Research Article Open Access

Impact of Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety on Intergenerational Trauma and Substance Use in an Aboriginal Sample

Teresa Naseba Marsh1*, Nancy L Young1, Sheila Cote-Meek2, Lisa M Najavits3and Pamela Toulouse4

1Interdisciplinary Rural and Northern Health, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON, Canada

2Academic and Indigenous Programs, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Canada

3Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, USA

4School of Education (English Concurrent), Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada

- *Corresponding Author:

- Teresa Naseba Marsh

Interdisciplinary Rural and Northern Health Laurentian University

Sudbury, ON, Canada

Tel: +1-705-626-3367

E-mail: TMarsh@Laurentian.ca

Received date: Jan 25, 2016; Accepted date: June 20, 2016; Published date: June 27, 2016

Citation: Marsh TN, Young NL, Meek SC, Najavits LM, Toulouse P (2016) Impact of Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety on Intergenerational Trauma and Substance Use in an Aboriginal Sample. J Addict Res Ther 7:284. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.1000284

Copyright: © 2016 Marsh TN, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to explore whether the blending of traditional Indigenous healing practices and a mainstream treatment model, Seeking Safety, resulted in a reduction of Intergenerational Trauma (IGT) symptoms and Substance Use Disorders (SUD).

Methods: A mixed-methods design was used to evaluate the impact of a 13 week Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety implementation project with one group of 12 Aboriginal women and one group of 12 Aboriginal men (n=24). Semi-structured interviews and focus groups were conducted at the end of treatment. Data were collected pre- and post-implementation using the following assessment tools: the Trauma Symptom Check-list-40 (TSC-40), the Addiction Severity Index-Lite (ASI-Lite), the Historical Loss Scale (HLS), and the Historical Loss Associated Symptom Scale (HLASS). The effectiveness of the new program was assessed using paired t-tests, with the TSC-40 as the main outcome.

Results: A total of 17 participants completed the study. All demonstrated improvement in the trauma symptoms, as measured by the TSC-40, with a mean decrease of 23.9 (SD=6.4, p=0.001) points, representing a 55% improvement from baseline. Furthermore, all six TSC-40 subscales demonstrated a significant decrease (anxiety, depression, sexual abuse trauma index, sleep disturbance, dissociation and sexual problems). Historical grief was significantly reduced and historical loss showed a trend on reduction. Substance use did not change significantly as measured by the ASI-Lite alcohol composite score and drug composite score, but one third of the sample did not report substance use at baseline and thus these variables were underpowered. Satisfaction was high. Participants who dropped out prior to session 10 were more severe than those who stayed in treatment.

Conclusion: Evidence from this mixed-methods study indicates that blending Indigenous Healing with the Seeking Safety model was beneficial in reducing trauma symptoms and historical grief. The combination of traditional and mainstream healing methods has the potential to enhance the health and well-being of Aboriginal people.

Keywords

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); Substance use disorder (SUD); Intergenerational trauma (IGT); Blended implementation; Two-eyed Seeing; Seeking safety; Traditional healing practices; Decolonizing methodologies; Indigenous worldviews; Sharing circles; Elders

Introduction

The impact of the colonization of Aboriginal peoples in Canada has resulted in loss of traditional ways, culture, and land [1-3]. The impact of these losses has caused trauma that has been passed down over generations [1-4]. Many of those affected have turned to alcohol and substances to cope [1,5-8]. This paper reports on the evaluation of a relatively new treatment strategy to promote healing among Aboriginal people in Northern Ontario who suffer from intergenerational trauma (IGT) and substance use disorder (SUD).

It is important to understand the larger context before embarking on the evaluation of treatment. Between 1831 and 1996 Aboriginal children in Canada were forced to attend Indian residential schools, which restricted the practice of traditional ceremonies and hindered their ability to speak traditional languages. The impact of residential schools resulted in the devastation of a nation that was previously sovereign and independent, with established traditional systems to solve conflicts and rectify issues [1,8-10].

The brutal experiences in these schools were reported by survivors as a force that shaped their lives and future parenting styles.12 Internalized oppression became the hallmark of many as they expressed hatred toward themselves, their culture, and traditional values and beliefs [5,6,8,11,12], leading many to later struggle with identity issues. Chansonneuve [1] explained that some residential school survivors express their grief as lateral violence directed toward family and community members, thereby creating intergenerational cycles of abuse that can resemble many of the experiences at the residential schools [13]. As a result, many residential school survivors suffer from mental health challenges. They have also suffered shame, guilt, low self-esteem, and confusion from learning another culture and not knowing how to join the two cultures that they know [14-16]. Many of these Indigenous people turned to alcohol, drugs, gambling, crime or other methods to lessen their internalized hate, guilt, pain and trauma.

The internalization of oppression, shame and guilt created violence among and within Indigenous survivors. This led to deeper and more pervasive community-level mental health problems that continue today in many Aboriginal communities [12,17,18]. It is welldocumented that people sexually abused as children are at increased risk for major psychiatric difficulties, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression, SUD, self-harm, suicide, sexual problems, difficulties with self-soothing, difficulties with self-esteem, and perpetuating sexual acts against others [6,12,19-22]. Considering the significant role that (IGT) plays in the lives of Aboriginal peoples, it was important to explore ways in which the cycle of trauma, stress and self-destructive behaviours could be halted [6,12,23-25].

Many Indigenous researchers, traditional healers, and Elders agree that healing IGT and SUD in Aboriginal peoples is rooted in cultural interventions and recovery of identities [15,26-28]. Gone [17], Stewart [18], Duran [29], Duran et al. [30] and McCabe [31] all argue that therapy to heal mental health issues in Indigenous peoples must incorporate cultural practices.

The Seeking Safety counseling model (SS) teaches coping skills to help heal trauma and/or SUD. It can be conducted in group or individual format by any provider, including peers ([32]; see also www.seekingsafety.org). It was developed by Najavits [32], a clinical psychologist, in the United States starting in 1992. SS has five key principles: (1) Safety as the overarching goal (helping clients attain safety in their relationships, thinking, behaviour, and emotions); (2) Integrated treatment (working on both trauma and substance abuse at the same time); (3) A focus on ideals to counteract the loss of ideals in both trauma and substance abuse; (4) Four content areas: cognitive, behavioural, interpersonal, case management; (5) Attention to clinician processes (clinicians' emotional responses, self-care, etc.).

