Improving California’s Capacity to Implement a Positive Youth Development Intervention for Expectant and Parenting Adolescents

Received: 30-Jun-2018 / Accepted Date: 18-Jul-2018 / Published Date: 23-Jul-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000623

Keywords: Adolescent pregnancy; Evaluation program; Case management; Training programs; Resilience; Psychological

Introduction

Despite steady declines in births to adolescents, rates in the U.S. remain higher than all other industrialized nations and there are significant racial/ethnic disparities [1]. Adolescent parents face challenges that limit their choices and opportunities for success, including but not limited to, inadequate or unsafe living environments, racial and income inequalities, and insufficient access to health care and education. The risks associated with early childbearing are well documented. For instance, adolescent mothers are substantially less likely to complete high school or obtain a GED when compared to women who delay childbearing [2]. Compared to children born to older mothers, children of teenage mothers are also more likely to be premature or of low birth weight, placing these infants at greater risk of health problems [3,4]; they also tend to have higher incarceration rates and are more likely to become teen parents themselves. However, despite this increased risk, adverse outcomes are not inevitable. All adolescents have strengths and deserve opportunities to identify, build on, and enhance their capabilities, knowledge, skills, and assets in order to thrive. With appropriate support, expectant and parenting youth (EPY) and their offspring can achieve positive health, social, academic and economic outcomes [5-9].

Positive Youth Development (PYD) is an evidence-based strategy that has been shown to promote positive youth outcomes (e.g. increase self-sufficiency, responsibility, pro-social skills and civic participation) as well as protect youth from risky behaviors (such as tobacco and alcohol initiation and sexual risk among others) [10-12]. PYD, strength-based approaches that are tailored to adolescent parents’ unique needs, support EPY in pursuing healthy and successful futures for themselves, their families and future generations. As a result, the California Department of Public Health’s Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Program(MCAH) developed the Adolescent Family Life Program Positive Youth Development (AFLP PYD) model to align with the needs of expectant and parenting teens by providing case management support based on a positive youth development framework and with a specific focus on linkage to services; improving health and health care; increasing social and emotional support; and supporting the pursuit of education and employment. The AFLP PYD The AFLP PYD case management intervention is founded in a resilience framework, with nine guiding principles: strengths-based, youth voice and engagement, caring case manager-client relationship, supportive networks and community involvement, goal-oriented, empowerment and opportunity (setting high expectations), culturally responsive and inclusive, developmentally appropriate, and long-term and sustainable. The objectives of the AFLP PYD model are to: increase EPY’s access to and utilization of needed services; increase social and emotional support; build resiliency; increase educational attainment and employability; and improve pregnancy planning and spacing. AFLP PYD is voluntary and serves EPY under 19 years of age with a goal of twice-monthly case management visits including quarterly home visits.

Through a youth-centered, strengths-based and caring relationship, case managers guide youth through a series of activities and focused conversations to promote protective factors, which support youth in developing resilience strengths and skills including problem solving skills, sense of purpose, autonomy, and social competence. Case managers collaborative with youth through activities and processes that are grouped into four program phases: 1) Engagement, Initial Assessment and Plan Development; 2) Fostering Strengths & Sense of Purpose; 3) Empowerment & Implementation of Life Planning and Goal Pursuit; and 4) Transition and Program Exit.

Each phase consists of a series of core activities and focused conversations that are required to be completed within the face-to-face visits that case managers have with youth. In addition, at each visit, case managers check in with youth about the four program priority areas: family planning and safer sex; health and health care; education and work; healthy relationships. The activities can be accomplished in ways that are appropriate for individual case managers to meet the needs of youth.

MCAH developed the AFLP PYD program model with significant input from experts in the field, case managers, supervisors, and EPY (both English and Spanish-speakers). Between September 2013 and June 2014, MCAH contracted with the University of California, San Francisco to conduct a formative evaluation of AFLP PYD as it was being pilot tested at 10 sites throughout California. The formative evaluation informed program improvements and supported MCAH’s efforts to develop a standardized, evidence-informed case management intervention that was acceptable and feasible to implement.

Once the intervention was finalized, MCAH sought to improve the capacity of AFLP PYD agencies to implement the intervention with fidelity. They conducted a state-wide training for AFLP PYD case managers and supervisors across California. An independent evaluation team conducted a rigorous evaluation of the AFLP PYD training to assess the impact of the training on participants’ knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy and case management practice.

