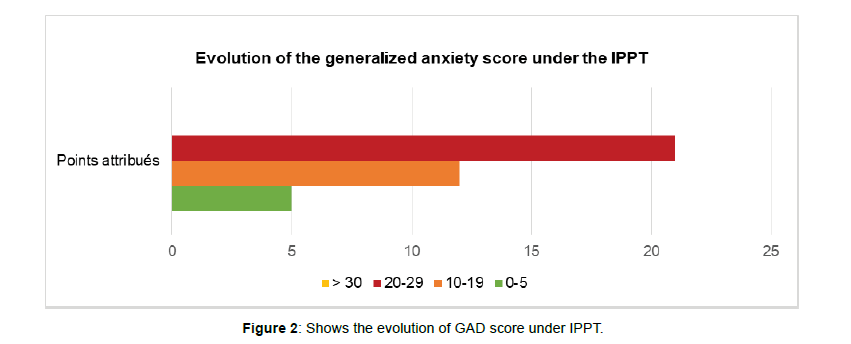

We have a 35-year-old young adult whom we will refer to as Martin for anonymity purposes. He began seeking treatment for problematic alcohol consumption at the age of 20 in addiction services in French-speaking Switzerland. Since that age, he has been dealing with problematic alcohol consumption (PAC) that gradually developed alongside a pathological shyness, which later received a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder (SAD). To socialize better and engage in weekend activities with his peers, he also developed problematic use of other substances (PUS), such as tobacco, followed by cannabis and heroin. From the age of 25, Martin has been under the care of outpatient addiction services mentioned earlier, and he has undergone several detoxification treatments in hospitals and clinics across French-speaking Switzerland. These mental health and addiction-related conditions have led to learning difficulties, long periods of unemployment, and job losses. During his Psychiatric initial assessment (PIA) in outpatient consultation at Psy-Scan Institute (PSI), Martin was receiving social assistance and living in social isolation far from his family in France. He is in a codependent relationship with his girlfriend who suffers even more than him from Figure 1 SAD and other issues related to PUS, except for heroin. Due to his desire to maintain this friendship and avoid being too alone, he committed to undergoing detoxification and substitution treatment for heroin with methadone until total abstinence. However, their codependences and emotional ties are reinforced by their PUS such as of tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol, which they both struggle to overcome since partially or completely being together. After receiving joint outpatient care at the addiction service in the canton of Neuchâtel, Martin's friend returns to join her family in a distant canton. Martin decides to seek help through a comprehensive treatment plan involving IPPT and specialized addiction follow-up, aiming to quit smoking motivated by financial constraints and the fear of developing lung cancer due to a family history of the condition. He also aims to reduce cannabis use motivated by a vocational reintegration program offered by the disability insurance office (DIO), along with motivational interviews as part of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). However, Martin struggles with his PUS, which serves as the only outlet and pleasure in his life and solitude, as it is the only way for him to socialize. He firmly believes that when alone, he experiences significant anxiety and depression, and when with others, he relies on PUS to cope with SAD, complicated by generalized anxiety disorder Figure 2 (GAD) and secondary depression. By seeking acceptance in social situations, he reinforces and maintains his dependence on alcohol. When Martin came to PSI, his request was not to become completely abstinent from alcohol but to achieve moderate alcohol consumption (MAC), controlled and manageable consumption, in other words, non-problematic alcohol use (NPAU), whether alone or in social situations.

Objectives

General objective

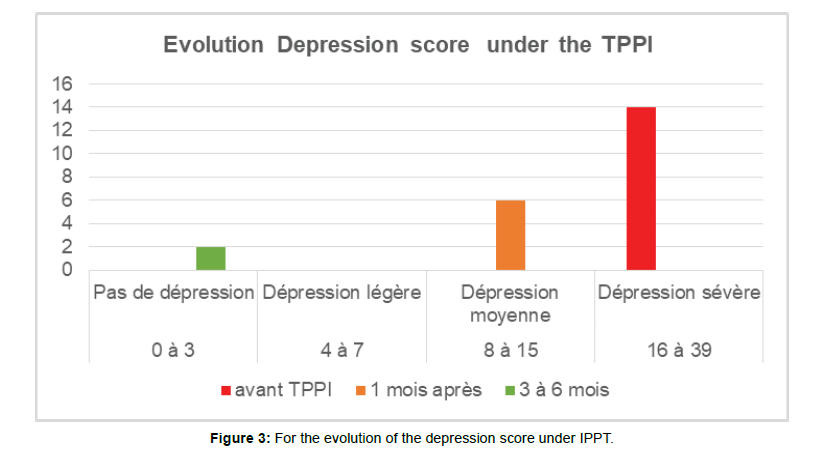

Assist the patient in maintaining total abstinence from other hard drugs through positive reinforcement, focusing energy not on complete abstinence from alcohol but on controlling alcohol consumption. Our approach involves providing the patient with tools derived from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and psychopharmacotherapy through Figure 3 IPPT without coercion, enabling them to better observe their behavior towards alcohol and generate better control over excessive consumption of this substance.

