Research Article Open Access

'I Don't have the Best Life': A Qualitative Exploration of Adolescent Loneliness

Karen Emma Martin1*, Lisa Jane Wood1, Stephen Houghton2, Annemaree Carroll3, John Hattie41School of Population Health, The University of Western Australia, Australia

2Graduate School of Education, The University of Western Australia, Australia

3School of Education, University of Queensland, Australia

4Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne

- *Corresponding Author:

- Karen Emma Martin

School of Population Health

University of Western Australia

35 Stirling Hwy, Crawley

WA 6009, Australia

Tel:+618 6488 1267

Fax: +618 6488 1188

E-mail: Karen.Martin@uwa.edu.au

Received Date: July 14, 2014; Accepted Date: October 16, 2014; Published Date: October 23, 2014

Citation: Martin KE, Wood LJ, Houghton S, Carroll A, Hattie J (2014) 'I Don't have the Best Life': A Qualitative Exploration of Adolescent Loneliness. J Child Adolesc Behav 2:169. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000169

Copyright: © 2014 Karen Emma Martin, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

Objectives: Loneliness is considered a significant contributor to adolescent suicidality and mental illness. This study explored the nature of loneliness, aloneness, and friendships as described by early-mid aged adolescents. Methods: In total, 33 (13 male and 20 female) adolescents (aged 10-15) from three primary and two secondary schools located in low, medium, and high socioeconomic areas in Perth, Western Australia were interviewed. Inductive analysis of verbatim transcripts incorporated constant comparative coding, thus forming conceptual categories, relationships, and theory. Results: Loneliness was identified as a multifactorial experience centering on two main constructs: 1) connectedness with friends, and 2) perception of aloneness. Qualitative insights support the concept of adolescents 'positioned' on continuums within these two constructs; 1) friendship- with connected and disconnected anchors, and 2) perception of aloneness - with positive and negative anchors. Conclusions: This study highlighted that loneliness is multidimensional and is influenced both by the existence (or not) of meaningful friendships as well as by how adolescents frame and experience being alone. Being alone can have both positive and negative associations for adolescents, and this appears to be influenced by the setting and experienced frequency of being alone. Aloneness can be buffered by friendship networks, and experienced more negatively when friendships and social connectedness are lacking. This epitomizes vulnerabilities associated with unstable friendships. Assisting adolescents to both develop secure friendships and positive attitudes towards aloneness has an important role to play in reducing adolescent loneliness as well as decreasing the risk of associated negative outcomes. These study results provide direction for practitioners in developing targeted approaches to prevent and reduce loneliness; this includes carefully considering policy and practices that could reduce (or unintentionally induce) loneliness. As the school is a setting in which adolescents are especially vulnerable to feelings of loneliness, school-based strategies could be particularly useful and wide-reaching.

Keywords

Adolescents; loneliness; Socioeconomic; Friendships

Introduction

Mental illnesses, such as mood and anxiety disorders, are experienced by nearly one in four adolescents worldwide [1]. It is well established that mental illness is strongly associated with suicide [2], which is now one of the leading causes of death in 15 to 19 year olds globally [3]. To effectively address the problem of wide-spread youth mental illness, and reduce outcomes such as suicide and lifelong comorbidities, a comprehensive understanding of factors contributing to these issues is imperative. Loneliness is considered a significant contributor to adolescent suicidality [4,5], and mental illnesses such as depression [4,6] and self-harm [7]. Other significant adverse outcomes of loneliness include risky behaviours such as recreational drug use, violence [6], eating disturbances, obesity and sleep disturbances [8], alcohol use, and somatic complaints [9].

Adolescence (defined as ages 10 – 19 [10]) is a tumultuous time, and it is not uncommon for adolescents to feel lonely intermittently (over two-thirds of youth report experiencing loneliness on occasion). However, 15 to 30% describe these feelings as persistent and painful [4,11] and for some adolescents, loneliness manifests to become a debilitating psychological condition; characterized by a deep sense of social isolation, emptiness, worthlessness and lack of control [12]. Prolonged loneliness has the potential to become chronic, especially during adolescence, when social development and identity formation become most salient [13]. The need for greater independence, primarily through closer ties with friends and peer groups [14], is a hallmark of adolescent development. This change, however, is inextricably linked with the risk of “increased feelings of separateness ... and vulnerability to emotional and social loneliness” [11]. Thus, adolescence is a time where unresolved loneliness can develop pathologically [15-17] and come to “resemble an enduring personality trait” [18].

