Influence of Socio-Demographic Characteristics on Use of Skilled Delivery Services (SDS) at Health Facilities by Pregnant Women in the Central Region of Ghana

Received: 03-Dec-2018 / Accepted Date: 22-Jan-2019 / Published Date: 29-Jan-2019 DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000403

Abstract

Introduction: The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on use of Skilled Delivery Services (SDS) at health facilities by pregnant women in the central region of Ghana.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study design was used to conduct the study. A stratified sampling technique was used to select a sample of 1100 pregnant women. Structured questionnaire was used to collect the data and analyzed using frequencies, percentages and binary logistic regression where missing values were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations.

Results: The sociodemographic factors that determine the use of SDS were religion (OR=1.70, 95% CI=1.11-2.58, p=0.015) and person in authority who takes decision on where a person should deliver (OR=2.60, 95% CI=1.61-4.39, p=0.0004) and having valid national health insurance (OR=1.78, 95% CI=1, 06-3.00, p=0.030).

Conclusion: In conclusion, more need to be done to address the issue of minority Muslim communities in the Central Region by providing cost effective and easy access to health facility within those communities, place more emphasis on facility delivery education, and counselling. Women need to be empowered to be independent in taking decision regarding health facility delivery.

Keywords: Delivery; Health facility; Pregnant women; Utilization

Introduction

The contribution of women in the welfare of families, communities and countries in terms of ensuring better health cannot be underestimated [1]. Due to the important roles’ women play for the improvement and development of the economy, their health care during pregnancy is of importance in all countries of the world [1]. The death of mothers threatens the survival and wellbeing of children in the family [2]. When a mother dies during childbirth, there is high probability of the baby also dying within two years [2]. When children who are up to 10 years, lose their mothers, the children are 3 to 10 times more likely to also die within two years than children whose mothers are alive [2]. The use of Skilled Delivery Service (SDS) is an intervention proposed by World Health Organization (WHO) to help reduce Maternal Mortality (MM) and under five mortality [3].

Factors that determine utilisation of health services by women include age, birth order, religion, residence, ethnicity, education, family size, income, occupation, parity and others [4-6]. This indicates that background characteristics of pregnant women influence their use of SDS. The authors concluded that pregnant women who are less than 25 years are less likely to use Skilled Birth Attendant (SBA) (OR=0.31, 95% CI=0.16-0.62) compared with those who are 26 years and above. On the other hand, majority (74%) of the women who are 34 years and below use SDS at health facilities in Ghana compared with the women who are 35 years and above (70%) [4].

Mother’s age may sometimes serve as a proxy for the woman’s accumulated knowledge of health care services which may have a positive influence on the use of health services. Young women (OR=0.468, p=0.046), and older women and their husbands with lower educational background (OR=0.391, p=0.007), and women who live far from health facilities (OR=0.457, p=0.011) are less likely to use SDS at health facilities [7]. Income level determines the amount of money available for individuals and family and their ability to afford health care [5,8]. Income level of women has greater influence on the use of maternal health services [9]. Women in high-income countries are more likely to use SDS than women in low-income countries [10]. A study in Central District, Kitui County, Kenya, it was concluded that monthly household income (OR=1.73, p=0.018) affect the use of SDS by pregnant women [11]. In a similar study done in Indonesia, it came to light that physical distance and financial limitations of the women were the two major factors that prevent them from using SBAs and to deliver at health facilities [12].

Family resources such as income, ownership of active health insurance and location of residence influence the use of maternal health care [13]. The kind of work the women and their husbands do determines the amount of money available for them to spend on their needs including health care [9]. Husband’s occupation can be considered a proxy of family income, as well as social status. Differences in attitudes to modern health care services by occupational groups depict occupation as a predisposing factor. Women’s power to make decision is a key factor as far as the use of maternal health care is concerned [14]. Factors that are likely to enable women to use SDS are women’s autonomy and social standing [15]. It was revealed in a study that women, who are more likely to use the services of SBAs during pregnancy and delivery, either at the health facilities or at home, are those who own some aspects of family resources [16]. These women most of the time do not need the permission of their husbands before they seek health care. When a woman has control over the economic resources of the family, she is able to make decisions at any time as to how the money will be used. According to a study in a north Indian city, women who have the freedom to move out from their households are 3 times more likely to use Antenatal Care (ANC) and quality delivery services than women who face restrictions about their movement [17]. It was concluded in a study conducted at Nepal that the status of women in society; women’s involvement in decision-making; and women’s autonomy have high influence on their use of SDS at health facilities [18]. Decision-making regarding access to and use of skilled maternal healthcare services is strongly influenced by the values and opinions of husbands, mothers-in-law, traditional birth attendants and other family and community members, more than those of individual childbearing women [19,20].