Specific objectives

a. Show the patient the link between their social anxiety and problematic alcohol use and establish an appropriate IPPT for social anxiety disorder (SAD).

b. Assist the patient in better observing their behavior towards alcohol consumption through a predefined self-observation grid. c. Have the patient report their self-observation grid during therapy sessions with their psychiatrist, ensuring compliance with the integrated psychiatric and psychotherapeutic treatment plan (IPPT), which combines CBT, pharmacotherapy, and Disulfiram.

d. Help the patient analyze their past behavior towards alcohol to better manage periods of abstinence or understand occasional and brief relapses through statistical analysis of the data.

e. Assist the patient in identifying high-risk behaviors and appropriate pharmacological, cognitive, and behavioral strategies to control or moderate alcohol consumption, based on correlations revealed through statistical analysis of the data.

f. Enable the patient to identify risk factors through correlations identified in the statistical analysis of the self-observation records, facilitating a better understanding and prevention of relapses and improved control over alcohol consumption.

g. Through statistical analysis of collected data, establish a functional analysis of the patient's response to alcohol consumption and identify the underlying pattern explaining their addictive behavior, facilitating necessary cognitive and emotional restructuring for better control over excessive alcohol consumption.

Method

Materials

Predefined self-observation grids provided to the patient at the end of each session, designed to collect patient-reported data stored in our psipap (Psy-Scan Institute psychiatric assessment) software.

• The self-observation grid consists of columns A, B, C, D, etc., where the patient notes and records observed behavioral, cognitive, relational, and spatiotemporal parameters and come with these data collected like homework at each session at PSI. These parameters are collected based on the patient's self-observations.

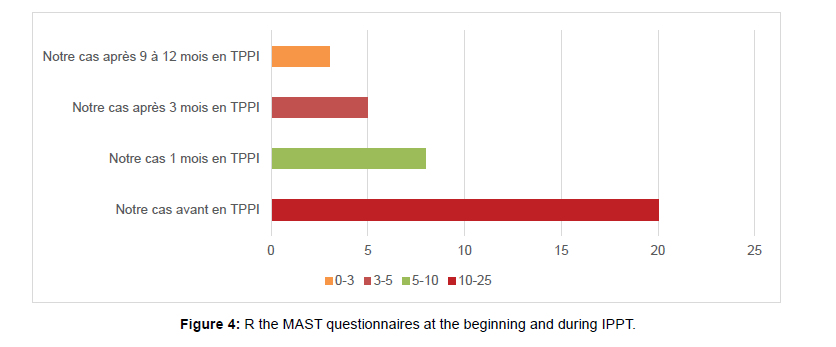

• The Selzer's MAST Figure 4 (Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test) questionnaire from 1971 is administered before the start of treatment, during treatment, and at the end of the IPPT. The results are stored in the psipap software, as mentioned earlier.

• The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) from 1987, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) are used to measure the intensity of anxio-depressive symptoms and especially social anxiety disorder (SAD) symptoms before and during IPPT. The results are also stored in the psipap software.

Study period

The patient was followed from February 1, 1998, to April 23, 1999, and all the data reported at each session were recorded in an Excel file as mentioned above and kept in the patient's medical record. In total, the patient collected data based on self-observations for 406 days, recording data on behaviors and thoughts related to alcohol craving.

Procedure

a. Data collection

The patient was instructed to fill in the predetermined columns with the date, day of the week, time of day, location (alone or accompanied), initial craving level (ICL) for alcohol, triggered automatic thoughts (TAT), and cognitive-behavioral strategies (CBS) used to avoid relapse. The ICL is rated from 0% to 100%, and after using CBS, the residual craving level (RCL) is also rated from 0% to 100%. The result is recorded as either failure (scored as -1 point) or success (scored as +1 point).

b. Statistical analysis using SPSS

To facilitate the analysis of the collected data, the variables were crossed and processed as follows:

• The time of day was grouped into four classes: ]11 am, 12 pm], ]12 pm, 6 pm], ]6 pm, 7 pm], ]7 pm, +].

• The patient is either at home alone (AHA), at home not alone (AHNA) or outside accompanied (OA) or outside not accompanied (ONA).

• The cognitive-behavioral strategies used (CBS) are grouped into four categories: water and/or various activities, alcohol consumption, inappropriate alcohol consumption (IAC), and sweets and/or various activities.

• The automatic thoughts triggered by cravings (ATC) are divided into two groups:

• After taking Disulfiram (ATD) and/or black thoughts on the one hand and

• Without taking Disulfiram (WTD) and/or black thoughts of the other

• The treatment of SAD was essentially provided here by pharmacological treatment based on Sertraline 50mg as a starting dose and after titration the effective dosage was observed at 200-300mg per day.

• The ICA and the SAD also benefited during the IPPT from CBT sessions focused on the exposure of my mental imagination (EMI), the management of stress and emotions (MSE) through relaxation and cognitive restructuring because of the errors of thought that are often associated with the self-image in the SAD. The CBT also helped a lot to stabilize the SAD and reduce the dose of Sertraline between 100mg to 200mg instead of 300mg per day.

• The post-treatment period in this study showed a stabilization of the MCA and its SAD with Sertraline from 50mg to 100mg in the period of social stress and fear of relapse with the practice of relaxation techniques learned during CBT.