Loneliness is seen by some researchers to be a unidimensional construct: a single entity which is the same for everyone across circumstances and causes, and measurable using a single scale [19-21]. Others see it as a multidimensional construct, with Weiss [22] proposing one of the earliest multidimensional models. This model comprised social loneliness, considered a deficit in one’s social relationships, social networks, and social supports; and emotional loneliness, which occurs through a lack of close or intimate companionship (thereby one can feel lonely even when in the company of others). More recent research suggests up to three or four factors. In one of the most comprehensive model testing studies, Goossens, and colleagues tested competing factor models on data collected from 534 mid-older aged Dutch adolescents (15-18 years) using nine different instruments (14 sub-scales). The findings supported a four-factor model representing peer or friendship-related loneliness, family loneliness, positive attitude to solitude, and negative attitude to solitude. Our own recent quantitative research [24] employing both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses using data from 1,500 adolescents, provided further support for such a multifactorial model of loneliness. This model included friendships (having reliable, trustworthy and supportive friends), isolation (having few friends or believing that there was no one around offering support), positive attitude to solitude (finding positive aspects in being alone, solitude or the capacity to be alone to enjoy self-discovery and self-realization), and negative attitude to solitude (negative aspects of being alone, feelings of emptiness, abandonment, self-alienation, meaninglessness, and existential loneliness).

Although empirical advances in the conceptualization and measurement of loneliness are valuable, as articulated by Goossens et al. [23] “current instruments may measure only a subset of the multidimensional experience of loneliness in adolescence”. Moreover, empirical measures are inherently limited in fully capturing the lived experiences of loneliness in adolescence. Qualitative research can provide insightful narrative to help explain empirical observations [25], and is able to derive a nuanced understanding of learning about how people make sense of their social and material circumstances, their experiences, perspectives and histories [26]. Further, adding depth and detail to quantitative results, qualitative data provides meanings and substance to an area of focus [27].

This current study (a formative component to the previously mentioned quantitative study [24]), explored the nature of loneliness, aloneness, and friendships as described by early- mid aged adolescents (aged 10-15). Semi-structured interviews provided rich and in-depth dialogue about the everyday experiences of loneliness for adolescents, vulnerabilities to loneliness and the variability in how loneliness is perceived and experienced.

Method

Participants and setting

The sample comprised a total of 33 (13 male and 20 female) adolescents (aged 10-15). Of these, 22 (7 male and 15 female) were early-aged adolescents (aged 10 to 12 years; Grades 5 to 7) and 11 (6 male and 5 female) were mid-aged adolescents (aged 13 to 15 years; Grades 8- 10). The participants were drawn from three primary and two secondary schools located in low, medium, and high socioeconomic areas, as indexed by their postal codes from the Socio- Economic Indexes for Areas within Western Australia [28]. School enrolments ranged from 210 to 1200 students. Of the schools, four were government-funded, while one was privately funded. In Western Australia, children currently remain in government funded elementary schools from Grades 1 to 7 before going to secondary school in Grade 8. Privately funded children commence secondary school in Grade 7.

Procedure

Approval to conduct the research was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the administering institution and the State Education Department. Convenience sampling was used to select schools to invite into the study. Telephone contact was then made with the principals of schools to explain the purpose of the research and invite their school’s participation; letters with further information and confirmation of participation followed. Principals who agreed for their school to participate in the study (n= 5) identified a school liaison to assist with recruiting participants from grades 5 to 10 (ages 10 to 15 years). The school liaison chose a class and all students (excluding those with learning disabilities requiring a teacher assistant) within that class were invited to participate in the study. On return of the signed parent and child consent forms, arrangements were made with the school liaison to conduct interviews of a random selection of approximately seven students at each school.

Interview protocol

A semi structured interview schedule guided interviews with the participants. This was developed based on previous research methodologies and a review of the literature [16, 22,29]. Questions were framed to explore adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of feeling lonely, being alone, and what these terms meant to them. With evidence showing that friendships are closely linked to perceptions of loneliness [30], the interviews also incorporated questions about their friendships.