Methods

Aim, design and setting of the study

The purpose of this study was to assess influence of sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant women on utilization of skilled delivery services in Central Region of Ghana.

The study was a descriptive cross-sectional survey that quantitatively explored the proportion of utilisation of SDS in the Central Region of Ghana. The study focuses on health facilities in the selected districts in the Central Region of Ghana. The region shares borders on the east with the Greater Accra Region, on the north with Ashanti Region and on the north-east with Eastern Region. The region has 20 administrative districts with the historical city of Cape Coast as the capital. About 63% of the region is rural [21]. The population was estimated at 2,413,050 for the year 2013 with an annual growth rate of 3.1% and a population density of about 215 inhabitants per square utilisation [21].

Population

The target population for the study was pregnant women of reproductive age, between 15-49 years who had delivered within the past three years prior to the study regardless of their birth outcome and those who had never given birth and are pregnant for the first time, in the Central Region of Ghana.

Sampling procedure

Sample size of 1,100 pregnant women was used. This was arrived at with the use of Krejcie and Morgan’s sample size estimation formula and 10% non-response rate, with design effect of 2, to compensate the clustering effect introduced as a result of stratified sampling technique used [21].

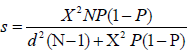

Krejcie and Morgan (1970) formula was used in calculating the sample size. It is given as:

where,

s=required sample size.

X2=the table value of chi-square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841).

N=the population of ANC clients in the selected health facilities.

p=the population proportion (assumed to be 0.50 since this would provide the maximum sample size).

d=the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (0.05).

After the calculation, the sample size was 385. Assuming 10% non-response rate, design effect of 2, (to compensate the clustering effect introduced as a result of using stratified sampling technique) the sample size was:

N=385 х 2+10% of 770=770+77=847

This brought the estimated sample size to 847 and this was rounded up to a sample size of 1100. This is because as the sample size increases, the result becomes more accurate. Pregnant women between the ages of 15-49 years and those who have ever given birth had their last delivery in the Central Region were included in the study. Pregnant women who gave birth more than 3 years prior to the study and those who gave their last delivery outside the study area were excluded.

The districts in the region were grouped into two strata, urban and rural. The purposive sampling method was used to select public health facilities that provide ANC services within the selected districts such as hospitals, poly clinics, health centers and Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) compounds. Simple random sampling technique was used to select 10 districts out of the 20 districts. That is 6 districts with hospitals and 4 districts without hospitals. This was to make the sample representative of the 12 districts that had hospitals and 8 districts that did not have hospitals. The simple random sampling method was also used to select 2 health facilities that provide ANC services from each of the selected districts, one from urban and one from rural area. The simple random sampling method gave every facility a fair chance of being selected to help determine the utilisation of SDS at the selected health facilities to inform appropriate intervention. The proportionate stratified sampling method was used to select the respondents in proportion to the size of the population in their study area.

The purposive and convenient sampling method was also used to select 1,000 women with their first pregnancy and those who had their last delivery within the past three years prior to the study.

Data collection instrument

Questionnaire for socio-demographic characteristics of respondents and SDS utilization scale of measure was used to collect the data. The questionnaire was adapted from the safe motherhood questionnaire developed by maternal and neonatal health programme of Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynecology and Obstetrics (JHPIEGO) and Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS) [22]. The questionnaire was developed in English and later translated into Fante to make it more cultural relevant and comprehensive to the participants. This is because most of the people in the Central Region of Ghana are Fantes and the translation of the questionnaire also enhances content validity and gathers rich data. Each participant completed a set of standard demographic questionnaires designed for the present study. The information collected centered on participants’ age, religion, marital status, level of education of mother and husband, decision maker, ownership of National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), average monthly income and occupation. A pre-test or preliminary trial of the instrument was conducted at one health facility in the Western Region to ensure clarity of the questions and to correct confusion over some items of the instrument before the actual fieldwork. In addition, the questionnaire was piloted to establish the time needed to complete the survey and to screen the questions. The responses from the pregnant women were collated and used to determine the reliability of the instrument. The reliability of the items on the questionnaire was determined separately with the use of the Cronbach’s alpha. The reliability of each of the three factors was established using Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of internal consistency. The test has a reliability of 0.85 (F1-internal), 0.88 (F2-exaggerated) and 0.97 (F3-mediator). The BPCS has been found to have excellent construct validity with a range of 0.85-0.95.

The items on the instrument were reviewed by the supervisors, colleagues and other experts in SDS use for scrutiny, corrections, readability, clarity and comprehensiveness for face and content validity. To determine reliability of the instrument, the validated version of the questionnaire was pretested with 100 pregnant women who consented to the pretest at one hospital in the Western Region. The Cronbach’s Alpha for the pretest instrument was 0.905 for the pre test instrument with 75 items. In the case of the actual study, the 1100 questionnaires with 74 items on each questionnaire, the scale had good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.921. This implies that the items on the questionnaire correlate to each other. Cronbach’s Alpha is an index which is used to determine the reliability of the data collection instrument [23].