• During the post-study period the patient remained with a MCA even without Disulfiram according to our observation thanks to the stabilization of his SAD.

Results

Results of the evolution of SAD symptoms and other anxiodepressive symptoms under

IPPT with Pharmacotherapy and CBT:

Results of the evolution of anti-depressive symptoms under IPPT

Result and Interpretation of the HAS-14 (Hamilton Anxiety Scale)

Result and Interpretation of the BDI-13 (Beck Depression Inventory)

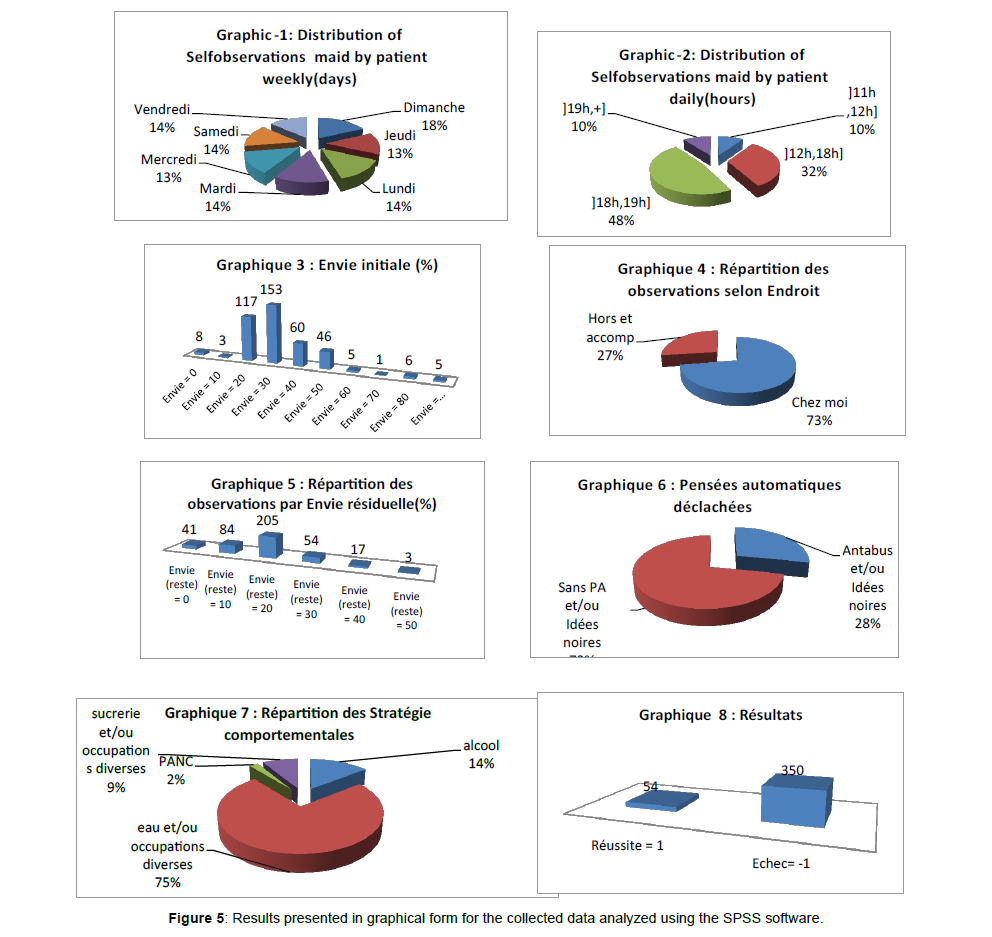

When analyzing the above graphs, the following findings can be observed for the recorded data over the 404 days

• Sundays accounted for 18% of the days where the patient reported inappropriate alcohol consumption (ICA), the highest percentage among the seven days of the week.

• More than 58% of ICA occurrences occurred after 6 PM.

• Most cravings were measured at 30% (154 times out of 404), while cravings exceeding 50% accounted for only 4.2% (17 times out of 404).

• The patient was alone at home during 73% of the ICA episodes.

• Among the four behavioral strategies used (BSU), the patient relied on water and/or various activities in 75% of cases (Figure 5).

• The most frequent residual craving (RC) after BSU or the final craving was at 20% (205 times out of 404). RC exceeding 20% accounted for 18.3% (74 times out of 404), and there were no RC instances exceeding 50% within a period of approximately 1 to 2 months.

• The overall failure rate, indicated by ICA, accounted for 86.6% (350 out of 404) until January 1, 2019.

