Implementation of Postpartum Depression Screening and Referral

Received: 03-May-2023 / Manuscript No. JCPHN-23-97825 / Editor assigned: 05-May-2023 / PreQC No. JCPHN-23-97825 (PQ) / Reviewed: 19-May-2023 / QC No. JCPHN-23-97825 / Revised: 22-May-2023 / Manuscript No. JCPHN-23-97825 (R) / Published Date: 29-May-2023 DOI: 10.4172/2471-9846.1000417

Abstract

Women in the United States most at risk for postpartum depression (PPD) are disproportionately impoverished racial/ethnic minorities. The prevalence of PPD increases from affecting 1 in 8 mothers in the nation compared to 1 in 3 mothers in low-income communities. Women from low-income neighbourhoods tend to face barriers to quality mental healthcare due to socio-economic challenges. At a home visiting clinic in Baltimore City, there have been lower numbers of positive depression screenings (9%) than referrals for mental health services for PPD (31.7%) (Showing a discrepancy between screening and referring for PPD). Given the vast effects of PPD clinicians should formulate a plan to decrease the rate of untreated PPD. This plan should include consistent screening for PPD until at least 12 months postpartum.

This quality improvement project was aimed to implement an evidence-based screening and referral process for PPD for women from low-income areas using the Patient Health Questionnaires (PHQ) 2 and 9.

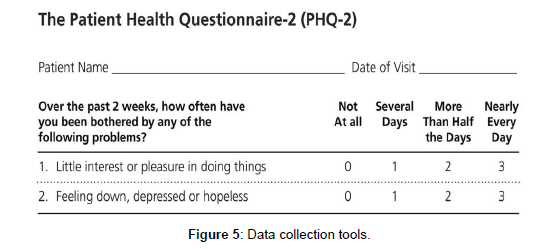

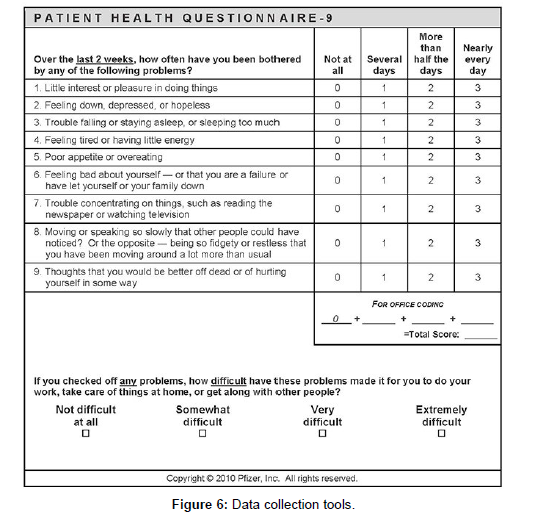

This project occurred at a home visiting clinic over 14 weeks. Women ages 17-44 in a low-income area identified by U.S. census data. Staff education was conducted with the community health workers (CHW) on PPD and administering and scoring the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9. Women who were positively screened for PPD using the PHQ-2 (a score of two or more) were then screened with the PHQ-9. If the score of the PHQ-9 was four or higher (indicating mild depression), the woman received a direct referral for mental health services. Project data was collected on the data management spreadsheet using medical records audits. A run chart of the data was completed to identify trends.

100% of staff educated (18 staff members) before implementation. Fourteen percent (n=23) of clients screened positive for PPD. An increase of 64% compared to preimplantation rates. 100% of clients with a positive score had a referral for mental health services.

Results from this QI project demonstrated that routine depression screening of postpartum women can facilitate timely referral for mental health services. In the future, considering the target populations social determinants of health when administering postpartum depression screenings as well as staff education, training and check-ins may benefit similar clinics.

Keywords

Postpartum depression; Maternal mental health; PHQ-9; PHQ-2; Maternal health disparity

Introduction

Practitioners must consider the target population and social determinants of health when administering postpartum depression screenings and use tools with high sensitivity in that population. Women in the United States most at risk for postpartum depression (PPD) are disproportionately impoverished racial/ethnic minorities. The prevalence of PPD increases from affecting 1 in 8 mothers in the nation compared to 1 in 3 mothers in low-income communities. Edinburgh postnatal depression scale is the most widely used screening tool for women of depression.