SS model has been used successfully among many minority populations, including African-Americans, Hispanics, and Asian- Americans. It has also been translated into numerous languages with implementation in various countries [32-35]. For these reasons, this model has potential relevance to Aboriginal peoples.

The Two-Eyed Seeing approach was used to guide this research process. This approach was selected because it aligns with decolonizing and Indigenous research methodologies [27,36,37]. Many Indigenous scholars agree that the process of decolonization requires ethically and culturally acceptable approaches when research involves Indigenous peoples [36-38]. The Two-Eyed Seeing approach is consistent with Aboriginal governance, research as ceremony, and self-determination. In other words, it is consistent with the principles of ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP; [37,39,40]).

Literature Review

In this paper, the term “Aboriginal” refers to First Nations (status and non-status Indians), Métis and Inuit people as referenced in the Canadian Constitution; the term is used as a way to respect their status as the original peoples of Canada. In addition, the term Aboriginal acknowledges the shared cultural values, historical residential school experiences, and contemporary struggles with the aftermath of colonization and oppression. The word “Indigenous” will also be used interchangeably with Aboriginal. The preceding term is often most recognizable within international contexts.

Today, many Aboriginal people suffer from IGT caused by more than 400 years of systematic marginalization [41-44]. According to Gagne, IGT is the transmission of historical oppression and its negative consequences across generations [44]. Heart [24] was the first to apply the concept of IGT to the Lakota people in the United States, naming it “historical trauma”. Heart and DeBruyn [45] noted that the 1890 massacre (often referred to as the “Wounded Knee Massacre”), which occurred against the Lakota people and killed thousands, was the beginning of an over-reliance on alcohol and elevated rates of suicide, which were ways of coping with unresolved feelings of loss.

Evans-Campbell [46], a professor at the University of Washington School of Social Work and a citizen of the Snohomish Tribe of Indians, published an article delineating the nature and impact of historical trauma in Native American communities. Evans-Campbell argued that the events that give rise to historical trauma, though varied, could be viewed as sharing three broadly defining features [46]. According to her report, the events (a) were widespread amongst the Aboriginal community; (b) generated high levels of collective distress in contemporary communities; and (c) were perpetrated by outsiders, typically with destructive intent.

Inspired by the work of Herman [47], Wesley-Esquimaux and Smolewski [48] introduced a new theoretical model for trauma transmission and healing, citing the presence of complex or endemic post-traumatic stress disorders in Aboriginal cultures, which originated as a direct result of historic trauma transmission (HTT). In this new model, the authors made many observations about the nature and impact of historical trauma on Aboriginal peoples of Canada [49]. They described their model of trauma transmission as follows:

The trauma memories are passed to next generations through different channels, including biological (in hereditary predispositions to PTSD), cultural (through story-telling, culturally sanctioned behaviours), social (through inadequate parenting, lateral violence, acting out of abuse), and psychological channels (through memory processes) [48].

Challenges of SUD in aboriginal peoples

Most indigenous communities struggle with substance use [1,7,25,49-51]. Approximately one-third (35.3%) of First Nations adults were abstinent from alcohol in RHS 2008/10, a percentage higher than that observed in the general Canadian population [52]. However, of First Nation adults who do drink, almost two-thirds met the criteria for heavy drinking. First Nations males appear to be at higher risk of heavy drinking (and related harms) compared to females [52]. Heavy drinking is associated with a range of harmful effects, including various health conditions and traumatic injury. Greater efforts are needed to encourage moderate drinking among First Nations adults who choose to consume alcohol, and abstinence among those who have developed alcohol dependence [52]. The development of SUD is often associated with trauma and is thought to be an attempt to selfmedicate in order to relieve the physical and emotional pain of the trauma [6,12,32,33]. Substance use in response to stress is well documented, as many people have reported using alcohol after a traumatic event to relieve anxiety, irritability and depression [53]. Many Aboriginal communities have high rates of SUD that have been attributed to intergenerational impacts of trauma experienced by previous generations in residential schools (1). Substance use is described by many scholars and researchers as a coping strategy; it has been well documented in students of residential schools and continues to this day in many Aboriginal communities [1,7,12,29].

Corrado and Cohen [54] completed a review of case files of former Aboriginal residential school survivors who had undergone clinical assessments in British Columbia. Of the 127 case files reviewed, 82% reported that their substance abuse behaviours began after attending residential schools. In addition, 78.8% of these survivors had abused alcohol. This coincides with research that shows a connection between post-traumatic stress disorder and alcoholism in the Canadian Aboriginal population [23,55,56]. Corrado and Cohen [54] noted that “alcohol use disorder is strongly associated with historical loss” (p. 413), and Haskell and Randall [19] agreed with this evidence. Many concerns have been raised by clinicians, healers and caregivers over difficulties in finding culturally appropriate help for Aboriginal people in need of support for Intergenerational trauma and SUD [6,7,57]. Aboriginal people are often challenged by a lack of access to appropriate professional support after a trauma occurs or do not seek treatment, either because services are not available or due to a lack of trust, or the services offered are not socially or culturally relevant [5,58].

In response to the under-utilization of health services by Aboriginal peoples, health-care professionals have moved toward more holistic, culturally sensitive approaches, and have endeavoured to blend mainstream health-care practices with traditional Aboriginal healing practices [59,60]. For many practitioners, care incorporates sweat lodges, smudging, drumming, sharing circles, traditional healers and Elder teachings. This holistic view of mental health and addiction not only ensures that the care is culturally relevant, but also encourages connection to the community [13,29,57,61].

The seeking safety treatment model

Mainstream SUD and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment programs such as the Seeking Safety model have not been previously applied to Aboriginal populations, but have been found to be effective in a variety of other settings [32-35]. For example, Boden et al. [62] found in a randomized controlled trial that SS, either alone or combined with the antidepressant sertraline, showed significant reduction in both PTSD and alcohol use disorder, even when delivered in a partial dose amount (12 sessions). In addition, there is research to support similar efficacy of the Seeking Safety treatment in men.