Data collection procedure and ethical issues

Ethical clearance for the study was sought from the University of Cape Coast Ethical Review Board and Ghana Health Service, Ethics Review Committee. Approval for the study was sought from the Central Regional Health Directorate and permission was sought from the District Health Directors, Medical Superintendents, and the in-charges of the selected districts, health facilities and ANC clinics respectively. The purpose of the study was explained to the clients. Six research assistants were trained and supported the data collection that is five Community Health Nursing trainees and one ANC clinic incharge. The use of the research assistants facilitated the data collection. Participants who could not read and/or write were asked to thumb print as approval for informed consent after the purpose of the study was explained and they were informed about their right to interrupt the interview at any time or opt out of the study without any fear of future prejudice. This was achieved by giving them informed consent forms to fill. The questionnaires were distributed to those who consented to participate in the study and the instruments were taken right after completion. Respondents were assured of confidentiality. The principal researcher was in full control over the data collection. This also ensured that the data were collected as planned.

All information obtained from the participants were kept confidentially. The names of respondents were not associated with responses provided to ensure their anonymity. Participants were informed about their freedom to skip some of the questions and exit from the study. The participants were informed about the duration (20 min) for answering the questionnaire.

Data processing and analysis

After removing data from incomplete questionnaires, we evaluated the assumptions underlying parametric tests using Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS). Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyse the data. The data collected were screened to ascertain the accuracy of the data, deal with missing data, and assess the effects of extreme values on the analysis. The dependent variable, utilisation of SDS, was dichotomous, implying that a pregnant woman in labour would use SDS or not. To determine the use of SDS among the pregnant women descriptive statistics was done to summarise and describe the data. The frequencies provided information about the number of participants who responded to each item. Consideration was given to the dichotomous (whether client will use SDS at health facility or not) data. Pie chart and cross tabulations were used to present the data.

Results And Discussion

The results of the data analysed on the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on utilisation of SDS are shown in Table 1. The majority of pregnant women 55% (n=489) who intended to use SDS were between 20-29 years. On the religious faith of pregnant women and intention to use SDS, among those who intended and those who did not intend to use SDS, Christians were the majority, 87% (n=753) and 81.3% (n=170), respectively. More than two thirds of the married women, 69% (n=600) had the intention to use SDS. The majority of the respondents who intended to use SDS, 58% (n=509) and those who did not intend to use SDS, 66% (n=145), had basic education. Almost half, 49% (n=429) of the women who intended to use SDS, were married to husbands who had up to basic level education. Regarding who makes decisions for respondents about where they seek health care, 41% (n=355) of the women who intended to use SDS make their own decisions. The majority, 88% (n=778) of the pregnant women among those had the intention of using SDS and those who were not willing to use SDS, 80% (n=174) had active NHIS (Table 1).

| Socio-demographic predictors | Use of SDS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | B | Wald | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Age in years (n=1100) | 0.95 | 0.416 | |||||

| <20 | 15 (6.9) | 76 (8.6) | 1.95 | 0.78-4.90 | |||

| 20-29 | 115 (52.5) | 489 (55.5) | 1.180 | 1.64 | 0.77-3.49 | ||

| 30-39 | 79 (36.1) | 290 (32.9) | .354 | 1.41 | 0.65-3.05 | ||

| 40-49 | 10 (4.5) | 26 (3.0) | .391 | ref | |||

| Religion (n=1072) | 2.25 | 0.025 | |||||

| Islamic | 39 (18.7) | 110 (12.7) | ref | ||||

| Christianity | 170 (81.3) | 753 (87.3) | .551 | 1.58 | 1.06-2.37 | ||

| Marital status (n=1090) | 0.76 | 0.466 | |||||

| Never married | 24 (11.0) | 78 (9.0) | ref | ||||

| Married | 141 (64.7) | 600 (68.8) | .628 | 1.31 | 0.80-2.15 | ||

| Living together/cohabiting | 53 (24.3) | 194 (22.2) | .204 | 1.13 | 0.65-1.96 | ||

| Mothers level of education (n=1100) | 1.86 | 0.133 | |||||

| No formal | 26 (11.9) | 145 (16.4) | ref | ||||

| Basic | 145 (66.2) | 509 (57.8) | -.409 | 0.63 | 0.40-0.99 | ||

| Secondary | 28 (12.8) | 139 (15.8) | -125 | 0.89 | 0.50-1.59 | ||

| Tertiary | 20 (9.1) | 88 (10.0) | -.774 | 0.79 | 0.42-1.50 | ||

| Husband/partner’s level of education (n=1100) | 1.50 | 0.213 | |||||

| No formal | 27 (12.3) | 103 (11.7) | ref | ||||

| Basic | 119 (54.4) | 429 (48.7) | .066 | 0.95 | 0.59-1.51 | ||

| Secondary | 43 (19.6) | 176 (20.0) | .813 | 1.07 | 0.63-1.84 | ||

| Tertiary | 30 (13.7) | 173 (19.6) | .627 | 1.51 | 0.85-2.68 | ||

| Decision taker on where mothers should seek healthcare (n=1088) | 6.18 | 0.001 | |||||