Given the vast effects of PPD on the entire family and the disproportionate distribution of PPD among women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, clinicians should devise a plan to decrease the rate of untreated PPD. Having an appropriate sensitive screening tool for this population is vital in this effort and the Edinburgh scale has not been studied in this specific population. The QI project helps identify other screening tools you can use in the specified population.

Methodology

Postpartum Depression (PPD) can adversely affect the mental and emotional well-being of the mother and, in severe conditions, may lead that mother to harm herself or her child. (American Psychological Association [1]. It can also lead to issues in child development and infant and mother attachment [1, 2, and 3]. Studies show that the populations in the United States most at risk for PPD are disproportionately impoverished racial/ethnic minorities. The prevalence of PPD increases from affecting 1 in 8 mothers in the nation to affecting 1 in 3 mothers in low-income communities [2, 3, and 4]. Unfortunately, women from low-income neighborhoods tend to face barriers to accessing quality mental healthcare due to the lack of financial resources and socioeconomic challenges [5, 6, and 7]. Given the vast effects of PPD on the entire family and the disproportionate distribution of PPD among women from lower socio-economic backgrounds, clinicians should devise a plan to decrease the rate of untreated PPD.

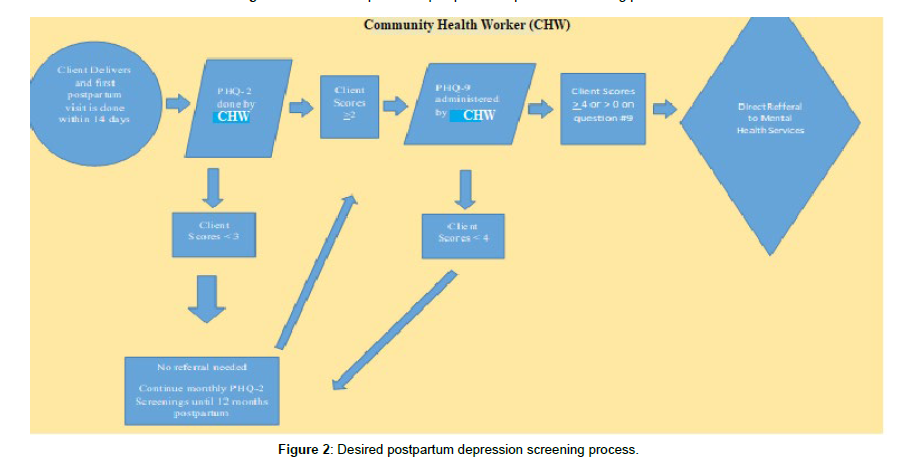

A needs assessment was completed in the summer and fall of 2020 at a home visiting clinic in Baltimore city. Between July 1st, 2020, and September 30th, 2020, there were 189 postpartum clients. 20 of 189 were in their first month postpartum and had an Edinburgh postnatal depression scale administered, finding three of 20 were positive. Seven of 189 clients had a positive PHQ-2. Looking at referrals, there were 26 mental health referrals for postpartum depression. Reviewing these numbers, a gap was noted between the number of clients who screened positive and the number of postpartum depression referrals. At the practice site, women are currently screened with the PHQ-2 and are given referrals to mental health services as needed. The previous flow process can be seen in (Figure 1). This process is not was not being monitored, and many women were not being screened for PPD. Referrals were placed when a CHW believed there may be a need for one. This led to low numbers of screenings being done and possibly led to missed cases of PPD. This quality improvement project aimed to implement an evidence-based screening and referral process for postpartum depression for women from low-income areas. This was done using the PHQ-2 followed by a PHQ-9, if positive, monthly until 12 months postpartum. The goal was to increase PPD screening to 100% of all clients contacted and have 100% of postpartum women enrolled in the program who were positively screened for postpartum depression have a direct referral for mental health services (Figure 2).

