Case Report Open Access

How do Medical Students Respond to the Concept of Compassion without Being Cued on its Importance? What is the Role of Compassion in Medicine, Medical Education and Training?

Janet Lynn Roseman*, Arif M. Rana

Nova Southeastern University, College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

Objective: The role of compassion is usually not well addressed in medical education. Several scenarios of breast cancer and the use of medical informatics were presented to the participants without referring to the progression of the disease as anything but stages without identifiable human beings possessing the ?disease?. The purpose of this study was to find out how medical students would respond to the omission of pertinent patient information that would create a holistic model of a ?person? including mind and body. Materials and Methods: Two presentations were given to 25 participants. All participants were second year medical students. The first half of the presentation was on the ?Role of Informatics in Detecting Breast Cancer? (Dr. Rana) while the second half of the presentation was on the topic of ?The Compassionate Physician? (Dr. Roseman). After the informatics section of the presentation, the participants were asked to fill out a brief survey with 9 questions. Participation in the questionnaire was anonymous. The questionnaire examined students? perceptions of whether the informatics portions of the presentation ignored cultural and compassionate aspects of the cases discussed, and asked participants to identify the importance of compassion in the medical encounter. Results: Out of the 25 participant?s responses, only 16% (n =4) indicated that there needed to be a more humanistic approach to the presentation. Few participants identified the importance of compassion in the patient/physician encounter; none of them were aware of the purposeful removal of any form of ?compassion? from the presentation or identified this omission as problematic. Discussion: Most medical students are so used to scientific presentations that support the deeply instilled philosophy in the medical culture that views patients as ?their disease?. Although, medical students indicate a keen awareness of the importance of ?compassion? for patients, they were not able to identify the lack of ?compassion?. Conclusion: Medical school training for the most part perpetuates the patient as ?diagnosis? and thus, medical students are often quite dismissive of the psycho-social aspects of serious illness because its relevancy is not acknowledged as important as clinical expertise. The results of this study emphasize the importance of integrating humanistic physician training into the medical school curriculum.

Keywords

Cancer, compassion, empathy, informatics, medical education, and patient care

Background

The topics of compassion and physician empathy are almost always considered “soft” topics and thus do not hold the same respect in medical education. What is especially troublesome is the fact that medical schools (both osteopathic and allopathic) are not only involved in the teaching of medicine to create the next generation of physicians, but that by its very nature, medicine is the interaction between human beings. For example, one of the core principles of osteopathic medicine is to “approach the patient with the recognition of the entire clinical context, including mind-body and psychosocial interrelationships” as well as the recognition to “treat each patient as a whole person, integrating mind, body and spirit” (American Academy of Osteopathic Medicine). As an expert in spirituality and medicine and compassionate care, it is worrisome to me that these topics are not given their due for I know from experience that the lack of compassion can have far-reaching psychological effects on both patient and the family. This lack of recognition of the importance of compassionate care especially when a serious medical diagnosis is in place is unconscionable and an ethical violation of the physician’s oath to “First Do No Harm.”

Osteopathic medicine has a long and distinguished tradition of training medical students in the mind, body, spiritual paradigm. Sir William Osler, a former professor at Oxford, and considered the “father” of osteopathic medicine is often cited for his belief that; “it is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has.” Osler’s “knowing the patient” philosophyrevolved around taking a good history, observing signs and symptoms, and asking the right questions (Gyles, 2009). While this approach continues to be the dominant approach today in medicine, it is limited because it may prevent authentic communication and connection between physician and patient especially if the physician is not comfortable with the humanistic aspects of medicine. This paper will present the results from a specially designed study created to identify and understand medical student’s awareness of the humanistic domain of patient care, particularly as it applied to oncology patients. In an effort to understand and identify this awareness, the paper will present some findings from the results from the study. My colleague, Dr. Rana was also interested in humanistic medical training so I shared with him the idea for exploring the consciousness of group dynamics in terms of “humanistic medicine” and wondered if medical students were presented with only a diagnosis and diagnostic scientific information, as well as a removal of information that would identify the patient as a real, living body, would anyone notice this omission?

Providing medical education that was “without heart” was not comfortable for the investigators of this study, however it was necessary in order to access the efficacy of this study. Purposely omitting any suggestion of integrative medicine protocols that could perhaps lessen the patient suffering, as well as omitting any cultural identification was also integrated in the presentation. The authors made every effort to spell out all omissions blatantly in an attempt to cue the medical students to help identify missing humanistic elements. We wanted to find out how medical students would respond to the topic of compassion in patient care when this topic was not encouraged, introduced or even mentioned in the classroom. According to a 2014 study by Anandarajah and Roseman, despite the apparent central role of compassion in medicine, review of the literature reveals remarkably few articles specifically addressing compassion. Most relate to nursing or behavioral health, with many addressing the concerning issue of compassion fatigue and burnout. The medical education literature does address the erosion of values and ideas during medical training and calls for curricula that specifically address fostering compassion (Anandarajah & Roseman, 2013).