Prior to the interviews, pilot testing was undertaken with five youths (aged between 9 and 16 years) to check for question suitability and content appropriateness. The final interview protocol incorporated three broad sections: 1) friendships, 2) aloneness, and 3) loneliness. Section 1, friendships asked about friendships, groups of friends, movement between friends and friendship groups, the importance of friendships in their life, and activities in which they engaged with their friends. Prompts relating to friendships were carefully worded to minimise any potential negative impact upon individuals with no or few friendships. Section 2, aloneness asked about feelings when alone, how often they were alone, what they liked and did not like about being alone, and choosing to be alone. Section 3, loneliness incorporated questions about differences between being alone and lonely, experiences of loneliness, how often they felt lonely, strategies they used to alleviate feeling lonely, causes of loneliness, and identifying and helping others who appeared lonely.

Data collection

Prior to undertaking each interview, the aims of the research were explained to each participant, the confidentiality of their responses was assured, and they were reminded that their involvement was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. No participant chose to withdraw at any stage of the research. Each adolescent was also asked prior to the start of the interview for permission to audio record the session; all but two agreed. In these two cases, field notes were taken by the interviewer. Interviews were conducted in a quiet room at the respective schools during regular class times. Interviews started with general conversation to place participants at ease, and to facilitate the free flow of their responses by drawing out some initial information about their siblings and school experiences. The interview protocol, as described previously, was then used to gather information about students’ feelings of friendships, loneliness and aloneness. Prompts were used to elicit further information about specific experiences or feelings during the interviews. No time limit was placed on the interviews, and their length varied between 15 and 30 minutes.

Data analysis

Conventional content analysis [31] of verbatim interview transcripts was completed with the assistance of N-Vivo (Version 9) [32]. Inductive analysis incorporated constant comparative coding, thus forming conceptual categories, relationships, and theory. [33,34]. This occurred in a cyclical and continuous process of data reduction, data organization and interpretation [35].

Results

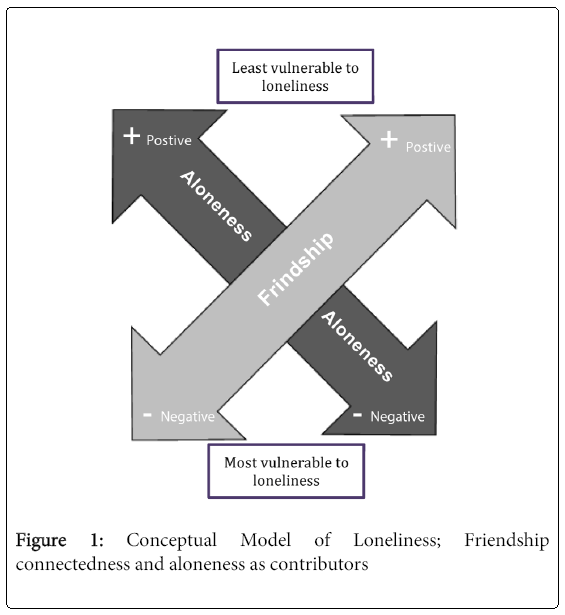

Loneliness was identified as a multifactorial experience which centred on two main constructs: 1) connectedness with friends, and 2) perception of aloneness. Qualitative insights support the concept of adolescents ‘positioned’ on continuums within these two constructs; 1) friendship- with connected and disconnected anchors, and 2) perception of aloneness – with positive and negative anchors. This conceptual model of loneliness is depicted in Figure 1. The following presentation and discussion of findings are framed around this model with illustrative quotes provided.

Friendships

Feelings of loneliness for adolescents appeared to be strongly related to their feelings of connectedness to friends at school. While the majority of the participants felt some level of connection to their peers, and considered themselves to have friendships of varying strengths at school, four adolescents in this study expressed strong feelings of disconnection and isolation from peers. For these adolescents it was clear that the absence of good school friends was very difficult and painful, as well as being associated with feelings of sadness. During interviews, it was also evident that a lack of friendships and the resulting loneliness had a negative ripple effect on the lives of these adolescents. The following quotes illustrate the contrasting impact of friendships:

Yes it is very important because I know that they are always there for me, whenever I need them. No matter what, you can talk to them, whenever you need them they are there.

(Female, Year 7)

...Um, I don’t know like every day, I’m not really happy ‘cause I don’t have the best life ‘cause of my friends at school, and so, I don’t know… I just kind of try to block it out. (Female, Year 9)

Some of the disconnection with peers coincided with periods of change, such as starting a new school, or friends leaving the school. One girl, whose best friend had left the school was worried that she would be in a ‘loner group’ if her other friends went to another school. One boy who had started at a new school a few months previously stated:

I’m alone every day at school….. Sometimes I just like try and stand with someone while they’re talking with a group, but I never really talk with them. (Male, Year 7)

Other participants who did not express current feelings of loneliness were able to articulate past experiences of loneliness and its emotional impact, or were able to identify others who appeared lonely and separated at school.