Evidence Review

A review and synthesis of the evidence were completed to support the practice change. The evidence review table can be seen in (Table 1).

| O'Connor, E., Rossom. R.C., Henninger, M., Groom, H.C., Burda, B.U. (2015). Primary Care Screening for and Treatment of Depression in Pregnant and Postpartum Women: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(4):388–406. doi:10.1001/JAMA.2015.18948 | Level I | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose/ Hypothesis |

Design | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

| "To systematically review the benefits and harms of depression screening and treatment, and accuracy of selected screening instruments, for pregnant and postpartum women." | Systematic Review | Search Strategy: MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Collaboration Registry of Controlled Trials Eligible studies: Studies between 2008 and 2015. English language fair- and good-quality studies involving women who were 18 years and older and pregnant or postpartum (within one year of birth at enrollment) and living in "very high-developed" countries, according to the World Health Organization |

Control: Controls varied between studies included in the S.R. Intervention: Interventions in the studies in the S.R. were Protocol: Not applicable to S.R. critique | Dependent Variable: Researchers chose articles based on the objective question (K.Q.s) to which they were referring.

Benefits and harms of depression screening (KQ1, KQ3)

Diagnostic Accuracy of PHQ and Edinburgh Postnatal screening tool (KQ2) benefits of antidepressants and behavioral-based treatments (KQ4) harms of treatment (KQ5) |

Level of measurement: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)18 for observational studies and A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) for systematic reviews were used. Outcome Data Retrieval: Researchers: pooled data from all articles and categorized them based on the objective question. Analysis: All significance testing was 2-sided, and results were considered statistically significant if the P-value was .05 or less. The specificity of the EPDS was 0.87 or greater in all studies. Sensitivity for major and minor depression, using the cut-off of 10 or greater, ranged from 0.63 (95% CI, 0.44-0.79) to 0.84. At a cut-off score of 10, the study of low-income African American women reported a sensitivity of 0.84 (95% CI, 0.69-0.94) and specificity of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.70-0.89) for identifying major or minor depression in pregnant and postpartum women combined. Sensitivities and specificities were wide-ranging for Patient health questionnaires Conclusion: Screening instruments can identify pregnant and postpartum women who need further evaluation need treatment for depression. Screening can reduce the prevalence of depression in a population. The EPDS is a validated tool for screening for depression. The PHQ-2 should be followed by a PHQ-9 and is recommended in practice guidelines. |

| De Albuquerque Moraes, G. P., Lorenzo, L., Pontes, G. A. R., Montenegro, M. C., & Cantilino, A. (2017). Screening and diagnosing postpartum depression: when and how? Trends in Psychiatry & Psychotherapy, 39(1), 54–61. https://doi-org.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0034 | Level I | ||||

| Purpose/ Hypothesis |

Design | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

| "To review which instruments have been used over recent years to screen and diagnose PPD and the prevailing periods of diagnosis." | Systematic Review | Search Strategy: Searches were run on three databases, MEDLINE, SciELO, and LILACS, using the clinical terms postpartum depression, postnatal depression, perinatal depression, and puerperal depression in publication titles, plus one of the diagnostic terms screening, diagnosis, diagnostic, evaluation, interview, questionnaire, scale, score, cut-off, or time, in either title or abstract

Eligible studies: were original articles published in English in the past five years describing studies of female humans and containing at least one of the terms referring to instruments used in screening, diagnosis, evaluation, or time for assessment of PPD, in the title or abstract. Exclusion criteria: if they were not original, were review papers (except for meta-analyses), or were case reports. |

Control: Controls varied between studies included in the SR. each article was classified according to 6 categories: risk factors and etiology; prevalence; screening and diagnostic instrument validation; prevention and treatment; and consequences Intervention: Interventions in the S.R. studies were only items related to screening and diagnosing postpartum depression. Protocol: Not applicable to S.R. critique | Dependent Variable: screening and diagnosis of postpartum depression using any commonly used tools. Measure: It was Calculated the frequency each tool was used in studies. Calculations were made about the time since birth PPD was detected. | Level of measurement: Chi-square analyses were used to compare the AUCs of the EPDS and PHQ-9. Statistical Contrasts between the EPDS and PHQ-9 diagnostic algorithms were performed using the Fisher Exact test. EBPDS was used in 68% of the sample (15 articles), followed by the BDI-II (27%, six articles), the PHQ-9 (18%, four articles), and the CES-D (9%, 1 article). Conclusion: The risk of postpartum depression extends past six weeks up to one year, and it is essential to develop a screening strategy that expands through this period. EPDS is the most commonly used tool, Followed by the PHQ-9. |

