Short Communication Open Access

Impact of National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) on Psychiatric Risk Assessment in Hospital Emergency Departments: Commentary on Research Study

1Eastern Health Psychiatric and Emergency Department Response Team, Victoria, Australia

2PhD Candidate, Monash University, Caulfield, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- E-mail: llj2920@163.com

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

Hospital Emergency Departments (EDs) continue to experience increased presentation rates (Maumill, et al. 2013). To address this high level of need, National Emergency Access targets (NEAT) have been introduced across the world to increase throughput of patients and prevent ‘access block’ (waiting more than eight hours for treatment) (Chang, et al. 2010). As the demand for ED treatment has increased, so too has there been an increase in mental health-related presentations, and at a faster rate than other patients (Slade, et al. 2010). These presentation are more complex, require more resources and are time consuming in nature (Zun, 2012), but are still required to be seen within NEAT timeframes. This has the potential to impact clinical practice by ED mental health workers as they have less time with more patients to assess and treat.

Introduction

Hospital Emergency Departments (EDs) continue to experience increased presentation rates (Maumill, et al. 2013). To address this high level of need, National Emergency Access targets (NEAT) have been introduced across the world to increase throughput of patients and prevent ‘access block’ (waiting more than eight hours for treatment) (Chang, et al. 2010). As the demand for ED treatment has increased, so too has there been an increase in mental health-related presentations, and at a faster rate than other patients (Slade, et al. 2010). These presentation are more complex, require more resources and are time consuming in nature (Zun, 2012), but are still required to be seen within NEAT timeframes. This has the potential to impact clinical practice by ED mental health workers as they have less time with more patients to assess and treat.

Aims and Methods

The aim of this study is to examine ED mental health clinician experiences of risk assessment for mental health patients since the implementation of NEAT. The study asks specifically, what effect has NEAT had on psychiatric assessment in Emergency Departments?

This study employed a mixed methods approach so it could utilise both the strengths of qualitative and quantitative information to increase the understanding of the research (Johnson, et al. 2007). The questionnaire covered a range of topics

A total of 78 participants across seven Metropolitan and surrounds EDs in Melbourne, Australia participated in the study. Ethics was approved across all Hospital networks and Monash University.

The Study Findings

Most respondents were ambivalent about NEAT as a concept, felt NEAT made their job considerable busier, and they received undue pressure the organisation to meet NEAT.

Participants noted there were positive aspects to NEAT. For example, patients waited less time to be seen, they were less likely to abscond, ED teamwork improved, clinicians could work more effectively, with unnecessary paperwork and assessment procedures becoming better streamlined. “Having to wait hours in the ED to be seen, particularly if mentally unwell, I can only imagine being awful” (respondent number 12).

Participants also noted there were negative features of NEAT. The focus on time was inappropriate, NEAT did not allow appropriate training of students, time with family and carers became reduced, it promoted unsafe practice such as interviewing in waiting rooms, it promoted a lack of privacy, resources were not improved when NEAT was implemented, and had the potential to lead to inappropriate discharge plans.

“It places undue pressure on staff for no other reason than throughput. It does not facilitate the training of (nursing and allied health) students and treats patients like they are a NEAT time bomb ready to explode at 4 hours and 1 minute. I get constant calls from people about a breach (a four hour time limit not being met), which only wastes time I do not have” (Respondent 44).

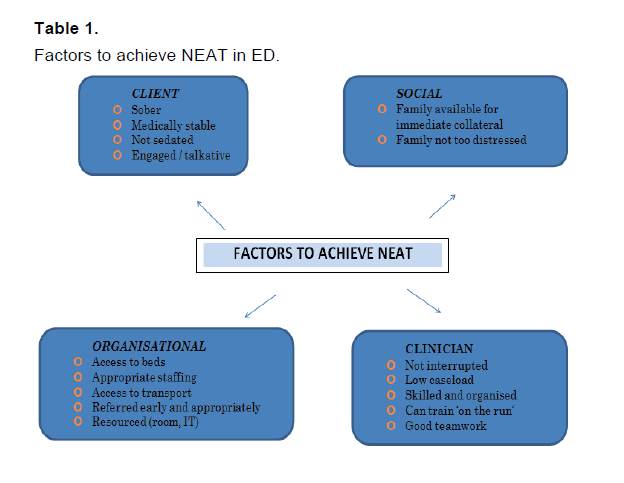

Participants were able to highlight a number of factors in this study that can impact on their ability to achieve NEAT. This included: intoxication or sedation of patient, level of medical intervention required, bed access, distressed relatives, obtaining collateral information, busy workload, paperwork / administration responsibilities, and delay in referral.

Discussion

It is apparent that NEAT has affected psychiatric assessment in the ED in both positive and negative ways. The success or otherwise of achieving NEAT while minimising its impact on ED mental health patients is dependent on a number of factors that will not always be readily available (Table 1).

Conclusion

In principle NEAT has the potential to prevent access block and ensure patients do not spend hours in EDs and waiting rooms unnecessarily. It has also promoted more streamlined practice and communication within EDs. However, the pressure to rush mental health assessments, partake in unsafe practice, make training a lower priority, and spend less time with clients and families cannot be viewed as a positive step forward. The profile of a patient presentation likely to smoothly meet NEAT, is incongruent with the type of mental health presentation ED will be required to assess.

The full study this commentary is based on can be viewed at;

Donley, E., & Sheehan, R. (2015). Impact of National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) on psychiatric risk assessment in hospital Emergency Departments. International Journal Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience.

References

- Chang, G., Weiss, A., Orav, E., Jones, J., Finn, C., Gitlin, D., et al. (2010). Hospital Variability in Emergency Department Length of Stay for Adult Patients Receiving Psychiatric Consultation: A Prospective Study, Annals of Emergency Medicine, 58(2), 127-136.

- Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A.J., & Turner, L.A. (2007). Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, (2), 112-133.

- Maumill, L., Zic, M., Esson, A., Geelhoad, G., Borland, M., Johnson, C., et al. (2013). The National Emergency Access Target (NEAT): can quality go with timelines? Medical Journal of Australia, 198(3), 153-157.

- Slade, E., Dixon, L., & Semmel, S. (2010) Trends in the duration of emergency department visits, 2001-2006. Psychiatric Service,61, 878-884.

- Zun, L. (2012). Pitfalls in the care of the psychiatric patient in the emergency department. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 43(5), 829-835.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 10102

- [From(publication date):

December-2015 - Jul 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9164

- PDF downloads : 938