Although, our study was small, a lack of compassion is more of the norm than the exception. Additionally, the authors felt that they offered the medical students several attempts to consciously think about the “patient” when they were filling out the survey. We realize that we are not necessarily training oncology physicians, however, the topic of compassionate medicine is not a topic that is confined to working in the field of oncology for it is a necessity for any human encounter. Another study by Pollak et al. found that oncologists encountered few empathic opportunities and responded with empathic statements infrequently. Empathic responses were more prevalent among younger oncologists and among those who were self-rated as “socio-emotional” thus creating an inherent dismissive quality using this label. The study continues to suggest that; “to reduce patient anxiety and increase patient satisfaction and adherence, oncologists may need training to encourage patients to express emotions and to respond with empathy to patients’ emotions” (Pollak, Kathryn, & Robert et al., 2007). The fact that this particular study only suggests that physicians “may” need training to “respond empathetically” to their patients is very problematic and ignores the fact that they are in a position to help another human being who brings with them all aspects of their being---mind, body and soul in the encounter.

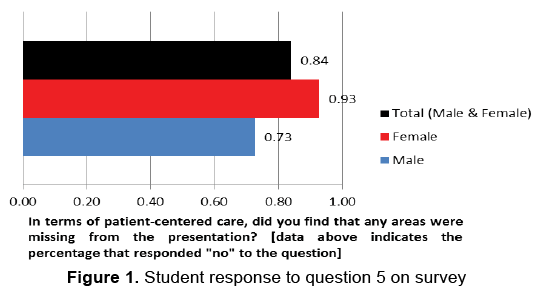

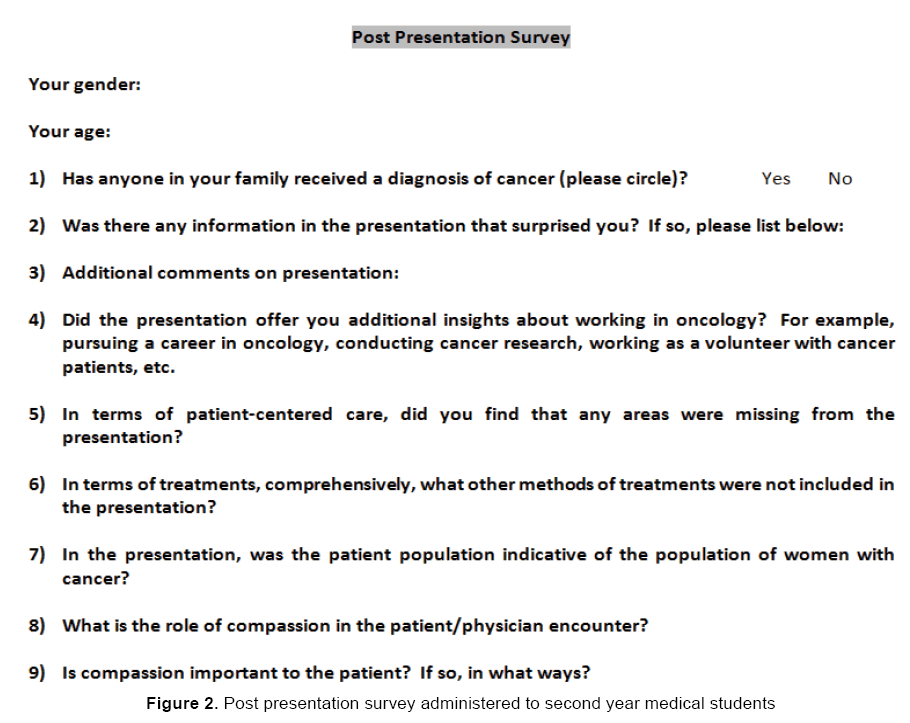

When we isolate just one of the questions on the survey, (the heart of the research study): “In terms of patient centered care, did you find any areas that were missing” from the presentation given on breast cancer, 84% (n =21) of the survey participants, i.e. only 4 medical students identified that something was lacking including topics such as: “family relations”, “more diagnosis than patient based”, “mental toll”, “more story needed” and there was no difference between the number of female/male responses (Figure 1). Even more surprising is that when we look at question 8 of the survey (Figure 2), “What is the role of compassion in the patient/physician encounter?” out of the 22 responses—the themes of importance of compassion are identified as important, and one student wrote: “Compassion is the gateway to the patient’s soul.” Yet somehow there seems to be a disconnection from the idea of compassion in the medical encounter and the actual delivery of compassionate medicine. The delivery of compassionate medicine can only occur when there is a consciousness that this is not only important, but it is necessary not only to the practice of medicine, but to the practice of “being human”.