| Family member | 46 (21.2) | 90 (10.3) | ref | ||||

| Husband/partner | 56 (25.8) | 275 (31.6) | 1.665 | 2.50 | 1.58-3.95 | ||

| Self | 77 (35.5) | 355 (40.8) | .379 | 2.35 | 1.52-3.62 | ||

| Husband/partner and self | 38 (17.5) | 115 (17.3) | .263 | 2.00 | 1.21-3.31 | ||

| Ownership of NHIS (n=1100) | 2.17 | 0.030 | |||||

| Not valid | 22 (10.0) | 52 (5.9) | ref | ||||

| Valid | 197 (90.0) | 829 (94.1) | 1.254 | 1.78 | 1.06-3.00 | ||

| Average monthly income in cedis (n=566) | 0.69 | 0.502 | |||||

| ≤ 100 | 56 (42.4) | 167 (38.5) | ref | ||||

| 101-200 | 18 (13.6) | 86(19.8) | .265 | 1.36 | 0.78-2.36 | ||

| >200 | 58 (44.0) | 181(41.7) | .044 | 1.18 | 0.79-1.75 | ||

| Model performance measures | |||||||

| AUROC | 66.6% | ||||||

| Hosmer-Lameshow GOF test | X2=6.16, p=0.6294 | ||||||

| AIC | 577.24 | ||||||

Table 1: Effect of socio-demographic characteristics on use of SDS.

