Holistic Study of Whole Genomes

Received: 09-Dec-2017 / Accepted Date: 11-Dec-2017 / Published Date: 14-Dec-2017

Abstract

Two complementary goals of biological research are to understand how each organism works and how that relates to other organisms. Specifically, the function of all genes and non-genes (i.e., all the regions of a genome that do not code for any genes) of each organism and how its genes and non-genes compare with those of other organisms. The progress in DNA sequencing has generated large amounts of sequence data, and many computer programs have been developed to interpret these data, especially in identifying and analyzing the similarities among genes and genomes. Unfortunately, in the zeal of finding similarities, the differences among genes and genomes are often not just simply ignored, but intentionally masked, trimmed, or filtered. With the increase in the number of genes or organisms being compared, the deleted data increase exponentially.

Keywords: Genome; DNA sequencing; Mutations; Processing; Organism

Editorial

Two complementary goals of biological research are to understand how each organism works and how that relates to other organisms. Specifically, the function of all genes and non-genes (i.e., all the regions of a genome that do not code for any genes) of each organism and how its genes and non-genes compare with those of other organisms.

The progress in DNA sequencing has generated large amounts of sequence data, and many computer programs have been developed to interpret these data, especially in identifying and analyzing the similarities among genes and genomes. Unfortunately, in the zeal of finding similarities, the differences among genes and genomes are often not just simply ignored, but intentionally masked, trimmed, or filtered. With the increase of genes or organisms compared, the cropped data increase exponentially.

The tragic consequence is that the very data we need to answer a question such as “what makes a dog a dog, instead of a cat” are cut out, because much of our hard-generated data have been rendered invisible.

The solution?

A holistic approach

Use all the data, all the sequence of whole genes, all the genes of whole genomes. Instead of cherry-picking only those regions of genomes that are similar enough to be aligned, carefully inspect each section.

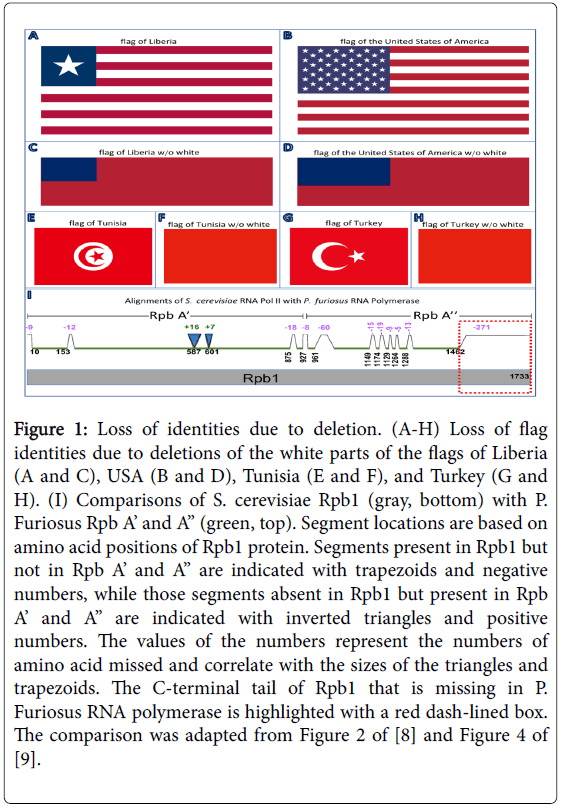

The reason is simple; all segments of the genome of an organism are important for the making and functioning of that organism. Any clipping, however benign it appears, may be devastating. To illustrate the point, I took the flags of Liberia and the United States (Figure 1A and 1B) and deleted the white parts of the flags. This resulted in two flags that look nearly identical (Figure 1C and 1D). Furthermore, neither citizens of Liberia nor of United States would regard either flag as their national flag. The consequence of deleting the white parts from the flags of Tunisia and Turkey was even worse; it generated two identical flags (Figure 1E and 1H) that neither country would accept as their national banner.