In several Seeking Safety studies the Trauma Symptom Checklist- 40 (TSC-40) [63] measure was used to evaluate changes in trauma symptoms, with findings consistently evidencing reductions (e.g. [64-66]). For example a study done by Ghee et al. [64] examined the efficacy of a condensed version of Seeking Safety intervention in the reduction of trauma-related symptoms using the TSC-40 as one of the outcome tools. One hundred and four women were randomly assigned to treatment including a condensed (six-session) Seeking Safety intervention or the standard chemical dependence intervention. At baseline (n=36) the mean TSC-40 total scores of the women in the Seeking Safety group were 49.86 (SD=19.49). At post–intervention, (n=22) total TSC=40 mean scores were 18.68 (SD=19.05). Compared to the standard treatment group the baseline (n=50) mean scores were 47.96 (SD=24.47) and at post-treatment (n=18) the mean scores were 20.83 (SD=21.71) [65]. The Seeking Safety participants reported lower sexual-abuse-related trauma symptoms at 30 days post-treatment, as compared to participants who received only standard treatment [64].

Patitz et al. [65], in a pilot study, investigated the impact of Seeking Safety [33], on trauma symptoms among 23 rural women with comorbid substance use and trauma. To assess the trauma symptoms the Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI; [66]) was utilized pre- and postintervention. The Seeking Safety groups occurred over 12 weeks, and 24 sessions were offered. There were no dropouts. All pre-intervention TSI mean t-scores fell approximately one standard deviation above the mean of the nonclinical norm group, except for the anger/irritability subscale, which was in the normal range. The mean scores on all TSI subscales decreased significantly from pre- to post-intervention. Participants also showed changes across all trauma symptoms, including highly impairing symptoms, such as hyper-arousal, depression, flashbacks, dissociation and avoidance.

The blending of Aboriginal and Western research methods, knowledge translation, and program development has been called Two-Eyed Seeing [67]. The concept of Two-Eyed Seeing originated through the work of Marshall from Eskasoni First Nation, along with Dr. Bartlett at Cape Breton University’s Institute for Integrative Science and Health/Toqwa’tu’kl Kjijitaqnn [68]. Two-Eyed Seeing is explained by Elder Marshall as: “to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing, and to see from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and to use both of these eyes together” [68]. Two-Eyed Seeing recognizes Indigenous knowledge as a distinct and whole knowledge system that can exist side by side with mainstream (Western) science [67,68]. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s (CIHR) Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health has adopted the concept of Two-Eyed Seeing with the goal of transforming Indigenous health and features it prominently in its vision for the future [69].

The present study sought to address this question: Is the integration of Indigenous healing into the Seeking Safety model effective for group treatment for concurrent IGT and SUD in Aboriginal women and men? A mixed-methods approach was selected for this study. This paper presents the quantitative results; the qualitative results have been published separately [12]. The trauma symptoms were measured by the TSC-40 composite score. Substance use was measured by the ASI-Lite composite scores for alcohol and drugs. Both are well-validated tools to measure substance use and trauma symptoms [70-72]. To further understand changes in trauma symptoms within the specific context of Aboriginal peoples’ experiences of loss of culture, identity, pride, land and language, we also used the culturally sensitive HLS and HLASS scales to capture and explore these changes in trauma symptoms [73].

Methods

Aboriginal traditional healing practices guided this research from inception. It was critical, therefore, to conduct this research in an honorable, honest, respectful and humble manner; thus, cultural informants (Elders, an Aboriginal advisory group, Aboriginal scholars and clinicians) were invited into this process as consultants and experts. The teachings, wisdom, guidance and feedback of these experts were critical to the success of this research.

Four facilitators and two students were selected to lead the Seeking Safety sharing circles for this implementation project. The Elders advised that all facilitators should be Indigenous and have experience working with Aboriginal peoples. All four facilitators had previous experience working with women and men who suffer from trauma and SUD. The facilitators were trained in group facilitation and the delivery of the Seeking Safety sharing circles. The training lasted for one week, eight hours per day, and consisted of didactical, experiential and smallgroup learning, as well as practice sessions which were video recorded. Discourse on sharing circle protocols, methods, process, therapeutic use of self, and expectations was also included.

Participants

Participants were recruited by counsellors and health care workers and health care professionals on reserves in the surrounding areas of Sudbury. A convenience sampling approach was used to recruit 24 participants (12 women and 12 men) who self-identified as Aboriginal and who were willing to accept an implementation project where Indigenous traditional healing practices were incorporated. Most of the participants were in early recovery and connected with these treatment agencies. After referrals were made, appointments were set with prospective participants. Written consent from all participants was obtained during their initial interviews. All participants resided offreserve in Northern Ontario and were between the ages of 24 and 68 years (with an average age of 35 years). Of the 24 participants, 16 identified as Ojibway, two as Cree, and six as Métis. Furthermore, all participants self-reported that they had IGT and SUD. Half of the participants reported substance use in the past 30 days. In this sample there was no active psychosis, no acute withdrawal, and no current suicidality or homocidality. This study was approved by the Laurentian University Research Ethics Board in May 2013.

Data collection

The initial meeting with each participant lasted approximately 90 min. Participants were briefed and informed about the Indigenous healing and Seeking Safety implementation project, the process, and the program details. The following instruments were administered at baseline and at the end of the 13 week treatment program: ASI-Lite, TSC-40, HLS, HLASS. Also, after every Seeking Safety sharing circle, participants were given an end-of-session questionnaire to report on their satisfaction with the program [12,33].

The TSC-40 [63] is a relatively brief, 40 items, self-report instrument consisting of six subscales (Anxiety, Depression, Dissociation, Sexual Abuse Trauma Index, Sexual Problems, and Sleep Disturbance) that measure symptoms associated with childhood or adult traumatic experiences [63]. Items are rated according to frequency of occurrence over the prior two months, using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. The composite TSC-40 scores have a maximum possible range from 0 to 120, with high scores indicating worse outcomes (more symptoms). The TSC-40 has predictive validity with a wide range of traumatic experiences, including sexual and emotional abuse [74-76].

The ASI-Lite is a semi-structured interview that focuses on the prior 30 days, with composite scores in seven domains: psychological, legal, medical, social, employment, alcohol, and drugs [71].

Given its wide scope, the ASI-Lite allows the researcher to obtain lifetime information about respondents’ problem behaviours, as well as problems within the previous 30 days [71].