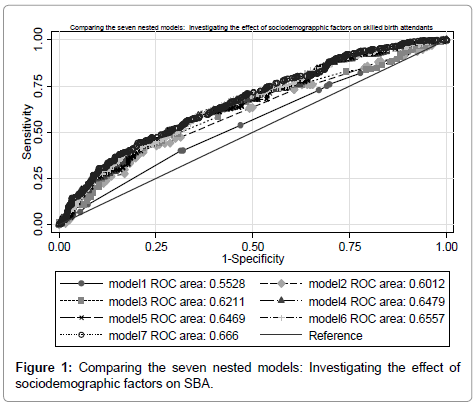

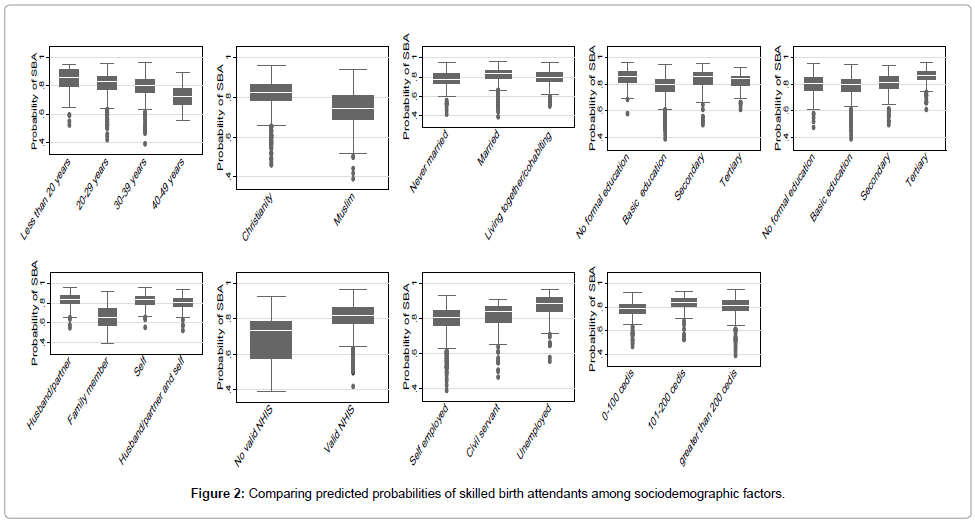

In investigating the effect of socio-demographic factors on the proportion of skilled delivery at birth, seven different nested models comprising mainly sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants were assessed and evaluated with Area under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). There was statistical significance difference in AUROC among the 7 nested models (X2=738.44, p<0.0001). The best performing model was model 7 (AUROC=66.60%, AIC=34491.48). Detailed evaluation of the 7 models can be found in Table 2. Graph depicting the performance of the models and prediction of SBA use could be found in Figures 1 and 2 respectively. Overall the logistic regression model was significant at -2Log l=463.021, Nagelkerke R2=.239, X2=92.92, p=0.000. The correct prediction rate was about 92.6%. The multivariable logistic regression analysis based on model 7 in Table 1 shows that religion, ownership of valid NHIS and the person in authority who takes decision on where mothers should deliver their babies are associated with the use of SDS. The odds of a Christian using SDS is approximately 1.6 (OR=1.58, 95% CI=1.06-2.37, p=0.025) times higher than the odds of a Muslim. The odds of a pregnant woman using SDS is 2.5 (OR=2.50, 95% CI=1.58-3.95, p=0.001) times higher if the decision to deliver in a recommended health facility was made by husband of the woman compared to it being supported or recommended by a family member. Pregnant women who had valid NHIS were 1.8 (OR=1.78, 95% CI=1.06-3.00, p=0.030) time more likely to use SDS than women who had invalid NHIS (Table 2) (Figures 1 and 2).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Age | Age | Age | Age | Age | Age | Age |

| Religion | Religion | Religion | Religion | Religion | Religion | Religion | |

| Marital status | Marital status | Marital status | Marital status | Marital status | Marital status | Marital status | |

| Mothers education | Mothers education | Mothers education | Mothers education | Mothers education | Mothers education | ||

| Partners education | Partners education | Partners education | Partners education | Partners education | |||

| Decision taker | Decision taker | Decision taker | Decision taker | ||||

| NHIS membership | NHIS membership | NHIS membership | |||||

| Monthly income | Monthly income | ||||||

| Mothers occupation | |||||||

| Model performance index | |||||||

| AUROC (95% CI) | 55.28% (54.56-56.06) |

60.12% (59.43-60.81) |

62.11% (61.43-62.79) | 64.79% (64.10-65.49) | 64.69% (64.01-65.39) |

65.57% (64.88-66.26) |

66.60% (65.92-67.29) |

| AIC | 36894.15 | 36402.53 | 36125.79 | 35508.75 | 35495.87 | 34859.69 | 34491.48 |

| HL GOF | χ2=55.77, p<0.0001 | χ2=123.00, p<0.0001 | χ2=453.71, p<0.0001 | χ2=181.04, p<0.0001 | χ2=457.29, p<0.0001 | χ2=192.78, p<0.001 | χ2=272.34, p<0.0001 |

AUROC: Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve; AIC: Akaike Information Criterion; HL GOF: Hosmer Lameshow Goodness of Fit Test

Table 2: Evaluating the predictive performance of the seven nested model.

The finding that religion is associated with use of SDS supports the findings of cross sectional descriptive studies conducted in Bangladesh in East India, Ga East in Ghana and Sub Saharan Africa [24-26]. The similarities could be due to the research design and the population of the study used for the current. Another possible explanation could be that all the studies were done in developing countries which have the same socio-economic characteristics.

Religious affiliation may not change over time but there is the possibility that maternal education, occupation and monthly income of mothers have changed over the 3-15 year period between these studies, which could be attributed to the individual effort and government interventions, and for that matter they no longer have effect on SDS use with the current study. A systematic review highlighted the important role religious beliefs play in determining where a woman delivers in Nepal and they recommended the use of qualitative design to explore why and how religion is responsible for SBAs during delivery [27].

In Ghana, most Muslims live in the slum areas and are generally considered to be poor with low-moderate level of education [4]. This accounts for the recent decision by the Government of Ghana to develop such areas through the Zongo Development Fund. Their inability to perhaps pay for hospital delivery charges may account for why most of them seek the services of TBAs which are relatively cheaper and easily accessible within the communities. It could also be due to the fact that Muslims mostly believe in herbal medicines for pregnant women during and after labour which are not provided at health facilities by SBAs. Most of the Muslim dominated Zongo communities do not have health facilities located within the reach of the masses and that might have also contributed to why few of them delivered in health facilities [28]. It was emphasized by a study in Guatemala that certain ethnic or religious groups may be discriminated against by staff of health facilities, making them less likely to use SDSs available to them [29]. The study findings are also supported by a study in Rwanda that found members of traditional religions and Muslims to be less likely to use delivery services as compared to Christians [16]. Based on a similar cross-sectional study where SBA was modeled through logistic regression analysis, it showed that Muslim women in rural India were less likely to benefit from SDS.

In rural Ghana however, the findings from the study in the northern region contradict the findings on religious affiliation and its relationship with SDS use [30]. In another study, no statistically significant relationship was found between ethnic and religious differentials. It was proved that mothers from minority religious groups similar to Muslims in Ghana were 1.8 times more likely to use SDS compared to the majority religious groups which is a sharp contrast to the current findings [31].