a. Chronological results of cravings

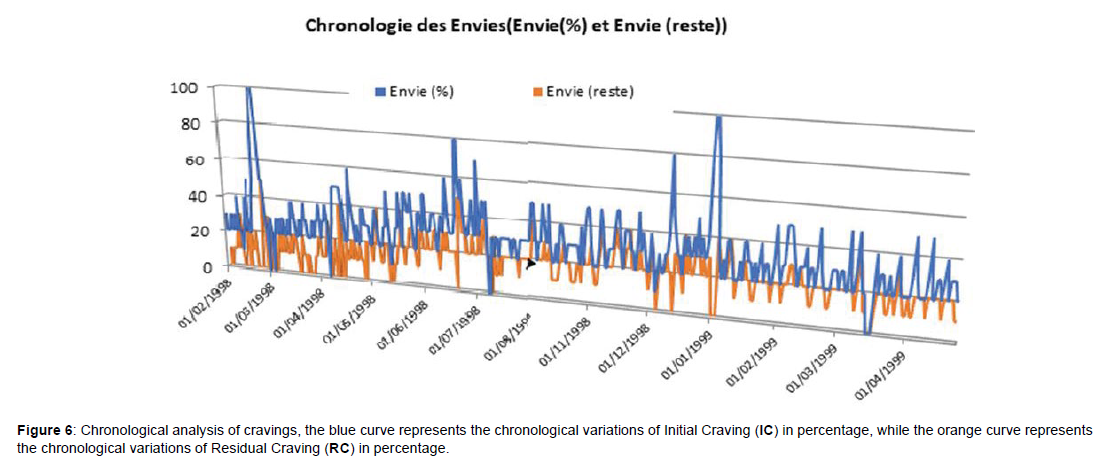

Graph 9: Chronology of cravings: Initial Craving (IC) and Residual Craving (RC) in (%):

These two curves of EI and ER are established after January 1, 1999 and confirm that lower amplitude of EI corresponds to a more stable and smaller amplitude of ER, which indicates effective control of alcohol consumption (CCA) by the patient (Figure 6).

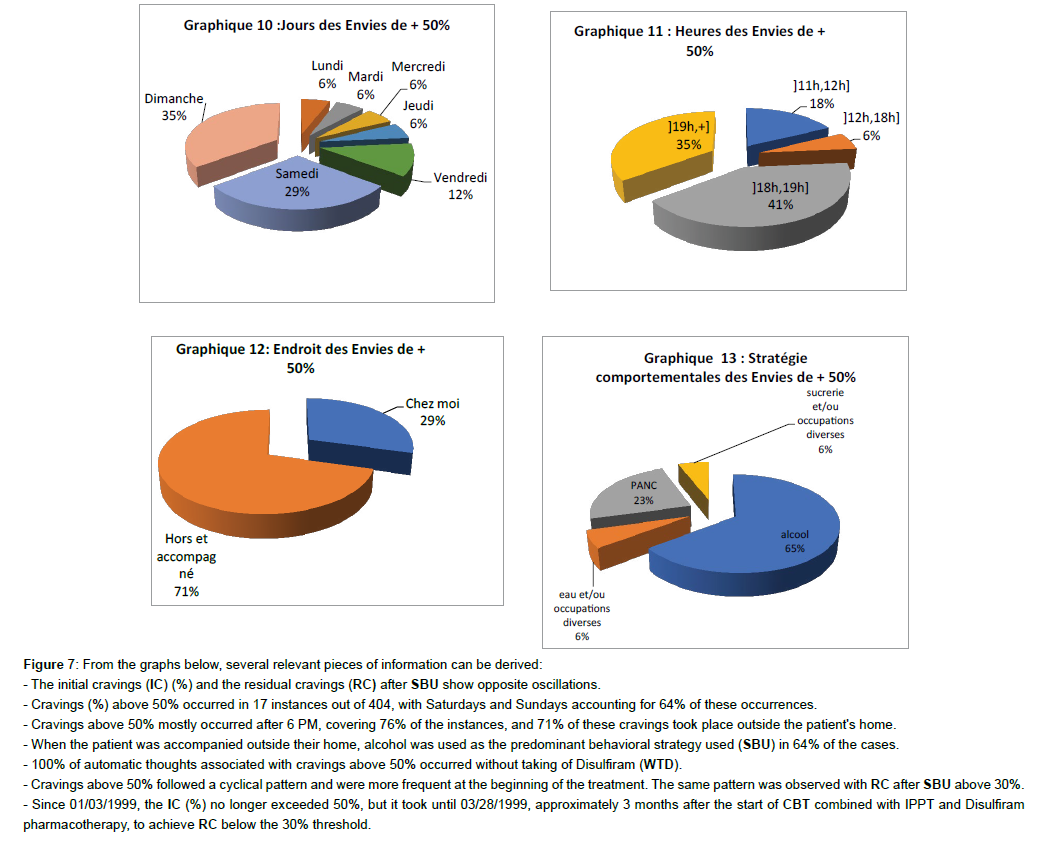

From the graphs below, several relevant pieces of information can be derived:

• The initial cravings (IC) (%) and the residual cravings (RC) after SBU show opposite oscillations.

• Cravings (%) above 50% occurred in 17 instances out of 404, with Saturdays and Sundays accounting for 64% of these occurrences (Figure 7).

- The initial cravings (IC) (%) and the residual cravings (RC) after SBU show opposite oscillations.

- Cravings (%) above 50% occurred in 17 instances out of 404, with Saturdays and Sundays accounting for 64% of these occurrences.

- Cravings above 50% mostly occurred after 6 PM, covering 76% of the instances, and 71% of these cravings took place outside the patient's home.

- When the patient was accompanied outside their home, alcohol was used as the predominant behavioral strategy used (SBU) in 64% of the cases.

- 100% of automatic thoughts associated with cravings above 50% occurred without taking of Disulfiram (WTD).

