How Social Constructs and Cultural Practices Erect Barriers to Facility Deliveries in Rural Nigeria: A Review of the Literature

Received: 04-Mar-2019 / Accepted Date: 24-Apr-2019 / Published Date: 01-May-2019

Abstract

Nigeria has the world’s second highest maternal mortality burden. The latest national demographic and health survey put the figures at 576 per 100000. The proximal reasons for this burden are: Hemorrhage, sepsis, obstructed labor and unsafe abortion related complications. Within the last 16 years (circa 2000), with the intervention of the millennium development goals initiative and a return of democratic government to Nigeria, a new regime of advocacy and good governance demand has brightened the spotlight on poor health indicators in general and maternal and child health in particular, in turn making maternal and child issues, high health priorities. Political will has aligned with resources and configured a more robust response to the maternal morbidity and mortality crisis. Improvements have been noted in the South of Nigeria, however in the North, progress is slower and change more jaded. The social and cultural texture of this region plays a distal role in the slow progress noted. More research needs to be undertaken to better understand the role of power gradients, religious beliefs and conditioning, social perceptions and pressure, educational status and transgenerational cultural practices. This systematic review examines the state of knowledge and the extent of gaps.

Keywords: Maternal mortality; Nigeria; Social status; Religious beliefs; Cultural practices

Introduction

Nigeria’s population is 2% of the world’s total population, but Nigeria carries 10% of the global maternal mortality burden [1]. In the last 16 years, a combination of Millennium Development Goal 5 and the return of democratic governance in Nigeria has focused a stronger spotlight on the crisis [2,3]. Nigeria did not meet MDG targets (reducing the incidence of maternal deaths by 75% by 2015) [4]. The proximal causes of morbidity/mortality in Nigeria are clinical factors viz: Hemorrhage, sepsis, obstructed labor and complications from unsafe abortions. These factors indicate a systemic weakness in the quality and availability of services. This paradigm has often informed program design. However, recent studies suggest the problem is more complex and thus requires more contextual nuance. Extra clinical factors such as-distance to facility and cost of transportation, decision making power and spiritual and cultural conditioning vis a vis health seeking behavior have all been shown to play a significant role in forming barriers or acting as enablers to better outcomes for maternal morbidity and by extension mortality [3-5]. Furthermore, social attitudes towards extra-marital pregnancy and subsequent unsafe abortion practices play a highly significant role. This problem is largely a “Northern Nigeria problem”, this region has a much higher burden that the rest of the country, 165/100000 in the South and as much as 1549 in the North [1]. The North of Nigeria is largely disadvantaged with low literacy, poor sanitation, low urbanization and high birth rates [6]. This environment has bred gender related disadvantages and insular social conditioning.

In more recent times (circa 2000), maternal and child health intervention have been scaled. Multilateral donors and local governments have collectively programmed more resources into removing distance and financial barriers. Bringing efficacious initiatives closer to the epicenters. As such skilled birth services and professional support for pregnancy and delivery management have been brought closer to the place of greatest need and highest impact. Nonetheless, the interventions appear not be showing optimal results. Nigeria has not met any of its maternal morbidity/mortality targets.

There are gaps in knowledge that need to be plugged. What is available in terms of research with regards the Nigerian mortality and maternal situation, does it adequately describe the sociology of the phenomenon? How should this be countenanced and what logical conclusions will be valid? This literature review is undertaken with a view to answering these questions.