I remember when I moved I was sad, I was leaving my family and my friends behind, but now I’ve kind of got over it. (Male, Year 10)

I wanted her to play because she looked so sad and I didn’t like just ignoring her sitting there. But when she said no, I thought well there’s nothing I can really do I can’t drag her into my game if she doesn’t want to. (Female, Year 7)

Of the four adolescents indicating that they did not feel close or connected to anyone at school, three indicated they had no friends or had major problems with their friends at school. Of these, nearly all expressed a desire for more friends, closer friendships, and/or friends who understood them.

Yeah… I think I need more friends. Cause I don’t actually have that many friends. They sort of leave and stuff. (Female, Year 7)

Well I tried a few times but you know kids don’t like me, they just like kind of ignore me so, you know, I don’t really have any friends at this school yet. (Male, Year 7)

Participants were aware of the importance of friendships in their lives. When asked about the importance of friendships the majority of adolescents expressed strong or good connection to friends at school and/or outside of school and explained that their friends understood them, could be trusted and ‘stood by’ them. Being aware of the importance of feeling attached or connected, these adolescents described how they perceive their friendships:

Yes they [friends] are very important because I know that they are always there for me whenever I need them. No matter what, you can talk to them; whenever you need them, they are there. (Female, Year 7)

I can tell many things to my friends which I cannot tell anyone else; whenever I want, whatever I want and they understand me. (Female, Year 7)

The analysis highlighted that friendships and social connections were important for emotional wellbeing, as well as the supportive role social friendships play in preventing feelings of loneliness. During the interviews, a wide range of characteristics of good friends emerged. Being similar, understanding, and trust came through most strongly as important for good friendships.

Yes, I do because we have fun together and we spend a whole lot of time together. My friends understand me, and I understand them. (Male, Year 6)

Well they help you get along at school and if you have a problem then you can go to them, and they can help you out. (Male, Year 10)

Like we share secrets and like we’ve been hanging out for like two years for now so, like, it’s really close between us. (Male, Year 7)

Aloneness

Whilst many of the participants were able to describe positives of being alone, they also raised negative feelings associated with being alone. Perceptions of aloneness also appeared to be situational. For instance, being alone at school was considered problematic and associated with ostracism, discomfort or sadness, whilst being alone at home was much more accepted by the adolescents.

Participants identified many positives related to spending time alone including: recharge, relax and have peace; provide space; give freedom to choose their own activities and; have ‘time’.

It could mean that you want to be alone if you’re having some problems and you feel like being alone or having your own space, that can be the case. Like, you want to be, you’re on your own sitting down just thinking things and you know, you, you want some space from everything. (Female, Year 6)

It’s good to have friends and everything but sometimes you just need your personal space. (Male, Year 7)

Well most of the time when I’m alone, by myself, it’s just because I, I want to be like that. Just sitting at home relaxing. (Male, Year 8)

For some, being alone was considered purposeful and used as a strategy to deal with frustrations or issues arising with family or friends. Participants also explained the positive impact created from spending alone.

When I have a fight with my friends, I want my space. (Female, Year 5)

It’s quiet and sometimes you need to be alone to calm down from something and so you’re by yourself, you’re quiet, you can calm down if you’re frustrated at something. (Female, Year 5)

Whilst being alone as an occasional occurrence was generally accepted and expected by the adolescents, some of the students (particularly those in primary school) struggled to find positive aspects or benefits associated with being alone. Further, when asked the reason they spent time alone the vast majority of reasons provided by the primary school, and some of the secondary school students, were negative. These included being angry or upset; having an argument or issues with friends or a family member; being bullied; not wanting to talk; being different to or not getting along with others; and that nobody cares or nobody was home.