- Cravings above 50% followed a cyclical pattern and were more frequent at the beginning of the treatment. The same pattern was observed with RC after SBU above 30%.

- Since 01/03/1999, the IC (%) no longer exceeded 50%, but it took until 03/28/1999, approximately 3 months after the start of CBT combined with IPPT and Disulfiram pharmacotherapy, to achieve RC below the 30% threshold.

• Cravings above 50% mostly occurred after 6 PM, covering 76% of the instances, and 71% of these cravings took place outside the patient's home.

• When the patient was accompanied outside their home, alcohol was used as the predominant behavioral strategy used (SBU) in 64% of the cases.

• 100% of automatic thoughts associated with cravings above 50% occurred without taking of Disulfiram (WTD).

• Cravings above 50% followed a cyclical pattern and were more frequent at the beginning of the treatment. The same pattern was observed with RC after SBU above 30%.

• Since 01/03/1999, the IC (%) no longer exceeded 50%, but it took until 03/28/1999, approximately 3 months after the start of CBT combined with IPPT and Disulfiram pharmacotherapy, to achieve RC below the 30% threshold.

Discussion

Discussion of the results

• The correlation Table 1 between the numerical variables (IC (%), RC (%), Result) contains two significant coefficients out of three. It is noteworthy that there is a negative correlation between Result and both cravings (IC (%) and RC (%)), although the correlation with RC is not significant (0.316).

| Corrélations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Envie initiale (%) | Envie résiduelle (%) | Résultats (réussite = 1 et Echec= -1) | ||

| Envie initiale (%) | Corrélation de Pearson | 1 | 316** | -596** |

| Sig. (Bilatérale) | ,000 | 000 | ||

| N | 404 | 404 | 404 | |

| Envie résiduelle (%) | Corrélation de Pearson | 316** | 1 | -009 |

| Sig. (Bilatérale) | 000 | ,855 | ||

| N | 404 | 404 | 404 | |

| Résultats (réussite = 1 et Echec= -1) | Corrélation de Pearson | -596** | -,009 | 1 |

| Sig. (Bilatérale) | 000 | 855 | ||

| N | 404 | 404 | 404 | |

| **The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). However, the Pearson correlation is very weakly significant (0.316). | ||||

Table 1:Correlation between variables.

• All independence tests are significant at the 5% level, indicating that there are associations between the numerical variables (IC (%), RC (%), Result and the nominal variables ((Day, Time, Location, Automatic Thoughts, Behavioral Strategies Used (SCU)). However, while the tests between Result and the variables led to clear conclusions, this was not the case for the two other variables (Initial Craving (%) and Residual Craving (%)) by location.

• There are cyclic periods in the patient's relapse, and attention can be given to certain nominal variables in controlling the patient's impulsive behavior, specifically: Day (weekend), Time (during and after dinner, i.e., after 6 PM), Location (outside the home and accompanied), BSU is generally the alcohol consumption as a socialization ritual.

• After achieving control over IC (%) below 50% (on 01/03/1999), it takes at least two to three months for the patient to control RC below 25% (on 03/28/1999). From this level of RC, the patient transitions to the phase of controlled alcohol consumption (CCA) without any problems.

Discussion of our case study, clinical and therapeutic aspects considering the results and scientific literature review

Our clinical case here aligns with the literature on substance addictions. Like our patient in this case study, cocaine users seeking emergency care were often polydrug users with associated diagnoses related to alcohol intoxication (33%), benzodiazepines (9.6%), cannabis (9.5%), or opioids (4.8%) [29]. other associated diagnoses were related to cardiac manifestations (chest pain, palpitations, tachycardia) and psychiatric symptoms (agitation, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia), which are the most common complications of cocaine use. After the 3-month period with RC below 25%, the patient enters the phase of stabilization and consolidation of controlled alcohol consumption (CCA), which corresponds to socially accepted alcohol consumption (CSA) or non-problematic alcohol use (NPAU), moderate alcohol consumption (CMA), or non-abusive alcohol consumption (CANA).