| Flynn HA, Sexton M, Ratliff S, Porter K, Sivin K. (2010). Comparative performance of the Edinburgh postnatal scale and the patient health questionnaire-9 in pregnant and postpartum women seeking psychiatric services. Psychiatry Reserves. 187(1–2):130–4.10.1016/j.psychres.2010.10.022 | Level: III | ||||

| Purpose/ Hypothesis |

Design | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

| "Adoption of a standard depression measures across clinics and populations is advantageous for continuity of care and facilitation of research. This study provides information on the comparative utility of a commonly used perinatal-specific depression instrument (the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale—EPDS) with a general depression screener (Patient Health Questionnaire-9—PHQ-9) in a sample of perinatal women seeking psychiatry services within a large health care system." |

Prospective Controlled Trial | Sampling Technique: Convenience

Inclusion: pregnant or postpartum and seeking care at the clinic during the study time frame Exclusion: unclear diagnosis or remission status (n=29), present or likely bipolar disorder (n=29), mixed or atypical, not otherwise specified (NOS) depression diagnoses (n=10), or incomplete data (n=9) # Eligible: 251 # Accepted:185 # Intervention: 58 Group Homogeneity: Intervention/Control homogeneous based on N.S. p values in Table 1 |

Control: Clinician diagnosed MDD, NDD Intervention: PHQ-9 and EPDS to diagnose MDD | Dependent Variable: Edinburgh and PHQ-9 result in detecting MDD and ruling out NDD.

Measure: Relationships between the EPDS and PHQ-9 results were measured using Pearson correlations. Internal reliability was assessed with Cronbach's alpha. |

Statistical Results: Chi-square contrast analysis did not detect a significant performance difference (χ2=0.36, p=0.55) between the two measures (PHQ-9 and Edinburgh) PHQ-9 and EDPS are equally effective in detecting MDD in perinatal and postpartum women. |

| Merz, E. L., Malcarne, V. L., Roesch, S. C., Riley, N., & Sadler, G. R. (2011). A multigroup confirmatory factor analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 among English- and Spanish-speaking Latinas. Cultural diversity & ethnic minority psychology, 17(3), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023883 | Level IV | ||||

| Purpose/ Hypothesis |

Design | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

| "In this study, we investigated the reliability and structural validity of the PHQ-9 in Hispanic American women." | Cross-Sectional Community based study | Sampling Technique: Convenience Inclusion: English Speaking or Spanish speaking self-identifying as Hispanic Exclusion: not listed # Accepted:479 # Interventions: English-speaking = 245, Spanish-speaking = 234 Power analysis: Not indicated Group Homogeneity: homogeneous based on N.S. p values in Table 1 for characteristics |

Control: none Intervention: PHQ-9 was given to women in their perspective languages. | Dependent Variable: PHQ-9 Scoring results Measure: Scores of the PHQ-9 test with a score Greater than equal to 10 indicate the respondent may be depressed. | Statistical Results: Mean PHQ-9 scores were not significantly different between groups, t (477) = −.356, p > .05. Cronbach's alphas were calculated for the English and Spanish groups. In the current sample, the internal consistency was good for English (α = .84) and Spanish (α = .85) versions. Conclusion: PHQ-9 has good internal consistency and structural validity. Therefore, it is recommended as an appropriate measure of depression screening in Latinas. |

| Hansotte, E., Payne, S. I., & Babich, S. M. (2017). Positive postpartum depression screening practices and subsequent mental health treatment for low-income women in Western countries: a systematic literature review. Public Health Reviews (2107-6952), 38(1), 1–17. https://doi-org.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/10.1186/s40985-017-0050-y | Level V | ||||

| Purpose/ Hypothesis |

Design | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

| "The objective of this systematic literature review is to compile factors that hinder and improve access to postpartum depression treatment in low-income women after a positive screen for postpartum depression. The key The question of focus is: what are the characteristics associated with access to mental health treatment for low-income women with a positive postpartum depression screen in Western countries?" |