The HLC and the HLASS capture the impacts of historical trauma. The HLASS is composed of twelve items and specifies symptoms identified by participants. Response categories range from 1 (several times a day) to 6 (never) . This scale has high internal reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha scores of 0.94 for the Historical Loss Scale and 0.90 for the HLASS [74]. Finally, the SS End-of-Session Questionnaire [33] was designed to capture the immediate reaction of participants to the content and traditional healing techniques in each session and was completed by participants after every session.

Gender division was maintained throughout the intervention, as requested by the Elders and Aboriginal advisory group. During these sharing circles, participants were asked to talk about their experiences [33].

Indigenous healing and seeking safety sharing circles

The goal of providing a culturally appropriate healing method was achieved by incorporating traditional healing practices and ceremonies with the Seeking Safety model. An integration example was the use of the SS grounding technique in conjunction with the sweat ceremonies. A sweat ceremony is a cultural practice performed in a heated, domeshaped lodge that uses heat and steam to cleanse toxins from the mind, body, and spirit. Seeking Safety uses grounding and centering techniques in the group sessions. This grounding technique helps traumatized individuals connect to the present, calm the nervous system, and help with difficult memories. Therefore grounding was integrated during the sweat ceremonies and during the sharing circles.

Smudging was incorporated at the opening of each session with the burning of a sacred herb (sage) in a small bowl to purify the participants, leaders and the therapeutic space. Soon after, a Seeking Safety topic was introduced, and the sacred medicine aroma would enhance the connection with the information. Drumming, the use of ceremonial drums and songs as a way to connect with the Creator and spirit was often accompanied by a Seeking Safety quotation. Sharing circles were the groups offered during a Seeking Safety session. The presence of the Elders and their teachings blended well with all the Seeking Safety topics. One such example was when the Seeking Safety topic "anger" was discussed. The Elders' teachings on this topic were about the power of the sacred fire. The Elders encouraged the participants to be their own fire keepers and to make sure that the fire brought them warmth and not destruction [7,12,38].

25 Seeking Safety sharing circles were offered over 13 weeks following the initial meetings. The sessions for 12 men took place at Rockhaven Recovery Home for Men, and the sessions for 12 women took place at the N’Swakamok Native Friendship Centre. We conducted all 25 Seeking Safety topics [33]. The hand-outs were printed and given to clients at every session. Topics were scheduled as per the Seeking Safety Manual [33]. The number of participants who attended varied. During the 25 sharing circles, an average of nine participants out of the 12 registered participants attended. Beverages and a light snack were offered during every circle. Also, at the completion of the program, the participants were advised about aftercare. They were all encouraged to return to their referring treatment agencies and to continue to apply the strategies and knowledge they received. They were encouraged to use the resource list that they received at the beginning of the project. Participants were also encouraged to continue their relationship with the Elders [6,12].

Data Analysis

The results of the baseline questionnaire were analyzed using pooled data from all participants (n=24) to describe the sample. Changes as a result of the implementation project were measured by comparing scores at baseline (collected within one month before the intervention) to post-intervention scores (collected within two weeks of completing treatment) for the subset of participants who completed at least 10 of the 25 intervention sessions. The main treatment outcomes were current (i.e., past 30 days) trauma symptom severity as measured by the TSC-40 composite score and drug and alcohol problems measured by the ASI- Lite composite score. Additional outcomes were historical loss and grief measured using the HLC and HLASS. Outcomes were analyzed using paired t-tests.

Additional analyses were included both to provide context to understand the main analyses and to explore unexpected observations. These analyses were considered exploratory; accordingly, the analysis was restricted to descriptive statistics. In addition, the factors associated with non-completers were examined. Understanding factors that affect non-completion assists in identifying those who are best suited for the program. To detect predictors of non-completion, scores on the same instruments were compared for participants who completed the study to those who did not, on variables assessed at baseline.

Results

Demographics

At baseline, 12 Aboriginal males (n=12) with an average age of 39.0 years (S.D. 14.3) and 12 females (n=12) with an average age of 37.5 years (SD 10.4) entered the 13 week Indigenous healing and Seeking Safety implementation project. Seventeen of the 24 participants completed ten or more sessions of the program.

In the post-intervention group, the mean age of the eight retained males was 40 years (SD 14.7). The mean age of the nine females retained was 37.2 years (SD 10.8). There were no participants who selfidentified as non-Aboriginal. Further baseline demographic data is summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Baseline All (n=24) | Completers (data at baseline) (n=17) | Non-Completers (data at baseline) (n=7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | Males (n=12) | Males (n=8) | Males (n=4) |

| Mean 39.75 | Mean 41 | Mean 37.25 | |

| SD 14.3 | SD14.68 | SD 15.31 | |

| Females (n=12) | Females (n=9) | Females (n=3) | |

| Mean 37.5 | Mean 37.22 | Mean 38.33 | |

| SD 10.41 | SD 10.84 | SD 11.15 | |

| Female/Male (%) | 12 Female (50%) | 9 Female (75%) | 3 Female (25%) |

| 12 Male (50%) | 8 Male (67%) | 4 Male (33%) | |

| Relationship Status | |||

| Single | 17 (71%) | 10 (59%) | 7 (100%) |

| Divorced/separated | 3 (12%) | 3 (18%) | 0 |

| Married/partner | 4 (17%) | 4 (24%) | 0 |

| First Nation | 21 (88%) | 15 (88%) | 6 (86%) |

| Metis | 3 (12%) | 2 (12%) | 1 (14%) |

| Education | |||

| Less than HS | 9 (38%) | 7 (41%) | 2 (29%) |

| Finished HS | 6 (25%) | 3 (18%) | 3 (43%) |

| Post-Secondary | 9 (38%) | 7 (41%) | 2 (29%) |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 5 (21%) | 3 (18%) | 2 (29%) |

| Disability | |||

| Other Social Benefits | 19 (79%) | 14 (82%) | 5 (71%) |

| Legal Status | |||

| Probation | 8 (33%) | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Children’s Aid | 6 (25%) | 5 (29%) | 1 (14%) |

Table 1: Baseline demographics of all participants - completers and non-completers,(Completers are participants who completed 10 or more sessions).