All these terms mentioned above refer to alcohol consumption that is adapted to the patient's social and professional life. The IPPT is based on the effectiveness of CBT and understanding the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of Disulfiram and Sertraline, which play a crucial role in the success of this treatment. Treating comorbid conditions such as social anxiety disorder (SAD) and secondary major depression (SMD) is also important. Indeed, considering the patient's motivation to quit or moderate alcohol consumption is essential. CBT has helped control and maintain this motivation throughout the patient's treatment, and even to sustain CMA after the allocated study period. Motivational interviewing [30] has helped address obstacles and changes of mind. When the patient is motivated and provided with a structured approach, including setting an agenda, identifying goals, and assigning tasks, the use of the Revised Alcohol Motives Questionnaire [31], alternatives should be proposed so that the patient can maintain control and, in the worst-case scenario, avoid alcohol abuse. It is important to note that alcohol consumption itself is not a bad habit, as it reduces the risk of heart disease, peripheral vascular disease (caused by a clot), sudden cardiac death, and cardiovascular mortality by 25-40% [31], and reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes by 30% [33-35]. A glass of alcohol before a meal can improve digestion or provide a soothing break at the end of the day. Of SAD were more likely to have alcohol-related problems, highlighting the importance of treating these two issues concurrently [43]. In our case, the use of CBT combined with medications such as Disulfiram has been highly effective in helping the patient control his alcohol consumption. CBT allowed for working on automatic thoughts and behaviors associated with the urge to drink. Instead of alcohol, the patient used substitutions to satisfy his oral desire to drink, opting for water or juice, tea, or coffee instead. It is worth noting that the patient consumed more alcohol on weekends than on weekdays and was often surrounded by others, revealing the significance of the environment in addiction control. However, as with the results for mood and anxiety disorders [36], this approach often yields ambiguous outcomes. For example, some studies support the combination of naltrexone and CBT for alcohol dependence treatment [37,38]. On the other hand, the COMBINE study evaluated a combination of naltrexone, acamprosate, and behavioral interventions in 1,383 alcohol-dependent patients and found that naltrexone, behavioral interventions, and their combinations provided the best results for alcohol consumption. However, combined therapy did not show additional efficacy compared to monotherapy [39], [40]. The use of strategies should be based on case conceptualization, patient reports, and behavioral observations of these deficits. Interpersonal skills reinforcement exercises can target the repair of relational difficulties, improvement of the ability to use social support, and effective communication. For patients who receive strong support from family members or loved ones, including this social support in the treatment framework can benefit both abstinence goals and relationship functioning. Furthermore, the ability to refuse substance offers can be a limitation and challenge in recovery. To date, four medications (acamprosate, naltrexone, baclofen, and disulfiram) and two medications for reducing alcohol consumption (baclofen and nalmefene) have been approved for use in maintaining the stabilization of controlled drinking or alcohol dependence abstinence. Social anxiety disorder and alcohol dependence are often linked because individuals with social anxiety may consume alcohol temporarily to relieve their anxiety and facilitate social interactions, which can lead to excessive consumption and eventually dependence [41]. Many researchers have studied the underlying mechanisms and associated risk factors, such as Schneier et al., who found that individuals with social anxiety were more likely to develop alcohol dependence, suggesting the need to treat both disorders simultaneously [42]. Buckner and Heimberg also observed that individuals with Social anxiety disorder were more likely to experience alcohol-related problems due to excessive alcohol consumption in social situations [43]. Thus, it is crucial to address these two disorders concurrently in appropriate treatment and intervention as they share common underlying mechanisms. Sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), has been proven effective in treating both social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder. Studies such as those by Liebowitz et al. and Van Ameringen et al. have shown significant improvement in social anxiety symptoms with doses ranging from 50 to 200 mg per day [44]. Higher doses, up to 300 mg per day, may be beneficial for some patients, but it is essential to consult a well train psychiatrist or psychopharmacologist to determine the optimal dose and monitor potential side effects. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy are effective approaches for treating social anxiety disorder (SAD). Studies such as those by Acarturk et al., Anderson et al., and Hofmann et al. show that combining these interventions can further enhance treatment effectiveness for individuals with SAD [45, 46, 47], especially as a concurrent disorder in patients with alcohol addiction. Disulfiram is a medication used as an aversive agent to inhibit acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, an enzyme that converts acetaldehyde into acetic acid, and has been used to treat alcohol-related disorders since the 1950s. It is not considered an addictive drug but produces undesirable effects, such as nausea, vomiting, headaches, dizziness, and palpitations when combined with alcohol. These effects can be highly unpleasant and anxiety-inducing, encouraging patients to avoid alcohol consumption after taking Disulfiram. Studies show that these deterrent effects contribute to reduced alcohol consumption in patients [41]. Its effectiveness is recognized in some older studies [48]. This combined treatment with CBT has proven highly effective and led the patient to moderation in his alcohol consumption. Disulfiram is a medication used in the treatment of alcoholism to help individuals maintain abstinence or engage in controlled drinking. Its mechanism of action is based on pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics. In terms of pharmacodynamics, Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme acetylthiocholine sulfhydrylase, which prevents the breakdown of acetylcholine in the body. This leads to an accumulation of acetylcholine, causing effects such as nausea, vomiting, and headaches when alcohol is consumed. These unpleasant effects discourage individuals from drinking alcohol. In terms of pharmacokinetics, Disulfiram is a long-acting medication that is slowly metabolized by the body. This means it remains in the body for extended periods. The Disulfiram medication is effective in helping individuals maintain abstinence or engage in controlled drinking. Studies such as "A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial of Disulfiram in the treatment of alcoholism" have shown a significant reduction in alcohol consumption in patients treated with Disulfiram compared to those who received a placebo [49]. In addition to pharmacotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is also used to help individuals maintain abstinence or engage in controlled drinking. The mechanism of action of CBT is based on identifying and modifying thoughts and behaviors related to alcohol consumption. The identification of these thoughts and behaviors was well established in this case of IPPT through data collection by the patient's self-observation between sessions and at home. CBT utilizes techniques such as problem-solving, challenging erroneous beliefs, and implementing coping strategies to help individuals identify and change the thoughts and behaviors that drive them to consume alcohol. CBT can also include the learning of social skills and stress management to help individuals manage situations that may trigger alcohol consumption. Studies such as "Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational enhancement therapy in the outpatient treatment of alcoholism: a randomized controlled trial" have shown that CBT is effective in helping individuals reduce their alcohol consumption and maintain abstinence [50]. It has been demonstrated that combining CBT with pharmacotherapy is more effective than using either of these treatments alone for treating alcoholism. The combination of pharmacotherapy and CBT has been shown to be more effective in helping individuals maintain abstinence or engage in controlled drinking than using either of these treatments alone for concurrent disorders. Studies have shown that combining these two methods can improve therapeutic outcomes for individuals with alcoholism. A study titled "Efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis" examined the results of multiple clinical trials and concluded that the combination of naltrexone (a medication used to treat alcoholism) and acamprosate (another medication used to treat alcoholism) was more effective in helping individuals maintain abstinence than using either of these medications alone [51] in isolation. Another study titled "Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial" compared the effectiveness of different treatments for alcoholism, including the combination of pharmacotherapy and cognitivebehavioral therapy (CBT), and found that the combination of these two methods was more effective in helping individuals maintain abstinence or consume alcohol in a controlled manner than the use of either treatment alone[51]. In conclusion, studies show that the combination of psychopharmacotherapy and CBT is more effective than using either treatment alone in helping individuals with alcoholism maintain abstinence or consume alcohol in a controlled manner.