Women and husband autonomy in deciding where to deliver has long been linked to SDS as was the case in this study [32-35]. Women who are involved in taking key decisions of the house are normally well educated, financially independent or hold key position in society. These attribute result in higher probability of delivering in health facilities as those women are more likely to be aware of the risk of delivering without the assistance of SBA.

Age of mothers is in most cases treated as a confounder in multivariable studies investigating the effect of socio-demographic factors on SDS. The findings from the current study indicated that mother’s age did not have effect on SDS use which contradicts the findings of a study in Sub Saharan Africa and Bangladesh where multivariate analysis was applied to establish whether there is evidence that teenagers have poorer SBA use than older women with similar background characteristics [36,37]. The present study did not support the findings of the similar cross-sectional studies where age at birth was related to place of delivery through multivariable logistic regression analysis [38,39].

However, the current study replicates the findings of the study in Bahi district in Tanzania which saw no statistically significant relationship between mothers’ age and place of delivery [40,41]. It could be inferred that as most of the young women in Ghana are unemployed, they are unlikely to afford SDS if they don’t have valid NHIS [4]. As a result, these young mothers could end-up delivering by Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) but the free maternal delivery intervention in Ghana is available to every woman independent of her age. This singular policy might have contributed to why age was not seen as a significant factor in SDS. Mass education carried out on several radio stations by governmental and non-governmental organisations on the consequences of delivering outside health facilities could have contributed to the larger proportion of individuals having the intension to deliver at health facilities with their current pregnancy.

Several authors have explained that husband and maternal education are consistently and strongly associated with all forms of maternal health outcomes and use of SDS. The findings of the study contradict studies conducted by other researchers [38,39,42-45]. Couples who are educated generally have increased knowledge of the benefits of seeking quality health care, understand the risk associated with unskilled birth attendants coupled with reduced power differential towards health care providers since they have the financial capabilities to pay for health service delivery bills.

In the current study, husband and maternal education were not found to influence SDS use and this replicates the findings of few studies that did not find statistically significant relation between SDS use and husband and maternal level of education [46,47]. The nationwide free maternal delivery policy may have played critical role in improving the use of SDS since there is no prior condition before one becomes beneficiary of the intervention.

The findings of the study corroborate that of studies conducted by other researchers where there is positive correlation between health insurance coverage and use of SDS [48-50]. The similarities were in line with the fact that all the studies were conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries. Mothers with valid NHIS membership card may generally end-up delivering in health facilities as certain cost of facility delivery are catered for by the insurance. A study in Rwanda confirmed that financial barriers may be lifted when women are insured and encouraged to deliver their babies in a health facility by SBAs [51]. However, having health insurance was not consistent with economic theory that health insurance coverage can reduce financial barriers to care and increase the probability of using SDS in this study. These findings could be attributed to the free maternal delivery policy which insists that all pregnant women must have valid NHIS membership card.

The findings of the study are in support of the Andersen’s Behavioural Model of Health Services Use. The model posits that predisposing factors (religion and decision maker) and enabling factor (health insurance coverage) facilitate the use of any available health service. The enabling factors are based on the argument that even if a family/individual has a predisposition to use health services, certain characteristics must be in place to enable them to access services. This confirms that religious affiliation of the pregnant women, the one who decides on where and when the women should seek health care and ability to afford the SDS in terms of owning valid NHIS are factors, which could strongly determine the woman’s intension to use SDS with current pregnancy. An individual's access to and use of health services is considered to be a function of predisposing factors of social structure and demographic parameters which include education, occupation, ethnicity, religion, social networks, social interactions, culture, access to health insurance, income and age [51]. This study investigated these predisposing factors and how they influence skilled delivery in health facilities across the Central Region. With the exception of religion, all other predisposing factors investigated were not related to institutional delivery. Most of Anderson’s predisposing factors are timevarying which shows that those characteristics might have had effect on skilled birth attendant some years back but may not necessarily be relevant predictor today especially when there are currently ongoing Government intervention (free maternal facility delivery policy) where sole inclusion criteria for enjoying benefits of the intervention is to be a Ghanaian woman independent of one’s highest education level, occupation, ethnicity, religion, social networks, social interactions, culture and age. The argument being advance is that although religious affiliation of an individual could also change over time, the propensity is low compared to other identified predisposing factors by Anderson which could still make religion a good predictor of SBA.

Religious leaders are considered influential persons in most of the communities in Ghana. Health care providers should organize meetings or seminars about interventions which an improved utilisation of SDS mostly among the Muslim women and the consequences of not using skilled assistance at delivery with these influence leaders [52].

Conclusion

The government and all stakeholders should provide interventions that will address the SDS issue of the Muslim communities in the Central Region by providing cost effective and easy access to health facilities within those communities. Future studies could also look at the views of family members and husbands with regard to determinants of use of SDS. Service providers could also be targeted about the same issue. Studies could be conducted on the effects of birth preparedness plan and its influence of the use of SDS. In addition, studies could be conducted on the SBAs to find out their views concerning SDS use at health facilities in the country by pregnant women.