Systematic Review | Search Strategy: A PRISMA-based systematic literature review was conducted. PubMed and EBSCO databases were searched Eligible studies: Studies published in English before February 2016 that looked at treatment for postpartum depression in low-income women who had been identified with the condition. Inclusion: empirical, English-language, peer-reviewed publications were considered for this study. Exclusion: reviews (including analyses), case reports, letters to the editor, executive summaries, governmental reports, and commentaries. articles that did not include treatment as an outcome, articles that did not look at low-income women specifically, incomplete studies, articles that did not have a postpartum women group, and those for which treatment as an outcome was theoretical rather than measured |

Control: Controls varied between studies included in the S.R. Intervention: Interventions in the studies in the S.R. were Protocol: Not applicable to S.R. critique | Dependent Variable: Barriers to women having access to care after a positive screen for PPD. Measure: Qualitative reports of barriers | Level of Measurement: Qualitative analysis technique of constant comparative analysis, data extracted from included articles were inductively coded by treatment characteristics and barriers. Outcome Data Retrieval: Researchers: pooled data from all articles Data analysis: Patterns and themes that were developed from the coded data and two major topics are characteristics of PPD treatment and barriers to mental health treatment Conclusion: Financial barriers, stigma, not being familiar with PPD, and negative experiences with mental health professionals kept women from low-income backgrounds seeking care after a positive result. It is essential to use all resources to mitigate these barriers. Home health visitors to help screen and treat clients are effective in this population. |

Table 1:Evidence review table.

Level of Evidence Type of Evidence

I (1) Evidence from systematic review, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or practice- guidelines based on systematic review of RCTs.

II (2) Evidence obtained from well-designed RCT and/or reports of expert committees.

III (3) Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization.

IV (4) Evidence from well-designed case-control and cohort studies

V (5) Evidence from systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative study

VI (6) Evidence from a single descriptive or qualitative study

VII (7) Evidence from the opinion of authorities

The evidence synthesis table can be seen in (Figure 3). Although the majority of sources recommend the routine screening of postpartum women for PPD, De Albuquerque concluded the risk of postpartum depression extends past six weeks up to one year; therefore, it is essential to develop a screening strategy that expands through this period [4]. This coincided with The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommended screening for postpartum depression for up to 12 months after delivery. Therefore, the recommendation for the practice change is that screening is done monthly until 12 months postpartum.

Screening can be done using many depressions screening tools, including the patient health questionnaires [5]. O’Connor noted that screening instruments could identify pregnant and postpartum women who need further evaluation and need treatment for depression, screening can reduce the prevalence of depression in a population, and that the PHQ-2, if positive, should be followed by a PHQ-9. This is

recommended in practice guidelines. Flynn validated that the PHQ-9 and Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) are equally effective in detecting MDD in perinatal and postpartum women [6].

Given that the target population of this practice change is lowincome black and Hispanic women, further research was conducted to ensure the population characteristics were considered. Hansotte, Payne & Babich found that financial barriers, stigma, not being familiar with PPD, and negative experiences with mental health professionals kept women from low-income backgrounds from seeking care after a positive result. Therefore, it is essential to use all resources to mitigate these barriers. Home health visitors can help screen and treat clients effectively in this population [s]. found that the PHQ-9 screening tool has good internal consistency and structural validity and is recommended for screening for depression in Latina women. Despite a possible language barrier using the patient health questionnaire translated into Spanish with this target population can be effective. Four studies concluded that the PHQ is an appropriate tool for black and Hispanic postpartum women to identify postpartum depression.