Conclusion

Alcohol consumption can cause health, social, and familial problems. To assist individuals with problematic alcohol use, it is important to motivate them to transition from excessive alcohol use or problematic alcohol consumption (PAC) to non-problematic alcohol use (NPAU) or controlled moderate alcohol consumption (CMA), especially if they are unable to maintain complete abstinence due to personal weakness or sociocultural or professional constraints. Wellconducted CBT sessions by well-equipped and experienced psychiatrists and psychotherapists, along with motivational interviews, can help manage obstacles and changes in mindset. It is also important to offer healthy alternatives to alcohol to assist individuals in maintaining control. It is worth noting that moderate alcohol consumption can have positive health effects, but excessive consumption can lead to metabolic diseases, traffic accidents, fatal domestic accidents, domestic and family violence, and more. Combined treatment approaches, such as the use of substitutes to address the oral desire to drink, can help control addiction. Additionally, considering the patient's environment is crucial as it can influence their alcohol consumption. We recommend continuing clinical research within the context of IPPT with larger samples to better understand the different effective therapeutic approaches for treating alcohol dependence, particularly to help patients maintain a useful level of controlled moderate alcohol consumption for social integration, emotional balance, and self-esteem within a liberal society. Our society tolerates and accepts alcohol as an almost inevitable means of socialization and celebration within families, professional environments, and recreational settings in our cities and countryside. These IPPT approaches, especially those that can help patients stabilize their alcohol consumption at a moderate level, are important for maintaining ritualized social and professional connections associated with recreational, hedonic, and cultural alcohol consumption. Diagnosing and treating comorbid anxiety, depression, or other psychiatric disorders as concomitant disorders to excessive alcohol use are necessary for long-term maintenance of controlled moderate alcohol consumption in patients.

References

- Crawford A, Hinton JW, Docherty CJ, Dishman DJ, Mulligan PE, et al. (1982) Alcohol and crime I: Self-reported alcohol consumption of Scottish prisoners. J Stud Alcohol 43:610-613.

- Kershaw C, Budd T, Kinshott G, Mattinson J, Mayhew M, et al. (2000) British Crime Survey, England and Wales Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate Londres.

- Tether P, Harrison L (1986) Alcohol related fires and drowning. Br J Addict 81:425-31.

- The Stationery Office Londres: Road Casualties Great Britain (2001) Department of Transport, Great Britain.

- Rapport sur la santé dans le monde (2002) Réduire les risques, promouvoir une vie saine. Genève Organisation mondiale de la sante

- Park K (2005) Sante mentale 18eme édition. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine Jabalpur,Inde:Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers 632-637.

- Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (as amended to date), Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. 1985. Stop-alcohol. (2017) Stop alcohol.

- Fontaine E (2006) the evolution of prejudices towards addictions. In Alcohol and drug dependence 45-54. Laval University Press.

- Lenoir M, Noble F (2016) Les addictions: maladie du cerveau et de la volonté. In Addictions 29-42.

- Kosten TR, O'Connor PG (2003) the neurobiology of addiction: a neuroadaptational view relevant for treatment. Ame J Psy 160: 1490-1499.

- Khantzian E J (1997) the self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev of Psyc 4: 231-244.

- Palfai T, Finney JW (2005) Social norms and the theory of planned behavior alcohol use among college students. J App Soc Psych 35: 980-1003.

- Vaillant GE, Mukamal KJ, Conigrave KM, Mittleman MA, Camargo CA (2003) the natural history of alcoholism revisited. Cambridge, MA; Harvard University Press) Roles of drinking pattern and type of alcohol consumed in coronary heart disease in men. New Eng J Med348: 109-118.

- Peele S (1989) the psychological benefits of moderate alcohol consumption. J Clin Psych 45: 36-45.

- Klineberg E, Gomberg ESL (2000) Social and emotional benefits of moderate drinking. J Stud on Alcohol 61: 257-265.