Well, sometimes it helps you. Like if you’re a bit angry, it’s good to be alone and think over something. Instead of acting quickly, or something like that. (Male, Year 7)

..yes, yes when I have person problems I prefer to be by myself. (Male, Year 6)

Some participants expressing a negative attitude to aloneness also had problems with their friendships or felt lonely at school. When asked if there was anything good about being alone one male who had no friends at his new school responded:

Probably not, there are no advantages in it. (Male, Year 7)

Another adolescent who had a negative attitude to aloneness and friendship problems had difficulty adjusting when left alone:

Lonely- friends walk off - can’t find them, feel like just been left, feel left out, feel sad that friend doesn’t want to be around me. (Female, Year 9)

Two girls reported difficulties in identifying positives of being alone but had previously reported strong friendships during the interview. When asked how they felt about being by themselves their responses were:

Sad and unhappy. (Female, Year 6)

I don’t like being by myself’….lonely and you’re by yourself, there’s not much you can do. I hate being bored. (Female, Year 6)

The setting in which one was alone appeared to be an important determinant of how the adolescents interpreted being alone. For example, spending time alone at home was discussed quite differently from being alone at school. There was a sense that in the school setting being alone was to be avoided at all costs; students who experienced being alone at school were not happy with the situation, and those observed to be alone were considered lonely, ‘loners’, or ostracised in some way.

I try to not be alone, but in the end… I can’t really talk to anyone, cause I can’t, they [other students] sort of like spread out over the place and they are always doing stuff.

(Male, Year 7)

Sometimes kids can be a bit mean and … say ‘you’re a loner’. (Female, year 5)

There’s a new kid in my class… he seems lonely…. because he’s upset, he’s got nothing to do, he’s got no one to play with. (Male, Year 8)

We do not have many students in school who seem very lonely. Usually some are sitting the corner looking down, looking very sorry for themselves and very low. They don’t look good at all. (Female, Year 7)

In general, participants reported they would never or very rarely intentionally choose to be alone at school. Choosing to be alone at school would usually be related to arguing or being upset with friends.

…maybe when I’m having like, some problems at school and like I just want to be by myself and away from everyone and I just feel like maybe if I just, get some space I can maybe just come back and we can try and sort things out. (Female, Year 6)

Being alone at home was considered normal and acceptable by most, and this was particularly evident for the older participants. However, for some participants even being alone at home was perceived to be undesirable. This was more evident for the children who appeared to not yet have developed the desire to spend time alone, for example one girl’s response when asked if she ever wanted to on her own responded;

..nah not really. I don’t like being by myself. (Female, Year 7)

Negative feelings about being alone at home also appeared to be related to frequency of involuntary aloneness (e.g., parents at work, no siblings at home, or not being allowed to socialise with friends). Specifically, those adolescents who were regularly at home alone appeared to have a more negative attitude to aloneness. Examples of responses to the query about if they spent much time alone:

Well, um, sometimes like when I’m alone, I don’t like it cause I have too much of my own company and it gets a bit frustrating, but I think if you’re really, really lonely all the time, you don’t have friends, you get a bit upset about it- but sometimes you need that space for yourself. (Female, Year 7)

Yeah, and during the holidays. As well my mum and dad are full time [working] parents so I guess I spend a lot of time in my own company [expressed sadness]. (Female, Year 7)

Although many participants could identify differences between loneliness and being alone, those who expressed friendship issues found it more difficult to distinguish between the two, or to define each experience separately. For a few, loneliness and being alone was seen as ‘the same’. Some participants also expressed experiencing negative emotions such as feeling depressed or bad when they were alone. For example,

..[I] was really, really alone and I was really emotional and stuff… and I felt really bad and I cried... (Female, Year 8)

When you’re all by yourself and you’re scared, well not necessarily scared but there’s no one around you. (Female, Year 6)

Sometimes it can be a good thing or a bad thing. Because when you spend too much with yourself it leads into depression for me and sometimes it’s a good thing for you to think about yourself. Because what I do, when I’m at home and I’m just fed up with my parents and I always see them I just get up my keys and then open the door to my room and I just sit there. And then stare to the black space (laughs). (Female, Year 7)

Discussion

This study highlights that loneliness is multidimensional and is influenced both by the existence (or not) of meaningful friendships as well as by how adolescents frame and experience being alone. Further, being alone can have both positive and negative associations for adolescents, and this appears to be influenced by the setting and frequency of being alone. Aloneness can be buffered by friendship networks, and experienced more negatively where friendships and social connectedness are lacking. This epitomises vulnerabilities associated with unstable friendships; friends are the domain in which adolescents pursue the imperative of social connection [36]. In this current study it was evident that feeling disconnected to peers and perceiving a lack of friendships in the school setting was particularly difficult for adolescents. This may be due to the public nature of friendships in the school setting; those with no or few friends are acutely aware of the potential negative reputation elicited from being alone at school (further compounding negative emotions associated with feeling disconnected). Young people experiencing both a lack of connection with friends and negative aloneness seem to be at particular risk of poorer mental wellbeing.