Methods

To assess the impact of the training on AFLP PYD participants’ knowledge and program practices, participants were asked to complete an on-line survey pre-post survey. The survey was administered to all training participants one month before attending the AFLP PYD training and again four months after completing the training. AFLP PYD staff were given two weeks to complete the survey. Daily e-mail reminders and telephone reminders were provided as needed to participants who had not yet completed the survey up until the survey close date. Knowledge about the AFLP-PYD model was assessed using three free-response items that asked participants to name up to three of the PYD principles, three protective factors and the four AFLP PYD program priorities. Each respondent was scored on the number of correct items listed for each question on the pre and post-test surveys. The survey also asked participants to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements to assess knowledge of AFLP PYD program concepts (10 items) and case management practice (11 items) using a 5-point Likert scale where 5=Strongly Agree and 1=Strongly Disagree. For Likert-response items, a response was scored as “correct” if a participant indicated that they agreed (“strongly” or “somewhat”) to an accurate statement or, conversely, “strongly disagree” or “somewhat disagree” to an incorrect statement. Neutral responses were classified as incorrect in both circumstances. In order to measure individual differences in knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy and management practices in AFLP staff, data was restricted to those participants who completed both, pre-training and post-training surveys.

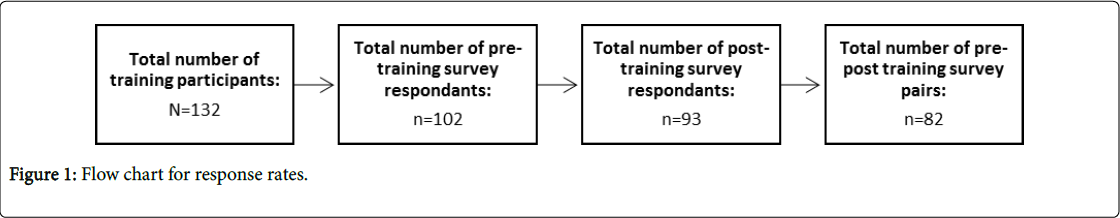

Figure 1 presents the flow chart for the response rate. The pre and post-training surveys were distributed to all of the 132 AFLP PYD staff scheduled to attend the training. Of these, 77% (n=102) responded to the pre-training survey and 70% (n=93) responded to the post-training survey. Power analyzes indicated that a sample size of 71 would be sufficient to detect a medium effect size (5) with an alpha of .05 and an SD of 1.5 [13]. There were a total of 82 complete pre-post training survey pairs which were used to analyze pre-post differences.

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and standard deviations) were used to analyze survey response rates, participants’ demographics, prior education, and work and training experiences. Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples was used to assess prepost differences between pre-test and post-test.

All survey data was collected online and analyzed with using SPSS version 23 [14], and STATA 15 [15]. The Wilcoxon test for paired samples is the non-parametric equivalent of the paired samples t-test and is used when sample data are not normally distributed [16].

A second goal of the training evaluation was to assess participants’ perceptions of the quality of the training and to identify aspects of the training that worked well and what, if any, areas needed to be improved. A brief, anonymous, paper-based survey was administered immediately following the training.

Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements about the quality of the training and its impact on improving their knowledge and self-efficacy in implementing the AFLP PYD intervention using the same 5-point Likert agreement scale and open-ended items to provide additional feedback about the training.

This study was approved by the UCSF and state institutional review boards.

Results

Table 1 presents the total survey respondents across all of the AFLP PYD sites by race or ethnicity, levels of education, roles at the AFLP agencies, and training history. AFLP PYD staff are racially/ethnically diverse. Over a half of the respondents (55%) identified as Latino or Hispanic. Approximately half (47%) had a bachelor degree and over a quarter (28%) had a post-graduate degree. Most of the participants were AFLP case managers (68%) and 32% were supervisors. Additionally, many of the training participants reported prior training related to PYD or motivational interviewing which were most commonly provided by local community organizations.

| Respondents | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Pre-training respondents | 102 (77.3%) |

| Post-training respondents | 93 (70.5%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 58 (54.7%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 19 (17.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American | 14 (13.2%) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 11 (10.4%) |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan | 1 (0.9%) |

| Another Race | 1 (0.9%) |

| Two or more races | 2 (1.9%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school or equivalent | 2 (1.9%) |

| Some college | 12 (11.3%) |

| Associate degree | 6 (5.7%) |

| Bachelor's degree | 50 (47.2%) |

| Post-graduate attendance | 6 (5.7%) |

| Post-graduate degree | 30 (28.3%) |

| AFLP Role | |

| Case Mangers | 73 (67.6%) |

| Supervisor | 35 (32.4%) |

| Participated in other related trainings prior to the AFLP PYD training | |

| Prior PYD-related training | 104 (78.8%) |

| Prior training on motivational interviewing | 104 (78.8%) |

Table 1: Participant demographics.