Methodology

Data search

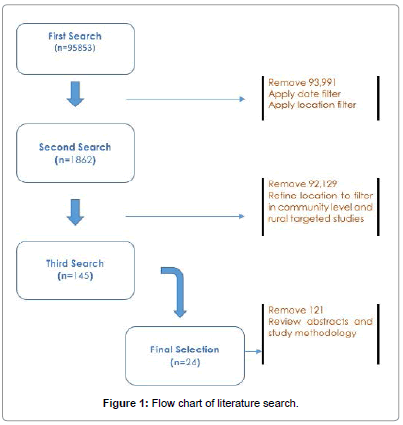

A systematic review of databases and grey literature has been undertaken. As an initial step, keywords and searchable terms were framed out using a modified PICO, modified into PPO-Population Phenomena Outcomes. Phrases formulated where: Maternal mortality, rural Nigeria, social status, religious beliefs, cultural and traditional practices. These keywords were fed in string combinations i.e., (First Search, Mortality+Rural Nigeria+Social status, Second Search: Maternal Mortality+Rural Nigeria+Religious Belief, Third Search: Maternal Mortality+Rural Nigeria+Cultural and traditional Practices), into Web of Science, University of Portsmouth’s discovery platform, PubMed, World Health Organization’s research resource: Hinari and the Cochrane library. Searches applied a 10 year cut off i.e., a filter was applied to exclude studies conducted earlier than 2006, this was in order to review contextually relevant studies for which findings were still applicable. Furthermore, searches targeted studies that applied a wholly qualitative or partially qualitative methodology as the review was interested in incorporating the texture of opinions and nuances of conditioning which will be palpable in cultural idiosyncrasies. Initial searches where done mostly on online databases. However, due to the strict time window with regards the inclusion criteria and the subsequent narrowing of the selection filter, a search for grey literaturemainly through the snowballing technique i.e., reviewing reference lists and perusing domain specific journals was conducted separately. Furthermore, field experts were contacted and conference notes are reviewed. A search flowchart is included in Figure 1.

Criteria are listed here:

A. Inclusion criteria

1. Only original studies have been reviewed. And these studies are studies in which the central question was on maternal health in Nigeria primarily or similar settings in which the sociodemographic dynamic is similar.

2. Original studies undertaken not later than 2006. In order to have a review of presently relevant facts.

3. All studies in which a wholly qualitative or partially qualitative methodology was deployed.

B. Exclusion criteria

1. Studies conducted before 2006.

2. Reviews of studies conducted.

3. Studies not set in Nigeria or similar environments.

Review and analysis

Collated papers have been read individually, simultaneously sifting and filtering for key words and phrases. Phrases emerging repeatedly (across papers) have been used as central themes. Key words emerging across papers have been used as sub-themes. By so doing the papers has shown a delineation with which it is possible to identify two categories of factors i.e., health system related factors and non-health system related factors. These categories have been reviewed and are presented herewith. Presentation of both of these categories is done to determine the linkages between health systems centric issues and the broader non-systemic issues which are more social and demographic in nature. And gauge the interaction Figure 1: Flow chart of literature search. between these dynamics (Table 1).

| Authors | Title of Study and Period | Methodology | Findings and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fagbamigbe and Idemudia [13] | Barriers to antenatal care use in Nigeria: Evidences from non-users and implications for maternal health programming, 2015 | Secondary data review of the national HIV/AIDS and reproductive health Survey-using bivariate analyses of relationships between characteristics and reasons given for taking ANC services. | Non-Use of ANC in commonest among poor, rural and currently married, less educated respondents from Northern Nigeria, especially from North Eastern Zone. |

| Adewemimo et al. [9] | Utilisation of skilled birth attendance in Northern Nigeria: A cross-sectional survey, 2014 | Cross-Sectional Analysis-set in Funtua, Katsina State, North West Nigeria. | Enabling factors for skilled birth attendance include; husband’s approval, affordability of services and availability of staff at health facilities. |

| Crowe et al. [15] | How many births in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia will not be attended by a skilled birth attendant between 2011 and 2015?, 2012 | Trend analysis of secondary data | Millions of women within South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa will give birth without an SBA. Efforts to improve access to skilled attendance should be accompanied by interventions to improve the safety of non-attended deliveries. |

| Erim et al. [5] | Assessing health and economic outcomes of interventions to reduce pregnancy-related mortality in Nigeria | Data synthesis of secondary data using computer models built around related indicators | “Principal findings are that early intensive efforts to improve family planning, accompanied by a systematic stepwise scale-up of intrapartum and emergency obstetric care, could reduce maternal deaths by 75%” |