Main outcomes: Trauma symptoms

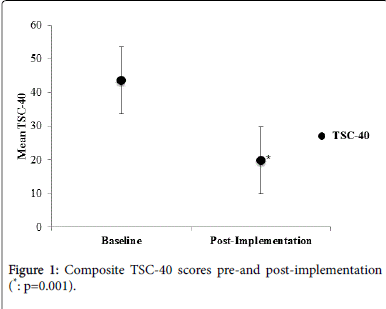

The main outcome was the severity of trauma symptoms, measured by the TSC-40 before and after participation in the research project. As mentioned, all of the participants reported that they viewed their trauma symptoms as intergenerational in nature. The 24 participants who entered the implementation program had a total TSC-40 mean score of 40.7 (20.2) at baseline. The 17 participants who completed at least 10 of the 25 sessions had a mean score of 43.7 (21.6) at baseline and 19.8 (15.2) at the end of treatment. The reduction in these composite scores was statistically significant (p=0.001) and is shown in Figure 1.

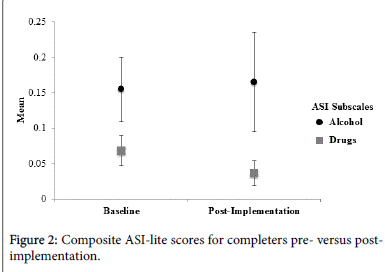

The change occurred without an increase in severity of the mean alcohol and drug ASI-Lite scores, supporting the conclusion that the participants were not triggered to substantial relapse through the treatment process (Figure 2).

The TSC-40 subscales verified a reduction in the severity of symptoms on all sub-scales: dissociation, anxiety, depression, SATI, sleep disturbance, and sexual problems. (The sub-scale results for the 17 participants who completed the 13 week Indigenous healing and Seeking Safety implementation project are presented in Table 2).

| Baseline | Post-Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSC Subscales | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Dissociation | 7.8 | 5 | 3.8 | 3.4 | p=0.027 |

| Anxiety | 9.2 | 5.8 | 3.5 | 2.8 | p=0.001 |

| Depression | 11.2 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 3.5 | p=0.000 |

| SATI | 7.4 | 4 | 3.7 | 3.9 | p=0.0011 |

| Sleep Disturbance | 9.4 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 3.4 | p=0.003 |

| Sexual Problems | 5.1 | 4 | 2.6 | 4.1 | p=0.037 |

Table 2: Changes in specific trauma symptoms for completers pre- versus post-Implementation (TSC-40 Subscale scores).

Substance use disorder

Alcohol and drug use was measured by the ASI-Lite pre and post. The composite ASI-Lite scores for the 17 participants who completed the program had a mean alcohol score of 0.16 (0.19) at baseline and 0.17 (0.29) at the end of treatment; and drug scores of 0.068 (0.088) at baseline and 0.037 (0.07) at the end of treatment. There was no statistically significant change in the alcohol or drug ASI-Lite composite scores (Alcohol: p=0.90; Drugs: p=0.26); but we note that only n=11 participants reported any substance use at baseline, thus creating a floor effect and limited statistical power to evaluate these variables. An increase of 0.1 or greater would have been considered clinically significant for the ASI scores [72]. These results are displayed in Figure 2.

Specific trauma symptoms improved post-intervention

To further understand the improvement, the subscales of the TSC-40 for each symptom group were examined. Completers of the project showed reductions in severity of all six symptom domains within the TSC-40 (Table 2).

Aboriginal context and trauma symptom improvement

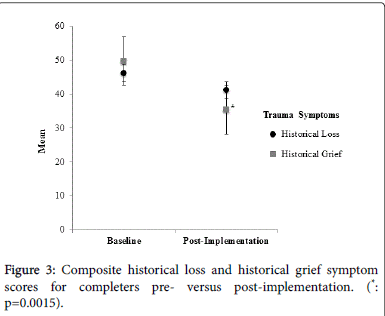

The HLS and HLASS were administered pre- and post to explore the relationship between their historical context and the symptom expression. Completers of the project showed a significant reduction in historical grief symptoms (HLASS; p=0.0015) and a trend towards reduction in historical loss symptoms (HLS; (p=0.079). The historical grief scores at baseline were 49.70 (17.22) and 35.29 (10.86) postimplementation; and the historical loss mean scores were 46.11 (16.01) and 41.23 (13.52) respectively. This aspect of the intervention was explored in more depth in the qualitative analysis [12] (Figure 3).

Satisfaction with the seeking safety sharing circles

There was a high degree of acceptance of the Indigenous healing and Seeking Safety implementation project. All of the 24 participants who entered the program were positive about the blended implementation approach. Mean ratings on the SS End-of-Session Questionnaire provided information about the specific aspects of treatment that patients found most and least helpful. Participants were asked to answer six questions with six sub-questions using a four-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a great deal) (33). Mean (SD) results were “Helpfulness of the session” 2.76 (SD=0.56); “How helpful was the topic?” 2.81 (SD=0.51); “How helpful was the hand-out?” 2.81 (SD=0.48); “How helpful was the quotation?” 2.67 (SD=0.69); “How helpful was the therapist?” 2.80 (SD=0.52); “How much did today’s session help you with your PTSD?” was 2.61 (SD =0.80), “How much did today’s session help you with your substance use?” was 2.61 (SD=0.84); and “How much of what you learned will you use?” 2.77 (SD=0.58). Additional qualitative questions and their results are described in a separate paper (12).

Predictors of dropout

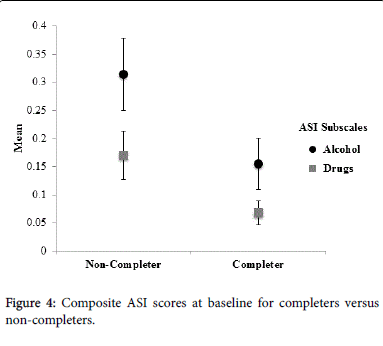

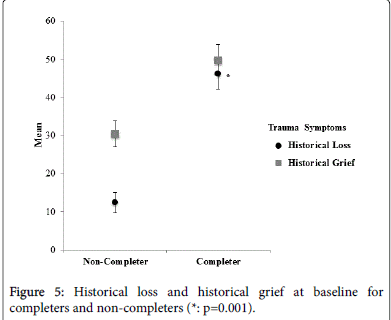

Participants with more severe drug problem on the ASI-Lite were less likely to complete the program (p=0.027), see Figure 4), but completers and non-completers did not differ in alcohol ASI scores. Treatment non-completers attended either four or five sessions whereas treatment completers attended between 10 and 25 sessions. Treatment completers exhibited more severe symptoms on the HLASS compared to non-completers at baseline. For example, at baseline the 17 treatment completers had historical loss mean scores of 46.188 (SD=16.015) and historical grief mean scores of 49.705 (SD=17.226). The mean scores for the historical loss for non-completers were 44.57 (SD=13.89; p=0.82), and the historical grief mean scores were 30.4 (SD=9.05; p=0.001).