Pre-post improvements in participants’ knowledge about AFLP PYD

As noted previously, pre-post differences in knowledge, attitudes and case management practice were analyzed using the 82 paired respondents who completed both the pre and post-training survey. There were statistically significant pre-post improvements in all three of the free-response knowledge categories that asked participants to correctly name AFLP PYD concepts (Table 2).

| Knowledge Items | % of training participants who correctly answered statement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training Mean (SD) | Post-training Mean (SD) | Pre-Post Difference | |

| Correctly named at least one PYD principle | 43.21 (0.50) | 87.65 (0.33) | 44.44%** |

| Correctly named at least one youth resilience factor | 49.37 (0.50) | 89.87 (0.30) | 40.51%** |

| Correctly named at least one AFLP priority | 71.25 (0.46) | 90.00 (0.30) | 18.75%** |

| Youth in crisis should not be asked to set goals | 68.29 (0.47) | 69.51 (0.46) | 1.22% |

| Youth should take the lead in establishing goals for themselves | 72.84 (0.45) | 76.54 (0.43) | 3.70% |

| Values are something that are acted upon | 55.00 (0.50) | 63.75 (0.48) | 8.75% |

| Some youth are so vulnerable that I should not set high expectations for them | 69.51 (0.46) | 71.95 (0.45) | 2.44% |

| Values influence behaviors | 88.90 (0.78) | 92.60 (0.68) | 3.70%* |

| Helping youth participate in their community builds resilience | 91.36 (0.28) | 93.83 (0.24) | 2.47% |

| This is an excellent example of approaching cognitive dissonance. "You value exercise, but you haven't worked out in a month”. | 43.75 (0.50) | 61.25 (0.49) | 17.50%** |

| S.M.A.R.T. goals do not need a timeframe | 61.73 (0.49) | 85.19 (0.36) | 23.46%** |

| *p<.05; **p<.001 | |||

Table 2: Pre-post-training differences in AFLP PYD knowledge.

There were also significant improvements in participants’ knowledge of how values influence behaviors, goal setting and cognitive dissonance (Table 2).

Pre-post improvements in case management practices

Of the 11 items used to assess the impact of the training on case management practice, there were significant improvements on three items related to goals setting (assisting youth on developing, setting and achieving their goals) (Table 3). There were declines between pre and post-test for a few items, but these declines were not statistically significant.

| Case management practice | % of training participants who correctly answered statement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training Mean (SD) | Post-training Mean (SD) | Pre-Post Difference Mean (SD) | |

| I assist youth in reflecting on caring relationships in their lives | 93.90 (0.24) | 96.34 (0.19) | 2.44% |

| I assist youth in developing S.M.A.R.T. goals | 74.39 (0.44) | 92.68 (0.26) | 18.29%** |

| I know how to assist youth in reframing problems | 86.59 (0.34) | 84.15 (0.37) | -2.44% |

| I know how to include life planning into my visits | 90.24 (0.30) | 91.46 (0.28) | 1.22% |

| When youth are in crisis, it is up to me to determine the best course of action | 55.56 (0.50) | 59.26(0.49) | 3.70% |

| I use specific approaches to help youth identify their personal strengths | 81.48 (0.39) | 88.89 (0.32) | 7.41% |

| I establish high expectations for all youth | 53.66 (0.50) | 65.85 (0.48) | 12.20%** |

| I rarely provide time for youth to reflect on past successes to help them achieve their goals | 87.65 (0.33) | 88.89 (0.32) | 1.23%* |

| I encourage youth to have caring relationships | 95.00 (0.22) | 91.25 (0.28) | -3.75% |

| I assist youth in using their strengths to work on their goals | 100.00 (0.00) | 95.06 (0.22) | -4.94% |

| I assist youth in identifying opportunities to participate and contribute in ways that are important to them | 93.83 (0.24) | 87.65 (0.33) | -6.17% |

Table 3: Pre/post-training differences in case management practice.

Immediate post-training survey

In addition to the pre-post survey, all training participants were asked to complete an anonymous survey immediately following the training. A total of 222 participants completed this survey. Participants consistently and strongly agreed with statements that indicated the training improved their understanding of AFLP PYD (78%) and improved their ability to implement the intervention (81%). Most participants (97%) either strongly agreed or agreed that the training increased their self-efficacy (confidence in their ability) to use a PYD approach during all visits with youth, integrate motivational interviewing techniques to support youth in developing goals, and to make adaptations to the intervention without compromising its core components. Participants also rated the quality of the training high. Specifically, almost all participants (99%) reported that the content was clear and easy to understand and 96% reported they learned a great deal from the training. The peer support/learning was especially effective in improving their ability to implement PYD (96%) and most (90%) felt the role plays improved their ability to implement PYD (though a couple of participants suggested there should be fewer role plays).