| Tukur et al. [11] | Why women are averse to facility delivery in northwest Nigeria: A qualitative inquiry, 2013 | Qualitative methods, key informant interviews and focus group discussions. | “The common reasons for aversion to facility delivery include poverty, cost of service, non-permission from husband, alien and negative attitude of staff. Other reasons include its unnecessary, lack of privacy and exposure to non-relatives and men and dislike/distaste for being touched by male other than their husband and lack of empathy” |

| Ijadunola et al. [7] | New paradigm old thinking: The case for emergency obstetric care in the prevention of maternal mortality in Nigeria | Mixed methods, descriptive analysis using survey data collection techniques, semi-structured questionnaires. | Low capacity for emergency obstetrics care affects quality of care and leads to trust and perception issues. |

| Olusanya et al. [3] | Non uptake of facility based maternity services in an inner-city community in Lagos, Nigeria: An observational study. | Quantitative-structured questionnaires administered by testers. | “Scaling-up of skilled attendants and facility-based services is necessary for improving maternal and child care in developing countries but their effectiveness is crucially influenced by the uptake of such services”. |

| Susan et al. [4] | Reducing rural maternal mortality and the equity gap in northern Nigeria: The public health evidence for the community communication emergency referral strategy | Case study | Community based emergency obstetrics care, when integrated into the public health systems provides an equitable vehicle with poor rural women can receive delivery care. |

Table 1: A selection of core reviewed literature.

Health system related factors

Capacity gaps at health centers: The lack of adequately skilled manpower to respond to emergencies during delivery and prevent escalation is a considerable barrier to health facility deliveries. This entrenches a culture of doubt in conventional medicine and institutes a system of “self-help” Studies show that job based training and retraining is rare and as such most emergency obstetric care workers do not possess baseline skills [7]. Furthermore, the urban-rural dichotomy in Nigeria is a known problem and has led to a politicization of health worker postings and by extension a disproportionate dearth of capacity at rural health centers, which is the default recourse for most disadvantaged women [8].

Poor facilities at health centers: Related to the weak professional capacity within the health facility is the absence of resources at the health facility [9]. Going by the United Nations Population Fund’s framework for Emergency Obstetric Care, only 6% of surveyed facilities provide the suite of services that qualify a facility as a functional Emergency Obstetrics Care Center (EOCC) i.e., the satisfying the “signal” functions, (parenteral antibiotics, oxytocics, anticonvulsants, neonatal resuscitation, assisted vaginal delivery, manual removal of the placenta and removal of retained products) [10]. Where interventions are known to be operational, oversubscription and corruption undermine improved outcomes. Complaints range from women being forced to deliver on the floor, to not receiving basic medication and the generally poor state of facilities.

Distance/cost of transportation: The associated costs of reaching the facility. The significant cost of transporting an emergency to a health center is a powerful constituent of one of the 3 traditional delays that often prove fatal (the delay to get help). Whilst casual association cannot be gauged, some reviewed papers using mixed methods showed that as many as 25% of respondents sighted distance/cost of transportation as a barrier, find a smaller but nonetheless significant 6.8% [9,11]. Whilst other papers do not specify numbers, several have vivid discussions concerning the barrier of transportation [12].

Intimidation/maltreatment at health centre: This is a cross cutting issue, as it also appears to be a non-health sector issue that is related to social status and financial power. Studies show a poor and unprofessional attitude from health workers “they treat us as villagers”- (comments from a focused group discussion) [12]. Another study recorded responses such as “unfair treatment from health workers”, Ajayi et al., speak about Unprofessional practices, attitudes and behaviour by health workers. Specifically, unprofessional practice encompassing a lack of empathy, coarseness in language, a disregard for traditional and cultural concerns and using freely provided resources for illicit profits.

Non-health system related factors

The primary cause of maternal mortality is a weak health system. However, what is also apparent is the fact social factors undermine the optimization of health system strengthening benefits. Emerging themes show that, beliefs and traditions are powerful conditioners. For each systemic failure there is a corresponding social link. These links are reviewed herewith.