Theoretical Framework

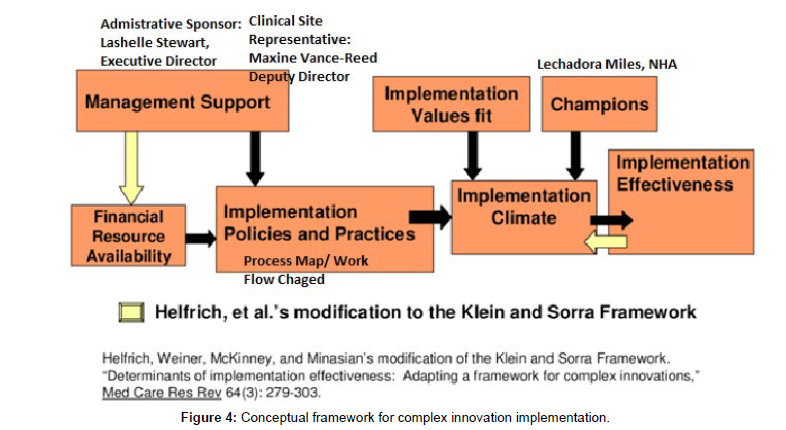

The practice theory used for this project was Meleis' Transitions Theory (Figure 4). The goal of the transition theory is to help people go through healthy transitions to enhance healthy outcomes [9]. This theory can be applied to childbirth and the development (or not) of postpartum depression. The theory notes that the transition experience occurs before the event and has a fluid ending point, indicating why mothers should be monitored for depression before, during, and after delivery. In addition, this theory identifies 'change triggers,' and childbirth can be a developmental or situational trigger. Properties of the transition regarding postpartum depression can include disconnectedness and a lack of awareness. These properties can predispose the mother to postpartum depression. 'Conditions of the change' include community, societal and personal factors. Conditions such as low social-economic level decreased access to care, and increased risk factors for postpartum depression can affect the mother and put her at risk for postpartum depression. In the transitions theory, interventions facilitate and inspire healthy processes and outcomes. This can be done with an intervention that mobilizes support and provides resources, which will lead to patterns of response to receiving help and improved emotional wellbeing. The Complex Innovation Implementation Framework was used to guide this evidence-based practice change. Incorporating this theory into this practice change, management support was garnered and can be seen in the implementation team that included several of the organization's management team members [10]. The strategies and tactics used in this implementation plan incorporated key determinates, including champions and implementing policies and practices at the organization to help ensure implementation effectiveness. Practices and procedures were also re-designed for this implementation plan.

The organization that implemented this change caters to women in underserved areas in Baltimore City. The Census Bureau and Baltimore City have identified women in these areas as living in an area that needs additional resources. Many of these women were on Medicaid or did not have any health insurance. They also offer services to undocumented immigrants that have issues with access to healthcare. Therefore, the effect of this evidence-based practice change was geared toward reaching the most vulnerable populations. These women received these services free of charge. There were two Nurses, three case managers, and 12 Community Health Workers (CHW) that served 272 postpartum women in the organization (Figure 5).

The evidence-based intervention being changed focused on the postpartum depression screening and referrals process. The CHW performed monthly visits on every postpartum client. During their visit, the CHW completed a PHQ-2 questionnaire. This questionnaire was to be completed every month until 12 months postpartum. If positive, with a score of two or more, a PHQ-9 was completed. If scored a four or above on the PHQ-9, indicating mild depression, the CHW then provided the mother with a direct referral for mental health services. In this process, the nurse reviewed all referrals and questionnaires, and the case manager kept track that if a client had a positive screening, she had received a mental health referral using the data management spreadsheet and disposition log.

Structure measures included staff being trained on the new process map for postpartum depression and referral. During the educational meeting, demonstrations were given on conducting the interview, filling out the PHQ, and putting in a referral. Feedback from staff indicated that the demonstrations were the most helpful part of the training.

The goal was to have 100% of all eligible women screened for postpartum depression until 12 months postpartum. Tactics to help the process measure included audits on Tuesdays after meeting with the data expert. Once the data was evaluated, individual feedback was given to staff on the specific data they turned in. Another goal was to have 100% of all positive screening tools to have a mental health referral. Chart audits were conducted to help achieve this goal as well.

Data collection was conducted weekly via chart audits and data was entered into the data management system for evaluation. Data reports were run on the numbers each week on all clients who have completed screening. A manual review of mental health referrals was conducted weekly for each positive PHQ for postpartum depression. To protect patient privacy, no directly identifiable data were collected, and each client was given a number. This is a non-human subject quality improvement project therefore, IRB approval was not indicated (Figure 6).

Results

Before implementation, the structure measures of 100% of staff being trained on the new process map for postpartum depression and referral process to mental health services were completed by 18 staff members (three case managers, two nurses, and 13 CHWs were trained). The trend on the run chart showed low screening numbers in the first few weeks of implementation therefore, staff check-ins and re-education were completed in weeks 6, 9, and 13. This resulted in increased screening tools being completed in the subsequent weeks.