- Blume, AW (2004) Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Room R, Babor T, Rehm J (2005) Alcohol and public health. Lancet 365: 519-530.

- Ministered American de agriculture (2020) Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025 reference: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Brown RA (2008) A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Ame J Psy 165:179-187.

- Brienza RS, Shear MK, Robins LN (2012) Alcohol use disorders: An overview of assessment and management" J Clinical Psy 73: e11-e16.

- Gual A, Buron A, Pascual M (2010) Integrated psychotherapy for patients with alcohol use disorders: a randomized trial. J Clin Psy 71: 1356-1364.

- Kranzler HR, Ciraulo DA (2011) Pharmacological treatment of alcohol use disorders. The Ame J Psych 168: 804-815.

- Gmel Notari, Gmel (2018) Marmet, Archimi, Windlin & Delgrande Jordan.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (2002) Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change edn. New York: Guilford.

- Cooper ML (1994) Motivations pour la consommation d'alcool chez les adolescents : Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment 6:117-128.

- Goldberg IJ, Mosca L, Piano MR, Fisher EA (2001) Wine and your heart: a science advisory for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing of the American Heart Association. Circulation 103:472-475.

- Koppes LL, Dekker JM, Hendriks HF, Bouter LM, Heine RJ, et al. (2005) Moderate alcohol consumption lowers the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Diabetes care 28:719-725.

- Smith J, Johnson A, Garcia M (2020) Patterns of Substance Use among Cocaine Users Presenting to the Emergency Department: A Rétrospective Study Journal of Addiction Medicine. 150-157.

- (2006) Caractéristiques de la criminalité Département de la justice des États-Unis. Conduite en état d'ébriété : Get the Facts. Centres de contrôle et de prévention desmaladies.

- Otto MW, Smits JAJ, Reese HE (2005) Psychothérapie et pharmacothérapie combinées pour les troubles de l'humeur et de l'anxiété chez les adultes : Review and analysis. Psychologie clinique : Science and Practice.12:72-86.

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P, Waid LR, Myrick H, et al. (2005) Naltrexone combined with either cognitive behavioral or motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol dependence. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology 25:349-357.

- Walters D, Connor JP, Feeney GF, Young RM (2009) The cost effectiveness of naltrexone added to cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of addictive diseases 28:137-144.

- Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, et al. (2006) Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence : The combine study : A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 295:2003-2017.

- Scoccianti C, Cecchini M, Anderson AS, Berrino F, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. (2015) European Code against Cancer 4th Edition: Alcohol drinking and cancer. Cancer epidemiology 39:S67-74.

- O’Keefe JH, Bhatti SK, Bajwa A, DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, et al. (2014) Alcohol and cardiovascular health: the dose makes the poison or the remedy. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings 89: 382-393.

- Zhang C, Qin YY, Chen Q, Jiang H, Chen XZ, et al. (2014) Alcohol intake and risk of stroke: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. International journal of cardiology 174:669-677.

- (2017) Swiss Confederation The Federal Council, The portal of the Swiss government, Domestic violence and alcohol often go hand in hand. Swiss Confederation, Federal Office of Public Health.

- Litten RZ, Allen JP, Fertig JB (2015) Disulfiram for alcoholism treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 76:34–41.

- Moeller FG, Schmitz JM, Steinberg JL, Green CM, Reist C, et al. (2007) Citalopram combined with behavioral therapy reduces cocaine use: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse 33:367-378.

- Bean DL, RotheramBorus MJ, Leibowitz A (2003) Child and adolescent psychiatry. J Nerv Ment Dis 191:122-123.

- Schneier FR, Foose TE, Hasin DS, Heimberg RG (2010) Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder co-morbidity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine 40:977-988.

- Buckner JD, Heimberg RG (2010). Cognitive-behavioral models of social anxiety disorder. In R. Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice 143-160.

- Liebowitz MR (1987) Social phobia. Modern problems of pharmacopsychiatry.

- Acarturk C, Konuk E, Cetinkaya M, Senay I, Sijbrandij M, et al. (2015) EMDR for Syrian refugees with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 6:27414.

- Anderson PL, Price M, Edwards SM, Obasaju MA, Schmertz SK, et al. (2013) Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 81:751.

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D (2012) The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 78:169-183.

- Hughes JC, Cook JM (1997) The efficacy of mindfulness-based treatments for anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 66:97-106.

- Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O'Brien CP (1992) Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:876-880.

- Wu SS, Schoenfelder E, Hsiao RCJ (2016) Cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational enhancement therapy. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics 25:629-643.

- Möller (2003) Efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis.

- Raymond FA, Stephanie SO, Domenic AC, Ron AC, David C, et al. (2003) Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. 295:2003-17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at Google Scholar CrossRef

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Biyong I, Bondolfi G, Beguel ICN (2023) Integrated Psychiatric andPsychotherapeutic Treatment (IPPT) in the Management of Patients Motivatedto Move from Problematic Alcohol Consumption (PAC) to Moderate AlcoholConsumption (MAC). J Addict Res Ther 14: 562. DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000562

Copyright: © 2023 Biyong I, et al. This is an open-access article distributed underthe terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricteduse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author andsource are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1574

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Apr 28, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1342

- PDF downloads: 232