The low status of women: Studies have found that the role of women in Nigerian society is a disadvantaged secondary one. Power gradients are particularly steep in the North, where the setting is more rural and paternalistic. These precepts were a strong theme occurring in this literature review, a common notion is, “husbands/spouses or guardians’ wield the power of final decisions [4,13]. The dependent position of women in Nigerian society in general and in the North in particular has a direct bearing on health seeking behaviour. Enabudoso and Igbarumah talk about autonomy of choice as a key consideration in electing for life saving caesarean section. Another study found that 25% of women sight husband’s permission as an enabler for the utilisation of skilled birth attendants [9]. Existing studies also speak about the “lowstatus” of women in Northern Nigeria particularly as a contributor to maternal mortality [8]. These low statuses inhibit choice with regards reproductive age, parity and take up of services.

Religious beliefs: The Nigerian crisis has a northern dimension, the north of Nigeria is predominantly Muslim, where the concept of Dhu-Haram is practiced. A Dhu-haram is a male counterpart (usually a husband or relative). The Dhu-Haram principle has given rise to the concept of “Kunya” loosely translated to mean modesty. A woman is supposed to be modest particularly in relation to inter-gender interactions. Because of historical gender biases-not enough female health workers exist. The “Kunya” concept imbibes a culture of minimal inter-gender contact, which affects attendance at facilities that are often male operated.

Transgenerational traditional practices: Several studies find that birth at home has been “normalised”, a common reason for not taking up of clinical services was given as not necessary or not commonly practiced. The practice of taking herbs and local concoctions during pregnancy is passed down from generation to generation and has become entrenched. Rural mothers who did not use clinical services have passed the behaviour to their children by indoctrination. Adewemimo et al, speak about home birth as more culturally acceptable, Furthermore, link delays in seeking care for emergencies such as eclampsia to traditional beliefs about eclampsia “pregnant women affected by eclamptic fits or seizures are believed to be possessed by evil spirits” for which “local, more meta-physical” remedies are sought [8]. Olusanya et al. explain that use of local herbs in pregnancy is very wide spread, reporting that almost 40% of women use herbal medicine [3]. Lawoyin et al. speak about the concept of the African world view, in which accidents such as maternal deaths do not just happen but are divinely orchestrated [2].

Abortion legislation: Nigeria has a low contraceptive use rate and consequently a high pregnancy rate. Extra-marital pregnancy is stigmatized and children born out of wedlock are often ostracized. Abortion is officially illegal-allowing it only when a woman’s life is in danger, this has driven abortions underground and by extension made them dangerous. This is why 20% of global estimates of abortion related deaths happen in Nigeria [1]. Because of the public health implications for Nigeria, there is a lobby to change abortion legislation. Lawoyin et al., speak about responses from focused group discussions in which participants examine the role of abortion legislation and the part it plays in stigmatizing and shaming the practice. Changing legislation might be far-fetched as this is not on the political agenda. However, the public health community will need to use it as an entry point for debate and discussion about safe sex and contraception.

Discussion

This review provides an x-ray of the state of knowledge with regards the health effects of religious beliefs, social norms and traditional practice. The direct cause of poor maternal outcomes is a weak health system [8]. Programming in the last decade has conducted a health systems strengthening approach, responding to capacity and resource gaps within the health facility and strengthening availability of skilled birth attendance. However, the utilization of these newly available services is not optimal, associated costs, mainly transport related remain a barrier, long existing confidence issues still linger [5]. Directly, related to these are religious beliefs particularly regarding inter-gender relationships, decision making power in relation to health seeking behavior, spirituality as a coping mechanism and unsafe abortions [14,15]. The health system related factors are better understood and easier to measure than the non-health factors. More research is needed to understand the roles of social conditioners, physiological anchors and the level of internalization of traditional practices. This will be necessary to optimize the response and meet new program goals and targets.

Conclusion

Do social constructs and trado-cultural practices erect barriers to facility deliveries? The epistemology surrounding this notion has been well studied but we are still no better at understanding them. Weak systems often exist because of weak demand. Weak demand is sometimes a result of poverty and or suppression of free will. Finally, generations of solution seeking behavior have developed alternatives that have become entrenched and hard to disengage. Further enquiry is needed as a first step and greater integration of traditional and cultural nuance in programme planning is urgent.