At the end of the 14 weeks of implementation, 134 PHQ screening tools were completed for PPD. There were 179 postpartum women enrolled in the program, but only 171 were able to be contacted during the implementation period. Women not contacted were excluded from the results. Fourteen percent (n=24) of postpartum women screened positive for PPD (score of 4 or more). This is a 64% increase in positive PPD screening tools compared to pre-implementation rates. The run chart trends showed increased screening rates every week after completed staff check-ins. During the week of thanksgiving, no screening tools were documented due to the office being closed for three days that week.

The process measure was to have 100% of all eligible women screened for postpartum depression until 12 months postpartum. During implementation, 74.8% of women were screened for PPD using the PHQs. Some identified barriers to reaching this goal included the high turnover of clients, a turnover of one case manager and two CHWs, which increased workloads, the inability to reach clients due to their change in phone numbers and housing, and disconnected phone lines (Table 2).

| Evidence-Based Practice Question (PICO): In low-income diverse women from urban settings, is screening and referring for postpartum depression using the patient health questionnaire and a referral system that helps eliminate barriers to seeking care, compared to no screening protocol, lead to a decrease in the prevalence of postpartum depression in this population. | |||

| Level of Evidence | # of Studies | Summary of Findings | Overall Quality |

| I | 2 | De Albuquerque Moraes et al. (2015) concluded that the risk of postpartum depression extends past six weeks up to one year. Therefore, it is essential to develop a screening strategy that expands through this period. It also noted EPDS is the most commonly used tool, followed by the PHQ-9. | B, this systematic review was well defined and had a reproducible search strategy. There was a conclusion on the frequency of screening but a general statement on the frequency of tools used. |

| O'Connor et al. (2017) noted that screening instruments could identify pregnant and postpartum women who need further evaluation need treatment for depression. Thus, screening can reduce the prevalence of depression in a population. The EPDS is a validated tool for screening for depression. The PHQ-2 should be followed by a PHQ-9 and is recommended in practice guidelines. | |||

| A This high-quality systematic review on practice guidelines was well defined with a significant number of studies. It provided definitive conclusions associated with the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended screening of adults for depression. | |||

| III | 1 | Flynn et al. (2010) validated that the PHQ-9 and EDPS are equally effective in detecting MDD in perinatal and postpartum women. | B, this study was controlled with sufficient sample size and a definitive conclusion on screening tools in postpartum women. |

| IV | 1 | Merz et al. (2011) found that the PHQ-9 screening tool has good internal consistency and structural validity and is recommended for screening for depression in Latina women. | B, no control group was indicated. The was a sufficient sample size, it was well designed, and strengths and limitations were shown. Thus, there was a fairly definitive conclusion. |

| V | 1 | Hansotte, Payne, & Babich (2017), Found that Financial barriers, stigma, not being familiar with what PPD is, and having a negative experience with mental health professionals kept women from low-income backgrounds seeking care after a positive result. It is essential to use all resources to mitigate these barriers. Home health visitors to help screen and treat clients are effective in this population. | B, this systematic qualitative review conducted a thorough search of well-defined studies. It noted the limitations and had definitive conclusions and recommendations |

Table 2:Synthesis table.

I (1) Evidence from systematic review, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or practice-guidelines based on systematic review of RCTs.

II (2) Evidence obtained from well-designed RCT and/or reports of expert committees.

III (3) Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization.

IV (4) Evidence from well-designed case-control and cohort studies

V (5) Evidence from systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative study

VI (6) Evidence from a single descriptive or qualitative study

VII (7) Evidence from the opinion of authorities

The long-term process measure was to have 100% of women screened positive for postpartum depression to have a direct mental

health referral for services. All 24 women who screened positive had a direct referral, meaning a mental health facility accepted the referral and was in the process of scheduling the intake and first visit. The process in which referrals were to be completed was changed before implementation due to the online platform UniteUs not being functional. Therefore, we created a working relationship with a nearby mental health facility with an electronic referral system. They worked closely with us to ensure all referrals were received and processed. Unfortunately, by the time implementation was complete, we could not assess the disposition of every woman to see if their mental health visit was completed.