Discussion

This study sought to identify whether Indigenous traditional healing practices incorporated into the Seeking Safety treatment model would be helpful to Aboriginal women and men with IGT and SUD. This blended implementation project evidenced significant change on the main outcome measure, the TSC-40, a measure of trauma symptoms, as well as all six of its subscales among the participants who completed the program. The results of this study are similar to results in other Seeking Safety studies in which the TSC-40 was used to measure changes in trauma symptoms [64,65], also showing significant improvement. However, the drop-out rate in Ghee et al. [64], for example, was slightly higher at 39 % compared to 29% in this study.

Results from blending Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety also showed a decrease in historical grief symptoms for completers from pre-implementation to post-implementation. Depression, anxiety, insomnia and sexual problems are all related to grief and loss [21,48,77,78]. The reduction in these subscale symptoms thus indicated that the Indigenous healing and Seeking Safety blended approach helped men and women with IGT and SUD [12]. Heart [24,25] and many other researchers in this field brought forth theories and intervention models aimed at providing Indigenous people with tools and methods to address the IGT [1,7,8,13,18,27,28,30,59,79]. Stewart [18], the involvement of local communities, Elders, and traditional helpers. In a recent study, Oulanova and Moodley [80] found that integrative efforts of mental health professionals in their practice proved extremely helpful for clients. Kirmayer et al. [56] further affirm the value in offering such access to traditional ways of healing. A study done by Lowe et al. found that Aboriginal traditional healing interventions with Native American adolescents were significantly more effective at reducing substance use and related problems than non-culturally based interventions [81] (Figure 5).

An outcome of this implementation project reported in a previous paper was that five women regained custody of their children [12]. The women reported how they had numbed themselves with substances to ease the pain of missing their children. The reduction in the IGT symptoms and the understanding of both IGT and SUD supported this outcome [12].

The Elders' teachings and healing that was reported by the participants during the sweat lodge ceremonies enhanced the healing energy of the blended implementation project. Sweat Lodge ceremonies represent returning to the womb of mother earth. In the process, participants were encouraged to release the suffering of the past and present and claim back the Spirit. The teachings and the support of the Elders and the facilitators contributed to the reduction in trauma symptoms. The hallmark of Seeking Safety is to encourage safety and self-care so that a space can be created for healing from both IGT and SUD [32]. All of the core content in the sharing circles was delivered to promote knowledge and understanding so that the cause of the problem could be addressed. The traditional healing practices shared the same belief. They were implemented to help participants heal from internalized oppression, which had been causing participants to self-harm [15,26,27,35,65]. Today, many Indigenous mental health professionals and researchers have taken the lead in promoting traditional spirituality and healing along with culture. They concur that this approach is potentially beneficial in preventing and healing SUD, other addictions and suicide, as well as additional behavioural and developmental challenges that plague many Indigenous communities of North America, especially among the very young. Indigenous professionals have come to consider traditional spirituality and culture as the key appropriate responses to IGT and unresolved historical grief [29]. Many Indigenous health practitioners integrate traditional spirituality and culture into their therapy or develop professional practices from within traditional culture and its spirituality. This movement is included in therapeutic interventions and individual counseling [29], small group psycho-educational interventions [24,25], larger scale addiction recovery programs [82], and suicide prevention programs [83].

The majority of the participants in this study presented with a history of traumatic experiences, including sexual abuse, family violence, multiple losses, and a history of multiple substance use. This sample comprised a majority of participants in early recovery and a smaller group of people who were still struggling with current substance use. The completers who initially struggled with SUD showed a reduction post- implementation, whereas the noncompleters compared with completers had more severe problems with drug use. These findings are not consistent with other findings in the literature which indicate that participants treated with Seeking Safety were more likely to benefit if they had more severe SUD [35,64].

This study had several limitations that deserve consideration. First, it is important to acknowledge that this study did not include a control group. Also, the sample size was small and was not based on power analysis. Generalizations beyond the study participants must be made with caution. In particular the assessment of alcohol and drug use was compromised by even lower power than the other measures due to a substantial proportion (one-third) not reporting any alcohol or drug use at baseline. Furthermore, all of the data in this study was selfreport. While this is essential to obtain their perspectives, it may result in under-reporting of symptoms due to fears of stigmatization, shame and guilt connected to both disorders. Thus, the results are considered conservative, with the potential for a larger effect to be observed if these biases could be eliminated. Furthermore, differences in outcomes may have been caused by pre-existing differences in amount of use and levels of support, understanding, and education about both disorders [6,12,21]. Many of the participants in this study did not understand that substance use is connected to IGT symptoms. One of the strengths of this project was their increased recognition of this and their learning of specific coping skills to manage these issues. The very strong quantitative satisfaction data from this study helps speak to what we found in our qualitative results, which was that they reported attaining new insight and knowledge; they felt validated and understood, stayed in the program and received relief and healing [12]. Further research with a larger sample size and a recruitment strategy design is necessary to examine the factors that affect the effectiveness of this blended approach for the treatment of both disorders. Lastly, the experiences and views of the participants may not be representative of Aboriginal people elsewhere across different regions. The assessment tools were validated instruments, but it is possible that some information and cultural aspects could have been missed because of limitations in tools.