Review Limitations

This paper is written as a literature review, as such it is limited in the scope of its underlying nature. It relies exclusively on secondary data and will inherit whatever bias has been incorporated in the original study. This is in addition to the author’s “confirmation bias” which is known to make a researcher look for data that conforms to personally entrenched views.

Furthermore, as is evident in the number of reviewed papers, there is a general dearth of studies that examine the sociology of choice with regard to pregnancy and place of delivery in rural Nigeria. Whilst this is the case, this review could have benefited from a broader scope of search. Maternal morbidity and mortality in Nigeria is a global public health concern and has been studied extensively, more publications are expected but a good quantum probably exists as grey literature.

Declarations

Disclosure

Author reports no conflict of interest or financial motivation.

Acknowledgments

The author will like to acknowledge colleagues on the Professional Doctorate in Health Sciences and faculty at the University of Portsmouth for their support.

References

- Kale O, Erinosho O, Ojo K, Owudiegwu U, Esimai O (2006) Nigerian health review. Health Reform Foundation.

- Lawoyin TO, Lawoyin OO, Adewole DA (2007) Men’s perception of maternal mortality in Nigeria. J Public Health Policy 28: 299-318.

- Olusanya BO, Alakija OP, Inem VA (2010) Non-uptake of facility based maternity services in an inner-city community in Lagos, Nigeria: An observational study. J Biosoc Sci 42: 341-358.

- Aradeon SB, Doctor HV (2016) Reducing rural maternal mortality and the equity gap in northern Nigeria: The public health evidence for the community communication emergency referral strategy. Int J Womens Health 8: 77-92.

- Erim DO, Resch SC, Goldie SJ (2012) Assessing health and economic outcomes of interventions to reduce pregnancy-related mortality in Nigeria, BMC Public Health 12: 786.

- Antai D, Moradi T (2010) Urban area disadvantage and under-5 mortality in Nigeria: The effect of rapid urbanization. Environ Health Perspect 118: 877-883.

- Ijadunola KT, Ijadunola MY, Esimai OA, Abiona TC (2010) New paradigm old thinking: The case for emergency obstetric care in the prevention of maternal mortality in Nigeria. BMC Women’s Health 10: 6.

- Vogel JP, Bohren MA, Tunc¸alp O, Oladapo OT, Adanu RM, et al. (2015) How women are treated during facility-based childbirth: Development and validation of measurement tools in four countries-phase 1 formative research study protocol. Reprod Health 12: 60.

- Adewemimo AW, Msuya SE, Olaniyan CT, Adegoke AA (2014) Utilisation of skilled birth attendance in Northern Nigeria: A cross-sectional survey. Midwifery 30: e7-e13.

- Abegunde D, Kabo IA, Sambisa W, Akomolafe T, Orobaton N, et al. (2014) Availability, utilization and quality of emergency obstetric care services in Bauchi State, Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 128: 251-255.

- Tukur I, Cheekhoon C, Tinsu T, Muhammed-Baba T, Ijaiya MA (2016) Why women are averse to facility delivery in northwest Nigeria: A qualitative inquiry. Iran J Public Health 45: 586-595.

- Doctor HV, Findley SE, Ager A, Cometto G, Afenyadu GY, et al. (2012) Using community-based research to shape the design and delivery of maternal health services in Northern Nigeria. Reprod Health Matters 20: 104-112.

- Fagbamigbe AF, Idemudia ES (2015) Barriers to antenatal care use in Nigeria: Evidences from non-users and implications for maternal health programming, BMC Preg Childbirth 15: 95.

- Fotso JC, Ezeh AC, Essendi H (2009) Maternal health in resource-poor urban settings: How does women’s autonomy in influences the utilization of obstetric care services? Reprod Health 6: 9.

- Crowe S, Utley M, Costello A, Pagel C (2012) How many births in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia will not be attended by a skilled birth attendant between 2011 and 2015? BMC Preg Childbirth 12: 4.

Citation: Shaguy JA (2019) How Social Constructs and Cultural Practices Erect Barriers to Facility Deliveries in Rural Nigeria: A Review of the Literature. J Preg Child Health 6:410.

Copyright: © 2019 Shaguy JA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 3234

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Nov 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2354

- PDF downloads: 880