The findings underscore the important role of friendships during adolescence, an unsurprising finding given friendships are significantly associated with adolescent wellbeing [37], and are a preventive factor against problematic outcomes in adolescence [38]. Conversely, detachment from friends is considered a risk factor for dysfunctional adjustment [39] and depression [40]. Of particular note in the present study, was that although a minority of children and adolescents were identified as experiencing feelings of disconnection themselves, many participants were able to identify peers who had few or no friends. These “lonely” individuals were perceived as “sad”, “loners” and/or “lonely”. The impact of ongoing school friendship problems on the experience of loneliness for adolescents is evident. The potential effect of these feelings upon future mental wellbeing is considerable. This is particularly an issue in the secondary school sector where arguments, ostracising, feeling disconnected from others, and reputations (such as being a ‘loner’) are more enduring than in primary school.

Whilst adolescent friendship issues contribute to feeling lonely, these findings support the premise identified previously that positive aloneness (also known as solitude) is also an important factor within the construct of loneliness [23,24]. Understanding and making the most of periods of time alone assists learning and thinking, and a positive attitude to aloneness facilitates healthy emotional development during childhood and adolescence [41]. Adolescents often seek time alone to reflect and relax, develop the self, and to deal with emotional tensions and this is considered a reflection of emotional maturation [42]. Coinciding with findings from our previous research [24], the older adolescents in the current study were also more likely to report positively on time they spent alone. Whilst positive aspects of aloneness were expressed by a large proportion of the adolescents, some participants reported negative attitudes to time alone. According to Heinrich and Gullone [4], adolescents who have a negative attitude towards aloneness can develop negative views about themselves, see others as less trustworthy and supportive, and feel powerless to change their ‘isolated’ predicament. Such feelings place young people at risk of adverse physical, psychological, social, and mental health outcomes [9,43-45]. These can include depression [6]; eating disturbances, obesity and sleep disturbances [8]; and adolescent alcohol use, general health problems, less than optimal well-being or somatic complaints [9]. For some young people, spending time alone is a particularly negative experience, seemingly because it provides them with the time to ruminate, in many cases about things which are negative and anxiety provoking. Clark and Beck [46] highlighted that dysfunctional thinking patterns may contribute to anxiety pathology; therefore, strategies which prevent the development of negative attitudes to aloneness are likely to be beneficial for the future mental health of young people.

Our qualitative study findings are important because they provide implications and direction for health practitioners, educators, and health promoters in developing targeted strategies and approaches to prevent and reduce loneliness. Targeted therapy, for example, in which cognitive mediational strategies guide behaviour [47], may assist adolescents who are disconnected, struggling to engage in supportive friendships and peer-groups, or experiencing negative aloneness. Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) has been used previously in schools to treat and prevent loneliness [48]. The results also highlight the impact of being alone at school when others are in groups, reinforcing the need for schools to consider strategies to counter this. A number of promising examples of school initiatives engaging young people in reducing the number of adolescents alone during breaks was identified in the study schools. In one primary school a mentoring program in which older year groups supported younger children was considered helpful by the study participants (who were mentors). Another program incorporating sport faction/group activities held at lunch time supported newer students at a secondary school; unfortunately, it was only held in first term and the strategy did not seem to be of sufficient length to establish good friendships for some of the adolescents.

These research results also have implications for policy. Recent calls for ‘health in all policies’ [49] highlight the need to address issues related to the mental health of adolescents at all ‘service’ levels, such as government bodies, schools and classrooms themselves. Family friendly work place policies that support and indeed encourage parents to work flexible hours, part time or work from home to reduce the total time their children spend at home alone are relevant. There are also implications for policies that may indirectly impact upon time children and adolescents are alone and considered approach to policymaking or changes can prevent unintended consequences. For example, policies such as reducing or removing government financial assistance for sole parents could inadvertently increase the time children and adolescents spend at home alone; this is particularly applicable when considering existing constraints and issues (e.g. high child-care costs and limited places, inappropriateness of child-care for mid-older adolescents, school holidays versus parent annual holiday entitlements). At a more local level, Qualter [48], in her commentary of the role of schools in adolescent mental health, asserts the importance of a whole school approach in treating and preventing adolescent loneliness. These recommendations include addressing policies and practices within schools such as desk placement, recess and lunch activities, and actions that result in student exclusion. She also advocates for individual targeted therapy and programs. Schools, rather than being a setting for vulnerability and stress for some, can be instead a setting promoting mental health. Indeed, schools can support the development of positive social skills, relationships and the self, as well as providing opportunity for the enhancement of one’s social self [48].