Conclusion

Evidence from this study suggests that this Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety implementation project, coupled with the Two-Eyed Seeing approach and principles, was helpful in relieving Aboriginal men and women of the debilitating effects of trauma symptoms, which were intergenerational in nature, and with no worsening in their SUD. The reduction in historical grief and the high level of satisfaction and attendance were also notable. There is a definite need for future studies to take this work to the next scientific step, such as a randomized controlled trial, so as to continue to understand the impact of Aboriginal practices combined with Western treatment. Social and political awareness should inform how treatment for mental health and SUD is researched and delivered. Research focusing on factors that enhance resilience and mental health is critical as Aboriginal peoples and communities continue on the pathway to Minobimaadizi, “living the good life.”

References

- Chansonneuve D (2007) Addictive behaviours among aboriginal people in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Fontaine T (2010) Broken circle: The dark legacy of Indian residential schools: A memoir. Victoria, BC: Heritage House.

- Milloy JS (1999) A national crime: The Canadian government and the residential school system 1879-1986. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press.

- Miller CL, Pearce ME, MoniruzzamanAkm, Thomas V, Chief Christian W, et.al. (2011) The Cedar Project: Risk factors for transition to injection drug use among young, urban Aboriginal people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183: 1147-1154.

- Marsh TN, Coholic D, Cote-Meek S, Najavits LM (2015) Blending Aboriginal and Western healing methods to treat intergenerational trauma with substance use disorder in Aboriginal peoples who live in North-eastern Ontario, Canada. Harm Reduction Journal, (in press).

- Marsh TN, Cote-Meek S, Young NL, Najavits LM, Toulouse P (2015) The application of Two-Eyed Seeing decolonizing methodology in qualitative and quantitative research for the treatment of intergenerational trauma and substance use disorders. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14: 1-13.

- Menzies P (2014) Intergenerational Trauma. In P. Menziesand L. Lavallee (Eds.), Journey to healing: Aboriginal people with addiction and mental health issues: What health, social service and justice workers need to know? Toronto, ON: CAMH Publications.

- Waldram JB (2008) The models and metaphors of healing: Introduction. In J. B. Waldram, Aboriginal healing in Canada: Studies in therapeutic meaning and practice. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Cote H, Schissel W(2008) Damaged children and broken spirits: A residential school survivor story. In C. Brooks and B. Schissel (Eds.), Marginality and condemnation: An introduction to critical criminology. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

- Chrisjohn R, Young S, Maraun M (2006) The circle game: Shadows and substance in the Indian residential school experience in Canada. Penticton, BC: Theytus Books Ltd.

- Troniak S (2011) Addressing the legacy of residential school.

- Marsh TN, Cote-Meek S, Young NL, Najavits LM, Toulouse P (2016) Indigenous healing and seeking safety: A blended implementation project for intergenerational trauma and substance use disorders. The International Indigenous Policy Journal 7.

- McCormick R (2009) Aboriginal approaches to counselling. In L. J. Kirmayerand G. G. Valaskakis, Healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

- Blackstock C (2006) Keynote address at the rights of a child conference at Brock University in St. Catherines, Ontario.

- Gone JP (2009) A community-based treatment for Native American historical trauma: Prospects for evidence-based practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 77: 751-762.

- Yazzie R (2000) Indigenous peoples and postcolonial colonialism. In M. Battiste, Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- Gone JP (2008) The pisimweyapiy counselling centre: Paving the red road to wellness in northern Manitoba. In J. B. Waldram (Ed.), Aboriginal healing in Canada: Studies in therapeutic meaning and practice. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Stewart S (2008) Promoting indigenous mental health: Cultural perspectives on healing from native counsellors in Canada. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education 46: 12-19.

- Haskell L, Randall M (2009) Disrupted attachments: A social context trauma framework and the lives of Aboriginal people in Canada. Journal of Aboriginal Health 5: 48-99.

- Herman JA (1997) Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Marsh TN (2010) Enlightenment is letting go! Healing from trauma, addiction, and multiple loss. Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse.

- Maté G (2009) In the realm of hungry ghosts: Close encounters with addictions. Toronto, ON: Vintage Canada.

- Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H (2009) Intergenerational trauma: Convergence of multiple processes among First Nations peoples in Canada. Journal of Aboriginal Health: 5, 6-47.

- Brave Heart MYH (1998) The return to the sacred path: Healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the Lakota through a psycho-educational group intervention. Smith College Studies in Social Work 68: 287-305.

- Brave Heart MYH (2004) The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationship to substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. In E Nebelkopfand M Phillips (Eds.), Healing and mental health for Native Americans: Speaking in red. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Hill DM (2009) Traditional medicine and restoration of wellness strategies. Journal of Aboriginal Health 5: 26-42.

- Kovach M (2009) Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Mehl-Madrona L (2009) What traditional indigenous elders say about cross-cultural mental health training. Explore (NY) 5: 20-29.

- Duran E (2006) Healing the soul wound: Counseling with American Indians and other Native peoples. New York, NY: Teacher’s College.

- Duran E, Firehammer J, Gonzalez J (2008) Liberation psychology as the path toward healing cultural soul wounds. Journal of Counselingand Development 86: 288-295.

- McCabe Glen (2008) Mind, body, emotions and spirit: reaching to the ancestors for healing. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 21: 143-152.

- Najavits LM (2007) Seeking Safety: An evidence-based model for trauma/PTSD and substance use disorder. In KWitkiewitzand GA Marlatt, Therapist’s guide to evidence-based relapse prevention. San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

- Najavits LM (2002) Seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Najavits LM (2009) Seeking safety: An implementation guide. In A. Rubin and D. W. Springer (Eds.) The clinician’s guide to evidence-based practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Lenz AS, Henesy R, Callender K (2016) Effectiveness of Seeking Safety for Co-Occurring Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Substance Use. Journal of Counselling and Development 94: 51-61.

- Smith LT (1999) Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. London, ENG: Zed Books.

- Wilson S (2008) Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

- Menzies P, Bodnar A, and Harper V (2010) The role of the elder within a mainstream addiction and mental health hospital: Developing an integrated model. Native Social Work Journal 7: 87-107.

- First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) (2013). The First Nations principles of OCAP™.

- National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) (2005) Ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP) or self-determination applied to research. A critical analysis of contemporary First Nations research and some options for First Nations communities. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Centre.

- Abdullah J, Stringer E (1999) Indigenous knowledge, indigenous learning, indigenous research. In L Semaliand JL Kincheloe (Eds) What is Indigenous knowledge? Voices from the academy. New York, NY: Falmer Press.