Declarations

Ethical aspects and consent to participate

Authorization of the responsible hospitals and maternity hospitals was obtained before the start of the study. The oral consent, anonymity of the health care providers and the confidentiality of the data were respected.

Paper context

The investigated the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on use of skilled delivery services by pregnant women in the central region of Ghana. Data was collected from pregnant women at antenatal clinic. Religions, decision taker, valid national health insurance were factors that were found to influence the use of skilled delivery services at health facilities in the region.

Authors’ contributions

I conceived the study, the design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and write-up and in the preparation of the draft manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge all my mentors. I am highly indebted to various writers from whom references were made. I would like to thank all other individuals who provided the needed support for me to complete this study.

References

- World Health Organisation (2015) WHO recommendation on postnatal care for the mother and newborn. Geneva.

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), ICF International Ghana (2015) Demographic and Health Survey 2014: Key indicators report. Maryland, USA.

- Nzioki JM, Onyango RO, Ombaka JH (2015) Perceived socio-cultural and economic factors influencing maternal and child health: Qualitative insights from Mwingi District, Kenya. Ann Community Health 3: 13-22.

- Addai I (2000) Determinants of use of maternal-child health services in rural Ghana. J Biosoc Sci 32: 1-15.

- Oo K, Win LL, Saw S, Mon MM, Oo YTN, et al. (2012) Challenges faced by skilled birth attendants in providing antenatal and intrapartum care in selected rural areas of Myanmar. WHO South East Asia J Public Health 1: 467-476.

- Abor PA, Abekah-Nkrumah G, Sakyi K (2011) The socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilization in Ghana. Int J Soc Econ 38: 628-648

- Blackwell DL, Martinez ME, Gentleman JF, Sanmartin C, Berthelot JM (2009) Socio-economic status and utilization of health care services in Canada and the United States: Findings from a binational health survey. J Medical Care 47: 1136-1146.

- World Health Organisation, UNICEF (2014) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva.

- Kanini CM, Kimani H, Mwaniki P (2013) Utilisation of Skilled Birth Attendants among women of reproductive age in Central District, Kitui County, Kenya. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health 7: 80-86.

- Titaley RC, Hunter LC, Dibley JM, Heywood P (2010) Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery? A qualitative study on delivery care services in west java province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10: 43.

- Andersen R, Newman JF (2005) Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q 83: 4.

- Beegle K, Frankenberg E, Thomas D (2001) Bargaining power within couples and use of prenatal and delivery care in Indonesia. Stud Fam Plann 32: 130-146.

- Fapohunda BM, Orobaton NG (2013) When women deliver with no one present in Nigeria: Who, what, where and so what? PloS one 8: e69569.

- Gyimah SO, Takyi BK, Addai I (2006) Challenges to the reproductive health needs of African women: On religion and maternal health utilizations in Ghana. Soc Sci Med 62: 2930-2944.

- Bloom SS, Wypij D, Gupta MD (2001) Dimensions of women’s autonomy and the influence on maternal health care utilization in a north Indian city. Demography 38: 67-78.

- Baral YR, Lyons K, Skinner J, Teijlingen ERV (2010) Determinants of skilled birth attendants for delivery in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J 8: 325-332.

- Lowe M, Chen DR, Huang SL (2016) Social and cultural factors affecting maternal health in rural Gambia: An exploratory qualitative study. PloS One 11: e0163653.

- Ganle JK, Otupiri E, Parker M, Fitpatrick R (2015) Socio-cultural barriers to accessibility and utilization of maternal and newborn healthcare services in Ghana after user-fee abolition. Int J Matern Child Health 3: 1-14.

- Krejcie RV, Morgan DW (1970) Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas 30: 607-610.

- Barco RCD (2004) Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health. Maryland, USA. Maternal and Neonatal Health Program of JHPIEGO.

- Berrenberger JL (1987) The Belief in Personal Control Scale: A measure of God mediated and exaggerated control. J Pers Assess 51: 194-206.

- Shahabuddin A, Brouwere VD, Adhikari R, Delamou A, Bardaj A, et al. (2017) Determinants of institutional delivery among young married women in Nepal: Evidence from the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. BMJ Open 7: e012446.

- Esena RK, Sappor MM (2013) Factors associated with the utilization of skilled delivery services in the Ga East Municipality of Ghana Part 2: Barriers to skilled delivery. Inter J Scientific Technol Res 2: 195-207.

- Gyimah-Boadi E (2000) Civil society organizations and ghanaian democratization. CDD-Ghana. Pp: 1-37.

- Gabrysch S, Campbell OMR (2009) Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9: 34.