The removal of the flag parts is not just any analogy without biological significance. Panel I of Figure 1 is a schematic drawing of the comparison of the largest subunit of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase II, Rpb1, and the two subunits of the RNA polymerase of the archaea Pyrococcus furiosus, Rpb A’ and Rpb A”. Rpb1 has a C-terminal tail that is missing in the archaeal RNA polymerase. Such fragment is normally referred to as a eukaryoticspecific extension. This C-terminal accounts for less than 16% of Rpb1, and Rpb1 is merely one of the 6091 proteins encoded in the yeast genome [1]. Removal of this C-terminal will not change a yeast cell into a simpler cell, it will actually kill the cell. Thus, this C-terminal is indispensable for the existence of yeast. Many studies have shown that this C-terminal is critical for yeast transcription initiation, elongation, termination, and RNA processing [2-7].

Figure 1: Loss of identities due to deletion. (A-H) Loss of flag identities due to deletions of the white parts of the flags of Liberia (A and C), USA (B and D), Tunisia (E and F), and Turkey (G and H). (I) Comparisons of S. cerevisiae Rpb1 (gray, bottom) with P. Furiosus Rpb A’ and A” (green, top). Segment locations are based on amino acid positions of Rpb1 protein. Segments present in Rpb1 but not in Rpb A’ and A” are indicated with trapezoids and negative numbers, while those segments absent in Rpb1 but present in Rpb A’ and A” are indicated with inverted triangles and positive numbers. The values of the numbers represent the numbers of amino acid missed and correlate with the sizes of the triangles and trapezoids. The C-terminal tail of Rpb1 that is missing in P. Furiosus RNA polymerase is highlighted with a red dash-lined box. The comparison was adapted from Figure 2 of [8] and Figure 4 of [9].

Since the very life of an organism may hinge on a small part of its genome, even a single base pair as shown by the identification of many lethal point-mutations, how could we omit a section of a genomes simply because it does not look like any regions of other genomes?

It is foreseeable that a tremendous amount of knowledge can be gained by comparing and contrasting different life forms using both similar and different sequences of genes and genomes. To start with, we will need to develop means to visualize the whole data, including the similarities and dissimilarities, as well as patterns of the differences. Do not just list genes with homologs but also those without homologs. Do not just compare genes but also non-genes. In short, use the whole data to study the whole organisms.

References

- Lin D, Yin X, Wang X, Zhou P, Gu F (2013) Re-annotation of protein-coding genes in the genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae based on support vector machines. PLoS One 8: e64477.

- Egloff S, Dienstbier M, Murphy S (2012) Updating the RNA polymerase CTD code: adding gene-specific layers. Trends Genet 28: 333-341.

- Heidemann M, Hintermair C, Voß K, Eick D (2013) Dynamic phosphorylation patterns of RNA polymerase II CTD during transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta 1829: 55-62.

- Hsin JP, Manley JL (2012) The RNA polymerase II CTD coordinates transcription and RNA processing. Genes Dev 26: 2119-37.

- Napolitano G, Lania L, Majello B (2014) RNA polymerase II CTD modifications: how many tales from a single tail. J Cell Physiol 229: 538-544.

- Srivastava R, Ahn SH (2015) Modifications of RNA polymerase II CTD: Connections to the histone code and cellular function. Biotechnol Adv 33: 856-872.

- Phatnani HP, Greenleaf AL (2006) Phosphorylation and functions of the RNA polymerase II CTD. Genes Dev 20: 2922-2936.

- Kusser AG, Bertero MG, Naji S, Becker T, Thomm M, et al. (2008) Structure of an archaeal RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 376: 303-307.

- Tan C, Tomkins JP (2015) Information Processing Differences Between Archaea and Eukarya—Implications for Homologs and the Myth of Eukaryogenesis. Answers Research Journal 8: 121–141.

Citation: Tan CL (2017) Holistic Study of Whole Genomes. J Genome 1: e102.

Copyright: ©2017 Tan CL. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 5434

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Mar 28, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4423

- PDF downloads: 1011