- Armitage A (1995) Comparing the policy of aboriginal assimilation. Vancouver, BC: University of British Colombia Press.

- Couture J (2000) Native studies and the academy. In GJ Dei, BL Hall, and DGoldin Rosenberg, Indigenous knowledge in global contexts: Multiple readings of our world. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Gagne M (1998) The role of dependency and colonialism in generating trauma in First Nations citizens. In Y. Danieli, International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Brave Heart MYH, DeBruyn LM (1998) The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaskan Native Mental Health Research 8: 56-78.

- Evans-Campbell T (2008) Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multi-level framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence23: 316-338.

- Herman J (1997) Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence, from domestic abuse to political terror. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Wesley-Esquimaux CC, Smolewski M (2004) Historic trauma and Aboriginal healing. Ottawa, Canada: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Kawamoto WT (2001) Community mental health and family issues in socio-historical context: The confederated tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians. American Behavioural Scientist 44: 1482-1491.

- Mussell WJ (2005) Warrior-caregivers: Understanding the challenges and healing of First Nations men: A resource guide. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Spittal PM, Craib KJP, Teegee M (2007) The Cedar project: Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among young Aboriginal people who use drugs in two Canadian cities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 66: 226-40.

- First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) (2012) First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS)2008/10: National report on adults, youth and children living in First Nations communities. Ottawa, ON: IGC.

- Volpicelli J, Balaraman G, Hahn J, Wallace H, Bux D (1999) The role of uncontrollable trauma in the development of PTSD and alcohol addiction. Res Health 23: 256-262.

- Corrado RR, Cohen IM (2003) Mental health profiles for a sample of British Columbia’s Aboriginal survivors of the Canadian residential school system. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Assembly of First Nations (2007) First Nations regional longitudinal health survey: Results for adults, youth and children living in First Nations communities (RHS). Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Kirmayer L, Simpson C, Cargo M (2003) Healing traditions: Culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australasian Psychiatry (Supplement) 11: 15-23.

- McCormick RM (1996) Culturally appropriate means and ends of counselling as described by the First Nations people of British Columbia. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 18: 163-172.

- Kirmayer LJ , Brass GM, Tait CL (2000) The mental health of Aboriginal peoples: transformations of identity and community. Can J Psychiatry 45: 607-616.

- Martin-Hill D (2003) Traditional medicine in contemporary contexts: Protecting and respecting Indigenous knowledge and medicine. Ottawa, ON: National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- Rojas M, Stubley T (2014) Integrating mainstream mental health approaches and traditional healing practices. A literature review. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 1: 22-43.

- Poonwassie A, Charter A (2005) Aboriginal worldview of healing: Inclusion, blending, and bridging. In R Moodleyand W West, Integrating traditional healing practices into counseling and psychotherapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Boden MT, Kimerling R, Jacobs-Lentz J, Bowman D, Weaver C, et al. (2012) Seeking Safety treatment for male veterans with a substance use disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Addiction 107: 578-86.

- Briere J, Runtz M (1996) Trauma symptom check-list 33 and 40 (TSC-33 and TSC-40).

- Ghee A, Bolling L, Johnson C (2009) Adult survivors of sexual abuse: The efficacy of a condensed Seeking Safety intervention for women in residential chemical dependence treatment at 30 days post-treatment. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 18: 475-488.

- Patitz BJ, Anderson ML, Najavits ML (2015) An outcome study of Seeking Safety with rural community-based women. Journal of Rural Mental Health 39: 54-58.

- Snyder JJ, Elhai JD, North TC, Heaney CJ (2009) Reliability and validity of the trauma symptom inventory with veterans evaluated for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 170: 256-261.

- Bartlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A (2012) Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledge and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2: 331-340.

- Iwama M, Marshall A, Marshall M, Bartlett C (2009) Two-Eyed Seeing and the language of healing in community-based research. Canadian Journal of Native Education 32: 3-23.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (2011) Knowledge translation strategy 2004-2009: Innovation in action.

- Briere J, Scott C (2006) Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP (1980) An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The addiction severity index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 168: 26-33.

- Briere J (2002) Psychological assessment of adult post-traumatic states. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X (2004) Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. Am J Community Psychol 33: 119-130.

- Binder R, McNeil D, Goldstone R (1994) Patterns of recall of childhood sexual abuse as described by adult survivors. Bulletin of American Academic Psychiatry Law 22: 357-366.

- Dutton DG (1995) Trauma symptoms and PTSD-like profiles in perpetrators of intimate abuse. J Trauma Stress 8: 299-316.

- Dutton DG, Painter S (1993) The battered woman syndrome: Effects of severity and intermittency of abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry 63: 614-622.

- Levine PA (2003) Panic, biology and reason: Giving the body its due. International Body Psychotherapy Journal 2: 2-21.

- Linklater R (2010) Decolonizing our spirits: Cultural knowledge and Indigenous healing. In S. Marcos, Women and Indigenous religions. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Lavallée L (2008) Balancing the medicine wheel through physical activity. Journal of Aboriginal Health 4: 64-71.

- Oulanova O, Moodley R (2010) Navigating two worlds: Experiences of counsellors who integrate Aboriginal traditional healing practices. Canadian Journal of Psychotherapy 44: 346-362.

- Lowe J, Liang H, Riggs C, Henson J (2012) Community partnership to affect substance abuse among Native American adolescents. American Journal of Drug Alcohol Abuse 38: 450-455.

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2007) Addictive behaviours among Aboriginal people in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde C (1998) Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry 35:191-219.

--

Relevant Topics

- Addiction Recovery

- Alcohol Addiction Treatment

- Alcohol Rehabilitation

- Amphetamine Addiction

- Amphetamine-Related Disorders

- Cocaine Addiction

- Cocaine-Related Disorders

- Computer Addiction Research

- Drug Addiction Treatment

- Drug Rehabilitation

- Facts About Alcoholism

- Food Addiction Research

- Heroin Addiction Treatment

- Holistic Addiction Treatment

- Hospital-Addiction Syndrome

- Morphine Addiction

- Munchausen Syndrome

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

- Nutritional Suitability

- Opioid-Related Disorders

- Substance-Related Disorders

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13206

- [From(publication date):

June-2016 - Jun 30, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12265

- PDF downloads : 941