Prior to concluding, it must be acknowledged that the sample for this study comprised a relatively small number of adolescents from conveniently sampled schools. Further, the majority of the sample were in the ‘early-adolescence’ age category. Whilst attempts were made to recruit older adolescents into the study, submission of parental signed consent forms for the mid-older age groups was scant; school staff reported this as being typical of the older students. Future studies could consider incentives or rewards to encourage participation. Only a small proportion of the participants were experiencing enduring loneliness; this may be due to the reluctance of lonely adolescents to participate in such a study. We did not explore the potential buffering of loneliness created by strong family connections and relationships. Further, it is acknowledged that the authors’ subjectivity may have guided development of interview questions and probing during interviews; to reduce subjectivity we incorporated the following strategies; interview questions and probing questions developed and reviewed by all five authors, interviews were conducted by two authors, consultation and cross-checking during data analysis by two authors and confirming proposed and final categories by all authors.

The findings from the present study highlight the multidimensional nature of loneliness and indicate that a range of approaches would assist with addressing loneliness in young people. Schools are an ideal setting for early intervention [48,50], particularly due to the vulnerability associated with being alone while at school and the impact of school friends and peer relationships. School programs may not only assist with preventing the development of feelings of disconnection from friends and a negative attitude to aloneness, but also in facilitating friendship development and engendering a positive attitude to aloneness. Far-reaching benefits are likely to be achieved by the implementation of strategies combined with cultural shifts within schools which aim to foster and strengthen students’ empathy towards those more vulnerable peers. This may also include education about identifying those who may be lonely and mechanisms by which students can help each other.

Conclusion

Loneliness is associated with a multitude of adverse physical, psychological, social and mental health outcomes and can become a debilitating condition, particularly if not resolved prior to moving out of adolescence. The present findings show that adolescents differentially experience feelings of loneliness along the dimensions of friendships and aloneness. As the school is a setting in which adolescents are especially vulnerable to feelings of loneliness, schoolbased interventions could be particularly useful as well as widereaching. Assisting adolescents to both develop secure friendships and positive attitudes towards aloneness has an important role to play in reducing adolescent loneliness as well as decreasing the risk of associated negative outcomes.

References

- Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC (2009) Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues ClinNeurosci 11: 7-20.

- Pelkonen M, Marttunen M (2003) Child and adolescent suicide: epidemiology, risk factors, and approaches to prevention. Paediatr Drugs 5: 243-265.

- Wasserman D, Cheng Q, Jiang GX (2005) Global suicide rates among young people aged 15-19. World Psychiatry 4: 114-120.

- Heinrich LM, Gullone E (2006) The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. ClinPsychol Rev 26: 695-718.

- Gallagher M, Prinstein MJ, Simon V, Spirito A (2014) Social anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation in a clinical sample of early adolescents: Examining loneliness and social support as longitudinal mediators. J Abnorm Child Psychol:42:87 1-883.

- McWhirter BT, Besett-Alesch TM, Horibata J, Gat I (2002) Loneliness in high risk adolescents: The role of coping, self-esteem, and empathy. Journal of Youth Studies 5: 69-84.

- Yang B,Clum GA (1994) Life stress, social support, and problem solving skills predictive of depressive symptoms, hopelessness, and suicide ideation in an Asian student population: A test of a model. Suicide Life Threat Behav24: 127-139.

- Cacioppo JT, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, McClintock MK, Malarkey, et.al., (2000) Lonely traits and concomitant physiological processes: The MacArthur social neuroscience studies. Int J Psychophysiol35: 143-154.

- Krause-Parello CA (2008) Loneliness in the school setting. J SchNurs 24: 66-70.

- World Health Organization (2005) Child and adolescent mental health policies and plans. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Brennan TP, Perlman D (1982) Loneliness at adolescence. In Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Wiley New York

- VanderWeele TJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT (2011) A marginal structural model analysis for loneliness: implications for intervention trials and clinical practice. J Consult ClinPsychol 79: 225-235.

- Erikson EH (1994) Identity: Youth and crisis. WW Norton & Company.

- Chipuer HM, Pretty GH (2000) Facets of adolescents’ loneliness: A study of rural and urban Australian youth. Australian Psychologist 35: 233-237.

- Miller DN, Jome LM (2010) School psychologists and the secret illness: Perceived knowledge, role preferences, and training needs regarding the prevention and treatment of internalizing disorders. School Psychology International 31: 509-520.