Discussion

This quality improvement project's key impact was increased compliance and screening rates for postpartum depression in lowincome women. It was identified that the PHQ was more appropriate in this population. In addition, clients and staff commented PHQ tool was utilized more efficiently than the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Therefore, more patients were able to complete it without difficulty. This coincides with the research that identified internal consistency, validity, and better usability of the PHQ with women from lowincome backgrounds with decreased reading levels and in the Hispanic population.

In this population of low-income women in an urban city, PPD rates are expected to be 1 in 3 or 33%. In this quality improvement project, 14% of women screened positive for PPD. Some limitations were identified in the results and included being unable to reach clients due to their change in phone numbers and disconnected phone lines.

These limitations were increased since COVID-19 because CHWs were no longer primarily conducting in-person home visits; instead, all questionnaires were completed via phone. To adjust for this, we did not count women who could not be contacted at all during the implementation periods. Still, inconsistent communication could have been a barrier and affected results.

Conclusion

Women from low-income neighborhoods tend to face barriers to accessing quality mental healthcare due to the lack of financial resources and socio-economic challenges [11,12]. Given the vast effects of PPD on the entire family and the disproportionate distribution of PPD among women from lower socio-economic backgrounds, clinicians should devise a plan to decrease the rate of untreated PPD. This QI project demonstrated that routine depression screening of postpartum women with the PHQ could facilitate timely referral of mental health services. Healthcare providers must also consider the population they serve and their Social Determinants of Health when administering screening tools and implement using tools that are best suited for their patients. Identifying and referring women from high-risk populations for PPD treatment can help decrease the effects PPD has on the mother and family alike. It was determined from this QI project that in the future, continued support of the program with staff education, training, and check-ins may be beneficial to similar clinics. For sustainability at this clinic, case managers have been trained and added to their process to include in their monthly check-in with their CHWs that they are completing PPD screening tools and answering and providing support. Staff education will be conducted yearly and continued access to recorded training videos for new staff or a refresher for current staff.

References

- https://www.apa.org/topics/women-girls/postpartum-depression

- Badr L K, Ayvazian, N, Lameh S (2018) is the effect of postpartum depression on mother-infant bonding universal? Infant Behavior & Development 51: 15-23.

- Bauman,, Ko J, Cox S (2020) Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression — United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69: 575-581.

- De Albuquerque Moraes G P, Lorenzo L, Pontes GA R (2017) Screening and diagnosing postpartum depression: when and how? Trends in Psychiatry & Psychotherapy 39: 54-61.

- Flynn HA, Sexton M, Ratliff S, Porter K, Sivin K(2010) Comparative performance of the Edinburgh postnatal scale and the patient health questionnaire-9 in pregnant and postpartum women seeking psychiatric services. Psychiatry Reserves 187: 130-134.

- Hansotte E, Payne S I, , Babich S M (2017) Positive postpartum depression screening practices and subsequent mental health treatment for low-income women in Western countries: a systematic literature review. Public Health Reviews 38: 1-17.

- Helfrich CD, Weiner BJ, McKinney MM (2007) Determinants of implementation effectiveness adapting a framework for complex innovations. Medical Care Research and Review 64: 279-303.

- Meleis A I (2015) Transitions theory. Nursing theories and nursing practice 361-380.

- Meleis A I (2010) Transitions theory: Middle-range and situation-specific theories in nursing research and practice. New York NY: Springer.

- Merz E L, Malcarne VL (2011) A multigroup confirmatory factor analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 among English- and Spanish-speaking Latinas. Cultural diversity & ethnic minority psychology 17: 309-316.

- O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M (2015) Primary Care Screening for and Treatment of Depression in Pregnant and Postpartum Women: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016 315: 388-406.

- https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/11/screening-for-perinatal-depression

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Berchie-Gialamas M (2023) Implementation of Postpartum DepressionScreening and Referral. J Comm Pub Health Nursing, 9: 417. DOI: 10.4172/2471-9846.1000417

Copyright: © 2023 Berchie-Gialamas M. This is an open-access article distributedunder the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permitsunrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided theoriginal author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1440

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Mar 12, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1327

- PDF downloads: 113