Materials and Methods

A cohort of second year medical students was shown an hour long presentation explaining the diagnostic stages of breast cancer for a Caucasian patient. Graphic slides offered pictorial evidence of the disease while a lecture on the use of medical informatics as a tool for physician’s diagnosis and treatments was offered. After the informatics section of the presentation, 25 second year medical students were asked to fill out a brief survey with 9 questions that addressed various aspects of their understanding of the presentation from a “patient centered” and humanistic approach. The survey explored medical student’s personal experiences with cancer, interest in oncology as a career choice, knowledge about integrative medicine protocols/interventions, cultural diversity and the role of compassion in oncology patient care. Participation in the questionnaire was anonymous. The questionnaire was examined to discover students’ perceptions of whether the informatics portions of the presentation ignored cultural and compassionate aspects of the cases discussed. After this, a lecture on “The Compassionate Physician” was presented.

Discussion

The diagnosis of cancer or any serious life threatening disease is devastating. It wreaks havoc not only psychologically on the patient, but as a former caregiver to both parents who had a cancer diagnosis; it is a challenging and tragic situation for close family members, especially when they deal with physicians who have no interest in discussing patient care from a humanistic perspective.

What is most concerning is that the medical school training for the most part perpetuates the patient as “diagnosis” and thus, medical students are not often encouraged to discuss the psycho-social aspects of serious illness and the psychological or spiritual impact of illness because its relevancy is not acknowledged. The idea that there isn’t time in the curricula to train medical students in empathy and caring is a ridiculous argument, how can there not be time to integrate whole care of human beings into the training? Medicine and the training associated with it is a healing art, not a factory training program. Teaching all the aspects of clinical care and including the psychosocial- spiritual implications of each “diagnosis” can help physicians to “see” their patients as whole human beings. Presentation of the “whole person” from year one of the medical school curriculum is prudent to foster humanistic medical training.

Results

Identified results were overwhelming from the 25 participants in a variety of areas including the overall consensus that “nothing” was missing from presentation and only 16% indicated that there needed to be a more humanistic approach to the presentation. Their comments included the omission of the "mental toll of the diagnosis”, and the belief that the presentation was only “diagnostically based.” Another student indicated that there was a lack of inclusion of both patient and family members as well. Most agreed that the patient presented (Caucasian) was indicative of the national patient population with breast cancer, without regard for other races and ethnicity affected by this diagnosis. Overwhelmingly, the participants concluded that chemotherapy and radiation were the only treatment plans discussed, however, not one of the participants identified any type of integrative/complementary treatment plan missing from the medical protocols presented during the role of technology in breast cancer lecture. Finally, although, few participants identified the importance of compassion in the patient/physician encounter, none of them were aware of the purposeful removal of any form of “compassion” from the presentation or identified this omission as problematic.

Conclusion

We believe that most medical students are so used to scientific presentations that support the deeply instilled philosophy that views patients as “their disease,” that they did not identify any “missing elements” from the technological portion of the lecture. Although, medical students indicate a keen awareness of the importance of “compassion” for patients, they were not able to identify the lack of “compassion”. Results of the questionnaire from the medical students indicated a lack of identifiable cultural statistics and the purposeful lack of discussion of any integrative/complementary medicine treatments. We find this to be problematic particularly because it is not unique to the prominent model of medicine. However, we were pleased to read the humanistic themes identified by most participants relating to the importance of compassion. It’s odd that the medical students could identify as an important factor in the practice of medicine, but could not recognize its importance enough to identify it when needed.

Limitations of the Study

It is important to highlight that the study only examined the perceptions of second year medical students on the role of compassion in medical care after they viewed a lecture on the technological aspects of breast cancer, and it was a small sample of participants. The study did not include other medical students in different years of training or include participants from other health care professions. We hope to continue the research to include a greater number of participants in the future as well as participants from other areas of the healthcare professions.

About the Authors

Dr. Janet Lynn Roseman is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medical Education at Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She is an expert in Spirituality and Medicine and Compassionate Care and is the Director of the Sidney Project in Spirituality and Medicine and Compassionate Care™ and the author of If Joan of Arc Had Cancer: Finding Courage, Faith and Healing from History’s Most Inspirational Woman Warrior (New World Library).

Dr. Arif M. Rana is an Assistant Professor of Biomedical Informatics and Medical Education and Director of Faculty Development at Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He is well versed in curriculum development and instructional design and has substantial knowledge of programming languages. His research interests are in medical education, healthcare databases, and data mining.

References

- Anandarajah, G., &Roseman,J.L.A. (2013).A qualitative study of physicians' views on compassionate patient care and spirituality: medicine as a spiritual practice?Rhode Island Medical Journal, 97, 17-22.

- Aomatsu, M., Otani, T., Tanak, A., et al. (2013).Medical Students' and residents' conceptual structure of empathy: a qualitative study. Educational Health (Abingdon), 26(1), 4-8.

- Core values according to the American Academy of Osteopathic Medicine.

- Gyles, C. (2009). On the cusp of a paradigm shift in medicine?The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 50(12), 1221-1222.

- Pollak, K.I., Robert, M.A., Amy, S.J., Stewart, C.A., Maren, K.O., Amy,P.A., et al. (2007).Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer.Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(36), 5748-5752.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14538

- [From(publication date):

March-2015 - Apr 06, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9924

- PDF downloads : 4614