- Asher SR, Paquette JA (2003) Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science 12: 75.

- Galanaki E, Polychronopoulou S, Babalis T (2008) Loneliness and social dissatisfaction among behaviourally at-risk children. School Psychology International 29: 214-229.

- Neto F, Barros J (2000) Psychosocial concomitants of loneliness among students of Cape Verde and Portugal. J Psychol 134: 503-514.

- Asher SR, Wheeler VA (1985) Children's loneliness: a comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. J Consult ClinPsychol 53: 500-505.

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE (1980) The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J PersSocPsychol 39: 472-480.

- Russell DW (1996) UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess 66: 20-40.

- Weiss RS (1973) Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Goossens L, Lasgaard M, Luyckx K, Vanhalst J, Mathias S, et al. (2009) Loneliness and solitude in adolescence: A confirmatory factor analysis of alternative models. Personality and Individual Differences 47: 890-894.

- Houghton S, Hattie J, Wood L, Carroll A, Martin K, et al. (2014) Conceptualising Loneliness in Adolescents: Development and Validation of a Self-report Instrument. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45: 604-616.

- Perlesz A, Lindsay J (2003) Methodological triangulation in researching families: making sense of dissonant data. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 6: 25-40.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J (2003) Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage.

- Patton M (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage Publications Inc, California.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2003) Census of population and housing: Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA). Australia, Canberra.

- Parker JG, Seal J (1996) Forming, losing, renewing, and replacing friendships: Applying temporal parameters to the assessment of children's friendship experiences. Child Development 67: 2248-2268.

- Parker JG, Asher SR (1993) Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology 29: 611-621.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15: 1277-1288.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2011) NVivo qualitative data analysis software.

- Patton MQ (1990) Qualitative evaluation and research methods. SAGE Publications, inc.

- Merriam SB (1988) Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass.

- Sarantakos S (1993) Social research. Macmillan South Melbourne.

- Larson RW (1999) The uses of loneliness in adolescence. In Rotenberg K, Hymel S eds Loneliness in Childhood and Adolescence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Greenberg MT, Siegel JM, Leitch CJ (1983) The nature and importance of attachment relationships to parents and peers during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 12: 373-386.

- Tambelli R, Laghi F, Odorisio F, Notari V (2012) Attachment relationships and internalizing and externalizing problems among Italian adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review 34: 1465-1471.

- Cicchetti D,Cummings M, Greenberg MT, (1993) Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: 4-49.

- Kobak RR, Sudler N, Gamble W (1991) Attachment and depressive symptoms during adolescence: A developmental pathways analysis. Development and Psychopathology 3: 461-474.

- Buchholz ES, Chinlund C (1994) En route to a harmony of being: Viewing aloneness as a need in development and child analytic work. Psychoanalytic Psychology; Psychoanalytic Psychology 11: 357-374.

- Galanaki E (2004) Are children able to distinguish among the concepts of aloneness, loneliness, and solitude? International Journal of Behavioral Development 28: 435-443.

- Cramer KM, Barry JE (1999) Conceptualizations and measures of loneliness: a comparison of subscales. Personality and Individual Differences 27: 491-502.

- Doman LC, Roux A (2010) The causes of loneliness and the factors that contribute towards it: A literature review. TydskrifVirGeesteswetenskappe. The Journal of Humanities 50: 216-228.

- Lasgaard M, Goossens L, Elklit A (2011) Loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and suicide ideation in adolescence: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. J Abnorm Child Psychol 39: 137-150.

- Clark DA, Beck AT (2010) Cognitive theory and therapy of anxiety and depression: convergence with neurobiological findings. Trends CognSci 14: 418-424.

- Durlak JA, Fuhrman T, Lampman C (1991) Effectiveness of cognitive-behavior therapy for maladapting children: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 110: 204-214.

- Qualter P (2003) Loneliness in children and adolescents: What do schools and teachers need to know and how can they help? Pastoral Care in Education 21: 10-18.

- World Health Organization (2013) The Helsinki Statement on Health in All Policies. Proceedings of the Conference Name.

- Burns J BS, Glover S, Graetz B, Kay D, Patton G, et al. (2008) Preventing depression in young people: what does the evidence tell us and how can we use it to inform school-based mental health initiatives? Advances in School Mental Health Promotion 1: 5-16.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 18398

- [From(publication date):

December-2014 - Apr 07, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 13606

- PDF downloads : 4792