Discussion

While Positive Youth Development (PYD) is an evidence-based strategy that has been found to protect youth from risky behaviors [10,11], to date it has not been studied in the context of case management practice to promote resilience and positive outcomes among EPY. A first and critical step to improve agency and staff capacity to implement PYD into a more standardized approach to case management practice is to provide staff with training on the theory/ evidence of the intervention framework and how to integrate this evidence-based approach into practice. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the extent to which a PYD training can enhance case manager’s capacity to integrate PYD practices.

There are several limitations to this study. The survey used to assess the training was developed specifically for this evaluation and it is not a validated instrument. It was not possible to include a comparison group which is necessary to assess if the pre-post improvements would have occurred regardless of the training. Further, it was not able to compare non-survey respondents with survey respondents because staff-level data was only available from those who completed the survey. The training evaluation data was self-reported and is not necessarily a true reflection of actual changes to case management practice. In addition, due to the small sample size, it was not possible to assess other factors that could influence the findings. In particular, raining evaluation data was self-reported and is not necessarily a true reflection of actual changes to case management practice either prior to or after the AFLP PYD training.

In addition, it was not possible to control for prior training and it is important to note that over ¾ of training participants reported receiving some prior training on topics covered in the state AFLP PYD training. However, even with prior training, the State AFLP PYD training demonstrated significant increases in d knowledge and improved aspects of case management practice.

Conclusion

This independent evaluation of MCAH’s AFLP PYD training found that the training significantly improved participants’ knowledge, attitudes and self-reported ability to implement the AFLP PYD intervention. In particular, there were significant improvements in participants’ knowledge of PYD principles, protective factors and AFLP PYD priorities between pre and post-test training surveys. The training was well-received and almost all of the participants felt that the training improved their ability to use a PYD approach during all visits with youth; helped them to integrate motivational interviewing techniques to support youth in developing goals, and to make adaptations to the intervention without compromising its core components.

The AFLP PYD program was selected to participate in a federal evaluation that is using a randomized control trial to examine the impact of this intervention on improving a number of outcomes for expectant and parenting adolescents over time.

References

- Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, Eilers MA, Singh S (2015) Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: Levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health 56: 223-230.

- Addo FR, Sassler S, Williams K (2016) Reexamining the association of maternal age and marital status at first birth with youth educational attainment. J Marriage Fam 78: 1252-1268.

- Khashan AS, Baker PN, Kenny LC (2010) Preterm birth and reduced birthweight in first and second teenage pregnancies: A register-based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10: 36.

- Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Morisaki N, Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, et al. (2014) WHO multicountry survey on maternal newborn health research network. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: A World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG 121: 40-48.

- Lerner RM, Lerner JV (2009) Report of the findings from the first six years of the 4-H study of positive youth development.

- Redd Z, Cochran S, Hair E, Moore K (2002) Academic achievement programs and youth development: A synthesis.

- Thorland W, Currie DW (2017) Status of birth outcomes in clients of the nurse-family partnership. Matern Child Health J 21: 995-1001.

- House LD, Bates J, Markham CM, Lesesne C (2010) Competence as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth: A systematic review. J Adolesc Health 46: S7-S22.

- Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM, Peskin MF, Flores B, et al. (2010) Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. J Adolesc Health 46: S23-S41.

- Miller TR (2015) Projected outcomes of nurse-family partnership home visitation during 1996–2013, USA. Prev Sci 16: 765-777.

- Asheer S, Burkander P, Deke J, Worthington J, Zief S (2017) Raising the bar: Impacts and implementation of the new heights program for expectant and parenting teens in Washington, DC. OAH Evaluation Report.

- Ryan CA, Hoover JH (2005) Resiliency: What we have learned. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 14: 117.

- Clinical & Translation Science Institute (1995) Sample size calculators. Sample size calculators for designing clinical research.

- IBM Corp (2015) IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- StataCorp (2017) Stata statistical software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Conover WJ (1999) Practical nonparametric statistics, (3rd edn). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Citation: Tebb K, Rodriguez F, Price M, Rodriguez F, Brindis C (2018) Improving California’s Capacity to Implement a Positive Youth Development Intervention for Expectant and Parenting Adolescents. J ommunity Med Health Educ 8: 623. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000623

Copyright: © 2018 Tebb K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3403

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Apr 04, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2615

- PDF downloads: 788