- Glei DA, Goldman N, RodrıÌguez G (2003) Utilization of care during pregnancy in rural Guatemala: Does obstetrical need matter? Soc Sci Med 57: 2447-2463.

- Hazarika I (2011) Factors that determine the use of skilled care during delivery in India: Implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. Mater Child Health J 15: 1381-1388.

- Sakeah E, Doctor HV, McCloskey L, Bernstein J, Yeboah-Antwi K, et al. (2014) Using the community-based health planning and services programme to promote skilled delivery in rural Ghana: Socio-demographic factors that influence women utilization of skilled attendants at birth in Northern Ghana. BMC Public Health 14: 344.

- Anwar I, Sami M, Akhtar N, Chowdhury M, Salma U, et al. (2008) Inequity in maternal health-care services: Evidence from home-based skilled-birth-attendant programmes in Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ 86: 252-259.

- Duong DV, Binns CW, Lee AH (2004) Utilization of delivery services at the primary health care level in rural Vietnam. Soc Sci Med 59: 2585-2595.

- Li J (2004) Gender inequality, family planning and maternal and child care in a rural Chinese county. Soc Sci Med 59: 695-708.

- Mrisho M, Schellenberg JA, Mushi AK, Obrist B, Mshinda H, et al. (2007) Factors affecting home delivery in rural Tanzania. J Tropical Med Int Health 12: 862-872.

- Nigussie M, Mariam DH, Mitike G (2004) Assessment of safe delivery service utilization among women of childbearing age in north Gondar Zone, North West Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 18: 145-152.

- Magadi MA, Agwanda AO, Obare FO (2007) A comparative analysis of the use of maternal health services between teenagers and older mothers in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Soc Sci Med 64: 1311-1325.

- Idris SH, Gwarzo UMD, Shehu AU (2006) Determinants of place of delivery among women in a semi-urban settlement in Zaria, northern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 5: 68-72.

- Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Ekholuenetale M (2017) Factors associated with the utilization of institutional delivery services in Bangladesh. PLoS One 12: e0171573.

- Reynolds HW, Wong EL, Tucker H (2006) Adolescents' use of maternal and child health services in developing countries. Int Fam Plan Perspect 32: 6-16.

- Wanjira C, Mwangi M, Mathenge E, Mbugua G, Nganga Z (2011) Delivery practices and associated factors among mothers seeking child welfare services in selected health facilities in Nyandura South District, Kenya. BMC Public Health 11: 360.

- Burgard S (2004) Race and pregnancy-related care in Brazil and South Africa. Soc Sci Med 59: 1127-1146.

- Gitimu A, Herr C, Oruko H, Karijo E, Gichuki R, et al. (2015) Determinants of use of skilled birth attendant at delivery in Makueni, Kenya: A cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15: 9.

- Kimani H, Farquhar C, Wanzala P, Nganga Z (2015) Determinants of delivery by skilled birth attendants among pregnant women in Makueni County, Kenya. J Public Health Res 5: 1-6.

- Samson G (2012) Utilization and factors affecting delivery in health facility among recent delivered women in Nkasi District. Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS).

- Dharmalingam A, Hussain T, Smith J (1999) Women's education, autonomy and utilization of reproductive health services in Bangladesh. Reproductive health: Programme and policy changes post-Cairo. Liege, Belgium.

- Raghupathy S (1996) Education and the use of maternal healthcare in Thailand. Soc Sci Med 43: 459-471.

- Brooks MI, Thabrany H, Fox MP, Wirtz VJ, Feeley FG, et al. (2017) Health facility and skilled birth deliveries among poor women with Jamkesmas health insurance in Indonesia: A mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 17: 105.

- Celik Y, Hotchkiss DR (2000) The socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilization in Turkey. Soc Sci Med 50: 1797-1806.

- Mills A, Ally M, Goudge J, Gyapong J, Mtei G (2012) Progress towards universal coverage: The health systems of Ghana, South Africa and Tanzania. Health Policy Plan 27: i4-i12.

- Hong R, Ayad M, Ngabo F (2011) Being insured improves safe delivery practices in Rwanda. JÂ Community Health 36: 779-784.

- Anderson R (1968) Behavioral model of families' use of health services. Center for health administration studies. University of Chicago, Chicago.

- Bashar S, Dahlblom K, Stenlund H (2012) Determinants of the use of skilled birth attendants at delivery by pregnant women in Bangladesh. Unpublished masters’ dissertation, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umea International School of Public Health, Umea University, Sweden.

Citation: Asiedu C (2019) Influence of Socio-Demographic Characteristics on Use of Skilled Delivery Services (SDS) at Health Facilities by Pregnant Women in the Central Region of Ghana. J Preg Child Health 6:403. DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000403

Copyright: © 2019 Asiedu C. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5586

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Oct 22, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4659

- PDF downloads: 927